Abstract

Individuals with high-functioning autism sometimes exhibit intact or superior performance on visuospatial tasks, in contrast to impaired functioning in other domains such as language comprehension, executive tasks, and social functions. The goal of the current study was to investigate the neural bases of preserved visuospatial processing in high-functioning autism from the perspective of the cortical underconnectivity theory. We used a combination of behavioral, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), functional connectivity, and corpus callosum morphometric methodological tools. Thirteen participants with high-functioning autism and thirteen controls (age-, IQ-, and gender-matched) were scanned while performing an Embedded Figures Task (EFT). Despite the ability of the autism group to attain behavioral performance comparable to the control group, the brain imaging results revealed several group differences consistent with the cortical underconnectivity account of autism. First, relative to controls, the autism group showed less activation in left dorsolateral prefrontal and inferior parietal areas and more activation in visuospatial (bilateral superior parietal extending to inferior parietal and right occipital) areas. Second, the autism group demonstrated lower functional connectivity between higher-order working memory/executive areas and visuospatial regions (between frontal and parietal-occipital). Third, the size of the corpus callosum (an index of anatomical connectivity) was positively correlated with frontal-posterior (parietal and occipital) functional connectivity in the autism group. Thus, even in the visuospatial domain, where preserved performance among people with autism is observed, the neuroimaging signatures of cortical underconnectivity persist.

Keywords: Embedded figures task, Functional connectivity, Corpus callosum, functional MRI

One of the enigmatic aspects of autism is that people with the disorder exhibit preserved or even enhanced performance on visuospatial tasks (Baron-Cohen & Hammer, 1997; Brian & Bryson, 1996; De Jonge et al., 2006; Jolliffe & Baron-Cohen, 1997; Lee et al., 2007; Manjaly et al., 2007; Mottron et al., 1999; 2003; 2006; Ring et al., 1999; Shah & Frith, 1983). For example, Shah and Frith (1983) demonstrated that children with high-functioning autism exhibited superior performance relative to IQ- and age-matched controls on the Embedded Figures Task (EFT), in which individuals are asked to locate a simple figure that is embedded in a more complex configuration.

A recently proposed theoretical account of autism, the cortical underconnectivity theory (Just et al., 2004; 2007), provides a neurobiological explanation of the psychological processes underlying the disorder. This theory posits that autism is a neural systems disorder marked by inefficient interregional brain connectivity between frontal and posterior areas resulting in a deficit in integration of information at both psychological and neural levels. The theory predicts that if a task does not require tight integration between frontal and more posterior regions, performance is not likely to be disrupted in autism. In particular, performance of a task like the EFT in autism should not suffer from a lack of integration of the information about the complex figure. However, underconnectivity theory predicts that despite the preserved behavioral performance on the EFT in autism, the underlying brain activation should exhibit the signature of autism.

The underconnectivity account is based on findings of both functional underconnectivity (a lower than normal degree of synchronization of fMRI-measured brain activation between pairs of brain regions) and associated structural connectivity differences (measured as white matter differences) in individuals with autism, and has been supported by a growing number of neuroimaging studies across different domains (Just et al., 2004, 2007; Kana et al., 2006, 2007; Keller et al., 2007; Koshino et al., 2005, 2008; Mason et al., 2008). Morphometric studies of white matter have found aberrations in the volumes of various white matter regions in autism. In particular, the findings of a reduction in corpus callosum size suggest that there may be an impairment in anatomical connectivity between various cortical regions (Hardan, Minshew, & Keshavan, 2000; Just et al., 2007; Manes et al., 1999; Piven et al., 1997; Quigley et al., 2001; Vidal et al., 2006). We do not propose to discern a direction of the causality of anatomical and functional underconnectivity, but to document their co-occurrence in a dynamic system.

Previous neuroimaging studies of the EFT in autism have demonstrated reduced frontal activation and greater posterior activation in autism relative to controls (Lee et al., 2007; Manjaly et al., 2007; Ring et al., 1999) and have implicated the use of different strategies by the two groups (Ring et al., 1999). The EFT requires participants to mentally decompose the complex figure into its structural components and to decide whether some component matches the target figure (Manjaly et al., 2007). It is possible that processing an entire complex figure may require participation of frontal regions that may not be necessary or useful for performing the EFT, whereas processing the simpler components of the figure may rely more on occipital and parietal areas. On the basis of the underconnectivity theory, we hypothesized that poorer access to frontal regions (or poorer frontal-posterior coordination) would not handicap people with autism in the EFT.

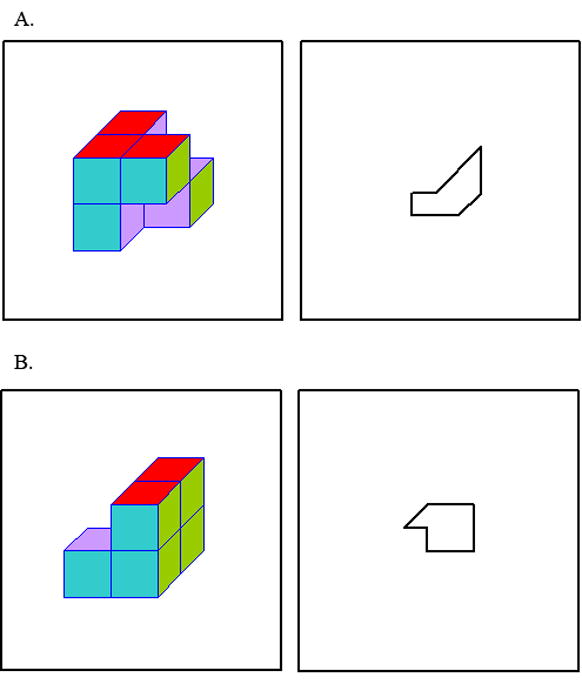

One enhancement our study attempted to provide over previous studies was the development of a more systematic and homogenous set of the EFT stimuli containing a global 3D embedding object and a 2D contour as the target (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Examples of the EFT stimuli used in the current study. Answer to (A): Purple and green surfaces at the back lower right. Answer to (B): A catch-trial.

Method

Participants

Thirteen high-functioning individuals with autism and 13 control participants matched on age-, IQ-, and socioeconomic status (Hollingshead, 1957) were included in the study (group demographic data are shown in Table 1). The diagnosis of autism was established using the ADI-R (Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised, Lord et al., 1994) and the ADOS-G (Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic, Lord et al., 2000), supplemented with expert clinical opinion, according to accepted criteria of high-functioning autism (Minshew, 1996). Handedness was determined with the Lateral Dominance Examination from the Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery (Reitan, 1985), revealing that one participant with autism and one control participant were left-handed. The mean of total brain volume in cm3 (GM+WM) did not differ reliably between the two groups (Autism: M = 1124.97, SE = 30; Controls M = 1111.65, SE =19; t (24) = .37, n.s.). (Additional exclusionary criteria are identical to those reported in Just et al., 2007; Kana et al., 2006; Mason et al., 2008; Koshino et al., 2008.)1

Table 1.

Demographic data for participants.

| Autism | Control | t (24) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Range; Mean ± SD | 15.3-35.4; 19 ± 5.5 | 16.7-29.9; 22.1 ± 4.25 | 1.96 | .12, n.s. |

| VIQ | Range; Mean ± SD | 89-119; 107.7 ± 9.03 | 96-120; 109.8 ± 6.75 | 1.16 | .51, n.s. |

| PIQ | Range; Mean ± SD | 100-121; 109.5 ± 11.4 | 100-119; 110.5 ± 5.96 | .87 | .78, n.s. |

| FSIQ | Range; Mean ± SD | 95-123; 109.5 ± 8.7 | 101-119; 111.5 ± 5.75 | 1.18 | .49, n.s. |

| SES | Range; Mean ± SD | 1-6; 2.85 ± 1.06 | 2-6; 3 ± 1.04 | .39 | .72, n.s. |

| Handedness | Right : Left | 12 : 1 | 12 : 1 | ||

| Gender | Male : female | 11 : 2 | 13 : 0 | ||

| Race | White : Other | 13 : 0 | 12 : 1 |

Experimental paradigm

Participants decided if the target figure was embedded in the simultaneously presented more complex figure and indicated their decision, pressing one of two response buttons. Twelve test items, each displayed for 12 sec, were presented (six blocks of two test items per block). In four of the 12 trials, the target figure was not a part of the more complex figure. A 12-second or 24-second fixation condition was presented between blocks.

fMRI procedure and analyses

Imaging was conducted on a 3-Tesla Siemens Allegra scanner. For the functional imaging, a gradient echo, echo-planar pulse sequence was used to acquire 17, 5-mm thick slices with a 1-mm gap with TR = 1000 ms, TE = 30 ms, flip angle = 60°, and in-plane resolution 3.125 × 3.125 mm. A structural 160-slice 3D MPRAGE volume scan with TR = 200 ms, TE = 3.34 ms, flip angle = 7°, FOV = 25.6 cm, 256 × 256 matrix size, and 1 mm slice thickness was also acquired.

Distribution of activation

The data were analyzed using SPM2 (Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, London, UK). Images were corrected for slice acquisition timing, motion-corrected, normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template, resampled to 2 × 2 × 2 mm voxels, and smoothed with an 8-mm Gaussian kernel. Group analyses were performed using random-effects models in which contrast images of parameters for the EFT condition minus the fixation baseline were entered as the dependent measure. An uncorrected height threshold of p < .005 and an extent threshold of ten voxels were used.

Functional connectivity

Functional connectivity was computed as a correlation between the average time courses of all the activated voxels in each member of a pair of regions of interest (ROIs). Twelve ROIs were defined to encompass the main clusters of activation in the activation map for each group in the EFT-Fixation contrast, using previously described procedures (Just et al., 2007; Kana et al., 2006; Mason et al., 2008). The time course of the activation was extracted for each ROI for each participant from voxels that showed a significant difference between the EFT and Fixation conditions (p < .05, corrected for multiple comparisons) in the individual participant’s GLM.

The correlation between the time courses of two ROIs was computed only on images from the experimental condition (excluding the Fixation condition), so that it reflects the synchronization of activation in two areas while the participant is performing the task. Fisher’s r to z′ transformation was applied to the correlation coefficients, to be used in further analyses. The ROI pairs were aggregated into two categories: frontal-posterior ROIs (frontal-parietal and frontal-occipital pairs) and all other pairs (pairs of ROIs within frontal, parietal, and occipital lobes and between parietal-occipital pairs). The functional connectivities of these two categories were submitted to a 2 (Group) by 2 (Connection type) mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Corpus callosum morphometry

The cross-sectional area of the midsagittal slice of the corpus callosum was measured as in previous studies (Just et al., 2007; Kana et al., 2006; Mason et al., 2008) and normalized relative to total brain volume.

Results

Overview

Despite the similarity of the behavioral performance of the two groups, the autism group showed more activation than controls in visuospatial areas and less activation in left frontal areas, and had reliably lower functional connectivity between frontal regions and posterior regions. Frontal-posterior functional connectivity was correlated with corpus callosum size in the group with autism.

Behavioral results

There were no reliable behavioral differences between the groups in either response times (control: M = 5816 ms, SE = 231.7; autism: M = 5847 ms, SE = 421.5; t(24) = 0.73, n.s) or error rates (control: M = 15.4%, SE = 4.3; autism M = 24%, SE = 6; t(24) = 1.61, n.s.). These results are consistent with the behavioral findings in other neuroimaging studies on embedded figures tasks (Lee et al., 2007; Manjaly et al., 2007; Ring et al., 1999). In addition, the rate of false alarms on catch trials did not differ significantly between the groups (control: M = 18.3%; autism: M = 25 %, t(24) = 0.60, p > .5) suggesting no differential bias across groups to identify complex figures as containing an embedded figure.

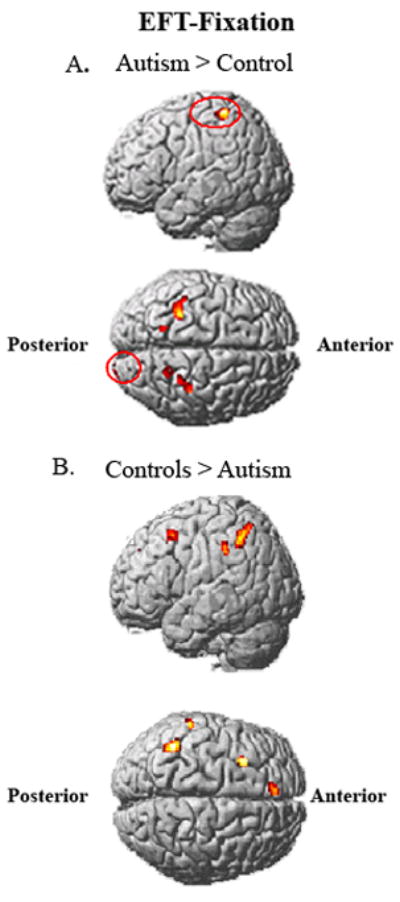

Group differences in brain activation

The autism group had reliably less activation than controls in left frontal (left DLPFC, left superior medial frontal gyrus) and left inferior parietal areas. The autism group had higher activation in bilateral superior parietal and right occipital areas (Figure 2 and Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

Between-group contrasts of activation for EFT-Fixation. Group difference showing areas where the autism group had more activation than controls (A); Group difference showing areas where the participants with autism had less activation than the control group (B).

Table 2.

Activation differences between groups for the EFT-Fixation contrast.

| Location of peak activation | Cluster Size | t(24) | MNI Coordinates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||

| Areas in which autism participants showed more activation than control participants | |||||

| L postcentral, superior parietal and inferior parietal | 215 | 3.88 | -44 | -38 | 64 |

| R superior parietal, precuneus and inferior parietal | 93 | 3.68 | 20 | -50 | 54 |

| R postcentral, superior parietal and inferior parietal | 136 | 3.56 | 28 | -40 | 56 |

| L superior parietal, precuneus and inferior parietal | 38 | 3.32 | -18 | -56 | 58 |

| R superior occipital, middle occipital and cuneus | 17 | 3.25 | 26 | -100 | 12 |

| MNI Coordinates | |||||

| Location of peak activation | Cluster Size | t(24) | x | y | z |

| Areas in which autism participants showed less activation than control participants | |||||

| L superior frontal and superior medial frontal | 61 | 3.98 | -8 | 42 | 38 |

| L middle frontal and precentral | 95 | 3.83 | -30 | 14 | 46 |

| L thalamus and putamen | 91 | 3.83 | -20 | -12 | 2 |

| L supramarginal and inferior parietal | 48 | 3.76 | -62 | -34 | 40 |

| L inferior parietal and angular | 167 | 3.69 | -42 | -48 | 46 |

Note: The threshold for activation was p < .005 with a spatial extent of 10 voxels, uncorrected for multiple comparisons. Region labels apply to the entire cluster. MNI coordinates and t-values are given for the peak activated voxel in each cluster.

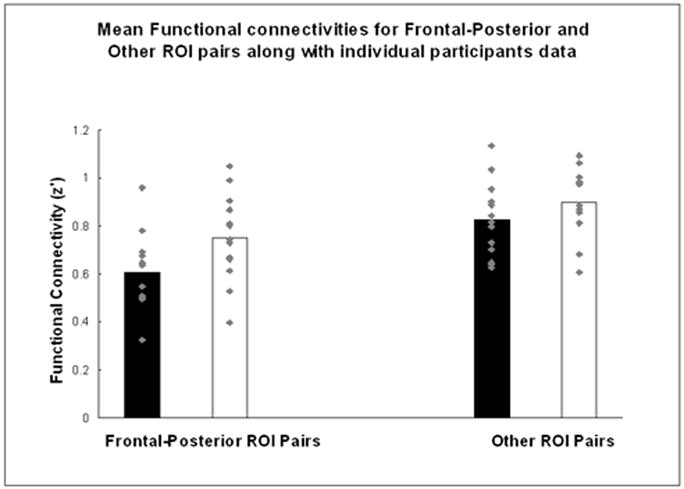

Functional connectivity

A 2 (Group) by 2 (Connection Type: frontal-posterior vs. other) mixed ANOVA indicated a main effect of reliably lower functional connectivities in the autism group than the control group (autism: M = 0.61, SE = 0.04; control: M = 0.75, SE = 0.04; F(1, 24) = 5.33, p < .05). In addition, there was a main effect of connection type, such that frontal-posterior functional connectivities (Fisher’s transformed r’s) were lower than other inter-regional connectivities (frontal-posterior: M = 0.91, SE = 0.03; other: M = 1.00, SE = 0.03; F(1, 24) = 85.14, p < .0001). Of primary interest, however, is the reliable Group by Connection Type interaction [F(1, 24) = 7.20, p < .05], with the autism group showing reliably lower functional connectivity than controls for frontal-posterior connectivities [t(24) = 2.61, p < .05], but not for other connectivities [t(24) = 1.91, n.s.], confirming the prediction of lower frontal-posterior functional connectivity in autism (see Figure 3).2

FIGURE 3.

Functional connectivity interaction between group (participants with autism and control participants) and connection type (Frontal-Posterior ROI pairs versus Other pairs of ROIs), along with individual participants’ functional connectivity data.

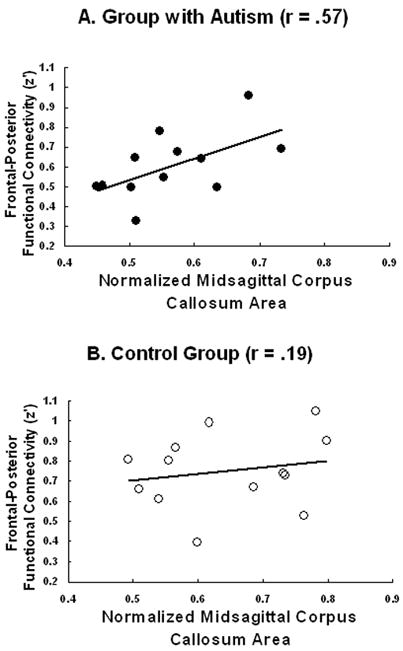

Relationship between corpus callosum size and functional connectivity

Consistent with previous studies, the corpus callosum was smaller in the group with autism than in controls (Hardan, Minshew, & Keshavan, 2000; Just et al., 2007; Manes et al., 1999; Mason et al., 2008; Piven et al., 1997; Quigley et al., 2001; Vidal et al., 2006). A regression analysis using normalized corpus callosum size to predict functional connectivity between frontal and posterior areas revealed a reliable positive correlation between the two measures within the group with autism but not in the control group [autism (r = .57, t(10) = 2.20, one-tailed p < .05; control: r = .19, t(11) = 0.66, n.s.), as shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Correlation between the midsagittal area of the corpus callosum and the mean functional connectivity between frontal-posterior areas for autism (A) and controls (B).

Discussion

The central contribution of this study is the demonstration of frontal-posterior functional underconnectivity in autism during performance of an embedded figures task, a task in which participants with autism showed preserved performance. Previous reports of functional underconnectivity have investigated higher-level tasks (like language comprehension, working memory, problem solving, and Theory of Mind) on which people with autism have demonstrated impaired performance. This is one of the first studies reporting underconnectivity in a task in which people with autism are assumed to have no disadvantage, and one of the first focusing on visuo-spatial processing. Other findings include reduced frontal recruitment and increased activation of posterior areas, and a positive relationship between corpus callosum size and frontal-posterior functional connectivity, in the autism group.

Participants with autism demonstrated more activation in brain areas typically involved in visuospatial processing (bilateral superior parietal and right occipital), while the control participants exhibited more left-lateralized activation in executive and working memory regions (DLPFC/superior medial). Other studies on the EFT have also shown more right-lateralized occipital activation in the autism group (Ring et al., 1999; Manjaly et al., 2007) and activation in left posterior parietal and frontal areas in controls (Manjaly et al., 2007). More right hemispheric activation in occipital and superior parietal areas in the autism group may indicate greater reliance on visuo-spatial processing, and decreased prefrontal activation may indicate a reduced reliance on executive processes, thus indicating differences in cognitive strategies used by the groups.

This decreased reliance on frontal processes and an increased reliance on occipital and superior parietal regions in autism are consistent with underconnectivity between frontal and posterior regions. One possible explanation of why frontal-posterior underconnectivity in autism might lead to preserved (or sometimes enhanced) performance on the EFT is that on lower-level perceptual tasks, the integration of higher-order executive/working memory regions with visuospatial regions might not be beneficial. Relying more on visuospatial regions on a perceptual task can result in intact (if not enhanced) performance.

Finally, the study demonstrated a relation between frontal-posterior (functional connectivity and the mean segment size of the corpus callosum. A recent meta-analysis of corpus callosum studies indicated that reduced total corpus callosum size in autism was reported in seven out of ten studies, and the null findings in the remaining three were either due to power issues or sampling errors (Frazier & Hardan, 2009). The correlation between the functional and structural properties of brain tissues demonstrates how the behavioral characteristics of autism could emerge from biological substrates. In particular, even though the causality between the two cannot be discerned, the findings suggest the white matter in autism could constrain the communication among cortical areas. In the control group, the data indicated no correlation between the two measures, suggesting that their white matter applies no such constraint.

Although this study revealed new properties of preserved visuospatial performance in autism, it has certain limitations. First, like previous studies on the neural underpinnings of the EFT (Lee at al., 2007; Manjaly et al., 2007), the response measure did not ensure that the participants knew precisely where the target figure was located in the embedding figure. Future studies of the EFT should take this factor into account when comparing behavioral differences between the groups. A second limitation is the restricted size of the stimulus set. Finally, all previous studies on the EFT have used cross-sectional data. Hence, a longitudinal study investigating the neural correlates of the emergence of visuospatial skills in autism would contribute significantly to the literature.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Autism Centers of Excellence Grant HD055748 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and by a Pre-doctoral Training Grant from the Autism Speaks Foundation. The authors would like to thank Sarah Schipul and Stacey Becker for assistance with the data collection, and Yanni Liu for her helpful comments on the manuscript. We would also like to express our appreciation to the individuals and families who gave generously of their time and courage to participate in these imaging studies.

Footnotes

Six of the autism participants were taking medication (four were taking selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors and two were taking allergy medications). The data of all these individuals were qualitatively similar to the presented data of the autism participants without medication. Three of the control participants were taking allergy, asthma, or anti-acne medications. Their data were also similar to those of the other controls. One autism and four control participants were included in a Theory of Mind task (Kana et al., 2009); four autism and two control participants in a narrative comprehension task (Mason et al., 2008); one participant with autism in a spatial working memory task (Koshino et al., 2008); two participants with autism in the Tower of London task (Just et al., 2007); three autism and three control participants in an inhibition task (Kana et al., 2007); and four autism and two control participants in a visual sentence comprehension task (Kana et al., 2006).

To determine whether autism differentially affected inter-hemispheric versus intra-hemispheric frontal-posterior functional connectivity, an initial 2 (group) by 2 (connection type) mixed ANOVA was conducted, with connections categorized as inter-hemispheric or intra-hemispheric. This analysis found no reliable group by connection interaction [F(1,23) = .78, n.s.], indicating that autism similarly affects inter- and intra-hemispheric connectivities in this task. For this reason, both types of connectivity are included here in our measure of frontal-posterior connectivity, and this composite measure is related to corpus callosum size (which provides an index of white matter abnormality rather than a specific measure of inter-hemispheric anatomical connectivity) in further analyses.

References

- Baron-Cohen S, Hammer J. Parents of Children with Asperger Syndrome: What is the Cognitive Phenotype? Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1997;9(4):548–554. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1997.9.4.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brian JA, Bryson SE. Disembedding performance and recognition memory in autism/PDD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1996;37(7):865–872. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jonge MV, Kemner C, van Engeland H. Superior disembedding performance of high-functioning individuals with autism spectrum disorders and their parents: The need for subtle measures. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2006;36(5):677–683. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier TW, Hardan AY. A meta-Analysis of the corpus callosum in autism. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;66:935–941. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardan AY, Minshew NJ, Keshavan MS. Corpus callosum size in autism. Neurology. 2000;55(7):1033–1036. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.7.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AA. Four-factor index of social status. Yale University; New Haven, CT: 1957. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe T, Baron-Cohen S. Are people with autism and Asperger syndrome faster than normal on the Embedded Figures Test? Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 1997;38(5):527–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just MA, Cherkassky VL, Keller TA, Minshew NJ. Cortical activation and synchronization during sentence comprehension in high-functioning autism: Evidence of underconnectivity. Brain. 2004;127(8):1811–1821. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just MA, Cherkassky VL, Keller TA, Kana RK, Minshew NJ. Functional and anatomical cortical underconnectivity in autism: Evidence from an fMRI study of an executive function task and corpus callosum morphometry. Cerebral Cortex. 2007;17(4):951–961. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kana RK, Keller TA, Cherkassky VL, Minshew NJ, Just MA. Sentence comprehension in autism: Thinking in pictures with decreased functional connectivity. Brain. 2006;129(9):2484–2493. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kana RK, Keller TA, Minshew NJ, Just MA. Inhibitory control in high functioning autism: Decreased activation and underconnectivity in inhibition networks. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62(3):198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kana RK, Keller TA, Cherkassky VL, Minshew NJ, Just MA. Atypical frontal-posterior synchronization of Theory of Mind regions in autism during mental state attribution. Social Neuroscience. 2009;4(2):135–52. doi: 10.1080/17470910802198510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller TA, Kana RK, Just MA. A developmental study of the structural integrity of white matter in autism. NeuroReport. 2007;18(1):23–27. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000239965.21685.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshino H, Carpenter PA, Minshew NJ, Cherkassky VL, Keller TA, Just MA. Functional connectivity in an fMRI working memory task in high-functioning autism. NeuroImage. 2005;24(3):810–821. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshino H, Kana RK, Keller TA, Cherkassky VL, Minshew NJ, Just MA. fMRI investigation of working memory for faces in autism: Visual coding and underconnectivity with frontal areas. Cerebral Cortex. 2008;18(2):389–300. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PS, Foss-Feig J, Henderson JG, Kenworthy LE, Gilotty L, Gaillard WD, et al. Atypical neural substrates of Embedded Figures Task performance in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. NeuroImage. 2007;38(1):184–193. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH, Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, et al. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30(3):205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1994;24(5):659–685. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manes F, Piven J, Vrancic D, Nanclares V, Plebst C, Starkstein SE. An MRI study of the corpus callosum and cerebellum in mentally retarded autistic individuals. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 1999;11(4):470–474. doi: 10.1176/jnp.11.4.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manjaly ZM, Bruning N, Neufang S, Stephan KE, Brieber S, Marshall JC, et al. Neurophysiological correlates of relatively enhanced local visual search in autistic adolescents. NeuroImage. 2007;35(1):283–291. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manjaly ZM, Marshall JC, Stephan KE, Gurd JM, Zilles K, Fink GR. In search of the hidden: an fMRI study with implications for the study of patients with autism and with acquired brain injury. NeuroImage. 2003;19(3):674–683. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason RA, Williams DL, Kana RK, Minshew NJ, Just MA. Theory of mind disruption and recruitment of the right hemisphere during narrative comprehension in autism. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46(1):269–280. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minshew NJ. Autism. In: Berg BO, editor. Principles of child neurology. New York, USA: McGraw-Hill; 1996. pp. 1713–1729. [Google Scholar]

- Mottron L, Belleville S, Ménard E. Local bias in autistic subjects as evidenced by graphic tasks: Perceptual hierarchization or working memory deficit? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40(5):743–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottron L, Burack JA, Iarocci G, Belleville S, Enns JT. Locally oriented perception with intact global processing among adolescents with high-functioning autism: Evidence from multiple paradigms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44(6):904–913. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottron L, Dawson M, Soulières I, Hubert B, Burack JA. Enhanced perceptual functioning in autism: An update, and eight principle of autistic perception. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2006;36(1):27–43. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-0040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piven J, Bailey J, Ranson BJ, Arndt S. An MRI study of the corpus callosum in autism. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154(8):1051–1056. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.8.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley M, Cordes D, Wendt G, Turski P, Moritz C, Haughton V, et al. Effect of focal and nonfocal cerebral lesions on functional connectivity studied with MR imaging. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2001;22(2):294–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ring HA, Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Williams SCR, Brammer M, Andrew C, et al. Cerebral correlates of preserved cognitive skills in autism: A functional MRI study of Embedded Figures Task performance. Brain. 1999;122(7):1305–1315. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.7.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah A, Frith U. An islet of ability in autistic children: a research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1983;24(4):613–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1983.tb00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal CN, Nicolson R, De Vito T, Hayashi KM, Drost DJ, Williamson PC, Rajakumar R, et al. Mapping corpus callosum deficits in autism: An index of aberrant cortical connectivity. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;60(3):218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]