Abstract

Purpose

Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP) is known to have a steep learning curve and, as a result, its clinical usage has limitations. The purpose of this study was to analyze the learning curve and early complications following the HoLEP procedure.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective analysis was performed on 161 patients who had undergone the HoLEP procedure for lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) from July 2008 to September 2009. The procedure was done by two surgeons. Perioperatively, enucleated tissue weight, enucleation time, morcellation time, enucleation ratio (enucleation weight/transitional zone volume), and enucleation efficiency (enucleated weight/enucleation time) were analyzed, and early complications were assessed.

Results

Mean enucleation time, morcellation time, and enucleation ratio were 61.3 min (range, 10-180 min), 12.3 min (range, 2-60 min), and 0.66 (range, 0.07-2.51), respectively. In terms of efficiency, enucleation efficiency was 0.32 g/min (range, 0.02-1.25 g/min) and morcellation efficiency was 1.73 g/min (range, 0.1-7.7 g/min). Concerning the learning curve, enucleation efficiency was stationary after 30 cases (p<0.001), morcellation efficiency reached a learning curve at 20 cases (p=0.032), and enucleation ratio had no learning curve in this study. There were several cases of surgery-related complications, including bladder mucosal injury by the morcellator (13%), capsular injury during enucleation (7%), and conversion to a conventional resectoscopy procedure (15%), which showed a reduction in incidence with time.

Conclusions

The learning curve of HoLEP is steep; however, it can be overcome gradually. Further study is necessary with respect to long-term postoperative follow-up.

Keywords: Holmium, Lasers, Learning, Prostate, Prostatic hyperplasia

INTRODUCTION

Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP) allows a safe and effective treatment for bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) due to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Relatively less morbidity can be observed compared with other modalities in previous literature [1]. Comparison with conventional treatment modalities shows excellent hemostatic properties and less electrolyte deterioration [2-4]. The effectiveness of HoLEP has already been declared, which enables its substitution for open prostatectomy [5,6].

Since the first description of HoLEP in 1995 by Gilling, the technique of laser prostatectomy has been evolving [7]. Years later, the concept of morcellation was adopted and the technique applied to patients with BOO [8]. Recently, HoLEP was introduced in Korea for the surgical treatment of symptomatic BPH. Although the technique has been refined and its popularity has increased, HoLEP has major impediments to widespread application. HoLEP requires considerable endoscopic technique and seems to be difficult to learn. The prolonged learning curve has slowed its acceptance in the urological community [9].

There is some literature about the learning curve of HoLEP [9,10], but this is the first learning curve analysis in Korea. In this study, we examined the learning curve of experienced surgeons as well as the efficiency of HoLEP in a 1-year experience.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Two experienced urological surgeons (SJO, JSP) who were familiar with transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) performed the HoLEP procedure for symptomatic BPH patients over 1 year. The first case of HoLEP was performed in July 2008. There was no mentor with whom to discuss the procedure at the beginning, and video clips of operations by foreign experts were observed. From July 2008 to September 2009, 161 patients underwent HoLEP operation by 2 surgeons independently.

1. Perioperative evaluation

All patients were evaluated preoperatively with serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA), transrectal ultrasound (TRUS), digital rectal examination (DRE), urinalysis, and International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS). Uroflowmetry (UFM) and postvoid residual urine (PVR) measurement by ultrasound were performed. Perioperatively, enucleation time and morcellation time were recorded and the weight of retrieved tissue was measured. IPSS, UFM, and PVR were checked during follow-up at 1, 3, and 6 months postoperatively, and serum PSA and postoperative TRUS measurements were done at 3 months.

2. Surgical technique

Spinal anesthesia was usually preferred. Procedures were not different from those previously described in the literature [8]. We used mainly three-lobe techniques. The energy source was an 80 W holmium:YAG laser with a 550 µm laser fiber (Lumenis®). A 26 Fr resectoscope (Karl Storz™) with a laser bridge was used. Irrigation with normal saline solution was performed continuously. During the enucleation process, the energy power was set at 2 J and 50 Hz, and was sometimes changed to 2 J 40 Hz for hemostasis. Enucleated tissue was morcellated with a VersaCut morcellator (Lumenis®) introduced through a 0'degree nephroscope. Lubricants were applied on the scope intermittently throughout the procedure. At the end of surgery, a 22 Fr 3-way urethral Foley catheter was placed in situ for postoperative continuous irrigation. In general, the flow of irrigation fluid was reduced gradually and then cut off the next morning and the urethral catheter was removed after confirming the cessation of hematuria.

3. Analysis

This study was approved by an ethical committee. Patient demographics and perioperative and follow-up data were analyzed by using SPSS ver. 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). To assess the impact of the learning curve on procedure outcome, procedure efficacy (enucleation ratio) and efficiency were analyzed for the best cutoff point of a stationary state. We divided patients into the first 30 cases, second 30 cases, and the remainder for analyzing enucleation ratio, enucleation efficiency, and complications, whereas groups of 20 cases were used to analyze morcellation efficiency. The postoperative outcomes of the surgery were compared among the several divided groups by using the Pearson chi-square test, with significance considered at p<0.05. The effect of the learning curve on enucleation and morcellation efficiency was analyzed with one-way analysis of variance.

RESULTS

The mean patient age was 67.7 years (range, 51-86 years) old, and mean prostate volume and transitional volume were 51.6 g (range, 29-162 g) and 26.3 g (range, 4-107 g), respectively. Mean enucleation time was 61.3 min (range, 10-180 min), and mean morcellation time was 12.3 min (range, 2-60 min). Considering operative efficacy, the enucleation volume compared to prostate transitional volume (enucleation ratio=% of retrieved tissue=enucleation weight/transitional zone volume) was 0.66 (range, 0.07-2.51). The mean enucleation efficiency (retrieved tissue weight/enucleation time, g/min) was 0.32 g/min (range, 0.02-1.25 g/min), and mean morcellation efficiency (retrieved tissue weight/morcellation time) was 1.73 g/min (range, 0.1-7.7 g/min) (Table 1).

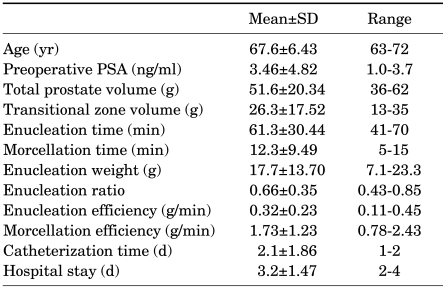

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics and perioperative results (n=161)

PSA: prostate-specific antigen

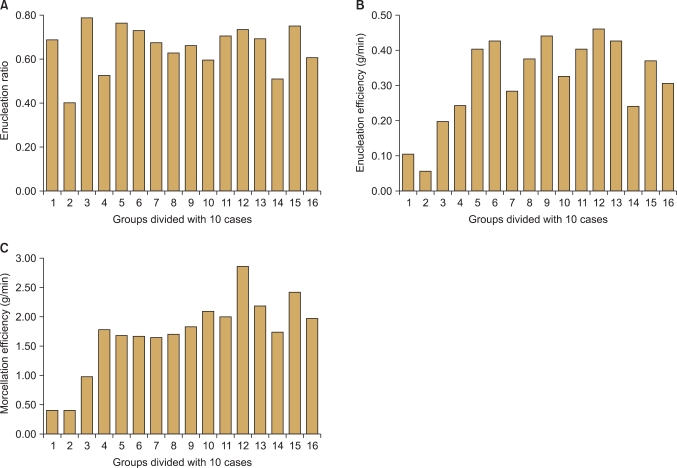

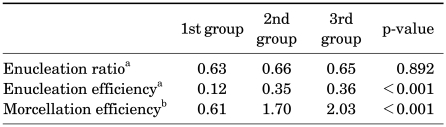

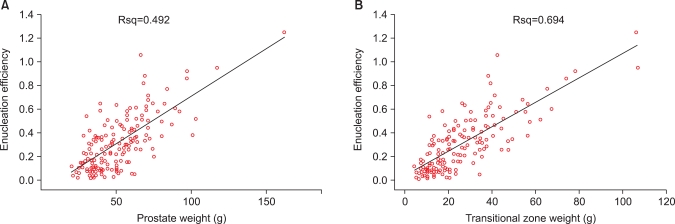

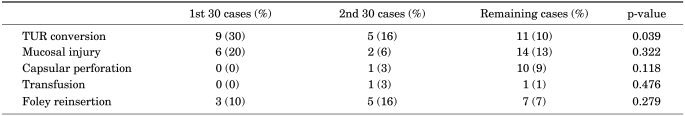

There were gradual improvements in operative parameters (Fig. 1). The comparison of enucleation efficiency among chronologically divided groups showed there was a certain cutoff point at which operators could perform enucleation securely. After 30 cases, we reached a stable enucleation state (p<0.001). In terms of morcellation efficiency, 20 cases were required for reaching a learning curve (p=0.032) (Table 2, Fig. 2). Furthermore, procedure efficiency increased proportionally with prostate weight (Fig. 3).

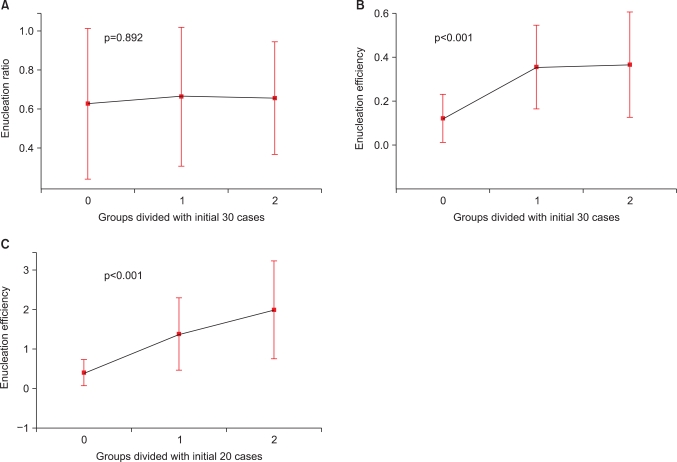

FIG. 1.

Relationship between groups of cases divided by 10 consecutive patients and efficacy of enucleation (A), efficiency of enucleation (B), and efficiency of morcellation (C). The efficiency of each procedure was calculated as weight of removed tissue in g/min.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of operative efficiency parameters

a: groups divided by initial 30 cases, b: groups divided by initial 20 cases

FIG. 2.

Comparison of operative efficiency between divided cases. Groups of enucleation ratio (A) and enucleation efficiency (B) were divided into the initial 30 cases, 2nd 20 cases, and the latter; groups of morcellation efficiency (C) were divided into the initial 20 cases, 2nd 20 cases, and the latter. Enucleation ratio was calculated by % of retrieved tissue=retrieved tissue weight/transitional zone volume, enucleation efficiency was retrieved tissue weight/enucleation time (g/min), and morcellation efficiency was retrieved tissue weight/morcellation time (g/min). Error bars indicate standard deviation.

FIG. 3.

Scatterplots showing the effect of prostate volume in g on holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP) efficiency in g/min. Enucleation efficiency per total prostate volume (A), enucleation efficiency per transitional zone volume (B).

Occasionally, intra-operative complications occurred. With a cutoff of the initial 30 cases, TURP conversion rates were 30% vs. 12% (p=0.015, odds ratio [OR]: 0.33), respectively; mucosal injury rates were 20 vs. 12 (p=0.263, OR: 0.56); capsular perforation rates were 0 vs. 8.4 (p=0.1); and transfusion rates were 0 vs. 1.5 (p=0.494) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Perioperative and immediate complications

TUR conversion: transurethral conversion

DISCUSSION

Despite outstanding hemostatic properties, lower morbidity, and greater efficacy compared with TURP, HoLEP has a major drawback, which is that this promising technique is difficult to learn. A significantly longer adaptation time is required compared with TURP, especially for novices. The enucleation procedure is somewhat difficult for certain surgeons. Identification of the surgical plane between prostate adenoma and prostate capsule requires certain experiences, as other surgeries do.

It is known that KTP has no distinct learning curve [11]. However, some surgeons employing surgical techniques like enucleation insist that it needs a learning curve [12]. Robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy (RALP) for prostate cancer needs a learning curve, and it depends on technical skills and a self-perceived state of being expertise. Prior retropubic radical prostatectomy expertise allows rapid adaptation to RALP [13]. This may be similar to the relationship between the transurethral resection (TUR) procedure and HoLEP.

As a general rule, the learning curve is regarded as the period required for the surgeon to be comfortable with the surgery and is usually represented by the number of cases. It is substantially a self-assumed point [13]. For the HoLEP procedure, some groups mentioned that 20 cases could be sufficient, whereas others demonstrated that at least 50 cases were necessary to achieve basic competence [9,10]. Other groups have inquired into the primary factor that made the procedure easier, such as its intrinsic properties or circumstances of the novice surgeon [8,10]. Objective parameters of the learning curve that should be considered are operation time, efficiency, reduced complications, and postoperative outcome of the surgery. The present study focused on operative efficiency, which primarily makes the surgeon confident of adaptation to the procedure. We calculated enucleation efficiency, morcellation efficiency, HoLEP efficacy (enucleation ratio), and perioperative complication rates.

During the HoLEP procedure, a subjectively perceived comfortable state can be estimated by the velocity of the operation. Our results showed gradual improvement in efficiency (Fig. 1). We continued to divide the patients into several groups. For enucleation efficiency, subgroups consisted of the initial 30 cases, the next 30 cases, and the others, whereas for morcellation efficiency, the initial 20 cases made up a subgroup. In these groups, we determined the minimum number of cases that could indicate a statistically significant cutoff point. Enucleation efficiency was achieved after 30 cases, and morcellation efficiency after 20 cases. With these results, we assumed the cutoff point concerning operation speed to be about 20 to 30 cases, which corresponded with a previous study [10]. Previous study groups mentioned that morcellation efficiency improvement was too slow to perceive [9,10]. In our study, we could find a cutoff point for morcellation efficiency with statistical significance. Indeed, adaptation to morcellation requires time because it is a somewhat new modality to a TUR-experienced surgeon. In this study, 20 cases were required to adapt to the morcellation procedure.

In general, surgeons start an operation with an easy case, which is followed by difficult ones. Learning curve migration from small prostate cases to large prostate cases is another one. In our data, prostate volume was larger during the latter period than in the early ones, but this difference was not statistically significant. In our experience, there was a trend for the enucleation ratio to be improved. In addition, enucleation efficiency increased in proportion to prostate weight.

Perioperative complications can be a reference of the learning curve. The rates of conversion to TURP (TUR conversion), mucosal injury, transfusion, and urethral catheter reinsertion improved as cases accumulated. This observation could be assumed to represent maturation of the surgeon's skill. Therefore, we analyzed the rate of complications in each group divided by the initial 30 cases, which was assumed to be the self-confidence point for enucleation. In particular, TUR conversion, which includes TUR set substitution for surface coagulation, was significantly reduced (p=0.039). This means that the operator had attained confidence with high efficiency and low complications during enucleation with the holmium laser. However, capsular perforation and incontinence increased. This may also be attributed to the operator's confidence, which resulted in enucleation being performed more rapidly.

The concept of the learning curve originally implies that it should be overcome. Some investigators conceived that HoLEP learning curve contains self-consciousness such as less bleeding and rapid operation, which make the surgeon improved [10]. Others emphasized the responsibility of a mentor who can teach basic technique, lead to a true plane, discuss difficult cases, confirm an alternative choice, and fundamentally encourage the trainee [9]. Before the initiation of HoLEP, review of expertise video recording can give the surgeon a quick understanding of the prostate and HoLEP procedure. Furthermore, as endoscopic surgeons do, review of recordings of the surgeon's own surgical procedures provides a good opportunity to correct flaws. If support is available, a training center that has facilities such as a dry laboratory or animal laboratory in a laparoscopic or robotic surgery environment can provide desirable results.

The learning curve for HoLEP can be not only a subjectively perceived time period but also an objectively measured value [13]. Enucleation and morcellation efficiency can be a certain index of expertise. Furthermore, other parameters such as the complication rate and postoperative voiding improvement should ultimately be considered. However, in this study, we did not analyze overall clinical characteristics and postoperative results, which we hope to report in further studies. Although the learning curve is steep and the true plateau of expertise can never be reached, gradual improvement can be achieved as surgical volume accumulates.

CONCLUSIONS

HoLEP is known to be a safe and feasible procedure. Although the learning curve is steep, it can be gradually overcome. Additional studies are necessary with respect to long-term clinical outcomes.

Footnotes

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Chilton CP, Mundy IP, Wiseman O. Results of holmium laser resection of the prostate for benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Endourol. 2000;14:533–534. doi: 10.1089/end.2000.14.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moody JA, Lingeman JE. Holmium laser enucleation for prostate adenoma greater than 100 gm: comparison to open prostatectomy. J Urol. 2001;165:459–462. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200102000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westenberg A, Gilling P, Kennett K, Frampton C, Fraundorfer M. Holmium laser resection of the prostate versus transurethral resection of the prostate: results of a randomized trial with 4-year minimum long-term followup. J Urol. 2004;172:616–619. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000132739.57555.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montorsi F, Naspro R, Salonia A, Suardi N, Briganti A, Zanoni M, et al. Holmium laser enucleation versus transurethral resection of the prostate: results from a 2-center, prospective, randomized trial in patients with obstructive benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2004;172:1926–1929. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000140501.68841.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuntz RM, Lehrich K. Transurethral holmium laser enucleation versus transvesical open enucleation for prostate adenoma greater than 100 gm: a randomized prospective trial of 120 patients. J Urol. 2002;168:1465–1469. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64475-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elzayat EA, Elhilali MM. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP): the endourologic alternative to open prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2006;49:87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilling PJ, Cass CB, Malcolm AR, Fraundorfer MR. Combination holmium and Nd:YAG laser ablation of the prostate: initial clinical experience. J Endourol. 1995;9:151–153. doi: 10.1089/end.1995.9.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilling PJ, Kennett K, Das AK, Thompson D, Fraundorfer MR. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP) combined with transurethral tissue morcellation: an update on the early clinical experience. J Endourol. 1998;12:457–459. doi: 10.1089/end.1998.12.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah HN, Mahajan AP, Sodha HS, Hegde S, Mohile PD, Bansal MB. Prospective evaluation of the learning curve for holmium laser enucleation of the prostate. J Urol. 2007;177:1468–1474. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seki N, Mochida O, Kinukawa N, Sagiyama K, Naito S. Holmium laser enucleation for prostatic adenoma: analysis of learning curve over the course of 70 consecutive cases. J Urol. 2003;170:1847–1850. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000092035.16351.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matlaga BR, Kim SC, Kuo RL, Watkins SL, Lingeman JE. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate for prostates of > 125 mL. BJU Int. 2006;97:81–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.05898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perlmutter AP, Schulsinger DA. The "Wedge" resection device for electrosurgical transurethral prostatectomy. J Endourol. 1998;12:75–79. doi: 10.1089/end.1998.12.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herrell SD, Smith JA., Jr Robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy: what is the learning curve? Urology. 2005;66(5 Suppl):105–107. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.06.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]