Abstract

DNA isolated from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue is often fragmented and cross-linked and is therefore difficult to genotype. To enable this source of DNA for genotyping analysis using Taqman probes, we tested whether enrichment of the target genes would increase the amount of available DNA. For enrichment of the target genes, we used preamplification by means of diluted Taqman assays. To establish the appropriateness of preamplification, we used DNA extracted from paraffin-embedded tissue and compared the genotyping results of a series of single nucleotide polymorphisms assessed in DNA samples with and without preamplification. In a subset of patients, DNA was isolated from both blood and FFPE tissue to test the reliability of genotyping results derived after preamplification. We found an increase in call rate after preamplification and a convincing concordance in genotype. Based on our findings, we can safely conclude that preamplification of DNA isolated from paraffin-embedded tissue is a valuable and reliable method to optimize genotyping results.

For most genotyping assays, high-quality DNA is preferred to guarantee reliable and reproducible results.1 DNA is preferably isolated from EDTA anticoagulated blood, because heparin may interfere in the polymerase chain reaction (PCR).2 For diagnostic testing, it is usually not a problem to obtain fresh blood, although in neonates cheek swabs may be preferred. However, if fresh EDTA anticoagulated blood is not available, for instance in retrospective studies, archived biological samples may also have to be used. Archived biological samples may consist of frozen EDTA anticoagulated blood, serum/plasma or formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue, however the DNA yield and quality from such sources may be poor (reviewed in Ref. 3). Consequently, the success rate of genotyping DNA purified from such samples is low. Due to formalin fixation, DNA isolated from FFPE tissue, is cross linked and therefore difficult to amplify by PCR.4,5 In addition, such DNA is fragmented into pieces with a length of a few hundred bp.6 Because this fragmentation is random, it is difficult, if not impossible, to predict whether the target sequence can be efficiently amplified.

To make DNA isolated from FFPE tissue more suitable for genotyping studies, we tested the feasibility of a preamplification step using single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP)-specific Taqman assays. The preamplification step was used to enrich for sequences around target SNPs and consisted of a PCR reaction containing all Taqman assays (diluted) in one single tube per sample. This step was performed before Taqman analysis. The preamplification procedure was originally developed to genotype small amounts of complementary DNA (reverse transcribed RNA) and has successfully been used in expression studies7 but also in genotyping trace amounts of DNA isolated from plasma or dried blood.8 We compared the results obtained with and without the preamplification step on DNA isolated from FFPE tissue. For a subset of samples, we were able to compare genotypes in DNA derived from blood and FFPE tissue. In addition, we tested whether preamplification affects the results through abundance of one allele in genes with copy number variants (CNV). To our knowledge, this is the first report describing successful genotyping of DNA derived from FFPE tissue using SNP specific preamplification, making FFPE tissue an interesting source for large retrospective genetic or pharmacogenetic studies.

Materials and Methods

DNA Source

From the Tamoxifen Exemestane Adjuvant Multinational (TEAM) study, a large prospective trial comparing different adjuvant hormonal therapies in breast cancer,9 FFPE tissues of 755 patients were collected from whom no other DNA source was available.

EDTA anticoagulated blood was available from two other prospective trials: the CAIRO1 study10 and the CYPTAM study (http://www.trialregister.nl/trialreg/admin/rctview.asp?TC=1509; last accessed on May 17, 2010).

DNA Isolation

To extract DNA from FFPE tissue, three slides of 20 μm were incubated overnight at 50°C in 500 μl lysis buffer (NH4CL 8.4 g/L; KHCO3 1 g/L; proteinase K 0.25 mg/ml). The following day, 300 μl was taken to extract DNA with Maxwell forensic DNA isolation kit (Promega, Leiden, The Netherlands). DNA was extracted from EDTA anticoagulated blood by Magna Pure Compact (Roche, Almere, The Netherlands). Of 22 patients from the CAIRO1 study, DNA was extracted from both FFPE tissue and EDTA anticoagulated blood by the respective methods above.

Genotyping

We used a total of 39 different genotyping Taqman assays, frequently used in pharmacogenetic studies, to genotype a total of 823 samples. All assays were designed by and obtained from Applied Biosystems (Carlsbad, CA). All samples were genotyped on the Taqman 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Nieuwerkerk aan den IJssel, The Netherlands) or on the Biomark (Fluidigm, San Francisco, CA) according to standard procedures.

Preamplification

Preamplification was performed according to the manufacturer's instruction. Briefly, to 1.25 μl of DNA, a dilution of all Taqman assays (final concentration 0.2×) in a total volume of 1.25 μl and 2.5 μl of preamplification mastermix (Applied Biosystems) was added and amplified on a conventional PCR machine (18 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C and 4 minutes at 60°C). This mixture was diluted 5-times; 1 μl or 2.5 μl were used for Taqman or Biomark analysis, respectively.

Copy Number Variation of CYP2D6 Gene

From the CYPTAM study, 10 ng DNA isolated from EDTA anticoagulated blood was taken (n = 46) for preamplification and genotyped for CYP2D6*2, *3, *4, *6, *10,*14. The results were subsequently compared with that analyzed on Amplichip11 (Roche, Almere, The Netherlands).

Limited Dilution

DNA isolated from whole blood was serially diluted to a final concentration of 9.8 pg/μl. For one SNP, the detection limit was determined with and without preamplification.

Results

FFPE Tissue DNA

For the TEAM study, only FFPE tissues were available from which DNA could be extracted. Initially, we tested 80 samples for the SNPs rs1799853, rs1801133, and rs11615 using Taqman 7500 Real-Time PCR system, because these assays have already been used successfully in our department. The results were unsatisfactory because the number of successful genotyped samples was low, due to high Cq (Quantification Cycle) values (>35) and consequently low fluorescence. Using more input DNA (1–8 μl) increased the callrate (which is the percentage of samples that were successfully genotyped for a SNP) and reliability (Cq <35) but limited the number of SNPs to be tested, simply because of limited DNA mass (data not shown). Testing some of these samples (n = 46) on the Biomark system, using the Biomark 48.48 array, did not yield any genotype calling. However, after preamplification of 31 SNPs we found callrates for all available samples (n = 755) varying from 84% to 100% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Call Rates of FFPE DNA after Preamplification (n = 755)

| Gene | SNP | Call Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| CYP2C9*2 | rs1799853 | 98 |

| NR1I3 | rs2307424 | 93 |

| UGT1A8*2 | rs1042597 | 96 |

| NR1I3 | rs2307418 | 99 |

| CYP2D6*4 | rs3892097 | 92 |

| CYP2C9*3 | rs1057910 | 95 |

| NR1I3 | rs4073054 | 98 |

| CYP2D6*6 | rs5030655 | 84 |

| CYP3A5*3 | rs776746 | 98 |

| UGT2B7 | rs7438135 | 98 |

| CYP2D6*2 | rs16947 | 95 |

| CYP2D6*10 | rs1065852 | 90 |

| CYP2B6*5 | rs3211371 | 94 |

| ESR1 | rs2234693 | 93 |

| NR1I2 | rs2276707 | 100 |

| CYP2D6*41 | rs28371725 | 93 |

| CYP2B6*6 | rs2279343 | 86 |

| ESR1 | rs9340799 | 91 |

| NR1I2 | rs6785049 | 99 |

| CYP2D6*14 | rs5030865 | 84 |

| CYP2B6*8 | rs12721655 | 96 |

| UGT1A4*2 | rs6755571 | 94 |

| NR1I2 | rs2276706 | 97 |

| CYP2C19*2 | rs4244285 | 86 |

| UGT2B15*2 | rs1902023 | 92 |

| UGT1A4 | rs3732218 | 98 |

| NR1I2 | rs1054190 | 98 |

| CYP2C19*17 | rs12248560 | 99 |

| NR1I2 | rs3814055 | 99 |

| UGT1A4 | rs3732219 | 99 |

| NR1I2 | rs1054191 | 98 |

FFPE Tissue DNA Compared to Whole Blood DNA

DNA of 22 patients was available from both FFPE tissue and whole blood. Using Taqman analysis, 8 SNPs were determined on both types of DNA with and without preamplification to compare genotypes of FFPE and whole blood from the same patients. We found 100% concordance in genotype between whole blood DNA (preamplified or nonpreamplified) and FFPE tissue derived DNA that had been preamplified. For nonpreamplified genotypes, four mismatches were found in three SNPs when compared to whole blood DNA (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mismatches of Genotypes Obtained Directly and after Preamplification of FFPE DNA, Compared with Genotypes Established in Whole Blood (n = 22)

| Gene | rs number | FFPE (Direct) | FFPE (Preamplified) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABCB1 | rs1128503 | 1 | 0 |

| ABCG2 | rs2231142 | 0 | 0 |

| P53 | rs1042522 | 1 | 0 |

| GSTP1 | rs1695 | 0 | 0 |

| ERCC2 | rs1799793 | 2 | 0 |

| ERCC2 | rs13181 | 0 | 0 |

| XRCC1 | rs25487 | 0 | 0 |

| RFC | rs1051266 | 0 | 0 |

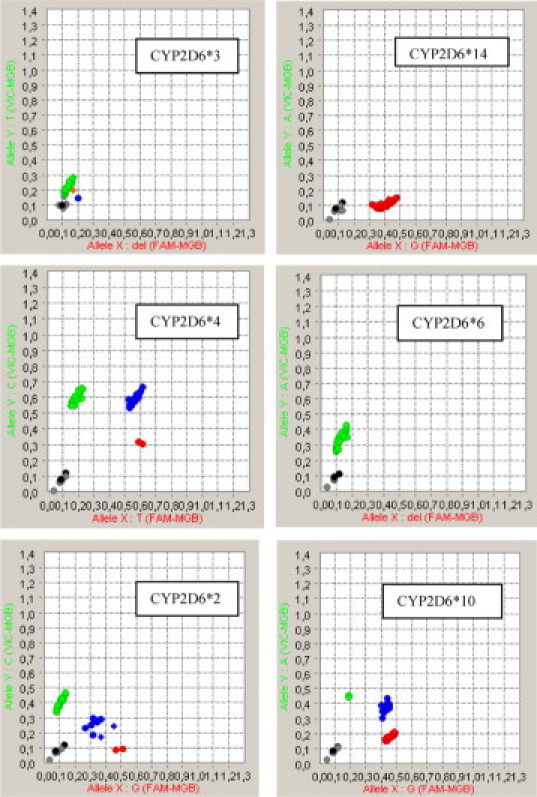

Copy Number Variation

To test whether preamplification affects the genotype in case of CNV, we tested SNPs in the CYP2D6 gene of which CNV is relatively common.12,13 Copy number variation might result in abundance of one allele that possibly overrules the presence of the other allele. We tested 46 samples (whole blood DNA) that were genotyped by Amplichip. Of these samples, four were found to have multiple copies of the CYP2D6 gene. We preamplified these 46 DNA samples and analyzed these on Biomark for CYP2D6*2, *3, *4, *6, *10,*14. No difference in genotype were found for these 46 samples when established by Amplichip or after preamplification and analyzed by Biomark (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Allelic discrimination plots of preamplified DNA isolated from whole blood on the BioMark 48.48 array.

DNA Concentration Detection Limit

The reliability of the genotype derived after preamplification of trace amounts of DNA was determined by limiting dilution of three DNA samples isolated from EDTA blood. Figure 1 shows a detection limit (ie, Cq >35) for nonpreamplified DNA of 312.5 pg, while the genotype of even 9.8 pg could easily be established after preamplification (Cq = 22). No difference in genotype was observed.

Figure 1.

Cq values of diluted DNA, directly and preamplified.

Discussion

Several methods and different sources of DNA are available for genotyping assays. Taqman-based genotyping analysis is commonly used to genotype samples. Fluidigm has launched the Biomark to enable simultaneously screening of 48 SNPs in 48 samples in one run using Taqman assays. The source and consequently the quality of DNA remains an important factor to obtain high success rates of genotype calling, irrespective of the chosen method. Good quality DNA can be isolated from fresh EDTA anticoagulated blood or from saliva.14 For many retrospective studies, however, no material other than serum, plasma, or FFPE tissue is available. The quality of DNA isolated from such material may be poor, and screening for several SNPs may result in low success rates.

In this report we describe the use of an allele-specific preamplification method that improves the quality of results when using DNA isolated from FFPE tissue. This preamplification has already been applied to genotype trace amounts of DNA isolated from plasma or dried blood.8 We compared genotypes obtained from DNA isolated from whole blood and FFPE tissue, with and without preamplification. On 22 samples from which DNA from both FFPE and whole blood was available, we could compare concordance between obtained genotypes with and without using the preamplification step. We established the detection limit by serial dilution, and, in addition, we genotyped whole blood DNA for SNPs in the CYP2D6 gene of which multiple copies are familiar. In four patients with multiple copies of CYP2D6 the other nonamplified allele could also be detected on Biomark after preamplification. Although these results are based on a limited number of patients, we believe this could suggest that preamplification of SNPs in case of CNV does not alter genotyping results. However, further study is needed to corroborate our findings.

For FFPE tissue DNA (n = 755) we obtained callrates for 31 SNPs differing from 84 to 100%, which could not have been obtained by analysis using Taqman 7500 Real-Time PCR system due to limiting DNA mass. In addition, for 22 samples we compared genotypes of eight other SNPs, obtained with and without preamplification, of FFPE tissue DNA with whole blood DNA. Between these two types of DNA, no differences in genotype calling were observed. However, four mismatches were observed with FFPE DNA when no preamplification was performed. Although these genotypes were automatically called by Taqman software, the absolute quantification plots indicate that PCR efficiency in these samples was low and therefore less reliable.

In summary, using a preamplification step enables the use of DNA isolated from FFPE. Because only a small volume is required for this step, and many SNPs can be preamplified in one reaction, there will be enough DNA left over for future studies. Preamplification yielded reliable results for even 9.8 pg of DNA, as was established by limited dilution, and this makes this method suitable for genotyping trace amounts of DNA. Although we did not test it, we believe that genotyping of fetal DNA, isolated from maternal plasma (of which 60% is fragmented to <100-bp),15 might benefit from preamplification as well. The same accounts for trace amounts of DNA isolated from serum of which archiving is widely practiced in research and clinical domains.16 From our findings we conclude that preamplification is a reliable step to raise call rates when using FFPE tissue as the only source of DNA.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Marion Blonk for checking the manuscript for spelling and grammar.

Footnotes

The authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Farrugia A, Keyser C, Ludes B. 2009. Efficiency evaluation of a DNA extraction and purification protocol on archival formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue. Forensic Sci Int. 2010;194:e25–e28. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beutler E, Gelbart T, Kuhl W. Interference of heparin with the polymerase chain reaction. Biotechniques. 1990;9:166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okello JB, Zurek J, Devault AM, Kuch M, Okwi AL, Sewankambo NK, Bimenya GS, Poinar D, Poinar HN. Comparison of methods in the recovery of nucleic acids from archival formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded autopsy tissues. Anal Biochem. 2010;400:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feldman MY. Reactions of nucleic acids and nucleoproteins with formaldehyde. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1973;13:1–49. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehmann U, Kreipe H. Real-time PCR analysis of DNA and RNA extracted from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded biopsies. Methods. 2001;25:409–418. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wickham CL, Boyce M, Joyner MV, Sarsfield P, Wilkins BS, Jones DB, Ellard S. Amplification of PCR products in excess of 600 base pairs using DNA extracted from decalcified, paraffin wax embedded bone marrow trephine biopsies. Mol Pathol. 2000;53:19–23. doi: 10.1136/mp.53.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li J, Smyth P, Cahill S, Denning K, Flavin R, Aherne S, Pirotta M, Guenther SM, O'Leary JJ, Sheils O. Improved RNA quality and TaqMan Pre-amplification method (PreAmp) to enhance expression analysis from formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) materials. BMC Biotechnol. 2008;8:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-8-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catsburg A, van der Zwet WC, Morre SA, Ouburg S, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Savelkoul PH. Analysis of multiple single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) on DNA traces from plasma and dried blood samples. J Immunol Methods. 2007;321:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasenburg A, van de Velde CJH, Seynaeve C, Rea DW, Vannetzel J, Paridaens R, Markopoulos C, Hozumi Y, Putter H, Jones SE. Five years of exemestane as initial therapy compared to tamoxifen followed by exemestane for a total of 5 years: the TEAM trial, a prospective, randomized, phase III trial in postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive early breast cancer. European Journal of Cancer. 2010;Supplement 8:62. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koopman M, Antonini NF, Douma J, Wals J, Honkoop AH, Erdkamp FL, de Jong RS, Rodenburg CJ, Vreugdenhil G, Loosveld OJ, van Bochove A, Sinnige HA, Creemers GJ, Tesselaar ME, Slee PH, Werter MJ, Mol L, Dalesio O, Punt CJ. Sequential versus combination chemotherapy with capecitabine, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin in advanced colorectal cancer (CAIRO): a phase III randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:135–142. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heller T, Kirchheiner J, Armstrong VW, Luthe H, Tzvetkov M, Brockmoller J, Oellerich M. AmpliChip CYP450 GeneChip: a new gene chip that allows rapid and accurate CYP2D6 genotyping. Ther Drug Monit. 2006;28:673–677. doi: 10.1097/01.ftd.0000246764.67129.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feuk L, Carson AR, Scherer SW. Structural variation in the human genome. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:85–97. doi: 10.1038/nrg1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ingelman-Sundberg M. Genetic polymorphisms of cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6): clinical consequences, evolutionary aspects and functional diversity. Pharmacogenomics J. 2005;5:6–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Ji C. An application of salivary DNA in twin research of Chinese children. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2008;11:546–551. doi: 10.1375/twin.11.5.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koide K, Sekizawa A, Iwasaki M, Matsuoka R, Honma S, Farina A, Saito H, Okai T. Fragmentation of cell-free fetal DNA in plasma and urine of pregnant women. Prenat Diagn. 2005;25:604–607. doi: 10.1002/pd.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirtzlin I, Dubreuil C, Préaubert N, Duchier J, Jansen B, Simon J, De Faria Lobato P, Perez-Lezaun A, Visser B, Williams GD, Cambon-Thomsen A, EUROGENBANK Consortium An empirical survey on biobanking of human genetic material and data in six EU countries. Eur J Hum Genet. 2003;11:475–488. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]