Abstract

Objective:

To identify risks factors associated with pressure ulcers (PrU) after spinal cord injury (SCI) by examining race and indicators of socioeconomic status (measured by income and education). We hypothesize African Americans will have a greater risk for PrUs than whites, but this relationship will be mediated by the 2 socioeconomic status indicators.

Design:

Cohort study.

Setting:

A large rehabilitation hospital in the southeastern US.

Participants:

1,466 white and African American adults at least 1-year post-traumatic SCI.

Outcome Measures:

(a) PrUs in the past year, (b) current PrU, (c) surgery to repair a PrU since injury.

Results:

In preliminary analyses, race was significantly associated with having a current PrU and with having surgery to repair a PrU since injury. In multivariable analyses, the relationships of PrU with having a current PrU and with having surgery to repair a PrU were both mediated by income and education such that the relationships were no longer significant. Lower income was associated with increased odds of each PrU outcome. After controlling for other variables in the model, education was associated with increased odds of having a current PrU.

Conclusion:

These findings help clarify the relationships between race and socioeconomic status with PrUs after SCI. Specifically, a lack of resources, both financial and educational, is associated with worse PrU outcomes. These results can be used by both providers and policy makers when considering prevention and intervention strategies for PrUs among people with SCI.

Keywords: Spinal cord injuries, Race, Pressure ulcer, Socioeconomic factors

INTRODUCTION

Pressure ulcers (PrU) are a serious secondary condition that can occur after spinal cord injury (SCI) and have been linked with long-term mortality (1). Pressure ulcers are one of the most common complications occurring among people with SCI (2). Despite extensive literature and research on prevention and treatment, their prevalence is still high (3,4).

Several studies have found a relationship between race/ethnicity and PrUs (5–7). In the general population, African Americans were found at higher risk of mortality from PrUs than whites (8). Although Fuhrer and associates (9) found no differences in the prevalence of PrUs between African Americans and whites, they did find that African Americans were more likely to have severe (stage III or higher) PrUs than whites. Additional studies have found a similar relationship between race and PrU severity (10,11). In the SCI population, Saladin and associates (5) found that American Indians had greater odds of PrUs within the past year than Hispanics and that African Americans and American Indians had greater odds of a current PrU than Hispanics. Whites were included in the study but were not significantly different from Hispanics (the reference group). One study, using a relatively small sample size (n = 64) of veterans with SCI, found that race was the strongest predictor of recurrent PrUs, where African Americans were significantly more likely to have recurrent PrUs than whites (6). Additionally, a study using the SCI Model Systems data found that being African American was a risk factor for stage II or higher PrUs (7). A major limitation of the previous studies is that although all 3 studies in some way examined education in relation to PrU, none took into account income as a possible mediator in the relationship between race and PrUs.

It is important to consider race and socioeconomic status (SES), because, in the US, SES, race, and health have historically been linked to one another. Studies have shown that low SES, including low income, occupation type, and education, is consistently related to reduced access to quality health care (12). Further examination of the problematic health care issues shows that the populations most often affected are minority groups (13). African Americans tend to have less education and lower income and experience poverty at all ages, as opposed to whites (12). This can lead to diminished access to health care, which contributes to the gap in equality between different racial groups and their health outcomes (14). Longitudinal studies have shown that low education typically predicts a decline in health (15). Although literature suggests that education and health care access facilitate better outcomes after an injury, these resources are not always obtainable for people with SCI.

Purpose and Hypotheses

The objective of the current research is to identify risk factors associated with PrUs after SCI by examining race and SES (measured by income and education). We hypothesize that African Americans will have a greater risk for PrUs than whites but that this relationship will be mediated by 2 SES indicators (education and income). A mediational model occurs when an independent variable (race) is associated with an outcome (PrUs), but the relationship disappears after accounting for a mediating variable (SES indicators) (16).

METHODS

After receiving approval from the Institutional Review Board, participants for a mail-in survey were identified through 3 different sources of records at a large specialty hospital in the southeastern US: (a) SCI Model Systems database, (b) Model Systems registry, and (c) outpatient directory. There were 3 inclusion criteria: (a) traumatic SCI, (b) age 18 years or older at assessment, and (c) minimum of 1 year after injury. Of 2,480 potential participants meeting these criteria, 1,549 returned their survey (62.5% response rate). Because nearly all participants were white, or African American, there were insufficient numbers of other racial/ethnic groups for the analysis. Therefore, the sample was reduced to 1,466 after eliminating all non-white and non-African American participants.

Data Collection Procedures

Five weeks before receiving an initial packet of study materials, participants were sent preliminary letters that described the intended research and the method by which they would receive the materials. The initial packet included a letter that described the study and served as implied consent, as well as the survey to be completed and mailed in. If the initial packet was not returned, a second mailing was set in place for all nonrespondents. If the participant did not respond, a phone call was made to engage in active conversation with the potential participant. A third mailing was then used for those participants who had misplaced or accidently discarded the materials but consented by phone to receive another packet.

Measures

Measurements were taken using a mail survey tool. We used a subset of measures from a larger study of protective and risk factors associated with the onset of multiple types of adverse health outcomes and secondary conditions among a large sample of individuals with SCI (17). Specifically for this study, income, education, race, and PrUs were examined.

Our outcome in this study was PrUs, and several items were used to assess this outcome. First, participants were asked, “All totaled, how many different open pressure sores have you had in the past year?” This was dichotomized as none or one or more. Additionally, participants were asked “Do you have at least one open sore right now?” and “Since your injury, how many surgeries have you had to repair pressure sores?” The number of surgeries was dichotomized into none or one or more. We only asked participants to report open PrUs because it might be difficult for some participants to recognize a less severe PrU, especially people with pigmented skin (18). Therefore, all results in this study are referring to open PrUs. This measurement has been used in previous studies of people with SCI (17,19,20).

Biographic (ie, race, gender, age, years after injury, age at injury) and injury characteristics were assessed. Injury severity was categorized as C1–C4, nonambulatory; C5–C8, nonambulatory; noncervical, nonambulatory; and ambulatory regardless of level. Race was categorized as white or African American. There were 2 indicators of SES: education and income. The participant was asked the exact number of years of education he or she had completed. Although we did not explicitly differentiate between full- and part-time education, years of education were anchored with educational milestones (eg, 12 = high school certificate, 16 = 4-year college degree). Participants were asked their annual household income, which was recoded into 3 categories: <$25,000, $25,000–$74,999, and ≥$75,000.

Analysis

Preliminary analyses were used to summarize the participant sample in terms of PrUs and biographic, injury, educational, and SES characteristics. During the preliminary analyses, the χ2 statistic was used to evaluate the statistical significance of categoric variables, whereas the t test was used for continuous variables. The results of these analyses were used in model building.

For the model building, we used multivariable logistic regression with each of 3 outcomes: PrUs in the past year (yes or no), current PrU (yes or no), and ever having had surgery for a PrU (yes or no). All variables were included in the analyses, except for age in the model for PrU in the past year and the PrU surgery model and age at injury in the current PrU model, because these variables were not statistically significant during preliminary analyses. For each model, we used a 2-stage hierarchic model-building strategy. In the first stage of each model (Base), race was entered with the other biographic and injury characteristics (gender, injury severity, years since injury, age at injury). In the second stage (Mediating), SES variables (education, income) were added to the previous model. We used P < 0.05 as the cutoff for statistical significance in the final model.

Finally, interactions between race and income and education were tested in each model (they were not significant). Hosmer-Lemeshow and global χ2 tests were used to assess goodness of fit of the model (21). The C-statistic, measuring area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, was used to assess discriminatory ability (21). Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs are reported.

RESULTS

Descriptive

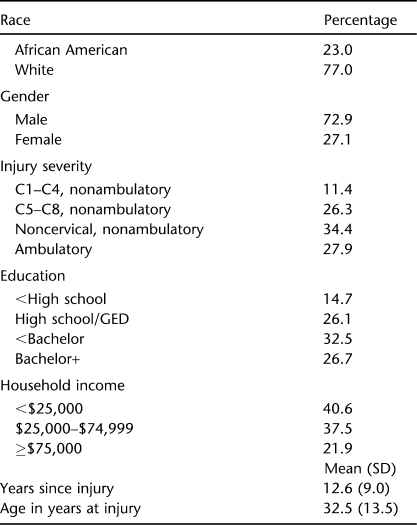

Of 1,466 participants meeting the selection criteria, 23.0% were African American and 72.9% were men (Table 1). Average age at injury was 32.5 years (13.5 years), with the average years since injury being 12.6 (9.0). Just less than 28% (27.9%) were able to ambulate. The remaining nonambulatory participants were nearly equally divided between cervical (37.7% of the sample) and noncervical (34.4% of the sample). Only 26.7% completed a bachelor's degree or higher, 32.5% had completed some education beyond high school, 26.2% reported a high school certificate, and 14.7% did not obtain a high school certificate. Household income ≥$75,000 was reported by 21.9% of participants, and an income <$25,000 was reported by 40.6%.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants

Thirty-nine percent of the participants reported having a PrU in the past year, and 20.4% reported having a current PrU. Additionally, 23.4% had at least one surgery to repair a PrU since his or her SCI.

Because we were testing mediational models, we first assessed the relationship of the mediators (income and education) with race. Both mediators were significantly associated with race [income: χ2 = 117.33, P < 0.0001; education: χ2 = 76.43, P < 0.0001].

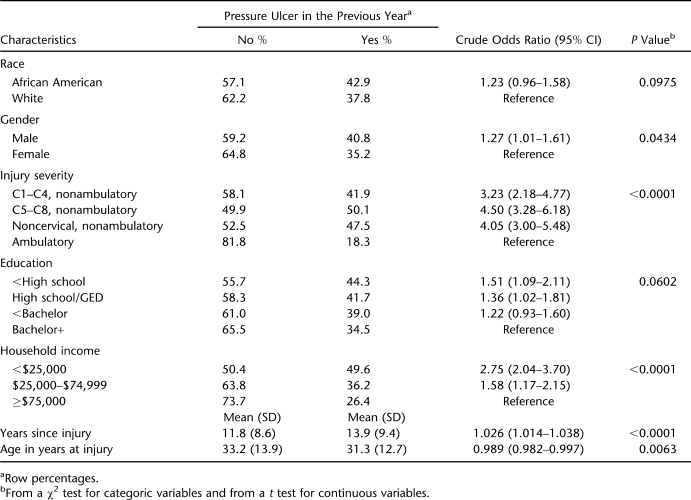

Pressure Ulcer in Past Year

Calculation of the crude OR (no adjustment for other variables) indicated that neither race nor education were significantly associated with having at least one PrU in the past year (Table 2). However, household income was significantly associated, because people with higher household income were less likely to have PrUs in the past year. All other variables were significant, with the exception of age at survey, and thus were included in the final model (Table 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of People With and Without a Pressure Ulcer in the Previous Year

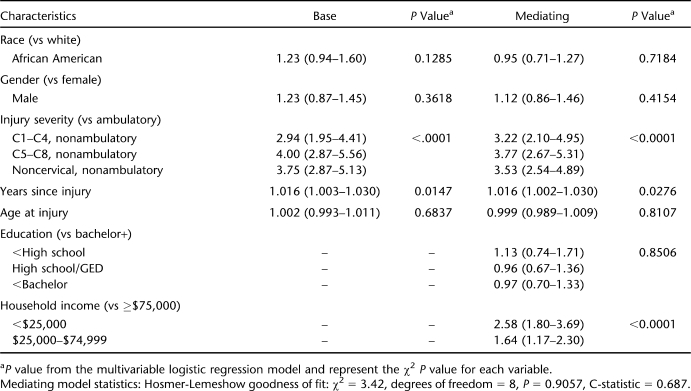

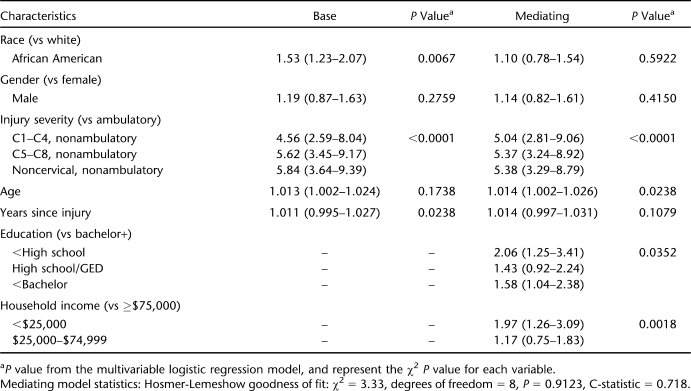

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratios and 95% CIs for Having a Pressure Ulcer in the Past Year

After controlling for other variables in the model, people with <$25,000 in household income per year were 2.58 times as likely to have a PrU in the past year than those who made ≥$75,000 per year (OR = 2.58; 95% CI: 1.80–3.69). Similarly, people who make $25,000 to $74,999 per year were also more likely to have had at least one PrU in the past year (OR = 1.64, 95% CI: 1.17–2.30). People who were nonambulatory were more likely to have PrUs in the past year than those who were ambulatory. Lastly, the more years that had passed since injury, the more likely the participants were to have PrUs in the past year.

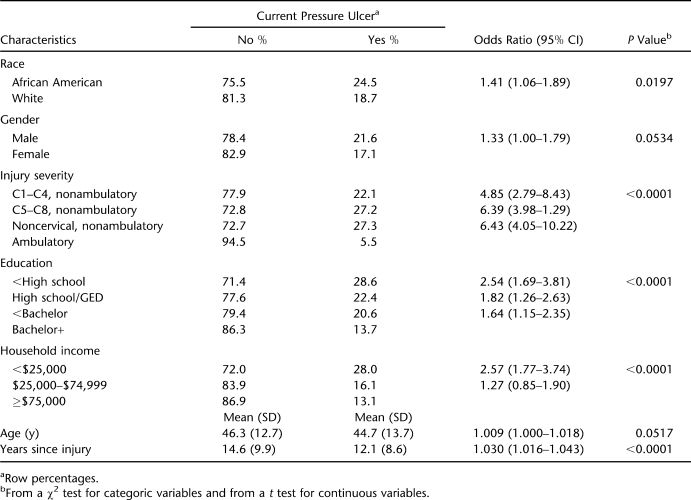

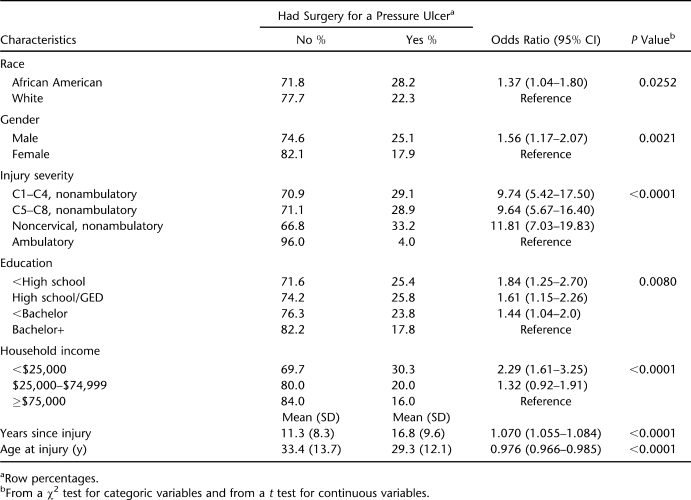

Current Pressure Ulcer

Race, education, and household income were all significantly related to having a current PrU in the univariate analysis (Table 4). Race became nonsignificant when education and income were added to the base model. Education retained a significant relationship with having a current PrU (Table 5), because individuals with less than a high school certificate were 2.06 times more likely to have a current PrU than those with a bachelor's degree or higher (OR = 2.06, 95% CI: 1.25–3.41). Additionally, people whose household income was <$25,000 per year were 1.97 times as likely to have a current PrU than those with ≥$75,000 (OR = 1.97; 95% CI: 1.26–3.09). Of the other predictors, people of older age were more likely to have a current PrU.

Table 4.

Characteristics of People With and Without a Current Pressure Ulcer (at the Time of the Survey)

Table 5.

Adjusted Odds Ratios and 95% CIs for a Current Pressure Ulcer (at the Time of the Survey)

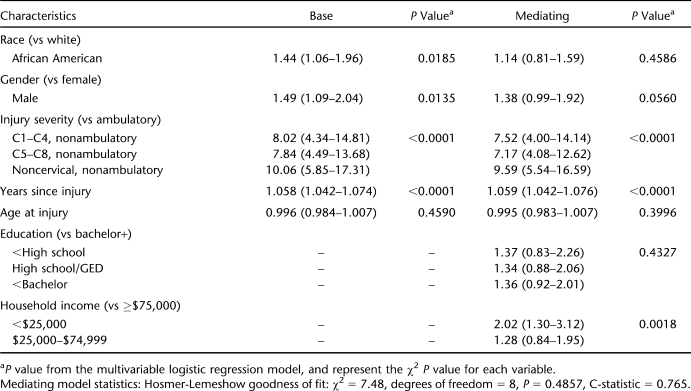

Pressure Ulcer Surgery Since SCI Onset

In the univariate analysis, race was significant, with African Americans being more likely to have ever had a surgery for a PrU than whites (Table 6). Education and household income were also significant, with those with less education and those with less income being more likely to have had a surgery for a PrU since injury.

Table 6.

Characteristics of People Who Had and Who Never Had Surgery for a Pressure Ulcer Since Their Injury

Race remained significant in the base model while controlling for biographic and injury characteristics but was nonsignificant in the mediating model that included education and household income (Table 7). In that model, education also was nonsignificant, but low income was associated with increased odds of having had a surgery for a PrU since injury. Similar to the previous model, having more years since injury was associated with surgery for a PrU, as was being nonambulatory.

Table 7.

Adjusted Odds Ratios and 95% CIs for People Who Had Surgery for a Pressure Ulcer Since Their Injury

DISCUSSION

Our findings generally confirm previous research that identified a significantly higher risk of PrU as a function of race, although the findings were not unequivocal. Previously, Chen and associates (7) found African Americans to be at increased risk for stage II or greater PrUs after controlling for education level, and Saladin and Krause (5) found racial/ethnic differences between African Americans and Hispanics and between American Indians and Hispanics (they did not directly compare African Americans and whites, and Hispanics were the referent group). Also, race was a significant predictor of 2 of 3 PrU outcomes, including a current PrU and the history of at least one surgical intervention for people. In each case, African American participants were at greater risk than white participants.

We also tested mediational models for each outcome to identify whether 2 aspects of SES, education and household income, mediate any observed relationships between race and PrU. For mediation to be demonstrated, there must be a significant relationship between the primary variable, in this case race, and each of the PrU outcome measures. Because only 2 of 3 PrU outcomes were significantly related to race, mediation was only possible for a current PrU and a history of surgical intervention for PrU. The second condition for mediation, that the mediators were related to race, was met in each of the 3 analyses. The final and most important test of mediation is whether the initial relationship between the predictor and outcome (ie, race and PrU) is no longer significant after introduction of the mediators. This was true in each instance. Therefore, we can say that mediation occurred for 2 of the 3 outcomes (current PrU and surgical intervention for PrU). It is interesting to note that “years of education” was not statistically significant after introduction of household income for having had surgery for a PrU.

This study provides new information on the relationship between SES and PrUs through the inclusion of income as a predictor variable. Although one study out of Canada found no relationship between income and PrUs, it is difficult to draw conclusions from that study and apply them to the US population, because the health care systems between the 2 countries are vastly different (22). Our results highlight the importance of income in relation to PrUs after SCI, and although it does provide a measurement of financial revenue, income is also an important predictor because it is associated with health insurance (23) and with access to health care (24). These findings are not surprising given the importance of income in relation to mortality among people with SCI (1). However, education was only related to having a current PrU, and race was not associated with any of the PrU outcomes after controlling for other variables in the model.

These findings strongly suggest it is tangible income, not education per se, that is associated with risk of PrU and the mediational relationship between race, SES, and PrU. The findings also suggest that the association of race with lower SES, particularly lower income, accounts for observed differences in PrU after SCI onset. This is fully consistent with results of previous research indicating similar mediational effects of SES on the relationship between race and depressive symptoms among African American men (25). Interestingly, in that study, the mediational effects were complete only for men, although partial mediation was observed for women. Income was also more important than education in that study.

Limitations

Our study had 5 primary limitations. First, our data were self-reported and therefore could be subject to recall bias. However, most of our questions were limited in scope to the previous year to minimize recall bias. Second, because our data were self-reported, we were not able to assess the severity of reported PrUs but were limited to a more general assessment of the occurrence of an event (yes or no). Although we limited our assessment to open PrUs, it is possible that individuals reported all PrUs (even those not open) in their survey. Third, we were not able to include races other than white and African American due to the limited number of participants from other races. Fourth, these data were cross-sectional, so we were not able to assess the sequence of events for the variables measured. Lastly, we were limited in our measurement of SES, in that we included only education and household income.

Future Research

Future work is needed to gain a better understanding of the nature of the relationship between SES and PrUs. Future studies should expand on the measurement of SES and include more specific variables on access to health care and the use of health care services in relation to PrU outcomes. Further research should include additional race and ethnic groups in the analysis. Future studies should assess the knowledge of PrUs and PrU prevention among the different race and SES groups.

CONCLUSION

Our findings have helped to clarify the relationships between race and SES with PrUs after SCI. Specifically, a lack of resources, both financial and educational, is associated with worse PrU outcomes. The results of this study can be used by both providers and policy makers when considering prevention and intervention strategies for PrUs among people with SCI.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following people whose contributions made completion of this article possible: Richard Aust, Jennifer Coker, Philip Edles, Kristian Manley, Sean Twohig, and Yusheng Zhai, Sarah Lottes, and Christina McCleery of the Shepherd Center.

Footnotes

The contents of this publication were developed under grants from the Department of Education, #H133A080064 and #H133G050165 from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, and supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health grant #1R01NS48117. However, the contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and endorsement by the US government should not be assumed.

References

- Krause JS, Zhai Y, Saunders LL, Carter RE. Risk of mortality after spinal cord injury: an 8-year prospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(10):1708–1715. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RL, Gerhart KA, McCray J, Menconi JC, Whiteneck GG. Secondary conditions following spinal cord injury in a population-based sample. Spinal Cord. 1998;36(1):45–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelis A, Dupeyron A, Legros P, Benaim C, Pelissier J, Fattal C. Pressure ulcer risk factors in persons with SCI: part I: acute and rehabilitation stages. Spinal Cord. 2009;47(2):99–107. doi: 10.1038/sc.2008.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelis A, Dupeyron A, Legros P, Benaim C, Pelissier J, Fattal C. Pressure ulcer risk factors in persons with spinal cord injury: part 2: the chronic stage. Spinal Cord. 2009;47(9):651–661. doi: 10.1038/sc.2009.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saladin LS, Krause JS, Adkins RH. Pressure ulcer prevalence and barriers to treatment after spinal cord injury: comparisons of 4 groups based on race-ethnicity. NeuroRehabilitation. 2009;24(1):57–66. doi: 10.3233/NRE-2009-0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guihan M, Garber SL, Bombardier CH, Goldstein B, Holmes SA, Cao L. Predictors of pressure ulcer recurrence in veterans with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2008;31(5):551–559. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2008.11754570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Devivo MJ, Jackson AB. Pressure ulcer prevalence in people with spinal cord injury: age-period-duration effects. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(6):1208–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redelings MD, Lee NE, Sorvillo F. Pressure ulcers: more lethal than we thought. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2005;18(7):367–372. doi: 10.1097/00129334-200509000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrer MJ, Garber SL, Rintala DH, Clearman R, Hart KA. Pressure ulcers in community-resident persons with spinal cord injury: prevalence and risk factors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74(11):1172–1177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barczak CA, Barnett RI, Childs EJ, Bosley LM. Fourth national pressure ulcer prevalence survey. Adv Wound Care. 1997;10(4):18–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlung SR, Miller WL, Bosley LM. The 1999 National Pressure Ulcer Prevalence Survey: a benchmarking approach. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2001;14(6):297–301. doi: 10.1097/00129334-200111000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer MM, Ferraro KF. Are racial disparities in health conditional on socioeconomic status. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(1):191–204. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause JS, Broderick LE, Saladin LK, Broyles J. Racial disparities in health outcomes after spinal injury: mediating effects of education and income. J Spinal Cord Med. 2006;29(1):17–25. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2006.11753852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause JS, Broderick LE. Outcomes after spinal cord injury: comparisons as a function of gender and race ethnicity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(3):355–362. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00615-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella K, Williams DR. Health disparities based on socioeconomic inequities: implications for urban health care. Acad Med. 2004;79(12):1139–1147. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200412000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause JS, Reed KS, McArdle JJ. A structural anlaysis of health outcomes after spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2010;33(1):22–32. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2010.11689671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MA. Report of the task force on the implications for darkly pigmented intact skin in the prediction and prevention of pressure ulcers. Adv Wound Care. 1995;8(6):34–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause JS, Broderick L. Patterns of recurrent pressure ulcers after spinal cord injury: identification of risk and protective factors 5 or more years after onset. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(8):1257–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.08.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause JS, Carter RE, Pickelsimer E, Wilson D. A prospective study of health and risk of mortality after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(8):1482–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.11.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Noreau L, Proulx P, Gagnon L, Drolet M, Laramee MT. Secondary impairments after spinal cord injury: a population-based study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;79(6):526–535. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200011000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L. The convergence of vulnerable characteristics and health insurance in the US. Soc Sci Med (1982) 2001;53(4):519–529. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00357-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleis JR, Lucas JW. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2007. Vital Health Stat 10. 2009. pp. 1–159. [PubMed]

- Krause JS, Kemp B, Coker JL. Depression after spinal cord injury: relation to gender, ethnicity, aging, and socioeconomic indicators. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(8):1099–1109. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2000.7167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]