Abstract

Integrin αvβ6 is a heterodimeric cell surface receptor which is absent from normal epithelium, but expressed in wound-edge keratinocytes during re-epithelialization. However, the function of the αvβ6 integrin in wound repair remains unclear. Impaired wound healing in patients with diabetes constitutes a major clinical problem worldwide and has been associated with accumulation of advanced glycated endproducts (AGEs) in the tissues. AGEs may account for aberrant interactions between integrin receptors and their extracellular matrix ligands such as fibronectin (FN). In this study, we compared healing of experimental excisional skin wounds in wild-type (WT) and β6-knockout (β6-/-) mice with streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetes. Results showed that diabetic β6-/- mice had significant delay in early wound closure rate as compared to diabetic WT mice, suggesting that the αvβ6 integrin may serve as a protective role in re-epithelialization of diabetic wounds.

To mimic glycosylated wound matrix, we generated a methylglyoxal (MG)-glycated variant of FN. Keratinocytes utilized αvβ6 and ß1 integrins for spreading on both nonglycated and MG-FN, but their spreading was reduced on MG-FN. These findings indicated that glycation of FN and possibly other integrin ligands could hamper keratinocyte interactions with the provisional matrix proteins during re-epithelialization of diabetic wounds.

Keywords: Wound healing, integrins, fibronectin (FN), diabetes mellitus, advanced glycated endproducts (AGEs)

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus affects approximately 170 million people world wide, and this number is projected to double by the year 2030 (1). Diabetes has been associated with a number of physiological factors that predispose to aberrant wound healing, such as impaired growth factor production (2-4), angiogenic response (4,5), macrophage function (6), collagen accumulation, epidermal barrier function, quantity of granulation tissue (4), keratinocyte and fibroblast migration and proliferation (7), synthesis of ECM components and their remodelling by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (8). In addition, a prolonged state of systemic hyperglycemia is an important factor for the molecular pathophysiology of diabetic complications due to the gradual build-up of advanced glycated endproducts (AGEs) in the tissues. AGEs are formed by an irreversibly, non-enzymatic reaction between the amino groups of tissue proteins, such as collagen and FN in the extracellular matrix (ECM), and reducing sugars, which are abundant in hyperglycemia (9). These modifications of the ECM proteins alter cell-ECM interactions, including cell adhesion and migration that are critical for wound healing (9). It is likely that the changes are mediated by aberrant interactions of the glycated ECM proteins with the cell surface receptors of the integrin family.

Integrins are heterodimeric, transmembrane receptors that consist of an α and a β subunit (10-12). Through specific interactions with ECM proteins, integrins mediate cell adhesion and migration, proliferation and survival of many cell types, including keratinocytes (13,14). During wound healing, keratinocyte integrins regulate wound re-epithelialization (14,15). Many integrins recognize a specific conserved tri-peptide motif, arginine-glycine-asparagine (RGD) which is found in a variety of ECM proteins such as FN, vitronectin and tenascin-C (16,17). In cell culture, the expression of keratinocyte-specific αvβ6 integrin facilitates keratinocyte adhesion and migration on the early wound provisional matrix (18,19). Furthermore, the αvβ6 integrin activates TGF-β1, an important molecule that promotes wound re-epithelialization by binding to the latent TGF-β complex (20,21). In fact, αvβ6 integrin may be critically important for TGF-β1 bioactivity in vivo (22). Studies of acute wound healing in young β6 integrin-deficient mice (β6-/-) and β6 integrin over-expressing mice did not detect any abnormalities in the healing of experimental skin wounds (23,24) suggesting that this integrin may not be necessary for normal wound healing. In contrast, in mice where wound healing was compromised by corticosteroid-induced immunosuppression or by old age, β6 integrin deficiency resulted to delayed wound healing (25). In diabetic ulcers, wound closure is delayed or lacking as a result of reduced epithelial migration. In addition, the level of TGF-β in diabetic wounds is reduced compared to non-diabetic wounds (26). Therefore, we hypothesized that αvβ6 integrin plays a role in compromised wound healing associated with the diabetic state. To this end, we examined the role of αvβ6 integrin in wound healing in adult mice in which diabetes was induced by intraperitoneal injections of streptozotocin (STZ). Furthermore, we investigated the effects of glycation of the provisional wound matrix protein FN on integrin-mediated adhesion of human skin keratinocytes.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The animal studies were conducted in compliance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care (CACC) and approved by the University of British Columbia Animal Care Committee. Forty-eight 12 to 14-months-old male wild type (WT) FVB and age and sex-matched β6-/- mice with the same genetic background were used in this study (generous gift from Dr. Dean Sheppard, University of California, San Francisco). Each experimental group was subdivided into streptozotocin (STZ)-treated (WT: n=14, β6-/-: n=15) and untreated control groups (WT: n=9, β6-/-: n=10).

Streptozotocin induction of diabetes in mice

Mice were maintained under fasting conditions for 4 hours and subsequently anaesthetised with a mixture of isoflurane and oxygen. Following induction of anaesthesia, mice in the experimental group received peritoneal injections of STZ (55 mg/kg of body weight; Sigma Aldrich Inc., St. Louis, MO) in citrate buffer (P-4809, Sigma Aldrich Inc.). Animals in the control group were injected with an equivalent volume of citrate buffer only. This treatment was carried out for six consecutive days. Tail blood samples were collected weekly basis from fasting animals and analysed for serum glucose level using the Accu-chek® system (Roche Diagnostics, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland) to verify successful development of experimental diabetes in the STZ-treated animals. A serum glucose concentration exceeding 17 mmol/L was considered to reflect onset of diabetes (27,28).

Experimental wounds

Animals were anaesthetised as described above, and the dorsal skin was shaved and depilated (Veet™, Reckitt-Benckiser, NA Inc., Parsippany, NJ). Four full-thickness, 4 mm excisional wounds were created on the dorsal skin of each mouse using a sterile, disposable biopsy punch (Miltex, Inc., York, PA). After wounding, mice were maintained in separate cages and had access to food and water ad libitum. To assess the rate of wound healing, images of all wounds were recorded at the time of wounding (day 0) and on a daily basis post-wounding using a digital camera (Nikon Coolpix 995, Tokyo, Japan). All wound pictures were standardized according to a measurement ruler included in the images. The wound surface areas were quantified using the NIH ImageJ program (National Institute of Health; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/), and the healing was expressed as a percentage of the initial wound area on day 0. A total of n=36-56 wounds per group were analyzed from each time point.

Histological and immunohistochemical examination of wounds

For histological and immunohistochemical analyses, tissue biopsies were obtained from the wound sites on days 5 and 10 after wounding. To this end, mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation and wound biopsies containing the complete wounded area as well as adjacent wound margin and normal skin were harvested using a 6 mm sterile biopsy punch. The tissue samples were mounted in Tissue-TEK (Sakura, Torrance, CA) and snap-frozen on dry ice immediately following collection. Frozen sections (6 μm) were prepared and stored at -80°C until use. For orientation and to localize mid-wound sections, every tenth slide was stained with Harris' hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Only the mid-wound sections were used for comparative analyses. Epithelial gap distance was measured as the distance between epithelial tongues in the wound cross sections using NIH ImageJ, and histology was scored from 1 (lowest) to 4 (highest) based on previously used criteria (29). A subset of 5-day-old wounds were fixed with 10% buffered neutral formalin and stained using a modified Movat's pentachrome staining procedure. Briefly, the fixed sections were placed in Alcian blue dye over night and rinsed in running water for 5 min. The sections were then soaked in warm (60°C) alkaline alcohol for 60 min, followed by the standard staining procedure as described previously (30). Histological assessment of granulation tissue formation used an ordinate scale from 1 to 4 reflecting the degree of density and organization of neo-synthesized collagen fibre bundles as low (1), medium (2), or high (3). Presence of mature collagen among well-granulated wounds yielded a score of 4. All histological scoring was done in a blinded manner, evaluating n=5-6 wounds (two sections per wound) from 5-6 mice per group.

For detection of the αvβ6 integrins in experimental and control wounds, frozen sections were fixed for 5 min with acetone pre-cooled to -20 °C, rinsed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS; 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCL, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4 in distilled water, pH 7.4) containing 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma Aldrich Inc.), and incubated with normal blocking serum (Vectastain, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) at room temperature for 30 min. For detection of the αvβ6 integrin, sections were incubated with rabbit anti-human monoclonal antibody β6B1 (a generous gift from Dr. Dean Sheppard, University of California, San Francisco, CA) diluted 1:10 dilution in PBS containing 1 mg/ml BSA in a humidified chamber at 4 °C over night. After washing with PBS/BSA, sections were first incubated with an anti-rabbit biotinylated secondary antibody for 60 min at room temperature, and then with Vectastain® ABC reagent (Vectastain® Elite Kit) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. The reaction was visualized using the VIP (purple stain) substrate kit. Primary antibody was omitted in the negative controls, none of which showed positive staining.

Glycation of fibronectin with methylglyoxal

FN was purified from human plasma by gelatin-Sepharose affinity chromatography according to established procedures (31). Briefly, plasma was diluted in chromatography buffer (50 mM Tris; 0.15 M NaCl, pH 7.4) and particulate matter was sedimented by centrifugation at 2,500 × g for 20 min. The supernatant was loaded on a gelatine-Sepharose affinity column (GE Healthcare Bio-sciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden). After extensive washes with chromatography buffer alone, non-specifically-bound proteins were removed with buffer containing 1 M NaCl. Gelatin binding MMP-2 and MMP-9 were eluted with 2% DMSO and bound FN was eluted with 3 M urea in chromatography buffer (32). Elimination of MMP-2 and -9 was verified by gelatine enzymography using 10% SDS-PAGE gels copolymerized with heat-denatured type I collagen (33,34). Purified FN was quantified by the BCA assay (Pierce, Rockford, Illinois, USA), frozen slowly, and stored at -80 °C until analysis.

For glycation, purified human FN (866 μg/ml) was incubated with 67 mM methylglyoxal (MG; Sigma chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) at a 1:83 molar ratio (FN:MG) in PBS. Non-treated FN control was diluted to the same concentration in PBS without MG and dialyzed against PBS for the same periods of time (9). To confirm the conjugation of MG to FN molecules, an affinity-purified rabbit anti-MG-AGE polyclonal antibody (kindly provided by Dr. Shamsi, University of Cleveland, OH) (35) was used as a probe. Glycated FN, as well as untreated control samples were separated with 7.5% SDS-PAGE gels under reducing conditions (65 mM dithiothreitol) and then transferred to polyvinylidene diflouride membranes (Milipore Corp., Bedford, MA). The membranes were blocked with 10 mg/ml heat-denatured BSA in 50 mM tris, pH 7.4 at 37 °C for 60 min, and then incubated with rabbit anti-MG-AGE at a 1:2,000 dilution in 20 mM Tris/150 mM NaCl/0.1% Tween 20 buffer (pH 7.4) containing with 1% (w/v) BSA at 4 °C overnight. MG treated protein was detected with a horseradish peroxidise-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (IgG H+L) at a 1:5,000 dilution in PBS/Tween containing 5 mg/ml BSA, followed by chemiluminescence reagent (PerkinElmer LAS, Inc. Boston, MA) for 1 min. The image was captured using the ChemiDoc XRS Imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Plate binding assay for coating efficiency

To determine whether FN and FN-MG were coated with the same efficiency, the proteins were incubated in 96-well plates at identical, serially diluted concentrations from 2 to 0.002 μg/well in 0.1 M NaHCO3/Na2CO3 (pH 9.6) at 4°C overnight. Heat denatured BSA (10 mg/ml) in 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4) was used to block non-specific binding sites for 1 hour at 22°C. After thorough washing with 50 mM Tris buffer containing 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20, plates were incubated with a polyclonal rabbit anti-FN antibody (36) for 60 min at 22°C. Bound proteins were detected using alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:1,000 dilution; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) for 1 hour at 22°C. After several rinses, 1 mg/ml phosphatase substrate (Sigma Aldrich Inc.) was added to the wells. The reactions were quantified at 405 nm with an Opsys MR plate reader (Dynes, Chantilly, VA, USA).

Cell spreading assay

A 48-well culture plate (Falcon Multiwell™, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) was coated with 5, 20, or 50 μg/ml FN or FN-MG diluted in PBS containing Ca2+ and Mg2+ for 1 hour at room temperature. Wells were then blocked with 1% heat-denatured BSA in PBS for 30 min at room temperature and subsequently washed twice in PBS. Sub-confluent human skin HaCaT keratinocytes (a generous gift from Dr. Fusenig, German Cancer Center, Heidelberg, Germany) were seeded at 2.0 × 104 cells per well in serum free Dulbecco's Modified Eagles Medium (DMEM, Flow laboratories, Irvine, UK) supplemented with 23 mM Na2CO3, 20 mM Hepes (Gibco™, Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA), antibiotics (50 μg/ml streptomycin sulphate and 100 U/ml penicillin, Sigma Aldrich, Inc.), 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum, (FBS; Gibco Life Technologies), and 50 μM cycloheximide (Sigma Aldrich, Inc.) to prevent de novo protein synthesis. Cells were incubated for 45 min to 3h at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2 to allow cell spreading. At indicated time points, the experiment was terminated by the addition of appropriate volume of 2× cell fixative (8% formaldehyde, 10% sucrose in PBS). The wells were then filled with distilled water to the top and covered with a glass plate for analysis. Cells with a ring of lamellar cytoplasm were considered spread. Cell spreading was quantified using a phase-contrast microscope (Nikon TMS, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a grid-eyepiece as detailed previously (19). Briefly, the number of cells showing spreading in four randomly selected fields from each of three replicate wells was counted, and cells that were surrounded by a ring of lamellar cytoplasm were considered spread.

Blocking of integrin function

Cells were seeded at 1.0×104 cells per well in 96-well plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) coated with FN or FN-MG as in the presence or absence of monoclonal antibodies with the capacity to speficially block the functions of the β1 (mAb13; 20 μg/ml; (37)), αv (L230; 20 μg/ml), or β6 (10D5; 50 μg/ml; (38)) integrin subunits. Antibody L230 was purified from culture supernatants of hybridoma cells (ATCC HB8448) in our laboratory. All antibody concentrations used were previously optimized to produce maximal inhibition of cell spreading (data not shown). The cells were incubated with the anti-integrin antibodies for 15 min on ice prior to seeding and transfer to the cell culture incubator (5% CO2; 37 °C) for cell adhesion and spreading. When about 50% of cells without inhibitory antibodies showed spreading, all cells were fixed and cell spreading quantified.

Statistical analysis

A Student's t-test (two-tailed, Bonferroni-adjusted) was used to assess pairwise differences in wound healing kinetics between each day of healing, whereas epithelial gap distances from mid-wound H&E sections were analyzed using a Mann-Whitney U-test (GraphPad Prism 5.0, GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). For all cell spreading experiments we used a two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's post-test to describe differences between cell behaviour on native vs. glycated FN for various concentrations of FN, time, and anti-integrin antibody blockings. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

STZ-induction of experimental diabetes

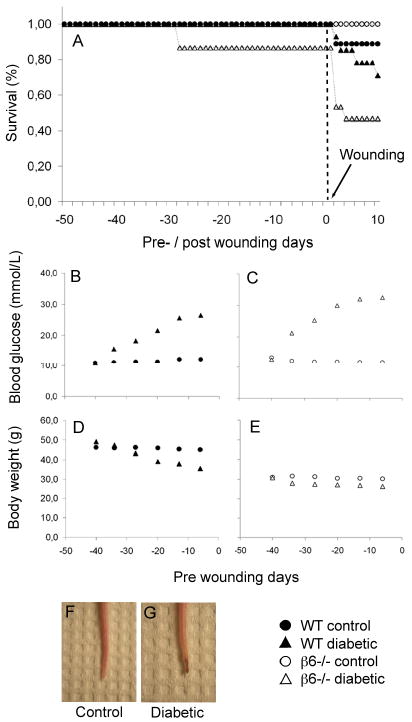

For six consecutive days beginning on day 50 prior to generating experimental wounds, adult FVB WT and β6 integrin knockout mice were treated intraperitoneally with STZ to induce pancreatic β-cell autoimmunity and a chronic state of systemic hyperglycemia. During these 50 days, we observed an insignificant loss of animals in the control group, but considerable losses among the diabetic animals, especially in the β6-/- group (Fig. 1A). Blood glucose measurements (Fig. 1B and C), each time taken after four hours of fasting, showed that a glucose concentration above 17 mmol/l reflecting a diabetic state (27) was achieved within the first two weeks of STZ treatment for both FVB and β6-/- mice. A steady state of severe hyperglycemia (25-30 mmol/l) developed approximately 10 days prior to wounding in STZ-treated animals, whereas all control mice maintained normal blood glucose levels of 10-11 mmol/l throughout the study period. Body weights (Fig. 1D and E) decreased only in the diabetic populations, a clinical sign of impaired glucose uptake. Mice in the β6-/- group had lower body weights compared to their FVB WT littermates. Tail neuropathy was consistent with a state of chronic hyperclycemia (Fig. 1F and G).

Fig. 1.

(A) Survival data for 50 days pre-wounding and 10 days post-wounding period of wild type (WT; n=9, control; n=14, diabetic) and β6-/- (n=10, control; n=15, diabetic) mice. (B) Blood glucose levels for WT control vs. diabetic animals and (C) for β6-/- control vs. β6-/- diabetic animals. (D) Mean body weight for control vs. diabetic animals and (E) for β6-/- control vs. β6-/- diabetic animals. (F) Representative images of mouse tails from the untreated control group compared with streptozotocin-induced diabetes group (G) displaying clinical signs of neuropathy.

Wound healing kinetics

To evaluate the contribution of the β6 integrin to wound repair in normal and diabetic mice, we first quantified clinical wound healing from digitized images. A representative panel is shown from day 0, 5, and 10 from all four experimental groups (Fig. 2A). The final sample consisted of 36-56 wounds per experimental group. Changes in size of wound areas are presented in Fig. 2B-F. Wounds in the control groups were closed by day 7 with no difference in healing rates between the WT and ß6-/- mice (Fig. 2B). In comparison, among the diabetic animals, ß6-/- mice showed a small but significant delay in wound healing from day 1 to 3 compared to WT, but no other differences were observed and complete wound closure was reached on day 9 (Fig. 2C). Induction of diabetes in the WT animals caused a small, but significant delay in wound healing on days 3 and 4 (p< 0.05), and the wounds closed at the same time as WT animals without diabetes (Fig. 2D). Finally, the diabetic β6-/- mice exhibited approximately a whole day delay in wound healing compared to β6-/- mice without diabetes. The difference was statistically significant from day 1 to 6 (Fig. 2E). The combined effects of the β6 knockout and the diabetic state resulted in an overall delay in wound closure of nearly two days compared to the WT mice (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

(A) Representative clinical photographs of excisional wounds from WT and β6-/- mice treated with citrate buffer only (control) or 55mg/kg streptozotocin in citrate buffer (diabetic) at day 0, 5 and 10 after wounding. Wound closure rate in the control mice was similar compared to WT and β6-/- mice, whereas a delay in wound closure could be observed for the diabetic WT and especially the diabetic β6-/- mice. Scale bar: 10 mm. (B-F) Relative wound area change over time. Data show mean ± sem percent of wound area relative to wound size at day 0 within each group (n=36-56 wounds per group). Statistical significance between the two groups at each time point was assessed by Student's t-test, * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

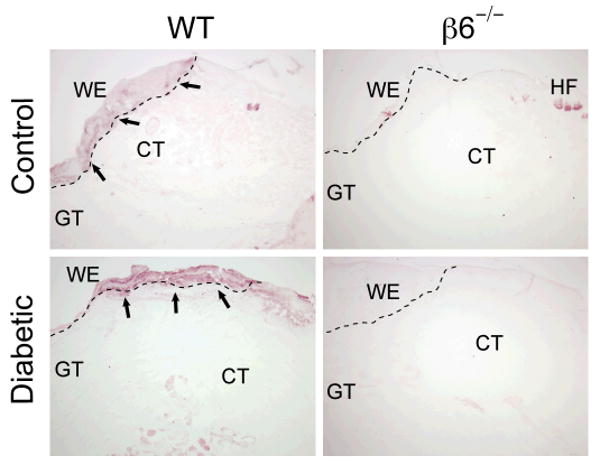

Histological staining of 5-day-old wound specimens (Fig. 3A) confirmed the clinical wound-healing data with a significant difference in epithelial gap distance between control- and diabetic animals (p<0.01). Deficiency of β6-integrin did not lead to increased epithelial gap distance in normal wound repair (p=0.578), but was more influential in diabetic wound healing, yet statistically insignificant at day 5 (p=0.112) (Fig 3B). In concordance with these observations, histological scoring at day 5 showed no difference among the control animals, but a reduced score for the diabetic animals, and in particular the group deficient of the β6-integrin (Fig. 3C). The Movat's modified pentachrome staining was carried out on a set of day 5 wounds to assess the formation of granulation tissue and collagen deposition (Fig. 4A). The wounds in the control animals revealed more mature collagen (yellow) at the connective tissue sites than in the diabetic wounds, where neo-synthesized collagen (light bluish-green) seemed to dominate, indicating delayed wound healing. Histological scoring revealed a tendency towards reduced formation of granulation tissue among the diabetic animals, especially in the β6-/- mice, but statistical significance could not be achieved (Fig. 4B). As a control experiment, we localized the presence/absence of the αvβ6 integrin at the wound edge sites by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 5). The keratinocytes at the wound edges of WT animals stained positive for the αvβ6 integrin in both untreated and STZ-treated mice. The β6-/- mice all stained negative apart from some background staining of hair follicles in the unwounded normal skin.

Fig. 3.

(A) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of day 5 mid-wound sections from WT and β6-/- mice treated with citrate-buffer (control) and 55mg/kg streptozotocin in citrate buffer (diabetic). E, epithelium; GT, granulation tissue; CT, connective tissue; WC, wound crust. Dashed lines indicate epithelial gap distance. Scale bar: 1mm. (B) Epithelial gap distances were measured from day 5 mid-wound H&E sections as the distance between epithelial tongues from all four groups. Mann-Whitney's U-test revealed overall significant differences between control and diabetc animals (p<0.01), and also between diabetic WT and β6-/- mice, respectively (p<0.05). (C) Histology was scored from 1 (lowest) to 4 (highest) based on the degree of cellular invasion, GT formation, vascularity, and re-epithelialization. n=10-12 sections (two ections per wound) from 5-6 mice per group. Scale bars in B and C show mean ± s.d, * p<0.05, ** p<0.01.

Fig. 4.

(A) Movat's modified pentachrome staining of representative day 5 mid-wound sections from WT and β6-/- mice treated with citrate-buffered (control) and 55mg/kg citrate-buffered streptozotocin (STZ, diabetic). Control animals (WT and β6-/-) show similar dense and well-organized neo-synthesized collagen fibre bundles (blue-green) in the granulation tissue (GT) Small amounts of mature collagen (yellow) appear near the epidermis (E) and at the wound edge (WE) proximal to the unwounded connective tissue (arrows) and clarified by magnified picture insets. STZ-treated diabetic mice show less formation of GT, especially in the case of the β6-/- group, and no mature collagen is observed in either WT or β6-/- mice. Scale bars: 100 μm.

(B) The degree of GT formation from 5-6 mice per group was scored by an ordinate scale (1 to 4) according to the degree of density and organization of neo-synthesized collagen fibre bundles as low (1), medium (2), or high (3). Presence of mature collagen among well-granulated wounds yielded a score of 4. No statistical difference could be established, but a tendency towards reduced GT formation among the diabetic animals, especially the β6-/- mice, was observed. Bars show mean ± s.d, n=10-12 sections (two sections per wound) from 5-6 wounds.

Fig. 5.

Immunolocalization of β6-integrin in day-5 mid-wound sections from WT and β6-/- mice treated with citrate-buffer (control) and 55mg/kg citrate-buffered streptozotocin (diabetic). β6-/- mice showed a complete lack of β6-integrin staining in all specimens examined, with the exception of limited background staining of hair follicles. In the WT mice, the immunoreactivity of β6 integrin was confined to the wound edge of the epithelium containing populations of proliferating and migrating keratinocytes. WE, wound edge; GT, granulation tissue; CT, connective tissue; HF, hair follicles. Scale bar 200 μm.

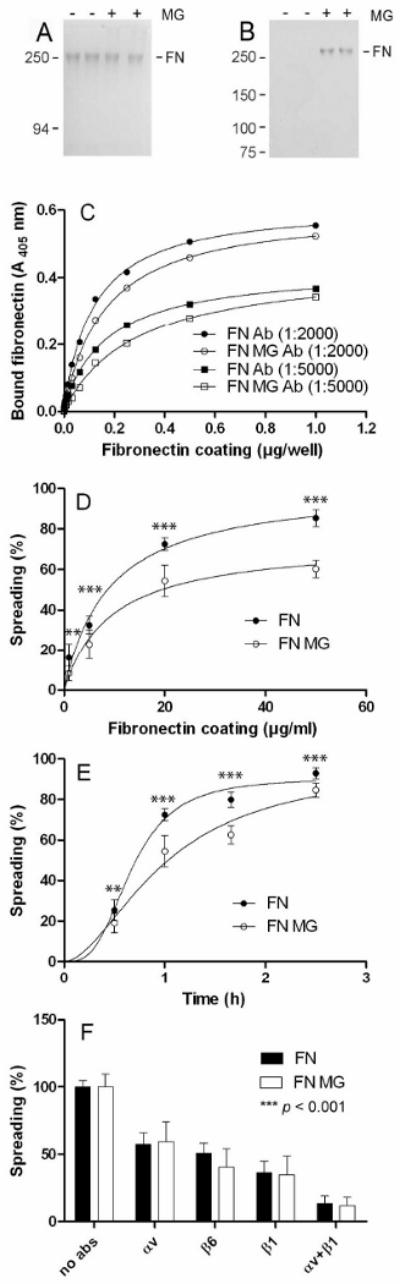

Glycation of FN impairs HaCaT cell spreading in vitro

We hypothesized that the delayed wound re-epithelialization could be associated with aberrant cross-linking to important integrin-binding ligands of the wound bed matrix due to the formation of advanced glycated endproducts (AGEs). Therefore, we performed an in vitro spreading assay using human HaCaT keratinocytes seeded on the integrin-binding ligand FN. For these experiments, we used FN that had been treated with MG to generate advanced glycation endproducts to mimic the diabetes-induced hyperglycaemic effect on ECM tissue proteins.

Gel-electrophoresis and Western blotting were used to verify the glycation of FN occurred by treatment with MG as has been reported in studies by others (9,35). MG-treated (FN-MG) and untreated FN showed similar mobility in SDS-PAGE gels (Fig. 6A), but Western blotting using antibodies with specificity for the methylglyoxal (MG)-conjugated part of the FN-MG protein-sugar complex confirmed the reaction (Fig. 6B). Importantly, glycated and native FN showed similar coating efficiency to ELISA plates used in the subsequent cell experiments (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

(A) Binding affinity of human fibronectin (FN) and the methylglyoxal treated FN (FN-MG). Immunolabelling with specific antibodies (Ab) showed similar binding affinity to the microtiter plate between the two fibronectin-preparations. (B) SDS-PAGE and (C) Western blot using an antibody that recognizes specifically FN-MG. (D) HaCaT keratinocytes were allowed to spread for 1 hour on various concentrations of native fibronectin or FN-MG or (E) on 20 μg/ml fibronectin or FN-MG over time. In both cases, cells showed reduced spreading on FN-MG (○) compared with FN (●) in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. (F) HaCaT spreading was also quantified in the presence of function blocking anti-integrin antibodies targeted against the αv, β1 and β6 subunits. Data shows mean ± sem of three independent experiments, n=4 (D-E) and n=8 (F). The effect of integrin blocking accounted for 88% of the total variation (p<0.001), whereas no statistical difference was observed between keratinocyte spreading on FN and FN-MG within the same anti-integrin antibody blocking. All keratinocyte spreading data (D-F) were evalutated by a two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests, *p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

The spreading-frequency of HaCaT keratinocytes was determined upon seeding the cells on FN versus FN-MG-coated substrates. The spreading of HaCaT cells on FN-MG substrate was significantly reduced as compared to FN substrate (Fig. 6D). On substrates coated with 10 μg/ml of control FN about 50% HaCaT cell showed spreading, whereas twice the coating concentration for FN-MG was necessary to obtain the same spreading frequency (Fig. 6D). In addition, a significantly slower HaCaT cell spreading was observed on FN-MG as compared to FN in time course experiments (Fig. 6E). Next, we investigated whether HaCaT keratinocytes utilized the same integrin receptors for binding FN-MG and FN. Incubation of cells with function blocking antibodies against αv and ß6 integrin subunits caused about 50% inhibition of cell spreading on both FN-MG and FN substrates (Fig. 6F). Likewise, incubation with an antibody against the ß1 integrin subunit caused about 60% inhibition of cell spreading on both substrates, and applying a combination of antibodies to αv and ß1 integrins caused more than 90% inhibition (Fig. 6F). These results indicate that both αv and ß1 integrins can support HaCaT keratinocyte spreading on FN regardless of its glycation state.

Discussion

Diabetes mellitus constitutes a major clinical problem and is associated with many complications, including impaired wound healing. Since re-epithelialization is a crucial step of tissue repair characterised by migrating wound edge keratinocytes over a provisional matrix to restore barrier function, we investigated the role of the putative cell adhesion receptor αvβ6 integrin in epidermal wound healing in a diabetic mouse model. The induction of hyperglycemia in rodents using repeated injections of 55 mg/kg of STZ mimics diabetes mellitus type I that is caused by a T-cell mediated auto-immune reaction against the pancreatic islet β-cells (39,40). This approach results eventually in a chronic stage of hyperglycemia. It is different from the diabetic state caused by a single higher dose (160-250 mg/kg) of STZ, which induces an acute and transient state of diabetes characterised by direct cytotoxicity, DNA damage, and apoptosis among the pancreatic β-cells (41-43). Our observation of an increased frequency of premature deaths among the diabetic β6-knockout mice post wounding may be due to the combination of a chronic hyperglycemia and a mildly exaggerated inflammation in lungs and skin, which is associated with the β6-deficient phenotype (17).

In other diabetic rodent models, wound healing studies are often performed using the leptin receptor-deficient db/db-mouse, which represents a model for type II diabetes mellitus characterized by hyperglycemia, obesity, hyperinsulinemia, and impaired wound healing (44,45). The db/db-mouse is genetically diabetic and thereby negates the need for STZ administration (46). However, as our goal was to specifically assess the role of αvβ6 integrin in diabetic wound healing, we elected to use the well-established model of chemically induced type I diabetes mellitus by intraperitoneal administration of STZ (41) in β6-integrin deficient mice. By this experimental approach, we successfully generated chronic hyperglycemia, which in these animals predisposes to multiple vascular complications and cutaneous dysfunctions such as impaired wound repair due to AGE-formation similar to humans (47).

Our quantitative analysis of clinical wound pictures revealed that the lack of β6 integrin did not cause any significant delay in wound healing among vehicle-treated (citrate buffer; control) mice, which is in accordance with previous studies performed on young and adult, female and male mice of the same genetic backgrounds (23,24). However, in the diabetic mice, we observed a statistically significant delay in wound healing in the β6-/- group from day 1 to 3 post wounding (p<0.05), suggesting that the αvβ6 integrin might play a protective role in the re-epithelialization phase of diabetic wound repair. No histological differences at day 5 post-wounding were found between the non-diabetic WT and β6-/- animals when comparing epithelial wound gaps, granulation tissue formation, and collagen deposition. However, among the diabetic animals we observed a reduction in granulation tissue formation, complete absence of mature collagen deposition and a minor tendency towards reduced keratinocyte migration in the ß6-/- mice. Surprisingly, a recent study reported accelerated wound repair in ß6-integrin deficient mice in a dexamethasone (DEX) impaired wound healing model (48). DEX is a glucocorticoid steroid hormone used as an immuno-suppressive drug with unfortunate side-effects such as skin-atrophy and impaired wound healing caused in part by dysregulation of TGF-β1 (49). Xie et al. observed increased proliferation of epidermal and hair follicle-associated keratinocytes in the DEX-treated β6-/- mice compared to DEX-treated WT animals, which was linked to a reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines and TGF-β1 (48). In the STZ-induced diabetes-model the delay in wound healing was mainly associated with initial epithelial migration to the wounds, rather than later stages of reepithelialization that are more dependent on keratinocyte proliferation. Therefore, the re-epithelialization defect observed in STZ-treated β6-/- mice compared to WT diabetic mice is most likely due to keratinocyte migration impairment rather that proliferation as supported by reduced spreading on glycated FN.

As previously described, a prolonged state of hyperglycemia can lead to tissue damage through aberrant cross-linking of proteins in the extracellular matrix and their receptors due to the accumulation of advanced glycated endproducts (AGEs) (50), which can potentially lead to impaired keratinocyte function during re-epithelialization. In this study, we generated glycated FN through reaction with methylglyoxal, a reactive α-oxaloaldehyde derived from the glucose metabolism and one of the most potent AGE-formers found in vitro (51) and in vivo (35). Indeed, intraperitoneal administration of MG results to induced diabetes-like microvascular alterations and impaired wound healing in rats (52), and MG-glycation of provisional matrix constituent type I collagen inhibits keratinocyte migration and spreading, possibly through modification of the putative binding site of integrin α2β1 (53,54). We here demonstrated that keratinocyte spreading was significantly reduced in a time and dose-dependent manner on MG-glycated FN.

Functional inhibition of integrin receptors using specific blocking antibodies demonstrated that the utilization of integrin receptors that bind native FN was not changed by glycation of FN suggesting that the reduced spreading on MG-glycated FN was caused by masking of the integrin binding sites. Intriguingly, AGE-modification of FN alters the putative tripeptide binding site (arginine-glycine-aspartic acid, RGD) which is a ligand for a variety of integrins, including the αvβ6 (18,55). It is possible, therefore, that AGE-induced alteration of the RGD sequence in FN may cause aberrant cross-linking to many potential integrin-receptors, and thereby hamper keratinocyte function during the re-epithelialization phase of diabetic wound healing. Taken together, our data point to a protective role for the αvβ6 integrin in early diabetic wound healing during the phase of re-epithelialization. Moreover, we have demonstrated reduced spreading frequency of human keratinocytes on glycated FN, which could play a role in diabetic wound repair.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Chrisitan Sperantia for excellent technical assistance. Yanshuang Xie, Leeni Koivisto, and Gethin Owen are acknowledged for their kind help on mouse surgery, in vitro experiments and immunolabelling, respectively. We also thank Zhihua Chen for support with purification and biochemical modification of FN. This work was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) to HL, the Tech Transfer Unit at the University of Copenhagen to KAK (274-05-0435), and National Institute of Health (NIH) grants DE017139 and DE016312 to BS. JNJ acknowledges Memorial scholarship of E. and C. Elmquist, The Oticon fund, A.V. Lykfeldt's fund, the Beckett fund, T. and A. Frimodt's fund, C. and O. Brorsons travel grant, and C.M./M.C. Sørensen and Mrs. S.F. Lerchel fund for generous financial support.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1047–53. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goren I, Muller E, Pfeilschifter J, Frank S. Severely impaired insulin signaling in chronic wounds of diabetic ob/ob mice: a potential role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:765–77. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galkowska H, Wojewodzka U, Olszewski WL. Chemokines, cytokines, and growth factors in keratinocytes and dermal endothelial cells in the margin of chronic diabetic foot ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2006;14:558–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falanga V. Wound healing and its impairment in the diabetic foot. Lancet. 2005;366:1736–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67700-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galiano RD, Tepper OM, Pelo CR, Bhatt KA, Callaghan M, Bastidas N, Bunting S, Steinmetz HG, Gurtner GC. Topical vascular endothelial growth factor accelerates diabetic wound healing through increased angiogenesis and by mobilizing and recruiting bone marrow-derived cells. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1935–47. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63754-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maruyama K, Asai J, Ii M, Thorne T, Losordo DW, D'Amore PA. Decreased macrophage number and activation lead to reduced lymphatic vessel formation and contribute to impaired diabetic wound healing. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1178–91. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibran NS, Jang YC, Isik FF, Greenhalgh DG, Muffley LA, Underwood RA, Usui ML, Larsen J, Smith DG, Bunnett N, Ansel JC, Olerud JE. Diminished neuropeptide levels contribute to the impaired cutaneous healing response associated with diabetes mellitus. J Surg Res. 2002;108:122–8. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2002.6525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lobmann R, Ambrosch A, Schultz G, Waldmann K, Schiweck S, Lehnert H. Expression of matrix-metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in the wounds of diabetic and non-diabetic patients. Diabetologia. 2002;45:1011–6. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0868-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murillo J, Wang Y, Xu X, Klebe RJ, Chen Z, Zardeneta G, Pal S, Mikhailova M, Steffensen B. Advanced glycation of type I collagen and fibronectin modifies periodontal cell behavior. J Periodontol. 2008;79:2190–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.080210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stupack DG. Integrins as a distinct subtype of dependence receptors. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:1021–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Arcangelis A, Georges-Labouesse E. Integrin and ECM functions: roles in vertebrate development. Trends Genet. 2000;16:389–95. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–87. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larjava H, Salo T, Haapasalmi K, Kramer RH, Heino J. Expression of integrins and basement membrane components by wound keratinocytes. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:1425–35. doi: 10.1172/JCI116719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santoro MM, Gaudino G. Cellular and molecular facets of keratinocyte reepithelization during wound healing. Exp Cell Res. 2005;304:274–86. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark EA, Brugge JS. Integrins and signal transduction pathways: the road taken. Science. 1995;268:233–9. doi: 10.1126/science.7716514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu M, Munger JS, Steadele M, Busald C, Tellier M, Schnapp LM. Integrin alpha8beta1 mediates adhesion to LAP-TGFbeta1. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:4641–8. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munger JS, Huang X, Kawakatsu H, Griffiths MJ, Dalton SL, Wu J, Pittet JF, Kaminski N, Garat C, Matthay MA, Rifkin DB, Sheppard D. The integrin alpha v beta 6 binds and activates latent TGF beta 1: a mechanism for regulating pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. Cell. 1999;96:319–28. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80545-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Busk M, Pytela R, Sheppard D. Characterization of the integrin alpha v beta 6 as a fibronectin-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:5790–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koivisto L, Larjava K, Hakkinen L, Uitto VJ, Heino J, Larjava H. Different integrins mediate cell spreading, haptotaxis and lateral migration of HaCaT keratinocytes on fibronectin. Cell Adhes Commun. 1999;7:245–57. doi: 10.3109/15419069909010806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Annes JP, Munger JS, Rifkin DB. Making sense of latent TGFbeta activation. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:217–24. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Annes JP, Chen Y, Munger JS, Rifkin DB. Integrin alphaVbeta6-mediated activation of latent TGF-beta requires the latent TGF-beta binding protein-1. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:723–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aluwihare P, Mu Z, Zhao Z, Yu D, Weinreb PH, Horan GS, Violette SM, Munger JS. Mice that lack activity of alphavbeta6- and alphavbeta8-integrins reproduce the abnormalities of Tgfb1- and Tgfb3-null mice. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:227–32. doi: 10.1242/jcs.035246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hakkinen L, Koivisto L, Gardner H, Saarialho-Kere U, Carroll JM, Lakso M, Rauvala H, Laato M, Heino J, Larjava H. Increased expression of beta6-integrin in skin leads to spontaneous development of chronic wounds. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:229–42. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63113-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang XZ, Wu JF, Cass D, Erle DJ, Corry D, Young SG, Farese RV, Jr, Sheppard D. Inactivation of the integrin beta 6 subunit gene reveals a role of epithelial integrins in regulating inflammation in the lung and skin. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:921–8. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.4.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.AlDahlawi S, Eslami A, Hakkinen L, Larjava HS. The alphavbeta6 integrin plays a role in compromised epidermal wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2006;14:289–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mi Q, Riviere B, Clermont G, Steed DL, Vodovotz Y. Agent-based model of inflammation and wound healing: insights into diabetic foot ulcer pathology and the role of transforming growth factor-beta1. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15:671–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michaels J, Churgin SS, Blechman KM, Greives MR, Aarabi S, Galiano RD, Gurtner GC. db/db mice exhibit severe wound-healing impairments compared with other murine diabetic strains in a silicone-splinted excisional wound model. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15:665–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qiu Z, Kwon AH, Kamiyama Y. Effects of plasma fibronectin on the healing of full-thickness skin wounds in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J Surg Res. 2007;138:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greenhalgh DG, Sprugel KH, Murray MJ, Ross R. PDGF and FGF stimulate wound healing in the genetically diabetic mouse. Am J Pathol. 1990;136:1235–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt R, Wirtala J. Modification of Movat pentachrome stain with improved reliability of elastin staining. Journal of Histotechnology. 1996;19:325–7. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engvall E, Ruoslahti E. Binding of soluble form of fibroblast surface protein, fibronectin, to collagen. Int J Cancer. 1977;20:1–5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910200102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pal S, Chen Z, Xu X, Mikhailova M, Steffensen B. Co-purified gelatinases alter the stability and biological activities of human plasma fibronectin. J Periodont Res. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2009.01241.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Overall CM, Limeback H. Identification and characterization of enamel proteinases isolated from developing enamel. Amelogeninolytic serine proteinases are associated with enamel maturation in pig. Biochem J. 1988;256:965–72. doi: 10.1042/bj2560965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steffensen B, Wallon UM, Overall CM. Extracellular matrix binding properties of recombinant fibronectin type II-like modules of human 72-kDa gelatinase/type IV collagenase. High affinity binding to native type I collagen but not native type IV collagen. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11555–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shamsi FA, Partal A, Sady C, Glomb MA, Nagaraj RH. Immunological evidence for methylglyoxal-derived modifications in vivo. Determination of antigenic epitopes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6928–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stanley CM, Wang Y, Pal S, Klebe RJ, Harkless LB, Xu X, Chen Z, Steffensen B. Fibronectin fragmentation is a feature of periodontal disease sites and diabetic foot and leg wounds and modifies cell behavior. J Periodontol. 2008;79:861–75. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akiyama SK, Yamada SS, Chen WT, Yamada KM. Analysis of fibronectin receptor function with monoclonal antibodies: roles in cell adhesion, migration, matrix assembly, and cytoskeletal organization. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:863–75. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.2.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang X, Wu J, Spong S, Sheppard D. The integrin alphavbeta6 is critical for keratinocyte migration on both its known ligand, fibronectin, and on vitronectin. J Cell Sci. 1998;111(Pt 15):2189–95. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.15.2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rossini AA, Like AA, Chick WL, Appel MC, Cahill GF., Jr Studies of streptozotocin-induced insulitis and diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:2485–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.6.2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xie X, Li S, Liu S, Lu Y, Shen P, Ji J. Proteomic analysis of mouse islets after multiple low-dose streptozotocin injection. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:276–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Like AA, Rossini AA. Streptozotocin-induced pancreatic insulitis: new model of diabetes mellitus. Science. 1976;193:415–7. doi: 10.1126/science.180605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Riley WJ, McConnell TJ, Maclaren NK, McLaughlin JV, Taylor G. The diabetogenic effects of streptozotocin in mice are prolonged and inversely related to age. Diabetes. 1981;30:718–23. doi: 10.2337/diab.30.9.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rayat GR, Rajotte RV, Lyon JG, Dufour JM, Hacquoil BV, Korbutt GS. Immunization with streptozotocin-treated NOD mouse islets inhibits the onset of autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. J Autoimmun. 2003;21:11–5. doi: 10.1016/s0896-8411(03)00080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coleman DL. Obese and diabetes: two mutant genes causing diabetes-obesity syndromes in mice. Diabetologia. 1978;14:141–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00429772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coleman DL. Diabetes-obesity syndromes in mice. Diabetes. 1982;31:1–6. doi: 10.2337/diab.31.1.s1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Galiano RD, Michaels J, Dobryansky M, Levine JP, Gurtner GC. Quantitative and reproducible murine model of excisional wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2004;12:485–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2004.12404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature. 2001;414:813–20. doi: 10.1038/414813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xie Y, Gao K, Hakkinen L, Larjava HS. Mice lacking beta6 integrin in skin show accelerated wound repair in dexamethasone impaired wound healing model. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:326–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beer HD, Fassler R, Werner S. Glucocorticoid-regulated gene expression during cutaneous wound repair. Vitam Horm. 2000;59:217–39. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(00)59008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peppa M, Stavroulakis P, Raptis SA. Advanced glycoxidation products and impaired diabetic wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:461–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahmed N, Argirov OK, Minhas HS, Cordeiro CA, Thornalley PJ. Assay of advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs): surveying AGEs by chromatographic assay with derivatization by 6-aminoquinolyl-N-hydroxysuccinimidyl-carbamate and application to Nepsilon-carboxymethyl-lysine- and Nepsilon-(1-carboxyethyl)lysine-modified albumin. Biochem J. 2002;364:1–14. doi: 10.1042/bj3640001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berlanga J, Cibrian D, Guillen I, Freyre F, Alba JS, Lopez-Saura P, Merino N, Aldama A, Quintela AM, Triana ME, Montequin JF, Ajamieh H, Urquiza D, Ahmed N, Thornalley PJ. Methylglyoxal administration induces diabetes-like microvascular changes and perturbs the healing process of cutaneous wounds. Clin Sci (Lond) 2005;109:83–95. doi: 10.1042/CS20050026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morita K, Urabe K, Moroi Y, Koga T, Nagai R, Horiuchi S, Furue M. Migration of keratinocytes is impaired on glycated collagen I. Wound Repair Regen. 2005;13:93–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2005.130112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chong SA, Lee W, Arora PD, Laschinger C, Young EW, Simmons CA, Manolson M, Sodek J, McCulloch CA. Methylglyoxal inhibits the binding step of collagen phagocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8510–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609859200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sakata N, Sasatomi Y, Meng J, Ando S, Uesugi N, Takebayashi S, Nagai R, Horiuchi S. Possible involvement of altered RGD sequence in reduced adhesive and spreading activities of advanced glycation end product-modified fibronectin to vascular smooth muscle cells. Connect Tissue Res. 2000;41:213–28. doi: 10.3109/03008200009005291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]