Abstract

Adolescents with depression and high levels of oppositionality often are particularly difficult to treat. Few studies, however, have examined treatment outcomes among youth with both externalizing and internalizing problems. This study examines the effect of fluoxetine, cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), the combination of fluoxetine and CBT, and placebo on co-occurring oppositionality within a sample of depressed adolescents. All treatments resulted in decreased oppositionality at 12 weeks. Adolescents receiving fluoxetine, either alone or in combination with CBT, experienced greater reductions in oppositionality than adolescents not receiving antidepressant medication. These results suggest that treatments designed to alleviate depression can reduce oppositionality among youth with a primary diagnosis of depression.

Depression is common among adolescents (e.g., Kessler, Berglund et al., 2005) and is associated with a wide range of emotional, behavioral, and social problems (Fleming & Offord, 1990; Kessler, Avenevoli, & Merikangas, 2001; McCracken, 1992). A point prevalence rate of 7 to 8% (e.g., Kessler & Walters, 1998) has been found for depressive disorders among adolescents. Externalizing behavior problems are also common among youth. Documented point prevalence rates of conduct disorder (CD) in community samples have ranged from 1.8% (Esser, Schmidt, & Woerner, 1990) to 8.7% (Kashani, Beck et al., 1987; Kashani, Carlson et al., 1987). Prevalence rates of oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) have ranged between 3.2 and 13.3% for boys and between 1.4 and 9.4% for girls (Costello, Mustillo, Erkanli, Keeler, & Angold, 2003; Kroes et al., 2001; Maughan, Rowe, Messer, Goodman, & Meltzer, 2004; Nock, Kazdin, Hiripi, & Kessler, 2007). Further, depression and externalizing problems often co-occur, and this comorbidity is of public health importance given the association with suicide (Ezpeleta, Domenech, & Angold, 2006; Foley, Goldson, Costello, & Angold, 2006). In one study, 70% of adolescent suicide victims met criteria for both a mood disorder and an externalizing disorder (Shafii, Stelz-Lenarsky, Derrick, Beckner, & Wittinghill, 1988).

Even without meeting full criteria for both a depressive and disruptive disorder, many youth who present in the clinic have mixed symptom presentations. The negative affect of depression does indeed appear to share features of the oppositionality observed in disruptive behavior disorders. The presence of both symptom profiles has been found to result in increased functional impairment and a variety of challenging behaviors (e.g., Kovacs, Paulauskas, Constantine, & Richards, 1988), including poor social skills (Greene et al., 2002; Renouf, Kovacs, & Mukerji, 1997), problematic school behavior, and poor peer relationships (Cole & Carpentieri, 1990; Ezpeleta et al., 2006; Marmorstein & Iacono, 2001). Indeed, recent factor analytic work suggests that latent internalizing and externalizing factors are correlated (e.g., Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005). Oppositionality in youth has been found to have three dimensions: irritable, hurtful, and headstrong (Stringaris & Goodman, 2009). Studying oppositionality is important as it is likely that subthreshold oppositionality, or oppositionality that does not meet full criteria for ODD, is impairing in the lives of youth. This is particularly true in light of strong associations between oppositionality in youth and psychopathology in adult life (Nock et al., 2007).

On a larger level, the field of clinical psychology is moving toward a diagnostic system that allows for a mix of dimensional and classification criteria (e.g., Maser et al., 2009). This logic is based on the notion that the study of dimensions of symptoms will allow for greater symptom specificity. For these reasons, this study examines youth who meet criteria for depression and examines the effect of treatment on their levels of oppositionality, as defined dimensionally. This has implications for nosology, etiology, and the developmental progression of psychopathology. This dimensional investigation may also inform whether two diagnoses are warranted or whether oppositionality is a different manifestation of depression. First, however, we briefly summarize the treatment literature regarding comorbidity among youth.

Few studies have examined treatment outcomes among youth with both externalizing and internalizing problems. In a study evaluating the effect of imipramine on depression among boys, a decrease in CD behaviors was also observed among the boys with a comorbid CD diagnosis (Puig-Antich, 1982). Fluoxetine was evaluated in a study of male adolescents with comorbid depression, substance use, and CD, and found it to be efficacious in reducing symptoms of depression (Riggs, Mikulich, Coffman, & Crowley, 1997). Thus, some studies indicate that antidepressant medications can be effective in the treatment of depression among adolescents with comorbid CD. Some evidence to the contrary also exists. Among adolescents with comorbid major depressive disorder (MDD) and externalizing symptoms, lower rates of response to imipramine have been found relative to adolescents with depression only (Hughes et al., 1990). Only one of these studies (Hughes et al., 1990) included a placebo control. Recent practice parameters issued by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry for the treatment of youth with ODD (Steiner & Remsing, 2007) noted that there is limited evidence that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are helpful in the treatment of ODD in the context of comorbid mood disorders. These parameters recommend that medication target the primary syndrome, as comorbid oppositional behavior can complicate the treatment of a wide range of conditions. Thus, evidence regarding the effect of antidepressant medication on externalizing symptoms is inconclusive to date.

Evidence in support of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for adolescents with comorbid depression and externalizing behavior problems is also limited. Although originally cognitive-behavioral interventions were developed for youth presenting with one disorder (Hughes et al., 1990), recent work has begun to examine the effect of CBT on comorbid conditions among youth (e.g., Cornelius et al., 2009). CBT has been efficacious in the treatment of ODD and CD (for a review see Nock, 2003), and components of CBT used in the treatment of depression (e.g., cognitive restructuring, problem solving) have been successful in the treatment of CD and delinquency (Kazdin & Wassell, 2000). However, in a comparison of the efficacy and effectiveness of a cognitive behavioral group intervention for depressed adolescents with comorbid conduct disorder to a life skills/tutoring control, significant differences in CD remission or reductions in externalizing problem behaviors were not detected (Rohde, Clarke, Mace, Jorgensen, & Seeley, 2004). Few empirical studies document the efficacy and/or effectiveness of treatment for depressed youth with multiple problems, presenting a challenge for practicing clinicians.

The goal of this study was to investigate the effect of treatment for depression on comorbid oppositionality among adolescents with MDD participating in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS), a randomized controlled trial of empirically supported treatments for depressed adolescents (see TADS Team, 2004). This is in contrast to the original aims of the TADS trial, which were to examine different treatment effects on depression. The TADS trial examined the effects of CBT, fluoxetine (FLX), their combination (COMB), and a pill placebo with clinical management (PBO). Previous analyses of the TADS data suggest that, regardless of the randomized treatment, comorbidity predicted less improvement in depression symptoms after 12 weeks of acute treatment (Curry et al., 2006). Specifically, the presence of a comorbid disruptive behavior disorder did not predict acute outcome in TADS; however, a higher number of comorbid diagnoses (regardless of specific diagnosis) predicted less improvement in depression (Curry et al., 2006). As previous publications detail (TADS Team, 2004), all treatments resulted in statistically significant reductions in depression. In light of these results, we did not hypothesize that one treatment would affect oppositionality more than another. Rather, we explored the extent to which oppositionality decreased following treatment for depression. We used dimensional measurement of oppositionality to capture both subclinical and clinical thresholds of oppositionality and to explore the extent to which these symptoms were ameliorated with treatment. Indeed, a large percentage (61%) of the TADS sample fell into empirically derived subtypes of depression with mean levels of oppositionality in the clinically significant range (Herman, Ostrander, Walkup, Silva, & March, 2007). We hypothesized that (a) reductions in oppositionality would be observed in all four randomized treatments and (b) that these reductions would be partially accounted for by the reduction in depressive symptoms.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were 439 clinically depressed adolescents enrolled in the TADS. Sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health, the randomized controlled trial stage of TADS was designed to compare the effects of CBT (n = 111), FLX (n = 109), COMB, (n = 107), and PBO (n = 112) administered over a 12 week acute treatment period. Participants within the FLX and PBO arms were blinded to treatment condition; however, those in CBT and COMB were aware that they were receiving active treatment. Treatments were designed to meet best practice standards and were performed according to manuals (please see TADS Team, 2003). All sites (n = 13) participating in TADS obtained Institutional Review Board approval.

Adolescents in the TADS sample were between 12 and 17 years of age (inclusive) with a current primary Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed. [DSM–IV]; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnosis of MDD. Fifty-four percent of the participants were girls, 74% were Caucasian, and the mean age was 14.6 (SD = 1.5) years. A score of 45 or greater on the Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised (CDRS–R; Poznanski & Mokros, 1996) was required for study entry. The CDRS–R total scores at the pre-treatment assessment ranged from 45 to 98 (M = 60, SD = 10.4), indicative of mild to severe depression. This mean total CDRS–R score translates to a normed T score of 75.5 (SD = 6.43), suggesting moderate to severe depression. Further details of consent and assent, rationale, methods, design of the study, and other demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are detailed in previous reports (TADS Team, 2003, 2005). Fifty-two percent of enrolled adolescents presented with at least one comorbid psychiatric disorder, and 13.2% of adolescents presented with ODD. A disruptive behavior diagnosis did not predict premature termination or study dropout. Of note, the presence of severe conduct disorder was an exclusion criterion in TADS.

Procedures

Study assessments were conducted immediately prior to treatment (Baseline) and at two time points during the acute treatment period (Week 6 and Week 12). Clinical assessments were provided by an Independent Evaluator who was blind to treatment assignment. Several self-report questionnaires completed by youth and parents were collected.

Measures

Conners’ Parent Rating Scale–Revised (CPRS–R)

Oppositionality was assessed with the CPRS–R (Conners et al., 1997). The 80-item CPRS–R: Long Form was developed as a comprehensive checklist for acquiring parental reports of the presenting problems for children referred to outpatient psychiatric settings. Parents are asked to rate each item on the scale using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all true) to 3 (very much true). The items for the Oppositionality subscale include: angry and resentful, fights, argues with adults, loses temper, irritable, actively defies or refuses to comply with adults requests, touchy or easily annoyed by others, blames others for his/her mistakes, deliberately does things that annoy other people, and spiteful or vindictive. Coefficient alphas for the Oppositionality scale range between 0.89 and 0.92, indicating excellent internal reliability (Conners, Sitarenios, Parker, & Epstein, 1998). Cronbach’s alpha at baseline within our sample for the Oppositionality factor was very similar at 0.89. The Oppositionality factor assesses behaviors consistent with ODD and CD and excludes behaviors associated with ADHD, providing a useful and distinct measure of oppositional behavior (Conners et al., 1998) in line with the symptomatology of disruptive behavior disorders.

CDRS–R

The CDRS–R (Poznanski & Mokros, 1996) is a 17-item clinician-rated depression severity measure completed by the Independent Evaluator. Scores on the CDRS–R are based on interviews with the adolescent and parent and can range from 17 to 113, with higher scores representing more severe depression. The scale has good internal consistency (α = .85), interrater reliability (r = .92), test–retest reliability (r = .78) and is correlated with a range of validity indicators including global ratings and diagnoses of depression (Poznanski & Mokros, 1996). Within the current sample alpha was equal to .70.

Statistical Analyses

The primary outcome measure was level of oppositionality during the 12 week acute treatment period, as measured by the parent-report CPRS–R Oppositionality score. An intent-to-treat analysis approach was used with all 439 patients randomized to treatment included in the analysis regardless of study completion, protocol adherence, or treatment compliance. Fifteen participants were missing a CPRS–R oppositionality score at baseline. For these youth, the baseline sample median score (16.0) was imputed. Given that these analyses were exploratory, nondirectional statistical tests were conducted and the level of significance was set at p ≤ .05. Paired treatment contrasts were only conducted if omnibus tests were significant. An analysis of variance, with a posteriori t tests, was employed to compare the treatment arms on key baseline clinical characteristics. Pearson product-moment coefficients were calculated to examine the correlation between change in depression and oppositionality.

Effect of Treatment on Oppositionality

The impact of treatment on the CPRS–R Oppositionality score was modeled using a linear random coefficients regression model (RRM), which included the following: fixed effects for treatment, time, Treatment × Time, site, as well as random effects for participant. Nonsignificant interactions were removed from subsequent models to present the most parsimonious results. Under the assumption of random intercepts and slopes for each patient, the overall and treatment group-specific rates of change across the three available assessment points for the four treatment groups were examined. Pairwise comparisons on treatment slopes were then conducted.

Does Change in Depression Impact Oppositionality?

The first step of our analysis was to establish a relation between treatment and oppositionality. The second step estimating the effect of treatment on depression had already been established in prior reports (TADS Team, 2004). For the third step, depression change scores across the acute treatment period (baseline minus end of treatment difference scores) were used to determine whether a decrease in depression during the treatment period partially accounted for the oppositionality outcome. Change scores were employed rather than time-dependent depression scores to diminish any potential moderating effects of the pretreatment depression scores (H. C. Kraemer, personal communication, October 5, 2006). For the 60 youth missing a change score due to missing Week 12 data, a CDRS–R Week 12 score was imputed using the predicted score derived from the individual trajectories within the primary efficacy analysis (see TADS Team, 2004). As derived, a more positive change score represents a greater decrease in depression over the treatment period. Further analyses of adolescents who remitted (CDRS–R score less than or equal to 28) versus those who did not remit at Week 12 examined effects in more detail. Goodness of fit was assessed by a likelihood-ratio chi-square test, which is the difference between −2-log likelihood of the core model from that of the proposed model. This difference is distributed as a chi-square. The degrees of freedom for this test are equal to the difference between the number of estimated parameters in the proposed model and in the core model. To calculate the proportion of outcome variation accounted for by change in depression we used Singer and Willett’s (2003) pseudo-R2.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Patients in the four treatment conditions did not differ significantly at baseline with regard to CDRS–R depression severity, CPRS-R oppositionality, age at baseline, duration of the current depressive episode, or total number of comorbid psychiatric disorders. At baseline, oppositionality scores ranged from 0 to 30, with a median score of 16.0, which corresponds with a T score falling between 68 and 73 for boys and between 72 and 74 for girls.

Effect of Treatment on Oppositionality

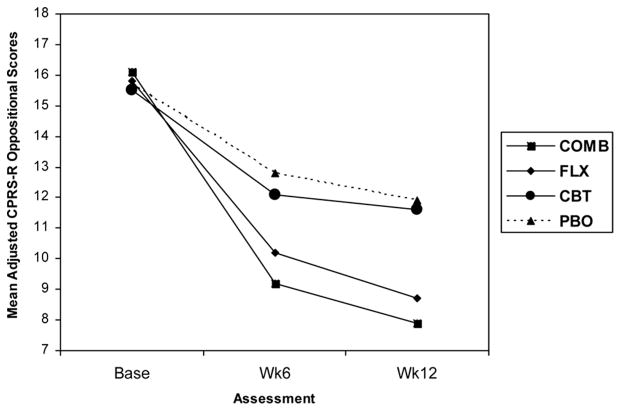

The correlation coefficient for change (baseline to Week 12) in depression with baseline oppositionality was r =−.03; p > .05. At Week 6, r = .19; p < .01, and at Week 12, r = .29, p < .01. Figure 1 displays change in oppositionality across the acute treatment period.

FIGURE 1.

Change in oppositionality over 12 weeks of treatment.

The RRM on longitudinal CPRS–R oppositional scores identified a statistically significant linear trend of time, F(1, 412) = 332.53, p < .01; site, F(12, 424) = 2.18, p = .01; and a Treatment × Time interaction, F(3, 412) = 12.62, p < .01. All other effects were not significant. Given that the omnibus test of Treatment × Time was significant, planned contrasts on the slope coefficients were conducted and produced a statistically significant ordering of outcomes. COMB (p < .01) and FLX (p < .01) were statistically significant when compared with PBO, whereas CBT (p > .05) was not. COMB was not superior to FLX (p > .05). Both COMB (p < .01) and FLX (p < .05) were superior to CBT. The slopes and Week 12 contrasts for the medication groups (COMB + FLX) were significantly different from the non-medication groups (CBT + PBO, both tests, p < .01), with the medication group experiencing a more rapid reduction in oppositionality than the nonmedication group. Further details on the slope coefficients and their standard errors are detailed in Table 1. Contrasts performed on Week 12 data points replicated these between-treatment results.

TABLE 1.

Fixed Effects of Time and Treatment × Time on Oppositionality Without and With Depression Change

| Fixed Effects | Without Depression |

With Depression |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | t | B | SE B | t | |

| Time | −0.81 | 0.14 | −5.86** | −0.33 | 0.15 | −2.16* |

| Treatment | ||||||

| FLX | 0.12 | 0.94 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.94 | 0.13 |

| CBT | −0.16 | 0.93 | −0.17 | −0.16 | 0.93 | −0.17 |

| COMB | 0.44 | 0.94 | 0.46 | 0.44 | 0.94 | 0.47 |

| Treatment × Time | ||||||

| FLX | −0.71 | 0.19 | −3.67** | −0.66 | 0.19 | −3.53** |

| CBT | −0.09 | 0.20 | −0.44 | −0.12 | 0.19 | −0.66 |

| COMB | −1.01 | 0.20 | −5.20** | −0.84 | 0.19 | −4.38** |

| AIC Model Fit | 7474.6 | 7447.6 | ||||

Note: All comparisons are made to pill placebo with clinical management. COMB = combination of fluoxetine (FLX) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT); AIC = Akaike’s information criterion.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

How Change in Depression Impacts the Effect of Treatment on Oppositionality

For the third step, depression change and Depression Change × Time were added to our original RRM model to determine if change in depression partially accounted for change in oppositionality. Significant time, F(1, 468) = 46.83, p < .01; site, F(12, 424) = 2.21, p = .01; and Depression Change × Time, F(1, 386) = 37.78, p < .01, effects were demonstrated for the oppositionality outcome. The effect of Treatment × Time was reduced in this model, F(3, 417) = 8.99, p < .01, but remained significant. This model offered a better fit for the observed data, Δχ2 = 27.00, Δdf = 1, p < .01, with a pseudo-R2 equal to 0.25, suggesting that 25% of change in oppositionality was accounted for by change in depression (Singer & Willett, 2003). COMB and FLX led to significantly greater rates of improvement in oppositionality when compared to PBO and CBT (all p < .01). COMB and FLX did not separate from one another (p > .05), which was also the case with CBT and PBO (p > .05). As such, the medication groups (COMB + FLX) resulted in greater rates of improvement than the non-medication groups (CBT + PBO; p < .01). Table 1 includes detail on slope coefficients. Contrasts conducted on slope estimates from baseline to Week 12 are reported in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Treatment by Time Slope Contrasts Without and With Depression Change

| Without Depression |

With Depression |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | df | F | df | |

| COMB vs. PBO | 13.44** | 1,415 | 12.43** | 1,417 |

| FLX vs. PBO | 10.32** | 1,411 | 8.11** | 1,415 |

| CBT vs. PBO | 2.39 | 1,411 | 0.82 | 1,416 |

| COMB vs. CBT | 27.00** | 1,413 | 19.14** | 1,421 |

| COMB vs. FLX | 0.19 | 1,414 | 0.43 | 1,416 |

| FLX vs. CBT | 22.43** | 1,405 | 13.60** | 1,420 |

Note: COMB = combination of fluoxetine (FLX) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT); PBO = pill placebo with clinical management.

p ≤ .01.

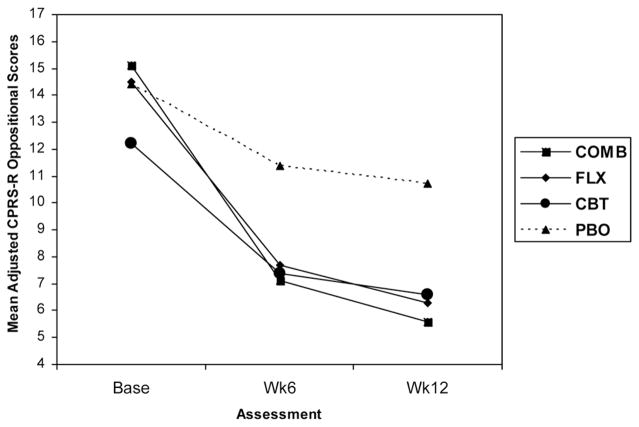

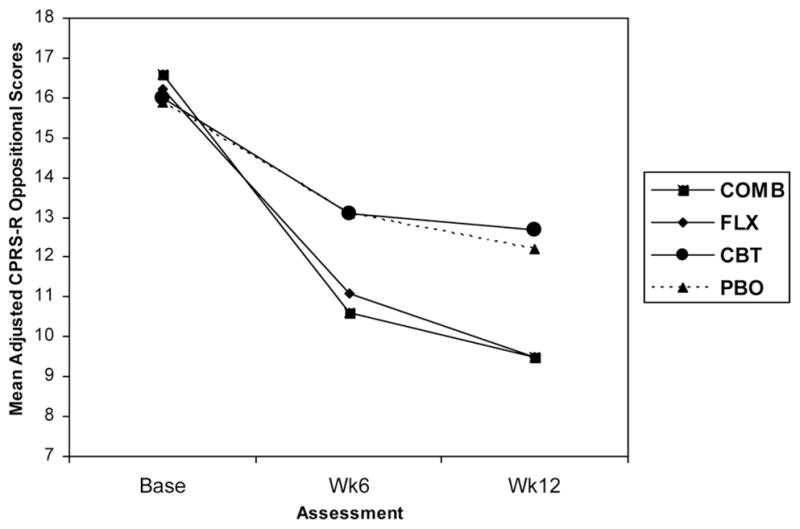

To further examine this effect we examined oppositionality outcomes among adolescents who remitted from depression at Week 12 (n = 56). Figures 2 and 3 illustrate that among adolescents whose depression was meaningfully reduced (e.g., reached remission status), all active treatments (COMB, FLX, CBT) resulted in significant reductions in oppositionality. In contrast, among adolescents who remained significantly depressed, CBT did not lead to more improvement in oppositionality than PBO.

FIGURE 2.

Change in oppositionality over 12 weeks of treatment among remitters. Oppositionality scores are adjusted for the fixed (treatment, time, Treatment × Time, site) and random effects (patient, Patient × Time) included in the random coefficients regression model. Remission was defined as a Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised score less than or equal to 28. Note. COMB = combination of fluoxetine (FLX) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT); PBO = pill placebo with clinical management.

FIGURE 3.

Change in oppositionality over 12 weeks of treatment among non-remitters. Oppositionality scores are adjusted for the fixed (treatment, time, Treatment × Time, site) and random effects (patient, Patient × Time) included in the random coefficients regression model. Remission was defined as a Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised score less than or equal to 28. Note. COMB = combination of fluoxetine (FLX) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT); PBO = pill placebo with clinical management.

In summary, antidepressant treatment led to significantly lower oppositionality scores at Week 12 when compared to youth not receiving active medication. Change in depression partially accounted for the reduction in oppositionality, as revealed by the significant Depression × Time effect. Although the effect of change in depression reduced the Treatment × Time interaction effect on oppositionality, it remained statistically significant. Thus, we conclude that change in depression over the course of treatment contributed to the observed effect of treatment on oppositionality.

DISCUSSION

Findings from the TADS trial suggest that acute treatments for depression can reduce oppositionality among clinically depressed adolescents. All treatments, but particularly those including medication management with FLX, reduced oppositionality from clinical to subclinical levels. Treatments that included a medication component resulted in large effects, in line with Cohen’s (1988) benchmarks, when compared to placebo. Among adolescents whose depression was adequately treated (i.e., reached remission status), CBT resulted in greater improvement than PBO in oppositionality. In contrast, among adolescents whose depression did not remit, CBT did not differ from PBO.

Our results are congruent with the concept of “dynamic comorbidity” between externalizing and internalizing disorders (Lahey, Loeber, Burke, Rathouz, & McBurnett, 2002), wherein within-child changes in conduct disorder behaviors have been found to parallel within-child changes in depression. From this perspective, treatment of depression would contribute to improvements in co-occurring disruptive behavior disorders. Several “core processes” (McCarty, Stoep, & McCauley, 2007), such as low self-worth and negative self-image, may represent general risk factors for both forms of psychopathology. Negative emotionality (Eisenberg, Fabes, Guthrie, & Reiser, 2000), personal and familial risk factors (Fergusson, Lynskey, & Horwood, 1996), as well as deficits in information processing and affect regulation (Larson, Diener, & Cropanzano, 1986) have also been proposed. Our findings may support the notion that oppositionality is a different manifestation or specific subtype of depression. Indeed, among adults, research has identified distinct psychological and neuroendocrine profiles for those presenting with highly irritable and hostile depression (Fava et al., 1993; Rosenbaum et al., 1993). Further nosological research is needed to adequately identify and describe these overlapping processes.

Although our results suggest that fluoxetine may be helpful for the acute treatment of oppositional behavior and depression in adolescents, clinicians must take care when treating this population. Given the U.S. Food and Drug Administration warning of October 15, 2004, regarding the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors among youth, particular attention is warranted in monitoring suicidality. This is especially relevant given the increased risk of suicidality associated with subthreshold externalizing symptoms in the context of mood disorders (Foley et al., 2006). That said, our findings indicate that treating the primary disorder of depression appears to simultaneously ameliorate oppositionality.

Our confidence in the results obtained is limited by several factors. First, our findings may not generalize to youth with more severe externalizing behavior problems, or to youth seen in community settings. Our measure of oppositionality was derived from a well-validated parent report measure. The use of alternative, behaviorally based or observational methods is recommended for future research. Ideally, future research will include multimethod assessment designed to capture the nuanced nature of these overlapping symptoms in multiple contexts. However, in light of recent evidence that latent subtypes of adolescent depression exist (Herman et al., 2007), as well as the fact that depressed-only presentations represent a minority of clinical cases, the current study demonstrates that existing treatments can be helpful in treating the prevalent oppositional-depressed presentation. Another limitation of our investigation is our inability to consider mediation effects among a sample of youth with comorbid diagnoses of ODD or CD. Levels of these diagnoses in our sample did not offer adequate statistical power. Future work replicating our findings in a sample meeting diagnostic criteria for both a disruptive behavior disorder and depression would be informative. In addition, specific attention to the timing of such mediation effects is warranted. It is also true that treatment blindness varied by condition. It is possible that differences in treatment blindness impacted oppositionality outcomes. Last, symptoms of oppositionality, such as irritability, overlap with symptoms of depression. It is possible that our results stem in part from an overlap in constructs. However, we believe that this is unlikely given that the entire sample was clinically depressed, but every teen did not display a high score on the Oppositionality subscale. Nevertheless, the possibility that our mediation results are due to an overlap in constructs or symptoms cannot be ruled out and may be addressed in future research.

Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice

There are a number of conclusions we can draw from this work. First, clinicians would do well to assess oppositionality in depressed adolescents when considering different treatment modalities. In regards to medication management, suicidality must be considered. Clinicians may find a dimensional approach to oppositionality particularly useful in approaching treatment with youth who have mixed presentations. Second, treatments that alleviate depression can reduce oppositionality among clinically depressed youth with co-occurring symptomatology. Medication management with fluoxetine appears to be effective, either as a monotherapy or as part of combination treatment for alleviating depression. Moreover, robust effects can be seen in a relatively short period. Third, evaluating the effects of factors such as life events and environmental influences will be important in understanding possible mechanisms of therapeutic change in youth with multiple problems. Research identifying cognitive and social processes that maintain depression and externalizing disorders may allow for the adaptation of CBT to systematically address these symptom profiles.

Acknowledgments

TADS is supported by contract N01 MH80008 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) to Duke University Medical Center (John S. March, Principal Investigator). Preparation of this manuscript was supported by NIMH fellowship F31 MH075308 to Rachel H. Jacobs. The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study is coordinated by the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and the Duke Clinical Research Institute at Duke University Medical Center in collaboration with the NIMH, Rockville, Maryland. The Coordinating Center principal collaborators are John March, Susan Silva, Stephen Petrycki, John Curry, Karen Wells, John Fairbank, Barbara Burns, Marisa Domino, and Steven McNulty. The NIMH principal collaborators are Benedetto Vitiello and Joanne Severe. Principal Investigators and Co-Investigators from the clinical sites are as follows: Carolinas Medical Center: Charles Casat, Jeanette Kolker, Karyn Riedal, Marguerita Goldman; Case Western Reserve University: Norah Feeny, Robert Findling, Sheridan Stull, Felipe Amunategui; Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia: Elizabeth Weller, Michele Robins, Ronald Weller, Naushad Jessani; Columbia University: Bruce Waslick, Michael Sweeney, Rachel Kandel, Dena Schoenholz; Johns Hopkins University: John Walkup, Golda Ginsburg, Elizabeth Kastelic, Hyung Koo; University of Nebraska: Christopher Kratochvil, Diane May, Randy LaGrone, Martin Harrington; New York University: Anne Marie Albano, Glenn Hirsch, Tracey Knibbs, Emlyn Capili; University of Chicago/Northwestern University: Mark Reinecke, Bennett Leventhal, Catherine Nageotte, Gregory Rogers; Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center: Sanjeev Pathak, Jennifer Wells, Sarah Arszman, Arman Danielyan; University of Oregon: Anne Simons, Paul Rohde, James Grimm, Lananh Nguyen; University of Texas Southwestern: Graham Emslie, Beth Kennard, Carroll Hughes, Maryse Ruberu; Wayne State University: David Rosenberg, Nili Benazon, Michael Butkus, Marla Bartoi. Greg Clarke (Kaiser Permanente) and David Brent (University of Pittsburgh) are consultants; James Rochon (Duke University Medical Center) is statistical consultant.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Susan Silva is a consultant with Pfizer. John March is a consultant or scientific advisor to Pfizer, Lilly, Wyeth, GSK, Jazz, and MedAvante and holds stock in MedAvante; he receives research support from Lilly and study drug for an NIMH-funded study from Lilly and Pfizer. The other authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

Contributor Information

Rachel H. Jacobs, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

Emily G. Becker-Weidman, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

Mark A. Reinecke, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

Neil Jordan, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

Susan G. Silva, Duke University School of Nursing, Duke University School of Medicine, and Duke Clinical Research Institute

Paul Rohde, Oregon Research Institute.

John S. March, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University Medical Center

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Carpentieri S. Social status and the comorbidity of child depression and conduct disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:748–757. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.6.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners K, Wells K, Parker J, Sitarenios G, Diamond J, Powell J. A new self-report scale for assessment of adolescent psychopathology: Factor structure, reliability, validity, and diagnostic sensitivity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25:487–497. doi: 10.1023/a:1022637815797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK, Sitarenios G, Parker J, Epstein JN. The Revised Conners’ Parent Rating Scale (CPRS–R): Factor structure, reliability, and criterion validity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;26:257–268. doi: 10.1023/a:1022602400621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Bukstein OG, Wood DS, Kirisci L, Douaihy A, Clark DB. Double-blind placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine in adolescents with comorbid major depression and an alcohol use disorder. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:905–909. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry J, Rohde P, Simons A, Silva S, Vitiello B, Kratochvil C, et al. Predictors and moderators of acute outcome in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:1427–1439. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000240838.78984.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, Reiser M. Dispositional emotionality and regulation: Their role in predicting quality of social functioning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:136–157. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esser G, Schmidt MH, Woerner W. Epidemiology and course of psychiatric disorders in school-age children: Results of a longitudinal study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1990;31:243–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1990.tb01565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezpeleta L, Domenech JM, Angold A. A comparison of pure and comorbid CD/ODD and depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:704–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, Rosenbaum J, Pave J, McCarthy M, Steingard R, Bouffides E. Anger attacks in unipolar depression part I: Clinical correlates and response to fluoxetine treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:1158–1163. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.8.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Lynskey M, Horwood LJ. Origins of comorbidity between conduct and affective disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:451–460. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199604000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming J, Offord D. Epidemiology of childhood depressive disorders: A critical review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1990;29:571–580. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199007000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley DL, Goldston DB, Costello EJ, Angold A. Proximal psychiatric risk factors for suicidality in youth: The Great Smoky Mountains Study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:1017–1024. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.9.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration. Public health advisory: Suicidality in children and adolescents being treated with antidepressant medications. 2004 October 15; Retrieved January 10, 2010, from http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PublicHealthAdvisories/ucm161679.htm.

- Greene RW, Biederman J, Zerwas S, Monuteaux MC, Goring JC, Faraone SV. Psychiatric comorbidity, family dysfunction, and social impairment in referred youth with oppositional defiant disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1214–1224. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman KC, Ostrander R, Walkup JT, Silva SG, March JS. Empirically derived subtypes of adolescent depression: Latent profile analysis of co-occurring symptoms in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:716–728. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CW, Preskorn S, Weller E, Weller R, Hassanein R, Tucker S. The effect of concomitant disorders in childhood depression on predicting treatment response. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1990;26:235–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashani JD, Beck N, Hoeper E, Fallahi C, Corcoran C, McAllister J, et al. Psychiatric disorders in a community sample of adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;144:584–589. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.5.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashani JD, Carlson G, Beck N, Hoeper E, Corcoran C, McAllister J, et al. Depression, depressive symptoms, and depressed mood among a community sample of adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;144:931–934. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.7.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin A, Wassell G. Therapeutic changes in children, parents, and families resulting from treatment of children with conduct problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:414–420. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200004000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Merikangas KR. Mood disorders in children and adolescents: An epidemiologic perspective. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49:1002–1014. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM–IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Walters EE. Epidemiology of DSM–III–R major depression and minor depression among adolescents and young adults in the National Comorbidity Survey. Depression and Anxiety. 1998;7:3–14. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6394(1998)7:1<3::aid-da2>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, Paulauskas S, Constantine C, Richards C. Depressive disorders in childhood III. A longitudinal study of comorbidity with and risk for conduct disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1988;15:205–217. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroes M, Kalff A, Kessels A, Steyaert J, Feron FJM, van Someren A, et al. Child psychiatric diagnoses in a population of Dutch school children aged 6 to 8 years. Journal of the Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:1401–1409. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200112000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey B, Loeber R, Burke J, Rathouz P, McBurnett K. Waxing and waning in concert: Dynamic comorbidity of conduct disorder with other disruptive and emotional problems over 7 years among clinic-referred boys. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:556–567. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Diener E, Cropanzano R. Cognitive operations associated with individual differences in affect intensity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;53:767–744. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.4.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein NR, Iacono WG. An investigation of female adolescent twins with both major depression and conduct disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:299–306. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200103000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maser JD, Norman SB, Zisook S, Everall IP, Stein MB, Schettler PJ, et al. Psychiatric nosology is ready for a paradigm shift in DSM–V. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2009;16:24–40. [Google Scholar]

- Maughan B, Rowe R, Messer J, Goodman R, Meltzer H. Conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder in a national sample: Developmental epidemiology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:609–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty C, Stoep AV, McCauley E. Cognitive features associated with depressive symptoms in adolescence: Directionality and specificity. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:147–158. doi: 10.1080/15374410701274926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken J. The epidemiology of child and adolescent mood disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1992;1:53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK. Progress review of the psychosocial treatment of child conduct problems. Clinical Psychology Science & Practice. 2003;10:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Kazdin AE, Hiripi E, Kessler RC. Lifetime prevalence, correlates, and persistence of oppositional defiant disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:703–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznanski EO, Mokros HB. Children’s depression rating scale, revised. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Puig-Antich J. Major depression and conduct disorder in pre-puberty. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1982;21:118–128. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60910-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renouf AG, Kovacs M, Mukerji P. Relationship of depressive, conduct, and comorbid disorders and social functioning in childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:998–1004. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs PD, Mikulich SK, Coffman LM, Crowley TJ. Fluoxetine in drug-dependent delinquents with major depression: An open trial. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 1997;7:87–95. doi: 10.1089/cap.1997.7.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Clarke GN, Mace DE, Jorgensen JS, Seeley JR. An efficacy/effectiveness study of cognitive-behavioral treatment for adolescents with comorbid major depression and conduct disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:660–668. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000121067.29744.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum J, Fava M, Pava J, McCarthy M, Steingard R, Bouffides E. Anger attacks in unipolar depression, part 2: Neuroendocrine correlates and changes following fluoxetine treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:1164–1168. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.8.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafii M, Stelz-Lenarsky J, Derrick A, Beckner C, Wittinghill J. Comorbidity of mental disorders in the post-mortem diagnosis of completed suicide in children and adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1988;15:227–233. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner H, Remsing L. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with oppositional defiant disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:126–141. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000246060.62706.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Goodman R. Three dimensions of oppositionality in youth. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:216–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TADS Team. Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS): Rationale, design, and methods. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:531–542. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046839.90931.0D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TADS Team. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292:807–820. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.7.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TADS Team. The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS): Demographic and clinical characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:28–40. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000145807.09027.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]