Abstract

Bacterial nanowires are extracellular appendages that have been suggested as pathways for electron transport in phylogenetically diverse microorganisms, including dissimilatory metal-reducing bacteria and photosynthetic cyanobacteria. However, there has been no evidence presented to demonstrate electron transport along the length of bacterial nanowires. Here we report electron transport measurements along individually addressed bacterial nanowires derived from electron-acceptor–limited cultures of the dissimilatory metal-reducing bacterium Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Transport along the bacterial nanowires was independently evaluated by two techniques: (i) nanofabricated electrodes patterned on top of individual nanowires, and (ii) conducting probe atomic force microscopy at various points along a single nanowire bridging a metallic electrode and the conductive atomic force microscopy tip. The S. oneidensis MR-1 nanowires were found to be electrically conductive along micrometer-length scales with electron transport rates up to 109/s at 100 mV of applied bias and a measured resistivity on the order of 1 Ω·cm. Mutants deficient in genes for c-type decaheme cytochromes MtrC and OmcA produce appendages that are morphologically consistent with bacterial nanowires, but were found to be nonconductive. The measurements reported here allow for bacterial nanowires to serve as a viable microbial strategy for extracellular electron transport.

Keywords: bioelectronics, microbial fuel cells, bioenergy

Electron transfer is fundamental to biology: organisms extract electrons from a wide array of electron sources (fuels) and transfer them to electron acceptors (oxidants). Prokaryotes can use a wide variety of dissolved electron acceptors (such as oxygen, nitrate, and sulfate) that are accessible to their intracellular enzymes. However, dissimilatory metal-reducing bacteria (DMRB) are challenged by the low solubility of solid phase Fe(III) and Mn(IV) minerals that serve as their terminal electron acceptors, and therefore use extracellular electron transfer to overcome this obstacle (1). Various strategies of extracellular electron transfer have been reported for metal-reducing bacteria, including naturally-occurring (2) and biogenic (3–5) soluble mediators that shuttle electrons from cells to acceptors, as well as direct transfer using multiheme cytochromes associated with the outer membrane (6). Recent reports have also suggested that extracellular electron transport may be facilitated by conductive filamentous extracellular appendages called bacterial nanowires (7–9). The first report found bacterial nanowires in the DMRB Geobacter (7). A subsequent scanning tunneling microscopy study (8) demonstrated transverse electrical conduction in nanowires from other microorganisms, including another metal reducer (Shewanella oneidensis MR-1), an oxygenic photosynthetic cyanobacterium (Synechocystis PCC6803), and a thermophilic fermentative bacterium (Pelotomaculum thermopropionicum), when cultivated under conditions of electron acceptor limitation.

To date, several biological assays have demonstrated results consistent with electron transport along bacterial nanowires, including measurements of improved electricity generation in microbial fuel cells and enhanced microbial reduction of solid-phase iron oxides (7, 8, 10). However, our direct knowledge of nanowire conductivity has been limited to local measurements of transport only across the thickness of the nanowires (7–9). Thus far, there has been no evidence presented to verify electron transport along the length of bacterial nanowires, which can extend many microns, well beyond a typical cell's length. Here we report electron transport measurements along individually addressed bacterial nanowires derived from electron-acceptor limited cultures of the DMRB S. oneidensis MR-1.

Results

Direct Transport Measurements Using Nanofabricated Electrodes.

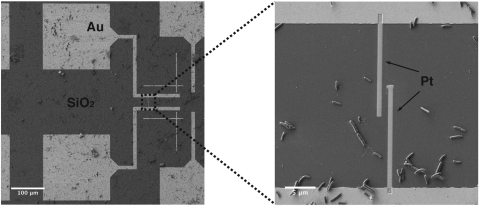

To fabricate two-contact devices, chemically fixed samples from continuous cultures were deposited on SiO2/Si substrates with prepatterned metallic contact pads. The substrates were subsequently dehydrated in ethanol, critical-point dried, and examined using a dual-column scanning electron/focused ion beam (FIB) microscope. Individual bacterial nanowires were located using secondary electron imaging and were then contacted by ion beam- or electron beam-induced deposition of platinum electrodes (Fig. 1). Current-voltage (I-V) sweeps were collected at ambient conditions using probe stations instrumented to semiconductor parameter analyzers.

Fig. 1.

Contacting individual bacterial nanowires with nanofabricated Pt electrodes. SEM images showing the geometry of the prefabricated Au contacts on SiO2/Si. The zoom-in shows the FIB-deposited Pt contacts addressing a bacterial nanowire emanating from a S. oneidensis MR-1 cell.

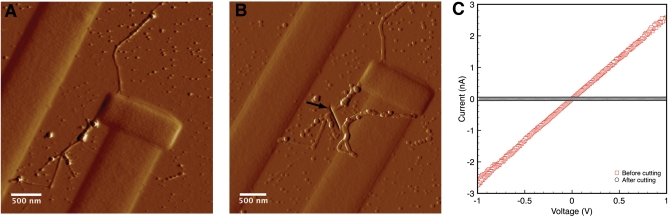

Fig. 2 illustrates the results from a single bacterial nanowire extending from a wild-type S. oneidensis MR-1 cell. Following deposition of the Pt contacts (Fig. 2A), we observed an ohmic current response to applied voltage (Fig. 2C) with resistance R = 386 MΩ, yielding a corresponding electron transport rate, at 100 mV, of about 109 electrons per second. The resistivity estimated from this measurement is 1 Ω·cm (Materials and Methods), comparable in magnitude to that of moderately doped silicon nanowires (11). To confirm that the nanowire provides the only conductive path between the electrodes, a FIB was used to cut the nanowire without disturbing the rest of the device (Fig. 2B). After the nanowire was cut, there was no measurable current response to applied voltage (Fig. 2C), confirming that the observed conduction path was indeed through the nanowire. In addition to the nanowire of Fig. 2, two more bacterial nanowires, sampled from a different bioreactor, were investigated for electrical transport using nanofabricated electrodes, resulting in measured resistivities of 4 Ω·cm (R = 465 MΩ) (Fig. S1A) and 17 Ω·cm (R = 2.3 GΩ) (Fig. S1B).

Fig. 2.

Measuring electrical transport along a bacterial nanowire. (A) Tapping-mode atomic force microscopy (AFM) amplitude image detailing the contact area with the bacterial nanowire from Fig. 1. (B) Contact-mode AFM deflection image of the junction after cutting the nanowire with FIB milling. The arrow marks the cut location. (C) Current-voltage curve of the bacterial nanowire (ramp-up and ramp-down) both before (red) and after (black) cutting the nanowire.

Conducting Probe Atomic Force Microscopy.

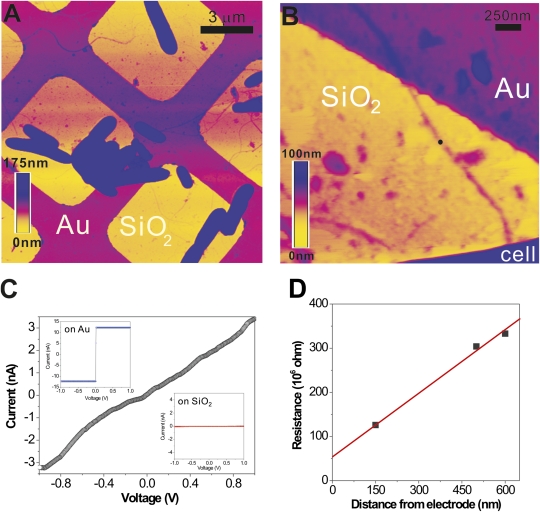

To determine whether the resistivity values obtained from our two-contact devices include a significant contribution from contact resistance between electrodes and nanowires, conducting probe atomic force microscopy (CP-AFM) was used to measure the resistance of a single nanowire as a function of its length. CP-AFM is a convenient tool for probing local electrical properties at the nanometer scale, and has been increasingly used for the electrical characterization of biological molecules (12–14). CP-AFM was also previously employed to demonstrate transverse conduction through bacterial nanowires produced by Geobacter sulfurreducens (7) and S. oneidensis MR-1 (9). In the previous experiments, however, the nanowires were supported on conductive surfaces of highly ordered pyrolytic graphite, precluding measurements of their longitudinal conduction. To verify longitudinal transport along bacterial nanowires using CP-AFM, S. oneidensis MR-1 nanowires from chemically fixed samples were immobilized on SiO2/Si substrates with lithographically patterned Au microgrids as electrodes (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

CP-AFM of a bacterial nanowire. (A) Topographic AFM image showing air-dried S. oneidensis MR-1 cells and extracellular appendages deposited randomly on a SiO2/Si substrate patterned with Au microgrids. (B) Contact mode AFM image showing a nanowire reaching out from a bacterial cell to the Au electrode. (C) An I-V curve obtained by probing the nanowire at a length of 600 nm away from the Au electrode (at the position marked by the black dot in B). (Inset) The I-V curves obtained on bare Au and SiO2, respectively. (D) A plot of total resistance as a function of distance between AFM tip and Au electrode.

Electronic transport along a nanowire in contact with the Au microgrid was measured by using the Pt-coated AFM tip as a second electrode. With the AFM tip at the position shown in Fig. 3B, ~600 nm away from the Au electrode and in contact with the nanowire, we obtained the I-V curve shown in Fig. 3C. The current response to the applied voltage was found to be approximately linear and consistent with the results obtained using nanofabricated Pt electrodes (Fig. 2). As a control, we observed that whenever the AFM tip was placed directly on the SiO2 surface, we obtained a background current of ~10 pA (Fig. 3C, Inset), confirming that extraneous conduction through adsorbed water layers or other contaminants was negligible.

Fig. 3D shows multiple measurements on the same nanowire at different points along its length. We observed a linear relationship between measured resistance and length, allowing us to extrapolate the curve to zero length to estimate the overall contact resistance. We obtained a value of 58 MΩ that, when subtracted from the total resistance, yields a bulk resistivity for the nanowire on the order of 1 Ω·cm, in agreement with measurements using nanofabricated Pt electrodes (Fig. 2).

Nonconductive Appendages Produced by S. oneidensis MR-1 Mutants Deficient in MtrC and OmcA.

We also studied mutants (ΔmtrC/omcA) lacking genes for multiheme c-type cytochromes MtrC and OmcA (8). The ΔmtrC/omcA mutants were cultivated in continuous flow bioreactors under identical conditions as wild-type MR-1. In response to electron acceptor limitation, the ΔmtrC/omcA mutants produced appendages morphologically consistent with wild-type nanowires (Fig. S2). A total of seven appendages, from seven different ΔmtrC/omcA cells and two bioreactor samples, were contacted by nanofabricated electrodes and tested for electrical conductivity (Fig. S2). The ΔmtrC/omcA appendages were found to be nonconductive, showing no current response to applied voltage down to the noise floor.

Discussion

The discovery of bacterial nanowires spawned a common question among microbiologists, biogeochemists, and physicists: Can nanowires transport electrons along their entire length, and with what resistivity? To answer this question, we evaluated transport along bacterial nanowires by two independent techniques: (1) nanofabricated electrodes patterned on top of individual nanowires, and (2) CP-AFM at various points along a single nanowire bridging a metallic electrode and the conductive AFM tip. The S. oneidensis nanowires were found to be electrically conductive along micrometer-length scales with electron transport rates up to 109/s at 100 mV of applied bias and a measured resistivity on the order of 1 Ω·cm.

Recent measurements by McLean et al. of the rate of electron transfer per cell from S. oneidensis MR-1 to fuel cell anodes were on the order of 106 electrons per cell per second (15). These measurements are consistent with the specific respiration rate estimated under the cultivation conditions used here (2.6 × 106 electrons per cell per second) (Materials and Methods). A comparison with our transport measurements demonstrates that a single bacterial nanowire could discharge this entire supply of respiratory electrons to a terminal acceptor.

A previous scanning tunneling microscopy study (8) associated c-type cytochromes with the conductivity of bacterial nanowires from S. oneidensis MR-1. To identify the role of cytochromes in nanowires, we studied mutants (ΔmtrC/omcA) lacking genes for multiheme c-type cytochromes MtrC and OmcA. We found that these mutants produce nonconductive filaments, indicating that, in the case of S. oneidensis MR-1, cytochromes are necessary for conduction along nanowires. However, this finding does not preclude other mechanisms for long-range electron transport along bacterial nanowires from other organisms. For example, Geobacter nanowires are presumed to be conductive as a result of the amino acid sequence of the type IV pilin subunit, PilA, and, possibly, the tertiary structure of the assembled pilus (7).

In conclusion, our data demonstrate electrical transport along bacterial nanowires from S. oneidensis MR-1, with transport rates that allow for bacterial nanowires to serve as a viable microbial strategy for extracellular electron transport. The measurements reported here motivate further investigations into the molecular composition and physical transport mechanism of bacterial nanowires, both to understand and realize the broad implications for natural microbial systems and biotechnological applications such as microbial fuel cells.

Materials and Methods

Cultivation.

S. oneidensis strain MR-1 (wild-type) and the double-deletion mutant ΔmtrC/omcA lacking two decaheme cytochromes were cultured in continuous flow bioreactors (BioFlo 110; New Brunswick Scientific) with a dilution rate of 0.05 h−1 and an operating liquid volume of 1 L. A chemically defined medium was used with lactate as the sole electron donor, and conditions were maintained as previously described by Gorby et al. (8) to achieve electron acceptor limitation. Appendages were produced in response to electron acceptor (O2) limitation, when the dissolved O2 tension was lowered below the detection of the polarographic O2 electrode.

An estimate of the specific respiration rate was calculated as follows: Starting with a wild-type S. oneidensis MR-1 bioreactor in steady state condition, cell density was determined using a Petroff-Hauser counting chamber to be 7.72 × 108 cells/mL. The flow of growth medium to the reactor was then shut off. Shortly thereafter, all the remaining electron donor (lactate) was consumed, triggering a rapid increase in dissolved O2 concentration. Next, lactate was added to the reactor to a final concentration of 50 mM, with the oxidation of lactate immediately causing a rapid decrease in dissolved O2 concentration. A subsequent rapid increase in dissolved O2 concentration indicated that the lactate had been consumed. By measuring the time it took for the 50 mM lactate to be consumed (180 s), extracting 12 electrons per lactate molecule, and knowing the cell density, we calculate the rate of electron transfer per cell to be 2.6 × 106 electrons per cell per second.

Nanofabricated Devices.

Sample preparation.

Samples for electrical measurements using nanofabricated electrodes were removed from steady-state bioreactor cultures and immediately fixed using glutaraldehyde (2.5% concentration). Fixed samples were applied to oxidized Si chips with prepatterned Au contacts (Fig. 1) and subjected to a serial dehydration protocol using increasing concentrations of ethanol (10, 25, 50, 75, and finally 100% vol/vol ethanol). The dehydrated samples were then critical-point dried and desiccated for further nanofabrication processing.

Electrode fabrication.

Imaging and deposition were carried out using Zeiss 1540 XB FIB/SEM Etching/Deposition Systems. Cells with attached nanowires were located in the proximity of the prefabricated Au contacts. A Pt precursor was then introduced to the chamber using a gas injection system and electrodes were directly deposited to contact the bacterial nanowires using ion beam- (10 pA FIB current) or electron beam-induced chemical vapor deposition. The electrode sections in contact with the prefabricated Au contacts were always deposited by the FIB (which mills as it deposits), thus cleaning the prefabricated patterns of any cellular material that may have accumulated during sample preparation.

Electrical measurements.

Current-voltage (I-V) measurements were performed at room temperature using probe stations instrumented to either an Agilent 4156C semiconductor parameter analyzer or an Agilent B1500A analyzer. Results for three successful measurements of transport along bacterial nanowires from three different wild-type S. oneidensis MR-1 cells and two different samples are shown in Fig. 2 and Fig. S1. For each nanowire tested, resistance was calculated from the ohmic current-voltage (I-V) trace. Knowing the resistance (R, in Ω), the resistivity (ρ, in Ω·cm) was calculated using  , where L is the length of the nanowire segment between the two probes (measured by SEM or AFM imaging) and A is the cross sectional nanowire area (calculated using AFM height measurements described below).

, where L is the length of the nanowire segment between the two probes (measured by SEM or AFM imaging) and A is the cross sectional nanowire area (calculated using AFM height measurements described below).

Electrode characterization and controls.

The Pt electrodes deposited by beam induced chemical vapor deposition were characterized separately to assess their contribution to the measured resistance. Fig. S3A shows a FIB-deposited Pt line (30-nm thick, 1-μm wide, 27-μm long) connecting the prefabricated Au patterns. From a current of 93.2 μA at 1V, the resistivity of the FIB-deposited Pt is calculated to be about 10−3 Ω·cm, including some contribution from the contact resistance between the Pt and prefabricated Au. This resistivity value is higher than the resistivity of bulk Pt, which is expected because of the carbon and gallium contamination inherent in the FIB deposition process, but is still a small contribution to the overall resistance of the junctions involving bacterial nanowires (>100 MΩ in Fig. 2 and Fig. S1). In addition to cutting a bacterial nanowire (Fig. 2), another open-circuit control was conducted (Fig. S3B) by placing two Pt probes very close together (<150 nm without a bridging nanowire) on a chip that underwent the same glutaraldehyde fixation, dehydration, and critical-drying protocol as the bacterial nanowire junctions. This sample also showed no current response to applied voltage, further ruling out any metallic contamination between the electrodes under the deposition conditions used in this study.

AFM of nanofabricated devices.

Following nanofabrication and electrical measurements, samples were inspected using a Veeco Innova AFM employing either tapping mode (Fig. 2A) or contact mode (Fig. 2B). The typical appendage height was found to be 8–10 nm (Fig. S4). A typical electrode thickness, for the deposition conditions used here, was 30–40 nm. Repeated AFM scanning after electrode deposition and successful I-V measurements but before cutting the nanowire of Fig. 2 displaced some extracellular debris close to the junction area (e.g., placing material near the right electrode in Fig. 2B compared with Fig. 2A), but the junction remained conductive.

CP-AFM.

Sample preparation.

Au microgrids were fabricated on a SiO2/Si substrate by standard photolithographic patterning followed by electron-beam vapor deposition of 3 nm of Cr (as an adhesion layer) and 20 nm of Au. Samples were harvested from the bioreactor, fixed using 2.5% glutaraldehyde, and applied to the Au microgrid chips. These chips were air-dried (no dehydration or critical point drying) and washed with deionized water to remove salts in the culture medium.

Conducting probe atomic force measurements.

An Au microgrid (Fig. 3) was electrically connected to the sample stage of an AFM system (Veeco Dimension V) using silver paint. Pt/Cr coated Si AFM probes (BudgetSensors ContE) with a nominal spring constant of 0.2 N/m were used for both tapping and contact mode imaging. The current vs. voltage (I-V) curves of Fig. 3 were measured in point-spectroscopy mode with a typical gain setting of 1 V/nA. The loading force applied for electrical measurements (Fig. 3) was 4 nN, which we found to be the minimum force required to establish a stable short-circuiting contact between the conductive AFM tip and the Au electrode. In many cases, an imaging force of 10 nN or greater began to dislocate and damage the biological structures. Under such conditions, the apex of the conductive AFM tip could be coated with insulating debris. The minimum force (4 nN) was chosen for the electrical measurements to maintain an intimate electrical contact and not to damage the delicate nanowires. The sample voltage was ramped between −1 and 1 V at 0.2 Hz, yielding consistent and repeatable data. The resistance at each position along the nanowire was calculated using the most linear part (±0.4 V) of the I-V curve.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Zhou's research group and S. Cabrini for experimental help. Nanofabrication was conducted at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Molecular Foundry, University of California Riverside Center for Nanoscale Science and Engineering, and the Western Nanofabrication Laboratory. This work was supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research MURI FA9550-06-1-0292 and YIP FA9550-10-1-0144. Work at the Molecular Foundry was supported by the Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the US Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC02-05CH11231. This research was partially supported through a grant from the Legler-Benbough Foundation (San Diego, CA), internal funding from the J. Craig Venter Institute, and by the Canadian Natural Science and Engineering Research Council, Interdisciplinary Development Initiatives Program, Canada Foundation for Innovation, and Surface Science Western.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1004880107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Chang IS, et al. Electrochemically active bacteria (EAB) and mediator-less microbial fuel cells. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;16:163–177. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lovley DR, Coates JD, Blunt-Harris EL, Phillips EJP, Woodward JC. Humic substances as electron acceptors for microbial respiration. Nature. 1996;382:445–448. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newman DK, Kolter R. A role for excreted quinones in extracellular electron transfer. Nature. 2000;405:94–97. doi: 10.1038/35011098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marsili E, et al. Shewanella secretes flavins that mediate extracellular electron transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3968–3973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710525105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Canstein H, Ogawa J, Shimizu S, Lloyd JR. Secretion of flavins by Shewanella species and their role in extracellular electron transfer. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:615–623. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01387-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myers CR, Myers JM. Localization of cytochromes to the outer membrane of anaerobically grown Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3429–3438. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.11.3429-3438.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reguera G, et al. Extracellular electron transfer via microbial nanowires. Nature. 2005;435:1098–1101. doi: 10.1038/nature03661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorby YA, et al. Electrically conductive bacterial nanowires produced by Shewanella oneidensis strain MR-1 and other microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11358–11363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604517103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Naggar MY, Gorby YA, Xia W, Nealson KH. The molecular density of states in bacterial nanowires. Biophys J. 2008;95:L10–L12. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.134411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reguera G, et al. Biofilm and nanowire production leads to increased current in Geobacter sulfurreducens fuel cells. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:7345–7348. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01444-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu JY, Chung SW, Heath JR. Silicon nanowires: Preparation, device fabrication, and transport properties. J Phys Chem B. 2000;104:11864–11870. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen H, Nogues C, Naaman R, Porath D. Direct measurement of electrical transport through single DNA molecules of complex sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11589–11593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505272102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andolfi L, Cannistraro S. Conductive atomic force microscopy study of plastocyanin molecules adsorbed on gold electrode. Surf Sci. 2005;598:68–77. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai LT, Tabata H, Kawai T. Probing electrical properties of oriented DNA by conducting atomic force microscopy. Nanotechnology. 2001;12:211–216. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLean JS, et al. Quantification of electron transfer rates to a solid phase electron acceptor through the stages of biofilm formation from single cells to multicellular communities. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44:2721–2727. doi: 10.1021/es903043p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.