Abstract

In mammalian testes, the blood–testis barrier (BTB) or Sertoli cell barrier created by specialized junctions between Sertoli cells near the basement membrane confers an immunological barrier by sequestering the events of meiotic division and postmeiotic germ cell development from the systemic circulation. The BTB is constituted by coexisting tight junctions (TJs), basal ectoplasmic specializations, desmosomes, and gap junctions. Despite being one of the tightest blood–tissue barriers, the BTB has to restructure cyclically during spermatogenesis. A recent study showed that gap junction protein connexin 43 (Cx43) and desmosome protein plakophilin-2 are working synergistically to modulate the BTB integrity by regulating the distribution of TJ-associated proteins at the Sertoli–Sertoli cell interface. However, the precise role of Cx43 in regulating the cyclical restructuring of junctions remains obscure. In this report, the calcium switch and the bisphenol A (BPA) models were used to induce junction restructuring in primary cultures of Sertoli cells isolated from rat testes that formed a TJ-permeability barrier that mimicked the BTB in vivo. The removal of calcium by EGTA perturbed the Sertoli cell tight junction barrier, but calcium repletion allowed the “resealing” of the disrupted barrier. However, a knockdown of Cx43 in Sertoli cells by RNAi significantly reduced the kinetics of TJ-barrier resealing. These observations were confirmed using the bisphenol A model in which the knockdown of Cx43 by RNAi also perturbed the TJ-barrier reassembly following BPA removal. In summary, Cx43 is crucial for TJ reassembly at the BTB during its cyclic restructuring throughout the seminiferous epithelial cycle of spermatogenesis.

Keywords: bisphenol A, calcium switch, gap junction, seminiferous epithelial cycle, spermatogenesis

In mammalian testes, the blood–testis barrier (BTB) segregates the epithelium of seminiferous tubules into apical and basal compartments (1, 2). Unlike other blood–tissue barriers (e.g., blood–brain barrier, blood–retina barrier) that are constituted by tight junctions (TJs) between endothelial cells of the microvessels at the apical region, the BTB is created by adjacent Sertoli cells in the seminiferous epithelium near the basement membrane. The BTB is constituted by coexisting TJs, basal ectoplasmic specialization (basal ES, a testis-specific adherens junction type), desmosome-like junction (or desmosome-gap junction), and gap junction (GJ) (1–3). Whereas the BTB is one of the tightest blood–tissue barriers, it undergoes cyclical restructuring to accommodate the transit of preleptotene spermatocytes from the basal to the apical compartment during spermatogenesis, so that meiotic divisions and postmeiotic germ cell development (i.e., spermiogenesis) can take place in the apical compartment of the seminiferous epithelium behind this immunological barrier. The immunological barrier conferred by the BTB cannot be compromised, even transiently, during the transit of preleptotene spermatocytes to avoid the production of anti-sperm antibodies and to maintain the immune privilege status of the testis (1). Recent studies suggest that this can be accomplished by first assembling “new” TJ fibrils behind the transiting preleptotene spermatocytes, likely induced by testosterone before the disruption of TJ fibrils above the spermatocytes regulated by cytokines, such as TGF-β3 and TNFα (2). However, the mechanism(s) that coordinate these events of junction assembly and disassembly at the BTB remain obscure.

GJ is known to facilitate intercellular communication via GJ channels (connexons coupled between two cells) or communication with the extracellular space via hemichannels (uncoupled connexons) and participate in the regulation of various physiological processes, such as differentiation and apoptosis (4, 5). GJ at the BTB was speculated to be crucial to regulate the cyclic restructuring of BTB during spermatogenesis (6). An earlier study showed that connexin 43 (Cx43), a predominant GJ protein in the testis (5), is not necessary for the maintenance of the BTB integrity. A knockdown of Cx43 alone by RNAi using specific Cx43 siRNA duplexes in a Sertoli cell epithelium with an established TJ-permeability barrier did not affect the barrier integrity unless with a knockdown of both Cx43 and desmosomal protein plakophilin-2 (7). However, it is unknown if Cx43 is involved in regulating the homeostasis of BTB, such as junction restructuring during the transit of preleptotene spermatocytes across the immunological barrier. In the present study, we examined the involvement of Cx43 in the reassembly of the Sertoli cell TJ barrier by using two different models, namely the calcium switch model (8) and the bisphenol A (BPA) model (9). These findings report the critical role of Cx43-based GJ in the homeostasis of the BTB during spermatogenesis.

Results

Cx43 Is Crucial for the Reassembly of the Disrupted Sertoli Cell TJ-Permeability Barrier: A Study Using the Calcium Switch Model.

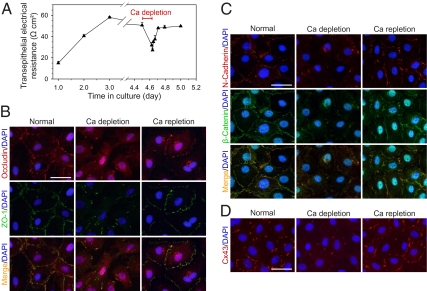

The calcium switch model was used to study the role of Cx43 in the homeostasis of BTB, in particular its involvement in junction reassembly at the BTB. An in vitro system using primary Sertoli cells was used for this study because the Sertoli cell epithelium in vitro could establish a functional TJ-permeability barrier that mimics the BTB in vivo, including the ultrastructural features of TJ, basal ES, and desmosome (10). Analogous to MDCK cells, a depletion or replenishment of [Ca2+] in the spent media of the bicameral units or dishes with an intact Sertoli cell epithelium induced rapid disassembly or reassembly of the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier (Fig. 1). [Ca2+] depletion using 4 mM EGTA led to a rapid decline in the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier (Fig. 1A). This was concomitant with a redistribution of junction proteins, moving away from the cell–cell interface to cell cytosol, including TJ proteins occludin and ZO-1 (Fig. 1B), basal ES protein N-cadherin and β-catenin (Fig. 1C), Cx43 (Fig. 1D), and desmosome protein plakophilin-2 (Fig. S1A) as demonstrated by dual-labeled immunofluorescence analysis using the corresponding specific antibodies (Table S1). Upon removal of the calcium chelator and replenishing [Ca2+] in the media (calcium repletion), reassembly of junctions was demonstrated by the increase in the transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) across the cell epithelium (Fig. 1A) and relocalization of junction proteins back to the cell surface (Fig. 1 B–D). During calcium depletion, changes in protein levels of occludin, ZO-1, and plakophilin-2 were insignificant except for Cx43 (Fig. S1B).

Fig. 1.

Disruption of the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier and its reassembly in the calcium switch model. (A) A disruption in the Sertoli cell TJ-barrier integrity was detected when [Ca2+] in the culture medium of the bicameral units was depleted with 4 mM EGTA for 3 h. The removal of the calcium chelator and calcium repletion allows the “resealing” of the disrupted TJ-permeability barrier. (B–D) The localizations of tight junction markers occludin and ZO-1, basal ES markers N-cadherin and β-catenin, and Cx43 were studied by dual-labeled immunofluorescence analysis during the calcium switch. In Sertoli cells depleted of the calcium ion for 3 h, junction proteins moved away from the cell–cell interface when compared with the untreated cells. After calcium repletion for 4–5 h, redistribution of junction proteins back to the cell surface was observed. This observation illustrates that the Sertoli cell BTB integrity and cell junctions can be rapidly disrupted and resealed using the calcium switch model. (Scale bars, 40 μm.)

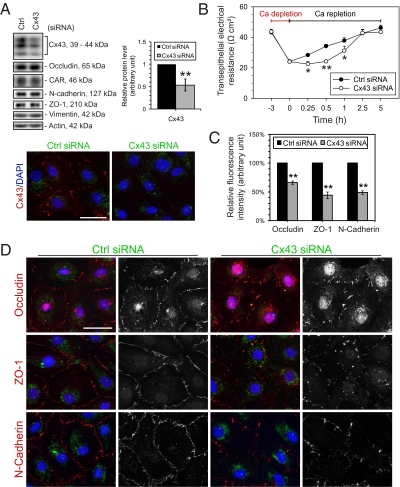

Cells transfected with Cx43 siRNA duplexes showed a specific knockdown of Cx43 level by ∼50% whereas other BTB proteins including occludin, CAR, N-cadherin, and ZO-1 remained unchanged (Fig. 2A). When calcium switch was performed on Sertoli cells transfected with nontargeting control or Cx43-specific siRNA duplexes, a difference in junction reassembly was observed between these two groups during the calcium repletion period (Fig. 2B). Sertoli cells with a knockdown of Cx43 showed a significant delay in TJ-permeability barrier reassembly during calcium repletion when compared with cells transfected with nontargeting control siRNA duplexes. Immunofluorescence studies also indicated a reduction of 35–55% of occludin, ZO-1, and N-cadherin at the cell surface during calcium repletion in cells with a knockdown of Cx43 (Fig. 2 C and D) as a result of changes in protein redistribution even though the steady-state levels of these marker proteins showed no significant differences (Fig. S1C).

Fig. 2.

The loss of Cx43 at the BTB by RNAi hinders junction reassembly after calcium repletion. Sertoli cells freshly isolated from 20-day-old rat testes were cultured for 3 d, forming an intact epithelium with an established functional TJ-permeability barrier when assessed by transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) across the cell epithelium; and ultrastructures of TJ, basal ES and desmosome-like junction were also detected when examined by electron microscopy. Thus, the Sertoli cell epithelium used for this experiment mimicked the BTB in vivo. Thereafter, cells were transfected with 50–80 nM of nontargeting control (Ctrl) siRNA duplexes or Cx43 siRNA duplexes for 24 h. Calcium switch was performed ∼1.5 d after the transfection. (A) There was a 50% knockdown of Cx43 in cells transfected with Cx43 siRNA duplexes ∼2 d posttransfection. The levels of occludin, CAR, N-cadherin, and ZO-1 remained unchanged, illustrating the specificity of this RNAi experiment and that there was no off-target effect following the silencing of Cx43 in the Sertoli cell epithelium. The fluorescence micrographs shown in the bottom panel in (A) also support findings of the immunoblot analysis shown in the upper panel since there was a considerable loss of Cx43 at the cell-cell interface after the knockdown of Cx43 by RNAi. (B) After calcium repletion, Sertoli cell epithelium transfected with Cx43 siRNA duplexes displayed a significantly slower rebound of the disrupted TJ barrier when compared with cells transfected with non-targeting Ctrl siRNA duplexes. (C and D) Approximately 5 h after calcium ion repletion, Sertoli cells transfected with siRNA duplexes were fixed for dual-labeled immunofluorescence analysis to investigate the localization of occludin, ZO-1, and N-cadherin. In Sertoli cells with a knockdown of Cx43, considerably fewer junction proteins were found at the cell–cell interface, illustrating a disruption in the kinetics of junction reassembly in Sertoli cells with a knockdown of Cx43. Micrographs in the second and fourth columns in D are the corresponding grayscale images of the true-color images on the left, in order to better depict changes in protein localization. A representative dataset from 4 independent experiments is shown. (Scale bar, 40 μm.) *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; statistical difference from the Ctrl group was tested using Student's t test in A and C and ANOVA analysis with posthoc two-tailed Dunnett's test in B.

BPA Induces Reversible Disruption of the Sertoli Cell TJ-Permeability Barrier.

A previous report from our laboratory demonstrated that BPA causes a transient disruption of the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier (9), similar to the result shown in Fig. 3A. However, it is not known if BTB-associated proteins recover in parallel to the “resealing” of the disrupted TJ barrier. Changes in the steady-state levels of junction proteins at the BTB were thus assessed at 0, 8, and 24 h following removal of the BPA during the TJ-barrier resealing and compared with controls (Fig. 3). The regimen for this experiment is illustrated in Fig. 3B. Cells were incubated with 200 μM BPA for 24 h to induce junction disruption. Thereafter, cells were washed to remove BPA, which was designated as time 0, and then incubated in fresh F12/DMEM to allow for junction reassembly. Cell cultures were terminated at 0, 8, and 24 h to assess changes in protein levels. At 0 h after removal of BPA, the disruptive effects on the Sertoli cell TJ barrier were assessed. There was a decline in junction integrity (Fig. 3A) and protein levels of various markers associated with TJ (occludin and JAM-A), basal ES (N-cadherin, α-catenin, and β-catenin) and desmosome-gap junction (desmoglein-2), except CAR and plakophilin-2 (Fig. 3 C and D). By 8 h after removal of BPA, the TJ-barrier integrity had rebounded, making it similar to the vehicle control group (Fig. 3A). The levels of many BTB proteins (e.g., JAM-A, N-cadherin, and desmoglein-2) were recovering (Fig. 3 C and D). At 24 h, most junction protein levels (e.g., JAM-A, N-cadherin, desmoglein-2, and β-catenin) had recovered (Fig. 3 C and D).

Fig. 3.

Bisphenol A (BPA) causes a transient disruption of the BTB integrity and changes in the steady-state levels of proteins at the BTB in primary Sertoli cell cultures. (A) In the TER experiment, Sertoli cells were treated with vehicle control (0.1% ethanol, V Ctrl) or BPA (200 μM) on day 3 of culture. BPA-treated Sertoli cells displayed a drastic reduction of the TJ-permeability barrier from 8 h posttreatment onward, when compared with the V Ctrl. In one treatment group, BPA was removed from the Sertoli cell epithelium after 24 h treatment to allow the “resealing” of the disrupted TJ barrier. A representative dataset is shown (n = 4). (B–D) SCs were treated with V Ctrl or BPA for 24 h. In the BPA treatment group, BPA was removed after 24 h and cells were rinsed and replenished with normal culture medium. Cell lysates were collected 0, 8, and 24 h after BPA removal to analyze changes in the protein levels of various junction markers of TJ, basal ES and desmosome-like junction. The cytoskeletal protein levels, namely vimentin and actin, serve as loading control. Representative immunoblots are shown in C, where n = 3–5. The densitometry results are summarized in D. The BPA-treated group from each time point was normalized and compared against the V Ctrl group of the corresponding time point. Protein levels of the BPA-treated group were also compared at different times after BPA removal to assess the degree of recovery. At 0 h after BPA removal, the disruptive effect of BPA on junction protein level was observed for integral membrane proteins of TJ (occludin and JAM-A), basal ES (N-cadherin) and desmosome-like junction (desmoglein-2), and basal ES adaptors (α- and β-catenins). Junction proteins, including JAM-A, N-cadherin, desmoglein-2, and β-catenin, show a significant rebound from the lowered protein level after BPA removal. These data thus illustrate the reversible effect of BPA on junction integrity and junction protein levels. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; statistical difference from the V Ctrl group was tested using ANOVA analysis with a posthoc Tukey/Kramer test.

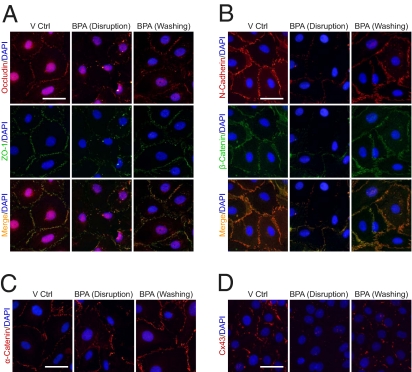

These findings were supported by fluorescence staining of selected BTB-associated proteins in the Sertoli cell epithelium (Fig. 4 and Fig. S1A). Occludin, ZO-1 (Fig. 4A), N-cadherin, β-catenin (Fig. 4B), α-catenin (Fig. 4C), Cx43 (Fig. 4D), and plakophilin-2 (Fig. S1A) were detected at the cell–cell interface in the vehicle control group. After 24 h treatment in BPA, considerably fewer proteins were detected at the cell–cell interface. When cells were incubated in normal medium for 24 h, these junction proteins became relocalized back to the cell surface, illustrating a recovery from BPA-induced junction disruption. Whereas the steady-state level of occludin in the Sertoli cell epithelium failed to rebound to the control level after the removal of BPA (Fig. 3 C and D), the majority of occludin relocated back to the cell–cell interface following BPA removal (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Changes in the distribution of junction proteins following treatment of Sertoli cell epithelium with BPA. The distribution of occludin/ZO-1 (A), N-cadherin/β-catenin (B), α-catenin (C), and Cx43 (D) in SCs was studied after the treatment and removal of BPA. During BPA treatment, fewer junction proteins were observed at the cell–cell interface. After BPA removal, reappearance of these junction proteins was observed at the cell–cell interface. These data again illustrate the reversibility of junction disruption induced by BPA. (Scale bars, 40 μm.)

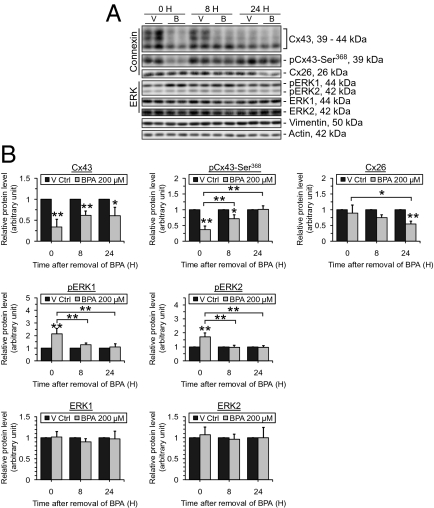

BPA treatment for 24 h was shown to cause a drastic decline in the steady-state levels of Cx43 and its phosphorylated inhibitory form at Ser368 (time 0 column, Fig. 5). After 1–2 h BPA treatment, gap junction communication in Sertoli cells was significantly reduced as shown in a dye transfer assay (Fig. 6). At 8 h and 24 h after removal of BPA, a recovery of Cx43 p-Ser368, but not Cx43, was noted (Fig. 5). Cx26 level on the other hand was not affected by BPA treatment but a decline in its level was detected at 24 h after BPA removal. This result illustrates differential responses of connexins toward BPA treatment and likely suggests the differential roles of connexins in the regulation of junction restructuring at the BTB. In addition, the ERK signaling pathway was induced during BPA treatment but the pERK1/2 level quickly returned to its basal level by 8 and 24 h after BPA removal. These results suggest that the ERK signaling pathway probably participated in the junction disruption induced by BPA but not the junction reassembly after BPA removal.

Fig. 5.

Changes in the steady-state protein levels of connexins and ERK following treatment of Sertoli cells with BPA and its removal. Sertoli cells cultured at 0.5 × 106 cells/cm2 on Matrigel-coated multiwell plates were treated with BPA as depicted in Fig 3B. Cx43 and its phosphorylated form pCx43-Ser368 show a drastic reduction in protein levels after 24 h BPA treatment but only pCx43-Ser368 shows a significant recovery from the reduction at 8 h after BPA removal (B). The protein level of Cx26 remains unchanged by BPA treatment. Its level was lowered at 24 h after BPA removal when other junction proteins recover, displaying the differential effect of BPA on connexins expressed by Sertoli cells. The ERK signaling pathway was induced during BPA treatment but quickly went back to its normal level after BPA removal. Representative immunoblots are shown in A, where n = 3–4. The densitometry of the junction proteins is analyzed and summarized in B. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; statistical difference from the Ctrl group was tested using ANOVA analysis with a posthoc Tukey/Kramer test.

Fig. 6.

A dye transfer assay to study the gap junction communication after BPA treatment. Freshly isolated Sertoli cells from 20-d-old rat testes were cultured at 0.15 × 106 cells/cm2 on Matrigel-coated glass-bottom dishes for 2 d before their use for this assay. Cells were labeled with calcein AM and then treated with 0.1% ethanol (V Ctrl) or 200 μM BPA for 1–2 h. The dye transfer assay, as described in Materials and Methods, involves photobleaching of a single Sertoli cell and then tracking the transfer of calcein into the photobleached cell (fluorescence recovery) to assess the degree of gap junction communication. At 150 s after photobleaching, Sertoli cells treated with BPA display a lower fluorescence recovery. These data illustrate that BPA can disrupt the gap junction communication in Sertoli cells after 1–2 h treatment. The result reported herein is representative of data from three independent experiments with similar findings. *P < 0.001.

A Knockdown of Cx43 by RNAi Disrupts the Sertoli Cell TJ-Permeability Barrier Recovery After Removal of BPA.

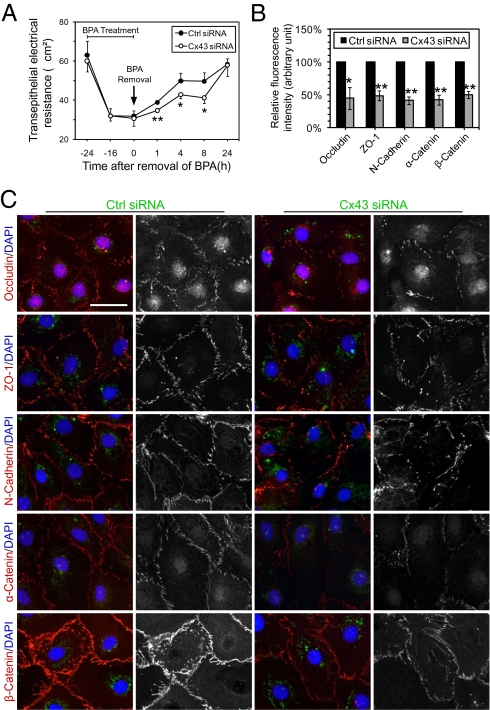

After ∼1.5 d of transfection of Sertoli cells with either nontargeting control or Cx43 siRNA duplexes, cells were treated with 200 μM BPA for 24 h to induce junction restructuring. After BPA removal, the Sertoli cell TJ barrier began to reseal in both groups transfected with control or Cx43 siRNA duplexes, but a slower rate of recovery was detected in the latter group (Fig. 7A). The findings reported in Fig. 7A were confirmed in immunofluorescence studies shown in Fig. 7 B and C. It was noted that proteins at the Sertoli–Sertoli cell interface, including occludin, N-cadherin, ZO-1, α-catenin, and β-catenin, relocalized back to the cell surface after 24 h of BPA removal in the control silencing group. However, cells with a knockdown of Cx43 displayed a reduced relocalization of these junction proteins to the cell–cell interface by ∼50–60% (Fig. 7 B and C), with protein levels of these proteins showing no significant differences from the control group (Fig. S1D). These data thus illustrate that a knockdown of Cx43 would impair the reassembly of a disrupted TJ barrier in the Sertoli cell epithelium induced by BPA, consistent with findings using the calcium switch model.

Fig. 7.

A study using the BPA model to examine the role of Cx43 in TJ-permeability barrier reassembly in Sertoli cell epithelium. After ≈1.5 d posttransfection with Ctrl or Cx43 siRNA duplexes, cells were treated with 200 μM BPA for 24 h to induce junction restructuring. (A) Upon BPA removal, the resealing of the disrupted TJ-permeability barrier occurred in cells transfected with either nontargeting control or Cx43 siRNA duplexes, but at a significantly slower rate in cells with a Cx43 knockdown. (B and C) Changes in the distribution of proteins at the Sertoli–Sertoli cell interface were examined by immunofluorescence microscopy. Junction proteins, including occludin, N-cadherin, ZO-1, α-catenin, and β-catenin, relocalized back to the cell surface after 24 h of BPA removal in the control silencing group. However, cells with a knockdown of Cx43 displayed a disrupted relocalization of these junction proteins back to the cell–cell interface. These data illustrate that the knockdown of Cx43 impaired junction reassembly after BPA-induced Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier disruption. Micrographs in the second and fourth columns in C are the corresponding grayscale images of the true-color images on the left, in order to better depict changes in protein localization. Representative data from four independent experiments are shown. (Scale bar, 40 μm.)

Discussion

Cx43 is one of the best studied GJ proteins in the testis (5). It is mostly localized at the BTB and was suggested to modulate BTB dynamics during spermatogenesis (11, 12). A recent report from our laboratory showed that Cx43 alone is not necessary for the maintenance of the BTB integrity (7) because its knockdown by RNAi failed to perturb the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier. However, a simultaneous knockdown of Cx43 and plakophilin-2 by RNAi would perturb the Sertoli cell TJ-barrier function (7), illustrating Cx43 and plakophilin-2 as a functional complex to maintain the integrity of the BTB. Herein, Cx43 was shown to be critical for TJ reassembly at the Sertoli cell BTB after its disruption induced by either calcium depletion using divalent ion chelator EGTA or exposure of the Sertoli cell epithelium to BPA.

Using the calcium switch model, it was shown that a knockdown of Cx43 in Sertoli cells disrupted the junction recovery process during calcium repletion. Cx43 has been shown to mediate calcium signaling by directly transporting the calcium ion across connexons (coupled as gap junction channels or uncoupled as hemichannels) (13–15). Blockage of Cx43 channels and hemichannels with Cx43-specific antibodies or mimetic peptides resulted in a decline in the propagation of the calcium wave (13, 14, 16). Also Cx43 was shown to interact with calmodulin, a calcium binding protein and an important modulator in the calcium signaling pathway (17). Hence the above observations may be attributed to the ability of calcium transduction between Sertoli cells mediated by Cx43. The decline of Cx43 after its knockdown by RNAi may reduce the ability of the disrupted Sertoli cell TJ barrier to reassemble because calcium trafficking across the Cx43-based GJ channels was interrupted.

To further validate the involvement of Cx43 in junction reassembly at the Sertoli cell BTB, we used another model to induce junction restructuring. The findings in the Sertoli cell TJ-barrier recovery after BPA-induced disruption were consistent with results of the calcium switch model. The knockdown of Cx43 in Sertoli cells by RNAi also significantly delayed the resealing/reassembly after the BPA-induced TJ-barrier disruption. In short, the knockdown of Cx43 hinders the rate of junction reassembly as demonstrated in both study models. However, it is of interest to note that the TER readings in both calcium switch and BPA-treated groups transfected with nontargeting control and Cx43 siRNA displayed no statistical difference by 2.5 or 24 h, respectively, after junction reassembly began. This result thus suggests that the role of Cx43 in junction reassembly at the BTB could be compensated perhaps by other connexins or the remaining Cx43 still present in Sertoli cells. Nonetheless, these findings illustrate that Cx43 is crucial to elicit proper junction reassembly during BTB restructuring throughout spermatogenesis such as at stage VIII–IX of the epithelial cycle.

These findings are also supported by the phenotypes observed in mice and humans with lower levels of Cx43. Adult Sertoli cell-specific Cx43 knockout (SC-Cx43 KO) mice displayed spermatogenic arrest at the spermatogonial level (18, 19). Sertoli cells were found to undergo mitotic proliferation without differentiation and sloughing of Sertoli cell clusters can be found at the lumen of the seminiferous tubule (18). In humans, testes with Sertoli cell only syndrome or spermatogenic arrest at the spermatogonial level in infertile men were also correlated with lower levels of Cx43 in seminiferous tubules (20, 21). Adult male rats with neonatal exposure to BPA had a lowered level of Cx43 and a smaller litter size, reduced sperm count, and poor sperm motility despite an increase in localization of immunoreactive N-cadherin and ZO-1 near the BTB region (22). Because maturation of spermatogenesis requires the establishment of BTB along with differentiation of Sertoli cells, normal spermatogenesis cannot take place in the absence of a functional BTB. A malfunctioning BTB thus leads to infertility or reduced fertility in rodents and humans (18, 20–22). This postulate is further supported by the findings in claudin-11−/− mice (claudin-11 is an integral membrane protein at the BTB) wherein Sertoli cells in claudin-11−/− mice are similarly found to be proliferating and sloughed off into the lumen (23). Despite the expression of other TJ proteins being unaffected or even elevated, Sertoli cells in claudin-11−/− mice failed to differentiate and establish TJ strands (23, 24), leading to a disrupted BTB. According to the positive role of Cx43 in BTB reassembly during BTB restructuring as shown in this study, the loss of Cx43 in SC-Cx43 KO mice may lead to a malfunctioned BTB and hence disruption of spermatogenesis.

The assembly of the adherens junction (AJ) and the GJ in different epithelia was shown to be interdependent (25). The formation of both the AJ and the GJ can be blocked with the use of antibodies against either N-cadherin or Cx43 (26), and Cx43 can be transported directly to existing AJ sites through microtubules (27). Cx43 has also been reported to promote endothelial attachment of leukocytes induced by cytokines or tumor cells during metastasis when it was overexpressed (28–30). These reports thus illustrate an intimate functional relationship between AJ and GJ. It is hence not surprising that the reassembly of basal ES was impaired in Sertoli cells with a knockdown of Cx43. However, the involvement of Cx43 in TJ assembly or reassembly is less clear in these earlier studies. We provide herein a demonstration that Cx43 regulates BTB dynamics via its effects on the reassembly of TJs apart from basal ES at the BTB.

It is of interest to note that the GJ also works in conjunction with the desmosome during spermatogenesis to provide the necessary crosstalk between various junction types at the BTB. A recent study showed that apart from TJs and basal ES, the desmosome is crucial to maintain the integrity of the Sertoli cell TJ-barrier at the BTB (31). A simultaneous knockdown of desmosome integral membrane proteins desmoglein-2 and desmocollin-2 by RNAi disrupted the Sertoli cell-permeability barrier and affected protein distribution of ZO-1 and CAR at the Sertoli–Sertoli cell interface (31). Furthermore, as discussed above, simultaneous knockdown of Cx43 and plakophilin-2 (a desmosome protein) perturbed the TJ-permeability barrier (7). These earlier findings and the results reported herein thus suggest that Cx43 may be responsible for the necessary crosstalk between different junction complexes to maintain their adhesive function and to coordinate different junctions to maintain the immunological barrier integrity during the transit of preleptotene spermatocytes at the BTB (see SI Discussion for additional discussion).

Materials and Methods

Transfection of Cx43 siRNA.

Sertoli cells cultured at 0.045–1.0 × 106 cells/cm2 were transfected with siRNA duplexes including ON-TARGETplus nontargeting siCONTROL pool (D-001810-10), siRNA pool specifically targeting Cx43 (J-100614-09, -10, and -11), or siGLO green transfection indicator (D-001630-01) (Dharmacon and Thermo Fisher Scientific), at a total concentration of 35–80 nM using 4–12 μL RiboJuice siRNA transfection reagent (Novagen, EMD Biosciences) in a final reaction volume of 0.5–1 mL on day 3 when an intact cell epithelium was established (7). After a 24-h incubation with the transfection mixture, cells were rinsed in culture medium and replenished with fresh DMEM/F12 with growth factors. In selected experiments where Sertoli cells were plated on bicameral units, the TJ barrier across the cell epithelium was monitored by TER.

Calcium Switch.

Calcium switch was performed as described (8). After a 1-h starvation in plain DMEM/F12, cells were incubated for 3 h in DMEM/F12 containing growth factors and 4 mM EGTA to chelate calcium ions. After this brief incubation, cells were rinsed twice and were replenished with normal DMEM/F12 with Ca2+ and appropriate growth factors. Different termination time points were used in the measurement of TER and cell staining (Figs. 1 and 2) as demonstrated in preliminary studies that Sertoli cells cultured at lower cell density would take a longer time to reassemble junctions after calcium repletion.

BPA Treatment.

Sertoli cells were incubated in 200 μM BPA for 24 h to induce junction disruption (9). In the vehicle control group, cells were treated with 0.1% ethanol. After incubation, cells were washed and replenished with normal nutrient medium to allow the resealing of the disrupted Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier. For cells transfected with nontargeting control or Cx43 siRNA duplexes, cells were treated with BPA on 1.5 d posttransfection.

Dye Transfer Assay.

Sertoli cells cultured at 0.15 × 106 cells/cm2 for 2 d on a Matrigel-coated glass-bottom dish were used for fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) analysis of calcein transfer (further details in SI Materials and Methods). This assay assesses the degree of gap junction communication by the intercellular transfer of calcein (32). Cells were labeled with 5 μM calcein acetoxymethyl ester (AM) for 30 min at 35 °C. For each FRAP analysis, a single cell was photobleached selectively at 488 nm and 5 prebleach photos and 75 postbleach photos were acquired at 2 ms intervals. Cells were treated with DMEM/F12 containing either 0.1% ethanol or 200 μM BPA for 1–2 h. For each treatment group in a single dye-coupling assay, FRAP was performed on at least 15 different cells.

General Methods.

Further information on Sertoli cell cultures, lysate preparation, immunoblot analysis, fluorescence microscopy, dual-labeled immunofluorescence analysis, statistical analysis, and FRAP can be found in SI Materials and Methods and Table S1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Alison North (The Rockefeller University Bio-Imaging Resource Center) for technical support in the FRAP study. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health [National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Grants R01 HD056034 (to C.Y.C.) and U54 HD029990 Project 5 (to C.Y.C.)]; and Hong Kong Research Grants Council, Grant HKU7693/07M (to W.M.L.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1007047107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cheng CY, Mruk DD. Cell junction dynamics in the testis: Sertoli-germ cell interactions and male contraceptive development. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:825–874. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00009.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng CY, Mruk DD. A local autocrine axis in the testes that regulate spermatogenesis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2010;6:380–395. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2010.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogl AW, Vaid KS, Guttman JA. The Sertoli cell cytoskeleton. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;636:186–211. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09597-4_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dbouk HA, Mroue RM, El-Sabban ME, Talhouk RS. Connexins: A myriad of functions extending beyond assembly of gap junction channels. Cell Commun Signal. 2009;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pointis G, Gilleron J, Carette D, Segretain D. Physiological and physiopathological aspects of connexins and communicating gap junctions in spermatogenesis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2010;365:1607–1620. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russell LD. Movement of spermatocytes from the basal to the adluminal compartment of the rat testis. Am J Anat. 1977;148:313–328. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001480303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li MWM, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Connexin 43 and plakophilin-2 as a protein complex that regulates blood-testis barrier dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:10213–10218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901700106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kartenbeck J, Schmelz M, Franke WW, Geiger B. Endocytosis of junctional cadherins in bovine kidney epithelial (MDBK) cells cultured in low Ca2+ ion medium. J Cell Biol. 1991;113:881–892. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.4.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li MWM, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Disruption of the blood-testis barrier integrity by bisphenol A in vitro: Is this a suitable model for studying blood-testis barrier dynamics? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:2302–2314. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siu MKY, Wong CH, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Sertoli-germ cell anchoring junction dynamics in the testis are regulated by an interplay of lipid and protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25029–25047. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501049200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Risley MS, Tan IP, Roy C, Sáez JC. Cell-, age- and stage-dependent distribution of connexin43 gap junctions in testes. J Cell Sci. 1992;103:81–96. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pelletier RM. The distribution of connexin 43 is associated with the germ cell differentiation and with the modulation of the Sertoli cell junctional barrier in continual (guinea pig) and seasonal breeders’ (mink) testes. J Androl. 1995;16:400–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boitano S, Dirksen ER, Evans WH. Sequence-specific antibodies to connexins block intercellular calcium signaling through gap junctions. Cell Calcium. 1998;23:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(98)90069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verma V, Hallett MB, Leybaert L, Martin PE, Evans WH. Perturbing plasma membrane hemichannels attenuates calcium signalling in cardiac cells and HeLa cells expressing connexins. Eur J Cell Biol. 2009;88:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paemeleire K, et al. Intercellular calcium waves in HeLa cells expressing GFP-labeled connexin 43, 32, or 26. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:1815–1827. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.5.1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boitano S, Evans WH. Connexin mimetic peptides reversibly inhibit Ca(2+) signaling through gap junctions in airway cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L623–L630. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.4.L623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou Y, et al. Identification of the calmodulin binding domain of connexin 43. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35005–35017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707728200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brehm R, et al. A sertoli cell-specific knockout of connexin43 prevents initiation of spermatogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:19–31. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sridharan S, et al. Proliferation of adult sertoli cells following conditional knockout of the Gap junctional protein GJA1 (connexin 43) in mice. Biol Reprod. 2007;76:804–812. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.059212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steger K, Tetens F, Bergmann M. Expression of connexin 43 in human testis. Histochem Cell Biol. 1999;112:215–220. doi: 10.1007/s004180050409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuo Y, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of connexin43 expression in infertile human testes. Acta Histochem Cytochem. 2007;40:69–75. doi: 10.1267/ahc.07001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salian S, Doshi T, Vanage G. Neonatal exposure of male rats to Bisphenol A impairs fertility and expression of sertoli cell junctional proteins in the testis. Toxicology. 2009;265:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mazaud-Guittot S, et al. Claudin 11 deficiency in mice results in loss of the Sertoli cell epithelial phenotype in the testis. Biol Reprod. 2010;82:202–213. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.078907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gow A, et al. CNS myelin and sertoli cell tight junction strands are absent in Osp/claudin-11 null mice. Cell. 1999;99:649–659. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81553-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Derangeon M, Spray DC, Bourmeyster N, Sarrouilhe D, Hervé JC. Reciprocal influence of connexins and apical junction proteins on their expressions and functions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:768–778. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer RA, Laird DW, Revel J-P, Johnson RG. Inhibition of gap junction and adherens junction assembly by connexin and A-CAM antibodies. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:179–189. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.1.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaw RM, et al. Microtubule plus-end-tracking proteins target gap junctions directly from the cell interior to adherens junctions. Cell. 2007;128:547–560. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eugenín EA, Brañes MC, Berman JW, Sáez JC. TNF-α plus IFN-γ induce connexin43 expression and formation of gap junctions between human monocytes/macrophages that enhance physiological responses. J Immunol. 2003;170:1320–1328. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin JHC, et al. Connexin 43 enhances the adhesivity and mediates the invasion of malignant glioma cells. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4302–4311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04302.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Véliz LP, González FG, Duling BR, Sáez JC, Boric MP. Functional role of gap junctions in cytokine-induced leukocyte adhesion to endothelium in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H1056–H1066. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00266.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lie PPY, Cheng CY, Mruk DD. Crosstalk between desmoglein-2/desmocollin-2/Src kinase and coxsackie and adenovirus receptor/ZO-1 protein complexes, regulates blood-testis barrier dynamics. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:975–986. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilleron J, et al. A potential novel mechanism involving connexin 43 gap junction for control of sertoli cell proliferation by thyroid hormones. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:153–161. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.