Abstract

The Problem Solving Intervention (PSI) is a structured, cognitive–behavioral intervention that provides people with problem-solving coping skills to help them face major negative life events and daily challenges. PSI has been applied to numerous settings but remains largely unexplored in the hospice setting. The aim of this pilot study was to demonstrate the feasibility of PSI targeting informal caregivers of hospice patients. We enrolled hospice caregivers who were receiving outpatient services from two hospice agencies. The intervention included three visits by a research team member. The agenda for each visit was informed by the problem-solving theoretical framework and was customized based on the most pressing problems identified by the caregivers. We enrolled 29 caregivers. Patient's pain was the most frequently identified problem. On average, caregivers reported a higher quality of life and lower level of anxiety postintervention than at baseline. An examination of the caregiver reaction assessment showed an increase of positive esteem average and a decrease of the average value of lack of family support, impact on finances, impact on schedules, and on health. After completing the intervention, caregivers reported lower levels of anxiety, improved problem solving skills, and a reduced negative impact of caregiving. Furthermore, caregivers reported high levels of satisfaction with the intervention, perceiving it as a platform to articulate their challenges and develop a plan to address them. Findings demonstrate the value of problem solving as a psycho-educational intervention in the hospice setting and call for further research in this area.

Introduction

Informal caregivers, namely spouses, family members, friends, or others who assume an unpaid caregiving role for a loved one, are key participants in the delivery of hospice services. Recent research has highlighted the importance of understanding the risks and unmet needs of informal caregivers of patients at the end of life.1 Lay caregiving is crucial to the provision of end-of-life care for patients with terminal illness who choose to die outside of a hospital or acute care setting. Caregivers are at greater risk for depression, deteriorating physical health, financial difficulties, and premature death than demographically similar non-caregivers.2,3 Health and psychological risks are compounded by the fact that caregivers are less likely to engage in preventive health behaviors, or otherwise attend to their own health needs, placing them at risk for deterioration of existing chronic health problems.4 Schultz and Beach5 found that mortality risks were 63% higher in elderly caregivers who were experiencing distress compared to those who were providing care but did not feel stressed. In spite of the identified need to support hospice caregivers, a systematic review6 of scientific literature identified very few interventions specifically targeting caregivers, and only two that were tested within a randomized control trial design. As caregivers deal with complex and stressful challenges, psycho-educational or cognitive–behavioral interventions may be appropriate to assist with coping and problem solving.

Problem solving is defined as “the self-directed cognitive-behavioral process by which a person attempts to identify or discover effective or adaptive solutions for specific problems encountered in everyday living.”7 This cognitive–behavioral process presents a variety of potentially effective solutions for a particular problem and increases the likelihood of selecting the most effective solution from among the various alternatives.7,8 Thus, problem solving is conceived “as a conscious, rational, effortful and purposeful activity.”7 Depending on the problem-solving goals, this process may be aimed at changing the problematic situation for the better, reducing the emotional distress that it produces, or both.

A problem is defined as any life situation or task (present or anticipated) that demands a response for adaptive functioning, but where “no effective response is immediately apparent or available to the person due to the presence of one or more obstacles.”7 The demands in a problematic situation may originate in the environment or context in which one finds themselves (e.g., objective task demands) or within the person (e.g., a personal goal or need). The theoretical framework for this study and also a foundation for the Problem Solving Intervention is the relational/problem-solving model of stress by D'Zurilla and Nezu.7 This model integrates Lazarus'9 relational model of stress. According to Lazarus, a person in a stressful situation significantly influences both the quality and intensity of stress responses through two major processes: (1) cognitive appraisal and (2) coping.10

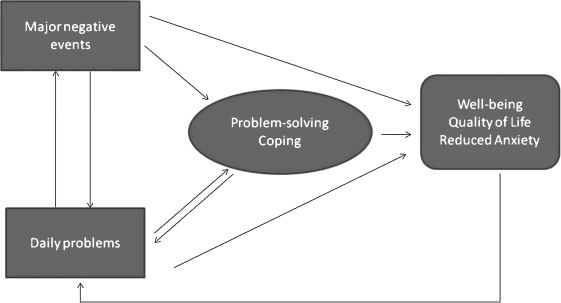

In the expanded relational/problem-solving model, stress is viewed as a function of the reciprocal relations among stressful life events, emotional stress responses, and problem-solving coping. Stressful life events are life experiences that present a person with strong demands for personal, social, or biologic readjustment.11 Two types of stressful life events are major negative events and daily problems. Regardless of what goals are set, the ultimate expected outcome of problem solving is to reduce and minimize the negative effects of stressful life events on well-being and quality of life. Figure 1 demonstrates the relational/problem solving model.

FIG. 1.

The relational/problem-solving model of D'Zurilla and Nezu based on Lazarus' Relational Model.

The Problem Solving Intervention (PSI) focuses on behavioral change principles derived from this theoretical framework. PSI addresses four skills: (1) problem definition and formulation, which involves gathering data and information, articulating the issue in clear terms, identifying the challenge, and setting realistic goals; (2) generation of alternative strategies; (3) decision making; and (4) solution implementation.7 The actual approach to delivering the PSI is summarized by the acronym ADAPT, which includes the following steps:

A = Attitude (suggests that before one attempts to solve a problem, an individual should adopt a positive, optimistic attitude).

D = Define (recommends that individuals define the problem by obtaining relevant facts, identifying obstacles and specifying realistic goals).

A = Alternatives (encourages generation of a variety of alternatives for overcoming the identified obstacles and achieving goals).

P = Predict (asks individuals to predict both the positive and negative consequences of each alternative and choose the one with the highest probability of achieving the goal).

T = Try Out (instructs individuals to implement the solution in real life and monitor its effects).7

PSI is a brief, structured, cognitive–behavioral intervention that teaches people problem-solving coping skills to help them deal with major negative life events as well as daily problems that are making them anxious or depressed.12 Researchers have applied PSI to a wide variety of patient populations and program goals. Specifically, when it comes to family caregivers, PSI has been tested and found effective when delivered to family caregivers of physically or cognitively impaired older adults,13 caregivers of patients with dementia,14 and caregivers of individuals with traumatic brain injury.15 The application of PSI specifically in the hospice setting has not been systematically explored, but the success of PSI in other settings for family caregivers of patients with chronic and in some cases terminal illness, calls for its evaluation in hospice. McMillan et al.16 developed and studied a coping skills nursing intervention labeled COPE that is based on some of the PSI principles and found that this intervention has the potential to improve quality of life for caregivers of hospice cancer patients. The intervention did not follow the entire PSI protocol and did not focus on caregivers' own emotional needs, but rather focused only on practical challenges associated with caregiving tasks relevant to oncology patients' symptoms.

The aim of our study was to explore a problem-solving intervention for hospice caregivers and demonstrate the feasibility of PSI targeting informal caregivers of hospice patients. Furthermore, our pilot study aimed to explore the impact of PSI on caregiver quality of life, problem solving ability and caregiver anxiety, and to assess caregivers' perceptions of PSI and its potential during the caregiving experience.

Methods

For this pilot study, we enrolled hospice caregivers who were receiving outpatient services from our participating hospice agencies. These agencies were in Seattle, and were both Medicare and Medicaid certified. Total home admissions per year were 2619 for Hospice Agency A, and 1325 for Hospice Agency B; average daily census respectively 510 and 189, medial length of stay 27 days and 22 days respectively with average length of stay 65.2 days for Agency A and 59 for Agency B.

Inclusion criteria of caregivers were:

Enrolled as a family/informal caregiver of a hospice patient

18 years or older

Access to a standard phone line at home

Without functional hearing loss or with a hearing aid that allows the participant to conduct telephone conversations as assessed by the research staff (by questioning and observing the caregiver)

No or only mild cognitive impairment

At least a sixth-grade education

Caregivers were approached by a member of the hospice admissions team and asked if they would consent to being contacted by researchers exploring the value of a problem-solving intervention. If caregivers agreed to be contacted, the hospice staff forwarded the caregiver's contact information to a research team member who then contacted the caregiver to schedule a face-to-face meeting to go over the study purpose and details, and to assess eligibility. If caregivers agreed to participate during that visit and signed the informed consent form, they were asked to review and prioritize common caregiver concerns using a checklist that also allows them to define problems not included in the list. The three intervention visits were scheduled between days 5 and 16 of the hospice admission, as close to days 5, 11, and 16 as possible. Each intervention visit lasted approximately 45 minutes. The agenda for the first visit (5–7 days after hospice admission) included an explanation of the purpose of the meeting and confirmation of the three specific problems the caregiver had selected from the concern list. During that visit, the research coordinator worked on steps one and two of the ADAPT model, namely “Attitude” and “Defining the Problem and Setting Realistic Goals.” During the second visit (11–13 days after hospice admission) the interventionist covered steps three and four of the ADAPT model. Step three encourages caregivers in being creative and generating alternative solutions. Step four focuses on predicting the consequences and developing a solution plan. The third visit (16–18 days after hospice admission) focused on step five, namely trying out the solution plan and determining if it works. Intervenionists were trained to account for flexibility in the protocol should a caregiver choose to work on different problems after the initial assessment.

Caregivers received a phone exit interview by a member of the research team a few days after the last study visit. This interview assessed how caregivers perceived the intervention, features they found useful or challenging, and whether such an intervention should become part of standard hospice services. The exit interview was audio-taped by a member of the research team after the caregiver provided verbal consent to do so.

The following measures were used in the pilot study:

Caregiver Quality of Life Index—Revised (CQLI-R): The CQLI-R, a measure of caregivers' quality of life (QOL), includes four dimensions: emotional, social, financial, and physical.17 This four-item instrument was designed specifically for hospice caregivers and its reliability and validity have been established.17 Our research team has revised the CQLI instrument for use in oral interviews using 0 and 10 for each of the four anchors in place of the visual analogue scale.18 Cronbach α for the revised instrument (CQLI-R) was 0.769, and test–retest reliability was supported (rs = 0.912, p < 0.001).

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI): The STAI was initially conceptualized as a research instrument for the study of anxiety in adults. It is a self-report assessment instrument that includes separate measures of state and trait anxiety. The present study specifically investigated state anxiety, defined as a “transitory emotional state or condition of the human organism that is characterized by subjective, consciously perceived feelings of tension and apprehension, and heightened autonomic nervous system activity.”19 Research on this index supports its reliability, with Cronbach α scores of 0.83 to 0.92.20 Validity for this instrument is supported by prior concurrent and construct validity testing.20

Problem Solving Inventory (PSI): The PSI is a 35-item Likert-type inventory that serves as a measure of problem-solving appraisal, or an individual's perceptions of their problem solving behavior and attitudes.21 This instrument is derived from the five stage social problem solving model by D'Zurilla and Goldfried. It includes three subscales: problem-solving confidence, approach–avoidance style, and personal control. The total score is used as an overall index of problem-solving ability. Reliability and validity of this instrument have been documented extensively (Cronbach α reported at 0.85).

The Caregiver Reaction Assessment Scale (CRA): The CRA is a 24-item instrument designed to assess specific aspects of the caregiving situation, including both negative and positive dimensions of caregiving reactions.22 Five dimensions of caregiver reactions include: the impact of caregiving on the caregiver's schedule, impact of caregiving on caregiver's financial situation, degree of family support, impact of caregiving on caregiver's health status, and the degree to which the caregiver views caregiving as rewarding. Cronbach α varied between 0.62 and 0.83 for the separate subscales.

Demographic data: Standard demographic data were collected on caregivers, including age, gender, education level, marital status, occupation, and diagnosis of patient.

Table 1 shows the timeline for the intervention and data collection. Caregiver assessment using the psychometric instruments described earlier, occurred during the first and last interaction (Table 1).

Table 1.

The Problem Solving Intervention and Data Collection Timeline

| 1 (day 1–3) | 2 (day 5) | 3 (day 11) | 4 (day 16) | 5 (day 23) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline measures (CQLI-R, PSI, CRA, STAI, demographic data) | Problem solving Intervention Visit 1 | Problem solving Intervention Visit 2 | Problem solving Intervention Visit 3 (CQLI-R, CRA) | Postintervention measures (STAI, PSI) Exit interview Via phone |

CQLI-R, Caregiver Quality of Life Index—Revised; PSI, Problem Solving Intervention; CRA, Caregiver Reaction Assessment Scale; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.

Subjects received a $50 gift card at the conclusion of their participation in the study as a sign of appreciation for their participation. If the patient died before all scheduled visits took place, subjects received their gift card at that time and their participation in the study was discontinued as they were referred to the appropriate bereavement services provided by their hospice agency.

Results

We enrolled 29 caregivers in this pilot study. Enrollment was based on 33 referrals received from participating agencies; we were able to contact 29 caregivers who did enroll in the study while we were not able to reach four caregivers (after having conducted per our protocol three unreturned phone calls within a week). Twenty-two subjects were female and 7 were male. Thirteen had some college education, 7 had a college degree, 2 had a professional diploma and 7 had completed graduate education. Twenty-five caregivers were white/Caucasian, 1 was African American, 2 were Asian American, and 1 was Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. In terms of relationship to the patient, 14 caregivers were taking care of a spouse/partner, 11 were taking care of a parent, 2 of their sibling, 1 of their adult child, and 1 identified their relationship to the patient as “other.” Twenty-two of the caregivers resided with the patient, whereas the remaining 7 were residing elsewhere. Each caregiver identified the three most pressing problems they were facing (leading to 87 recordings of problems for all 29 caregivers). These 87 recordings included 79 unique problems (as in some cases the same problems were selected by more than one caregivers.) Patient's pain was the most frequently identified problem. Table 2 shows the problems and the frequency of occurrence.

Table 2.

Pressing Problems Identified by the Twenty-Nine Caregivers

| Number of caregivers who identified the problem N (% of all 87 recordings) | |

|---|---|

| Patient's pain | 11 (12.6%) |

| Patient's mental confusion | 8 (9.2%) |

| Needing respite/extra help | 7 (8%) |

| Communication with patient | 6 (6.8%) |

| Patient's fatigue | 6 (6.8%) |

| Financial concerns | 6 (6.8%) |

| Help during final weeks | 5 (5.7%) |

| Depression | 5 (5.7%) |

| Shortness of breath (SOB) | 5 (5.7%) |

| Patient's constipation | 5 (5.7%) |

| Growing anxiety | 3 (3.4%) |

| Dealing with grief | 3 (3.4%) |

| Nutrition | 1 (1.1%) |

| Patient's seizures | 1 (1.1%) |

| Communication with health care providers | 1 (1.1%) |

| What to do postdeath | 1 (1.1%) |

| Focus at being productive at work | 1 (1.1%) |

| Providing support for relative and friends | 1 (1.1%) |

| Concern about the quality of patient care | 1 (1.1%) |

| Caregiver's own stability/frailty and how it may interfere with caregiving | 1 (1.1%) |

| Dealing with other family issues | 1 (1.1%) |

Five participants did not complete all intervention visits because their patient died during their study participation. One participant was lost to follow-up (citing travel obligations). Twenty-three subjects completed the entire intervention. On average, caregivers reported a higher quality of life and lower level of anxiety post-intervention than at baseline. The only subscale within quality of life where the average scores decreased was that of physical dimension of the quality of life. An examination of the CRA shows an increase of positive esteem average and a decrease of the average value of lack of family support, impact on finances, impact on schedules, and on health. Within the CRA, only for the positive esteem subscale does a higher score indicate a positive outcome, whereas for the other subscales a higher score indicates a more severe negative impact of caregiving. Similarly, for the PSI, for all subscales and for the total score, a higher score indicates less effective problem solving. Among participating caregivers, average scores on all PSI subscales and total scores decreased postintervention, indicating an improvement in participants' problem solving skills. Table 3 shows the average scores, standard deviations and p value for all variables pre- and post-intervention and Cohen's d to highlight the standardized difference between means.

Table 3.

Caregiver Variables at Baseline and Postintervention

| |

|

Baseline (n = 29) |

Postintervention (n = 23) |

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average (SD) | Average (SD) | p | Effect size Cohen's d | ||

| CQLI-R | Emotional | 6.96 (2.26) | 6.97 (1.97) | 0.6 | −0.004 |

| Social | 6.56 (3.37) | 6.8 (2.86) | 0.5 | −0.07 | |

| Financial | 6.2 (3.2) | 6.3 (3) | 0.28 | −0.03 | |

| Physical | 6.76 (2.38) | 5.58 (2.19) | 0.32 | −0.004 | |

| Total | 26.48 (8.11) | 27.2 (6.06) | 0.6 | −0.09 | |

| STAI | 41.86 (10.04) | 38.23 (9.94) | 0.12 | 0.36 | |

| CRA | Positive esteem | 28.57 (4.01) | 29.2 (3.9) | 0.1 | −0.15 |

| Lack of family support | 12.04 (5.74) | 10.83 (5.2) | 0.2 | 0.21 | |

| Impact on finances | 6.53 (2.82) | 5.72 (2.1) | 0.17 | 0.28 | |

| Impact on schedule | 19.14 (3.45) | 18.3 (3.4) | 0.4 | 0.25 | |

| Impact on health | 11.33 (3.03) | 9.21 (2.84) | 0.4 | 0.70 | |

| PSI | Problem-solving Confidence | 52.3 (11.09) | 44.2 (10.8) | 0.08 | 0.73 |

| Approach-avoidance Style | 87 (19.62) | 62.1 (16.32) | 0.1 | 1.26 | |

| Personal control | 24 (5.89) | 17.2 (4.98) | 0.1 | 1.15 | |

| Total | 106 (24.06) | 87.6 (23.25) | 0.1 | 0.76 |

SD, standard deviation; CQLI-R, Caregiver Quality of Life Index—Revised; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; CRA, Caregiver Reaction Assessment Scale; PSI, Problem Solving Inventory.

All subjects described the intervention as useful during the exit interviews. One participant stated that the intervention “helped me understand I should not feel guilty about some of my feelings. I never really thought of myself as being a problem solver, this helps me … I didn't know there were services for any of my needs.” Another participant stated “this helps me know I am doing something right as a caregiver … and that the things I don't do right, I can figure them out.” Participants commented on the opportunity that the intervention provides, to focus on specific issues and spend time addressing them and preparing next steps. One participant commented that “this [the intervention] helped me zero in and focus … yes, extremely helpful, talking it through.” Another participant stated: “definitely, it helps to bring focus. It's big issues, lifetime stuff, you know, this is related to the whole picture of life. You coming here was for me a significant nudge, a supportive nudge, it was really heaven-sent.” Another participant described the intervention as “remarkably supportive.”

A specific advantage of the intervention as stated by several participants was that it had structure and provided specific tools. One participant noted: “a lot of time the social workers will come out and they will say, what can I do for you? You're in this position, well, I don't know what you can do for me, I don't know what you have to offer, I don't know what your agency encompasses, I need you to tell me what you can do for me. There are so many decisions, you are so overwhelmed, that all of a sudden somebody asks you a question like that and it is like, I don't know, I don't even know my own name half the time, what do you want? But this [the intervention] had a structured way, it had steps to follow and think about, and think back, and move forward … ”

Further identified advantages included the convenience of its delivery in one's home, the opportunity to take the time and reflect on one's options and strategize/prioritize to prepare for challenging times.

When asked about disadvantages, problems, or challenges associated with the intervention, all but two could not identify any. One participant expressed the concern about discussing problems that pertained to the patient in a residential setting that did not provide privacy for these conversations. Another participant commented on the psychometric instruments and specifically, the CRA that assumed a network of family members or friends, an assumption that did not apply to that participant's case and made it difficult to respond to the instrument's items.

All participants agreed that this intervention should become part of standard hospice services. One participant emphasized: “Yes, I think it would be helpful [to have the intervention be part of standard care]. I think for the mere fact that we get so busy with the caretaking that we don't think about this unless somebody says something. And then we realize how much we need it. ” Another participant pointed out that “[problem solving intervention] should become part of standard hospice [services], especially when you enter hospice and you don't have that much information, having a person supporting you, pushing you forward to make things, solve problems, not just the medical problems, you often have to reach out to them, but you came to me-and that makes a big difference.”

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate the potential of this PSI for hospice caregivers. After completing the intervention, caregivers reported lower levels of anxiety, improved problem-solving skills, and a reduced negative impact of caregiving. Furthermore, caregivers reported high levels of satisfaction with the intervention, perceiving it as a platform to articulate their challenges and develop a plan to address them. As this was a pilot study with a limited sample size, findings do not have statistical significance but given the positive direction of the findings and the comments of the participants who completed the intervention, further and more extensive testing of the PSI in the hospice setting is warranted. It is also worthwhile to investigate whether there is any differential response to the intervention based on race, ethnicity, or culture. In this pilot study, our sample size was very small and did not allow for this investigation. In our small sample we did not see any differences in responses based on race. However, a follow-up study needs to examine this issue given the cultural variations in communication preferences in families coping with a terminal illness.

Based on our experience with this pilot project, we concluded that minor modifications were needed for implementation of the follow-up study. First, we realized that it was important to continue the intervention if it has not been completed while the patient dies, and during bereavement if the caregiver chooses this option. Our original study protocol required subjects to exit the study when their loved one passed away because the intervention was at first conceptualized as a problem solving intervention for active caregivers. However, training to acquire skills and tools to deal with stressful situations continue to be useful, perhaps even more so, during the bereavement phase. While some of the chosen problems pertaining to patients' symptom management would obviously no longer apply, there may be other pressing issues that need to be addressed. Therefore, if subjects wish to continue their participation in the study, it is important for them to have that option. A second modification includes the addition of caregivers' problem solving inventory assessment 6 months after completion of the intervention steps. The rationale is that the problem solving intervention is designed to equip subjects with skills and problem solving attitudes that can be applied in different settings for life's complex problems. Long-term assessment can indicate whether problem solving ability improved and whether such an improvement sustained over time. This pilot study allowed us to test all psychometric instruments proposed for this study and finalize the intervention manual.

The findings of this pilot study demonstrate the feasibility of the problem solving intervention for hospice caregivers and give strength to the argument that it may become an appropriate tool to reduce caregivers' anxiety and enable them to deal with stressful situations. One of the barriers to adoption of not only this but any cognitive behavioral intervention in hospice practice pertains to the increased resources it requires, particularly the increases in visits by clinicians and associated travel costs. Hospice agencies cannot easily extend the frequency or intensity of services they provide because of barriers such as difficulties in recruitment of essential health professionals, insufficient reimbursement, and restrictive regulatory definitions of service areas based on mileage and driving time. Information technology applications can bridge geographic distance. It is often hypothesized that the video-mediated communication introduced by the use of videophones allows for the transmission of nonverbal cues and messages pertaining to one's emotional state and may thus be more appropriate for the delivery of cognitive–behavioral interventions compared to the regular phone. We have initiated a large clinical trial, currently underway, designed as an equivalence trial in which hospice caregivers are randomly assigned to a face-to-face group receiving the problem solving intervention in face to face visits (similar to the pilot study) or to a video group receiving the intervention via a videophone. We will examine the effectiveness of the intervention delivered through these two modalities and the impact on caregiver problem solving ability, anxiety, and quality of life.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Nursing Research Grant Nr. R21 NR010744-01 (A Technology Enhanced Nursing Intervention for Hospice Caregivers, Demiris PI).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Pinquart M. Sorensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health: A meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2003;18:250–267. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dean M. A law that would care for carers. Lancet. 1995;345:1101. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90827-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherwood PR. Given CW. Given B. von Eye A. Caregiver burden and depressive symptoms: Analysis of common outcomes in caregivers of elderly patients. J Aging Health. 2005;17:125–147. doi: 10.1177/0898264304274179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schultz R. Newsom J. Mittelmark M. Burton L. Hirsch C. Jackson S. Health Effects of Caregiving: The Caregiver Health Effects Study. An ancillary study of the Cardiovascular Health Effects Study. Ann Behav Med. 1997;19:110–116. doi: 10.1007/BF02883327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulz R. Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality. The caregiver health effects study. JAMA. 1999;282:2215–2219. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harding R. Higginson IJ. What is the best way to help caregivers in cancer palliative care? A systematic literature review of interventions and their effectiveness. Palliat Med. 2003;17:63–74. doi: 10.1191/0269216303pm667oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D'Zurilla TJ. Nezu AM. Problem Solving Therapy. A Positive Approach to Clinical Intervention. 3rd. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.D'Zurilla TJ. Goldfried MR. Problem solving and behavior modification. J Abnorm Psychol. 1971;78:107–126. doi: 10.1037/h0031360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lazarus RS. Psychological Stress and the Coping Process. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lazarus RS. Stress, Emotion: A New Synthesis. New York: Springer Publishing; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bloom BL. Stressful life event theory, research: Implications for primary prevention. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; DHHS Publication No (AMD) 85–1385. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mynors-Wallis L. Problem Solving Treatment for Anxiety and Depression: A Practical Guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallagher-Thompson D. Lovett S. Rose J. McKibbin C. Coon D. Futterman A. Thompson LE. Impact of psychoeducational interventions on distressed caregivers. J Clin Geropsychol. 2000;6:91–110. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts J. Browne G. Milne C. Spooner L. Gafni A. Drummon-Youn M. LeGris J. Watt S. LeClair K. Beaumont L. Roberts J. Problem solving counseling for caregivers of the cognitively impaired: Effective for whom? Nurs Res. 1999;48:162–172. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199905000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wade SL. Wolfe C. Brown TM. Pestian JP. Putting the pieces together: Preliminary efficacy of a web-based family intervention for children with TBI. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30:437–442. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McMillan SC. Small BJ. Weitzner M. Schonwetter R. Tittle M. Moody L. Haley WE. Impact of coping skills intervention with family caregivers of hospice patients with cancer: A randomized clinical trial. Cancer. 2006;106:214–222. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMillan SC. Mahon M. The impact of hospice services on the quality of life of primary caregivers. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1994;21:1189–1195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Courtney KL. Demiris G. Parker Oliver D. Porock D. Conversion of the CQLI to an interview instrument. Eur J Cancer Care. 2005;14:463–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2005.00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spielberger CD. Gorsuch RL. Lushene RE. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Self Evaluation Questionaire) Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spielberger CD. Gorsuch RL. Lushene R. Vagg PR. Jacobs GA. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults Manual. Redwood City, CA: Mind Garden, Inc.; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heppner PP. Petersen CH. The development and implications of a personal problem solving inventory. J Couns Psychol. 1982;29:66–75. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Given CW. Given B. Stommel M. Collins C. King S. Franklin S. The caregiver reaction assessment (CRA) for caregivers to persons with chronic physical and mental impairments. Res Nurs Health. 1992;15:271–283. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770150406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]