Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to use array-CGH to detect causal microdeletions in samples of subjects with cleft lip and palate.

Subjects

We analyzed DNA samples from a male patient and parents that was seen during surgical screening for an Operation Smile medical mission in the Philippines.

Method

We used Affymetrix Genome Wide Human SNP Array 6.0 followed by sequencing and quantitative PCR using SYBR Green I dye.

Results

We report the second case of 3q29 microdeletion syndrome including cleft lip with or without cleft palate and the first case of this microdeletion syndrome inherited from a phenotypically normal mosaic parent.

Conclusions

Our findings confirm the utility of aCGH to detect causal microdeletions; indicate that parental somatic mosaicism should be considered in healthy parents for genetic counseling of the families and discuss important ethical implications of sharing health impact results from research studies with the participant families.

Keywords: microdeletion, cleft, 3q29, mosaicism, ethical

INTRODUCTION

Identification of microdeletion syndromes began with the recognition that syndromic phenotypes are often associated with mental retardation. One of the first classic chromosomal microdeletion syndromes identified was 4p- (Wolfe-Hirschhorn) syndrome (Hirschhorn et al. 1965) in which cleft lip and/or palate is a common feature (Battaglia et al. 2008). Our ability to detect chromosomal microdeletion syndromes is evolving and is greatly enhanced by the use of more advanced molecular technologies especially the use of microarrays.

The 3q29 syndrome was first described by Willat et al (2005) in 6 patients that presented with mild-to-moderate mental retardation, with only slightly dysmorphic facial features similar in most of these patients: a long and narrow face, short philtrum, and high nasal bridge. Autism, gait ataxia, chest-wall deformity, and long and tapering fingers were noted in at least two of six patients and some additional features including microcephaly, cleft lip and palate (CLP), horseshoe kidney and hypospadias, ligamentous laxity, recurrent middle ear infections, and abnormal pigmentation were also described (Willatt et al. 2005). In addition, nineteen other cases have been reported; all of them presented with ear abnormalities, mental retardation, microcephaly and variable other features (Baynam et al. 2006; Krepischi-Santos et al. 2006; Ballif et al. 2008; Li et al. 2009; Pollazzon et al. 2009; Tyshchenko et al. 2009).

We report a new case of 3q29 microdeletion syndrome involving cleft lip identified with the use of Affymetrix® Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0 that has a 1.5 Mb microdeletion at the 3q29 region inherited from a mosaic and unaffected father. To our knowledge this is the first case of mosaicism involving the 3q29 microdeletion syndrome and the second case to present with cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Table 1 shows a summary of all published cases so far and their phenotypic features including this new case.

Table 1.

clinical features compraison of all published cases of 3q29 microdeletion syndrome

| CLINICAL FEATURE | Willat et al. (2005) | Baynam et al. (2006) | Krepisch-Santos et al., (2006) | Ballif et al. (2008)* | Li et al. (2009) | Pollazzon et al. (2009) | Tyshchenko et al. (2009) | Petrin et al. (2009) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autistic features | Yes (2/6) | Yes | Yes (1/7) | No | ||||

| Behavior problems | Yes | |||||||

| Brain abnormalities | Yes in the right posterior cerebral areas and delay of mylenation or mild post hyptoxic-ischemic gliosis |

|||||||

| Broad face | Yes (1/2) | |||||||

| Broad nasal root | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | |||

| Broad nasal tip | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Cardiac | No | No | No | No | Yes PDA (2/2), pulmonic stenosis (1/2), subvalular aoritic stenosis and 1′ pulm hypertension (1/2) |

Yes PDA and mild tricusid valve dysplasia, incomplete block of right branch |

No | |

| Carp shaped mouth | Yes | |||||||

| Cerebral Sigmoid venous thrombosis | No | Yes | No | No | ||||

| Chest wall deformity | Yes (2/6) | No | No | Yes (1/7) | No | |||

| Chronic otitis media | Yes (1/6) | |||||||

| Cleft Lip with or without Cleft Palate | Yes (1/6) | No | No | No | No (2/2) | No | No | Yes |

| Delayed walking | yes (4/6) | Yes | ||||||

| Development Delay | yes (6/6) | Yes | Yes | Yes (1/2) mild motor delay | Yes | Yes | ||

| Down slanting palpebral fissures | Yes (1/6) | Yes | ||||||

| Ears abnormality | Yes cup shaped ears, thickened helices | |||||||

| Ears low set | Yes (4/7) | |||||||

| Ears: large | yes 6(6) | Yes | Yes (4/7) | |||||

| Ears: small | Yes | |||||||

| Ears: posteriorly rotated | yes 1(6) | Yes (4/7) | Yes (1/2) | Yes | ||||

| Ears: protruding | Yes | |||||||

| Eye abnormalities | Yes cateract and microphthalmia OS |

|||||||

| Facial asymmetry | ||||||||

| Frequent head ache | Yes (1/6) | |||||||

| Frontal bossing | Yes (1/6) | Yes (1/2) | ||||||

| Gait problems | yes (3/6) | Yes due to lower limb contractures | Yes (2/7) | No | ||||

| GE reflux | Yes (1/2) | |||||||

| Growth ht and/or wt <50 centile | yes 1(6) failure to thrive as infant | yes below the 50th centile for wt | Yes below 3rd centile for ht and wt |

Yes (1/2) below the 50th centile for ht and wt |

Yes below the 50th centile for ht and wt |

Yes ht 25th centile and wt 10th centile |

||

| Hands and feet anomaly | Yes (4/6); (2) long tapering fingers; (1) 5th finger brachydactyly; (1) clinodactyly 5th finger and 3rd, 4th and 5th toe |

Yes long fingers | Yes simian palmer crease | No | Yes (1/2) single palmar crease and sandal gap toes |

Yes bifid thumb, pes talus valgus, clinodactyly 2nd toe bilaterally |

No | Yes syndactyly |

| High nasal bridge | Yes (4/6) | No | No | Yes (4/7) | No | |||

| High-arcade palate | No | No | Yes | Yes (2/7) | No | |||

| Horseshoe Kidney | Yes (1/6) | No | No | No | No | |||

| Hypospadias | Yes (1/6) | No | No | Yes (1/7) | ||||

| Inguinal hernia | Yes (1/2) | |||||||

| Joint laxity | Yes (1/6) | |||||||

| Long/Narrow face | no | Yes | Yes | No | ||||

| Long/Smooth Philtrum | Yes (1/2) | |||||||

| Low frountal hairline | Yes (1/6) | Yes | ||||||

| Lower limb deformity | no | Yes flexion contracturs | ||||||

| Macrocephaly | No | No | No | Yes (1/7) | No | |||

| Mental retardation | yes 1(6) IQ= 70 | Yes | Yes | Yes (7/7) | Yes | No | ||

| Microcephaly | Yes (2/6) | Yes | Yes | Yes (5/7) | ||||

| Myopia | Yes | |||||||

| Nasal voice | No | Yes | No | Yes (1/7) | ||||

| Neck-long thin and supple | Yes (1/2) | |||||||

| Oligohydramnios | Yes (1/2) | Yes | ||||||

| Prominent lower lip | Yes (1/6) | |||||||

| Prominent nose | Yes (1/2) | |||||||

| Pyloric stenosis | Yes | |||||||

| Scoliosis | Yes | |||||||

| Short pabebral fissures | Yes (1/2) | |||||||

| Short Philtrum | No | No | No | |||||

| Six Lumbar vertebrae | No | Yes | No | No | ||||

| Skin: increase pigmentation | yes (1/6) | No | No | |||||

| Small nose | Yes | |||||||

| Smooth philtrum | yes 1 (6) | Yes | ||||||

| Special education | Yes (6/6) | yes | ||||||

| Speech delay | Yes (5/6) | Yes | Yes (3/7) | Yes (1/2) | Yes | Yes | ||

| Teeth irregulary spaced | No | Yes | No | Yes (2/7) | ||||

| Thin lips | Yes | |||||||

| Total cases | 6 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

only 7 of 14 patients had clinical information available

Over the past few years, mosaicism of germline and somatic cells has been reported as an important mechanism leading to genetic disease. There have been several clinical descriptions of families in which affected children were born to unaffected parents with no family history of the disease including cases of microdeletion syndromes; in some cases one of the unaffected parents was an asymptomatic mosaic for the microdeletion. The 22q11 region is the most commonly reported microdeletion region showing cases of mosaicism in unaffected parents; 22q deletions are variously known as Velocardiofacial syndrome (OMIM #192430) (Sandrin-Garcia et al. 2002), DiGeorge syndrome (OMIM#188400) (Kasprzak et al. 1998) and 22q11 deletion syndrome (Hatchwell et al. 1998; Saitta et al. 2004; Blennow et al. 2008; Halder et al. 2008). Other examples of microdeletion syndromes include 22q13.3 deletion syndrome (OMIM#606232) (Phelan et al. 2001) and Smith-Magenis syndrome due to a deletion on chromosome region 17p11.2-q12 inherited from a mosaic mother (Zori et al. 1993).

On occasion research produces individual results that bring to light significant health implications it is generally recognized that research results should be offered to patients if they meet one or more of the following criteria: 1) analytical validity, 2) the associated risk for the disease is significant, 3) the disease has important health implications and/or carry significant reproductive risks, and 4) there are therapeutic or prevention interventions available (Bookman et al. 2006). The results for this study have noteworthy implications for the family’s reproductive risks since the father carries an elevated risk to have subsequent children with a 3q29 microdeletion syndrome due to the mosaicism. These results also allow for anticipatory guidance focusing on the range of possible clinical outcomes and associated available treatments that can be offered to the family for this child and subsequent children.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

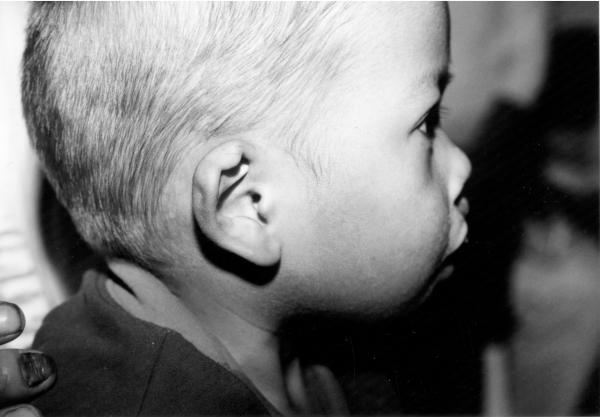

The male patient was the second child of healthy parents and was seen during surgical screening for an Operation Smile medical mission in the Philippines. (Murray et al. 1997). At the time of the patient’s birth the mother was 19 years old and the father was 28 years old. The family history shows a maternal seventh degree relative with an oral cleft, the specific type of cleft is not known. The patient was delivered at home by a midwife. Physical examination at 18 months of age showed broad nasal root, unilateral right sided cleft lip, complete syndactyly of third and fourth toes on the right foot, cup shaped ears with thickened helices as shown on figure 1. Because of the limited time available when screening patients for surgery an evaluation of the child for internal anomalies and cognitive delay was not possible. DNA was obtained using standard techniques from blood on the child and both parents following signed informed consent (IRB # 199804081 and #IRB00003930).

Figure 1.

Phenotypic features of 3q29 microdeletion syndrome case reported by this study: (a) broad nasal root, cleft lip and palate, (b) cup shaped ears, thickened helices, (c) complete syndactyly of third and fourth toes on the right foot

DNA Microarray Analysis

The microdeletion was detected by a genome wide copy number scan that was initially performed on DNA sample from the proband and subsequently from the father using the Affymetrix Genome Wide Human SNP Array 6.0 (Affymetrix, CA, USA). These arrays offers a good genome wide coverage with almost 2 million SNPs and CNV probes and measures DNA copy number differences between a reference genome and the sample genome. The results were analyzed using the Partek Genomics Suite and Affymetrix Genotyping Console software.

SNP sequencing

Following the array analysis we sequenced 43 known SNPs at the apparent boundaries and inside the microdeletion region in DNA from the parents and child looking for evidence of non-Mendelian transmissions from parent to child. We adopted the Conrad et al method of classification of transmission pattern (Conrad et al. 2006). By this method we categorized each transmission event into the following groups: A and B: Mendelian inconsistency compatible with potential deletion of the maternal or paternal alleles respectively, C: Mendelian inconsistency indicating no deletion transmission, D: Consistent with Mendelian inheritance with no information on potential deletions, E and F: Consistent with Mendelian inheritance and compatible with potential deletion of the maternal or paternal alleles respectively, and G: Consistent with Mendelian inheritance and indicating no deletion transmission. Patterns A and B are informative for potential deletion transmission. Patterns A and E are supportive of maternal transmission of a deleted allele, while patterns B and F are supportive of paternal transmission.

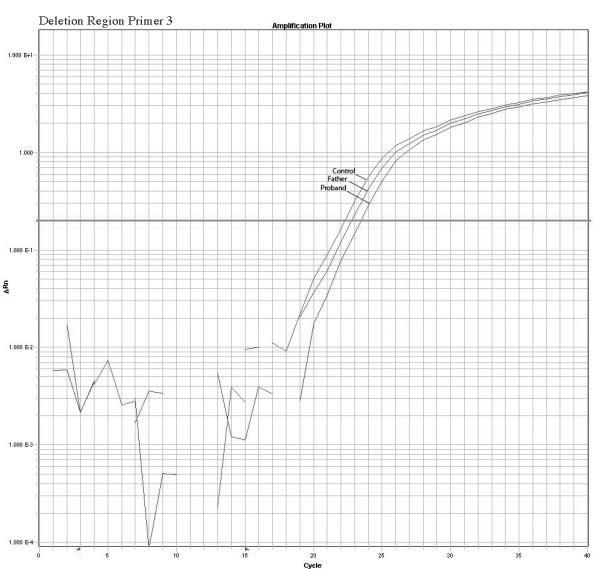

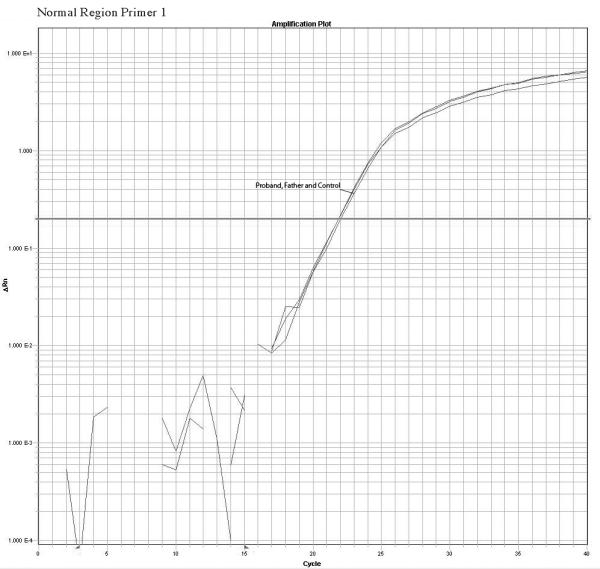

Quantitative Real Time PCR

The quantitative real time PCR was performed with DNA from the proband, father, mother and a normal control using DNA-binding dye SYBR Green I. This method enables both detection and quantification as absolute number of copies of a specific sequence in a DNA sample. We designed 3 different set of primers located inside the deletion region and 1 set of primer in a different chromosome as reference control. All the samples were analyzed in duplicates.

The fold changes per sample were calculated based on methods previously described (Weksberg et al. 2005) . We compared the target samples (proband and father) with normal reference controls to obtain the fold changes.

Where ΔKCt – represents copy number gain or loss per sample (fold changes).

ΔKCt values of 0, (± 0.35) indicating an equal ratio of the test and reference, which corresponds to no loss and therefore no genetic abnormality, or −1 (± 0.35), indicating loss of one copy (microdeletion), for the affected samples. Similarly a ΔKCt values of +1, (± 0.35) would indicate copy gain consistent with microduplication (Weksberg et al. 2005).

RESULTS

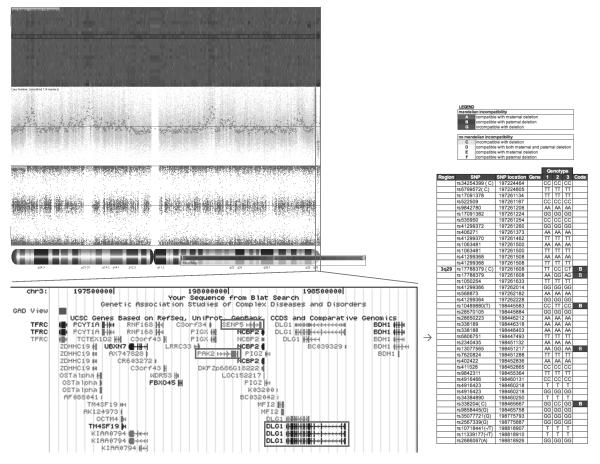

The microarray analysis revealed a 1.5 Mb microdeletion in the proband encompassing 22 genes including DLG1 and PAK2. The deletion is at the same chromosomal location as the previous published cases of 3q29 microdeletion syndrome (Willatt et al. 2005). Following the microarray analysis we sequenced 43 SNPs at the apparent boundaries and inside the microdeletion in DNA from the parents and child looking for evidence of non-Mendelian transmissions from parent to child. Five SNPs showed mendelian inconsistency compatible with deletion on the paternal chromosome (the remaining SNPs were not informative), no heterozygous genotypes were seen in the proband. Figure 2 shows details of the deleted region.

Figure 2.

Details of the deleted region – (A) heat map showing the deletion at the region 3q29 (red rectangle); (B) larger view of the deleted region based on UCSC Genome Browser, important genes are highlighted by red rectangles; (C) sequenced SNPs at boundaries and inside the deleted region showing mendelian inconsistency compatible with deletion on the paternal chromosome

Based on the SNP sequencing results we analyzed the father’s DNA sample with the Affymetrix Genome Wide Human SNP Array 6.0 (Affymetrix, CA, USA) to assess the father’s status for the microdeletion. Surprisingly in the father’s DNA analysis showed the same 1.5Mb microdeletion at the chromosomal region 3q29 and due to his normal phenotype the hypothesis of parental mosaicism for the microdeletion was tested.

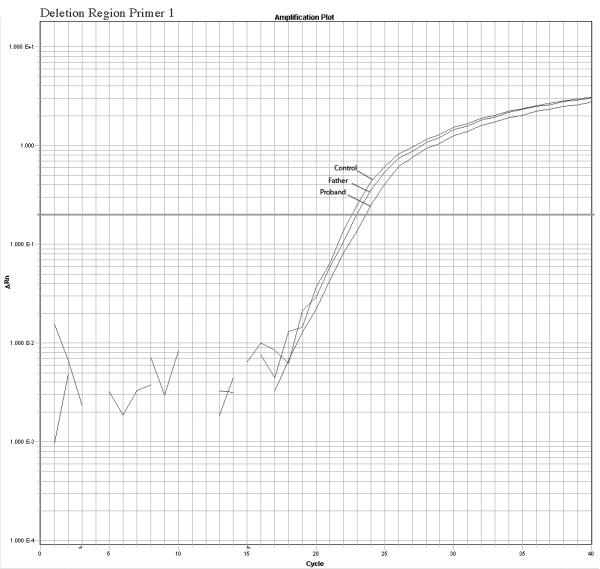

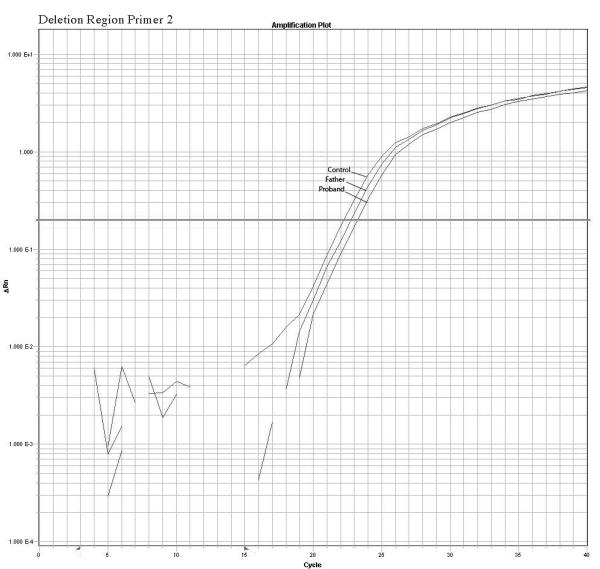

The quantitative Real Time PCR results supported the mosaicism hypothesis showing a different amplification pattern for the proband and father when compared with normal controls. We observed a reduction in relative copy number in these two samples but the father’s reduction was smaller than the proband’s indicating a higher number of copies present in the father sample compared to the proband sample. Fold changes calculations revealed ΔKCt consistent with loss of 1 copy in the proband and loss of 0.4 copies in the father that are consistent with mosaicism of about 40% in the DNA extracted from the father’s white blood cells. No other paternal tissues were available for analysis. The mother’s sample had normal values. A summary of the quantitative PCR method is presented in the figure 3. Table 2 shows the copy number calculation where: Ct represents the point at which the fluorescence crosses the threshold; KCt is the corrected Ct value and ΔKCt represents copy number gain or loss per sample (fold changes). The analysis show ΔKCt values consistent with loss of 1 and 0.44 copies for the proband and father respectively.

Figure 3.

Confirmation of the microarrays results and detection of mosaicism by quantitative PCR using 3 primers inside the deleted region and 1 primer in a normal control region. The plots show a different pattern of amplification for control, Father and proband samples. The control samples amplifies normally while the proband sample present the higher delay of amplification due to the deletion, the father presents a intermediate delay due to the presence of both deleted and normal cells supporting the hypothesis of mosaicism.

Table 2.

Copy Number calculations based on qPCR with SybrGreen

| Primer | Sample | Ct | KCt | ΔKCt | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deletionregion | primer1 | Proband | 23.58 23.42 |

23.50 | −0.91 | loss of 1 copy |

| primer2 | 23.09 23.21 |

23.15 | −0.96 | |||

| primer3 | 23.09 23.43 |

23.26 | −0.96 | |||

| primer1 | Father | 22.94 23.11 |

23.02 | −0.43 | loss of 0.44 copies | |

| primer2 | 22.73 22.37 |

22.55 | −0.36 | |||

| primer3 | 22.75 22.92 |

22.83 | −0.54 | |||

| primer1 | Control | 22.54 22.64 |

22.59 | |||

| primer2 | 22.18 22.20 |

22.19 | ||||

| primer3 | 22.39 22.20 |

22.30 | ||||

| primer1 | Mother | 23.06 22.66 |

22.86 | |||

| primer2 | 22.32 22.32 |

22.32 | ||||

| primer3 | 22.39 22.53 |

22.46 | ||||

| Normalregion | primer1 | Proband | 21.65 22.17 |

21.91 | 0.21 |

normal values for 2

copies |

| primer1 | Father | 21.90 21.88 |

21.89 | 0.23 |

normal values for 2

copies |

|

| primer1 | Control | 22.10 22.14 |

22.12 | |||

| primer1 | Mother | 22.17 22.06 |

22.12 | 0.00 |

normal values for 2

copies |

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Sometimes clinical features associated with a known syndrome may not be typical or specific enough to make a diagnosis based only on the phenotypic presentation. In such cases, advances in molecular technologies can improve the detection of chromosomal abnormalities such as microduplications and/or microdeletions that have an etiologic role. Microdeletion and microduplication genetic syndromes are known to be a significant cause of developmental delay and dysmorphology (Lisi et al. 2008); current predictions, based on array comparative genomic hybridization (a-CGH), estimate that 10–20% of individuals with mental retardation and dysmorphic features have a chromosomal imbalance (Koolen et al. 2006; Rosenberg et al. 2006; Lupski 2007).

The current generation of DNA microarrays such as the Affymetrix array SNP 6.0 offer excellent genome wide coverage with almost 2 million SNPs and CNV probes and measure DNA copy number differences between a reference genome and the sample genome. It is possible to determine breakpoints at ultrahigh resolution in DNA targets helping to localize with good precision the boundaries of any microdeletion that may be causative of anomalies such as the 3q29 microdeletion reported here.

This microdeletion is 1.5 Mb in length and encompasses 22 genes, including PAK2 and DLG1, which are autosomal homologues of two known X-linked mental retardation genes, PAK3 and DLG3; and are in the same region reported previously (Willatt et al. 2005) in six patients with 3q29 syndrome. Previous reports show that mutations that cause loss of function in PAK3 and DLG3 result in moderate to severe mental retardation (Allen et al. 1998; Tarpey et al. 2004) and a recent animal model study with DLG1 gene reported that mutant mice exhibit growth retardation and craniofacial abnormalities (Mahoney et al. 2006)

The 3q29 microdeletion syndrome phenotype is variable making the clinical diagnosis challenging; it can include a long and narrow face, short philtrum, high nasal bridge and cleft lip and palate. We documented dysmorphic features in our patient, but were unable to complete a neuro-cognitive assessment. Given all patients with 3q29 microdeletion reported thus far were found to have some form of developmental delay and/or autism it is likely that our patient is also at risk for similar outcomes. To our knowledge we report the second case presenting with cleft lip and the first case of this microdeletion inherited from a mosaic parent presenting with a normal phenotype.

While the general goal of fundamental genetic research is to produce generalizable knowledge, occasionally the research produces individual results that carry significant health implications. The presence of mosaicism in an unaffected parent has major implications for genetic counseling since the potential recurrence risk of transmission is not commonly predicted in apparently de novo cases; usually mosaic cases are identified when the mutation is transmitted to more than one child born to normal parents. Once present, the parental mosaicism for the genomic abnormality raises the chance to have an affected child.

Sharing findings with participant families is sometimes complicated due to ethical, cultural, and geographical issues. Our study is under the purview of two separate Institutional Review Boards (IRB), one in the Philippines and one in the US, each having oversight of different components of the research project. The IRBs do not coordinate their review activities. In order to release the research results we must interpret and satisfy two separate IRB’s standards and procedures and this may cause significant delays in our ability to report results in a timely manner and may even result in conflicting views on whether such information should be returned to the affected family. In addition, the family has limited access to medical genetic and prenatal centers where genetic counseling and prenatal diagnosis services are available. Communicating results to the family is impaired by language differences and possibly cultural differences the family may have to explain the cause of their child’s CLP (Daack-Hirsch, 2009 accepted for publication). Despite these barriers we believe that in this situation the ethical principles of beneficence, respect of persons, and justice obligate the researchers to make results available to the participant families (Knoppers et al. 2006).

We believe the best way to make the results available for the family of our study is to first obtain the appropriate IRB approvals and to collaborate with geneticists from the Philippines. This strategy promotes a culturally sensitive way to deal with access to care, language, and the limited availability of services. We recommend that investigators engaging in cross cultural human genetics research studies include a healthcare provider as an active member of their research team in order to plan for culturally appropriate strategies to report clinically significant research results. We also recommend that a plan for reporting research results is included in the IRB protocols for each IRB involved and that the consent form reflect options for dealing with the research subject’s right to choose whether or not they wish to receive the results.

Our findings confirm the utility of aCGH to detect causal microdeletions; indicate that parental somatic mosaicism should be considered in healthy parents for a more accurate estimate of the recurrence risk and genetic counseling of the families and discuss important ethical implications of sharing health impact results from research studies with the participant families.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to especially thank the family who participated in this study. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant DE08559 and P50 DE09170. We also thank the Operation Smile International who sponsored the Medical mission to the Philippines where the samples and medical information were collected and Cathy Dragan for assistance in figure design.

Supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants DE08559 and DE09170

References

- Allen KM, Gleeson JG, Bagrodia S, Partington MW, MacMillan JC, Cerione RA, Mulley JC, Walsh CA. PAK3 mutation in nonsyndromic X-linked mental retardation. Nat Genet. 1998;20(1):25–30. doi: 10.1038/1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballif BC, Theisen A, Coppinger J, Gowans GC, Hersh JH, Madan-Khetarpal S, Schmidt KR, Tervo R, Escobar LF, Friedrich CA, McDonald M, Campbell L, Ming JE, Zackai EH, Bejjani BA, Shaffer LG. Expanding the clinical phenotype of the 3q29 microdeletion syndrome and characterization of the reciprocal microduplication. Mol Cytogenet. 2008;1(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1755-8166-1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia A, Filippi T, Carey JC. Update on the clinical features and natural history of Wolf-Hirschhorn (4p-) syndrome: experience with 87 patients and recommendations for routine health supervision. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2008;148C(4):246–51. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baynam G, Goldblatt J, Townshend S. A case of 3q29 microdeletion with novel features and a review of cytogenetically visible terminal 3q deletions. Clin Dysmorphol. 2006;15(3):145–8. doi: 10.1097/01.mcd.0000198934.55071.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blennow E, Lagerstedt K, Malmgren H, Sahlen S, Schoumans J, Anderlid B. Concurrent microdeletion and duplication of 22q11.2. Clin Genet. 2008;74(1):61–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookman EB, Langehorne AA, Eckfeldt JH, Glass KC, Jarvik GP, Klag M, Koski G, Motulsky A, Wilfond B, Manolio TA, Fabsitz RR, Luepker RV. Reporting genetic results in research studies: summary and recommendations of an NHLBI working group. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140(10):1033–40. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad DF, Andrews TD, Carter NP, Hurles ME, Pritchard JK. A high-resolution survey of deletion polymorphism in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2006;38(1):75–81. doi: 10.1038/ng1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder A, Jain M, Kabra M, Gupta N. Mosaic 22q11.2 microdeletion syndrome: diagnosis and clinical manifestations of two cases. Mol Cytogenet. 2008;1(1):18. doi: 10.1186/1755-8166-1-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatchwell E, Long F, Wilde J, Crolla J, Temple K. Molecular confirmation of germ line mosaicism for a submicroscopic deletion of chromosome 22q11. Am J Med Genet. 1998;78(2):103–6. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19980630)78:2<103::aid-ajmg1>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschhorn K, Cooper HL, Firschein IL. Deletion of short arms of chromosome 4-5 in a child with defects of midline fusion. Humangenetik. 1965;1(5):479–82. doi: 10.1007/BF00279124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasprzak L, Der Kaloustian VM, Elliott AM, Shevell M, Lejtenyi C, Eydoux P. Deletion of 22q11 in two brothers with different phenotype. Am J Med Genet. 1998;75(3):288–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoppers BM, Joly Y, Simard J, Durocher F. The emergence of an ethical duty to disclose genetic research results: international perspectives. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14(11):1170–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koolen DA, Vissers LE, Pfundt R, de Leeuw N, Knight SJ, Regan R, Kooy RF, Reyniers E, Romano C, Fichera M, Schinzel A, Baumer A, Anderlid BM, Schoumans J, Knoers NV, van Kessel AG, Sistermans EA, Veltman JA, Brunner HG, de Vries BB. A new chromosome 17q21.31 microdeletion syndrome associated with a common inversion polymorphism. Nat Genet. 2006;38(9):999–1001. doi: 10.1038/ng1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krepischi-Santos AC, Vianna-Morgante AM, Jehee FS, Passos-Bueno MR, Knijnenburg J, Szuhai K, Sloos W, Mazzeu JF, Kok F, Cheroki C, Otto PA, Mingroni-Netto RC, Varela M, Koiffmann C, Kim CA, Bertola DR, Pearson PL, Rosenberg C. Whole-genome array-CGH screening in undiagnosed syndromic patients: old syndromes revisited and new alterations. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2006;115(3-4):254–61. doi: 10.1159/000095922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Lisi EC, Wohler ES, Hamosh A, Batista DA. 3q29 interstitial microdeletion syndrome: An inherited case associated with cardiac defect and normal cognition. Eur J Med Genet. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisi EC, Hamosh A, Doheny KF, Squibb E, Jackson B, Galczynski R, Thomas GH, Batista DA. 3q29 interstitial microduplication: a new syndrome in a three-generation family. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146(5):601–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupski JR. Structural variation in the human genome. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(11):1169–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr067658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney ZX, Sammut B, Xavier RJ, Cunningham J, Go G, Brim KL, Stappenbeck TS, Miner JH, Swat W. Discs-large homolog 1 regulates smooth muscle orientation in the mouse ureter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(52):19872–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609326103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray JC, Daack-Hirsch S, Buetow KH, Munger R, Espina L, Paglinawan N, Villanueva E, Rary J, Magee K, Magee W. Clinical and epidemiologic studies of cleft lip and palate in the Philippines. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1997;34(1):7–10. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_1997_034_0007_caesoc_2.3.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan MC, Rogers RC, Saul RA, Stapleton GA, Sweet K, McDermid H, Shaw SR, Claytor J, Willis J, Kelly DP. 22q13 deletion syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 2001;101(2):91–9. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20010615)101:2<91::aid-ajmg1340>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollazzon M, Grosso S, Papa FT, Katzaki E, Marozza A, Mencarelli MA, Uliana V, Balestri P, Mari F, Renieri A. A 9.3 Mb microdeletion of 3q27.3q29 associated with psychomotor and growth delay, tricuspid valve dysplasia and bifid thumb. Eur J Med Genet. 2009;52(2-3):131–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg C, Knijnenburg J, Bakker E, Vianna-Morgante AM, Sloos W, Otto PA, Kriek M, Hansson K, Krepischi-Santos AC, Fiegler H, Carter NP, Bijlsma EK, van Haeringen A, Szuhai K, Tanke HJ. Array-CGH detection of micro rearrangements in mentally retarded individuals: clinical significance of imbalances present both in affected children and normal parents. J Med Genet. 2006;43(2):180–6. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.032268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitta SC, Harris SE, McDonald-McGinn DM, Emanuel BS, Tonnesen MK, Zackai EH, Seitz SC, Driscoll DA. Independent de novo 22q11.2 deletions in first cousins with DiGeorge/velocardiofacial syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;124A(3):313–7. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandrin-Garcia P, Macedo C, Martelli LR, Ramos ES, Guion-Almeida ML, Richieri-Costa A, Passos GA. Recurrent 22q11.2 deletion in a sibship suggestive of parental germline mosaicism in velocardiofacial syndrome. Clin Genet. 2002;61(5):380–3. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2002.610511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarpey P, Parnau J, Blow M, Woffendin H, Bignell G, Cox C, Cox J, Davies H, Edkins S, Holden S, Korny A, Mallya U, Moon J, O’Meara S, Parker A, Stephens P, Stevens C, Teague J, Donnelly A, Mangelsdorf M, Mulley J, Partington M, Turner G, Stevenson R, Schwartz C, Young I, Easton D, Bobrow M, Futreal PA, Stratton MR, Gecz J, Wooster R, Raymond FL. Mutations in the DLG3 gene cause nonsyndromic X-linked mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75(2):318–24. doi: 10.1086/422703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyshchenko N, Hackmann K, Gerlach EM, Neuhann T, Schrock E, Tinschert S. 1.6Mb deletion in chromosome band 3q29 associated with eye abnormalities. Eur J Med Genet. 2009;52(2-3):128–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weksberg R, Hughes S, Moldovan L, Bassett AS, Chow EW, Squire JA. A method for accurate detection of genomic microdeletions using real-time quantitative PCR. BMC Genomics. 2005;6:180. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willatt L, Cox J, Barber J, Cabanas ED, Collins A, Donnai D, FitzPatrick DR, Maher E, Martin H, Parnau J, Pindar L, Ramsay J, Shaw-Smith C, Sistermans EA, Tettenborn M, Trump D, de Vries BB, Walker K, Raymond FL. 3q29 microdeletion syndrome: clinical and molecular characterization of a new syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77(1):154–60. doi: 10.1086/431653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zori RT, Lupski JR, Heju Z, Greenberg F, Killian JM, Gray BA, Driscoll DJ, Patel PI, Zackowski JL. Clinical, cytogenetic, and molecular evidence for an infant with Smith-Magenis syndrome born from a mother having a mosaic 17p11.2p12 deletion. Am J Med Genet. 1993;47(4):504–11. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320470414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]