Abstract

Background

This study aims to establish the likely origin of EEJ (Eastern European Jews) by genetic distance analysis of autosomal markers and haplogroups on the X and Y chromosomes and mtDNA.

Results

According to the autosomal polymorphisms the investigated Jewish populations do not share a common origin, and EEJ are closer to Italians in particular and to Europeans in general than to the other Jewish populations. The similarity of EEJ to Italians and Europeans is also supported by the X chromosomal haplogroups. In contrast according to the Y-chromosomal haplogroups EEJ are closest to the non-Jewish populations of the Eastern Mediterranean. MtDNA shows a mixed pattern, but overall EEJ are more distant from most populations and hold a marginal rather than a central position. The autosomal genetic distance matrix has a very high correlation (0.789) with geography, whereas the X-chromosomal, Y-chromosomal and mtDNA matrices have a lower correlation (0.540, 0.395 and 0.641 respectively).

Conclusions

The close genetic resemblance to Italians accords with the historical presumption that Ashkenazi Jews started their migrations across Europe in Italy and with historical evidence that conversion to Judaism was common in ancient Rome. The reasons for the discrepancy between the biparental markers and the uniparental markers are discussed.

Reviewers

This article was reviewed by Damian Labuda (nominated by Jerzy Jurka), Kateryna Makova and Qasim Ayub (nominated by Dan Graur).

Background

The genetic affinities of the Jewish populations have been studied since the early days of genetics, yet the origin of these populations is still obscure. Some of the studies, trying to establish the origins of the Jewish populations with autosomal markers, claimed that the Jewish populations have a common origin, but others concluded that the Jews are a very diverse group. This corpus of studies has already been critically reviewed [1].

The origin of Eastern European Jews, (EEJ) by far the largest and most important Ashkenazi population, and their affinities to other Jewish and European populations are still not resolved. Studies that compared them by genetic distance analysis of autosomal markers to European Mediterranean populations revealed that they are closer to Europeans than to other Jewish populations [1-3].

EEJ are the largest and most investigated Jewish community, yet their history as Franco-German Jewry is known to us only since their appearance in the 9th century, and their subsequent migration a few hundred years later to Eastern Europe [4,5]. Where did these Jews come from? It seems that they came to Germany and France from Italy [5-8]. It is also possible that some Jews migrated northward from the Italian colonies on the northern shore of the Black Sea [9]. All these Jews are likely the descendents of proselytes. Conversion to Judaism was common in Rome in the first centuries BC and AD. Judaism gained many followers among all ranks of Roman Society [10-13].

The aim of this study is to establish the likely origin of this major Jewish population by using a larger dataset of autosomal markers, and compare the results to analyses based on the available data for the X and Y chromosomes and for mtDNA.

Methods

Six Jewish populations: EEJ, Moroccan Jews, Iraqi Jews. Iranian Jews, Yemenite Jews and Ethiopian Jews, which have been studied for all the autosomal markers used in this study, are included in the analysis. EEJ are defined on the basis of history as those Jews originating from the areas of the Polish-Lithuanian Kingdom and their descendants in bordering regions, encompassing the territories of Russia, Poland, the Baltic States, Belarus, Moldavia, Moldova (the north-eastern part of Romania) and the Ukraine. The Data on the non-autosomal markers were also available for other Jewish populations: Bulgarian Jews (X, mtDNA), Turkish Jews (X, mtDNA), Tunisian Jews (mtDNA), Libyan Jews (Y, mtDNA) and Djerban Jews (Y).

The seventeen autosomal markers are: AK, ADA, PGM1, PGD, ACP, ESD, GPT, HP, GC, J311 MspI & MetH TaqI (both on chromosome 7 near the CF locus), FV G1691A, FII G20210A, MTHFR C677T, CBS 844ins68, ACE ID and PAH XmnI. All the markers are unique-event-polymorphisms, and apart from two insertions (CBS 844ins68, ACE ID) are all SNPs. The first nine markers are polymorphisms of red cell enzymes and serum proteins, and were typed mostly by protein electrophoresis, but the variation at the protein level is directly related in a 1:1 manner to the SNP variation at the DNA level. Indeed, some of the results for the Jewish populations were obtained by PCR methods [1,14]. The polymorphism of the remaining eight markers can only be detected at the DNA level. J311 MspI and MetH TaqI were typed in all the populations including the Israeli populations (unpublished results) by Southern blotting and hybridization [15,16]. The other 6 markers were typed in the Israeli populations by PCR methods. The data on FV G1691A, FII G20210A, MTHFR C677T and CBS 844ins68 have already been published [3,17]. The data on ACE ID and PAH XmnI are still unpublished. These polymorphisms were typed according to the methods of Rigat et al. [18] and Goltsov et al. [19] respectively. Allele frequencies for all the populations are given in Additional file 1: tables S1-4. Table S2 (Additional file 1) presents four markers on both sides of the CF locus. Because of the linkage between them, I chose to use only the two most distal markers, which are separated by a few centimorgans. Haplogroup frequencies of the non-recombining Y chromosome (NRY), the X chromosome (dystrophin locus, dys44, on Xp21.3) and mtDNA are given in Additional file 1: tables S5, S6 and S7 respectively.

Gower (cited in [20]) recommends, that for microevolutionary studies, when sample sizes are quite variable and gene frequencies do not differ greatly, Sanghvi's G2 [21] would be the most appropriate, and this is the measure I used. Distances were also calculated with Nei's [22] formula and the results were very similar (r = 0.990, genetic distance matrix not shown). The neighbor joining tree was computed by PHYLIP 3.66. Since it does not calculate Sanghvi's G2, I used Reynolds et al. distance [23], which is also based on the assumption that gene frequencies change by genetic drift alone, solely for the calculation of the tree (genetic distance matrix not shown). The significance of nodes in the tree and the standard errors of the genetic distances were computed by bootstrapping 10,000 times. Multidimensional scaling plots and Mantel tests for correlation between genetic distance matrices and between them and matrices of geographic distances were computed by NTSYS 1.70. Geographic distances were calculated as great circle distances between the capitals of the countries of origin of the populations (Warsaw was chosen for EEJ). Mantel test significance was assessed by 10,000 permutations.

Results

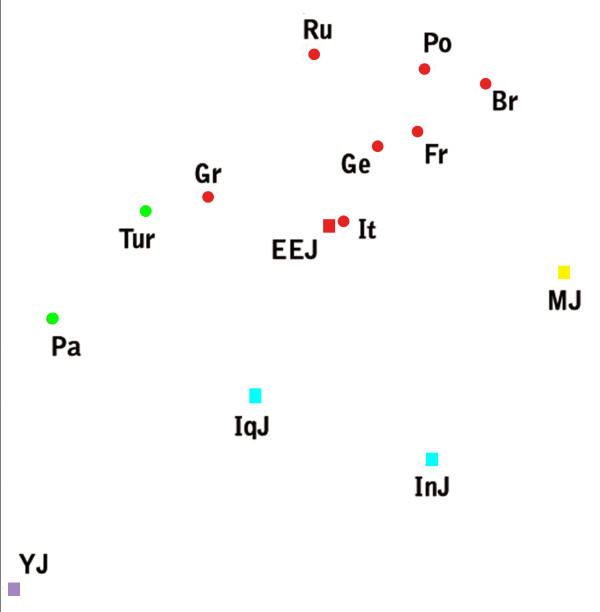

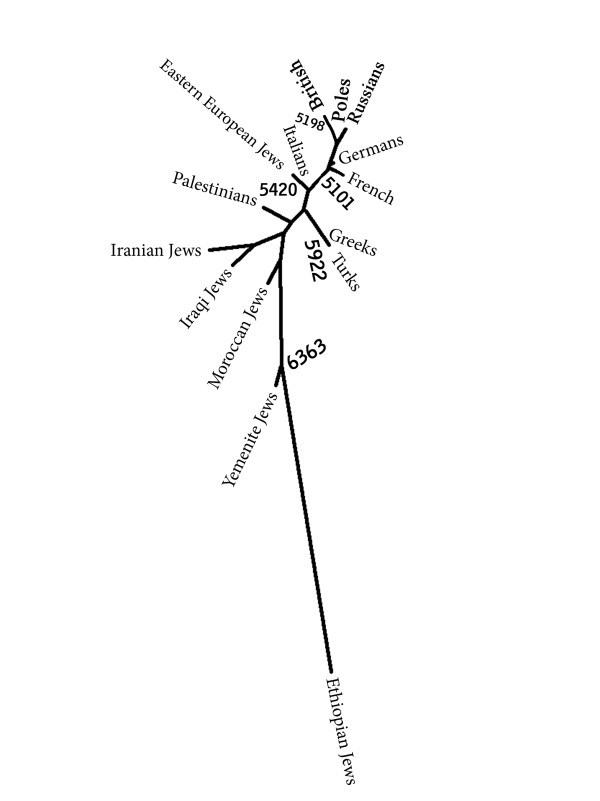

The autosomal genetic distances (table 1) do not show any particular resemblance between the Jewish populations. EEJ are closer to Italians in particular and to Europeans in general than to the other Jewish populations. All of the distances, apart from one, differ from zero by more than twice their standard error. A difference between two distances can be considered meaningful, if it is more than twice their largest standard error. The differences between the distance of EEJ from Italians and their distances from the other Jewish populations are meaningful according to this criterion, and the same is also true for all the Non-Jewish populations except for Greeks and Russians. In fact the distance between EEJ and Italians is the smallest distance in the matrix. A multidimensional scaling plot of the genetic distance matrix (figure 1) captures the proximity of EEJ to Italians and other European populations. The same is also true for the neighbor joining tree (figure 2). It should be noted that multidimensional scaling plots are a way to present graphically the intricate relationships of genetic distance matrices. As such they are necessarily less accurate than the matrices on which they are based. In order to understand the genetic affinities of a particular population, one must examine its distances in the matrix itself, not in the plot. The same also applies to the neighbor joining tree. The bootstrap values indicate the robustness of the clustering, but not the significance of individual genetic distances.

Table 1.

Autosomal genetic distance matrix (×1000) (standard errors above the diagonal)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) EEJ | 103 | 94 | 52 | 180 | 348 | 76 | 57 | 38 | 11 | 35 | 73 | 42 | 94 | 58 | |

| 2) Iraqi Jews | 277 | 68 | 131 | 87 | 330 | 58 | 147 | 117 | 87 | 64 | 125 | 138 | 141 | 99 | |

| 3) Iranian Jews | 275 | 218 | 131 | 118 | 391 | 125 | 112 | 97 | 105 | 119 | 149 | 142 | 146 | 139 | |

| 4) Moroccan Jews | 243 | 330 | 325 | 148 | 263 | 105 | 115 | 89 | 36 | 66 | 71 | 55 | 80 | 78 | |

| 5) Yemenite Jews | 498 | 366 | 335 | 447 | 263 | 87 | 104 | 92 | 162 | 133 | 123 | 114 | 155 | 168 | |

| 6) Ethiopian Jews | 1240 | 1127 | 1004 | 809 | 696 | 233 | 322 | 333 | 349 | 396 | 373 | 341 | 381 | 463 | |

| 7) Palestinians | 277 | 223 | 425 | 298 | 323 | 972 | 43 | 44 | 60 | 65 | 131 | 63 | 87 | 122 | |

| 8) Turks | 170 | 243 | 305 | 314 | 400 | 1244 | 182 | 15 | 54 | 56 | 113 | 117 | 64 | 68 | |

| 9) Greeks | 105 | 270 | 316 | 311 | 356 | 1246 | 202 | 56 | 36 | 38 | 83 | 76 | 42 | 52 | |

| 10) Italians | 44 | 243 | 255 | 167 | 452 | 1083 | 231 | 157 | 101 | 25 | 48 | 34 | 81 | 40 | |

| 11) Germans | 131 | 268 | 294 | 237 | 511 | 1067 | 299 | 179 | 148 | 71 | 25 | 19 | 34 | 12 | |

| 12) British | 238 | 395 | 373 | 239 | 592 | 977 | 434 | 332 | 267 | 151 | 53 | 41 | 46 | 13 | |

| 13) French | 144 | 339 | 398 | 216 | 545 | 974 | 288 | 265 | 192 | 91 | 48 | 75 | 59 | 33 | |

| 14) Russians | 230 | 420 | 430 | 289 | 513 | 1144 | 375 | 175 | 139 | 193 | 102 | 112 | 134 | 25 | |

| 15) Poles | 195 | 405 | 365 | 264 | 600 | 1204 | 465 | 255 | 197 | 139 | 50 | 46 | 102 | 66 | |

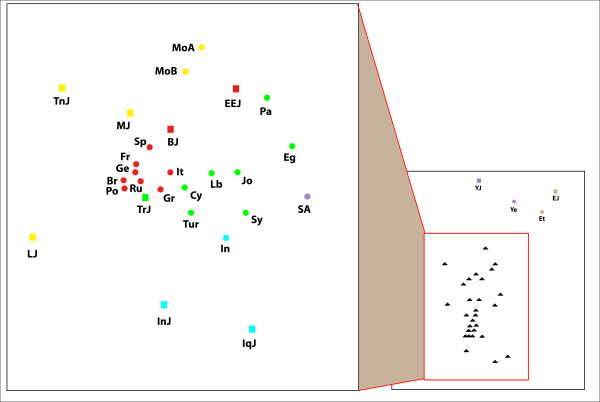

Figure 1.

A multidimensional scaling plot of the autosomal genetic distance matrix excluding Ethiopian Jews. Stress = 0.100. Populations names are: EEJ - Eastern European Jews, IqJ - Iraqi Jews, InJ - Iranian Jews, MJ - Moroccan Jews, YJ - Yemenite Jews, Pa - Palestinians, Tur - Turks, Gr - Greeks, It - Italians, Ge - Germans, Br - British, Fr - French, Ru - Russians, Po - Poles. Squares represent Jews and circles non-Jews. Colour indicates geographic region: red - Europe, green - Eastern Mediterranean, blue - Iran-Iraq, purpule - Arabian peninsula, yellow - North-Africa.

Figure 2.

A neighbor joining tree based on the autosomal polymorphisms. A number next to a node indicates the majority bootstrap support for that node out of 10,000 repetitions.

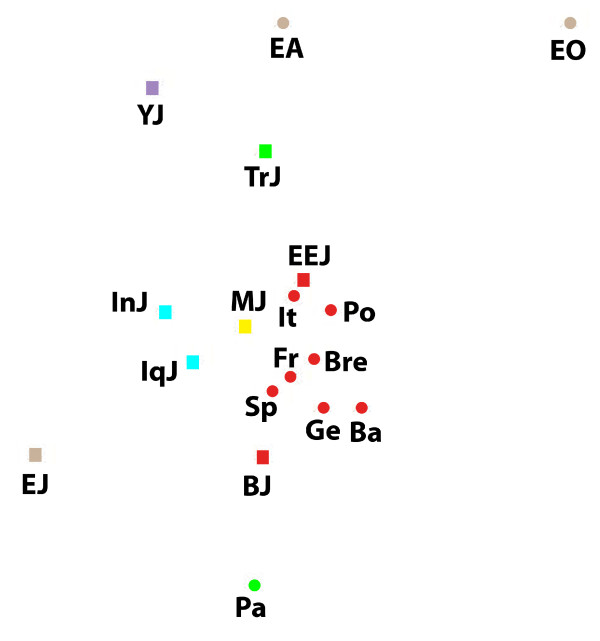

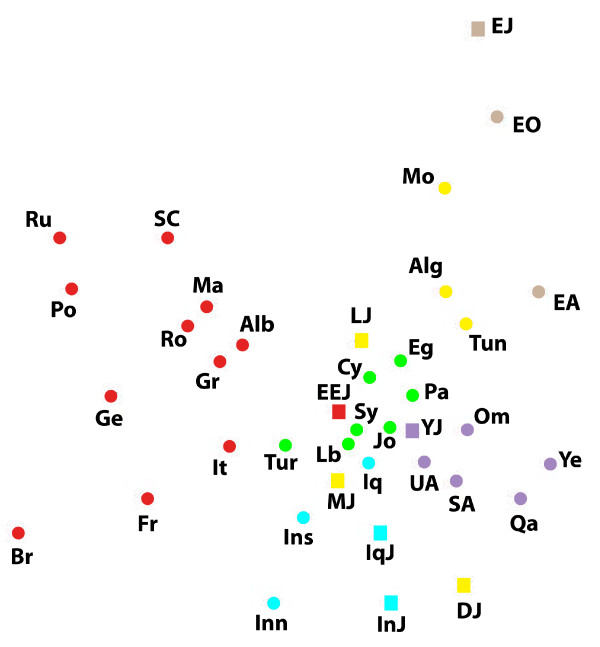

X-chromosomal haplogroups demonstrate the same relatedness of EEJ to Italians and other Europeans (table 2, figure 3). In contrast, according to the Y-chromosomal haplogroups EEJ are closest to the non-Jewish populations of the Eastern Mediterranean (table 3, figure 4). MtDNA shows a mixed pattern where EEJ are about equally close to Moroccan Jews, Palestinians, Italians and Bulgarian Jews, but overall are more distant from most populations and hold a marginal position in the MDS plot, rather than a central one like in the other plots (table 4, figure 5).

Table 2.

X chromosomal genetic distance matrix (×1000)

| 1) EE Jews | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2) Iraqi Jews | 402 | ||||||||||||||||

| 3) Iranian Jews | 497 | 351 | |||||||||||||||

| 4) Moroccan Jews | 302 | 211 | 480 | ||||||||||||||

| 5) Yemenite Jews | 555 | 406 | 512 | 439 | |||||||||||||

| 6) Ethiopian Jews | 533 | 617 | 683 | 676 | 709 | ||||||||||||

| 7) Bulgarian Jews | 409 | 276 | 440 | 299 | 611 | 672 | |||||||||||

| 8) Turkish Jews | 288 | 519 | 474 | 452 | 403 | 599 | 625 | ||||||||||

| 9) Palestinians | 573 | 506 | 512 | 464 | 666 | 754 | 350 | 712 | |||||||||

| 10) Italians | 223 | 374 | 488 | 184 | 493 | 741 | 337 | 395 | 478 | ||||||||

| 11) Germans | 263 | 483 | 497 | 358 | 715 | 701 | 318 | 518 | 502 | 282 | |||||||

| 12) Poles | 233 | 482 | 531 | 336 | 570 | 741 | 406 | 476 | 484 | 235 | 266 | ||||||

| 13) Basques | 311 | 597 | 548 | 513 | 827 | 702 | 378 | 479 | 503 | 369 | 349 | 359 | |||||

| 14) Spaniards | 252 | 385 | 457 | 313 | 609 | 554 | 297 | 406 | 487 | 334 | 315 | 365 | 337 | ||||

| 15) French | 313 | 332 | 454 | 284 | 649 | 706 | 206 | 401 | 483 | 285 | 308 | 347 | 249 | 244 | |||

| 16) Bretons | 186 | 410 | 483 | 386 | 615 | 611 | 288 | 376 | 492 | 288 | 238 | 246 | 234 | 219 | 162 | ||

| 17) Ethiopians Oromo | 771 | 918 | 892 | 906 | 977 | 1243 | 847 | 745 | 1002 | 753 | 816 | 797 | 840 | 840 | 717 | 727 | |

| 18) Ethiopians Amhara | 490 | 618 | 619 | 504 | 471 | 798 | 695 | 433 | 702 | 449 | 614 | 490 | 680 | 579 | 555 | 524 | 791 |

Figure 3.

A multidimensional scaling plot of the X-chromosomal genetic distance matrix. Stress = 0.125. Populations names are: EEJ - Eastern European Jews, IqJ - Iraqi Jews, InJ - Iranian Jews, MJ - Moroccan Jews, YJ - Yemenite Jews, EJ - Ethiopian Jews, BJ - Bulgarian Jews, TrJ - Turkish Jews, Pa - Palestinians, It - Italians, Ge - Germans, Po - Poles, Fr - French, Bre - Bretons, Sp - Spaniards, Ba - Basques, EO - Ethiopians Oromo, EA - Ethiopians Amhara. Squares represent Jews and circles non-Jews. Colour indicates geographic region: red - Europe, green - Eastern Mediterranean, blue - Iran-Iraq, purpule - Arabian peninsula, yellow - North-Africa, brown - Ethiopia.

Table 3.

Y chromosomal genetic distance matrix (×1000)*

| 1) EEJ | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2) IqJ | 341 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3) InJ | 574 | 236 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4) MJ | 245 | 335 | 764 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5) LJ | 242 | 626 | 863 | 465 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6) DJ | 582 | 813 | 1025 | 667 | 402 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7) YJ | 185 | 244 | 472 | 304 | 418 | 545 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8) EJ | 1296 | 1373 | 1444 | 1386 | 1308 | 1685 | 1278 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9) Pa | 192 | 469 | 728 | 362 | 351 | 411 | 215 | 1254 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10) It | 357 | 720 | 1022 | 332 | 538 | 928 | 669 | 1427 | 611 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11) Ge | 815 | 1209 | 1356 | 933 | 1194 | 1614 | 1179 | 1644 | 1196 | 424 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12) Br | 1233 | 1504 | 1801 | 1060 | 1494 | 1727 | 1475 | 1860 | 1474 | 499 | 398 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13) Fr | 754 | 1053 | 1177 | 749 | 1034 | 1299 | 971 | 1622 | 1043 | 307 | 399 | 346 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14) Ru | 1150 | 1303 | 1299 | 1384 | 1504 | 1811 | 1498 | 1737 | 1406 | 1159 | 595 | 1364 | 1255 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15) Po | 1030 | 1388 | 1430 | 1316 | 1359 | 1740 | 1388 | 1687 | 1337 | 971 | 388 | 1119 | 1058 | 185 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16) SC | 834 | 1212 | 1179 | 1216 | 1058 | 1516 | 1161 | 1466 | 1021 | 890 | 511 | 1166 | 910 | 676 | 615 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17) Alb | 349 | 838 | 844 | 677 | 514 | 1099 | 730 | 1316 | 622 | 366 | 441 | 993 | 613 | 749 | 618 | 341 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18) Gr | 380 | 904 | 1064 | 658 | 512 | 1104 | 782 | 1312 | 686 | 255 | 311 | 819 | 498 | 774 | 563 | 531 | 136 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 19) Ma | 517 | 965 | 1135 | 792 | 713 | 1337 | 887 | 1323 | 783 | 440 | 266 | 841 | 592 | 667 | 500 | 222 | 144 | 138 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 20) Ro | 570 | 1029 | 1221 | 833 | 745 | 1193 | 942 | 1476 | 819 | 502 | 409 | 828 | 620 | 889 | 715 | 198 | 274 | 341 | 180 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 21) Tur | 159 | 447 | 700 | 265 | 413 | 696 | 460 | 1421 | 438 | 217 | 599 | 1008 | 622 | 899 | 891 | 845 | 352 | 303 | 490 | 535 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 22) Irn | 494 | 424 | 717 | 369 | 727 | 805 | 601 | 1756 | 820 | 478 | 916 | 1134 | 813 | 1233 | 1285 | 1376 | 869 | 766 | 994 | 990 | 270 | |||||||||||||||||

| 23) Irs | 311 | 509 | 621 | 418 | 516 | 675 | 538 | 1528 | 587 | 566 | 860 | 1410 | 1042 | 874 | 896 | 991 | 529 | 592 | 781 | 773 | 217 | 370 | ||||||||||||||||

| 24) Iq | 245 | 516 | 628 | 374 | 406 | 444 | 320 | 1422 | 265 | 510 | 970 | 1397 | 915 | 1127 | 1113 | 1051 | 557 | 550 | 754 | 859 | 270 | 541 | 315 | |||||||||||||||

| 25) Cy | 127 | 448 | 791 | 196 | 176 | 534 | 246 | 1241 | 240 | 395 | 1064 | 1239 | 799 | 1539 | 1359 | 1099 | 531 | 531 | 714 | 699 | 326 | 595 | 486 | 378 | ||||||||||||||

| 26) Sy | 152 | 464 | 637 | 398 | 322 | 421 | 336 | 1304 | 177 | 508 | 947 | 1429 | 941 | 1043 | 1045 | 911 | 481 | 487 | 655 | 712 | 197 | 562 | 277 | 114 | 329 | |||||||||||||

| 27) Lb | 71 | 256 | 480 | 281 | 334 | 493 | 173 | 1330 | 191 | 426 | 925 | 1288 | 739 | 1213 | 1146 | 956 | 492 | 494 | 651 | 694 | 180 | 416 | 354 | 215 | 211 | 116 | ||||||||||||

| 28) Jo | 183 | 513 | 704 | 373 | 451 | 489 | 141 | 139 | 123 | 561 | 1026 | 1296 | 840 | 1365 | 1247 | 988 | 577 | 661 | 758 | 758 | 410 | 765 | 578 | 246 | 266 | 255 | 204 | |||||||||||

| 29) SA | 448 | 580 | 605 | 606 | 724 | 565 | 372 | 1302 | 339 | 924 | 1286 | 1728 | 1256 | 1302 | 1357 | 1208 | 889 | 962 | 1115 | 1103 | 553 | 757 | 420 | 254 | 610 | 262 | 380 | 334 | ||||||||||

| 30) Qa | 647 | 819 | 805 | 973 | 948 | 696 | 454 | 1483 | 518 | 1196 | 1405 | 1769 | 1360 | 1506 | 1450 | 1351 | 1132 | 1216 | 1327 | 1225 | 903 | 1081 | 690 | 499 | 800 | 546 | 623 | 392 | 153 | |||||||||

| 31) UA | 324 | 457 | 419 | 513 | 676 | 712 | 266 | 1304 | 367 | 818 | 1106 | 1575 | 1125 | 1233 | 1206 | 1050 | 671 | 825 | 956 | 954 | 488 | 694 | 365 | 290 | 500 | 305 | 315 | 295 | 130 | 249 | ||||||||

| 32) Om | 477 | 626 | 625 | 651 | 745 | 765 | 417 | 1144 | 366 | 955 | 1223 | 1754 | 1313 | 1146 | 1227 | 1097 | 804 | 880 | 1001 | 1086 | 586 | 900 | 524 | 289 | 653 | 303 | 474 | 381 | 99 | 279 | 157 | |||||||

| 33) Ye | 769 | 913 | 1000 | 854 | 920 | 586 | 483 | 1438 | 383 | 1240 | 1664 | 1825 | 1407 | 1816 | 1734 | 1502 | 1252 | 1310 | 1412 | 1367 | 1088 | 1341 | 1066 | 542 | 768 | 645 | 710 | 369 | 365 | 238 | 475 | 410 | ||||||

| 34) Eg | 185 | 365 | 655 | 289 | 355 | 742 | 205 | 988 | 183 | 598 | 1128 | 1481 | 1068 | 1305 | 1285 | 1036 | 593 | 647 | 728 | 839 | 384 | 724 | 502 | 350 | 197 | 260 | 242 | 283 | 430 | 677 | 364 | 358 | 672 | |||||

| 35) Mo | 764 | 999 | 1220 | 944 | 611 | 1264 | 801 | 933 | 715 | 1067 | 1543 | 1715 | 1365 | 1775 | 1652 | 1258 | 888 | 938 | 991 | 1125 | 1092 | 1492 | 1251 | 1098 | 559 | 970 | 911 | 903 | 1157 | 1282 | 1055 | 996 | 1105 | 454 | ||||

| 36) Alg | 437 | 641 | 1001 | 456 | 502 | 958 | 425 | 1101 | 350 | 812 | 1325 | 1458 | 1240 | 1632 | 1487 | 1208 | 801 | 874 | 907 | 999 | 793 | 1120 | 909 | 697 | 289 | 654 | 578 | 487 | 783 | 895 | 643 | 676 | 735 | 215 | 272 | |||

| 37) Tun | 456 | 676 | 952 | 522 | 580 | 911 | 345 | 1153 | 316 | 893 | 1335 | 1485 | 1179 | 1653 | 1501 | 1250 | 853 | 919 | 968 | 1078 | 854 | 1193 | 969 | 604 | 332 | 626 | 554 | 356 | 643 | 664 | 528 | 551 | 497 | 251 | 379 | 71 | ||

| 38) EO | 1089 | 1203 | 1319 | 1207 | 1056 | 1659 | 1090 | 452 | 1021 | 1332 | 1648 | 1851 | 1582 | 1701 | 1686 | 1387 | 1134 | 1186 | 1191 | 1418 | 1330 | 1726 | 1442 | 1319 | 967 | 1187 | 1186 | 1231 | 1197 | 1394 | 1190 | 998 | 1319 | 651 | 323 | 569 | 666 | |

| 39) EA | 826 | 932 | 1018 | 907 | 969 | 1107 | 622 | 555 | 569 | 1274 | 1653 | 1857 | 1497 | 1715 | 1692 | 1425 | 1170 | 1261 | 1290 | 1430 | 1154 | 1516 | 1172 | 819 | 790 | 803 | 844 | 676 | 617 | 693 | 677 | 500 | 581 | 449 | 638 | 473 | 397 | 346 |

*- For populations names see figure 4.

Figure 4.

A multidimensional scaling plot of the Y-chromosomal genetic distance matrix. Stress = 0.133. Populations names are: EEJ - Eastern European Jews, IqJ - Iraqi Jews, InJ - Iranian Jews, MJ - Moroccan Jews, LJ - Libyan Jews, DJ - Djerban Jews, YJ - Yemenite Jews, EJ - Ethiopian Jews, Pa - Palestinians, It - Italians, Fr - French, Br - British, Ge - Germans, Ru - Russians, Po - Poles, SC - Serbo-Croats, Alb - Albanians, Gr - Greeks, Ma - Macedonians, Ro - Romanians, Tur - Turks, Inn - Iranians-North, Ins - Iranians-South, Iq - Iraqis, Cy - Cypriots, Sy - Syrians, Lb - Lebanese, Jo - Jordanians, SA - Saudi-Arabians, Qa - Qataris, UA - United Arab Emirates, Om - Omanis, Ye - Yemenites, Eg - Egyptians, Mo - Moroccans, Alg - Algerians, Tun - Tunisians, EO - Ethiopians Oromo, EA - Ethiopians Amhara. Squares represent Jews and circles non-Jews. Colour indicates geographic region: red - Europe, green - Eastern Mediterranean, blue - Iran-Iraq, purpule - Arabian peninsula, yellow - North-Africa, brown - Ethiopia.

Table 4.

mtDNA genetic distance matrix (×1000)*

| 1) EEJ | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2) IqJ | 916 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3) IqJ | 892 | 627 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4) MJ | 400 | 1020 | 814 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5) LJ | 1016 | 1303 | 770 | 741 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6) TnJ | 908 | 1336 | 973 | 438 | 487 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7) BJ | 453 | 817 | 676 | 381 | 727 | 605 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8) TrJ | 591 | 813 | 445 | 287 | 605 | 530 | 300 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9) YJ | 1020 | 1058 | 1257 | 1124 | 1349 | 1323 | 1287 | 1264 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10) EJ | 1685 | 1789 | 1794 | 1882 | 1701 | 1662 | 1844 | 1916 | 1251 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 11) Pa | 417 | 976 | 941 | 674 | 1005 | 812 | 501 | 690 | 843 | 1382 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 12) Tur | 531 | 478 | 419 | 499 | 767 | 795 | 406 | 379 | 985 | 1726 | 556 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 13) Gr | 540 | 676 | 443 | 302 | 680 | 465 | 365 | 228 | 1138 | 1771 | 627 | 199 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 14) It | 437 | 698 | 516 | 324 | 705 | 574 | 295 | 226 | 1247 | 1759 | 582 | 237 | 135 | |||||||||||||||||

| 15) Ge | 606 | 745 | 533 | 360 | 791 | 528 | 360 | 275 | 1299 | 1867 | 701 | 357 | 112 | 176 | ||||||||||||||||

| 16) Fr | 504 | 836 | 646 | 334 | 814 | 590 | 379 | 316 | 1374 | 1880 | 710 | 379 | 173 | 126 | 93 | |||||||||||||||

| 17) Br | 610 | 761 | 562 | 341 | 822 | 602 | 454 | 295 | 1310 | 1927 | 806 | 410 | 166 | 220 | 70 | 84 | ||||||||||||||

| 18) Ru | 650 | 785 | 510 | 411 | 716 | 534 | 432 | 300 | 1355 | 1854 | 697 | 303 | 124 | 148 | 105 | 96 | 142 | |||||||||||||

| 19) Po | 687 | 749 | 585 | 453 | 810 | 561 | 428 | 308 | 1414 | 1886 | 752 | 355 | 156 | 167 | 77 | 100 | 126 | 66 | ||||||||||||

| 20) Sp | 557 | 778 | 680 | 370 | 843 | 657 | 445 | 339 | 1294 | 1719 | 712 | 368 | 251 | 181 | 214 | 167 | 207 | 184 | 206 | |||||||||||

| 21) Cy | 520 | 732 | 539 | 374 | 626 | 600 | 302 | 335 | 1141 | 1689 | 616 | 269 | 244 | 199 | 374 | 363 | 425 | 370 | 407 | 364 | ||||||||||

| 22) Lb | 543 | 736 | 618 | 502 | 729 | 633 | 390 | 456 | 1095 | 1520 | 383 | 233 | 348 | 288 | 485 | 463 | 554 | 425 | 482 | 412 | 270 | |||||||||

| 23) Sy | 581 | 431 | 564 | 676 | 891 | 950 | 580 | 576 | 820 | 1465 | 463 | 283 | 427 | 444 | 613 | 659 | 659 | 609 | 659 | 609 | 412 | 339 | ||||||||

| 24) In | 583 | 553 | 464 | 681 | 879 | 995 | 561 | 571 | 888 | 1697 | 576 | 209 | 422 | 369 | 568 | 579 | 613 | 513 | 576 | 543 | 397 | 425 | 341 | |||||||

| 25) Jo | 591 | 647 | 461 | 672 | 816 | 788 | 562 | 490 | 892 | 1329 | 419 | 387 | 449 | 370 | 613 | 616 | 711 | 563 | 614 | 532 | 355 | 328 | 285 | 405 | ||||||

| 26) SA | 631 | 731 | 799 | 863 | 964 | 1018 | 745 | 801 | 745 | 1123 | 478 | 579 | 679 | 668 | 836 | 875 | 841 | 849 | 898 | 805 | 567 | 561 | 416 | 503 | 486 | |||||

| 27) Ye | 1064 | 1393 | 1351 | 1217 | 1310 | 1427 | 1206 | 1289 | 897 | 830 | 871 | 1078 | 1205 | 1154 | 1343 | 1315 | 1383 | 1314 | 1383 | 1254 | 1110 | 1125 | 949 | 943 | 898 | 770 | ||||

| 28) Eg | 634 | 721 | 853 | 751 | 967 | 895 | 692 | 763 | 791 | 985 | 374 | 556 | 656 | 620 | 835 | 868 | 926 | 801 | 869 | 714 | 574 | 449 | 365 | 572 | 270 | 398 | 782 | |||

| 29) MoA | 736 | 1030 | 942 | 659 | 868 | 780 | 645 | 615 | 1196 | 1238 | 556 | 700 | 611 | 513 | 666 | 625 | 690 | 608 | 638 | 487 | 526 | 559 | 638 | 752 | 427 | 678 | 888 | 416 | ||

| 30) MoB | 674 | 948 | 851 | 568 | 880 | 728 | 595 | 511 | 1208 | 1386 | 550 | 626 | 494 | 415 | 504 | 450 | 507 | 470 | 486 | 348 | 499 | 535 | 595 | 701 | 442 | 679 | 1015 | 495 | 89 | |

| 31) Et | 1394 | 1578 | 1679 | 1543 | 1492 | 1443 | 1541 | 1649 | 1008 | 300 | 1051 | 1470 | 1517 | 1470 | 1626 | 1612 | 1685 | 1604 | 1649 | 1461 | 1357 | 1279 | 1147 | 1406 | 1015 | 847 | 751 | 607 | 888 | 1032 |

*- For populations names see figure 5.

Figure 5.

A multidimensional scaling plot of the mtDNA genetic distance matrix. Stress = 0.110 for the outer plot and 0.161 for the inner one. Populations names are: EEJ - Eastern European Jews, IqJ - Iraqi Jews, InJ - Iranian Jews, MJ - Moroccan Jews, LJ - Libyan Jews, TnJ - Tunisian Jews, BJ - Bulgarian Jews, TrJ - Turkish Jews, YJ - Yemenite Jews, EJ - Ethiopian Jews, Pa - Palestinians, It - Italians, Fr - French, Br - British, Ge - Germans, Ru - Russians, Po - Poles, Sp - Spaniards, Gr - Greeks, Tur - Turks, In - Iranians, Cy - Cypriots, Sy - Syrians, Lb - Lebanese, Jo - Jordanians, SA - Saudi-Arabians, Ye - Yemenites, Eg - Egyptians, MoA - Moroccan Arabs, MoB - Moroccan Berbers, Et - Ethiopians. Squares represent Jews and circles non-Jews. Colour indicates geographic region: red - Europe, green - Eastern Mediterranean, blue - Iran-Iraq, purpule - Arabian peninsula, yellow - North-Africa, brown - Ethiopia.

Correlations between genetic distance and geography and between genetic distance matrices based on different markers (excluding the non-Caucasoid populations Ethiopians and Ethiopian Jews) are shown in table 5. The autosomal polymorphisms have a very high correlation (0.789) with geography in contrast to the more moderate correlations of the X-chromosomal, Y-chromosomal and mtDNA polymorphisms (0.540, 0.395 and 0.641 respectively). In order to compare two competing theories regarding the origin of EEJ, their geographic distances were computed as if they originated from Italy or Israel, i.e. the great circle distances for EEJ were calculated not between Warsaw and other capitals, but between Rome or Jerusalem and other capitals. The correlation between the autosomal genetic distance matrix and geography was slightly higher, 0.804, for Rome but dropped to 0.694 for Jerusalem. Autosomal distances are much better correlated with mtDNA distances (0.826) and with X-chromosomal distances (0.732) than with Y-chromosomal distances (0.437). The correlations between the mtDNA and X-chromosomal matrices and the Y-chromosomal matrix are rather poor (0.206 and 0.241 respectively) and insignificant. When the correlations with geography were only calculated for the genetic distances of EEJ and not for the entire matrix (table 6), the same trends emerge with the autosomal correlation from Rome reaching a high of 0.926. The correlations from Jerusalem are negative for the autosomes, the X chromosome and mtDNA. The reverse is true for the Y chromosome.

Table 5.

Correlation and significance level between genetic distance matrices and between genetic distance and geography

| Autosomes | Y | mtDNA | Geography | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | |

| Autosomes* | 0.789 | 0.0001 | ||||||

| Y* | 0.437 | 0.0021 | 0.395 | 0.0038 | ||||

| mtDNA* | 0.826 | 0.0001 | 0.206 | 0.1200 | 0.641 | 0.0003 | ||

| X** | 0.732 | 0.0005 | 0.241 | 0.1399 | 0.633 | 0.0058 | 0.540 | 0.0022 |

* - Based on the 14 populations (excluding Ethiopian Jews) in the autosomal matrix

** - Based on the 10 populations (excluding Ethiopian Jews) common to all 4 matrices

r = correlation; p = significance level

Table 6.

Correlation between the genetic distances of EEJ and geography*

| Warsaw | Rome | Jerusalem | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autosomes** | 0.778 | 0.926**** | -0.149 |

| X*** | 0.781 | 0.835 | -0.685 |

| Y** | -0.613 | -0.213 | 0.556 |

| mtDNA** | 0.471 | 0.779 | -0.190 |

* - Great circle distances calculated from the three alternatives for their origin

** - Based on the 14 populations (excluding Ethiopian Jews) in the autosomal matrix

*** - Based on the 10 populations (excluding Ethiopian Jews) common to all 4 matrices

**** - When the Italians are removed, the correlation still remains very high, 0.904.

Discussion

The autosomal genetic distance analysis presented here clearly demonstrates that the investigated Jewish populations do not share a common origin. The resemblance of EEJ to Italians and other European populations portrays them as an autochthonous European population. A study conducted in a New York college in the 1920s point to the same Ashkenazi - Italian similarity on basis of physical characteristics. Freshmen were asked before they knew one another to indicate the origin of their fellow students. Forty percent of the Italians were taken to be Ashkenazi Jews, and the same percentage of Ashkenazi Jews was adjudged Italians [24]. EEJ seem to be mainly Italian (Roman) in origin, which is easily understood, considering the historical evidence presented above.

The high correlation between the autosomal genetic distances and geography and the reduced correlation when EEJ are taken to originate from the Land of Israel reinforce the European origin of EEJ. In fact the correlation of the autosomal markers with geography is higher than previously described for 49 classical markers (0.503) or ~300,000 autosomal SNPs (0.661) in Europe [25]. If for comparison, only non-Jewish European populations are included, the correlation is lower, 0.689, but still higher than the above mentioned correlations. It is also interesting to note how using the three geographic alternatives for EEJ, changes the correlation, when only European populations are included. The correlation remains almost the same, 0.679, for Rome but drops to 0.490 and 0.571 for Warsaw and Jerusalem respectively; further emphasizing the correct geographic origin of EEJ within Europe.

Biparental versus uniparental markers

At first sight it seems that there is more than one explanation for the differing results produced by the analysis of the NRY haplogroups. It thus seems possible that EEJ founder population in Rome was composed of exiled Israelite males and local Roman females. In its simple form this clearly contradicts the facts, because both the autosomal and X-chromosomal polymorphisms demonstrate that EEJ do not occupy an intermediate position between European and Middle Eastern populations, but rather a strict European one. From table 1 it is clear that Italians are as close or closer to the other Jewish populations and Palestinians as EEJ. It is possible that once the founder population was established no other males but many females joined it, thus creating a population that is almost entirely European in all genetic aspects apart from its Y chromosomes. Such phenomenon was described for the population of Antioquia, Columbia, where the autosomes point to 79% of European ancestry and only 16% of Amerindian ancestry, whereas according to mtDNA the ancestry is 90% Amerindian and only 2% European (there is also a small African component). Historical records demonstrate that local Amerindian females joined the population only at its beginning, whereas European males joined it also in later periods [26]. The suggestion that the proselyte ancestors of EEJ were almost entirely females does not however accord with what we know about conversion to Judaism [10,12,27-29].

The inference that the NRY points to a Middle Eastern origin of EEJ is erroneous not only because the Y chromosomal analysis contradicts the analyses based on the other chromosomes, and because the NRY is a single uniparental marker that does not represent the whole history of the population, but also because its smaller effective population size makes it much more vulnerable to severe genetic drift caused by demographic bottlenecks. The demographic histories of three Jewish populations exemplify how different demographic patterns make the uniparental markers more reliable for Iraqi (Babylonian) Jews and Yemenite Jews and less reliable for EEJ. Both Yemenite Jews and Iraqi Jews resemble populations from their regions of origin according to autosomal markers [1,3,30-32]. Yemenite Jews, who are usually considered a small isolate, were numerous enough to have an independent kingdom in the first centuries AD [33]. They numbered a few hundred thousand in the 12th century AD, and gradually declined; reaching only about 30-40,000 in the beginning of the 20th century [34]. Babylonian Jews numbered more than a million in the first century AD [35], and constituted the majority of the population in the area between the Euphrates and the Tigris in the 2nd-3rd centuries AD [36]. Gilbert [37] estimates that by 600 AD there were 806,000 Jews in Mesopotamia, and according to Sassoon [38] it was inhabited by about a million Jews in the 7th century. In the 14th century the estimates for Baghdad alone range from 70,000 to hundreds thousands [38]. By 1939, 11 years before their emigration, there were 91,000 Jews in Iraq [35]. In contrast, the Jewish population of the Polish-Lithuanian Kingdom (EEJ) went through the opposite process. Their history is one of founder effects, migrations, demographic bottlenecks and finally a rapid expansion. We know nothing about their number in the first millennium, but after their emigration from Italy to Western Europe it is estimated that they numbered 4,000 in 1000 and 20,000 a hundred years later [8]. In 1500 already in Eastern Europe they numbered 10,000-30,000, in 1648 230,000-450,000 and in 1764 750,000 [39-41]. In the 19th century because of the partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Kingdom and the immigrations of Jews to Central and Western Europe and America, the estimation of the number of EEJ becomes more difficult, but there is no doubt that the increase in numbers was impressive, as the number of EEJ under Russian rule alone was 5,200,000 in 1897 [41].

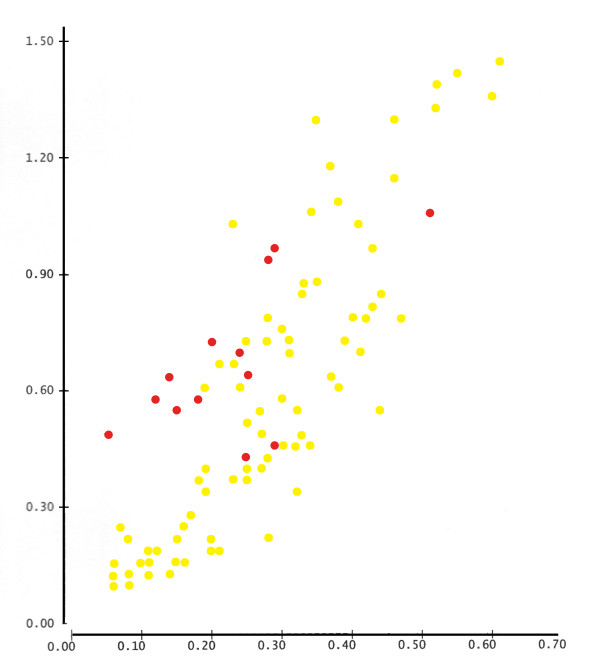

The existence of severe demographic bottlenecks in the history of EEJ has also been suggested by genetic studies of disease-causing-mutations and mtDNA [42-46]. The comparison based on this second uniparental marker, mtDNA, may help to resolve from within genetics itself the problem of the Y chromosome reliability for inferring the origin of the male ancestors of EEJ. If the European and Middle Eastern contributions to the gene pool of EEJ were female and male respectively, then comparisons based on mtDNA must place EEJ among other European populations, distant from Middle Eastern populations. The mtDNA analysis presented in this study does not place EEJ among other European populations rather their position is more intermediate and marginal, as can be seen in figure 5 and in figure 6, where autosomal distances are correlated with mtDNA distances. This lends further support to the notion that because of the unique demographic history of EEJ, their uniparental markers were subjected to stronger genetic drift than the biparental markers and thus should not be used to trace their origin.

Figure 6.

Correlation of autosomal (X axis) and mtDNA (Y axis) distances. Red circles denote EEJ. Most of the mtDNA distances of EEJ are too high relative to their autosomal distances, in contrast to most other distances (r = 0.826), attesting the greater genetic drift, to which the uniparental markers of EEJ were subjected.

The data on the Y chromosome itself also support the unreliability of the uniparental markers for discovering the origin of EEJ. Nebel et al. [47] studied haplogroup R-M17, whose frequency is ~12% in Ashkenazi Jews. By comparing the structure of the STRs network among the various Ashkenazi populations and among the various European non-Jewish populations they reached the conclusion that a single male founder introduced this haplogroup into Ashkenazi Jews in the first millennium. Behar et al. [48] write "It is striking that whereas Ashkenazi populations are genetically more diverse at both the SNP and STR level compared with their European non-Jewish counterparts, they have greatly reduced within-haplogroup STR variability ... This contrasting pattern of diversity in Ashkenazi populations is evidence for a reduction in male effective population size, possibly resulting from a series of founder events and high rates of endogamy within Europe. This reduced effective population size may explain the high incidence of founder disease mutations despite overall high levels of NRY diversity". It is unlikely that EEJ are the descendants of a single population. Admixture coupled with small effective population size and bottlenecks can create the puzzling situation we encounter in the uniparental markers. Thus smaller contributions from several populations, including possibly the original Middle Eastern Jewish population, and a major contribution from Italy combined with the unique demography of EEJ can create the current genetic picture without the need to invoke a major contribution from the Middle East, which contradicts the autosomal and X-chromosomal data.

Comments on previous studies

Some previous studies based on classical autosomal markers concluded that EEJ are a Middle Eastern population with genetic affinities to other Jewish populations. The problems with these studies have been previously discussed in detail [1]. These studies used fewer markers (mostly the less reliable antigenic markers) and failed to include European Mediterranean populations, apart from the discriminant analysis of Carmelli and Cavalli-Sforza [49], which used only four markers and contradicts the results of the later more elaborate discriminant analysis [1], and the genetic distance analysis of Livshits et al. [32], which includes a single European Mediterranean population, Spain. Despite this when a genetic distance analysis was performed, the greater similarity of EEJ to Russians and to a lesser extent to Germans more than to Non-European Jews was evident [32]. In fact Russians were more similar to EEJ than to any Non-Jewish European population in that analysis.

Recently, Cochran et al. [50] used 251 autosomal loci to calculate genetic distances and concluded that "from the perspective of a large collection of largely neutral genetic variation Ashkenazim are essentially European, not Middle Eastern". More recently, thousands of SNPs were used by Need et al. [51] to infer the relationships between Ashkenazi Jews and non-Jewish Europeans and Middle Easterners. They concluded that Ashkenazi Jews lie approximately midway between Europeans and the Middle Easterners, implying that Ashkenazi Jews may contain mixed ancestry from these two regions, and that they are close to the Adygei population from the Caucasus. However these conclusions are ill-founded, because, they used a highly selected set of SNPs, which were selected specifically for the purpose of distinguishing between Ashkenazi Jews and other populations and they inferred the origin of Ashkenazi Jews from principal components analysis (PCA), but as Tian et al. [52] show "PCA results are highly dependent on which population groups are included in the analysis. Thus, there should be some caution in interpreting these results and other results from similar analytic methods with respect to ascribing origins of particular ethnic groups'" Tian et al. [52] also published a table of paired Fst distances based on 10,500 random SNPs, which demonstrates that Ashkenazi Jews are not at all close to the Adygei population, and similarly to what is seen in table 1, their smallest distance is to Italians and then to Greeks. Unlike the assertion of Need et al. [51] on the midway position, and again similarly to what is seen in table 1, Italians and Greeks are closer to the Middle Eastern populations than Ashkenazi Jews.

The same phenomenon is seen in the table of Fst distances of Atzmon et al. [53]. North Italians (Bergamo and Tuscany) are a little closer to the Jewish and Middle Eastern populations than Ashkenazi Jews. The Italians from Tuscany (surprisingly the sample from Bergamo was not used) in Behar et al. [54] are also closer to the Jewish and Middle Eastern populations than Ashkenazi Jews. The Italians from Tuscany are in fact the closest population to Ashkenazi Jews in Behar et al. [54]. There is one sample that is apparently a little closer, what they call Sephardic Jews. Unfortunately this sample is composed of two populations, Turkish Jews and Bulgarian Jews, which should have been studied separately like all other Jewish populations. Bulgarian Jews have been shown in the past based on autosomal classical markers to be closer to EEJ than to populations with Sephardic ancestry and considering their history it was concluded that the Ashkenazi component in their gene pool is at least as large or even larger that the Sephardic component [1]. From both The current study and those of Atzmon et al. [53] and Behar et al. [54] it can be seen that the only Jewish populations that are as close to Ashkenazi Jews as non-Jewish Europeans are those with a significant Sephardic (The descendants of the Jews who were expelled from the Iberian peninsula at the end of the 15th century) component in their gene pool. It is not possible at this stage to say what is the source of this resemblance, since we don't know what is the origin of Sephardic Jews, but considering all the genetic affinities of both groups it likely stems from Sephardic Jews being the descendants of converts in the Mediterranean basin rather than from a common Jewish origin in the Land of Israel. When one compares the autosomal distances of EEJ (current study) or Ashkenazi Jews (in Atzmon et al. [53] and Behar et al. [54]) from the Jewish populations that were investigated in the current study, Iraqi, Iranian, Moroccan, Yemenite and Ethiopian Jews, one finds perfect agreement. EEJ or Ashkenazi Jews are much closer to non-Jewish Europeans than to these Jewish populations in all three studies.

The studies of Atzmon et al. [53] and Behar et al. [54] are based on 164,894 and 226,839 SNPs respectively. While this impressive number reduces the errors of the distances that stem from the number of markers, the errors that stem from sampling only a small number of individuals are much larger in these studies, where sample sizes can be as small as 2-4 individuals. The effect of these errors can be seen in table 7. Despite the small number of markers the current matrix has the highest correlation with geography. Moreover it has a higher correlation with each of the two other matrices than the two of them have with each other. The high correlations between the current matrix and the other two attest for the robustness of the autosomal genetic distances in this study. The lower correlation between the two matrices, which are based on more than 150,000 SNPs, is surprising and even more so, if we remember that the four non-Jewish populations are represented by exactly the same individuals taken from the Human Genome Diversity Panel (HGDP). It is likely then that sampling more individuals, which represent more of the variation of the investigated populations, is far more important than typing many markers. It is also possible that the typing error rates of genome-wide microarray studies are much higher, as demonstrated by the genotyping errors that were discovered in 7 out of 29 (24%) reexamined SNPs [55]. It seems therefore, that good characterization of the genetic relationships between populations can be achieved by a small number of good unique-event-polymorphisms.

Table 7.

Comparison of the correlations of the three autosomal genetic distance matrices*

| Current Study | Atzmon et al. | Geography** | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | r | p | r | p | |

| Current Study | 0.561 | 0.0015 | ||||

| Atzmon et al. 2010 | 0.872 | 0.0003 | 0.482*** | 0.0192 | ||

| Behar et al. 2010 | 0.852 | 0.0012 | 0.788 | 0.0029 | 0.437**** | 0.0351 |

* - Based on the 7 populations common to all 3 studies

** - Great circle distances for EEJ or Ashkenazi Jews calculated from Rome (in all cases this was the highest correlation)

*** - Great circle distances for Italians calculated from Parma

**** - Great circle distances for Italians calculated from Florence

r = correlation; p = significance level

Conclusions

EEJ are Europeans probably of Roman descent who converted to Judaism at times, when Judaism was the first monotheistic religion that spread in the ancient world. Any other theory about their origin is not supported by the genetic data. Future studies will have to address their genetic affinities to various Italian populations and examine the possibility of other components both European and Non-European in their gene pool.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Reviewers' comments

Reviewer's report 1

Damian Labuda, Pediatrics Department, Montreal University Sainte-Justine Hospital Research Center, Montreal, PQ Canada (nominated by Jerzy Jurka, Genetic Information Research Institute, Mountain View, California USA).

The author compiled and reanalyzed the data on autosomal and sex chromosomes polymorphisms collected by different laboratories on different Jewish and West-Eurasiatic populations. His analysis indicates much greater European component of Eastern European Jews, EEJ (essentially Ashkenazim) than of other Jewish groups. Moreover the analysis points to Italians as the closest population to EEJ.

The question is how to interpret this evidence. Imperial Rome was a very cosmopolitan city culturally and genetically diverse. To what extent a sample of contemporary Italians preserves the genetic link to its population? It can simply reflect a mixture of historical influences from different centers around the Mediterranean Sea. We should thus keep in mind that the Italian connection may simply indicate Southern European and Mediterranean links with the latter including Middle Eastern roots.

Interestingly, this analysis that is based on a limited number of markers provided results that are very similar to a paper of Atzmon and colleagues, published five days ago in the American Journal of Human Genetics, and based on the microarray-based genotyping genome of wide distributed markers. I would like the author to comment on this paper in the context of his findings and his thoughts and reflections on the origin of Jewish Diasporas. Should we go back to the single locus analyses, as in the case of uniparentally transmitted markers, but targeting one by one different individual segments of the nuclear genome? Perhaps, in this way we could partition and identify genetic ancestries of different populations, which due to their history of relative isolation, are considered as genetically homogenous.

The author refers to Sangvi's G2 as the most appropriate distance metrics. Could you make it more clear when this metric was used and when that of Reynolds (only to produce a tree?).

Author's response

The historical sources listed above show that conversion to Judaism was common in ancient Rome among all ranks of the Roman society including the imperial families. It is thus unlikely that the original Roman population did not constitute a significant portion of the proselytes. What else can explain the resemblance of EEJ to a general sample of Italians in this study and to more local samples in the two array studies [53,54]? In all three studies the genetic affinities of the Ashkenazim are very similar to the affinities of the Italians, with the Ashkenazim usually being a bit more distant from the other populations, as can be expected from a population that underwent a stronger genetic drift. It is thus unlikely that the Ashkenazim are a mixture of people from different places in the Mediterranean basin, unless current-day Italians themselves not only have absorbed foreign genetic contributions, but actually constitute such a mixture, and this seems unlikely as well. The very high correlation (0.926) between the genetic distances of EEJ and geographic distances, when the latter are calculated from Rome, also supports the origin of EEJ from Italy or its vicinity and not merely from the Mediterranean basin. The similarity to Italians was also evident when several Italian populations from different provinces were included in a comparison based on classical autosomal markers. Most Italian populations were closer to EEJ than all other populations (data not shown).

My comments on the papers by Atzmon et al. [53] and Behar et al. [54] are in the discussion. Studying autosomal haplotypes will indeed contribute to revealing the ancestries of populations, but in order to gain meaningful insights one ought to study at least several loci and ensure that sample sizes are adequate, this may entail more effort than studying single SNPs, and I am not sure that the affinities between the populations are going to be depicted more accurately. I changed the phrasing in Methods to make it clearer that the formula of Reynolds et al. was only used for the calculation of the tree.

Reviewer's report 2

Kateryna Makova, Department of Biology, Penn State University, Pennsylvania USA.

This is an interesting manuscript that presents intriguing results. I have only a few comments:

1. The introduction is very short, while the discussion is lengthy. I suggest moving parts of the Discussion to the Introduction.

2. Some of the statements in the Discussion are too strong. I disagree with statements about "erroneous Y chromosomal genetic distances", "both uniparental markers should not be used to trace their origin", "uniparental markers being unreliable". The author should modify them.

Author's response

I moved the paragraph on the history of EEJ to the Introduction. The current revised version of the paper includes a new comparison based on mtDNA. I maintain that it adds more weight to my assertion that the uniparental markers should not be used to trace the origin of EEJ. In no way did I mean that the uniparental markers are always unreliable; to clarify it I modified the relevant sentence in the discussion. Indeed from the demographic examples that I give in the Discussion, it seems that the uniparental markers can be used to study the origins of Iraqi Jews and Yemenite Jews.

Reviewer's report 3

Qasim Ayub, The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, UK (nominated by Dan Graur, Department of Biology and Biochemistry, University of Houston, Houston, USA).

The paper by Zoossmann-Diskin entitled 'The origin of Eastern European Jews revealed by autosomal and sex chromosomal polymorphisms' explores autosomal and sex chromosomal polymorphisms in six Jewish populations using previously published and additional unpublished data. The author concludes that the Jewish populations examined do not share a common origin and that Eastern European Jews are closer to the Italian population.

My major concern is the choice of markers and populations used in this study. The author has analyzed 17 autosomal loci, including 9 polymorphic protein electrophoretic variants in which the genotype was assumed. Although phenotypes often do correlate with genotypes assuming that they do can lead to erroneous results. Of the remaining 8 it is unclear whether the same samples were genotyped as the sample numbers for each locus vary widely (Supplementary Tables 2-4).

The author also uses Y hapologroup frequencies and shows a multidimensional scaling plot of Y chromosomal genetic distance matrix. However, the supplementary data (Supplementary Table 5) lists an outdated nomenclature for Y haplogroups as the M78 marker is no longer considered part of haplogroup E3b1. It would be more appropriate to list which markers are used to designate the haplogroups to ensure that they are comparable. In addition, the haplogroups that are selected for these analyses do not provide phylogenetic resolution to reliably detect male genetic sub-structure within the Middle East. The omission of recent mtDNA studies (Behar et al., 2008, PLoS One 3:e2062) is surprising as is the use of a single X chromosomal locus (DYS44) to make broad conclusions about genetic relatedness.

Current evidence, supported more recently by two major studies carried out on Jewish populations (Atzmon et al., Am J H Genetics 86:850-859; Behar et al., Nature doi:10.1038) using a much larger dataset clearly demonstrate a common genetic thread linking the diverse Mizrahi, Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jewish populations with the populations from the Levant and Middle East. The Ashkenazi show a European component but this is shared with many Eastern and Southern Europeans populations. These studies contradict the author's conclusion and demonstrate the power of using unbiased markers and host populations in corresponding geographic regions to address issues such as genetic relatedness among Jewish and non-Jewish populations

Author's response

I am not sure what Dr Ayub means by "assumed", but I suspect that he means something like the relationships between phenotype and genotype in certain blood groups, in which one (or more) allele is dominant over the other and the gene frequencies of the alleles have to be inferred from the phenotypes assuming Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. In such cases there may indeed be errors in the gene frequencies. Protein electrophoretic markers are completely different. Nothing is inferred! As mentioned in Methods all the protein electrophoretic markers in this study represent a SNP at the DNA level. This SNP causes an amino acid change that can be detected at the protein level. Both alleles are directly viewed on the gel in the same way as both alleles of an RFLP are directly viewed on the gel. Gene frequencies are determined in both cases by simple gene counting and the error rate in protein electrophoresis is no greater than in DNA studies. There is no need to type the same samples for all the polymorphisms, because the unit of study is the population, not the individual. One can use polymorphisms typed by different researchers using different samples and combine them to create a genetic profile of each population. Typing all the polymorphisms on the same sample does not add more credibility to the study. Indeed the renowned works that employed classical autosomal markers to portray the genetic affinities of human populations were based on many different samples typed by many different researchers [56,57].

The nomenclature in the Y chromosome supplementary table has been updated. Following the publication of the study by Behar et al. [54] it was possible to add more Jewish populations to the Y chromosome analysis and increase the number of chromosomes for the Jewish populations. This increase has come however at the expense of resolution, because Behar et al. [54] used fewer haplogroups in their analysis. Consequently the number of haplogroups was reduced from 15 in the original version to 14 in this revised version. I would have been happier if the available data on the Jewish populations had enabled greater resolution to reliably detect male genetic sub-structure within the Middle East, but since this work deals with the genetic affinities of EEJ, the current level is sufficient. The work of Behar et al. from 2008 was instrumental in creating the mtDNA matrix as can be seen in table 7 in Additional file 1. There was no need to cite it previously, as it did not contain any genetic distance analysis that could further clarify the origin of EEJ. I am surprised at Dr Ayub's surprise at the use of a single X chromosomal locus. It would have been better to use many X chromosomal loci, but even the use of single loci is advantageous, as I am sure even Dr Ayub would agree regarding the two other single loci that I use, the non-recombining Y chromosome (NRY) and mtDNA.

As written in the Discussion the genetic distance matrices of Atzmon et al. [53] and Behar et al. [54] do not contradict my results, but reinforce them. I completely reject Dr Ayub's claim that the markers or populations I used are biased in anyway, and I let the reader judge, where exactly the bias lies.

Supplementary Material

Allele frequencies tables, Tables S1-S7. The file contains seven tables that give the allele frequencies of the employed polymorphisms.

References

- Zoossmann-Diskin A, Joel A, Liron M, Kerem B, Shohat M, Peleg L. Protein electrophoretic markers in Israel: compilation of data and genetic affinities. Ann Hum Biol. 2002;29:142–175. doi: 10.1080/03014460110058971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonné-Tamir B, Zoossmann-Diskin A, Teicher A, Oppenheim A, Nevo S. In: Isolation migration and health. Roberts DF, Fujiki N, Torizuka K, editor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1992. Genetic distance analyses in Israeli groups using classical markers and DNA polymorphisms in the β-globin gene; pp. 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Zoossmann-Diskin A, Gazit E, Peleg L, Shohat M, Turner D. Thrombophilic polymorphisms in Israel. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2008;41:230–233. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankory Z. In: Genetic diseases among Ashkenazi Jews. Goodman RM, Motulsky AG, editor. New York: Raven Press; 1979. Origins and history of Ashkenazi Jewry (8th to 18th century) pp. 19–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hendelssmann Y. In: The History of the people of Israel. Shavit S, Shamir I, editor. Givataim, Israel: Massada; 1985. The Jewish centre in Ashkenaz in the 10-13th centuries; pp. 72–73. (in Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Renan E. Le judaÏsme comme race et comme religion. Paris: Ancienne Maison Michel Lévy Frères; 1883. [Google Scholar]

- Ashdy L. In: Encyclopedia of social sciences. Knaani D, editor. Vol. 1. Tel-Aviv: Sifriat-Poalim; 1970. Germany, Jews; pp. 849–862. (in Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Kriegel M. In: A historical atlas of the Jewish people. Barnavi E, editor. London: Hutchinson; 1992. The beginnings of European Jewry, 500-1096; pp. 78–79. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern I. In: The Jews, their history, culture and religion. Finkelstein L, editor. Vol. 1. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers; 1960. The Jews in Eastern Europe (From Ancient Times until the Partitions of Poland, 1772-1795) pp. 287–319. [Google Scholar]

- Rapaport U. PhD thesis. The Hebrew University; 1965. Jewish religious propaganda and proselytism in the period of the second commonwealth. (in Hebrew with an English abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Eilat T. MA thesis. Tel-Aviv University; 1979. The Jewish community in pagan Rome from its beginning in times of the republic till Christianity became a recognized religion of the Roman Empire. (in Hebrew with an English abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Feldman LH. In: The Diaspora in the Hellenistic-Roman world. Stern M, editor. The Society For The Publication Of The History Of The Jewish People, Israel; 1983. Proselytism and syncretism; pp. 188–207. (in Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Meroz N. MA thesis. Tel-Aviv University; 1992. Proselytism in the Roman Empire in the first centuries AD. (in Hebrew with an English abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Zoossmann-Diskin A, Swinburne S, Shohat M, Peleg L, Gazit E, Turner D. Typing classical polymorphisms by real-time PCR: analysis of the GPT and ALAD protein polymorphisms in the Jewish populations. Am J Hum Biol. 2008;20:490–492. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainwright BJ, Scambler PJ, Schmidtke J, Watson EA, Law HY, Farrall M, Cooke HJ, Eiberg H, Williamson R. Localization of cystic fibrosis locus to human chromosome 7cen-q22. Nature. 1985;318:384–385. doi: 10.1038/318384a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White R, Woodward S, Leppert M, O'connell P, Hoff M, Herbst J, Lalouel JM, Dean M, Vande Woude G. A closely linked genetic marker for cystic fibrosis. Nature. 1985;318:382–384. doi: 10.1038/318382a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoossmann-Diskin A, Gazit E, Peleg L, Shohat M, Turner D. 844ins68 in the cystathionine beta-synthase gene in Israel and review of its distribution in the world. Anthropol Anz. 2004;62:147–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigat B, Hubert C, Corvol P, Soubrier F. PCR detection of the insertion/deletion polymorphism of the human angiotensin converting enzyme gene (DCP1) (dipeptidyl carboxypeptidase 1) Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:1433. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.6.1433-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goltsov AA, Eisensmith RC, Woo SL. Detection of the XmnI RFLP at the human PAH locus by PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:927. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.4.927-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorde LB. In: Current developments in anthropological genetics. Mielke JH, Crawford MH, editor. Vol. 1. New York: Plenum Press; 1980. The genetic structure of subdivided human populations; pp. 135–208. [Google Scholar]

- Sanghvi LD. Comparison of genetical and morphological methods for a study of biological differences. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1953;11:385–404. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330110313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M. Genetic distance between populations. American Naturalist. 1972;106:283–292. doi: 10.1086/282771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds J, Weir BS, Cockerham CC. Estimation of the Coancestry Coefficient: Basis for a Short-Term Genetic Distance. Genetics. 1983;105:767–779. doi: 10.1093/genetics/105.3.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herskovits MJ. In: The Jews, their history, culture and religion. Finkelstein L, editor. Vol. 2. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers; 1960. Who are the Jews? pp. 1489–1507. [Google Scholar]

- Lao O, Lu TT, Nothnagel M, Junge O, Freitag-Wolf S, Caliebe A, Balascakova M, Bertranpetit J, Bindoff LA, Comas D, Holmlund G, Kouvatsi A, Macek M, Mollet I, Parson W, Palo J, Ploski R, Sajantila A, Tagliabracci A, Gether U, Werge T, Rivadeneira F, Hofman A, Uitterlinden AG, Gieger C, Wichmann HE, Ruther A, Schreiber S, Becker C, Nurnberg P, Nelson MR, Krawczak M, Kayser M. Correlation between genetic and geographic structure in Europe. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1241–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedoya G, Montoya P, Garcia J, Soto I, Bourgeois S, Carvajal L, Labuda D, Alvarez V, Ospina J, Hedrick PW, Ruiz-Linares A. Admixture dynamics in Hispanics: a shift in the nuclear genetic ancestry of a South American population isolate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7234–7239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508716103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braude WG. Jewish proselyting in the first five centuries of the common era, the age of the Tannaim and Amoraim. Menasha, WI: The George Banta Publishing Company; 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberger BJ. Proselytism in the Talmudic period. New York: Ktav Publishing House; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom JR. Conversion to Judaism: from the biblical period to the present. Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bonné-Tamir B. In: Genetic Microdifferentiation in Human and other Animal Populations: Occasional Papers in Anthropology No. 1. Ahuja YN, Neel JV, editor. Delhi: Indian Anthropological Association; 1985. Oriental Jewish communities and their genetic relationships with South-West Asian populations; pp. 153–170. [Google Scholar]

- Bonné-Tamir B, Zoossmann-Diskin A, Teicher A. In: Genetic diversity among Jews: Diseases and markers at the DNA level. Bonné-Tamir B, Adam A, editor. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992. Genetic diversity among Jews reexamined: preliminary analyses at the DNA level; pp. 80–94. [Google Scholar]

- Livshits G, Sokal RR, Kobyliansky E. Genetic affinities of Jewish populations. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;49:131–146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Zeev I. The Jews in Arabia. Jerusalem: Achiassaf; 1970. (in Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Ashdy L. In: Encyclopedia of social sciences. Knaani D, editor. Vol. 5. Tel-Aviv: Sifriat-Poalim; 1970. Yemen, Jews; pp. 853–854. (in Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Baron SW. In: Encyclopaedia Judaica. Roth C, Wigoder G, editor. Vol. 13. Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House; 1971. Population; pp. 866–903. [Google Scholar]

- Grets T. History of the Jews. Hebrew. Tel-Aviv: Izreel Publishing House; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert M. Jewish history atlas. Hebrew. Jerusalem: Edanim Publishers (By arrangement with Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London); 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Sassoon DS. A history of the Jews in Baghdad. Letchworth, Great Britain; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Baron SW. A social and religious history of the Jews. XVI. New York: Columbia University Press; 1976. Poland-Lithuania 1500-1650. [Google Scholar]

- Polonsky A. In: The Jews in old Poland, 1000-1795. Polonsky A, Basista J, Link-Lenczowski A, editor. London: IB Tauris & Co Publishers; 1993. Introduction; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Stampfer S. In: The broken chain, Polish Jewry through the ages. Bartal I, Gutman I, editor. Jerusalem: The Zalman Shazar Center; 1997. Population growth and emmigration of the Polish-Lithuanian Jewry in the 16-19th centuries; pp. 263–285. (in Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Diaz GA, Gelb BD, Risch N, Nygaard TG, Frisch A, Cohen IJ, Miranda CS, Amaral O, Maire I, Poenaru L, Caillaud C, Weizberg M, Mistry P, Desnick RJ. Gaucher disease: the origins of the Ashkenazi Jewish N370S and 84GG acid beta-glucosidase mutations. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:1821–1832. doi: 10.1086/302946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch A, Colombo R, Michaelovsky E, Karpati M, Goldman B, Peleg L. Origin and spread of the 1278insTATC mutation causing Tay-Sachs disease in Ashkenazi Jews: genetic drift as a robust and parsimonious hypothesis. Hum Genet. 2004;114:366–376. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-1072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risch N, Tang H, Katzenstein H, Ekstein J. Geographic distribution of disease mutations in the Ashkenazi Jewish population supports genetic drift over selection. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:812–822. doi: 10.1086/373882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slatkin M. A population-genetic test of founder effects and implications for Ashkenazi Jewish diseases. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:282–293. doi: 10.1086/423146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behar DM, Hammer MF, Garrigan D, Villems R, Bonné-Tamir B, Richards M, Gurwitz D, Rosengarten D, Kaplan M, Della Pergola S, Quintana-Murci L, Skorecki K. MtDNA evidence for a genetic bottleneck in the early history of the Ashkenazi Jewish population. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004;12:355–364. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebel A, Filon D, Faerman M, Soodyall H, Oppenheim A. Y chromosome evidence for a founder effect in Ashkenazi Jews. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005;13:388–391. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behar DM, Garrigan D, Kaplan ME, Mobasher Z, Rosengarten D, Karafet TM, Quintana-Murci L, Ostrer H, Skorecki K, Hammer MF. Contrasting patterns of Y chromosome variation in Ashkenazi Jewish and host non-Jewish European populations. Hum Genet. 2004;114:354–365. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-1073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmelli D, Cavalli-Sforza LL. The genetic origin of the Jews: a multivariate approach. Hum Biol. 1979;51:41–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran G, Hardy J, Harpending H. Natural history of ashkenazi intelligence. J Biosoc Sci. 2006;38:659–693. doi: 10.1017/S0021932005027069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Need AC, Kasperaviciute D, Cirulli ET, Goldstein DB. A genome-wide genetic signature of Jewish ancestry perfectly separates individuals with and without full Jewish ancestry in a large random sample of European Americans. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian C, Kosoy R, Nassir R, Lee A, Villoslada P, Klareskog L, Hammarstrom L, Garchon HJ, Pulver AE, Ransom M, Gregersen PK, Seldin MF. European Population Genetic Substructure: Further Definition of Ancestry Informative Markers for Distinguishing Among Diverse European Ethnic Groups. Mol Med. 2009;15:371–383. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2009.00094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atzmon G, Hao L, Pe'er I, Velez C, Pearlman A, Palamara PF, Morrow B, Friedman E, Oddoux C, Burns E, Ostrer H. Abraham's children in the genome era: major Jewish diaspora populations comprise distinct genetic clusters with shared Middle Eastern Ancestry. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:850–859. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behar DM, Yunusbayev B, Metspalu M, Metspalu E, Rosset S, Parik J, Rootsi S, Chaubey G, Kutuev I, Yudkovsky G, Khusnutdinova EK, Balanovsky O, Semino O, Pereira L, Comas D, Gurwitz D, Bonne-Tamir B, Parfitt T, Hammer MF, Skorecki K, Villems R. The genome-wide structure of the Jewish people. Nature. 2010;466:238–242. doi: 10.1038/nature09103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y, Zhang X, Huang N, Daly A, Gillson CJ, Macarthur DG, Yngvadottir B, Nica AC, Woodwark C, Chen Y, Conrad DF, Ayub Q, Mehdi SQ, Li P, Tyler-Smith C. Population differentiation as an indicator of recent positive selection in humans: an empirical evaluation. Genetics. 2009;183:1065–1077. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.107722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli-Sforza LL, Piazza A. Human genomic diversity in Europe: a summary of recent research and prospects for the future. Eur J Hum Genet. 1993;1:3–18. doi: 10.1159/000472383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli-Sforza LL, Menozzi P, Piazza A. The history and geography of human genes. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Weber W. Untersuchungen von in Deutschland lebenden Türken in 23 Blutgruppensystemen; Bedeutung für die Biostatistik. Das Ärztliche Laboratorium. 1983;29:171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Walter H, Gölge M, Aksoy M, Bermik E, Sivasli A. Genetic serum protein markers (HP, GC, TF, PI) in four Turkish population samples. Int J Anthropol. 1992;7:27–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02447867. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brega A, Scacchi R, Cuccia M, Kirdar B, Peloso G, Corbo RM. Study of 15 protein polymorphisms in a sample of the Turkish population. Hum Biol. 1998;70:715–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiakalos G, Walter H, Hilling M, Schaarschmidt L. Investigations on the distribution of genetic polymorphisms in Greece. 2. Serum protein polymorphisms. Anthropol Anz. 1981;39:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiakalos G, Walter H, Hilling M. Investigation on the distribution of genetic polymorphisms in Greece. 3. Red cell enzyme polymorphisms and genetic distances. Anthropol Anz. 1981;39:244–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouvatsi A, Triantaphyllidis CD. Gc and Tf subtypes in Greece. Hum hered. 1987;37:62–64. doi: 10.1159/000153679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hundrieser J, Bremer S, Peinemann F, Stuhrmann M, Hoffknecht N, Wulf B, Schmidtke J, Reiss J, Maass G, Tümmler B. Frequency of the F508 deletion in the CFTR gene in Turkish cystic fibrosis patients. Hum Genet. 1990;85:409–410. doi: 10.1007/BF02428283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devoto M, De Benedetti L, Seia M, Piceni Sereni L, Ferrari M, Bonduelle ML, Malfroot A, Lissens W, Balassopoulou A, Adam G, Loukopoulos D, Cochaux p, Vassart G, Szibor R, Hein J, Grade K, Berger W, Wainwright B, Romeo G. Haplotypes in cystic fibrosis patients with or without pancreatic insufficiency from four European populations. Genomics. 1989;5:894–898. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(89)90131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber J, Aulehla-Scholz C, Kaiser R, Eigel A, Neugebauer M, Horst J, Olek K. Cystic fibrosis: typing 89 German families with linked DNA probes. Hum Genet. 1988;81:54–56. doi: 10.1007/BF00283729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tummler B, Aschendorff A, Darnedde T, Fryburg K, Maass G, Hundrieser J. Marker haplotype association with growth in German cystic fibrosis patients. Hum Genet. 1990;84:267–273. doi: 10.1007/BF00200573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidtke J, Krawczak M, Schwartz M, Alkan M, Bonduelle M, Bühler E, Chemke M, Darnedde T, Domagk J, Engel W, Frey D, Fryborg K, Halley D, Hundrieser J, Ladanyi L, Libaers I, Lissens W, Mächler M, Malik NJ, Morreau J, Neubauer V, Oostra B, Pape B, Poncin JE, Schinzel A, Simon P, Trefz FK, Tümmler B, Vassart G, Voss R. Linkage relationships and allelic associations of the cystic fibrosis locus and four marker loci. Hum Genet. 1987;76:337–343. doi: 10.1007/BF00272441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean M, Amos JA, Lynch J, Romeo G, Devoto M, Ward K, Halley D, Oostra B, Ferrari M, Russo S, Weir BS, Finn PB, Collins FS, Iannuzzi MC. Prenatal diagnosis and linkage disequilibrium with cystic fibrosis for markers surrounding D7S8. Hum Genet. 1990;85:275–278. doi: 10.1007/BF00206745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudet A, Bowcock A, Buchwald M, Cavalli-Sforza L, Farrall M, King MC, Klinger K, Lalouel JM, Lathrop G, Naylor S, Ott J, Tsui LC, Wainwright B, Watkins P, White R, Williamson R. Linkage of cystic fibrosis to two tightly linked DNA markers: joint report from a collaborative study. Am J Hum Genet. 1986;39:681–693. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay M, Williamson R, Estivill X, Wainwright BJ, Ho MF, Halford S, Kere J, Savilahti E, de la Chapelle A, Schwartz M, Super M, Farndon P, Harding C, Meredith L, Al-Jader L, Ferec C, Claustres M, Casais T, Nunes V, Gasparini P, Savoia A, Pignatti PP, Novelli G, Bennarelli M, Dallapicola B, Kalaydjieva L, Scambler PJ:. Haplotype analysis to determine the position of a mutation among closely linked DNA markers. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2:1007–1014. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.7.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A, Beards F, Mathew C. Mutation analysis at the cystic fibrosis locus in the British population. Hum Genet. 1990;85:408–409. doi: 10.1007/BF02428282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh I, Curtis A, Lorenzo ML, Keston M, Gilfillan AJ, Morris G, Brock DJ. The haplotype distribution of the delta F508 mutation in cystic fibrosis families in Scotland. Hum Genet. 1990;85:419–420. doi: 10.1007/BF02428290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mornet E, Simon-Bouy B, Serre JL, Estivill X, Farrall M, Williamson R, Boue J, Boue A. Genetic differences between cystic fibrosis with and without meconium ileus. Lancet. 1988;1:376–378. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(88)91180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidaud M, Kitzis A, Ferec C, Bozon D, Dumur V, Giraud G, David F, Pascal O, Auvinet M, Morel Y, Andre J, Chomel JC, Saleun JP, Farriaux JP, Roussel P, Labbé A, Dastugue B, Lucotte G, Monnier N, Foucaud P, goossens M, Feingold J, Kaplan JC. Confirmation of linkage disequilibrium between haplotype B (XV-2c, allele 1;KM-19, allele 2) and cystic fibrosis allele in the French population. Hum Genet. 1989;81:183–184. doi: 10.1007/BF00293899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serre JL, Simon-Bouy B, Mornet E, Jaume-Roig B, Balassopoulou A, Schwartz M, Taillandier A, Boué J, Boué A. Studies of RFLP closely linked to the cystic fibrosis locus throughout Europe lead to new considerations in populations genetics. Hum Genet. 1990;84:449–454. doi: 10.1007/BF00195818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferec C, Verlingue C, Parent P. Desequilibre de liaison et marqueurs de l'ADN associes au gene de la fibrose kystique. J Genet Hum. 1989;37:407–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranov VS, Ivashchenko TE, Gorbunova VN, Voronina OV, Gaĭtskhoki VS, Gol'tsov AA, Kaboev OK, Shvarts EI, Berlin YuA, Livshits LA, Buzhievskaya TI, Venozhinskis MT, Sokolov BP, Kalinin VN, Orlov AV, Romanenko OP, Luk'yanenko AN, Kapranov NI, Rachinskii SV. Allele polymorphism of the DNA loci MET, D7S8, D7S23, linked to the cystic fibrosis gene in some populations of the USSR, in high risk families and in cystic fibrosis patients. Genetika. 1991;27:113–121. (in Russian) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voronina OV, Baranov VS, Gaitskhoki VS, Gorbunova VN, Ivashchenko TE, Shvartsman AL. Polymorphism of nucleotide sequences of human genomic DNA linked to a mucoviscidosis locus. Mol Gen Mikrobiol Virusol. 1990. pp. 14–17. (in Russian) [PubMed]

- Bal J, Maciejko D, Buława E, Mazurczak T. Zastosowanie sond molekularnych DNA w diagnostyce mukowiscydozy--analiza polimorfizmu dlugosci fragmentow restrykcyjnych (RFLP) w 22 rodzinach wysokiego ryzyka. Pol Tyg Lek. 1992;47:215–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akar N, Akar E, Misirlioğlu M, Avcu F, Yalçin A, Cin S. Search for genetic factors favoring thrombosis in Turkish population. Thromb Res. 1998;92:79–82. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(98)00113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akar N, Misirlioğlu M, Akar E, Avcu F, Yalçin A, Sözüöz A. Prothrombin gene 20210 G-A mutation in the Turkish population. Am J Hematol. 1998;58:249. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8652(199807)58:3<249::AID-AJH20>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balta G, Gürgey A. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T mutation in Turkish patients with thrombosis. Turk J Pediatr. 1999;41:197–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gürgey A, Mesci L. The prevalence of factor V Leiden (1691 G-- > A) mutation in Turkey. Turk J Pediatr. 1997;39:313–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozbek U, Tangün Y. Frequency of factor V Leiden (Arg506Gln) in Turkey. Br J Haematol. 1997;97:504–505. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.d01-3343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]