Abstract

In this paper, we explore how the stigmatization of place is transported to new destinations and negotiated by those who carry it. Additionally, we discuss the implications of ‘spatial stigmatization’ for the health and well-being of those who relocate from discursively condemned places such as high-poverty urban neighborhoods. Specifically, we analyze in-depth interviews conducted with 25 low-income African American men and women who have moved from urban neighborhoods in Chicago to predominantly white small town communities in eastern Iowa. These men and women, who moved to Iowa in the context of gentrification and public housing demolition, describe encountering pervasive stigmatization that is associated not only with race and class, but also with defamed notions of Chicago neighborhoods.

Keywords: stigma, race, poverty, residential mobility, health inequality

Introduction

A large body of literature has documented the profound negative health consequences associated with residence in racially segregated, economically disadvantaged and socially marginalized urban neighborhoods (Acevedo-Garcia, Lochner, Osypuk, & Subramanian, 2003; Williams & Collins, 2001). The bulk of this research has considered these negative health consequences as the result of physical proximity to unhealthy phenomena, limited access to health promoting resources or exposure to socially harmful patterns that emerge under conditions of long-term economic deprivation (Ellen & Turner, 1997; Entwisle, 2007; Sampson, Morenoff, & Gannon-Rowley, 2002; W. J. Wilson, 1987). In addition to studies that have focused on the conditions within high-poverty neighborhoods, others have considered how the social construction and stigmatization of ‘the ghetto’ itself affects the health and well-being of its residents (Kelaher, Warr, Feldman, & Tacticos, 2010; Macintyre, Ellaway, & Cummins, 2002; Popay, Thomas, Williams, Bennett, Gatrell, & Bostock, 2003; Wacquant, 2007, 2008; Wakefield & McMullan, 2005). As Wacquant points out, urban neighborhoods are not only physically bounded spaces, they are also symbolic places onto which powerful meanings are loaded. Urban “ghettos” are both spatial representations of deeply rooted structural inequalities and also a mechanism by which this inequality is reinforced, not only through geographic marginalization but also through “discourses of vilification” that are perpetuated in popular and political discourse (Wacquant, 2007). As discussed by some analysts (Goode & Maskovsky, 2001; Wacquant, 1997) this vilification of high-poverty urban areas is also perpetuated in a wide range of academic scholarship that has emphasized the presumed social pathologies of an urban ‘underclass’. According to Wacquant (2007), residents of such vilified spaces are often marked not only by the stigma of race and class, but also by a “blemish of place” that, much like many other forms of stigma, “reduces them from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one” (Goffman, 1963).

Only a small body of literature has considered the ways that residents of such “tainted” places experience, manage and resist this ‘spatial stigma’ (Gordon 1991; Neckerman & Kirschenman, 1991; Wacquant, 2007, 2008) and even fewer studies have explored the implications of spatial stigma for health and well-being (Kelaher et al., 2010; Popay et al., 2003; Stead, MacAskill, MacKintosh, Reece, & Eadie, 2001; Wakefield & McMullan, 2005). We know even less about how spatial stigma affects those individuals who relocate from discursively condemned neighborhoods. In this paper, we draw on qualitative interviews among a group of migrants experiencing significant spatial stigma that is associated with their former residence in high-poverty urban areas. In our analysis, we interrogate three questions: to what extent do the bodies of migratory people become markers of the very places they leave behind? What strategies do persons experiencing spatial stigma employ in order to shed discrediting marks of place? And what are the consequences of spatial stigma for health and well-being?

These questions are particularly relevant in the context of recent programs and policies that seek to ameliorate urban poverty and its consequences through poverty deconcentration (Goetz 2001) or social-mixing initiatives (Musterd & Andersson 2005). In the European context, such policy approaches have primarily emphasized the construction of mixed-tenure communities where home owners and renters live side by side (Musterd & Andersson 2005). In contrast, several recent US initiatives have promoted the mobility of low-income households. The most well-known of these initiatives is the US Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Moving to Opportunity Program (MTO), which between the years 1994 and 1998, provided over 3,000 volunteer public housing residents in five cities with vouchers and the opportunity to leave public housing. MTO was not only a housing program, but also a randomized experiment that has provided a wealth of data on relocation from public housing. Over a 10 year follow-up period, the experiences and outcomes of MTO voucher users were compared with those of 1600 “controls” who were not provided with vouchers (Kling, Liebman, & Katz, 2007). A second strategy has facilitated poverty deconcentration through the demolition of public housing developments that are considered to be a structural cause of concentrated poverty (Bickford & Massey, 1991). In 1992, HUD initiated the HOPE VI program to fund the demolition of public housing, the relocation of public housing tenants, and the construction of mixed-income communities at the sites of demolished developments (Zhang & Weismann, 2006).

Such programs aim to foster escapes from urban “ghettos” through relocation, but do not consider or address the larger structural forces of racial exclusion that have given rise to these areas in the first place (Geronimus & Thompson, 2004). Additionally, those advocating deconcentration and the dispersal of “ghetto” communities, often have not considered the ways that spatial stigma may constrain opportunity and negatively affect the well-being of those who are compelled or forced to move. As Parker and Aggleton (2003) argue, stigmatization must be understood as a social process that works in the service of power to maintain social, political and economic inequality. In other words, for “ghetto” migrants, stigmatization may work to reinforce the systems of social stratification that have given rise to urban ghettos in the first place and may even contribute to the reemergence of such marginalized spaces in their new communities.

As a phenomenon that may contribute to the reproduction of social inequality, spatial stigma has important implications for the health of marginalized and disadvantaged populations such as the residents of high-poverty urban areas. According to Wakefield and McCullan (2005), landscapes can concretely influence the well-being of their residents when social divisions become spatialized and place limitations on the lives of those who inhabit them. As MacIntyre et al (2002) illustrate the social construction of places plays an important role in patterns of investment and disinvestment that shape opportunities for their residents. For those who leave stigmatized places, the discrediting marks of former residences may serve to justify subsequent exclusion from the social and economic resources that support health and well-being (Wakefield & McMullan, 2005). In this sense, spatial stigma may operate as what Link and Phelan (1995) define as a “fundamental cause” of illness; one that shapes “access to resources that help individuals avoid diseases and their consequences” (p.81).

Additionally, the behaviors that individuals employ in order to manage and resist stigmatization may have important health consequences. For example, Stead et al (2001) posit that collective smoking behaviors are one way that residents of marginalized Glasgow communities cope with the stigmatization of their neighborhoods. In another example, Popay et al (2003) find that one of the ways that residents of stigmatized places construct positive identities despite their surroundings is to withdraw from their communities and retreat to the private sphere. Wacquant (2008) observes a similar phenomenon in Chicago’s urban neighborhoods and posits that this form of symbolic self-protection reduces residents’ access to health-promoting social support. Finally, as indicated by a large body of literature, experiences of stigmatization may serve as a profound source of psychosocial stress (Link & Phelan, 2006). As stigmatized individuals encounter marginalization and unequal opportunities, social comparisons with those around them can lead to stress and frustration (Kawachi, 2000) which may negatively impact health directly, or through the coping mechanisms that individuals employ (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2006). As suggested by existing research on ethnic density and health (Pickett & Wilkinson 2008; Rabkin 1979), African Americans who relocate from high-poverty urban areas may experience health-demoting stressors as a result of their immersion in predominantly white communities. This may reinforce the systems of social exclusion that motivated their moves in the first place.

To examine processes of spatial stigma as they are experienced by those who relocate from high-poverty urban areas, we analyze in-depth interviews with 25 low-income and working-class African American men and women who have relocated from urban neighborhoods in Chicago to small cities and towns in eastern Iowa. These interviews were conducted as part of a broader study examining the out-migration of low-income minorities from Chicago in the context of gentrification, public housing demolition and concomitant shortages of affordable housing (Keene, Padilla and Geronimus 2010). Study participants describe moving to Iowa in search of safer neighborhoods, jobs, educational opportunities, subsidized or affordable housing and to “find something better” than what they had in Chicago. While Iowa affords many of these opportunities, participants also describe many challenges to making a new home there. In particular, participants describe encountering pervasive stigmatization that is associated not only with race and class, but also with their former residence in Chicago.

We analyze participants’ articulations of spatial stigma that relate to racialized and classed conceptions of Chicago’s urban neighborhoods. We also discuss the strategies that they employ in order to symbolically shed the burden of place that for many, seems to present a formidable barrier to getting by in Iowa. In the final section of this paper, we discuss the implications of spatial stigma for the health and well-being of Chicago-to-Iowa migrants.

Methods and Background

During the past decade, Chicago has undertaken dramatic urban revitalization efforts resulting in the demolition of virtually all of its high-rise public housing developments and contributing to gentrification in many neighborhoods that once housed low-income and working-class communities (Smith, 2006). Shortages of affordable housing, compounded by rising crime-rates and persistent job shortages have led some Chicago families to leave the city in search of safer and more affordable environments. Iowa City and the surrounding Johnson County, located 200 miles west of Chicago, have received small but significant numbers of low-income African Americans from Chicago. The Iowa City Housing Authority (ICHA), which serves all of Johnson County, reported in 2007 that 14% (184) of the families that it assists through vouchers and public housing were from Illinois. Additionally, the ICHA estimates that about one third of the approximately 1,500 families on its rental-assistance waiting list in 2007 were Chicago area families.

Participants describe several reasons for choosing Iowa as a destination. Many seek safe and affordable housing or are drawn by shorter waiting lists for housing subsidies that have become virtually unavailable in Chicago. Others cite Iowa’s reputation for excellent schools as an important opportunity for their children, and its affordable community colleges as a chance to advance their own educational goals. Additionally, many have come to Iowa in search of jobs that are plentiful in Johnson County’s home health-care industry, nursing homes, restaurants and hotels. This availability of work is contrasted sharply with Chicago where, as one participant states, “The jobs were just so limited”.

Despite their relatively small numbers, African Americans from Chicago are visible outsiders in Iowa’s predominantly white communities. Iowa City, where the majority of participants resided, is a town of approximately 60,000 and home to the University of Iowa. As a college town, it contains considerably more ethnic diversity than many Iowa communities and is home to a small number of African American professionals, students and faculty. However, the arrival of low-income African Americans from Chicago is a highly contentious issue and has given rise to a divisive local discourse that is often imbued with racialized and class-based stereotypes of urban areas (C. Wilson, 2007).

This study involved in-depth semi-structured interviews with Chicago-to-Iowa migrants, and two months of participant observation in sites deemed useful for understanding the experiences of migrant community members and their reception in Iowa. In the summer of 2008, we used recruitment fliers to contact former residents of Chicago who lived in Johnson County and who had either applied for rental assistance there or in Chicago. These fliers invited potential participants to “tell your story” and were posted in community centers, government offices, and other areas where former Chicagoans commonly gathered. In addition, some individuals were referred to us by other study participants, a form of snowball sampling. During the screening process, we used theoretical sampling procedures to maximize diversity in participant experiences along two theoretically relevant axes of diversity. First, because existing literature suggests that experiences with the local community and feelings about relocation are likely to change over time (Keels, Duncan, Deluca, Mendenhall, & Rosenbaum, 2005), we wanted to capture the experiences of both individuals who had recently arrived in Iowa and those who had lived there longer. As indicated in Table 1, approximately half of the participants resided in Iowa for more than 2 years. Second, we wanted to interview both individuals who had been displaced from demolished public housing developments and those who moved to Iowa for other reasons. As indicated in Table 1, absolute parity was not achieved in this respect despite adapting recruitment materials and intentionally seeking out those who had been directly affected by demolition. It is possible that this latter group was underrepresented among those who relocate to Iowa because residents of demolished projects are provided with replacement housing, while other low-income families may be pushed farther down on rental-assistance waiting lists (Ranney & Wright, 2000).

Table 1.

Theoretical Sampling Distribution

| More than 2 years in | Less Than 2 years in | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Directly Affected | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| Indirectly Affected | 8 | 8 | 16 |

| Total | 12 | 13 | 25 |

In all, 25 individuals participated in audio-taped semi-structured interviews lasting an average of 75 minutes. Participants also completed a short demographic survey, the results of which are presented in Table 2. The analytic process involved open-coding of interview transcripts, followed by focused-coding using a set of fixed codes and the data analysis software ATLAS-TI (Corbin & Strauss, 1998). All names and some small, potentially identifying details have been changed in order to protect participants’ anonymity.

Table 2.

Sample Demographic Characteristics, N=25

| Average Age | 33 |

| Average number of Months in Iowa | 26 |

| % Female | 84 |

| % African American | 100% |

| % With High School Diploma or GED | 72% |

| % With Some College | 44% |

| % With Housing Assistance in Iowa | 84% |

| % Ever resided in a CHA Project | 72% |

These interviews were supplemented with reviews of local media, key informant interviews with social-service providers and participant observation, conducted between May and August, 2008 at local community organizations, public events and neighborhood centers. Field-notes were taken and subsequently coded for major themes related to our interest in community manifestations of stigma, the meanings of place among locals and migrants and the public tensions generated by interactions between these two groups. Data from these field-notes provide important context for the interviews which are the main focus of our analysis.

Results

Stigma of Race, Class, and Place in Iowa

“I feel like because I am from Chicago, I’m already labeled”

-Lakia Johnson, age 34

In the predominantly white communities of eastern Iowa, black race is often a visible marker of outsider status. While not all African Americans in Iowa are from Chicago, blackness has come to be associated with Chicago’s high-poverty and predominantly minority neighborhoods, and also with defamed notions of urban poverty. As former residents of these discredited spaces, many Chicagoans are, as Lakia says above, “already labeled”.

For example, in Iowa, ‘Chicago’ is often associated with drugs, violence and crime that are perceived to taint small town life. Our review of online newspapers found that reports of crime often elicit numerous racially charged comments about an influx of Chicago residents, even when the origin or race of the perpetrator is not mentioned. For example, in response to an article about Chicago-to-Iowa migrants, one blogger writes,

I understand that people want to do better for their families. That is very nice. In the meantime, they’re bringing the ghetto with them and letting loose. We have crimes that we didn’t have before. I see in the paper, crime after crime: “a black man in his 20s”

One participant, 54 year-old Diane Field, complains that Chicago is blamed for everything that goes wrong in Iowa and is frequently “scandalized” in public discourse. She says,

It’s just Chicago, Chicago, Chicago…Everywhere you go…It makes me mad when they say Chicago, Chicago, when this is happening all over the United States…There were drugs in Iowa long before anyone from Chicago ever came here.

In Iowa’s public discourse, Chicago is also often associated with stigmatizing conceptions of poverty and welfare dependency. Of particular concern among some Iowans, is the idea that an influx of low-income Chicagoans will overburden social-welfare systems. As one letter to City Council states, “We are turning into a Mecca for out-of-state, high maintenance welfare recipients. These often dysfunctional families are causing serious problems for our schools and police” (Sanders, 2004).

According to Martin (2008), concerns about the well-being of children often provide a more socially acceptable way to object to the class and race differences of new neighbors. Such objections were evident at a meeting in one Johnson County school where parents expressed concerns that the needs of students arriving from sub-par urban schools would exhaust limited resources and negatively impact their own children’s educations. Parents also expressed concern that Chicago families did not “value education” in the same way they did, and were surprised to hear that Iowa’s “excellent school system” was discussed at length by study participants as a primary reason for moving to and staying in Iowa.

Several participants describe feeling resentful and angry about the way they were perceived by many Iowans. For example, 32 year-old Carol Williams says,

I mean the killer part about Iowa City, cause you can’t point your finger at every black person who came and say, well, oh here goes another black person, they must be selling drugs or they came down here to get this section 8 or whatever. Most people is not like that.

Several participants also describe how negative stereotypes of ‘Chicago’ constrain their opportunities in Iowa. Prevalent in participants narratives are experiences of race related discrimination, in particular from the local police, who they frequently call out for rampant “racial profiling”, and from Child Protective Services, who as 24 year-old Christine Frazier says, “Don’t respect the rights of young black mothers”. Forty-two year-old Michelle Clark attributes the challenges that she has faced in her search for better paying work to race-based discrimination. She says, “To me, they think that black people don’t have no professional skills”. For Michelle, the ability to meet basic needs through access to work was strongly constrained by race-based assumptions about her qualifications and professional abilities.

Some participants also describe instances of discrimination that they feel are directly related to their former residence in Chicago. For example, 32 year-old Anita Mann says,

Well, it’s like when you say you’re from Chicago around certain people and I ain’t just going to say the police, I’m saying other people like, if you’re trying to get housing or some kind of low income for your family, it’s like they discriminate on you because you say where you’re from, Chicago…. To me it seems they make it harder for people who come from Chicago, than if I came from Kentucky or somewhere.

Anita goes on to describe multiple instances where African Americans from other places were treated better than former Chicagoans. For example, she says that one landlord refused to rent to her friend because she was from Chicago, but then leased the same unit to another African American woman from Indiana.

Experiences with housing discrimination and residential segregation are common in participants’ narratives. As Christine says, “It sort of looks like they section us off. They try to put us in certain places to do certain things or be with certain people”. Lakia describes being disappointed to find herself living near other former residents of Chicago. She says,

I feel like the only day I was really happy for me being over there in that apartment was my first day moving in there. Because I was like ‘Wow, I’m in a new state, new people. God man, thank you! Everything is going to be so different’. Then I found out all of them people’s from Chicago [were there]. I said, oh, my god, you’re going to put me back in [the projects].

Indeed, in Iowa City, many former Chicagoans live in a few housing complexes on the southeast side of town. In public discourse, the southeast side has come to be associated with many stereotypes of urban areas. One Iowa City social worker notes that the area has become particularly associated with crime, despite the fact that similar crime rates exist in the predominantly white neighborhoods that surround the University of Iowa. The stigmatization of this area seems to have resulted in a withdrawal of some services and resources. For example, a newspaper article documents the recent decision of one local pizza place to cease delivery to the southeast side in order to ‘protect the safety of their deliverers’ (Herniston, 2009).

Lakia, who says that she is already labeled because she is from Chicago, explains that she sometimes wishes she could tell people that she is from “Indiana or somewhere else” in order to avoid this label. Indeed, as stigmatized outsiders in what 34 year-old Danielle Martin describes as “someone else’s city” participants face many challenges to their day to day survival in Iowa. And in some senses, this survival may be contingent on their ability to distance themselves from the stigma associated with their former residence. Below, we describe some of the strategies that participants employ in order to do this.

“Defensive Othering” and the Negotiation of Spatial Stigma

I know it’s some peoples up here I mean, like taking Iowa City advantage, but me up here, I am not doing that. I am up here trying to do something for me and my kids. I am not like all the other peoples up here, you know what I am saying. My outlook is different from everybody else.

– Carol Williams, age 32

Throughout her narrative and in the statement above Carol repeatedly emphasizes the differences between herself and other former Chicago residents, a form of “identity talk” (Snow & Anderson, 1987) that she seems to employ in order to deny membership in this discredited category. Other participants make similar distinctions between themselves and other Chicagoans. In emphasizing their own uniqueness, participants often seem to tacitly accept dominant stigma narratives about Chicago, using them as a point of contrast for their own situation and, as Wacquant (1996) says, “Thrusting the stigma onto a faceless, diabolized Other” (p 126). Ezzell (2009) refers to this strategy of saying, “there are indeed others to whom this applies but it does not apply to me” as “defensive othering” (p. 112).

One way that participants engage in “defensive othering” is by contrasting their own desire to leave behind discursively condemned Chicago neighborhoods and their residents, with those who “bring Chicago to Iowa” by getting involved with drugs, gangs, or more broadly engaging in behaviors that are stereotypically associated with urban poverty. Participants frequently discuss their desire for “change”, “something better”, “a fresh start” or to “step out of the box”. Thirty-four year-old Karen Bates explains that change is really the only valid reason to come to Iowa. She says, “If you’re not willing to change, or change the atmosphere, change the pace, and change everything, if you don’t have a motive to come down here to do it, it’s no use in coming.”

In describing this quest for something different, participants seem to express a desire, not only to change aspects of their own lives, but to escape the presumed pathological environment of Chicago neighborhoods. In particular, participants emphasize a desire to remove their children from the negative influences of these neighborhoods and their residents. For example, 32 year-old Tara Smith says,

So, that was my decision of coming out here, because I wanted more for my kids than that lifestyle. I didn’t want them to grow up and you know, think it’s alright to shoot somebody, or ….it’s alright to just disrespect anybody. So, they learned from the experience of me moving them out from Chicago to Iowa, that it’s not good, that wasn’t a good environment that they were living in.

Participants often contrast their own motivation for change with those of an anonymous other who does not leave ‘Chicago’ behind. As 33 year-old Marion Simms says, “Some black men and some black women that come from Chicago down here, they getting twisted and act like they acted when they was in Chicago”. Several participants complain that people who, as 34 year-old Tanya Neeld says, “Bring that Chicago attitude down here, as far as forming gangs and gang banging and drug-selling and things like that” present challenges for those who want to “do the right thing”. Fifty-four year-old Ernestine Coles says, “The wannabe gang bangers or whatever they’re calling themselves, want to destroy what you’ve got. And they make it hard on us. People look at us the wrong way. It’s not our fault”. Likewise, Christine attributes some of the problems that she has encountered with Child Protective Services in Iowa to the fact that she is lumped together will other Chicagoans and their presumed negative behaviors. She says,

“They done run into so many bad black people, they don’t trust all of us. They look at us as a whole”.

In a context where ‘Chicago’ is often associated with stigmatized notions of poverty and dependency on government aid, participants also use “defensive othering” to distance themselves from these conceptions. For example, a few contrast their own desire for change with others, who they perceive as coming to Iowa only to receive housing vouchers that can be transported back to Chicago. (Housing vouchers must be used in the county where they are issued for 18 months, but then can be “ported” to another location). This practice of “playing the system” and “taking advantage of Iowa” is denounced in public discourse and also in some participant narratives. For example Danielle says,

There’s so many people who’ve came here to get their Section 8 [vouchers] and then they leave with it …. You know, so if you gonna come strictly for a little while and just do this and get this together and then just leave, you’re not really appreciating what the city has to offer.

Lakia explains that many women can’t afford housing in Chicago, and come to Iowa for housing assistance when they simply have no other options. However, at another point in the interview, she echoes public discourse and denigrates those who do so stating,

So for me, my thing is, I wish there was some way to close the [housing] waiting list down for 4, 5, 6 years. They really need to do it because people is just taking advantage of it and they’re really not doing what they are supposed to be doing down here, which is coming down here and doing the right thing.

While all participants had applied for housing assistance in either Iowa or Chicago, they come from a variety of socioeconomic backgrounds. In the process of distinguishing themselves from other Chicagoans, some emphasize these class distinctions. For example, Michelle, who grew up in a home owned by her parents, says,

I think they stereotype everybody here, like they never had anything or used to anything. That’s why I’m so defensive when it comes to them, because I never was poor. I don’t even consider myself poor ‘cause I got housing [assistance].

Michelle also emphasizes that she has never lived in Chicago’s infamous public housing projects. In describing one particular Iowa apartment complex she says,

“That looks like project housing. I don’t want to live in nothing like that. I wasn’t raised like that. I was raised on the South side, in a house on the South side of Chicago. I don’t know anything about no projects”.

Ernestine, who moved out of one Chicago public housing development a few years prior to its demolition, describes the stigma associated with public housing residence. She says, “You tell people you came from the projects and it makes them look at you another way”. In Iowa, where a common perspective is that former residents of demolished projects have descended upon the state, placing a burden on its social-welfare system, the stigma associated with public housing may be particularly pronounced. In this context, it seems that some former public-housing residents attempt to rhetorically distance themselves from their former homes. For example, Anita, who grew up in Robert Taylor Homes, explains that she was not of the projects, because she was raised by a strict grandmother who sheltered her from the surrounding environment. She says, “The streets didn’t raise me. Big Mama raised me. There’s a difference.” Likewise, when asked how the demolition of his public housing building affected him, 33 year-old Michael Robertson says, “Well, I adapted, because I am used to living in homes and houses, you know, I mean, I wasn’t in it like they was in it. I was just there observing. I wasn’t doing what they was doing”

While above Michael states that he was in but not of stigmatized public housing developments, feigning emotional detachment, during another part of the interview, he engages in a lengthy discussion of how profoundly the loss of the place he called home affected him. He says,

I watched a lot of people grow up and they been there for years. And then for you to see the building tore down, they being separated. So I look at that as a tragedy in your own heart, in your own mind it’s a tragedy, because you probably don’t ever see these people again.

As participants seek to distance themselves from a stigmatized “other”, a few even deny the experience of stigma itself. For example, 36 year-old Amber Price, who has lived in Iowa for five years, explains that she has been successfully able to distance herself from the stigma associated with Chicago. She says, “My thing is it’s up to that individual to let them know, ‘I’m not like all Chicagoans that you’ve come across’. And I am determined to do that.”

Stigma Avoidance and Social Isolation

“I didn’t let myself get boxed in with other people. You can’t say, because I’m hanging with this person, then this is who I am. I never surround myself with those people”.

- Amber Price, age 36

One of the ways that Amber reinforces the idea that she is not like other Chicagoans is by carefully selecting who she associates with and by generally avoiding contacts with other Chicagoans. As she says in the quote above, “I didn’t let myself get boxed in”. Lakia explains that when she first arrived in Iowa this strategy of selective association (Goffman 1963; Snow and Anderson 1987; Wacquant 2007) was explicitly taught to her. She says, “My girl Marie told me when I come down here, make sure to stay to myself. Don’t talk to nobody. She said a lot of black people down here are basically trouble”. Michelle also describes keeping to herself as an explicit strategy employed to negotiate her marginalized status in Iowa. She says,

They act like they really don’t want us here. They try to make like we keep up so much trouble. I don’t know what the rest of these people are doing. That’s why I stay to myself. They could be gangbanging and selling drugs or whatever, I don’t know. I don’t care. I’m just trying to live

As discussed above, many participants express a desire to escape, not only marginalized Chicago neighborhoods, but also the residents of these neighborhoods who in the context of residential segregation, often become their new neighbors in Iowa. As 36 year-old Marlene Edwards says,

I don’t think about my neighborhood at all. I just run from it. Because the area that I live in, a lot of minorities that left the city, that I also ran from, they came here with bad habits and not being very respectful. Just not brought up right inside the home, I assume.

Tanya echoes this sentiment stating, “I really don’t do much socializing with people in the building. I’ve seen how ignorant they act, you know amongst each other…So I try not to involve myself in that”.

Such strategies of stigma avoidance, compounded by separation from Chicago-based social networks, seem to contribute to experiences of social isolation among Chicago-to-Iowa migrants. As 29 year-old Vanessa Thompson explains,

Being here, you have to have more patience, because you don’t have your mom, you don’t have your [childrens’] fathers, and you don’t got your grandma and your auntie and your cousins. You’re here by yourself.

For many participants, this isolation poses both emotional and material challenges in Iowa. Some describe loneliness and depression. Others describe the challenges of maintaining a job without childcare support from friends and family. A few describe having no one to turn to in trying moments such as a child’s illness or a household fire.

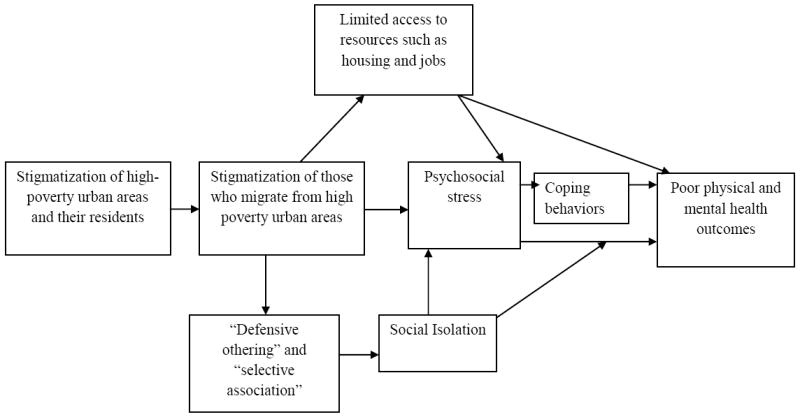

Spatial Stigma and Health

Participants in this study, like other African American residents of high-poverty urban areas (Geronimus, 2000), seem to experience a disproportionately high burden of poor health. Depression, diabetes, high blood-pressure, headaches and child-birth complications were frequently reported among participants, perhaps the result of cumulative exposure to social and economic marginalization across the life-course. While a few participants describe the health benefits of Iowa’s safer communities and more plentiful economic opportunities, others attribute headaches, weight-gain, emotional distress and insomnia to the stressors they have experienced there. Below we discuss some specific pathways by which ‘spatial stigma’ as theorized in the existing literature and illustrated by participants’ experiences, may contribute to such stress and health vulnerability among Chicago-to-Iowa movers (see Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Spatial Stigma among Low-Income, African American Chicago-to-Iowa Movers

In the first pathway, stigma affects access to social and economic resources that contribute to health and illness, both directly, and also indirectly through stress. As Link and Phelan (2006) state, “The extent to which a stigmatized person is denied good things in life and suffers more of the bad things has been posited as a source of chronic stress, which has consequent negative effects on mental and physical health.” (p528). As discussed above, several participants describe barriers to receiving services, findings jobs or accessing resources which they attribute to the stigmatization. Additionally, several participants describe experiences of housing discrimination and resegregation into Iowa City’s most socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods, where health-promoting resources are likely to be less plentiful and health hazards more prevalent (Williams and Collins 2001).

A second pathway describes how stigmatization leads directly to psychosocial stress. Participants’ quests for opportunity in Iowa have brought them to a whiter community where they confront head-on the systems of racial exclusion that have produced the unequal geographic distribution opportunity they seek to escape. Research has shown that in the context of such inequality ‘invidious social comparisons’ can be a source of profound psychosocial stress which can directly impact health or operate indirectly through unhealthy coping mechanisms (Kawachi, 2000; Wilkinson & Pickett, 2006). In this study we found evidence of such social comparisons in participants’ articulations of frustration at the unjust treatment that they received in Iowa.

Additional pathways operate through the strategies that participants employ in order to manage and resist the stigmatization that they experience. In particular, strategies of “defensive othering” and “selective association” described above contribute to social isolation and limit participants’ access to social support. The important contribution of social integration to health is well-established (Berkman, Glass, Brissette, & Seeman, 2000) and social support resources may be particularly important for socially marginalized and socioeconomically disadvantaged populations such as African American residents of high-poverty neighborhoods (Geronimus, 2000). For example, ethnographic literature indicates that the pooling of risks and resources across social networks is a critical survival strategy employed to mitigate the health costs associated with limited economic opportunity (Edin & Lein, 1997; Mullings & Wali, 1999; Stack, 1974). In addition, social networks may provide important psychosocial resources that help buffer against the health consequences of stigma related stress in Iowa. On an ecologic or community level, the strategies of social distancing reported by our participants are likely to inhibit the development of social networks and social capital, which have been shown to facilitate collective action and promote health and well-being (Kawachi & Berkman, 2000).

Discussion

A handful of recent studies have explored the stigmatization of high-poverty urban areas and the consequences of such place-based stigma for health and well-being (Popay et al., 2003; Wacquant, 2007, 2008). We extend this work by examining how ‘spatial stigma’ is embodied and transported to new destinations. Participants in this study describe how as African Americans from Chicago, they are “already labeled” with the many negative stereotypes associated with racialized conceptions of urban poverty. This stigmatization appears to constrain their opportunities in Iowa and impose stressors that are likely to have significant health consequences. Studies of other stigmatized populations such as the homeless (Snow & Anderson, 1987), former prisoners (Harding, 2003) and the disabled (Goffman, 1963) have described strategies that stigmatized individuals employ to distance themselves from stigmatized identities and their consequences. We observed similar phenomena among Chicago-to-Iowa movers who employed “defensive othering” and selective association in order to avoid the label of “just another one from Chicago”. Our analysis suggests that these strategies, while potentially effective in mitigating stigma, may contribute to social isolation and further erode health.

One limitation of our findings, is that they are based largely on participants’ self-reports of stigmatizing experiences and their social consequences. These data do not allow us to generalize experiences of place-based discrimination to a larger population, nor can we with any certainty claim that Chicago migrants are treated differently than other Iowans. Nevertheless, among this sample of Chicago-to-Iowa migrants, we have been able to deeply explore individual perceptions of stigmatization, discrimination and coping, a perspective that is absent in much of the existing and largely quantitative literature on relocation. We believe that this perspective is critically important to understanding the health costs of relocation and should be examined systematically in subsequent research.

Our findings offer two critical insights for future scientific inquiry. First, the concept of spatial stigma may be useful in understanding the health costs associated with a wide range of migration experiences. With few exceptions (eg Wang, Li, Stanton, & Fang, 2010), the large existing literature on migration has not directly examined this issue, despite extensive global research on migrant health. Second, participants’ experiences of stigmatization may provide insight into some potential limitations of recent programs that have advocated mobility as a strategy for poverty alleviation. While relocation from high-poverty neighborhoods is widely assumed to be beneficial, existing evidence has not always supported this assumption. For example, studies of Moving to Opportunity suggest that relocation to lower poverty neighborhoods is associated with a mix of positive and negative outcomes (Jackson, Langille, Lyons, Hughes, Martin, & Winstanley, 2009; Kling et al., 2007). Studies of HOPE VI suggest that relocation from demolished public housing developments may have had serious health consequences (Manjarrez, Popkin, & Guernsey, 2007). Experiences of stigmatization, such as those described in this study, may limit movers’ ability to derive health benefits from relocation.

Finally, the experiences of participants in this study suggest a need to consider the discursive processes that may contribute to the production of spatial stigma. For example, poverty deconcentration initiatives may reinforce defamed notions of urban communities and contribute to the production of spatial stigma by suggesting that these areas must be escaped and erased from the landscape, rather than invested in and protected. The discourse surrounding poverty deconcentration often obscures the fact that urban “ghettos” did not arise organically, but resulted from specific policies and practices of exclusion and investment (Wacquant, 1997). Without consideration of the structural context that produced areas of concentrated poverty, the “ghetto” is often constructed as the product of the presumed pathological behaviors and practices of its residents, thus reinforcing popular notions of places that are not only materially disadvantaged, but also morally and culturally depraved. Furthermore, the discourse surrounding poverty deconcentration often fails to consider the many social resources that support health and well-being in high-poverty urban communities (Greenbaum, 2002). This negative portrayal may contribute to the construction of “spoiled identities” (Goffman 1963) among persons who are tainted by the nature of their residence in stigmatized places.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Danya E Keene, University of Michigan Population Studies Center, 426 Thompson St., Ann Arbor, MI 48106, danyak@umich.edu.

Mark B. Padilla, Department of Health Behavior and Health Education, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, 109 Observatory St., Room #3830, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, padillam@umich.edu.

References

- Acevedo-Garcia D, Lochner KA, Osypuk TL, Subramanian SV. Future directions in residential segregation and health research: a multilevel approach. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):215–221. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;51(6):843–857. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickford A, Massey D. Segregation in the second ghetto: racial and ethnic segregation in American public housing, 1977. Social Forces. 1991;69(4):1011–1036. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin A, Strauss J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing a Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, Lein L. Making Ends Meet: How Single Mothers Survive Welfare and Low-Wage Work. New York: Russell Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen IG, Turner MA. Does neighborhood matter? Assessing recent evidence. Housing Policy Debate. 1997;8(4):833–866. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle B. Putting people into place. Demography. 2007;44(4):687–703. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzell MB. “Barbie dolls” on the pitch: identity work, defensive othering, and inequality in women’s rugby. Social Problems. 2009;56(1):111–131. [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT. To mitigate, resist, or undo: addressing structural influences on the health of urban populations. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(6):867. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.6.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT, Thompson JP. To denigrate, ignore or disrupt: racial inequality in health and the impact of a policy induced breakdown of African American communities. Du Bois Review. 2004;1(2):247–279. [Google Scholar]

- Goetz E. The Politics of Poverty Deconcentration and Housing Demolition. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2001;22(2):157–173. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of a Spoiled Identity. New York: Simon and Shuster; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Goode J, Maskovsky J. Introduction. In: Goode J, Maskovsky J, editors. The New Poverty Studies: The Ethnography of Power, Politics, and Impoverished People in the United States. New York: New York University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon IR. Urban Unemployment. In: Herbert DT, Smith DM, editors. Social Problems and the City: New Perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1991. pp. 232–246. [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum S. Social capital and deconcentration: theoretical and policy paradoxes of the HOPE VI program. North American Dialogue. 2002;5(1):9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Harding DJ. Jean Valjeans dilemma: the management of ex-convict identity in the search for employment. Deviant Behavior. 2003;24:571–595. [Google Scholar]

- Herniston L. Pizza Pit slices S E delivery. Iowa City Press Citizen; Iowa City: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson L, Langille L, Lyons R, Hughes J, Martin D, Winstanley V. Does moving from a high-poverty to lower-poverty neighborhood improve mental health? A realist review of [‘]Moving to Opportunity’. Health & Place. 2009;15(4):961–970. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I. Income Inequality and Health. In: B L, Kawachi I, editors. Social Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 76–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Berkman L. Social Cohesion, Social Capital and Health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, editors. Social Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 174–189. [Google Scholar]

- Keels M, Duncan GJ, Deluca S, Mendenhall R, Rosenbaum J. Fifteen Years Later: Can Residential Mobility Programs Provide a Long-Term Escape from Neighborhood Segregation, Crime, and Poverty? Demography. 2005;42(1):51–73. doi: 10.1353/dem.2005.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene D, Padilla M, Geronimus AT. Leaving Chicago for Iowa’s “Fields of Opportunity”: Community Dispossession, Rootlessness and the Quest for Somewhere to “Be Ok”. Human Organization. 2010;69(3):277–284. doi: 10.17730/humo.69.3.gr851617m015064m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelaher M, Warr D, Feldman P, Tacticos T. Living in Birdsville: exploring the impact of neighborhood stigma on health. Health and Place. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.11.010. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kling JR, Liebman JB, Katz LF. Experimental analysis of neighborhood effects. Econometrica. 2007;75(1):83–119. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;35:80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Stigma and its public health implications. The Lancet. 2006;367(9509):528–529. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macintyre S, Ellaway A, Cummins S. Place effects on health: how can we conceptualise, operationalise and measure them? Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55(1):125–139. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manjarrez C, Popkin S, Guernsey E. Poor health: adding insult to injury for HOPE VI families. The Urban Institute Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Martin L. Boredom, drugs, and schools: protecting children in gentrifying communities. City & community. 2008;7(4):331–346. [Google Scholar]

- Mullings L, Wali A. Stress and Resilience: The Social Context of Reproduction in Central Harlem. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Musterd S, Andersson R. Housing mix, social mix and social opportunity. Urban Affairs Review. 2005;40(6):761–790. [Google Scholar]

- Neckerman KM, Kirschenman J. Hiring Strategies, Racial Bias, and Inner-City Workers. Social Problems. 1991;38(4):433–447. [Google Scholar]

- Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57(1):13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickett K, Wilkinson R. People like us: ethnic group density effects on health. Ethnicity and Health. 2008;13(4):321–334. doi: 10.1080/13557850701882928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popay J, Thomas C, Williams G, Bennett S, Gatrell A, Bostock L. A proper place to live: health inequalities, agency and the normative dimensions of space. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57:55–69. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00299-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabkin JG. Ethnic density and psychiatric hospitalization: hazards of minority status. American Journal of Psychiatry. 136:1562–1566. doi: 10.1176/ajp.136.12.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranney D, Wright P. Race, class and the abuse of state power: the case of public housing in Chicago. SAGE Race Relations Abstracts. 2000;25(2):3. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson R, Morenoff J, Gannon-Rowley T. Assessing “neighborhood effects”: social processes and new directions in research. Annual Review of Sociology. 2002;28:443–478. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders D. Don Sanders’ Observations- Letter to City Council. Iowa City: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. The Chicago Housing Authority’s Plan for Transformation. In: Bennett L, Smith J, Wright P, editors. Where are Poor People to Live? Transforming Public Housing Communities. Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe; 2006. pp. 93–125. [Google Scholar]

- Snow DA, Anderson L. Identity work among the homeless - the verbal construction and avowal of personal identities. American Journal of Sociology. 1987;92(6):1336–1371. [Google Scholar]

- Stack C. All Our Kin. New York: Basic Books; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Stead M, MacAskill S, MacKintosh A-M, Reece J, Eadie D. “It’s as if you’re locked in”: qualitative explanations for area effects on smoking in disadvantaged communities. Health & Place. 2001;7(4):333–343. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(01)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant L. The rise of advanced marginality: notes on its nature and implications. Acta Sociologica. 1996;39:121–139. [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant L. Three pernicious premises in the study of the American Ghetto. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 1997;21(2):341–353. [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant L. Territorial stigmatization in the age of advanced marginality. Thesis Eleven. 2007;91:66–77. [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant L. Urban Outcasts. Cambridge: Polity Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield S, McMullan C. Healing in places of decline: (re)imagining everyday landscapes in Hamilton, Ontario. Health & Place. 2005;11(4):299–312. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Li X, Stanton B, Fang X. The influence of social stigma and discriminatory experience on psychological distress and quality of life among rural-to-urban migrants in China. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71(1):84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson RG, Pickett KE. Income inequality and population health: A review and explanation of the evidence. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62(7):1768–1784. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Collins C. Racial Residential Segregation: A Fundamental Cause of Racial Disparities in Health. Public Health Reports. 2001;116:404–416. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C. New Iowans: An Exploration of the Implications of Reverse Migration- Cities to Small Towns- for Our Understanding of Whiteness and Otherness in America’s Heartland 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. The Truly Disadvantaged. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Weismann G. Public Housing’s Cinderella: Policy Dynamics of HOPE VI in the Mid-1990s. In: Bennettt L, Smith J, Wright P, editors. Where are Poor People to Live? Transforming Public Housing Communities. Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe; 2006. pp. 41–67. [Google Scholar]