Abstract

Background

Hereditary Spastic Paraplegias (HSP) are characterized by progressive spasticity and weakness of the lower limbs. At least 45 loci have been identified in families with autosomal dominant (AD), autosomal recessive (AR), or X-linked hereditary patterns. Mutations in the SPAST (SPG4) and ATL1 (SPG3A) genes would account for about 50% of the ADHSP cases.

Methods

We defined the SPAST and ATL1 mutational spectrum in a total of 370 unrelated HSP index cases from Spain (83% with a pure phenotype).

Results

We found 50 SPAST mutations (including two large deletions) in 54 patients and 7 ATL1 mutations in 11 patients. A total of 33 of the SPAST and 3 of the ATL1 were new mutations. A total of 141 (31%) were familial cases, and we found a higher frequency of mutation carriers among these compared to apparently sporadic cases (38% vs. 5%). Five of the SPAST mutations were predicted to affect the pre-mRNA splicing, and in 4 of them we demonstrated this effect at the cDNA level. In addition to large deletions, splicing, frameshifting, and missense mutations, we also found a nucleotide change in the stop codon that would result in a larger ORF.

Conclusions

In a large cohort of Spanish patients with spastic paraplegia, SPAST and ATL1 mutations were found in 15% of the cases. These mutations were more frequent in familial cases (compared to sporadic), and were associated with heterogeneous clinical manifestations.

Background

The hereditary spastic paraplegias (HSP) are characterized by progressive spasticity and weakness of the lower limbs due to axonal degeneration in the pyramidal tract. The disease is classified as "pure" when spasticity is the only clinical finding, and as "complicated" when other clinical features (dementia, cerebellar ataxia, epilepsy, peripheral neuropathy) are also present [1]. HSP is frequently familial and at least 45 loci have been identified in families with autosomal dominant (AD), autosomal recessive (AR), or X-linked inheritance [2-4]. This genetic heterogeneity partly explains the differences in disease severity, age at onset, rate of progression, and degree of disability between families. However, intrafamilial heterogeneity is also frequent.

SPG4 (OMIM#604277) is the most common form of HSP, accounting for approximately 40% of the familial and 6-15% of the sporadic cases. The SPAST/SPG4 gene encodes spastin, a member of the AAA (ATPase associated with various cellular activities) family of proteins, implicated in the remodeling of protein complexes upon ATP hydrolysis and the coordination of axonal microtubule interactions with the tubular endoplasmic reticulum network [5,6]. To date, >240 SPAST mutations have been reported (http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php; date of consultation August 2, 2010), mainly in patients with pure HSP [7-12]. Most of the SPAST mutations are single-nucleotide changes or small deletions/insertions, but large deletions and duplications have also been reported [13-16]. This suggested that both, haploinsufficiency and "toxic" gain of function could explain the pathogenic mechanism of SPAST mutations [5,17-19].

SPG3A (OMIM#606439) is the second most frequent form of ADHSP. The ATL1/SPG3A gene encodes atlastin, a protein localized in the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi and implicated in vesicle trafficking and neurite outgrowth [20,21]. To date, >25 ATL1 mutations have been reported (http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php; date of consultation August 2, 2010), mainly missense changes that supported a gain of function pathogenic mechanism. ATL1 mutations accounted for approximately 10% of the ADHSP families, and have been mainly found in pure HSP [22,23]. ATL1 mutations are also frequent in early onset (childhood or adolescence) cases [24-26].

This is the first report of the mutational spectrum of the SPAST and ATL1 genes in a large cohort of unrelated HSP patients from Spain. Few studies on cohorts >200 patients have been published, and the parallel screening of both genes was rarely reported.

Methods

Patients

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Hospital Universitario Central Asturias (HUCA), and all the participants (patients and controls) signed an informed consent. A total of 370 non-related patients (index cases) were recruited through the Neurology Departments of several Hospitals from Spain. HSP was diagnosed by qualified neurologists on the basis of Harding's criteria. Based on the clinical, radiological, and biochemical findings, cases with diseases that mimicked spastic paraplegia were excluded [27]. A total of 141 patients (38%) had a family history of HSP with a dominant inheritance pattern, and were thus classified as ADHSP cases. The absence of family history of the disease was established in 229 patients (62%) after interview on their first and second degree relatives. These cases were classified as "apparently" sporadic or with an uncertain inheritance pattern. In 177 of these the two parents were alive and did not have symptoms consistent with HSP, while in 52 the inheritance pattern could not be established because no clinical data were available from relatives.

SPAST and ATL1 sequencing

DNA was obtained from blood leukocytes and the 17 coding exons of SPAST (plus at least 50 bp of the flanking intronic sequences) were polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified (Additional file 1, Table S1). PCR fragments were purified and the two strands were sequenced using Big Dye chemistry in an ABI3130 system (Applied Biosystems, Ca, USA). These sequences were compared with the SPAST reference sequence (ENSG00000021574 for the genomic; ENST00000315285 for the transcript; http://www.ensembl.org). In patients who were negative for SPAST mutations and had ADHSP (n = 88) or patients without a family history of HSP and onset age ≤20 years (n = 99), we amplified and sequenced the 13 coding exons of ATL1 (reference sequences ENSG00000198513 for the genomic, and ENST00000358385 for the transcript; http://www.ensembl.org). All the DNA sequence variants were named following the guidelines of the Human Genome Variation Society (http://www.hgvs.org/mutnomen).

Controls screening

All the new putative mutations (not previously reported as SPAST or ATL1 mutations or polymorphisms) were screened in 400 controls. These were healthy individuals aged 21-65 years recruited through the Blood Bank of HUCA. The new nucleotide changes were genotyped through PCR-RFLP, single strand conformation analysis (SSCA), or denaturing high performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC), as reported [28]. Each PCR fragment containing a putative mutation gave a characteristic RFLP, SSCA or DHPLC pattern, and we could thus determine its presence/absence in the controls. When a new nucleotide change was not found among the 400 controls we determined, when it was possible, the carrier status of all the available affected relatives to confirm the segregation of the mutation with the disease.

MLPA analysis

The multiplex ligation dependent probe amplification (MLPA) assay with the Salsa Kit P165 HPA (MRC Holland, Amsterdam) was used to determine the existence of genome copy number aberrations in the SPAST and ATL1 genes in ADHSP patients who were negative for sequencing mutations [13]. To investigate the consequences of large SPAST deletions at the transcript level, we isolated the mRNA from leukocytes in 10 ml of blood (Trizol reagent, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and synthesised the cDNA (Quantitec Reverse Transcripcion kit, Quiagen, Hilden, Germany). The cDNA was amplified with primers that matched exons flanking the deletion (conditions available upon request), and the PCR products were purified and sequenced.

Analysis of SPAST transcripts

To determine the effect of some SPAST mutations on mRNA transcripts, the cDNA synthesised from leukocytes was amplified with primers that matched the exons flanking the mutation (additional file 1, Table S2), and the PCR fragments were purified from agarose gels and sequenced.

Statistical analysis

The analysis of variance (SPSS 17.0 software) was used to compare the mean onset age and disease duration between patients with mutations in SPAST and ATL1 and patients without mutations.

Results

Patients characteristics

We studied a total of 370 unrelated HSP index cases, with a mean onset age of 28 (± 21) years (range 1-77 years), and a mean disease duration of 17 (± 15) years. A total of 321 patients (87%) had a pure HSP, while 49 (13%) were complicated cases with peripheral neuropathy (the most frequent finding), cerebellar or cerebral atrophy, mental retardation, nystagmus, or dysarthia.

A total of 44 of the 141 patients (31%) with ADHSP had a SPAST mutation, and 10 mutations were found among the 229 (5%) cases apparently sporadic or with an uncertain inheritance pattern. However, in three of these patients the mutation (p.Leu426Val, p.Lys503insArg, and p.Met390Val) was de novo because none of the two parents was mutation carrier (the paternity was confirmed). We found 10 ATL1 mutation carriers among 88 ADHSP cases (11%), and the only apparently sporadic proband had a de novo mutation (p.Gln154Glu) (Additional file 2, Figure S1).

SPAST mutations

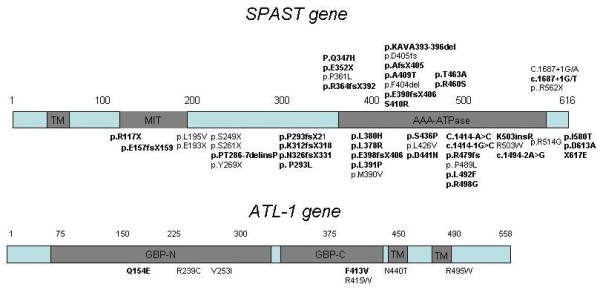

We found 48 SPAST mutations in 52 patients (Table 1). These were missense changes in amino acids conserved between species (n = 22), nonsense mutations (n = 7), small frameshifting insertions/deletions (n = 13), nucleotide changes in the intronic splicing consensus sequence (n = 5), and a sense mutation in the stop codon (Figure 1). A total of 15 mutations had been previously reported, while 33 (69%) were novel.

Table 1.

Mutations identied in the SPAST gene in the Spanish HSP cohort.

| Case | Onset age (Years) | Phenotype* | GENE | EXÓN | Mutation | Protein change | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 193 | 60 | Pure-UHSP | SPAST | 1 | c.349C->T | p.Arg117X | This study |

| 69 | 45 | Pure-SHSP | SPAST | 2 | c.469delG | p.Glu157f sX159 | This study |

| 81 | 35 | Pure-SHSP | SPAST | 3 | c.577C>T | p.Gln193X | [7] |

| 138 | 2 | Complicated-ADHSP | SPAST | 3 | c.583C->G | p.Leu195Val | [10] |

| 166 | 43 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 5 | C.782C>G | p.Ser261X | [7] |

| 197 | 53 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 5 | c.857-859delCTA | p.Pro286-Thr287delinsP | This study |

| 257 | 23 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 5 | c.806c->G | Tyr269X | [7] |

| 300 | 8 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 5 | c.746C>G | p.Ser249X | [8] |

| 174 | 1 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 6 | c.879delG | p. Pro293fsX314 | This study |

| 205 | 20 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 6 | .936-37insA | pLys.312fsX318 | This study |

| 206 | 30 | Pure- UHSP | SPAST | 6 | c.977-978insA | p.Asn326fsX331 | This study |

| 335 | 32 | Pure- SHSP | SPAST | 6 | c.878C>T | p.Pro293Leu | This study |

| 13 | 40 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 7 | c.1040A>C | p.Gln347His | This study |

| 130 | 0 | Complicated-ADHSP | SPAST | 7 | c.1082C>T | p.Pro361Leu | [41] |

| 133 | 35 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 7 | c.1054C>T | p.Gln352X | This study |

| 351 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 7 | c. 1091-1098delGGCCTGAG | p.Arg364fsX392 | This study | |

| 47 | 66 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 8 | c.1139T>A | p.Leu380His | [15] |

| 111 | 49 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 8 | c.1133T->G | p.Leu378Arg | This study |

| 180 | 54 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 8 | c.1172T>C | p.Leu391Pro | [42] |

| 273 | 1 | Complicated-SHSP | SPAST | 8 | c.1168A->G | p.Met390Val | [43] |

| 7 | 44 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 9 | c.1215-1219delTATAA | p. Asn405fsX441 | [7] |

| 22 | 42 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 9 | c.1174-1180delGCTAAG | p.Ala392fsX405 | This study |

| 23 | 35 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 9 | c.1226G>A | p.Ala409Thr | This study |

| 32 | 35 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 9 | c.1177-1180delAAAGCAGTA GCT | p.Lys393-Ala396del | This study |

| 52 | 45 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 9 | c.1210-1212delTTT | p.Phe404del | [44] |

| 80 | 38 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 9 | c.1210-1212delTTT | p.Phe404del | [44] |

| 98 | 29 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 9 | c.1192-93delGA/insT | Glu398fsX406 | This study |

| 179 | 10 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 9 | c.1192-93delGA/insT | Glu398fsX406 | This study |

| 363 | 2 | Pure_ADHSP | SPAST | 9 | C.1128A>C | p.Ser410Arg | This study |

| 135 | 47 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 10 | c.1306T>C | p.Ser436Pro | This study |

| 170 | 3 | Complicated-SHSP | SPAST | 10 | c.1276 C>G | p.Leu426Val | [7] |

| 373 | 10 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 10 | c. 1321G->A | p.Asp441Asn | This study |

| 50 | 2 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 11 | c.1387A>G | p.Thr463Ala | This study |

| 200 | 35 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 11 | c.1378c>A | p.Arg460Ser | [45] |

| 308 | 30 | Pure -ADHSP | SPAST | IVS11 | c.1414-2A>C | Exon 12 skipping | This study |

| 322 | 30 | Pure_ADHSP | SPAST | IVS11 | c.1414-1G>C | Exon 12 skipping | This study |

| 86 | 40 | Pure- ADHSP | SPAST | 12 | c.1439-1145delTACTTGT/insC | p.Val480fs | This study |

| 118 | 61 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 12 | c.1466C-> T | p.Pro489Leu | [46] |

| 177 | 20 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 12 | c.1492A<G | p.Arg498Gly | This study |

| 352 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 12 | c.1474C>T | p.Leu492Phe | This study | |

| 145 | 16 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | IVS12 | c1494-2A>G | presumed missplicing | This study |

| 178 | 1 | Pure-SHSP | SPAST | 13 | c.1507-1508insGGC | p.Lys503insArg | This study |

| 334 | 32 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 13 | c.1540A>G | p.Arg503Trp | [11] |

| 358 | 30 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 14 | c.1540A>G | p.Arg514Gly | [12] |

| 253 | 18 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 15 | c.1684C>T | p.Arg562X | [7] |

| 261 | 50 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | IVS15 | c.1687+1G/A | Ex15 skipping | [7] |

| 62 | 40 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | IVS15 | c.1687+1G/T | Ex15 skipping | This study |

| 103 | 40 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 17 | c.1793T-> C | p.Ile580Thr | This study |

| 112 | 56 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 17 | C.1739T-> C | p.Ile580Thr | This study |

| 212 | 35 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | 17 | c.1849T-> G | p.X617Glu | This study |

| 286 | 54 | Complicated-UHSP | SPAST | 17 | c.1849T-> G | p.X617Glu | This study |

| 310 | 36 | Pure- UHSP | SPAST | 17 | C.1838A-> C | p.Asp613Ala | This study |

| EXON DELETIONS | |||||||

| 199 | 20 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | - | EX10-16 deletion | [14] | |

| 225 | 14 | Pure-ADHSP | SPAST | - | Ex 6-7 deletion | This study | |

* ADHSP- Autosomal dominant spastic paraplegia; SHSP: apparently sporadic spastic paraplegia (including siblings with healthy parents); UHSP: Unkown familial history spastic paraplegia

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of SPAST and ATL1 domains showing the location of the mutations. The one letter code was used to identify the amino acid changes. Novel mutations are in bold.

SPAST missense mutations out of the AAA domain

Most of the missense mutations were in the AAA domain. Two novel missense changes (p. Pro293Leu, and p. Asp613Ala) were outside of the AAA domain, where missense mutations have been rarely found. The two amino acids were evolutionary conserved. The p.Pro293Leu proband was a 51-year-old man with progressive gait disorder starting at the age of 31, who has been confined to a wheelchair due to his spasticity (pure form) for the last two years. His 46-year-old sister, and one of his daughters (18 years old) also carried this mutation. They both presented brisk reflexes and Babinski's sign, but no spasticity and an almost normal gait. The p.Asp613Ala was found in a 45 years old man with a pure phenotype affecting only the lower limbs and the first symptoms at the age of 36 years. He did not report a family history of the disease, although no relatives were studied.

We also found a new SPAST missense variant (p.Ile328Leu) in a 15 years old male with complicated spastic paraplegia starting at the age of 18 months. This putative mutation was also found in his father's grandmother (asymptomatic), but the proband's father was not available for study. Although this variant was not found among the controls and involved a conserved amino acid, a bioinformatics analysis (SIFT v2. program, Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant; http://sift.jcvi.org/) indicated a non significant change in the protein function, and was thus classified as a change of uncertain pathogenic effect.

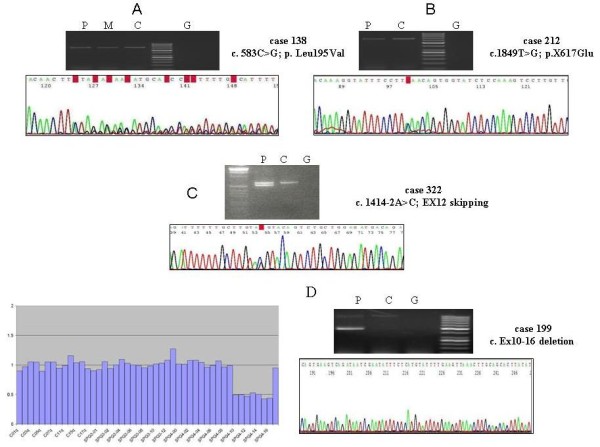

SPAST c.583C>G (exon 3) affected splicing

The c.583C>G (p.Leu195Val) was found in a 19 years old male with an onset at the age of 2 years and a phenotype complicated with neuropathy. He was from a family with ADSPH in which we confirmed the segregation of the disease with this mutation. This has been previously reported as a missense mutation, and the bioinformatic analysis (SIFT v2. program) indicated that this change would affect the protein function. However, the c.583C>G was four nucleotides from the 3' end of exon 3, and was also predicted to reduce the score of the splicing consensus site (Human Splicing Finder v. 2.4; http://www.umd.be/SSF). This mutation could thus result in an aberrant mRNA sequence. To confirm this, we isolated the mRNA from the patient's blood leukocytes and amplified the SPAST cDNA with primers for exons 2 and 7. The last 4 nucleotides of exon 3 were missed in the transcript, that would thus be translated into an aberrant protein (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

A) The cDNA from patient 138 (carrier of c.583C>G in exon 3 of SPAST) was synthesised from leukocytes mRNA. The sequencing of the fragment amplified with primers that matched exons 2 and 7 showed the deletion of the last 4 nucleotides of exon 3. B) The cDNA from patient 212 (X617Glu) was amplified with primers for exons 11 and 17 of SPAST, and the sequence showed similar electropherogram peaks for the two alleles. C) The cDNA of patient 322 was amplified with primers for exons 7 and 17 of SPAST, and the sequence showed the effect on splicing of the c.1414-1G>C mutation. D) MLPA of the SPAST gene in patient 199, showing the exons 10-16 deletion. The cDNA was amplified with primers that matched exons 9 and 17, and two PCR fragments were obtained. Sequencing of the smaller fragment confirmed the absence of exons 10 to 16. P = patient (cDNA); M = Patient's mother's (cDNA); C = Control (cDNA); G = Genomic DNA

SPAST sense mutation

We found a novel mutation in the SPAST stop codon, c.1849T>G (p.X617Glu) in two non related patients without known affected relatives. The mutated transcript was predicted to be translated into a 46 amino acids longer protein. To determine the stability of the mRNA containing this mutation, we synthesized the cDNA from RNA obtained from leukocytes of one of the patients and amplified and sequenced a PCR-fragment generated with primers that matched exons 11 and the 3' untranslated region (UTR). The two alleles gave equally intense sequence electropherogram peaks, suggesting that c.1849G did not increase the mRNA decay and was likely translated into a mutated protein (Figure 2B).

SPAST mutations affecting splicing

In addition to the above described c.583C>G in exon 3 of SPAST, we found five changes in intron splicing consensus nucleotides. The in silico analysis (Splice Site Prediction by Neural Network; http://www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/splice.html) indicated that the five changes would affect the pre-mRNA splicing. We could synthesize the cDNA from four of the patients, that was amplified with primers that matched exons 7 and 17, and exons 11 and 17. In all these cases two PCR-fragments were amplified, and the longer fragment corresponded to the wild type transcript while the shorter resulted from an exon skipping. In this way, we confirmed the existence of defective transcripts (Figure 2C).

Large SPAST deletions

We performed MLPA analysis in the 77 ADHSP cases who were negative for ATL1 and SPAST sequencing mutations. Two patients (2.5%) showed a significantly reduced amplification signal for exons 10-16, or exons 6-7 of SPAST. In the patient with a putative deletion of exons 10-16 we amplified the cDNA with primers that matched exons 9 and 17, and confirmed the skipping of exons 10-16 (Figure 2D). In this pedigree, the age at onset (third decade) was similar in the three affected members who were studied, and the oldest patient (an 81-year-old man) had been confined to a wheelchair for the previous five years.

ATL1 mutations

The ATL1 exons were sequenced in a total 88 patients with ADHSP and in 99 patients without a family history of HSP and an onset age ≤20 years. We found seven mutations and a variant with uncertain pathogenic effect in 11 patients (Table 2). Three were novel missense changes (p.His256Asp, p.Gln154Glu, and p.Phe413Val), while 5 had been reported. The p.Arg239Cys was a recurrent mutation found in 3 non related patients.

Table 2.

Mutations in the ATL1 gene.

| Case | onset age (Years) | Phenotype/Inheritance | GEN | Exon | Mutation | Protein | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 57.1 | 1 | Pure- SHSP | ATL1 | 4 | c.460 C>G | p.Gln154Glu | This study |

| 97 | 8 | Pure-ADHSP | ATL1 | 7 | c.715C>T | p.Arg239Cys | [47] |

| 102 | 4 | Pure-ADHSP | ATL1 | 7 | c.715C>T | p.Arg239Cys | [47] |

| 220 | 3 | Pure-ADHSP | ATL1 | 7 | c.715C>T | p.Arg239Cys | [47] |

| 279 | 5 | Pure-ADHSP | ATL1 | 7 | c.715C>T | p.Arg239Cys | [47] |

| 64 | 10 | Pure-ADHSP | ATL1 | 8 | c.757 G>A | p.Val253Ile | [25] |

| 159 | 5 | Pure-ADHSP | ATL1 | 12 | c.1483c>T | p.Arg495Trp | [25] |

| 110 | 17 | Pure-ADHSP | ATL1 | 12 | c.1319A->C | p.Asn440Thr | [25] |

| 232 | 6 | Pure-ADHSP | ATL1 | 12 | c.1237T->G | p.Phe413Val | This study |

| 233 | 16 | Complicated-ADHSP | ATL1 | 12 | c.1243 C->T | p.Arg415Trp | [40] |

Mutations p.Gln154Glu, (c.460 C>G), p. His256Asp (c.766C>A), and p.Phe413Val (c.1237T>G) are located in the guanilate binding protein domains. The p.Gln154Glu mutation was found in a patient with a pure phenotype and onset of symptoms in childhood. His son showed gait problems at the age of two years. The p.His256Asp patient was a 45 years old woman with the onset of symptoms at the age of 3 years and a progressive spastic paraplegia (Additional file 2, Figure S1). In her family, we identified mutation carriers who were asymptomatic at ages of 60 and 63 years, and this could thus be classified as a variant with uncertain pathogenic effect. Mutation p.Phe413Val was found in a patient with an onset age of 6 years and a complicated phenotype (neuropathy). Her mother was affected, but she was death and we could not confirm whether carried the mutation. None of the 77 ADHSP patients studied through MLPA showed evidence for large ATL1 deletions.

SPAST and ATL1 polymorphisms

We found several polymorphisms in the two genes (Additional file 1, Table S3). All the new polymorphisms were intronic, or exonic silent amino acid changes with one exception: c.844 T>A in exon 5 of SPAST (p.Ser282Thr). This missense change affected an amino conserved between species and was not found in any of the 400 controls. Although it could be considered a putative mutation, was in a patient with the p.Ser261X mutation (located also in exon 5). Segregation analysis to determine whether the two nucleotide changes were in different chromosomes was not possible. However, the electrophoretic pattern of bands after double restriction enzyme digestion (MnlI + MboI) of the exon 5 fragment indicated that the mutation was in cis with the c.844 A allele (data not shown). This suggested that this was likely a rare variant, rather than an HSP mutation. Two missense polymorphisms that have been proposed as modifiers of the clinical phenotype (p.Ser44Leu and p.Pro45Leu) were not found in our patients [29].

Genotype-phenotype correlation

The phenotype associated with SPAST and ATL1 mutations was pure in 48 (87%) and 10 (90%) of the index patients, respectively. We analysed all the available relatives of the 63 index cases with mutations, and identified a total of 54 SPAST and 15 ATL1 mutation carriers. A total of 13 mutation carriers (10 for SPAST and 3 for ATL1 gene) were asymptomatic at the time of our analysis. The mean onset age of the disease (index cases and relatives) was 34.5 (± 17.72) years for SPAST mutation carriers, and 7.67 (± 5.9 years) for ATL1 mutation carriers (p < 0.001). A difference was also observed between ATL1 mutation carriers and patients without SPAST/ATL1 mutations (7.67 ± 5.9 vs. 27.78 ± 20.238; p < 0.001). The mean duration of symptoms at the time of examination did not differ between patients with SPAST (14.5 ± 11.1) and ATL1 (18.78 ± 15.057) mutations. No difference in disease duration was observed between SPAST or ATL1 mutation carriers and patients without mutations.

Discussion

SPAST mutations (including large gene deletions) were found in 15% (54/370) of the patients, but this frequency increased to 31% (44/141) among patients with ADHSP. Most of the SPAST mutations were novel, and this was in agreement with previous reports that described a high rate of private mutations in this gene [30,10,15]. We found an ATL1 mutation in 6% of the patients studied for this gene, but this frequency could be underestimated because we did not include ADHSP patients with a SPAST mutation or patients with sporadic/uncertain HSP and an onset age >20 years. However, we think that the ATL1 mutation rate should be right because double mutated patients (SPAST + ATL1) have not been reported, and ATL1 mutations were rare among non-ADHSP patients with an onset age >20 years [22,25,26].

Considering the ADHSP cases, the mutational screening of SPAST and ATL1 identified a total of 54 mutation carriers, a frequency (38%) within the range reported in other populations [10,12,31,32]. Also in agreement with previous reports, the frequency of SPAST and ATL1 mutation carriers was much lower among patients with sporadic/uncertain HSP [12]. Four of the sporadic cases had a de novo mutation. A high rate of de novo mutational events for SPAST and ATL1 has been previously described, indicating that sporadic cases should also be screened for mutations in these genes after exclusion of other major neurological causes of spasticity [15,23,33-35].

SPAST mutations are mostly restricted to the AAA protein domain. It is thus remarkable that three of the missense mutations in our patients were out of this domain (p.Leu195Val, p.Pro293Leu, and p.Asp613Ala). In the case of ATL1 all the mutations were missense changes in the GTPase and transmembrane domains of atlastin, and would disrupt the normal protein folding and oligomerization [20,21]. The SPAST c.C583G variant was previously reported as a missense mutation (p.Leu195Val) [10]. However, this change was within the consensus splicing sequence of exon 3 and we confirmed its effect on pre-RNA splicing. Nucleotide changes in the last nucleotides of exons could result in both, normal and splicing defective transcripts [36-38]. Although we found an aberrant transcript we could not define whether the c.583 G resulted also in normal transcripts.

In the SPAST gene we also found one mutation in the stop codon (c.1849T>G; X617Glu), that would result in the translation of 46 amino acid beyond the stop codon. To our knowledge, this is the first sense mutation reported in this gene. The abolishment of a stop codon and the appearance of a longer ORF has been found in other hereditary diseases, such as the British Familial Dementia caused by a sense mutation in the ITM2B gene [39].

We performed MLPA analysis in 78 patients with ADHSP and we found two large deletions in the SPAST gene, which accounts for 2.5% of patients. In a recent work Shoukier et al. reported a similar frequency for this type of mutation [12]. However, previous studies reported a much higher frequency (18-23%) [13,15]. Additional studies are thus necessary to define the frequency of large deletions/duplications in the aetiology of HSP.

Finaly, SPAST and ATL1 mutations have been associated with variable penetrance, leading to heterogeneous HSP phenotypes in terms of onset age and clinical symptoms (pure vs. complicated) [40,15]. This heterogeneity could be partly explained by different mutated genes. As discussed above, we observed a significantly higher frequency of familial dominant HSP among ATL1 patients, compared to SPAST mutation carriers, and pure HSP was also more frequent among the patients with ATL1 mutations. However, phenotypic variability was also common among mutation carriers from the same family.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we reported the mutational spectrum of the SPAST and ATL1 genes in a large cohort of Spanish patients with spastic paraplegia. We found a mutation in 15% of the cases, and a frequency of mutation carriers significantly higher among ADHSP compared to sporadic cases. Thus, the genetic screening should be more relevant in patients (pure and complicated phenotypes) with a family history of the disease. However, the fact that a significant number of apparently sporadic cases had a mutation suggested that these patients should not be excluded from the genetic study. The mutational report could be of limited value to predict the phenotype associated to these mutations, as demonstrated by the heterogeneous behavior of most of the mutations.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All the authors contributed to this work by recruiting the patients, obtaining the clinical and analytical information, or performing the laboratory work. VA designated the work and analyzed the results. VA, ES-F, CB, M., BA, and AIC performed all the genetic analysis. VA and EC wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the submission of this manuscript.

Note

* Manuel Amorín, Eugenia Marzo-Sola, Carlos H. Lahoz, Pia Gallano, Concepción Alonso-Cerezo, Rafael Palencia-Luaces, Eduardo Gutiérrez- Rivas, Rogelio Simón, Loreto Martorell, Eduardo López-Laso, José M. Asensi, Luis Hernández- Echebarria, Yolanda Morgado, Alonso González-Masegosa, Juan J. Garcia- Peñas, Irene Catalina-Alvarez, José L. Muñoz-Blanco, Miguel Fernández-Burriel, Juan B. Espinal, Mariano Aparicio- Blanco, Jon Infante, María Vázquez-Espinar, Elena Maside

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

Supplementary tables and supplementary figure 1 legendl for Alvarez et al. This file contains information about PCR primers, polymorphisms detected and legend of supplementary figure.

supplementary FIGURE1 for Alvarez et al. This file contains a figure showing several examples of mutations detected.

Contributor Information

Victoria Álvarez, Email: victoria.alvarez@sespa.princast.es.

Elena Sánchez-Ferrero, Email: tohelli@hotmail.com.

Christian Beetz, Email: Christian.Beetz@med.uni-jena.de.

Marta Díaz, Email: martaediaz@yahoo.es.

Belén Alonso, Email: belen.montanel@hotmail.com.

Ana I Corao, Email: anacora@hotmail.com.

Josep Gámez, Email: pepgamez@gmail.com.

Jesús Esteban, Email: jesteban.hdoc@salud.madrid.org.

Juan F Gonzalo, Email: juanchogonzalo@yahoo.es.

Samuel I Pascual-Pascual, Email: ipascualp.hulp@salud.madrid.org.

Adolfo López de Munain, Email: ADOLFO.LOPEZDEMUNAINARREGUI@osakidetza.net.

Germán Moris, Email: gmorist@gmail.com.

Renne Ribacoba, Email: rribacoba@gmail.com.

Celedonio Márquez, Email: celedoniomarquez@gmail.com.

Jordi Rosell, Email: jordi.rosell@ssib.es.

Rosario Marín, Email: MAJESUS.GARCIABARCINA@osakidetza.net.

Maria J García-Barcina, Email: genetica.hpm.sspa@juntadeandalucia.es.

Emilia del Castillo, Email: genemalaga.hch.sspa@juntadeandalucia.es.

Carmen Benito, Email: victoriaalvaremartinez@yahoo.es.

Eliecer Coto, Email: eliecer.coto@sespa.princast.es.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from Spanish Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias PI08/0915 (European FEDER founds) to V.A. E.S-F. was a fellowship from FICYT-Principado de Asturias. The authors thank the patients and family members for their participation in this study. Authors wish to thank Fundación Parkinson Asturias and Obra Social CAJASTUR for their support.

References

- Harding AE. Classification of the hereditary ataxias and paraplegias. Lancet. 1983;1:1151–1155. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(83)92879-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevanin G, Ruberg M, Brice A. Recent advances in the genetics of spastic paraplegias. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2008;8:198–210. doi: 10.1007/s11910-008-0032-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas S, Proukakis C, Crosby A, Warner TT. Hereditary spastic paraplegia: clinical features and pathogenetic mechanisms. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:1127–38. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70258-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dursun U, Koroglu C, Kocasoy Orhan E, Ugur SA, Tolun A. Autosomal recessive spastic paraplegia (SPG45) with mental retardation maps to10q24.3-q25.1. Neurogenetics. 2009;10:325–31. doi: 10.1007/s10048-009-0191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errico A, Ballabio A, Rugarli EI. Spastin, the protein mutated in autosomal dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia, is involved in microtubule dynamics. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:153–63. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SH, Zhu PP, Parker RL, Blackstone C. Hereditary spastic paraplegia proteins REEP1, spastin, and atlastin-1 coordinate microtubule interactions with the tubular ER network. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1097–110. doi: 10.1172/JCI40979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonknechten N, Mavel D, Byrne P, Davoine CS, Cruaud C, Bönsch D. et al. Spectrum of SPG4 mutations in autosomal dominant spasticparaplegia. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:637–44. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.4.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauter S, Miterski B, Klimpe S, Bönsch D, Schöls L, Visbeck A. et al. Mutation analysis of the spastin gene (SPG4) in patients in Germany with autosomal dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia. Hum Mutat. 2002;20:127–32. doi: 10.1002/humu.10105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrono C, Scarano V, Cricchi F, Melone MA, Chiriaco M, Napolitano A. et al. Autosomal dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia:DHPLC-based mutation analysis of SPG4 reveals eleven novel mutations. Hum Mutat. 2005;25:506. doi: 10.1002/humu.9340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crippa F, Panzeri C, Martinuzzi A, Arnoldi A, Redaelli F, Tonelli A. et al. Eight novel mutations in SPG4 in a large sample of patients with hereditary spastic paraplegia. ArchNeurol. 2006;63:750–5. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.5.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depienne C, Tallaksen C, Lephay JY, Bricka B, Poea-Guyon S, Fontaine B. et al. Spastin mutations are frequent in sporadic spastic paraparesis and their spectrum is different from that observed in familial cases. J Med Genet. 2006;43:259–65. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.035311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoukier M, Neesen J, Sauter SM, Argyriou L, Doerwald N, Pantakani DV. et al. Expansion of mutation spectrum, determination of mutation cluster regions and predictive structural classification of SPAST mutations in hereditary spastic paraplegia. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:187–94. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beetz C, Nygren AO, Schickel J, Auer-Grumbach M, Bürk K, Heide G. et al. High frequency of partial SPAST deletions in autosomal dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia. Neurology. 2006;67:1926–30. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000244413.49258.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depienne C, Fedirko E, Forlani S, Cazeneuve C, Ribaï P, Feki I. et al. Exon deletions of SPG4 are a frequent cause of hereditary spastic paraplegia. J Med Genet. 2007;44:281–284. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.046425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erichsen AK, Inderhaug E, Mattingsdal M, Eiklid K, Tallaksen CM. Seven novelmutations and four exon deletions in a collection of Norwegian patients with SPG4 hereditary spastic paraplegia. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:809–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitne-Neto M, Kok F, Beetz C, Pessoa A, Bueno C, Graciani Z. et al. A multi-exonic SPG4 duplication underlies sex-dependent penetrance of hereditary spastic paraplegia in a large Brazilian pedigree. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15:1276–1279. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrono C, Casali C, Tessa A, Cricchi F, Fortini D, Carrozzo R. et al. Missense and splice site mutations in SPG4 suggest loss-of-function in dominant spastic paraplegia. J Neurol. 2002;249:200–5. doi: 10.1007/PL00007865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charvin D, Cifuentes-Diaz C, Fonknechten N, Joshi V, Hazan J, Melki J. et al. Mutations of SPG4 are responsible for a loss of function of spastin, an abundant neuronal protein localized in the nucleus. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:71–8. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solowska J, Garbern JY, Baas PW. Evalution of loss of function as an explanation for SPG4-based hereditary spastic paraplegia. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:1–13. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namekawa M, Muriel MP, Janer A, Latouche M, Dauphin A, Debeir T. et al. Mutations in the SPG3A gene encoding the GTPase atlastin interfere with vesicle trafficking in the ER/Golgi interface and Golgi morphogenesis. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;35:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muriel MP, Dauphin A, Namekawa M, Gervais A, Brice A, Ruberg M. Atlastin-1, the dynamin-like GTPase responsible for spastic paraplegia SPG3A, remodels lipid membranes and may form tubules and vesicles in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Neurochem. 2009;110:1607–1616. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauter SM, Engel W, Neumann LM, Kunze J, Neesen. Novel mutations in the Atlastin gene (SPG3A) in families with autosomal dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia and evidence for late onset forms of HSP linked to the SPG3A locus. Hum Mutat. 2004;23:98. doi: 10.1002/humu.9205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova N, Claeys KG, Deconinck T, Litvinenko I, Jordanova A, Auer-Grumbach M. et al. Hereditary spastic paraplegia 3A associated with axonal neuropathy. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:706–13. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.5.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel A, Fonknechten N, Hofer A, Dürr A, Cruaud C, Voit T. et al. Early onset autosomal dominant spastic paraplegia caused by novel mutations in SPG3A. Neurogenetics. 2004;5:239–43. doi: 10.1007/s10048-004-0191-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dürr A, Camuzat A, Colin E, Tallaksen C, Hannequin D, Coutinho P. et al. Atlastin1 mutations are frequent in young-onset autosomal dominant spastic paraplegia. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:1867–72. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.12.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namekawa M, Ribai P, Nelson I, Forlani S, Fellmann F, Goizet C. et al. SPG3A is the most frequent cause of hereditary spastic paraplegia with onset before age 10 years. Neurology. 2006;66:112–4. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000191390.20564.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallaksen CM, Dürr A, Brice A. Recent advances in hereditary spastic paraplegia. Curr Opin Neurol. 2001;14:457–463. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200108000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall LP, Coldham NG, Woodward MJ. Detection of mutations in Salmonella enterica gyrA, gyrB, parC and parE genes by denaturing high performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) using standard HPLC instrumentation. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:619–23. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svenson IK, Kloos MT, Gaskell PC, Nance MA, Garbern JY, Hisanaga S. et al. Intragenic modifiers of hereditary spastic paraplegia due to spastin gene mutations. Neurogenetics. 2004;5:157–64. doi: 10.1007/s10048-004-0186-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proukakis C, Auer-Grumbach M, Wagner K, Wilkinson PA, Reid E, Patton MA. et al. Screening of patients with hereditary spastic paraplegia reveals seven novel mutations in the SPG4 (Spastin) gene. Hum Mutat. 2003;21:170. doi: 10.1002/humu.9108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott CJ, Burness CE, Kirby J, Cox LE, Rao DG, Hewamadduma C. et al. Clinical features of hereditary spastic paraplegia due to spastin mutation. Neurology. 2006;67:45–51. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000223315.62404.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro JL, Miller-Fleming L, Thieleke-Matos C, Magalhães P, Cruz VT, Coutinho P. et al. Novel SPG3A and SPG4 mutations in dominant spastic paraplegia families. Acta Neurol Scand. 2009;119:113–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainier S, Sher C, Reish O, Thomas D. Fink JK De novo occurrence of novelSPG3A/atlastin mutation presenting as cerebral palsy. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:445–447. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scuderi C, Fichera M, Calabrese G, Elia M, Amato C, Savio M, Borgione E. et al. Posterior fossa abnormalities in hereditary spastic paraparesis with spastin mutations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:440–443. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.154807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molon A, Montagna P, Angelini C, Pegoraro E. Novel spastin mutations and their expression analysis in two Italian families. Eur J Hum Genet. 2003;11:710–713. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svenson IK, Ashley-Koch AE, Gaskell PC, Riney TJ, Cumming WJ, Kingston HM. et al. Identification and expression analysis of spastin gene mutations in hereditary spastic paraplegia. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:1077–85. doi: 10.1086/320111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riveira-Munoz E, Chang Q, Godefroid N, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ, Dahan K. et al. Transcriptional and functional analyses of SLC12A3 mutations: new clues for the pathogenesis of Gitelman syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1271–83. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006101095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coto E, Arriba G, García-Castro M, Santos F, Corao AI, Díaz M. et al. Clinical and analytical findings in Gitelman's syndrome associated with homozygosity for the c.1925 G>A SLC12A3 mutation. Am J Nephrol. 2009;30:218–21. doi: 10.1159/000218104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal R, Frangione B, Rostagno A, Mead S, Révész T, Plant G. et al. A stop-codon mutation in the BRI gene associated with familial British dementia. Nature. 1999;399:776–81. doi: 10.1038/21637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico A, Tessa A, Sabino A, Bertini E, Santorelli FM, Servidei S. Incomplete penetrance in an SPG3A-linked family with a new mutation in the atlastin gene. Neurology. 2004;62:2138–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000127698.88895.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnery PF, Keers SM, Holden MJ, Ramesh V, Dalton A. Infantile hereditary spastic paraparesis due to codominant mutations in the spastin gene. Neurology. 2004;63:710–2. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000135346.63675.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertelli M, Cecchin S, Lorusso L, Sidoti V, Fabbri A, Lapucci C. et al. Identification of a novel mutation in the spastin gene (SPG4) in an Italian family with hereditary spastic paresis. Panminerva Med. 2006;48:193–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang B, Zhao G, Xia K, Pan Q, Luo W, Shen L, Long Z. et al. Three novel mutations of the spastin gene in Chinese patients with hereditary spastic paraplegia. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:49–55. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Ki CS, Kim HJ, Kim JW, Sung DH, Kim BJ. et al. Mutation analysis of SPG4 and SPG3A genes and its implication in molecular diagnosis of Korean patients with hereditary spastic paraplegia. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:1118–1121. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.7.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braschinsky M, Tamm R, Beetz C, Sachez-Ferrero E, Raukas E, Lüüs SM. et al. Unique spectrum of SPAST variants in Estonian HSP patients: presence of benign missense changes but lack of exonic rearrangements. BMC Neurol. 2010;10:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-10-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer IA, Hand CK, Cossette P, Figlewicz DA, Rouleau GA. Spectrum of SPG4 mutations in a large collection of North American families with hereditary spastic paraplegia. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:281–286. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson PA, Hart PE, Patel H, Warner TT, Crosby AH. SPG3A mutation screening in English families with early onset autosomal dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia. J Neurol Sci. 2003;216:43–45. doi: 10.1016/S0022-510X(03)00210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary tables and supplementary figure 1 legendl for Alvarez et al. This file contains information about PCR primers, polymorphisms detected and legend of supplementary figure.

supplementary FIGURE1 for Alvarez et al. This file contains a figure showing several examples of mutations detected.