This article analyzes the history of policies by New York City government and police enforcement strategies to socially control marijuana use and sales in public locations—that is in the streets; parks; and quasi-public settings such as bars, restaurants, and stores. This particular article is organized around the laws, regulations, and enforcement associated with two central civic norms: (1) Users should not smoke marijuana in public settings (streets, parks) or in quasi-public settings such as stores, bars, restaurants, offices, etc. and (2) Persons should not sell marijuana in public and quasi-public settings. Occasionally, the authors make reference to marijuana use and sales in private settings, but the primary focus of marijuana policy makers and enforcement activities has always been directed towards those activities occurring in public locations.

This analysis begins with an overview of the history of marijuana policy and the growth of marijuana use and sales in public settings. Three different historical eras are largely framed by the passage of legislation and/or the development of new enforcement policies in New York City: (1) Marijuana included under statutes as a narcotic (same as heroin and cocaine) (1950-1974), (2) Marijuana “decriminalized” and enforcement limited (1975-1995), and (3) Marijuana decriminalized, but quality-of-life enforcement arrests large numbers of marijuana smokers (1996-present).

Authors’ Background

This analysis crosscuts several current and numerous previous projects by the senior author who has been active in drug research in New York City for over 35 years. Beginning with a study of marijuana use among college students in the New York area (Johnson, 1973), subsequent articles with his colleagues have focused on marijuana users and sellers (Chaiken & Johnson, 1988; Dunlap, Johnson, Sifaneck, & Benoit, 2005; Golub, Johnson, & Dunlap, 2005; Johnson & Uppal, 1980; Johnson, Williams, Dei, & Sanabria, 1990; Johnson, Golub et al., 2006; Sifaneck, Johnson, & Dunlap, 2005) and especially upon persons arrested in Manhattan for any offense (Golub, 2006; Golub & Johnson, 1999, 2001a, 2001b, 2002, 2004; Johnson, Golub, & Dunlap, 2006). Some studies have analyzed whether marijuana arrestees are different than other offenders in Manhattan (Golub, Johnson, Taylor, & Liberty, 2002; Golub, Johnson, Dunlap, & Sifaneck, 2004; Golub, Johnson, Taylor, & Eterno, 2003). One study focused upon the impacts of quality-of-life policing initiatives (Golub et al., 2002, 2003, 2004; Johnson, Taylor, & Golub, 2006); this involved close collaboration with the New York City Police Department (NYPD) and extensive reading about major changes in NYPD strategies and tactics. During the 1980s to the present time, various research projects have been funded that rely upon ethnographic research staff to conduct ongoing studies among persons involved in street drug markets and collect information about typical prices for various cannabis products. This article and several companion papers (Golub, Johnson, & Dunlap, 2005; Johnson, Bardhi et al., 2006; Johnson, Ream et al., in press; Ream, Johnson, Sifaneck, & Dunlap, 2006) are emerging from a 5-year investigation about the important role of blunts (marijuana smoked in a cigar shell) within marijuana subculture. Previous articles have not specified what policies the police and the courts in New York City are following when enforcing marijuana statutes. This article addresses this complex topic directly.

Limitations of Data Available

The proactive policing of marijuana smoking and sales that emerged in the 1990s had a variety of outcomes that cannot be documented with existing data. [Note: Marijuana arrest statistics provide general findings that are provided elsewhere (Golub, Johnson, & Dunlap, 2006, in press).] This is both because police may not keep such data, and the phenomena of interest would generate no (zero) official statistics. That is, to the extent that blunts (marijuana consumed in a cigar shell) and marijuana smokers are complying with civic norms by consuming in private locales, they would generate no arrests or “stops” that police could count. Likewise, police do not keep good statistics upon the retail prices of marijuana nor recognize the marijuana subculture distinction between blunt and joint consumers (Ream et al., 2006). Rather, the following draws upon the authors’ observations of changes and conversations with police officials about changes in the New York City street drug scene over the past three decades. Citations to appropriate publications are included.

A key analytic theme is that public policies towards marijuana and enforcement activities in New York City have seldom been specifically directed at marijuana. Rather, they have been driven by larger political concerns about crime, combating hard drug sales, and reduction of disorder in public locations. That is, it is difficult to locate specific policies or even moral entrepreneurs (Becker, 1963) in New York City who have specifically targeted marijuana use or sales as a separate and distinct policy issue. This also means that the following summary of marijuana controls in the city cannot be easily separated out from the larger policy concerns about hard drug use, crime control, and public order maintenance.

We first analyze the history of how these laws and civic norms have been defined, enforced, and especially the impact that quality-of-life policing has had upon marijuana use and selling in public settings in the city. Top policy makers in New York City and State have never socially constructed marijuana as a “top” drug problem. Rather, the emphasis in New York City and State has been directed at heroin users, first in 1964 to 1975, and especially at crack cocaine in 1985 through 1995 (and to the present time). None of the policies described below appear to have had a measurable impact on the rates of marijuana use as reported in population-based surveys. Furthermore, evidence from several national surveys suggests that marijuana use rates among arrestee in New York City appear to be very close to the national average1 (ADAM, 2003; Golub & Johnson, 2001; Golub, Liberty, & Johnson, 2005). New York City is well below the national marijuana prevalence among schoolage populations (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2004).

The policing policies reviewed below have had an important impact on the patterns and visibility of marijuana use in public locations; upon its sale; prices and quantities sold; and upon the extent of tolerance of public marijuana use/sale among the general population, especially by nonusers. As documented below, only a few persons were arrested for marijuana smoking, but in recent years, very large numbers have been arrested, convicted, and given dispositions of low severity for marijuana possession and sale offenses. So these public policies have in fact had important impacts on the ways in which marijuana is used and sold in the city, especially in its public locations.

1937-1974: Marijuana as a Narcotic Drug

From 1937 to 1974, New York State penal statutes included marijuana as a felony criminal offense. The possession or transfer of any amount of marijuana in a private or public location was an arrestable offense; those convicted could be sentenced to jail or prison. These laws remain true for possession or sale of heroin, cocaine, crack, and some other drugs in New York State at the current time. During the 1960s and 1970s, thousands of persons were being arrested for heroin possession and sales, with many imprisoned for long time periods. During the 1950-1974 period, the civic norms against use or sale of marijuana in public (and private) settings were labeled as a criminal offense.2 If police discovered someone who was in possession of marijuana, the violator would be formally arrested and handcuffed, spend time in detention awaiting arraignment, and likely receive a jail or probation sentence. Yet few marijuana arrestees went to prison unless arrested with large quantities of marijuana.3

During the 1960s, however, marijuana initiation and use was expanding rapidly among the baby-boom generation (those born 1945-1954), so that thousands of otherwise conventional and middle class youths and young adults were being arrested and convicted for marijuana possession. Several academic sources (Goode, 1970; Kaplan, 1970) as well as a major report by the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse (1972) recommended a decriminalization policy towards possession and sale of small amounts of marijuana. Many marijuana users, activists, ordinary citizens, and legislators whose children had been arrested for marijuana charges supported passage of the marijuana decriminalization policy. New York City legislators were among the leaders who passed legislation to decriminalize marijuana to a limited extent. In the 1970s, the NYPD was still reeling from documentation of widespread police corruption associated with payoffs to police officers by drug dealers (Knapp Commission, 1972). Such corruption was documented again by the Mollen Commission (1994) several years later.

1975-1994: Marijuana Decriminalized and Enforcement Limited

New York State became one of 12 American states to remove cannabis violations from its narcotics statutes (Penal Law of the State of New York, 2005, Section 220) and create separate statutes for possession or sale of marijuana and cannabis products (Section 221). Under these decriminalized statutes, persons can possess and sell small amounts of marijuana in private settings; the primary sanction is a fine. The statute (Penal Law of the State of New York 221.10 — a class B misdemeanor) provides for criminal possession of marijuana for small amounts (under 25 grams) an offense. PL221.10 also specifically includes possession of “marihuana in a public place … and such marihuana is burning or open to public view” (e.g., smoking marijuana in public). Such activity was defined as an arrestable and criminal offense. Likewise, the sale of “marihuana … of an aggregate weight of two grams or less; or one cigarette containing marihuana” is a B misdemeanor (PL221.35). Conviction of a B misdemeanor is usually punished by a fine of $100-$500 because most marijuana arrestees after 1995 have been charged under 221.10—Criminal Marijuana Possession in the Fifth Degree (MPV)—which could also indicate Marijuana in Public View. The ethnographic evidence from both police and arrested persons is that they have been caught smoking marijuana in a public place; usually only a part of a joint or blunt is seized as evidence and is typically less than 2 grams.

Ever since (1975-present), New York police rarely attempt to locate and “raid” homes or private locations,4 except where multiple kilograms of marijuana may be held, or marijuana growing is alleged. Virtually all cannabis-related enforcement by the NYPD since 1975 has been directed at the possession or sale of marijuana in public places (e.g., streets, parks) or in quasi-public settings (e.g., storefronts, clubs, shopping centers, offices, bars, clubs).

This analysis necessarily relies upon legal statutes, terminology, procedures, and processing of marijuana cases by the NYPD and courts (these are more fully explained in the Appendix). An especially important distinction is between a Desk Appearance Ticket (DAT), which involves a criminal charge (such as MPV) and a C-summons, which is given for a wide range of other minor (noncriminal) code violations such as transit fare evasion, open alcohol containers, public urination, and trespassing—many of which were later to be called quality-of-life offenses. Both DATs and C-summons would appear similar to a recipient (as would traffic tickets); moreover both require the person to appear at a criminal court arraignment for disposition about a month later.

Limited Marijuana Enforcement in New York City (1975-1995)

During this period, enforcement against marijuana users or sellers was among the “lowest” priorities of the NYPD—in part because violent and property crime soared, homicides increased, and sales of heroin and cocaine expanded greatly (Blumstein & Wallman, 2006; Johnson, Golub, & Dunlap, 2006). Massive drug enforcement effort was primarily directed at heroin and especially at crack sellers during the 1985-1999 period.

Police officers had the discretion to stop marijuana smokers or sellers and discard their marijuana but not initiate the arrest process. To avoid possible corruption of (and payoffs to) police officers, NYPD policy also discouraged beat officers from making drug-related arrests, including those for marijuana (See Bratton with Knobler, 1996; Kelling & Coles, 1996; Maple, 1999). In 1990-1992, under 1,000 MPV arrests were recorded in the entire city (Graph 1). In the early 1980s, some rookie officers believed that they would be kidded by other officers if they arrested someone for a misdemeanor marijuana charge (McCabe, 2005).

Under decriminalization statutes, police enforcement of marijuana-related behaviors changed substantially. Marijuana offenses (especially smoking marijuana in public or MPV and sales of loose joints) in public places were very low-level (A and B) misdemeanors that were usually plead down to violations with the guilty person being fined. The police managers also chose not to arrest persons who committed the most common marijuana offenses—especially marijuana smoking—in public locations. Between 1975 and 1994, NYPD policy required that violations of Penal Law 221 were eligible for C-summonses when the person had proper identification and a radio check indicated no outstanding warrants or not wanted for a crime. Smoking in public and possession of more than 25 grams required an arrest, so did possession of 2 to 8 ounces (misdemeanor A). People violating these sections of the Penal Law did not qualify for C-summonses. Persons arrested for these offenses (MPV) were eligible for a Desk Appearance Ticket (DAT) upon showing proper ID, had no outstanding warrants, and were not wanted. Police policy sometimes permitted DATs to be issued for common misdemeanors (A) such as possession of up to 8 ounces. NYPD policy prohibited DATs for sale of any amount of marijuana of 25 grams or more.

The arrested person received a DAT. On a future date, the violator was to appear in a misdemeanor criminal court, typically received a disposition, was usually found guilty, was given an ACOD, paid a fine, or had another disposition. Persons receiving DATs are formally arrested, given a ticket at the precinct, and released but are not detained at the borough’s central criminal court with detention facilities (see Appendix).

Police came to refer to DATs as “Disappearance Tickets” since only about half were ever answered; the “no show” violator was rarely sought out and/or punished. Compounding this was a requirement (in the 1980s and early 1990s) that arresting officers who issued DATs were still required to go to court, meet with a prosecutor, and provide an affidavit (a sworn criminal complaint) for court processing. These appearances by police officers were required before the return dates of the DATs and often were missed or forgotten, etc., leaving the DAT undocketed and unsworn and the defendant off the hook criminally (if they even appeared). The failure of the arresting officer to appear often meant that the judge dismissed the case. This was particularly the case with marijuana offenses because no other person was a complainant. Police and court procedures at the time often released marijuana sellers and smokers before the arresting officer was back on the street.

Many street-level marijuana arrestees receiving DATs rapidly discarded them and effectively ignored this type of sanction (Bratton with Knobler, 1998; Kelling & Coles, 1996; Maple, 1999). Only if the person was subsequently arrested for a misdemeanor or felony offense might the failure to appear and/or pay this marijuana-related fine become an additional charge against the offender, but this prior additional charge seldom increased the actual criminal sanction imposed by the judge.

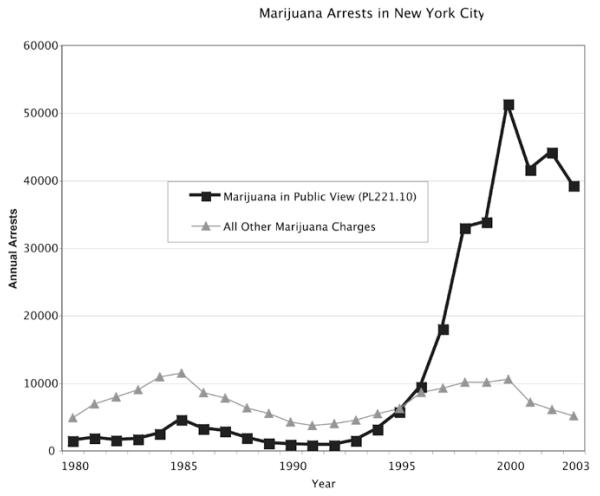

From the perspective of high-ranking police officials and policy makers, marijuana users and sellers (and others arrested on misdemeanor B charges) were “pushing the envelope” (effectively challenging) the legitimacy of the civic norm by actively using and regularly selling marijuana in public locations. Indeed, this NYPD enforcement policy of issuing DATs against marijuana smokers and especially against street sales of loose joints and low-cost bags of marijuana was widely perceived as “not serious” by routine violators. The fines imposed by judges became an accepted part of “doing business” for marijuana sellers (Kelling & Coles, 1996). From the police and citizen point of view in the 1990s, Manhattan courts/judges were notorious for dismissing marijuana cases. When the NYPD tried to clean up Washington Square Park in the mid-1990s, hundreds of marijuana sellers were arrested for such sales but received sentences of nothing more than “time served” or at the most a nominal fine (the maximum was $100 at the time) (Bratton & Knobler, 1998; Maple, 1999). The following suggests the possible consequences of very limited enforcement or limited sanctions for enforcing the civic norms based upon a prohibition policy towards marijuana. This created a great source of frustration for NYPD brass. An unwritten, but widely understood, police policy discouraged low-level marijuana arrests because the penalties weren’t worth police time and the risks of corruption. As Figure 1 below demonstrates, very few MPV arrests occurred between 1980 and 1994.

Figure 1.

Marijuana Arrests in New York City

The social visibility of marijuana selling and smoking expanded dramatically. A substantial growth in number of sellers of marijuana (many also sold cocaine and crack as well) in public locations occurred throughout the 1970s, 1980s, and well into the 1990s (Johnson, Golub, & Fagan, 1995). With the decline of the city’s manufacturing sector that provided steady low-wage work, thousands of low-income persons, especially from minority backgrounds, were effectively unemployed—so selling marijuana was a low-risk and more profitable line of work for many (Johnson et al., 1990).

In the 1970s and 1980s, the proliferation of drug sellers in New York City effectively shifted the “effective” standards—so that the citizenry accepted the presence of marijuana sellers and ignored marijuana smoking in public locations. Thousands of young persons, who were usually excluded from legal jobs, chose to engage in marijuana (and other) sales as their primary occupational activity and major form of income generation. In addition, large numbers of African-American and Hispanic young persons sold marijuana in public places. Virtually every street in low-income neighborhoods and every city park had one to several persons selling “loose joints” ($1) and “nickel” ($5) or “dime” ($10) bags of marijuana (and often other illegal drugs) (Johnson et al., 1990; Johnson, Golub, & Dunlap, 2006).

Around 1980, the civic norm had been substantially undermined by sellers—marijuana had become a commodity that was equally or more widely available in the street culture than alcohol or tobacco products. The more active sellers aggressively approached almost all passersby and hawked (invited them to buy) loose joints. Most nonusing citizens were often offered an opportunity to purchase marijuana by one or several sellers. Marijuana consumers could choose from among a large number of sellers; many sellers were available in the streets or parks, others in storefronts; some could be contacted for delivery. Marijuana users and sellers were also perceived as the least threatening among a much larger pool of hard drug users/sellers and criminal offenders in the city’s street markets. Marijuana smoking and sales in public places was widely tolerated by nonusers and public policy makers—the latter had more serious problems to address.

In addition, West Indian immigrants, especially from Jamaica, and often claiming to be Rastafari, were especially effective at growing marijuana in the West Indies and importing large quantities of it into New York City, where they sold it through a network of storefronts to consumers (Hamid, 2002). Many other small stores permitted someone to sell marijuana from their space. These storefronts often presented a legal appearance (as beauty stores, bars, record shops, convenience stores), but marijuana sales provided most of their revenues and enabled marijuana sellers to pay much higher rents than regular commercial tenants. In marijuana argot, “storefront,” meant a location where marijuana (and often other drugs) could be purchased, while a “store” referred to a legitimate enterprise with no marijuana/drugs available (Johnson, Golub et al., 2006).

All during the 1980s, levels of crime in the city continued to surge to new heights, led by the explosive number of crack sellers and users after 1985. By 1988-1992, crack sellers in public locations had greatly surpassed marijuana sellers in numbers; many sold both drugs (Johnson et al., 1995; Johnson, Dunlap, & Tourigny, 2000). Police enforcement was primarily directed against street-level crack sellers and crews and not at marijuana sellers. Although thousands of crack/cocaine sellers were arrested, jailed, and imprisoned, many more were sentenced to probation and/or mandated to drug treatment. Crews of crack and/or heroin sellers were often armed with handguns and other weapons; these groups effectively controlled whole blocks in some neighborhoods (Blumstein & Wallman, 2006; Johnson et al., 1990; Johnson, Golub et al., 2006).

From the perspective of many business elites and citizen groups, the perceived breakdown of civic norms was equated with public disorder and high levels of fear. New York City was alleged to be the “crime capitol,” “murder capitol,” and “ungovernable.” David Dinkins became the first African-American mayor of New York City in 1988, yet crime rates and levels of disorder were so great in many neighborhoods that business and civic groups forced him to expand the number of police officers. The mayoral election in 1992 primarily focused upon which candidate could better control crime and rampant drug selling, especially in public settings. The incumbent, David Dinkins, was defeated by Republican Rudolph Giuliani (in a predominately democratic city)—because he promised to “take back the streets” from drug sellers and criminals and to improve the “quality-of-life” in the city.

1995-Present: Marijuana Decriminalized, Public Users and Sellers Arrested

Mayor Giuliani and his three police commissioners greatly changed the enforcement practices against all drugs and many other forms of criminal activity and a wide range of behaviors that violated civic and criminal codes.5 Three important policy shifts in policing had especially important impacts upon marijuana users and sellers in public settings: (1) targeting drug sellers, (2) nuisance abatement, and (3) quality-of-life policing. The philosophy, planning, strategies, and their implementation have been delineated in several publications (Bratton with Knobler, 1998; Eterno, 2001, 2003; Guiliani with Kurson, 2002; Kelling & Coles, 1996; Kelling & Sousa, 2001; Kerik, 2001; Maple, 1999; McCabe, 2005; NYPD, 1994, 1999; Silverman, 1999, 2002; Wilson & Kelling, 1982). These zero tolerance policing policies, and especially their implementation, have also been severely criticized for disproportionately focusing upon minority communities, arresting and imprisoning thousands of poor minorities, violating individual rights, unnecessary stop/searches, and imposing severe sanctions for minor offenses (Amnesty International, 1999; Cohen, 1999; Cunneen, 1999; Dixon & Coffin, 1999; Flynn, 1999; Greene, 1999; Harcourt, 1998, 2002; Maher & Dixon, 1999; McArdle & Erzen, 2001; Spitzer, 1999). The existence of ethnic disparities in marijuana-related arrests and dispositions in New York City is documented elsewhere (Golub & Johnson, 2006).

Major policing initiatives confronted marijuana users/sellers. The NYPD developed at least 10 specific policies to combat major and minor crimes in the city. Three of these initiatives resulted in frequent police contacts and arrests of marijuana smokers and sellers in public locations: (1) suppression of street-level drug sellers, (2) nuisance abatement, and (3) quality-of-life policing. These policies were initially pilot-tested in a few precincts and then expanded to the entire police force in the city. This section also documents the massive increases in MPV arrests during the last half of the 1990s and into the 21st century.

Suppression of Street-Level Drug Sellers

The NYPD developed a range of strategies and tactics that targeted everyone selling illegal drugs in public settings. The NYPD Police Strategy (1994) No. 3: “Driving Drug Dealers Out of New York City,” had the explicit goal of “driving open-air drug activity off the streets of targeted areas, then closing, and where possible seizing, the inside drug trafficking locations … to reclaim and hold geographical areas of the city with and for the people who live there” (Bratton with Knobler, 1998). This policy was vigorously and systematically implemented in the following decade. Tactically, NYPD undercover officers were, and are, excellent disguise artists, sometimes sporting tattoos, shaved heads, and even real dreadlocks. Organized squads are capable of making many buy-bust operations a day. The police also debrief many persons arrested for new leads about key persons, organizational structure, and descriptions of operations (Bratton with Knobler, 1998; Maple, 1999). The NYPD pursued a multidimensional approach: target the organization behind drug selling operations, target and close the locations where drugs are sold, and stabilize the location so that drug selling does not return to that area (McCabe, 2005).

The NYPD especially pursued and systematically dismantled businesslike crack distribution groups controlled by one or several persons in a given community (Curtis, 1998; Curtis & Wendel, 2000). Persons managing distribution groups and many of their coworkers were arrested and sentenced to several years in prison. The police presence remained heavy in particular blocks to prevent drug selling associated from re-establishing the business. These same tactics were deployed against marijuana selling groups as well, especially after 1995.

Furthermore, local businesses helped develop a Midtown Community Court to more severely sanction the persistent but low-level repeat offenders. This included many low-level marijuana sellers, fare beaters, and sex workers (Erzen, 2001; Kelling & Coles, 1996). Virtually all offenders were found guilty, and if they didn’t have money to pay fines, they were required to perform community service work, attend treatment readiness programs, or some combination of the above. If repeat violators, they were often required to devote up to a week of community service—which interrupted their business dealings. Those not complying with community service sanctions were sent to jail in Rikers Island. Most regular marijuana sellers perceived these sanctions as serious (Golub et al., 2003).

Nuisance Abatement

The NYPD also aggressively used a little known law (NYC Administrative Code 2005, Title 7, Chapter 7) that targeted commercial establishments that permitted flagrant violations of laws and regulations. If the police could document that three or more sales of illegal drugs were made from a particular storefront, they could get a court order that allowed them to padlock (and put out of business) a commercial space for a up to a year or more—thereby depriving drug sellers of their known location and the building business owner of the rental revenue. The implementation of nuisance abatement appeared to have its greatest impact upon the large number of storefronts that were favorite sales outlets for West Indian marijuana sellers throughout low-income communities in NYC (McCabe, 2005). Closing such locations made it somewhat more difficult for marijuana consumers to purchase their drugs—since they could no longer go to a fixed location nearby. Closing these marijuana storefronts also made it somewhat more difficult for low-level street marijuana sellers to obtain wholesale supplies at a moderate cost, which would then be broken into smaller retail sales. Active closure of hundreds of storefronts also removed the appearance that marijuana sales from storefronts was quasi-legal; such closures may have made it somewhat more difficult, or take a consumer more time, to locate and purchase marijuana.

Quality-of-Life Policing

Efforts in the early 1990s to deter and punish persons who were evading payment of subway and bus fares (Kelling & Coles, 1996) was systematically developed into a police strategy designed to combat the perception of widespread disorder in public places—and to restore compliance with civic norms and public order. The overarching policy was referred to as quality-of-life (QOL); the NYPD had a major role for detecting, arresting, and punishing persons who committed a wide range of minor offenses. QOL policing focused on the public and visible, seemingly innocuous (or very minor) offenses like fare evasion, open alcohol containers, public urination, trespassing, marijuana smoking, and about 25 other (noncriminal) violations of the city’s administrative codes (see Golub et al., 2003). Most QOL behaviors are generally victimless (e.g., no complainant would step forward to press charges).

Around 1995, the NYPD decided to stop issuing DATs and C-summonses (with a few exceptions), and instead to arrest and detain persons committing a range of misdemeanors and violations that were defined as QOL behaviors. In the streets and parks of New York City, police officers engaged in a wide variety of proactive crime prevention activities; both police and their critics have labeled these strategies as zero-tolerance policing (Bratton with Knobler, 1998; Eterno, 2001; Maple, 1999; McArdle & Erzen, 2001). Police observation of such QOL violations gives the police probable cause to stop the person, check the individual’s identification, conduct radio checks for outstanding warrants, and search (pat down for guns or drugs) them for contraband or weapons while in the field. If no evidence of criminal activity is found (e.g., no guns, weapons, or illegal drugs), police are also authorized to conduct a radio check of the person’s identity and for outstanding warrents. They may also issue C-summonses for many QOL violations and/or arrest and detain them.

When nothing is found, the citizen is usually released without further processing. In addition, police officers—especially on bike patrols—have become very adept at identifying those smoking marijuana, seizing enough evidence for an arrest, and making arrests for marijuana smoking (possession) and minor sales. These bike patrol officers also stop and/or arrest marijuana “delivery” persons who use bikes to move rapidly around the city. A study found that over 90% of New York arrestees are aware of NYPD policies of arresting for these quality-of-life behaviors (Golub et al., 2003); half report reducing their involvement due to concern about being arrested. In addition, except for being younger, marijuana arrestees have nearly identical characteristics as those arrested for nondrug felony charges.

Changing Police/Court Procedures

The NYPD also developed systematic procedures governing issuance of DATs for QOL offenses. A series of offenses that do not qualify for DATs because of legal or policy restrictions include those prohibited for offenses known as “precinct conditions.” The precinct commander had discretion to determine whether certain offenses were particularly problematic and restrict issuing DATs for violations of these offenses. For example, unlicensed general vending is a problem for the midtown precinct. It is a violation (generally summonsable) in the Administrative Code, but it is rare that a person will get a C-summons for this offense in the midtown precinct. He or she is most likely to be arrested and processed through the system as a “live” arrest. QOL offenses quickly became part of the list of precinct conditions even though they did not appear on the official NYPD list of non-DATable offenses.

Another important consideration for enforcement policies is that NYPD significantly curtailed the issuance of DATs in 1998 after Officer Anthony Massimillo of the 67th Precinct was killed executing an outstanding warrant. His murderer was arrested the week before and was issued a DAT even though he had an outstanding warrant … the very one Massimillo was executing. For some reason, this murderer was allowed to leave police custody with a “disappearance ticket.” After Massimillo’s death, the DAT policy changed; virtually nobody gets a DAT today.

In addition, the District Attorneys’ Offices, the NYPD, and the courts in New York City have worked hard over the years to streamline the arrest processing system. To cut down on costs and time in the system (for both the police and defendants), standardized affidavits were created. Every jurisdiction in the city uses what is known as the Expedited Affidavit Program (EAP). EAP is used for offenses that are “high volume” and contain simple language for preparation. Marijuana offenses are included in the EAP. With the combination of the EAP and no DATs, an officer can process a marijuana arrest in minutes (30-60 minutes). What used to take hours or days can now be done in a fraction of the time. With the official policy of the NYPD encouraging low-level enforcement and easy processing demands, officers are not hampered in making and processing QOL arrests. Indeed, they may enhance their records by making many MPV arrests.

Since 1996, the courts computerized their summons processing function. Now, if a C-summons is received by any criminal court in New York City, it is docketed. If the defendant does not appear on the return date, a warrant is issued for arrest. Even for the most minor encounter like a traffic accident, if a summons is not answered, a warrant is issued. During any subsequent encounter when a radio check is conducted by the police, the person will be arrested and taken to court on the outstanding warrant. Having the New York State criminal identification number (NYSID) and prior arrest information available will also make it possible for the warrant squad to rapidly locate and arrest a person for outstanding warrants.

Arrest, Detention, and Arraignment Process

Almost all QOL violators are now subjected to the entire arrest and detention process. This QOL policy was clearly intended to employ police powers of arrest to enforce compliance with a wide range of regulations, which defined civic norms, and to impose significant sanctions (but short of jail or prison time) upon persons who might violate them. These QOL behaviors included a wide range of morally offensive behaviors occurring in public places, ranging from fare beating (not paying subway/bus fares), trespassing, open alcohol containers, public urination, unlicensed vending, disorderly conduct, gambling, etc.—as well as all marijuana violations.

Under this new QOL policy, police officers were now required to arrest almost all offenders and detain and arraign them—including those contacted for smoking or selling marijuana in public locations. The main consequence of this change in arrest policy was that the vast majority of persons arrested for QOL violations—including arrests for marijuana smoking or selling even small amounts—now spend 16-24 hours6 in detention, and many receive fines.

The arrest process involves suspects being taken into custody, handcuffed, escorted to the precinct house, formally booked for that (often noncriminal or misdemeanor crime) offense, transported to central courts, prior criminal record checked, and held in detention cells for several hours. They then appear before the arraignment court judge. For marijuana offenders, the typical disposition might be dismissal of charges, Adjudication in Consideration of Dismissal (ACOD), a fine of $100-$500, or time served—if the violator had no or minimal criminal history. Marijuana offenders might receive a community service sentence if they had a prior history of previous misdemeanor arrests. For offenders charged with felony possession or sales of large amounts of marijuana, those with prior felony arrests would likely face some jail or prison time or possible referral to a drug treatment program. These punishments are among the most minor and unimportant that judges issue. Moreover, the vast majority of marijuana arrestees have their case dismissed or ACOD, time served, or must pay a fine, so almost all arrestees perceive the punishment as relatively unimportant in their life.7 Persons who sustain an MPV arrest will be entered into the state’s criminal history database (e.g., they provide fingerprints, arrest information, and gain a NYSID number and record). Many MPV arrests are subsequently sealed, and if the person is not subsequently arrested for other criminal offenses, then nothing will happen to him or her in the future. For those with prior arrests or convictions, however, the MPV arrest and disposition will be in their criminal history files.

For the vast majority of marijuana arrestees, the most important sanction and punishment was often the arrest-to-arraignment process. Arrestees usually spent 16-24 hours in police or court custody prior to release—this experience was designed to be quite unpleasant. The food and water was limited and bad; toilets had limited privacy; hard benches provided seating for only about 10 persons, so many needed to sit/sleep on concrete floors. The detention cells were often overcrowded and shared with a wide range of offenders who were often smelly and unkept. Legal representation was limited, and guilty pleas meant the most rapid release.

Although little noted (and official data is never released), important exceptions are made to the policy of “arrest and process every violator” under QOL policing. Persons taken into custody for marijuana violations (and other QOL offenses) may often be issued DATs or C-summonses at the precinct if they meet the four following criteria: (1) they have positive identification and a permanent address, (2) record checks indicate that they are not on a misdemeanor recidivist list (maintained by the department), (3) they have no outstanding warrants (unanswered C-summonses or DATs), and (4) they appear respectful to police and their authority. In addition, marijuana violators under age 16 are processed as delinquents and are released to their parents (NYS Family Court Act, 2005). Persons ages 16 and 17 will likely be arrested and sent to central booking. While avoiding transport to and detention at central booking, persons receiving DATs or C-summonses must subsequently appear at the criminal court and pay any fines levied. Persons receiving such C-summonses are not included (but those with DATs are included) in the arrest statistics presented below.

Marijuana-related violations remain commonplace; persons smoking blunts or joints in public settings are much easier for the typical police officer to locate, stop, and arrest. Officers can maintain their number of arrests and possibly gain some overtime pay as well—although not as much as in previous years.

Trends in Marijuana Arrests in New York City

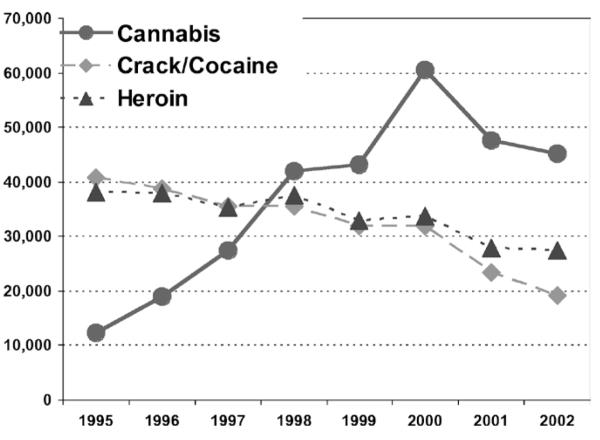

There has been a substantial decline in serious crime (e.g., robbery, homicide, burglary, etc.) in New York City (FBI, 2005). Figure 2 also shows that arrests for heroin in New York City declined from about 38,000 to 28,000, and cocaine/crack arrests declined from 40,000 to 20,000 between 1995 and 2002 (OASAS, 2003). While thousands of persons are arrested and arraigned for minor crimes and violations under the QOL policy, few of these are sent to jail. As a partial result, the average inmate population at the city jails has declined significantly from over 20,000 in 1990 to about 14,000 in 2005 (NYC Department of Corrections, 2005). Nevertheless, marijuana arrests soared in the late 1990s.

Figure 2.

Number of Arrests in New York City by Year and Drug

Source: OASAS, 2003

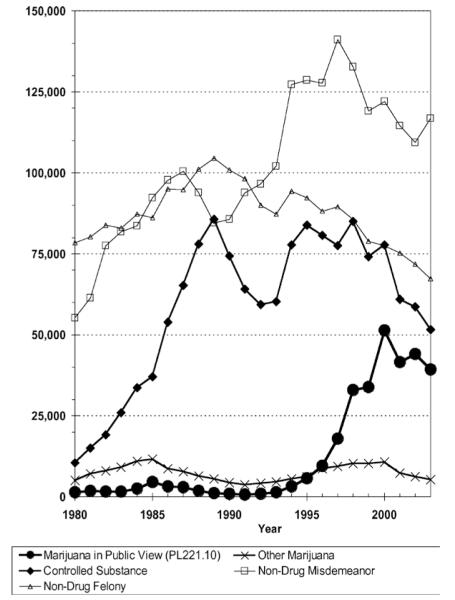

Figure 3 shows important increases in controlled substance (e.g., heroin, cocaine, crack) arrests throughout the 1980s but a substantial decline from 1998 (85,000) to 2003 (52,000). Likewise, a steady decline in nondrug felony arrests occurred between 1989 (105,000) to 2003 (67,000), but QOL enforcement dramatically increased the number of nondrug misdemeanors from 1989 (85,000) to 1997 (141,000) but with steady declines into 2003 (117,000).

Figure 3.

New York City Arrests by Charge Category, 1980-2003

Of most importance to this article is the dramatic rise in MPV arrests. In 1990-1992, under 1,000 arrests occurred, but MPV arrests dramatically increased by 2000 to 51,000 and then exhibited a modest decline by 2003 to 39,000. Note that the number of other marijuana arrests has remained at 10,000 or less per year—so there were no major increases in arrests for marijuana sales in the 1990s when compared with the 1980s. In the early 2000s, marijuana arrests have constituted over 15% of all arrests in New York City and over 40% of all drug-related arrests (data not presented). In the 2000s, 80-90% of the marijuana arrests have been for MPV. Virtually all of the increase has been due to arrests for 221.10 (marijuana smoking) under QOL policing.

The reasons for the declines in marijuana arrests since 2000 are less clear. Some proportion of the decline may also be due to marijuana smokers being more careful to conceal their consumption activity when in public settings or to avoid such settings. Another reason may be modest shifts in the allocation of police resources to security and counterterrorism details. The NYPD management is aware that narcotics and other police officers were targeting the “low hanging fruit,” of which MPV arrests are very common. While the current administration reports seeking to reverse the trend of many MPV arrests, efforts to focus police resources on controlled substance offenders (e.g., heroin, crack, and cocaine) often results in discovery of marijuana smoking or possession.

Impact of Marijuana Enforcement in the 2000s

The proactive policing of marijuana smoking and sales has had a variety of outcomes that cannot be documented with any existing hard data—but it reflects the widespread impressions among thousands of nonmarijuana-using New Yorkers. This includes changes in public behaviors of marijuana users, marijuana sellers, and marijuana markets. It also summarizes the response of city officials and even the anti-marijuana prohibition groups in the city.

The most important outcomes often lack hard data. This is both because police do not keep such data and the phenomenon of interest would generate no (zero) official statistics. That is, to the extent that blunt and marijuana smokers are complying with civic norms and consuming in private locales—making private transfers—these would generate no arrests or “stops” that could be counted. Rather, the following draws upon the authors’ observations of changes in the New York City street drug scene over three decades and cites appropriate publications. The following constitutes a summary of how the effects of enforcing marijuana-related civic norms have influenced marijuana and blunt subcultures. The listing below includes the more important conduct norms followed by blunt and joint users to evade detection by police and/or potential conflict with disapproving nonusers especially in public and quasi-public settings.

Changes Among Marijuana and Blunt Users

Blunt and marijuana users are keenly aware that police are arresting and processing persons for marijuana smoking and possession of joints/blunts (Golub et al., 2003; Golub, Johnson, Taylor et al., 2004). Few users report reducing their marijuana consumption due to the possibility of police contacts; although, they may change the locale of use. Marijuana use rates in the city appear close to or below the national averages and probably haven’t changed greatly in the past decade (ADAM, 2003; Golub et al., 2003; Golub, 2005; Golub, Johnson et al., 2005). They prefer to use in private settings, sessions, and/or at parties (Dunlap et al., 2005; Dunlap, Benoit, Sifaneck, & Johnson, 2006). Probably most blunt/marijuana consumption occurs in private settings. A minority of users limit their blunt or joint consumption only to private settings and so comply entirely with civic norms (Johnson, Ream et al., in press).

On various occasions, most blunt/marijuana users expect to and actually participate in consumption episodes in public or quasi-public settings. They seek out public settings to consume marijuana/blunt that are relatively secluded from or set apart from observation by passersby. They systematically attempt to conceal their marijuana/blunt use in public settings from (nonusing) observers by moving around in public settings, attempting to mask the marijuana smell by using tobacco, integrating their marijuana use among others smoking tobacco, consuming small to moderate amounts of marijuana in a short time period, and scanning the physical environment for police or suspected undercover officers (Johnson, Ream et al., in press). As a major outcome of active enforcement, these concealment efforts by persons using joints and blunts in public settings mean that their public consumption is less visible and observable to the ordinary citizen than was common in New York City in the early 1990s. They appear to passersby to be complying with marijuana-related civic norms—even when not doing so.

Changes Among Marijuana Sellers in Public Settings

Police resources have also targeted marijuana street-level sellers and storefronts for over a decade (McCabe, 2005). The threats of arrest and skillful tactics by police (via bike patrols, undercover officers, buy/bust tactics) have targeted street marijuana sellers and delivery services. These enforcement policies are designed to reinforce the civic norm (no marijuana sales in public locations) and appear to substantially change where and how marijuana is used and sold in New York City. The public policies reviewed above appear to have altered the subculture norms and sales tactics followed by marijuana sellers in 2005, especially in public settings.

Marijuana sellers are highly aware that police are arresting persons for marijuana sales; many have been stopped and/or arrested (probably for possession rather than sales). They maintain a much lower profile in public locations than in the 1980s. They rarely approach or aggressively hawk their wares to unknown passersby. They appear less numerous in public locations than in the 1980s. They rarely sell to someone they do not know. They primarily sell to former customers and/or to those personally referred by regular customers. Many (former) marijuana sellers appear to function as middlemen, buying marijuana for purchasers who do not have connections with a seller. Public transactions are arranged to appear as typical exchanges of pleasantries between the purchaser and seller/middleman. Public transactions may occur in a secluded area that is not too visible to passersby (or to police). Most “storefronts” from which marijuana was routinely sold in the 1980s have been padlocked and closed for good. These stores now sell legitimate products (McCabe, 2005).

The more organized marijuana sellers prefer to develop delivery services and charge minimum delivery prices—which are considerably higher than previously charged by street sellers. Such delivery services are beneficial for both seller and buyer because they make transactions in private locales (usually the purchaser’s home or business) where typical retail transactions are legal. Cell phones and beepers are typically used to make arrangements for purchases. Designer and high-quality marijuana is sold at high prices (around $50 for two grams or more) to selected customers but usually by delivery service (Sifaneck, Johnson, & Dunlap, 2006; Sifaneck, Kaplan et al., 2006). Purchasers may have more difficulty locating marijuana sellers and may have fewer suppliers from which to choose when seeking to purchase marijuana. Locating marijuana sellers in street markets is more difficult; an unknown purchaser will usually have to purchase through a middleperson. Relatively few marijuana sellers operate only from their household, where the purchaser comes to make marijuana purchases.

Changing Perceptions About the “Marijuana Problem” Among City Officials and Citizenry

Compared with drug markets about 1990, the social visibility of illegal drug sales and use (including marijuana and blunts), especially to nondrug using citizenry, has dramatically diminished in New York City. Active drug sellers and users of marijuana/blunts currently follow etiquettes that allow them to remain relatively “invisible” to nonusers (Johnson, Ream et al., in press). Citizens and passersby in the 2000s rarely receive unsolicited “offers” to purchase marijuana or illegal drugs. This large pool of nonusers who remain unaware of marijuana use/sales in public settings means that a political demand for further suppression of marijuana selling appears to be in remission. No clear and identifiable constituency in the city clearly promotes harsher enforcement or targeting of marijuana users. Few public policies are specifically targeted upon marijuana/blunt users or sellers, other than those reviewed above. Other than its responsibilities for enforcing existing laws and order maintenance, the NYPD and mayor’s office does not have a strongly anti-marijuana ideology. Indeed, the current mayor, Michael Bloomberg, admits to enjoying marijuana as a young adult (“You Bet,” 2002), but his administration has consistently supported QOL enforcement against marijuana smokers and sellers and proclaims substantial success in reducing both serious crime and minor offending (“Quality of Life,” 2001; “Mayor to Keep,” 2006). On an ideological level, marijuana enforcement is as (un)important and is often equated with farebeating, drinking alcohol in public, disorderly conduct, trespassing, and other QOL behaviors.

The mayor, good government elites, and many other constituencies appear satisfied that current city policies are “doing well enough” in the fight against crime. Marijuana use/sales indicators (of arrest and prevalence) are only one of the many crime indicators that “look good” and are “going down.” Officials appear to interpret this data as meaning that the marijuana use/sales can remain a low priority for city officials (even though the absolute number of marijuana arrests remains high).

Limited Opposition to Marijuana Enforcement Policies

New York City is also a central location of persons and organizations that help finance and provide intellectual leadership for the anti-marijuana prohibition in America. A Hedge Fund financier, George Soros, provides substantial funding for organizations that oppose marijuana prohibition. He largely funds the Drug Policy Alliance (led by Ethan Nadelmann) and helps support other pro-marijuana organizations in New York City and elsewhere. This leadership and funding has sponsored many referendums for medical marijuana and legislative reform, mainly in western states but also in New England. Significantly, these groups have not focused upon advocacy for medical marijuana in New York State, nor have they been successful in challenging or changing the city’s police enforcement policy.

In a political sense, opposition to police enforcement policies has rarely focused upon marijuana arrest policies. Political leaders from the large and politically influential African-American and Hispanic communities have been united and vigorously opposed to what they consider to be zero tolerance policing and court outcomes that result in racial profiling and ethnic disparities in arrests, court processing, and especially incarceration (McArdle & Erzen, 2001). This includes police tactics of stopping, questioning, and possibly searching persons for guns, knives, and drugs in the streets; police disproportionately stopping African-American drivers and youths, and sentencing policies that incarcerate hundreds of minor actors in the drug trade for lengthy prison sentences. Yet, these minority political leaders have not specifically objected to police enforcement directed against marijuana smokers even though a majority of MPV arrestees are minorities (as is the case for other crimes).

Likewise, potential constituencies of white and middle class marijuana users may quietly oppose tough marijuana enforcement policies, but very few are active politically in efforts to change laws or enforcement policies in New York State. These pro-marijuana (anti-prohibition) user and policy groups have been unable to mobilize politically to bring about changes in marijuana legislation and/or change in enforcement practices in New York City. While a sizable number of marijuana/blunt users organize a “legalize marijuana” rally every May Day. In recent years, they must obtain city permits to march down Broadway to Battery Park. Organizers agree not promote the use of marijuana at the event; the number of participants has dwindled in the 2000s.

Conclusions

The changes in policing appear to have largely succeeded in bringing about routine compliance with the civic norms of no marijuana smoking or sales in public places, but it took almost a decade of sustained enforcement to bring about such compliance. By 1999, the vast majority of arrestees were aware that police were targeting marijuana smoking and street sellers for arrest and punishment, and half of those involved indicated reducing their involvement (Golub et al., 2003). Even among marijuana users claiming no arrests, virtually all are aware that police are searching for and arresting persons for marijuana smoking, possession, and sales. Regardless of gender, ethnicity, and age, most marijuana users report following etiquettes that limit their marijuana consumption to private locales or taking steps to evade detection by police (Johnson, Ream et al., in press). In the 2000s, consumers appear more careful to conceal their marijuana smoking in public settings from passersby and police (Dunlap et al., 2005; Sifaneck et al., 2005).

Marijuana sellers are much less visible in public settings. Sellers no longer approach or aggressively sell their product to passersby and citizens—as was common in the 1980s. Many sellers may function as middlepersons between buyers and sellers. Marijuana delivery services are much more common. Even when they are present in public locations, marijuana sellers and delivery persons seek to blend into conventional activities and appear to be complying with the civic norms—even when they are engaging in transactions.

While the policing and enforcement activities delineated above appear to have restored compliance with civic norms of no marijuana use or sales in public locales (as perceived by institutional elites), the focus of this article has neglected important drawbacks associated with such policing policies. Other articles (Golub, Johnson, & Dunlap, 2006, in press) will document important ethnic disparities in the role of marijuana arrests and dispositions. Large numbers of marijuana smokers arrested on MPV charges have accumulated first (and possibly subsequent) arrests that are now included in the state criminal history files—they have NYSID numbers and fingerprints stored in electronic files. Although most MPV cases are probably sealed, those who are subsequently arrested for other minor charges or felony crimes will be more easily identified and begin building a criminal record.

The perceived success of QOL policing towards marijuana users/sellers in public settings and the absence of an organized opposition targeting police policies of arresting large numbers only for MPV in public settings has become well institutionalized in New York City. Continuity in the current marijuana policy for the remainder of the 2000s is most likely, given the current popularity of QOL policing, citizen satisfaction with low crime rates, and a lack of concern or organized opposition about the drawbacks of these policies. Such changes would likely require marijuana users to maintain relative compliance with civic norms but reducing the harms and potential harms of gaining a criminal record among those contacted or arrested by police. Any future changes in marijuana policy and its enforcement would need better information about the pros and cons of such enforcement and more sustained opposition to current policies by the city’s many blunt and marijuana users.

Acknowledgements

This analysis was primarily supported by funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, “Marijuana/Blunts: Use, Subcultures and Markets” (1R01 DA/CA13690-05), and by other NIDA projects (R01 DA021783, R01 DA009056, T32 DA007233), and the Marijuana Policy Project. Points of view and opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the positions of the funding agencies or sponsoring institutions. The authors acknowledge with appreciation the many contributions to this research of Ellen Benoit, Ricardo Bracho, Flutura Bardhi, Anthony Nguyen, and Doris Randolph.

Biography

Bruce D. Johnson, PhD, is one of the nation’s authorities on the criminality and illicit sales of drugs in the street economy and among arrestees and minority populations. He directs the Institute for Special Populations Research at the National Development and Research Institutes. He is a professional researcher with five books and over 130 articles based upon findings emerging from over 30 different research and prevention projects funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and National Institutes of Justice. He also directs the nation’s largest pre- and postdoctoral training program in the United States.

Andrew Golub, PhD, is a principal investigator at National Development and Research Institutes, Inc. and at the University of Vermont. His research focuses upon understanding drug use trends in context and often involves the integration of quantitative and qualitative research methods. He also integrates information from multiple complex data sets and conducts secondary analyses of national data sets. He has authored over 40 publications in peer-reviewed journals.

Eloise Dunlap, PhD, has extensive qualitative experience in research and publications that address the role of crack users, crack dealers, and drug-abusing African-American families, and their households. She has been the principal investigator of six NIDA-funded projects. Her current projects include Transient Domesticity and Violence in Distressed Households; Marijuana/Blunts: Use, Subcultures and Markets; and Disruption and Reformulation of Illicit Drug Markets Among New Orleans Evacuees.

Stephen J. Sifaneck, PhD, is presently a project director/co-investigator in the Institute for Special Populations Research (IPSR) at NDRI. His publications include articles and chapters about the sale and use of marijuana, heroin, and prescription drugs; ethnographic research methodologies; and subculture and urban issues.

James E. McCabe, PhD, is an assistant professor of criminal justice at Sacred Heart University. He is also a 21-year veteran of the NYC Police Department. During his NYPD career, he held numerous assignments. For two years (2001-2003), he was the commanding officer of the NYPD Police Academy and Training Bureau. His research interests include police organizational behavior and how the dynamics of drug and quality-of-life enforcement affect crime levels and community safety.

Appendix: Definitions and Criminal Justice Processing of Marijuana Arrests Followed by New York City Police Department, 1995-present

Developed in conjunction with James McCabe, PhD, Department of Criminal Justice from John Jay College of City University of New York, 2004. Although the following definitions are little known by civilians, most of the definitions and procedures are covered during police academy training (and more details are provided in the NYPD Patrol Guide § 208-227).

The focus is upon Marijuana Possession in the 5th Degree (221.10), which is abbreviated MPV—and is a B Misdemeanor in New York State Law. MPV is by far the most common arrest charge that is marijuana-related and typically involves a person arrested for smoking a joint or blunt in a public location. The criminal justice definitions and processes described below are equally applicable to a wide range of other misdemeanors and noncriminal code violations that are now being enforced as part of quality-of-life policing.

There is a substantial legal difference between a DAT and Summons, as explained below.

-

1. What is a desk appearance ticket [DAT]? (New York State Criminal Procedure Law §150.20)

This involves a criminal charge (for example, a marijuana smoking arrest 221.10) but may also be issued for many other misdemeanor arrests. The arrestee receiving a DAT is released at the precinct but must report for criminal court arraignment about a month later. A DAT is given in place of going through the whole criminal justice detention and arraignment process (described below). For example, a person is caught smoking a blunt or joint (221.10). The arresting officer then takes the person into custody and seizes the evidence. The person is arrested and handcuffed in the street; the arresting officer takes the person to the precinct. He or she is handprinted and fingerprinted at the precinct; the arrest information is entered via the precinct arrest booking procedure (e.g., computerized entry of data into the NYPD online booking system). This generates an arrest number and the beginning of a NYSID8 number (if none exist at the present time). At the precinct, the person is checked for prior arrests and outstanding warrants, and his or her identity is verified (via photo ID, driver’s license, address checked). If the information is accurate (and no warrants), the police may issue a DAT (but its issuance is optional for the precinct officials—but see 4. below). If given a DAT, the arrestee is given a written ticket (DAT) and released at the precinct; the DAT requires him or her to show up at the same arraignment court (as detained persons) about a month later; the case is arraigned and usually disposed at that time. For marijuana-related charges, DATs may be given if the arrestee has extenuating circumstances, such as care for children at home, going out of town the next day, or some similar extenuating situation. NYPD policy holds that all persons arrested for selling marijuana (even a joint or small amount) are to be arrested and detained—none should receive a DAT. If age 16 or older, the person goes through the detention/arraignment process described below.

Note: If violators are age 15 and younger, they don’t get arrested, but the officer takes them into custody and brings them to the station house, where they are usually released to parents or guardians (NYS Family Court Act Article 7, Part 1, §712, NYPD Patrol Guide 215-08).

The arresting officer must also file an affidavit (the official criminal complaint), which lists the particulars of the arrest. The officer now fills out the affidavit via the Expedited Arrest Program (this is not for all DATs, but does apply to MPV, except on Staten Island). This is a preprinted affidavit (now done on a computer terminal at the precinct), in which the officer checks off standard complaint language and submits any evidence (e.g., remnants of a joint or blunt or amounts of marijuana seized). These are sent down to the court and matched with the arrest charge when the recipient of the DAT appears in court.

What happens if the violator does not show at arraignment? The judge would then issue an arrest warrant for failure to appear in court. Failure to appear has a greater penalty than most marijuana charges. This would also be enforced by the NYPD warrant squad and likely result in an arrest, detention for up to 24 hours, and imposition a more severe penalty.

-

2. What is a summons? These are very minor criminal acts and the least serious penal law violations. They are also issued due to violations of other types (non-criminal) of city and state regulatory codes. Police have responsibility for handling them, making arrests, and issuing summonses (tickets). Some persons arrested for noncriminal acts go through the arraignment process described below (due to lack of identification or current warrants). (NYS PL 2005. 100.10, NYPD Patrol Guide 209-01).

There are four major kinds of Summonses: (1) Parking ticket, (2) Moving traffic violation, (3) Criminal court summons, and (4) Environmental Control Board [ECB] violations (noise, dog waste, littering, fare evasion, trespassing). The main focus here is upon the C-summonses (referrals to criminal courts). They involve penal law violations (such as 221.05). Public drinking, urination, littering, disorderly conduct, street sales of tobacco products, and trespassing are eligible for C-summonses—many are now treated as QOLs. For some offenses, the arresting officer can issue either a C-summons or ECB summons; the type of summons effectively changes the venue (court) where it will be adjudicated.

If the person has proper identification in the street, the officer conducts a name check for warrants via radio communication. If there are no warrants, ID check is confirmed, the C-summons will be written by the officer, and the violator is released on the street—no handcuffs, arrests, or precinct visit. The C-summons requires the offender to report (about a month later) to the same criminal arraignment court as all other criminal arrestees (both those detained and answering DATs) where the case will be adjudicated. When the person with a C-summons appears in court, the only disposition for a judge is to dismiss the case or impose a fine (for the violation). While a judge may impose jail and probation for C-summonses, this happens very rarely, if ever, but the sanction is in the judge’s power. Other dispositions below are not imposed (e.g., no ACOD, no time served).

The following constitute strategic policies that the NYPD has implemented as standard procedures for a decade (from about 1996 to the present).

-

3. Persons who lack verifiable identification or have a criminal justice status or outstanding warrants will always be sent to criminal court arraignment (see 4).

If an arrestee or a person receiving a C-summons does not produce good identification (e.g., usually a driver’s license, credit cards, or passport, or other verifiable ID), or radio checks cannot verify the identification of that person, he or she is held and sent to criminal court (see 4 below). If a person is wanted for another offense or has an outstanding warrant (even for a minor violation years ago), he or she is to be detained and arraigned. (Note: A person who may have a prior criminal record, but the sanction(s) have expired a year or more previously, may be eligible to receive a DAT or C Summons. But depending upon the nature of the prior and current charge, such persons may be detained and arraigned.)

-

4. Persons transferred for detention and central arraignment. Every arrestee who does not receive a DAT and is not issued a C-summons will be escorted from the local precinct to the central criminal court for detention and arraignment.

New York City has 76 different precincts; each borough has its own central criminal courts—which operate all the time (except on Staten Island). Typically, each precinct has “holding cells” where several arrestees are held. A police transport vehicle (often called a “paddy wagon”) goes to each precinct. The handcuffed arrestees are often chained together, put in the paddy wagon, and taken to each borough’s central criminal court for arraignment. At entry, digital photos are taken and linked to each arrestee. This information is transmitted electronically to the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services (DCJS) where the fingerprints and/or photos are carefully compared to verify whether the individual has a prior criminal history and NYSID number; in some cases, DCJS may also check FBI records for out-of-state arrests, dispositions, and warrants. Since most arrestees (about 80-90%) have an existing NYSID number, the courts send back the criminal history record (often called a “rap sheet”) for each person; this contains their prior arrests, convictions, sentences, and incarcerations. It often takes DCJS 4-12 hours to do this fingerprint check and return the rap sheet to the court. During this interval, all persons are held in large “detention cells” with many other offenders arrested on a wide range of charges. The typical time in detention cells is 6 to 24 hours, but some offenders may be held longer if record checking by DCJS takes several hours.

-

5. Appearance at criminal court arraignment.

When the rap sheet is available and other court procedures are completed, the offender is taken to court where he or she appears before the arraignment court judge. For most misdemeanor arrestees (especially for MPV) and all C-summons cases who have been detained, this will be their only court appearance. In addition, the docket at this arraignment court will also include persons who have received DATs or C-summonses (issued about a month previously). Both prosecution and defense attorneys will strongly encourage the offender to accept a plea bargain that will typically result in release following their arraignment. In most cases, the judge will impose a disposition that reflects the “going rate” for that offense in the court. The more severe dispositions (extra jail time or fine plus probation) will typically be imposed on MPV arrestees who have relatively more extensive criminal histories.

-

Dispositions for MPV and C-summonses

The arraignment court judge has a limited range of dispositions that can be imposed. The dispositions are the same for persons reporting to court with a DAT or a C-summons as for those held in detention. (Sealing and expunging of the offender record are explained later.) All dispositions for Penal Law offenses can be found in Section 60.01 of the NYS PL. These dispositions include the following:

Dismissal: (NYS CPL. 2005. 170.30) The judge effectively vacates or eliminates the arrest charge. This disposition mainly occurs when police or court paperwork is not completed (e.g., an affidavit is not available), improper procedure by police, no evidence is available that the suspect was using marijuana or possessed it (person arrested with several others who were using it); or the seized material did not test positive for marijuana. All dismissed cases are sealed.

Adjournment in Consideration of Dismissal (ACOD) (CPL 2005. 170.55; CPL 170.56 is especially for MPV, and PL 65.05). MPV ACOD is covered under Section 170.56 of the CPL and may be up to a year, but is usually 6 months. The judge makes no adjudication at the initial arraignment and tells the offender that if he or she is not rearrested within a given time period (usually 6 months), this charge will be automatically dismissed (and the offender will not have to return to court). If an ACOD is given, the case is automatically docketed for the date in question. If there is no subsequent arrest of the offender, the case is dismissed, and the rules in a. apply. If an MPV arrestee received an ACOD disposition at arraignment, it would be sealed—especially if this is a first offense. While the person has acquired an NYSID number, this event will be sealed by DCJS computers after 6 months if there are no subsequent arrests. If the offender has a prior NYSID and a prior felony arrest or misdemeanor conviction, the ACOD disposition will be recorded and remain on the permanent record. Sealing records is still permissible but uncommon for a person with a moderate to extensive criminal history.

Time Served: (PL 2005. 60.01) The person is convicted of the charge but released after arraignment. The judge determines that the duration of detention (typically about 24 hours) constitutes sufficient punishment for this offense. But this constitutes a conviction to the charge that remains on the person’s criminal history record (and is not sealed).

Fine: (PL 2005. Article 80, CPL 420.05) The judge convicts the offender of an offense and imposes a monetary fine. Penal Law Article 80.05 (2) indicates the maximum fine for an MPV offense is $500, but $100 is common and the range varies. This constitutes a conviction that remains in the criminal history record and does not get sealed.

Probation: (PL 2005. 65.00) Some MPV offenders, especially with prior records, may be convicted, given a fine, and placed on probation for a period of time (possibly up to a year, but usually less). Few MPV offenders get only probation (without a fine). This constitutes a conviction that remains in the criminal history record and does not get sealed.

Additional Jail Sentence: (PL 2005. 60.01) The MPV offender is sentenced to Rikers Island for a short time (2-3 days is typical) but may last for up to a year. This is in addition to what the offender has already served in detention. This constitutes a conviction that remains in the criminal history record and does not get sealed.

-

7. Expunging and Sealing of Criminal History Records.

New York State law provides for two mechanisms by which a person’s actual contacts with the criminal justice system can be eliminated or significantly hidden in future criminal justice contacts.

Expunging: Involves the deletion of any information about the offender or the offense from the DCJS criminal history database. Any future computerized search for that individual will not find any electronic record present. Expunging is relatively rare. Typically, it occurs when a person has violated a noncriminal regulation (such as unlicensed vending, selling tobacco products, or alcohol violations in public); such violators would typically receive a C-summons and be released—but need to appear in criminal court for disposition. But officers stopping persons for C-summons offenses without adequate ID will arrested and detained through arraignment. While the judge will likely order them to pay a fine, they will not be convicted of a criminal code offense (and hence do not belong on the state’s criminal history files). If they have no prior criminal arrests or convictions, their contacts through the detention and arraignment process (e.g., the arrest record, affidavit, photos, fingerprints, initial NYSID number) will be expunged (e.g., deleted from the computer database maintained by DCJS). (Note: The record of their C-summons and the fine imposed may remain in other noncriminal databases maintained by the courts and judicial system).

Sealing: This involves the retention of almost all arrests and dispositions in the DCJS electronic database. But specific arrests and dispositions are coded as sealed—this means that a given arrest/disposition is suppressed (and not present) in future criminal justice searches about that offender. A future printed “rap sheet” will not list that offense, nor will a police radio check reveal that prior record. Suppose that a first time MPV arrestee in January 2003 is given an ACOD disposition; six months later (and with no subsequent arrests of that person), the DCJS database will automatically seal it, and the disposition of that arrest charge will be recorded as both ACOD and “dismissed” on the DCJS database. If the same person is arrested two years later in July 2005, the rap sheet obtained by the court will report no prior criminal history for that person. A variety of different statutes and practices govern the sealing of criminal history events and records; these are little understood by citizens and even most law enforcement officers—but are implemented by those maintaining the DCJS database. Sealing is more widespread than is realized; nearly one-third of the total volume of arrest events in New York State are coded as sealed (Golub, 2006).

Expunging and sealing are typically associated with the first or second arrests but happen less often as the person has more arrests with the criminal justice system.

Once a person acquires a NYSID number and has photos and fingerprints in the database (that are not expunged) and gains a criminal conviction (fine, time served, probation, jail), subsequent arrests for minor offenses (like MPV) that are ACOD or dismissed are routinely not sealed. These arrest events (but favorable dispositions) will be provided on rap sheets during subsequent arrests or radio checks.

Endnotes

Arrestees in Manhattan and New York City have consistently had among the highest proportions of heroin and cocaine/crack users among the 35 major cities that participated in the Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring program (ADAM, 2003).

Since marijuana possession and sales were charged under the same criminal statutes as heroin and cocaine, the number of charges for marijuana cannot be disaggregated for this period. Police had considerable discretion to seize/discard marijuana and not officially arrest persons they caught with small amounts of marijuana during this period.

Indeed, a majority of American states list marijuana as a controlled substance and may punish violators with jail/prison terms.

Such police “raids” into private property remain common, however, for modest amounts of crack, cocaine, and heroin—when police have reasonable suspicion or court order to enter such private locations. Police raid marijuana growers and midlevel distributors when they can identify such key persons.

This administration also instituted a variety of police activities, interagency collaborations, and private resources to enforce compliance with their version of civic norms—including controlling sidewalk vending, payment of transit fares, restoration of parks, gentrification of poor communities, traffic enforcement, etc.—that are beyond the scope of this article.

Despite a court order agreeing to a 24-hour window between arrest and arraignment, the New York Times (2/2/2006) reports that nearly one-third of arrestees spend more than 24 hours in detention before arraignment.

A forthcoming report (Golub, Johnson, & Dunlap, in press) will systematically document trends in arrest charges, dispositions, and ethnic disparities among marijuana-related arrests in New York City during 1980-2003. See the Appendix for definitions of these dispositions.