Abstract

Deregulations of microRNA have been frequently observed in tongue squamous cell carcinoma (TSCC), but their roles in tumorigenesis are not entirely clear. Here, we reported the up-regulation of miR-24 in TSCC. MiR-24 up-regulation reduced the expression of RNA-binding protein dead end 1 (DND1). Knockdown of miR-24 led to enhanced expression of DND1. The direct targeting of miR-24 to the DND1 mRNA was predicted bioinformatically and confirmed by luciferase reporter gene assays. Furthermore, the miR-24-mediated change in DND1 expression suppressed the expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (CDKN1B), and also led to enhanced proliferation and reduced apoptosis in TSCC cells.

Keywords: microRNA, miR-24, DND1, CDKN1B, proliferation, TSCC

1. Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is an undertreated and understudied disease. According to the American Cancer Society [1, 2], while overall new cancer cases increased about 8% during the past 5 years, the new cases for OSCC increased by about 21%, and the new cases for OSCC of the tongue (TSCC, the most frequent type of OSCC) increased by over 37% in the same period. More strikingly, while the number of death associated with all cancers decreased, the number of death associated with OSCC increased by 4%, and the number of death associated with TSCC increased by over 10% during the past 5 years. These statistics indicate a major health problem, and point to the immediate need for a better understanding of this disease. While attempts have been made to identify genomic alterations that contribute to the initiation and progression of TSCC, most efforts are focused on protein coding genes. Our knowledge of genomic aberrations associated with non-coding genes (e.g., microRNA) and their contributions to the onset and propagation of TSCC is relatively limited.

MicroRNAs are a class of small non-coding RNAs of approximately 22 nucleotides in length that are endogenously expressed in mammalian cells. They regulate the target gene expression at the post-transcriptional level by repressing translation and/or facilitating mRNA degradation. MicroRNAs are essential regulators of a range of cellular processes including proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, survival, motility and morphogenesis. Several microRNAs have been functionally classified as proto-oncogenes or tumor suppressors [3], and are aberrantly expressed in different cancer types, including OSCC [4-7].

Up-regulation of miR-24 has been observed in a number of cancers [8, 9], including OSCC [10]. The up-regulation of miR-24 appears to be associated with the progression of OSCC [10]. Our study confirmed the up-regulation of miR-24 in TSCC, one of the most common subtypes of OSCC. We further demonstrated that miR-24 expresses its effects in part through targeting RNA-binding protein DND1, which in turn post-transcriptionally regulates its downstream genes, including cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (CDKN1B).

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Tumor procurement and RNA extraction

TSCC tissue samples and the adjacent normal tissues were obtained from 6 TSCC patients. The demographics of the patients were as follows: 4 male, 2 female; mean age of 52.3 years; there were two T1 cases, three T2 cases and one T3 case. This study was approved by Institutional Review Boards. Tissue samples were obtained after the tumor resection and snap frozen. Specimens containing more than 85% tumor cells on H&E pathological examination were selectively microdissected. The total RNA was isolated using miRNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen), and quantified by the RiboGreen RNA Quantitation Reagent (Molecular Probes).

2.2 Cell culture and transfection

The TSCC cell lines (UM1, UM2, Cal27, SCC4, SCC1, SCC2, SCC9, SCC15, and SCC25) and immortalized NOK16B cell line used in this study were maintained in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (GIBCO) at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2. Primary normal human oral keratinocytes (NHOK) were prepared and cultured in OKM medium (ScienCell Research Laboratory) as previously described [11]. For functional analysis, the following reagents were transfected into cells using DharmaFECT Transfection Reagent 1 as previously described [12]: miR-24 mimics and non-targeting miRNA mimics (Dharmacon), locked nucleic acid knockdown probe specific to miR-24 (anti-miR-24 LNA) and negative control LNA (Exiqon), and gene specific siRNAs to DND1, CDKN1B and control non-targeting siRNA (On-TargetPlus SMARTpool, Dharmacon).

2.3 Quantitative RT-PCR analysis

The relative expression levels of miR-24 were determined using GenoExplorer microRNA quantitative RT-PCR kit (GenoSensor Crop.) as described previously [12]. The relative expression level was computed using the 2-delta delta Ct analysis method [13], where U6 was used as an internal reference.

2.4 MicroRNA target prediction

The candidate targets of miR-24 were identified based on a conservative intersection of 3 common microRNA target prediction tools: TargetScanHuman 5.1 [14], PicTar [15] and miRBase [16]. For our study, genes that were predicted by at least 2 of the methods were defined as high confidence candidate targets of miR-24.

2.5 Western Blotting Analysis

Western blots were performed as previously described [17] using antibodies specific to DND1 (Sigma), CDKN2A (Cell Signaling), CDKN1B (BD Biosciences) and beta-actin (Sigma). For semi-quantification, the western blot bands were quantified using a ChemiDoc XRS System (Bio-Rad) equipped with Quantity One software (version 4.6.3). The relative DND1 levels were expressed as DND1/actin.

2.6 Dual luciferase reporter assay

A 65-bp fragment from the 3’ untranslated region (3’-UTR) of DND1 (position 1442 to 1506, NM_194249) containing the predicted miR-24 binding site was cloned into the Xba I site of the pGL3 firefly luciferase reporter vector (Promega). The corresponding mutant construct was created by mutating the seed region of the miR-24 binding site. Using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), cells were transfected with the reporter contructs containing either the targeting sequence from the DND1 3’-UTR (named pGL-DND1) or its mutant (named pGL-DND1m). The pRL-TK vector (Promega) was co-transfected as control for transfection efficiency. The luciferase activities were then determined as previously described [17] using a Lumat LB 9507 Luminometer (Berthold Technologies).

2.7 Proliferation and apoptosis assay

Cell proliferation was measured by MTT assay as previously described [18], with minor modification. In brief, 48 hrs post transfection, medium in each well was replaced by 100 μl of fresh serum-free medium with 0.5g/L MTT. After incubation at 37 °C for 4 hrs, the MTT medium was aspirated out and 50 μl of DMSO was added to each well. After incubation at 37 °C for another 10 min, the absorbance value of each well was measured using a plate reader at a wavelength of 540nm. The apoptosis was measured using the Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (Invitrogen) and meastured with a flow cytometer (FACScalibur, Becton-Dickinson) as previously described [12].

2.8 Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. The differences between groups were determined by Student’s t-test (two-tailed). Differences were declared significant at p < 0.05 level. Correlations were assessed using Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient.

3. Results

3.1. Up-regulation of miR-24 in TSCC

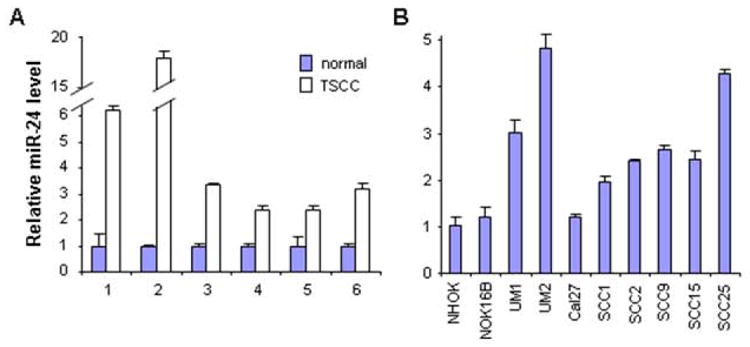

As shown in Figure 1A, enhanced miR-24 levels were observed in TSCC tissue samples as compared to the normal tissue samples from the same patients. Enhanced miR-24 levels were also observed in 7 out of the 8 TSCC cell lines as compared to the non-tumorgenic cells (NOK16B and NHOK) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Enhanced miR-24 level in TSCC.

The qRT-PCR was performed to assess the miR-24 level in: (A) TSCC and their normal control tissue samples, and (B) a panel of TSCC cell lines, and an immortalized non-tumorgenic cell lines (NOK16B), and normal oral keratinocyte cell culture (NHOK). Statistically significant increases in miR-24 levels were observed for the paired tissue samples (p < 0.05). For the TSCC cell lines tested, up-regulation in miR-24 levels were observed in 7 of the 8 TSCC cell lines when compared to NHOK or NOK16B (p < 0.05).

3.2. Bioinformatics analysis of miR-24 targets

To further explore the functional roles of miR-24 in TSCC, a bioinformatics-analysis was carried out to identify the potential targets for miR-24 as described in Materials and Methods. A total of 102 candidate targets for miR-24 were identified (predicted by at least 2 methods, Supplementary Table 1). Among those predicted targets, the dead end 1 (DND1) gene encodes for a RNA-binding protein that is involved in nucleic acid editing [19] and regulation of mRNA stability [20]. The reverse target prediction analysis indicated that there are potentially 4 microRNAs that target DND1, including miR-24, miR-370, miR-634, and miR-889 (predicted by at least 2 methods, Supplementary Table 2). While up-regulation of miR-24 has been shown in TSCC, the levels of miR-634 and miR-889 were undetectable in our samples, and miR-370 was not differentially expressed in TSCC (data not shown). The bioinformatics analyses led us to investigate the functional relevance of the miR-24 effect on DND1 in TSCC cells.

3.3 DND1 is a direct target of miR-24

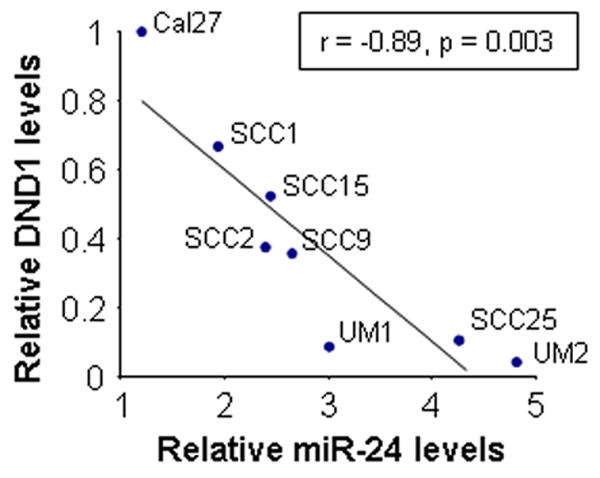

As shown in Figure 2, the levels of miR-24 and DND1 were inversely correlated in TSCC cell lines (Pearson’s correlation coefficient = -0.89, p = 0.003, Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 2. Correlation of miR-24 and DND1 levels in TSCC.

The levels of miR-24 and DND1 were determined in TSCC cell lines based on quantitative RT-PCR and Western blot, respectively. A reverse correlation between miR-24 and DND1 levels was observed (Pearson’s correlation coefficient = -0.89, p = 0.003).

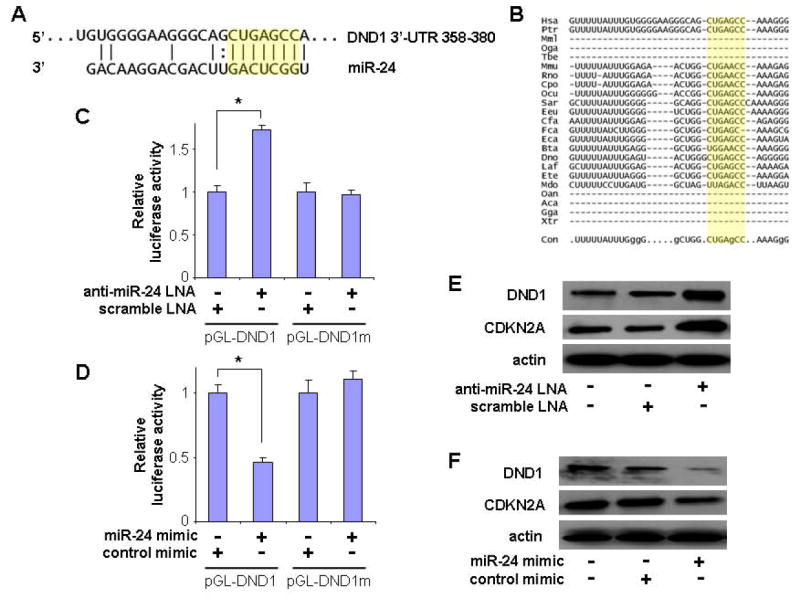

Based on the bioinformatics analysis, a highly-conserved miR-24 targeting sequence was identified in the 3’-untranslated region of DND1 mRNA (Figure 3A & B). To confirm that miR-24 directly targets this sequence, dual luciferase reporter assays were performed using the construct in which this targeting site was cloned into the 3’-UTR of the reporter gene (pGL-DND1). As illustrated in Figure 3C, when cells were treated with anti-miR-24 LNA, the luciferase activities were significantly enhanced as compared to the cells treated with scrambled LNA. When cells were transfected with miR-24 mimic, the luciferase activities were significantly reduced as compared to the cells transfected with negative control (Figure 3D). When the seed region of the targeting site was mutated (pGL-DND1m), the miR-24 effects on the luciferase activity were abolished. Furthermore, as shown by Western blot (Figure 3E), knockdown of miR-24 using anti-miR-24 LNA increased the protein level of DND1 in UM2 cells. Similarly, CDKN2A, a known target of miR-24 [21], was also up-regulated by anti-miR-24 LNA treatment. In contrast, ectopic transfection of miR-24 reduced the protein levels of both DND1 and CDKN2A in UM2 cells (Figure 3F). Similar results were observed in UM1 cells and HeLa cells (data not shown).

Figure 3. MiR-24 direct targeting DND1 mRNA.

(A) The predicted miR-24 targeting sequence located in the 3’-untranslated region (3’-UTR) of DND1 mRNA. The seed region is highlighted in yellow. (B) The alignment of the miR-24 targeting sequences located in the 3’-UTR of the DND1 genes from 23 organisms. The evolutionarily conserved nucleotides are indicated with capital letters in the sequence shown on the bottom. Dual luciferase reporter assays were performed as described in the Materials and Methods section on cells transfected with constructs containing the predicted targeting sequence (pGL-DND1) or mutated targeting sequence (pGL-DND1m) cloned into the 3’-UTR of the reporter gene, and treated with anti-miR-24 LNA or scramble LNA (C), or treated with miR-24 mimic or control mimic (D). * indicates p < 0.05. Western blot analyses were performed to examine the effects of miR-24 on DND1 expression in UM2 cells that were treated with anti-miR-24 LNA or scramble LNA (E), or on cells that were treated with miR-24 mimic or control mimic (F). The expression of CDKN2A, a known target of miR-24 [21], was also examined in these cells. Data represents at least 3 independent experiments with similar results.

3.4 MiR-24-mediated down-regulation of DND1 reduces the CDKN1B expression, and regulates proliferation and apoptosis in TSCC cells

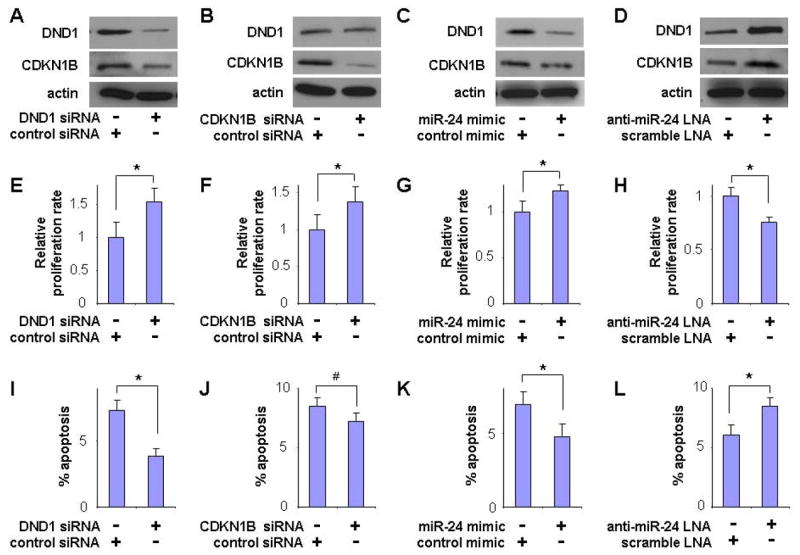

It has been shown previously that the expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (CDKN1B) is up-regulated by DND1 at the post-transcriptional level [20]. Here, we demonstrated that knock-down of DND1 by siRNA led to reduced expression of CDKN1B in TSCC cells (Figure 4A). This DND1 knockdown-mediated down-regulation of CDKN1B was accompanied by enhanced proliferation (Figure 4E) and reduced apoptosis (Figure 4I). Similar effects on proliferation and apoptosis were also observed when cells were treated with siRNA specific to CDKN1B (Figure 4F and 4J). The miR-24-mediated down-regulation of DND1 also resulted in reduced CDKN1B expression (Figure 4C), which was accompanied by enhanced proliferation (Figure 4G) and reduced apoptosis (Figure 4K). In contrast, knockdown of miR-24 by anti-miR24 LNA treatment resulted in enhanced DND1 expression, which led to enhanced CDKN1B expression (Figure 4D). This was associated with a concomitant reduction in cell proliferation (Figure 4H) and increased apoptosis (Figure 4L).

Figure 4. The effect of miR-24 on DND1 and CDKN1B expression and cell growth.

The UM2 cells were treated with DND1 specific siRNA or control siRNA (A, E, I), CDKN1B specific siRNA or control siRNA (B, F, J), miR-24 mimic or control mimic (C, G, K), and anti-miR-24 LNA or scramble LNA (D, H, L). Western blot were performed on these cells to examine the expression of DND1 and CDKN1B genes (A-D). Proliferation (E-H) and apoptosis (I-L) were also measured in these cells. Data represents at least 3 independent experiments with similar results. * indicates p < 0.05, and# indicates p < 0.1.

4. Discussion

In this study, we reported the up-regulation of miR-24 in TSCC. This finding is in agreement with the recent observation that miR-24 is up-regulated in OSCC and contributes to the growth of OSCC cells in vitro [10]. In addition, up-regulation of miR-24 has also been observed in gastric and cervical cancers [8, 9]. However, its role in tumorigenesis is not entirely clear.

To understand the role(s) of microRNA in complex systems (i.e., TSCC), it is important to identify the functional modules involved in complex interactions between microRNA and their targets (e.g., mRNA). In our study, by combining 3 commonly used microRNA target prediction methods (PicTar, TargetScanand and miRanda), a number of important candidate targets for miR-24 were predicted. Among these potential targets, DND1 is the most intriguing target, as DND1 has been shown to modulate microRNA activity by binding to the microRNA targeting sequences on the 3’-UTR of the targeted mRNAs [20]. Therefore, DND1 post-transcriptionally regulates gene expression by inhibiting the microRNA access to the target mRNA. Previous studies demonstrated that DND1 is essential for the motility and survival of germ cells in zebrafish [19], and disruption of DND1 gene can induce testicular germ cell tumors in mice [22].

Our functional analysis confirmed that DND1 is a direct target of miR-24. Furthermore, the miR-24 mediated regulation of DND1 expression also inferences the expression of CDKN1B, one of the known DND1 regulating genes [20]. Knockdown of DND1 by siRNA or ectopic transfection of miR-24 led to the reduced expression of CDKN1B. In contrast, miR-24 knockdown-induced up-regulation of DND1 expression led to enhanced CDKN1B expression.

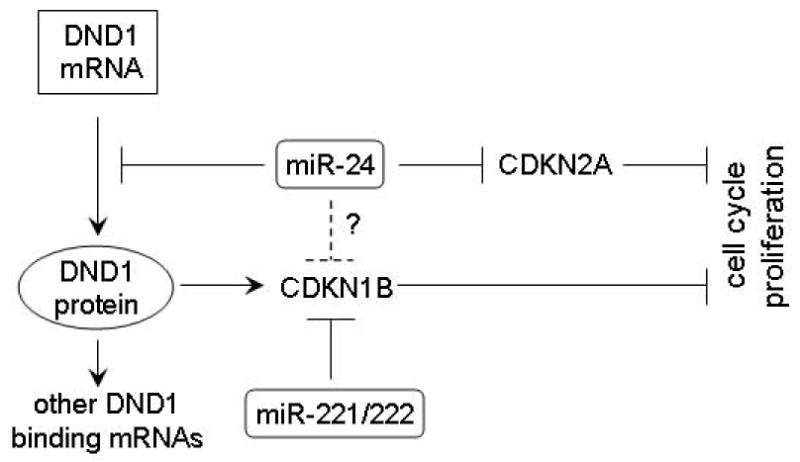

The miR-24 effect on indirect target genes (e.g., CDKN1B) through down-regulating the RNA-binding protein DND1 is intriguing (Figure 5). It is worth knowing that CDKN1B is directly targeted by miR-221/222. We have previously confirmed that miR-222 down-regulates the CDKN1B expression in TSCC cells [17]. Interestingly, the targeting site for miR-221/222 on the 3’-UTR of the CDKN1B mRNA overlaps with the DND1 binding site [20]. This overlap provided an additional in-direct regulatory mechanism wherein DND1 can inhibit microRNA access to the target mRNA, and therefore regulates the miR-221/222 mediated down-regulation of CDKN1B expression. With our newly gained knowledge of miR-24 mediated down-regulation of DND1, we expected that miR-24 and miR-221/222 would have a synergistic effect on CDKN1B expression. However, while both miR-24 and miR-221/222 altered the CDKN1B expression independently, no synergistic effect was observed on CDKN1B expression when cells were concurrently treated with miR-24 and miR-221/222 (data not shown). It appears that the miR-221/222 mediated regulation of CDKN1B gene expression is not interacting with the miR-24/DND1 pathway. Alternatively, it is possible that the potential synergistic effect of miR-24 and miR-221/222 on CDKN1B expression may involve additional unknown molecular regulator(s). It is worth knowing that DND1 prohibits the accessibility of several other microRNAs to their target mRNAs [20], and appears to be a general biological function of DND1. Similarly, HuR, another RNA-binding protein, has also been shown to inhibit miR-122-mediated repression of gene expression by binding to the 3’-UTR of the target gene mRNA [23]. Together, these observations indicate that microRNAs regulate target gene expression through different mechanisms, including direct cis-regulation (miR-221/222 direct targeting CDKN1B) and indirect trans-regulation (miR-24 indirect controlling of CDKN1B gene expression by targeting RNA-binding protein DND1).

Figure 5. Potential mechanisms utilized by miR-24 to regulate cell proliferation in TSCC.

Our bioinformatics analysis also predicted that CDKN1B is directly targeted by miR-24. A highly conserved binding site for miR-24 was predicted in the 3’-UTR of the CDKN1B mRNA. However, our luciferase reporter gene assay failed to confirm a functional interaction of miR-24 and this binding site (data not shown). Therefore, it appears that CDKN1B is not directly targeted by miR-24 in our system. Nevertheless, it remains possible that miR-24 may directly target CDKN1B in other cell types or different biological systems. Our data also confirmed the previous observation that miR-24 suppress the expression of CDKN2A [21], another important cell cycle regulator. Taken together, these results suggest that miR-24 is a putative oncogenic microRNA in TSCC. This is further supported by recent observation that enhanced miR-24 level is associated with the progression of OSCC [10].

In summary, miR-24 is a multi-functional molecule regulator that regulates a variety of biological processes. One of its major roles in TSCC is regulating cell proliferation and apoptosis by targeting inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases (e.g., CDKN1B and CDKN2A). Furthermore, the results from the present study suggest an intriguing mechanism for miR-24 to express its effects through targeting DND1, which in turn regulates a group of downstream genes at post-transcriptional levels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH PHS grants K22DE014847, RO1CA139596, RO3CA135992, and a grant from Prevent Cancer Foundation (to X.Z.). We thank Ms. Katherine Long for her editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, Samuels A, Tiwari RC, Ghafoor A, Feuer EJ, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2005. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(1):10–30. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(4):225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Croce CM. Causes and consequences of microRNA dysregulation in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(10):704–714. doi: 10.1038/nrg2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong TS, Liu XB, Wong BY, Ng RW, Yuen AP, Wei WI. Mature miR-184 as Potential Oncogenic microRNA of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Tongue. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(9):2588–2592. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kozaki K, Imoto I, Mogi S, Omura K, Inazawa J. Exploration of tumor-suppressive microRNAs silenced by DNA hypermethylation in oral cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68(7):2094–2105. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tran N, McLean T, Zhang X, Zhao CJ, Thomson JM, O’Brien C, Rose B. MicroRNA expression profiles in head and neck cancer cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;358(1):12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.03.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hebert C, Norris K, Scheper MA, Nikitakis N, Sauk JJ. High mobility group A2 is a target for miRNA-98 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2007;6:5. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang X, Tang S, Le SY, Lu R, Rader JS, Meyers C, Zheng ZM. Aberrant expression of oncogenic and tumor-suppressive microRNAs in cervical cancer is required for cancer cell growth. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(7):e2557. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu CG, Ambs S, Cimmino A, Petrocca F, Visone R, Iorio M, Roldo C, Ferracin M, Prueitt RL, Yanaihara N, Lanza G, Scarpa A, Vecchione A, Negrini M, Harris CC, Croce CM. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(7):2257–2261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510565103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin SC, Liu CJ, Lin JA, Chiang WF, Hung PS, Chang KW. miR-24 up-regulation in oral carcinoma: positive association from clinical and in vitro analysis. Oral Oncol. 2010;46(3):204–208. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park N-H, Min B-M, Li S-L, Huan MZ, Cherrick HM, Doniger J. Immortalization of normal human oral keratinocytes with type 16 human papillomavirus. Carcinogenesis. 1991;1:1627–1631. doi: 10.1093/carcin/12.9.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu X, Jiang L, Wang A, Yu J, Shi F, Zhou X. MicroRNA-138 suppresses invasion and promotes apoptosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Lett. 2009;286(2):217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19(1):92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krek A, Grun D, Poy MN, Wolf R, Rosenberg L, Epstein EJ, MacMenamin P, da Piedade I, Gunsalus KC, Stoffel M, Rajewsky N. Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat Genet. 2005;37(5):495–500. doi: 10.1038/ng1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffiths-Jones S, Saini HK, van Dongen S, Enright AJ. miRBase: tools for microRNA genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Database issue):D154–158. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu X, Yu J, Jiang L, Wang A, Shi F, Ye H, Zhou X. MicroRNA-222 Regulates Cell Invasion by Targeting Matrix Metalloproteinase 1 (MMP1) and Manganese Superoxide Dismutase 2 (SOD2) in Tongue Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cell Lines. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2009;6(3):131–139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu JH, Wang AX, Huang HZ, Wang JG, Pan CB, Zhang B. Survivin shRNA induces caspase-3-dependent apoptosis and enhances cisplatin sensitivity in squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Oncol Res. 2010;18(8):377–385. doi: 10.3727/096504010x12644422320663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matin A. What leads from dead-end? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64(11):1317–1322. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6433-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kedde M, Strasser MJ, Boldajipour B, Oude Vrielink JA, Slanchev K, le Sage C, Nagel R, Voorhoeve PM, van Duijse J, Orom UA, Lund AH, Perrakis A, Raz E, Agami R. RNA-binding protein Dnd1 inhibits microRNA access to target mRNA. Cell. 2007;131(7):1273–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lal A, Kim HH, Abdelmohsen K, Kuwano Y, Pullmann R, Jr, Srikantan S, Subrahmanyam R, Martindale JL, Yang X, Ahmed F, Navarro F, Dykxhoorn D, Lieberman J, Gorospe M. p16(INK4a) translation suppressed by miR-24. PLoS One. 2008;3(3):e1864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Youngren KK, Coveney D, Peng X, Bhattacharya C, Schmidt LS, Nickerson ML, Lamb BT, Deng JM, Behringer RR, Capel B, Rubin EM, Nadeau JH, Matin A. The Ter mutation in the dead end gene causes germ cell loss and testicular germ cell tumours. Nature. 2005;435(7040):360–364. doi: 10.1038/nature03595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhattacharyya SN, Habermacher R, Martine U, Closs EI, Filipowicz W. Relief of microRNA-mediated translational repression in human cells subjected to stress. Cell. 2006;125(6):1111–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.