Abstract

Raltegravir is an FDA approved inhibitor directed against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) integrase (IN). In this study, we investigated the mechanisms associated with multiple strand transfer inhibitors capable of inhibiting concerted integration by HIV-1 IN. The results show raltegravir, elvitegravir, MK-2048, RDS 1997, and RDS 2197 all appear to encompass a common inhibitory mechanism by modifying IN-viral DNA interactions. These structurally different inhibitors bind to and inactivate the synaptic complex, an intermediate in the concerted integration pathway in vitro. The inhibitors physically trap the synaptic complex thereby prevent target DNA binding and thus concerted integration. The efficiency of a particular inhibitor to trap the synaptic complex observed on native agarose gels correlated with its potency for inhibiting the concerted integration reaction, defined by IC50 values for each inhibitor. At low nM concentrations (<50 nM), raltegravir displayed a time-dependent inhibition of concerted integration, a property associated with slow-binding inhibitors. Studies of raltegravir resistant IN mutants N155H and Q148H without inhibitors demonstrated that their capacity to assembly the synaptic complex and promote concerted integration were similar to their reported virus replication capacities. The concerted integration activity of Q148H showed a higher cross-resistance to raltegravir than observed with N155H providing evidence as to why Q148H pathway with secondary mutations is the predominant pathway upon prolong treatment. Notably, MK-2048 is equally potent against wild type IN and raltegravir resistant IN mutant N155H suggesting this inhibitor may bind similarly within their drug-binding pockets.

Integration of the linear HIV-1 cDNA into the host genome results in a permanent reservoir for the provirus. Integration is a multistep process mediated by viral integrase (IN). In the first step, within the cytoplasmic preintegration complex (PIC), IN processes a dinucleotide at the 3′-end of viral long terminal repeat (LTR) termini. After nuclear transport of the PIC, IN mediates the covalent joining of the 3′-OH recessed ends into cellular DNA by a concerted integration mechanism. Raltegravir (RAL) is the first FDA approved inhibitor that targets HIV-1 IN by inhibiting the strand transfer or joining reaction at low nM concentrations (1).

RAL alone or in combination with other inhibitors targeting reverse transcriptase (nucleoside and non-nucleoside analogs) and protease have been successfully used in patients (2, 3). RAL has been effective in patients where previous antiretroviral treatments have failed (3) and in drug naïve patients (4). Treatment with RAL also results in the emergence of resistant viruses containing mutations in IN. The development of RAL resistance mutations in IN does not result from any natural polymorphism found in RAL naïve patients (5). In most patients, mutations in IN responsible for RAL failure are represented in two independent genetic pathways; N155H and Q148H/R/K accounting for a severe loss (10–25 fold) in susceptibility to RAL with additional secondary mutations (6). A third pathway having a Y143R/C mutation has been observed in a smaller patient population (6). Studies indicate these three pathways are independent and non-overlapping (7, 8). In the patients enrolled for elvitegravir (EVG) studies, T66I, E92Q, Q148R and N155H mutations are primary contributors to EVG resistance (9–11). The resistant mutants are stable and persist even after the withdrawal of the drug (12).

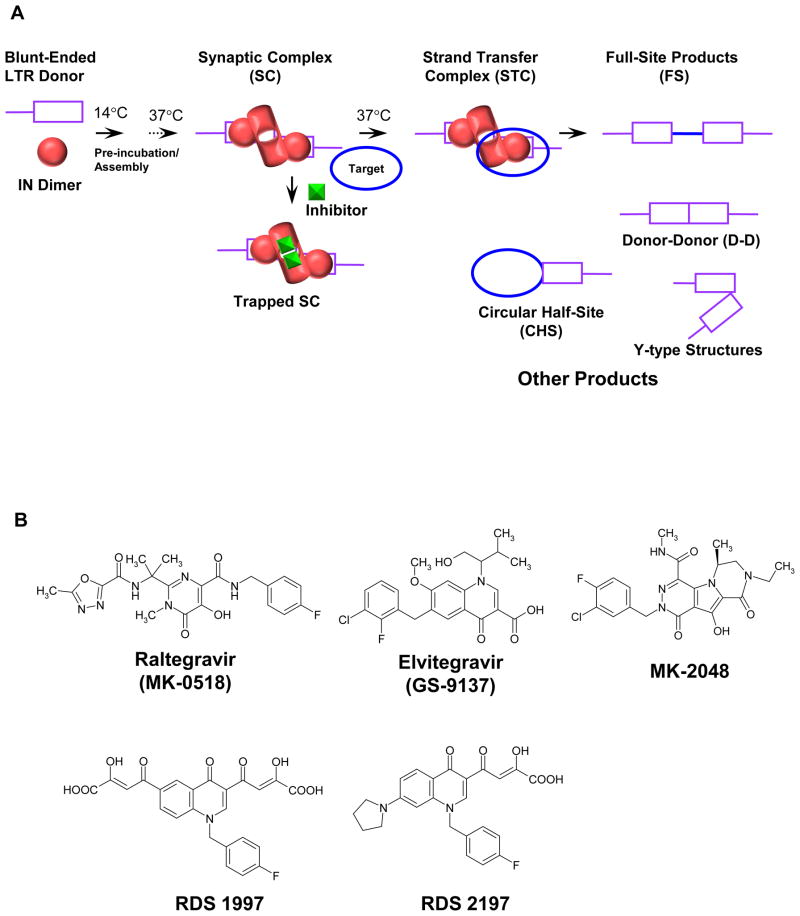

In earlier studies, we showed that a strand transfer inhibitor (STI) binds to the synaptic complex (SC) which blocks target binding, thus preventing the formation of the strand transfer complex (STC) and concerted integration (13)(Figure 1A). The STC is the terminal nucleoprotein complex in the concerted integration pathway in vitro (14). SC contains two LTR ends held together non-covalently by IN and is the intermediate in the concerted integration pathway (13). SC possesses biochemical properties similar to the PIC in vivo (13, 15, 16). The LTR DNA blunt-ends are slowly processed by IN within SC and upon binding to supercoiled target DNA, concerted integration occurs (13, 14, 17, 18). Concerted integration requires an IN tetramer at the viral DNA ends (14, 19, 20). Inhibitor bound SC is termed “trapped SC” and is not competent to bind target DNA (Figure 1A). Inhibitors do not inhibit either the assembly of the SC (13) nor significantly modify the length of ~32 bp DNaseI protective footprint observed on U3 and U5 ends in SC without inhibitor (15). However, L-870,810, a naphthyridine carboxamide inhibitor (21) modifies the location of the 5′-DNA ends in SC (15). The energy transfer between the two LTR ends (5′-end labeled with Cy3 and Cy5) within SC formed in presence of L-870,810 was significantly decreased in comparison to SC formed in the absence of the inhibitor thus, providing a structural explanation for the inability of target DNA to bind trapped SC (15).

Figure 1.

Schematic for assembly of the SC and the concerted integration reaction. (A) IN dimers assemble onto HIV-1 LTR forming the SC where two LTR ends are non-covalently juxtaposed by IN. The IN dimer bound at each LTR terminus form the active tetramer and is drawn differently to reflect the conformational change associated with 3′-processing of the LTR DNA ends. In the presence of supercoiled target DNA, SC is converted to the STC, the terminal nucleoprotein complex in the concerted integration pathway. STIs prevent target DNA binding to SC resulting in the accumulation of inactivated or trapped SC and thus inhibition of STC formation. Deproteinization of the STC yields the concerted or FS integration product. Other integration products formed in the reaction are CHS, D-D, and Y-type products. (B) Structure of STIs. RDS 1997 is compound 8 in ref (31) and RDS 2197 is compound 6i in ref (32).

The effects of strand transfer inhibitors (STIs) on the integration of HIV-1 DNA in vivo have established: 1) the concentration to effectively inhibit HIV-1 replication is in the low nM concentration (~20–40 nM); 2) the copies of integrated DNA are significantly decreased in comparison to wt infection; and 3) the number of 2-LTR circles in the nucleus increases multifolds suggesting that some or most of the PICs are imported into the nucleus upon treatment of virus-infected cells with inhibitors. The cytoplasmic PIC is non-functional in HIV-1 infected cells grown in the presence of a diketo acid inhibitor (22).

In this report, we have examined the early events on how STIs interact with IN using SC as a model for the PIC. We investigated the effectiveness of RAL, MK-2048, EVG, RDS 1997, and RDS 2197 on physically trapping and inactivating SC. Trapping of SC appears to be a universal inhibitory mechanism for these structurally distinct compounds. The efficiency of an inhibitor to initiate the trapping of SC at low nM concentrations (10–20 nM) was directly proportional to its potency in inhibiting concerted integration in vitro, similar to in vivo results (1, 11). Inhibition of concerted integration at a given low nM concentration (<50 nM) of RAL was time-dependent. We established that MK-2048 is equally active against IN possessing the RAL resistant N155H mutation in comparison to wt IN. HIV-1 containing the N155H mutation has a similar replication capacity (~70%) of wild type (wt) HIV-1 (7, 23, 24). With N155H IN, the assembly of SC and concerted integration were delayed relative to wt IN suggesting a possible biochemical mechanism why IN is partially defective in HIV-1 possessing this mutation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

DNA Substrates

Single-ended U5 (1.6 kb) and U3 (2.4 kb) DNA containing natural HIV-1 blunt ends were obtained by NcoI digestion of ScaI linearized Mini-HIV pU3U5 (17, 25). ScaI linearized and dephosphorylated DNA was labeled with γ-32P[ATP] and digested with NcoI. The 5′-end of the non-transferred DNA strand is labeled. Fragments containing single U5 and U3 ends were purified from agarose gels by Qiaquick Gel Extraction kit (Qiagen).

Purification of IN

wt HIV-1 (pNYstrain) IN was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) (Stratagene) and purified to near homogeneity (26, 27). IN mutants N155H and Q148H were constructed in the pNY clone, expressed, and purified similar to wt IN. From sequence analysis, IN does not contain any natural polymorphism for RAL or EVG resistance as observed in IN inhibitor-naïve patients (5).

HIV-1 IN Inhibitors

RAL and MK-2048 were generously supplied by Merck Research Laboratories. MK-2048 is effective against the resistant variants produced using RAL (28, 29). EVG (30), RDS 1997 (31) and RDS 2197 (32) were kind gifts of Dr. Yves Pommier and Christophe Marchand (National Cancer Institute). Their chemical structures are shown in Figure 1B. Each inhibitor was dissolved in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and stocks (10 mM) were stored at ′70°C in small aliquots. A fresh aliquot was used in each experiment after making appropriate dilutions in DMSO. The quantity of DMSO was kept constant at 1% (v/v) in the reaction mixture.

Concerted Integration Assay

The assays with or without inhibitors were performed as described (27, 33). HIV-1 IN was pre-assembled with 5′-end (γ-32P) labeled U5 or U3 DNA in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM MgCl2, 25 μM ZnCl2, and 10% poly (ethylene glycol) 6000 at 14°C for 15 min. IN and donor concentrations were described for each experiment. Inhibitor and supercoiled target DNA (pBSK2 Zeo) were added and samples incubated at 37°C, typically for 2 h. The reactions were stopped with EDTA at a final concentration of 25 mM. An aliquot of the reaction products was subjected to 0.7% native agarose electrophoresis at 4°C to determine the effect of inhibitors on SC. The remaining samples were deproteinized with sodium dodecyl sulfate (0.5%) and proteinase K (1 mg/ml) at 37°C for 30 min. Deproteinized samples were subjected to electrophoresis on a 0.7% agarose gel to determine the quantities of concerted or full-site (FS), donor-donor (D-D), and circular half-site (CHS) products (Figure 1A). The IC50 values of STIs to inhibit the formation of these DNA products were determined (13).

DNaseI Footprint Analysis of IN-DNA Complexes Formed in the Presence of RAL

HIV-1 SC and higher order synaptic complex (H-SC) were formed with 5′-32P end-labeled 1.6 kb U5 DNA or 2.4 kb U3 DNA (3nM) and 60 nM of wt IN under standard integration assay conditions in presence of RAL (750 nM) at 37°C for 2 h. DNaseI treatment of the complexes and their isolation were performed as described previously (15).

RESULTS

A Uniform Mechanism for Physical Trapping of HIV-1 SC by Different Structural Classes of STIs

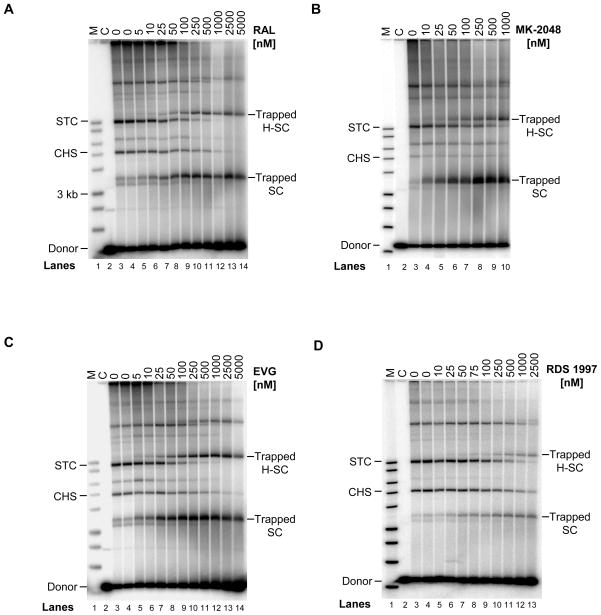

A naphthyridine carboxamide inhibitor (L-870,810) at low nM concentrations was capable of trapping HIV-1 SC which prevented target DNA binding and thus its subsequent conversion to STC (13). We determined here that trapping of SC by IN inhibitors is a universal phenomenon and is a predictor for potency of a compound to inhibit concerted integration in vitro. We investigated various STIs (RAL, MK-2048, EVG, RDS 1997 and RDS 2197) for their ability to trap SC and H-SC. H-SC possesses physical properties observed with SC and is a nucleoprotein complex that contains multimeric forms of SC on native agarose gels (13, 15). Upon increasing concentrations, RAL, MK-2048, and EVG efficiently trapped SC and H-SC thus blocking the formation of STC (Figure 2A, 2B, and 2C, respectively). In all cases, the STC disappeared in a proportional manner with increasing concentrations of inhibitors in comparison to the control reactions without inhibitors (Figure 2, lanes 3 or 4, marked zero at top). With these three inhibitors, trapped SC and H-SC were first detected at ≥10 nM and their quantities increased with increasing inhibitor concentrations. Generally, trapped SC is detected prior to and in larger quantities relative to trapped H-SC. Once the maximum quantities of trapped SC and H-SC were produced with each inhibitor at a specific inhibitor concentration, this quantity remained essentially stable. With RDS 1997, a higher concentration of ≥50 nM was required to detect both trapped complexes (Figure 2D). RDS 1997 is a bifunctional quinolinonyl diketo acid derivative which inhibits strand transfer as well as 3′-processing activity of HIV-1 IN (31). With RDS 2197 (32), a mono-quinone inhibitor that preferentially prevents strand transfer, higher amounts of inhibitor (≥250 nM) were required to detect trapped SC and H-SC (data not shown). In summary, physical trapping of SC appears to be a universal property of structurally different IN inhibitors to prevent target DNA binding. This “trapping” property possibly explains why some or all PIC remains intact upon nuclear transport allowing for the efficient formation of 2-LTR circles in virus-infected cells treated with STIs (22, 34–37).

Figure 2.

Structurally diverse inhibitors inhibit HIV-1 concerted integration through a uniform mechanism by physically trapping SC. IN (20 nM) was pre-assembled with 5′-32P end-labeled 1.6 kb U5 blunt-ended DNA (0.5 nM) followed by the addition of target DNA in presence of varying concentrations of STIs for 2 h at 37°C. The panels are: A. RAL; B. MK-2048; C. EVG; and D. RDS 1997. Samples were subjected to 0.7% native agarose gel electrophoresis at 4°C. Lane 1, marked M, contain 32P- labeled molecular weight markers (kb ladder) in all the panels. Lane 2, marked C, is control reaction without IN. Lane 3 and 4, marked 0, are with IN but without any inhibitors for production of STC except, in panel B which has only lane 3 without inhibitor. The inhibitor concentrations are located on the top of each gel. The trapped SC and H-SC formed in presence of inhibitors are marked on right. With increasing concentrations of inhibitors, conversion of SC to STC is prevented resulting in the accumulation of trapped SC and H-SC. In parallel, a decrease in amount of STC formed with increasing inhibitor concentrations is also evident.

Even though a majority of IN-DNA nucleoprotein complexes formed in solution enter the native agarose gel as discrete complexes, some smearing of the complexes is evident throughout and at the top of the gel due to non-specific IN-IN and IN-DNA interactions (Figure 2)(13, 14, 17). With all four inhibitors at higher nM concentrations (≥100 nM), a majority of the labeled DNA is associated with trapped SC and H-SC. A similar result was evident in the presence of L-870,810 (13). These results suggest that these non-specific interactions were disrupted in the presence of inhibitors possibly due to a slight modification of the surface charge on IN and to the disappearance of the STC at higher inhibitor concentrations.

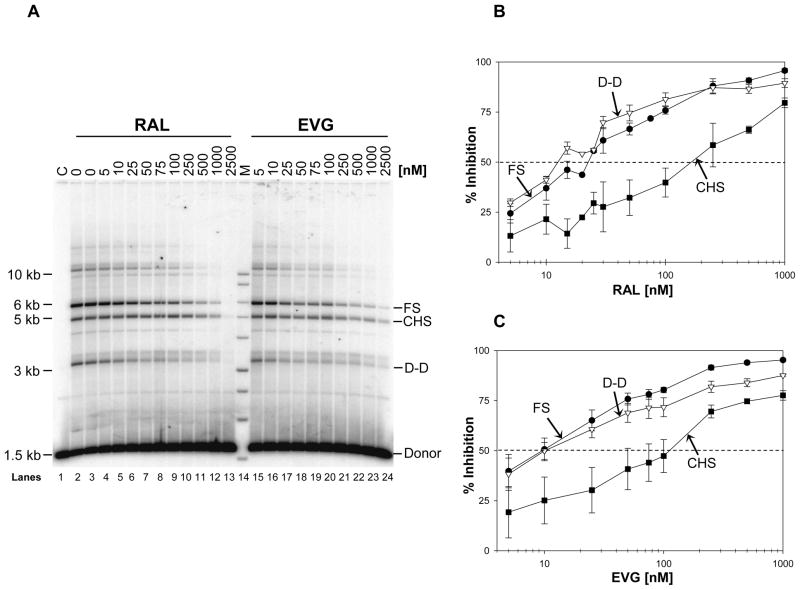

Deproteinization of the HIV-1 nucleoprotein complexes was necessary to determine the IC50 values (Table 1) for inhibition of concerted or FS, D-D, and CHS integration reactions (Figure 3). The CHS product is produced by the insertion of a single LTR end into supercoiled DNA (Figure 1A) (26, 38). EVG was the most potent inhibitor of concerted integration with the lowest IC50 value (8.5 ± 1.3 nM) followed by RAL, MK-2048, RDS 1997, and RDS 2197 in the order of increasing IC50 values (Table 1). The same order for IC50 values were obtained for inhibition of D-D and CHS products. It is noteworthy that the IC50 values for inhibiting the D-D reaction were as low as observed for concerted integration while the values for inhibition of the CHS reaction were 4 to 15-fold higher (13, 39). These results suggest a direct correlation between the IC50 value for a particular STI to inhibit concerted or FS products (Table 1) and its ability to trap the SC or H-SC (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Summary of the IC50 (nM) values for different integrase inhibitors with wt and mutant INs*.

| Inhibitor | Products with wt IN | Products with N155H IN | Products with Q148H IN | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FS | DD | CHS | FS | DD | CHS | FS | CHS | |

| EVG | 8.5 ± 1.3 | 8.6 ± 1.2 | 145 ± 5 | 87 ± 7.5 | 62 ± 24 | 250 ± 24 | 173 ± 50 | 230 ± 29 |

| RAL | 21 ± 4 | 14 ± 2.5 | 246 ± 81 | 68 ± 15 | 58 ± 15 | 160 ± 71 | 341 ± 69 | 222 ± 45 |

| MK-2048 | 42 ± 5 | 21 ± 3 | 365 ± 45 | 42 ± 3 | 26 ± 8 | 171 ± 27 | 97 ± 29 | 122 ± 31 |

| RDS 1997 | 90 ± 24 | 66 ± 18 | 352 ± 49 | 150 ± 32 | 87 ± 12 | 245 ± 60 | 500 ± 58 | 363 ± 95 |

| RDS 2197 | 495 ± 76 | 347 ± 42 | 1757 ± 362 | 395 ± 48 | 260 ± 91 | 622 ± 164 | 1021 ± 186 | 822 ± 180 |

The IN-DNA complexes were assembled with IN (20 nM) and 5′-32P end-labeled 1.6 kb U5 substrate (0.5 nM) at 14°C for 15 min. Increasing concentrations of inhibitor along with the supercoiled DNA (1.5 nM) were added and strand transfer was carried out for 2 h at 37°C. In the reactions with N155H and Q148H IN, 30 nM of protein was added and strand transfer was carried out for 3 h at 37°C. The samples were deproteinized and subjected to 0.7% agarose gel electrophoresis. The quantity of each type of product (FS, D-D and CHS) was determined by Image-Quant 5.2 and the inhibition of each product was calculated. The IC50 (nM) for each DNA product with each inhibitor was determined from at least three independent experiments.

Figure 3.

RAL and EVG inhibit concerted integration at low nM concentrations. (A) IN (40 nM) was pre-assembled with 5′-32P end-labeled 1.6 kb U5 blunt-ended DNA substrate (1 nM) at 14°C for 15 min. Upon addition of varying concentrations of inhibitors and supercoiled DNA (1.5 nM), samples were incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Reactions were stopped with EDTA, deproteinized, and the strand transfer products were analyzed on 0.7% agarose gels. Individual products are identified on the right. Lane 1, marked C, contains DNA only without IN. Lanes 2 and 3 are control reactions without inhibitor. Increasing concentrations of RAL were added in lanes 4–13 and EVG in lanes 15–24. Lane 14, marked M, contain 32P- labeled molecular weight markers (kb ladder). (B) Inhibition of concerted or FS, CHS, and D-D products by increasing concentrations of RAL. IN (20 nM) was pre-assembled with 5′-32P end-labeled 1.6 kb U5 blunt-ended DNA substrate (0.5 nM) at 14°C for 15 min. Upon addition of varying concentrations of RAL and supercoiled DNA (1.5 nM), samples were incubated for 2 h at 37°C and processed as mentioned in A. Inhibition of each product (FS, D-D and CHS) was plotted against RAL concentration. The error bars indicate the SD from at least four independent experiments. (C) Inhibition of integration products with increasing concentrations of EVG. Experiments were done as described in panel B. The error bars indicate the SD from at least four independent experiments. The dotted horizontal line indicates 50% inhibition of FS product. The IC50 values for inhibition of FS, D-D, and CHS integration products are summarized in Table 1.

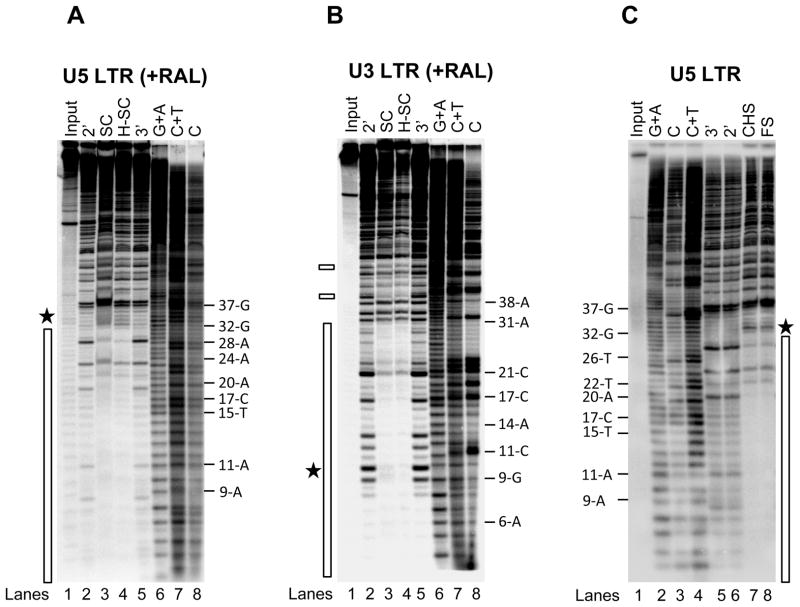

RAL does not Change Overall Binding Properties of IN Multimers onto the LTR Ends

Within the PIC, IN is responsible for the ~200 bp extended protective footprint at the U5 and U3 LTR ends which are independently processed by IN (40). In vitro, IN multimerizes independently on U5 and U3 ends before the assembly of SC and differentially binds the terminal ~32 bp at the U5 and U3 ends, deduced from the DNaseI digestion pattern (15). Similar size protection patterns are observed in FS and CHS products containing U5 or U3 ends (15). In addition, SC and H-SC produced in presence of L-870,810 (750 nM) possess the ~32 bp protective footprint at the U5 end. We determined whether RAL altered the ~32 bp DNaseI protective footprint on U5 and U3 ends. SC and H-SC were formed with IN (60 nM) and 5′-end labeled 1.6 kb U5 blunt-ended DNA (3 nM) in presence of RAL (750 nM) for 2 h at 37°C. An extended incubation time facilitates the accumulation of trapped SC and H-SC (Figure 2). The terminal ~32 bp from the U5 end in both complexes were protected from DNaseI digestion (Figure 4A, lanes 3 and 4, respectively). Enhanced DNaseI digestions immediately upstream of nucleotide 32-G suggested that RAL does not alter the overall binding length of IN to these terminal nucleotides as shown with U5 DNA in the absence of inhibitor (Figure 4C, lanes 7 and 8) (15). SC and H-SC formed with a 2.4 kb U3 blunt-ended DNA in presence of RAL also displayed a ~32 bp protective footprint (Figure 4B, lane 3 and 4) with a few regions of protection between ~40 and 60 bp from the LTR end (shown with small rectangles in Figure 4B). A similar IN protection pattern was observed in FS and CHS products formed with U3 DNA (15). No enhanced DNaseI cleavages were observed at the outside boundary around ~32 bp on U3 (Figure 4B, lane 3 and 4) as shown previously without a inhibitor (15). A notable difference is that the DNaseI major enhancements at 9-G and 6-A observed with U3 without inhibitor (15) were absent in the presence of RAL (Figure 4B, lane 3 and 4). Instead, several minor enhanced cleavages were identified near nucleotides 9-G and 10-G. In summary, RAL does not affect the assembly of IN or overall multimeric structure of IN with either U5 or U3 LTR ends in SC and H-SC.

Figure 4.

RAL does not affect the IN multimeric structure at the LTR ends. (A) IN (60 nM) was pre-assembled with 5′-32P end-labeled 1.6 kb U5 blunt-ended DNA (3 nM) for 15 min at 14°C. RAL (750 nM) and supercoiled DNA (3 nM) were added and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Samples were treated with DNaseI and subjected to native agarose gel electrophoresis. DNA was purified from the trapped SC and H-SC and subjected to denaturing polyacrylamide 15% (w/v) gel electrophoresis. Lane 1, input DNA; lanes 2 and 5, input DNA digested with DNaseI for 2 min and 3 min, respectively; lanes 3 and 4, DNaseI treated SC and H-SC, respectively; lanes 6 to 8, Maxam-Gilbert chemical sequence markers prepared from input DNA. The nucleotide positions are marked on the right. The asterisk indicates enhanced DNaseI digestion and the vertical bar represents the protected DNA region. (B) DNaseI footprint analysis on 2.4 kb U3 blunt-ended DNA. The formation of trapped complexes, DNaseI treatment and sample loading order were identical as described above in A. Nucleotide positions on U3 LTR are on the right. Chemical sequence markers of U3 DNA are in lanes 6 to 8. The vertical bar represents the DNaseI protected region and two minor protected regions beyond 38 bp are marked by small rectangles on the left. (C) IN (80 nM) was pre-assembled with 5′-32P end-labeled 1.6 kb U5 blunt-ended DNA (3 nM) for 15 min at 14°C. Strand transfer was initiated by adding supercoiled DNA (3 nM) and incubating at 37°C for 2 h. Samples were treated with DNaseI, deproteinized and subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis. DNA purified from FS and CHS products were subjected to denaturing polyacrylamide 15% (w/v) gel electrophoresis. Lane 1, input DNA; lanes 2 to 4 Maxam-Gilbert chemical sequence markers prepared from input DNA; lane 5 and 6 contain input DNA digested with DNaseI for 3 min and 2 min, respectively; lanes 7 and 8, DNaseI treated CHS and FS, respectively. The nucleotide positions are marked on the left. The asterisk indicates enhanced DNaseI digestion and the vertical bar represents the protected DNA region.

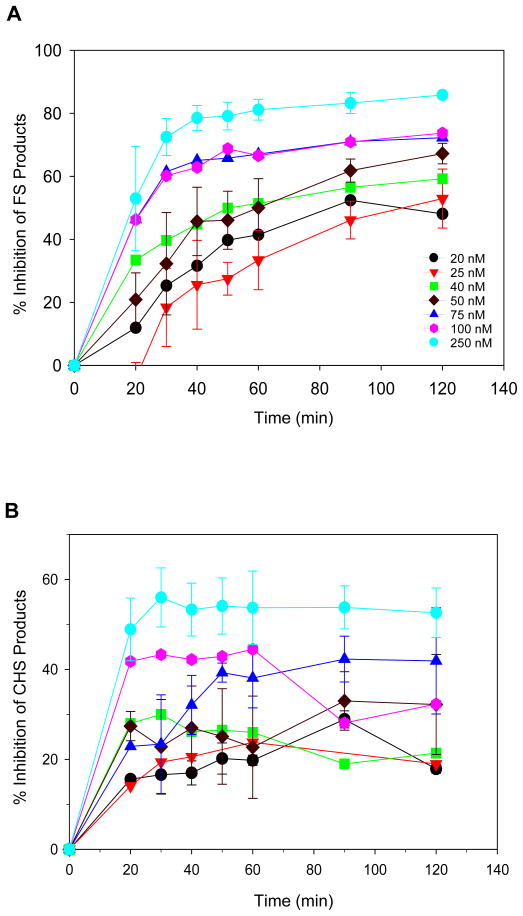

Time-Dependent Inhibition of Concerted Integration at Low nM Concentrations of RAL

STIs appear to follow a two-step binding mode wherein an inhibitor binds to IN within complexes that contain a single DNA end with lower affinity and is subsequently converted to a higher affinity complex upon isomerization of the IN-DNA complex (41, 42). In order to characterize the inhibition profile for concerted or FS integration at a constant inhibitor concentration, a time-dependent assay was performed (Figure 5A). IN-DNA complexes were produced with IN (20 nM) and U5 blunt-ended DNA (0.5 nM) in presence of supercoiled DNA and varying concentrations of RAL. Samples were taken before, at, and after the maximum formation of SC at ~30 min (Figure 6A) (13, 27). Inhibition of FS and CHS products at each inhibitor concentration was plotted against time (Figure 5). With time, the rate of inhibition increased the most for inhibition of FS products at the lower inhibitor concentrations (Figure 5A). For example, at 25 nM similar to the IC50 value of RAL (Table 1), inhibition of FS products was ~3-fold higher at 120 min when compared to inhibition at 30 min, suggesting time-dependent inhibition. Similar inhibitory profiles were most readily discernable at ≤50 nM of RAL and less at higher concentrations. In contrast, the inhibition of CHS products was near maximum for each specific inhibitor concentration after 30 min and did not increase significantly over a longer reaction time (Figure 5B). In summary, the different inhibition kinetics between FS and CHS products suggest distinct structural differences in IN-single DNA complexes that produce the CHS products and the SC that produces the FS products. The continuous increase in inhibition of FS product with time resembles a hallmark feature of slow-binding inhibitors (43) indicating that RAL possibly acts as a slow binding inhibitor (41).

Figure 5.

Time-dependent inhibition of concerted integration at a constant RAL concentration. (A) Kinetics for inhibition of concerted or FS integration products. IN-DNA complexes were pre-assembled with IN (20 nM) and 5′-32P end-labeled 1.6 kb U5 blunt-ended DNA (0.5 nM) at 14°C for 15 min. A specific concentration of RAL was added along with supercoiled DNA (1.5 nM) and the samples were incubated at 37°C for various times from 20 min to 120 min. The figure insert identifies each RAL concentration used. Deproteinized products were subjected to 0.7% agarose gel electrophoresis. The quantities of FS and CHS products were determined and the % inhibition was determined with reactions performed in parallel without RAL. The average percentage of U5 DNA incorporated into the FS product without inhibitor at 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 90 and 120 min were 0.9, 2.3, 4.4, 6.5, 8.8, 15.2 and 18.3%, respectively. The amount of U5 DNA incorporated into CHS products in absence of inhibitor was 2.0, 3.4, 4.6, 5.5, 6.2, 7, and 6.3% at the corresponding times. The error bars indicate SD for at least two independent experiments per inhibitor concentration. (B) The % inhibition of CHS products was determined in parallel as described in panel A. The symbols are the same as shown in the panel A insert.

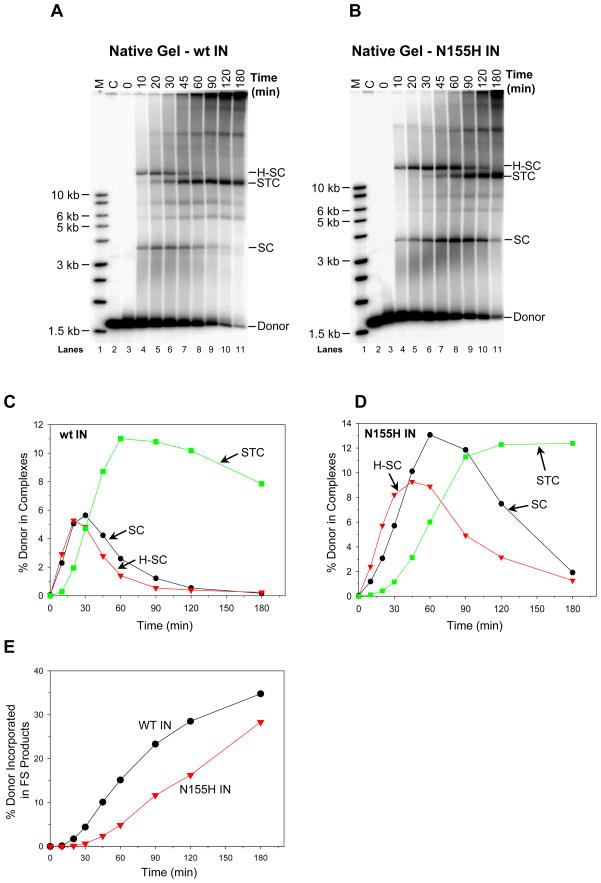

Figure 6.

N155H IN possesses slower assembly and concerted integration kinetics in comparison to wt IN. In panel (A) wt IN (20 nM) and in panel (B) N155H IN (30 nM) were pre-assembled with 5′-32P end-labeled 1.6 kb U5 blunt-ended DNA (0.5 nM) for 15 min at 14°C. Supercoiled DNA (1.5 nM) was added to study the assembly kinetics of SC, H-SC, and STC from 0 min to 180 min at 37°C. (C) Kinetics of formation of SC, H-SC, and STC with wt IN. The percentage of input DNA incorporated into each nucleoprotein complex versus time was plotted. (D) Kinetics of formation of SC, H-SC, and STC with N155H IN. (E) Aliquots of the above experiments with wt and N155H IN were deproteinized and the quantities of FS products were determined and plotted. The total quantities of FS products after 180 min were 35% and 27%, respectively.

IN with the N155H Mutation Possesses Slower Assembly Properties for SC and Concerted Integration Kinetics than wt IN

N155H is a primary mutation in IN that arises in patients undergoing RAL and EVG therapy (7, 10). HIV-1 carrying the N155H mutation in IN, replicates at ~70% efficiency relative to wt virus (7, 23, 24). We compared the assembly properties of SC using wt and N155H IN (Figure 6). With wt IN, SC and H-SC reached near maximum quantities at ~30 min (Figures 6A, 6C)(13) whereupon both species gradually disappear by ~60 min as they are converted gradually to STC (Figure 6A, lane 5 to 11). In contrast, N155H displayed overall slower assembly kinetics for SC and H-SC (Figures 6B and 6D). In multiple experiments, the N155H nucleoprotein complexes were generally delayed showing a maximum combined quantity for these two complexes between ~45 to 90 min (Figure 6D). Thus, the initial stage of STC formation by N155H (Figure 6D) was also delayed compared to wt IN (Figure 6B). In addition with N155H, the total conversion of SC and H-SC to STC (Figure 6D) was slower in comparison to wt IN (Figure 6C). In confirmation, the formation of FS products with N155H also followed similar delayed kinetics relative to wt IN (Figure 6E). The results suggest that the N155H mutation affects the ability of IN to properly assemble SC in a timely fashion and thus affect concerted integration which is at ~70% of wt levels.

IN with a Q148H Mutation Possesses Markedly Reduced Concerted Integration Activity

The second predominant pathway leading to the development of drug-resistance in RAL therapy involves residue Q148. In vivo, HIV-1 with the Q148H mutation possesses ~30% infectivity and ~15% replication capacity of wt virus (24). The overall catalytic activity for strand transfer with recombinant IN with the Q148H mutation using LTR oligonucleotides as substrates was also ~30% of wt IN, after normalization of decreased 3′-processing activity (24). Lastly, residue Q148 interacts with the terminal 5°C on the non-processed end via a hydrogen bond and is important for efficient strand transfer activity (44). The concerted integration assay employing the natural blunt-ended U5 substrate takes in account the ability of IN to assemble SC, promote 3′-OH processing of two LTR ends, and produce FS products. In multiple experiments, formation of FS products by Q148H was delayed and reduced to ~30% level relative to wt IN upon incubation up to 3 h at 37°C (Supporting Information Figure S1). In contrast, the quantity of CHS products produced by Q148H was ~60 to 70% of wt IN level suggesting that this single 3′-OH processing step necessary for strand transfer was not severely affected under our assay conditions. In summary, the Q148H substitution decreased the ability of IN to promote concerted integration.

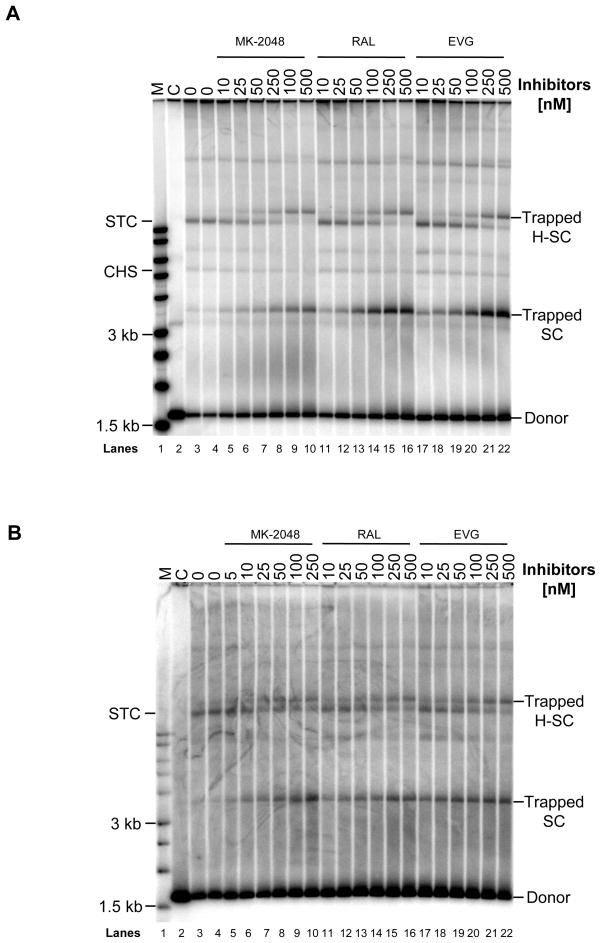

Formation of Trapped SC Produced by N155H and Q148H in the Presence of MK-2048, RAL, or EVG

We determined the resistance profile of N155H and Q148H against a spectrum of inhibitors including MK-2048, RAL, and EVG by studying their effect on forming trapped SC (Figure 7) and concerted integration activity (Figure 8). All three inhibitors were able to trap SC and H-SC formed with N155H (Figure 7A) and Q148H (Figure 7B) to varying degrees after incubation for 3 h at 37°C. With increasing concentrations of inhibitors, the quantity of trapped SC and H-SC increased with a simultaneous decrease of STC formation, similar to the pattern observed with wt IN (Figure 2). A similar pattern was observed with N155H and Q148H using RDS 1997 and RDS 2197 (data not shown). Even though Q148H had significantly lower concerted integration activity than wt IN, the same trend of trapping SC by STIs appears to also occur (Figure 7B). In summary, similar qualitative patterns for trapping of SC by STIs with wt, N155H, and Q148H IN were observed.

Figure 7.

Structurally diverse STIs are able to trap SC and H-SC formed with N155H and Q148H IN. N155H or Q148H IN (30 nM) were pre-assembled with 5′-32P end-labeled 1.6 kb U5 DNA substrate (0.5 nM) at 14°C for 15 min. Inhibitor and a supercoiled DNA (1.5 nM) were added and the integration reaction was allowed for 3 h at 37°C. Reactions were stopped with 25 mM EDTA and aliquots were subjected to native agarose gel electrophoresis. Panel A and B shows the products obtained with N155H and Q148H IN, respectively. In both panels, lane 1, marked M contains 32P- end-labeled molecular weight markers. Lane 2, marked C, is control reaction without IN. Lane 3 and 4, marked 0, are with IN but without inhibitor for production of STC. Lanes 5 to 10 contain increasing concentrations of MK-2048, lanes 11–16 contain RAL and lanes 17–22 contain EVG. Trapped SC and H-SC are marked on right. A decrease in formation of STC with increasing concentrations of inhibitor is evident.

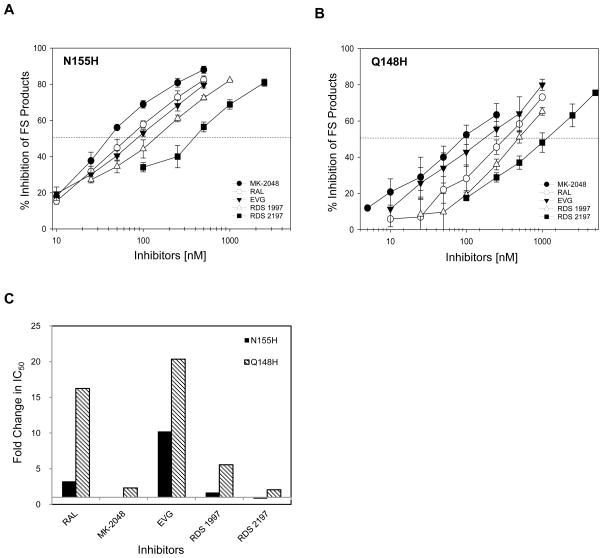

Figure 8.

Inhibition profile of concerted FS product obtained from N155H and Q148H IN with various STIs. IN (30 nM) of each mutant were assembled with 5′-32P end-labeled 1.6 kb U5 DNA substrate (0.5 nM) at 14°C for 15 min. Inhibitor and supercoiled DNA (1.5 nM) were added and the reaction was allowed for 3 h at 37°C. Reactions were stopped with 25 mM EDTA and deproteinized with SDS (0.5%) and proteinase K (1 mg/ml). The percentages of donor DNA incorporated into FS product with or without inhibitors were determined. (A) Plot of inhibition of FS products obtained with N155H IN with increasing concentrations of various STIs. (B) Plot of inhibition of FS products obtained with Q148H IN with increasing concentrations of various STIs. In both panels A and B, the error bars indicate SD from at least four independent experiments. The dotted horizontal line indicates 50% inhibition of FS product. The IC50 value for integration products is summarized in Table 1. (C) Graphical representation of cross-resistance for various inhibitors against N155H and Q148H. IC50 values for inhibiting the FS products obtained with N155H and Q148H IN by various inhibitors were compared with the IC50 values obtained with wt IN (Table 1). Fold changes in IC50 value for FS products obtained with N155H and Q148H IN relative to wt IN were plotted.

Quantitative Analysis for Inhibition of Concerted Integration with N155H and Q148H

We quantitatively determined the interactions of MK-2048, RAL, and EVG with N155H and Q148H (Figure 8). In vivo, MK-2048 had an excellent antiviral activity (IC95 of 41 nM in 50% normal human serum) and possessed a higher genetic barrier than RAL (29). MK-2048 had a similar IC50 value for N155H (42 ± 3 nM) as wt IN (42 ± 5 nM) for inhibition of FS products (Table 1)(Figure 8A). The IC50 values for inhibition of FS products with N155H were 68 ± 15 nM and 87 ± 7.5 nM for RAL and EVG, respectively (Table 1). The N155H substitution provides greater resistance to EVG (10-fold) than RAL (3-fold) in comparison to wt IN (Table 1), as reported earlier (29, 45). The relative resistant profile of these inhibitors along with RDS 1997 and RDS 2197 against N155H as compared to wt IN were illustrated in Figure 8C. In summary, MK-2048 is equally effective against wt IN and N155H for inhibition of concerted integration.

Concerted integration catalyzed by Q148H was found to be resistant to all of the inhibitors to various degrees (Figure 8B). The IC50 values to inhibit the formation of FS products were determined (Table 1). Expectedly, Q148H had high resistance to RAL (16-fold) and EVG (20-fold) as compared to wt IN (Figure 8C). MK-2048 was modestly active against Q148H with only a 2-fold higher IC50 value for inhibition of FS products.

DISCUSSION

STIs appear to be “interfacial inhibitors” that stably associate with an intermediate IN-DNA complex in the integration pathway (46). Interfacial inhibitors bind at the interface of two (or more) macromolecules in a multimeric complex which is undergoing a conformational change, thus blocking their biological function (47). In the concerted integration pathway, we identified SC as a transient intermediate (13) which upon binding supercoiled DNA produces the STC (14). L-870,810 inhibited the conversion of SC into STC resulting in the accumulation of inactivated or physically trapped SC (13, 16). From this study, we conclude that trapping of SC with STIs possessing diverse structures may be a universal phenomenon with wt IN and at least with several raltegravir resistant IN mutants. We also observed a direct correlation in the ability of an inhibitor to trap SC in a concentration dependent manner with the potency of the inhibitor to prevent concerted integration. The potency order for STIs to prevent concerted integration was EVG > RAL > MK-2048 > RDS 1997 > RDS 2197 (Table 1).

STIs do not affect the assembly of SC, rather they alter the structure of SC rendering it inactive and unable to bind target DNA (13, 15, 16). The major DNA binding and multimerization properties of IN on U5 ends in the presence of RAL were not altered (Figure 4A) relative to its absence (Figure 4C) (15). SC and H-SC displayed a ~32 bp DNaseI protective footprint with RAL present including the DNaseI enhanced cleavages at ~32 nucleotides from the 5′-end of the non-transferred DNA strand (Figure 4A). The length of the ~32 bp protected region in these same complexes formed with U3 LTR ends (Figure 4B) was also similar to the footprint pattern observed without inhibitors (15). But, major enhanced cleavages with U3 at nucleotides 6-A and 9-G observed in absence of inhibitor (15) were changed in presence of RAL with minor enhancements at 9-G and 10-G (Figure 4B). RAL inhibits the formation of integration products using U3 substrate with similar potency as observed with U5 (data not shown). These structural results with SC are consistent with the observation that RAL and other STIs do not disturb the cytoplasmic PIC and its nuclear transport which results in an increased formation of the 2-LTR circle junction DNA in the nucleus.

What are the structural changes induced by inhibitors between the DNA ends in SC responsible for disturbing target binding? The fluorescence resonance energy transfer efficiency between the 5′-Cy3 and Cy5 labeled U5 ends in HIV-1 SC was significantly decreased (85%) within trapped SC (15). The calculated distance between the 5′-ends of the non-transferred strand increased from 46 ± 3 Å in SC formed without inhibitor to 77 ± 6 Å in the SC formed in presence of L-870,810. Crystal structure data of prototype foamy virus IN-DNA complex bound to RAL also showed that overall binding of IN to DNA is not affected, however, the reactive 3′-OH group was moved more than 6 Å away from the active site by RAL (20). These two studies and the altered internal DNaseI footprints in U5 and U3 in the presence of L-870,810 and RAL, respectively, suggest changes in IN-DNA interactions produced by inhibitors renders the IN-DNA complex inactive for integration.

Mutations at N155 and Q148 constitute two major pathways contributing resistance to IN inhibitors. We investigated the biochemical properties of these two mutants relative to SC assembly and their functional capabilities in the concerted integration assay. IN with the N155H mutation possessed ~70% capacity of wt IN for both SC assembly (Figure 6B and 6D) and concerted integration activity (Figure 6E) although, the kinetics of N155H for these events was slower (Figures 6). IN derived from HXB2-IIIB strain containing N155H substitution also possessed nearly two third of concerted integration activity compared to its wt counterpart (39). These data are consistent with ~70% replication capacity of HIV-1 containing this mutation compared to wt HIV-1 (7, 23, 24). In other studies with his-tag IN containing the N155H mutation, the catalytic activities using oligonucleotide DNA substrates demonstrated were ~5 to 35% relative to wt IN (45, 48, 49) suggesting, the presence of the tag or purification conditions affected the observed activities. An in-silico study of N155H and Q148H/R/K demonstrated that the structure of flexible loop (residues 140–148) in catalytic domain is conserved suggesting IN would be catalytically active (50). Comprehensive in vitro mutagenesis and computational studies of the flexible loop in HIV-1 IN accounted for most of the observed phenotypes of N155H and Q148H/R/K mutations in these RAL resistant viruses (51, 52). In our study, IN containing the Q148H mutation possessed nearly 30% activity for concerted integration relative to wt IN although it produced nearly 60–70% of CHS product compared to wt IN (Supporting Information, Figure S1). These data suggest the 3′-OH processing by IN having Q148H mutation was not severely affected under these assay conditions. The decreased yield of concerted integration products might be simply due to inefficient assembly of SC. We noted that formation of SC (data not shown) and STC (Figure 7B, lane 3 and 4) were delayed and inefficient relative to wt IN. In summary, the assembly properties for SC of IN containing N155H and Q148H mutations in vitro correlates with their replication capacities in vivo (7, 23, 24). Our results also demonstrated that IN carrying these RAL resistant mutations are functional in forming trapped SC at different capacities in vitro (Figure 7) as presumably observed in the PIC in vivo.

The N155H substitution provided varying degrees of cross-resistance to different STIs. The IC50 value for EVG with the N155H mutant to inhibit concerted integration was nearly 10-fold higher than wt IN (Figure 8C) similar to earlier studies using DNA oligonucleotides substrates (29, 45). An interesting observation was the susceptibility of N155H to MK-2048 and RDS 2197. MK-2048 had similar potency against wt IN and N155H with a low IC50 value of 42 nM for inhibiting concerted integration (Table 1). A plausible explanation for the effectiveness of MK-2048 could be the observed lower dissociation rate from IN-DNA complexes (53). The dissociation half-life of RAL with an N155H IN-DNA complex was nearly 0.7 h as compared to 7.3 h with wt IN-DNA complex. MK-2048 had a dissociation half-life of nearly 4 h and 32 h with N155H IN and wt IN, respectively (53). The relative longer half-life of MK-2048 in IN-DNA complexes could be a plausible reason for enhanced potency for inhibiting IN with the N155H mutation. Similar susceptibility (1.3 fold) of IN with the N155H mutation to RDS 2197 compared to wt IN to inhibit concerted integration was evident (Figure 8C)(Table 1). Further studies are necessary to fully understand the interactions of various STIs with resistant IN mutants that arise during drug therapies.

Scintillation proximity assays (SPA) have shown that STIs bind to IN-DNA complexes in a two-step binding mode and the inhibition of strand transfer is time-dependent (41, 42). Kinetic experiments with wt IN showed a time-dependent inhibition of concerted integration at a constant concentration of RAL (Figure 5A). At either 20 or 25 nM RAL, inhibition increased nearly ~3-fold from 30 min to 120 min. The initial 30 min point was used because assembly of SC is maximum at ~30 min with wt IN without inhibitor (Figure 6A, 6C) and slow 3′-OH processing is constantly occurring in SC with time (13, 15). Modeling and other studies of a STI bound to a IN-DNA complex revealed that a STI binding site become fully available only after the removal of 3′-GT nucleotides on the catalytic strand (34). Another study revealed that the terminal 3′-GT occupies the active site in closed conformation and the active site is left open immediately after 3′-processing and is accessible for binding STI (20, 42). Soaking of prototype foamy virus IN-DNA crystals containing 3′-OH recessed ends with RAL and EVG clearly demonstrated that these inhibitors occupied the active site of an IN tetramer resulting in the displacement of the 3′-OH recessed end (20).

During the suggested conformational change associated with 3′-OH processing in SC (16, 46), RAL binds to complexes with higher affinity resulting in the potent inhibition of concerted integration with increasing time (Figure 5A). In contrast, the above mentioned conformational changes may be different in IN-DNA complexes producing CHS products (Figure 5B). Initially using a U5 blunt-ended substrate, the IC50 values for all of the STIs to inhibit the insertion of a single DNA recessed end into supercoiled DNA is ~4 to 15-fold higher than observed with inhibition of concerted integration (Table 1). A single blunt-ended DNA molecule juxtaposed with a single 3′-OH recessed molecule within SC is sufficient for effective inhibition for L-870,810 with an IC50 value of ~60 nM while with two blunt-ended DNA molecules in SC, it is ~32 nM (39). These results suggest a possible cooperativity may exist between the IN subunits to bind STIs in SC which would be necessary for efficient inhibition of concerted integration (Figure 1).

This study suggests a correlation exists between the physical trapping of SC with the potency for inhibiting concerted integration using wt IN as well as N155H and Q148H. All of the STIs, irrespective of their chemical structures, bind to SC resulting in the accumulation of trapped SC. As suggested (53), a possible desired quality in second generation STIs may be a lower dissociation rate of a inhibitor from IN within the PIC. This enhanced association may more effectively block integration of wt HIV-1 as well as HIV-1 containing STI resistant IN mutants. In addition, inhibitors targeting regions of IN involved in binding cellular co-factors including the lens epithelium-derived growth factor (54, 55) and IN oligomerization (56) may be worth pursuing to combat drug resistance in the treatment of HIV/AIDS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Merck Research Laboratories for supplying MK-2048 and RAL. We also thank Drs. Yves Pommier and Christophe Marchand for a gift of EVG, RDS 1997, and RDS 2197 and Dr. Sapna Sinha for the comments on the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- HIV-1

human immunodeficiency virus

- IN

integrase

- LTR

long terminal repeat

- PIC

preintegration complex

- SC

synaptic complex

- H-SC

higher-order synaptic complex

- STC

strand transfer complex

- RAL

raltegravir

- EVG

elvitegravir

- STI

strand transfer inhibitor

- FS

full-site

- CHS

circular half-site

- D-D

donor-donor

- PIC

preintegration complex

- wt

wild-type

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant R21AI081629 and by Saint Louis University.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE

Supporting Information Figure S1. Concerted integration activity is reduced in Q148H. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Summa V, Petrocchi A, Bonelli F, Crescenzi B, Donghi M, Ferrara M, Fiore F, Gardelli C, Gonzalez Paz O, Hazuda DJ, Jones P, Kinzel O, Laufer R, Monteagudo E, Muraglia E, Nizi E, Orvieto F, Pace P, Pescatore G, Scarpelli R, Stillmock K, Witmer MV, Rowley M. Discovery of raltegravir, a potent, selective orally bioavailable HIV-integrase inhibitor for the treatment of HIV-AIDS infection. J Med Chem. 2008;51:5843–5855. doi: 10.1021/jm800245z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markowitz M, Morales-Ramirez JO, Nguyen BY, Kovacs CM, Steigbigel RT, Cooper DA, Liporace R, Schwartz R, Isaacs R, Gilde LR, Wenning L, Zhao J, Teppler H. Antiretroviral activity, pharmacokinetics, and tolerability of MK-0518, a novel inhibitor of HIV-1 integrase, dosed as monotherapy for 10 days in treatment-naive HIV-1-infected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:509–515. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802b4956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steigbigel RT, Cooper DA, Kumar PN, Eron JE, Schechter M, Markowitz M, Loutfy MR, Lennox JL, Gatell JM, Rockstroh JK, Katlama C, Yeni P, Lazzarin A, Clotet B, Zhao J, Chen J, Ryan DM, Rhodes RR, Killar JA, Gilde LR, Strohmaier KM, Meibohm AR, Miller MD, Hazuda DJ, Nessly ML, DiNubile MJ, Isaacs RD, Nguyen BY, Teppler H. Raltegravir with optimized background therapy for resistant HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:339–354. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lennox JL, DeJesus E, Lazzarin A, Pollard RB, Madruga JV, Berger DS, Zhao J, Xu X, Williams-Diaz A, Rodgers AJ, Barnard RJ, Miller MD, DiNubile MJ, Nguyen BY, Leavitt R, Sklar P. Safety and efficacy of raltegravir-based versus efavirenz-based combination therapy in treatment-naive patients with HIV-1 infection: a multicentre, double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:796–806. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60918-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ceccherini-Silberstein F, Malet I, D’Arrigo R, Antinori A, Marcelin AG, Perno CF. Characterization and structural analysis of HIV-1 integrase conservation. AIDS Rev. 2009;11:17–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper DA, Steigbigel RT, Gatell JM, Rockstroh JK, Katlama C, Yeni P, Lazzarin A, Clotet B, Kumar PN, Eron JE, Schechter M, Markowitz M, Loutfy MR, Lennox JL, Zhao J, Chen J, Ryan DM, Rhodes RR, Killar JA, Gilde LR, Strohmaier KM, Meibohm AR, Miller MD, Hazuda DJ, Nessly ML, DiNubile MJ, Isaacs RD, Teppler H, Nguyen BY. Subgroup and resistance analyses of raltegravir for resistant HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:355–365. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fransen S, Gupta S, Danovich R, Hazuda D, Miller M, Witmer M, Petropoulos CJ, Huang W. Loss of raltegravir susceptibility by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is conferred by multiple non-overlapping genetic pathways. J Virol. 2009;83:11440–11446. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01168-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fransen S, Karmochkine M, Huang W, Weiss L, Petropoulos CJ, Charpentier C. Longitudinal analysis of raltegravir susceptibility and integrase replication capacity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 during virologic failure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4522–4524. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00651-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goethals O, Clayton R, Van Ginderen M, Vereycken I, Wagemans E, Geluykens P, Dockx K, Strijbos R, Smits V, Vos A, Meersseman G, Jochmans D, Vermeire K, Schols D, Hallenberger S, Hertogs K. Resistance mutations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase selected with elvitegravir confer reduced susceptibility to a wide range of integrase inhibitors. J Virol. 2008;82:10366–10374. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00470-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McColl DJ, Fransen S, Gupta S, Parkin N, Margot N, Chuck S, Cheng AK, Miller MD. Resistance and cross-resistance to first generation integrase inhibitors: insights from a Phase II study of elvitegravir (GS 9137). XVI International Drug Resistance Workshop; Barbados West Indies. 2007. p. S11. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimura K, Kodama E, Sakagami Y, Matsuzaki Y, Watanabe W, Yamataka K, Watanabe Y, Ohata Y, Doi S, Sato M, Kano M, Ikeda S, Matsuoka M. Broad antiretroviral activity and resistance profile of the novel human immunodeficiency virus integrase inhibitor elvitegravir (JTK-303/GS-9137) J Virol. 2008;82:764–774. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01534-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wirden M, Simon A, Schneider L, Tubiana R, Malet I, Ait-Mohand H, Peytavin G, Katlama C, Calvez V, Marcelin AG. Raltegravir has no residual antiviral activity in vivo against HIV-1 with resistance-associated mutations to this drug. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64:1087–1090. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pandey KK, Bera S, Zahm J, Vora A, Stillmock K, Hazuda D, Grandgenett DP. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 concerted integration by strand transfer inhibitors which recognize a transient structural intermediate. J Virol. 2007;81:12189–12199. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02863-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li M, Mizuuchi M, Burke TR, Jr, Craigie R. Retroviral DNA integration: reaction pathway and critical intermediates. EMBO J. 2006;25:1295–1304. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bera S, Pandey KK, Vora AC, Grandgenett DP. Molecular interactions between HIV-1 integrase and the two viral DNA ends within the synaptic complex that mediates concerted integration. J Mol Biol. 2009;389:183–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pandey KK, Grandgenett DP. HIV-1 integrase strand transfer inhibitors: Novel insights into their mechanism of action. Retrovirology: Research and Treatment. 2008;2:11–16. doi: 10.4137/rrt.s1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pandey KK, Sinha S, Grandgenett DP. Transcriptional coactivator LEDGF/p75 modulates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase-mediated concerted integration. J Virol. 2007;81:3969–3979. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02322-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li M, Craigie R. Nucleoprotein complex intermediates in HIV-1 integration. Methods. 2009;47:237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faure A, Calmels C, Desjobert C, Castroviejo M, Caumont-Sarcos A, Tarrago-Litvak L, Litvak S, Parissi V. HIV-1 integrase crosslinked oligomers are active in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:977–986. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hare S, Gupta SS, Valkov E, Engelman A, Cherepanov P. Retroviral intasome assembly and inhibition of DNA strand transfer. Nature. 2010;464:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature08784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hazuda DJ, Anthony NJ, Gomez RP, Jolly SM, Wai JS, Zhuang L, Fisher TE, Embrey M, Guare JP, Jr, Egbertson MS, Vacca JP, Huff JR, Felock PJ, Witmer MV, Stillmock KA, Danovich R, Grobler J, Miller MD, Espeseth AS, Jin L, Chen IW, Lin JH, Kassahun K, Ellis JD, Wong BK, Xu W, Pearson PG, Schleif WA, Cortese R, Emini E, Summa V, Holloway MK, Young SD. A naphthyridine carboxamide provides evidence for discordant resistance between mechanistically identical inhibitors of HIV-1 integrase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11233–11238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402357101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hazuda DJ, Felock P, Witmer M, Wolfe A, Stillmock K, Grobler JA, Espeseth A, Gabryelski L, Schleif W, Blau C, Miller MD. Inhibitors of strand transfer that prevent integration and inhibit HIV-1 replication in cells. Science. 2000;287:646–650. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Witmer M, Danovich R. Selection and analysis of HIV-1 integrase strand transfer inhibitor resistant mutant viruses. Methods. 2009;47:277–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delelis O, Malet I, Na L, Tchertanov L, Calvez V, Marcelin AG, Subra F, Deprez E, Mouscadet JF. The G140S mutation in HIV integrases from raltegravir-resistant patients rescues catalytic defect due to the resistance Q148H mutation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1193–1201. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cherepanov P, Surratt D, Toelen J, Pluymers W, Griffith J, De Clercq E, Debyser Z. Activity of recombinant HIV-1 integrase on mini-HIV DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2202–2210. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.10.2202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sinha S, Pursley MH, Grandgenett DP. Efficient concerted integration by recombinant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase without cellular or viral cofactors. J Virol. 2002;76:3105–3113. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.7.3105-3113.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grandgenett DP, Bera S, Pandey KK, Vora AC, Zahm J, Sinha S. Biochemical and biophysical analyses of concerted (U5/U3) integration. Methods. 2009;47:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vacca J, Wai J, Fisher T, Embrey M, Hazuda D, Miller M, Felock P, Witmer M, Gabryelski L, Lyle T. Discovery of MK-2048 - subtle changes confer unique resistance properties to a series of tricyclic hydroxypyrrole integrase strand transfer inhibitors. 4th International AIDS Society (IAS) Conference; July 22–25, 2007; Sydney Australia. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wai J, Fisher T, Embrey M, Egbertson M, Vacca J, Hazuda D, Miller M, Witmer L, Gabryelski L, Lyle T. Next generation of inhibitors of HIV-1 integrase strand transfer inhibitor: structural diversity and resistance profiles. 14th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Feb 25–28, 2007; Los Angeles CA. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sato M, Motomura T, Aramaki H, Matsuda T, Yamashita M, Ito Y, Kawakami H, Matsuzaki Y, Watanabe W, Yamataka K, Ikeda S, Kodama E, Matsuoka M, Shinkai H. Novel HIV-1 integrase inhibitors derived from quinolone antibiotics. J Med Chem. 2006;49:1506–1508. doi: 10.1021/jm0600139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Di Santo R, Costi R, Roux A, Artico M, Lavecchia A, Marinelli L, Novellino E, Palmisano L, Andreotti M, Amici R, Galluzzo CM, Nencioni L, Palamara AT, Pommier Y, Marchand C. Novel bifunctional quinolonyl diketo acid derivatives as HIV-1 integrase inhibitors: design, synthesis, biological activities, and mechanism of action. J Med Chem. 2006;49:1939–1945. doi: 10.1021/jm0511583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Santo R, Costi R, Roux A, Miele G, Crucitti GC, Iacovo A, Rosi F, Lavecchia A, Marinelli L, Di Giovanni C, Novellino E, Palmisano L, Andreotti M, Amici R, Galluzzo CM, Nencioni L, Palamara AT, Pommier Y, Marchand C. Novel quinolinonyl diketo acid derivatives as HIV-1 integrase inhibitors: design, synthesis, and biological activities. J Med Chem. 2008;51:4744–4750. doi: 10.1021/jm8001422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sinha S, Grandgenett DP. Recombinant HIV-1 integrase exhibits a capacity for full-site integration in vitro that is comparable to that of purified preintegration complexes from virus-infected cells. J Virol. 2005;79:8208–8216. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8208-8216.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen X, Tsiang M, Yu F, Hung M, Jones GS, Zeynalzadegan A, Qi X, Jin H, Kim CU, Swaminathan S, Chen JM. Modeling, analysis, and validation of a novel HIV integrase structure provide insights into the binding modes of potent integrase inhibitors. J Mol Biol. 2008;380:504–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Svarovskaia ES, Barr R, Zhang X, Pais GC, Marchand C, Pommier Y, Burke TR, Jr, Pathak VK. Azido-containing diketo acid derivatives inhibit human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase in vivo and influence the frequency of deletions at two-long-terminal-repeat-circle junctions. J Virol. 2004;78:3210–3222. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3210-3222.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goffinet C, Allespach I, Oberbremer L, Golden PL, Foster SA, Johns BA, Weatherhead JG, Novick SJ, Chiswell KE, Garvey EP, Keppler OT. Pharmacovirological impact of an integrase inhibitor on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cDNA species in vivo. J Virol. 2009;83:7706–7717. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00683-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Delelis O, Thierry S, Subra F, Simon F, Malet I, Alloui C, Sayon S, Calvez V, Deprez E, Marcelin AG, Tchertanov L, Mouscadet JF. Impact of Y143 HIV-1 integrase mutations on resistance to raltegravir in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:491–501. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01075-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grandgenett DP, Inman RB, Vora AC, Fitzgerald ML. Comparison of DNA binding and integration half-site selection by avian myeloblastosis virus integrase. J Virol. 1993;67:2628–2636. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2628-2636.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zahm JA, Bera S, Pandey KK, Vora A, Stillmock K, Hazuda D, Grandgenett DP. Mechanisms of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 concerted integration related to strand transfer inhibition and drug resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3358–3368. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00271-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen H, Wei SQ, Engelman A. Multiple integrase functions are required to form the native structure of the human immunodeficiency virus type I intasome. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17358–17364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.17358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garvey EP, Schwartz B, Gartland MJ, Lang S, Halsey W, Sathe G, Carter HL, Weaver KL. Potent inhibitors of HIV-1 integrase display a two-step, slow-binding inhibition mechanism which is absent in a drug-resistant T66I/M154I mutant. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1644–1653. doi: 10.1021/bi802141y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Langley DR, Samanta HK, Lin Z, Walker MA, Krystal MR, Dicker IB. The terminal (catalytic) adenosine of the HIV LTR controls the kinetics of binding and dissociation of HIV integrase strand transfer inhibitors. Biochemistry. 2008;47:13481–13488. doi: 10.1021/bi801372d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Copeland RA. Slow binding inhibitors. In: Copeland RA, editor. Evaluation of enzyme inhibitors in drug discovery. Wiley-Interscience; 2005. pp. 141–177. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson AA, Santos W, Pais GC, Marchand C, Amin R, Burke TR, Jr, Verdine G, Pommier Y. HIV-1 integration requires the viral DNA end (5′-C) interaction with glutamine 148 of the integrase flexible loop. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:461–467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511348200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marinello J, Marchand C, Mott BT, Bain A, Thomas CJ, Pommier Y. Comparison of raltegravir and elvitegravir on HIV-1 integrase catalytic reactions and on a series of drug-resistant integrase mutants. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9345–9354. doi: 10.1021/bi800791q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pommier Y, Johnson AA, Marchand C. Integrase inhibitors to treat HIV/AIDS. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:236–248. doi: 10.1038/nrd1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pommier Y, Marchand C. Interfacial inhibitors of protein-nucleic acid interactions. Curr Med Chem Anticancer Agents. 2005;5:421–429. doi: 10.2174/1568011054222337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dicker IB, Terry B, Lin Z, Li Z, Bollini S, Samanta HK, Gali V, Walker MA, Krystal MR. Biochemical analysis of HIV-1 integrase variants resistant to strand transfer inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:23599–23609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804213200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malet I, Delelis O, Valantin MA, Montes B, Soulie C, Wirden M, Tchertanova L, Peytavin G, Reynes J, Mouscadet JF, Katlama C, Calvez V, Marcelin AG. Mutations associated with failure of raltegravir treatment affect integrase sensitivity to the inhibitor in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1351–1358. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01228-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mouscadet JF, Arora R, Andre J, Lambry JC, Delelis O, Malet I, Marcelin AG, Calvez V, Tchertanov L. HIV-1 IN alternative molecular recognition of DNA induced by raltegravir resistance mutations. J Mol Recognit. 2009;22:480–494. doi: 10.1002/jmr.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mouscadet JF, Delelis O, Marcelin AG, Tchertanov L. Resistance to HIV-1 integrase inhibitors: A structural perspective. Drug Resist Updat. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2010.05.001. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Metifiot M, Maddali K, Naumova A, Zhang X, Marchand C, Pommier Y. Biochemical and pharmacological analyses of HIV-1 integrase flexible loop mutants resistant to raltegravir. Biochemistry. 2010;49:3715–3722. doi: 10.1021/bi100130f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grobler JA, McKemma PM, Ly S, et al. Functionally irreversible inhibition of integration by slowly dissociating strand transfer inhibitors. 10th International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV Therapy; Amsterdam. 2009. Abstract O-10. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Engelman A, Cherepanov P. The lentiviral integrase binding protein LEDGF/p75 and HIV-1 replication. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000046. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hare S, Cherepanov P. The interaction between lentiviral integrase and LEDGF: structural and functional insights. Viruses. 2009;1:780–801. doi: 10.3390/v1030780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kessl J, McKee C, Eidahl J, Shkriabai N, Katz A, Kvaratskhelia M. HIV-1 integrase-DNA recognition mechanisms. Viruses. 2009;1:713–736. doi: 10.3390/v1030713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.