Abstract

Regulation of the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin by tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA) is critical in the control of fibrin deposition. While several plasminogen activators have been described, soluble plasma cofactors that stimulate fibrinolysis have not been characterized. Here, we report that the abundant plasma glycoprotein, β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI), stimulates t-PA–dependent plasminogen activation in the fluid phase and within a fibrin gel. The region within β2GPI responsible for stimulating t-PA activity is at least partially contained within β2GPI domain V. β2GPI bound t-PA with high affinity (Kd ~ 20 nM), stimulated t-PA amidolytic activity, and caused an overall 20-fold increase in the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) of t-PA–mediated conversion of Glu-plasminogen to plasmin. Moreover, depletion of β2GPI from plasma led to diminished rates of clot lysis, with restoration of normal lysis rates following β2GPI repletion. Finally, stimulation of t-PA–mediated plasminogen activity by β2GPI was inhibited by monoclonal anti-β2GPI antibodies, as well as by anti-β2GPI antibodies from patients with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). These findings suggest that β2GPI may be an endogenous regulator of fibrinolysis. Impairment of β2GPI-stimulated fibrinolysis by anti-β2GPI antibodies may contribute to the development of thrombosis in patients with APS.

Keywords: β2-glycoprotein I, t-PA, plasminogen, antiphospholipid, fibrinolysis

Introduction

β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI) belongs to the complement control (CCP) superfamily and circulates in plasma at a concentration of ~ 4μM (1). Like other CCP superfamily members, which contain one or more characteristic short consensus repeats (SCR)(2), β2GPI contains five SCRs. However, domain V of β2GPI consists of an atypical SCR containing a lysine-rich sequence (CKNKEKKC) that imparts a positive charge to this domain and mediates the binding of β2GPI to phospholipid (3). Plasmin cleavage between Lys317-Thr318 of β2GPI domain 5 abolishes phospholipid binding (4). β2GPI is an important antigen in the antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), and anti-β2GPI antibodies are an independent risk factor for thrombosis and recurrent pregnancy loss (5–7). β2GPI may regulate both procoagulant and anticoagulant activities (7–9). Thrombin generation is impaired in the plasma of β2GPI-deficient mice (10).

Impaired fibrinolysis may contribute to the development of thrombosis (11;12). Plasmin plays a central role in lysis of fibrin thrombi, and the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin by tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA) and urokinase-type plasminogen activator (u-PA) is precisely regulated (13). t-PA binds fibrin with high affinity and may be of particular importance for lysis of fibrin thrombi in the vasculature (13). Several stimulators of fibrinolysis, including insoluble proteins, protein aggregates, microfilaments, fibrin fragments, or collagen IV may stimulate fibrinolysis, primarily by promoting formation of a ternary t-PA–fibrin–plasminogen complex (14;15). Annexin A2 is an endothelial cell co-receptor for plasminogen and t-PA that accelerates t-PA–dependent plasminogen activation (16;17), and the annexin A2/S100A10 heterotetramer may be even more potent in this regard (18–20). However, to date there have been no soluble plasma cofactors identified that promote t-PA-dependent plasminogen activation.

Several studies have examined interactions of β2GPI with the fibrinolytic system. Lopez-Lira et al (21) and Yasuda et al (22) reported low affinity binding of Glu-plasminogen to intact, or plasmin-cleaved β2GPI, respectively. However, interactions of β2GPI with t-PA have not been described. Here, we report that β2GPI binds t-PA with high affinity, and enhances t-PA activity and t-PA–dependent plasminogen activation. Depletion of β2GPI from plasma impairs the lysis of plasma clots, and anti-β2GPI antibodies inhibit the ability of β2GPI to stimulate fibrinolysis. Given the abundance of β2GPI in plasma, these findings suggest that β2GPI may be an endogenous regulator of fibrinolysis, and that impairment of fibrinolysis by anti-β2GPI antibodies may contribute to APS-associated thrombosis.

Materials and methods

Purification of β2GPI from human plasma

β2GPI was purified from human plasma using a modification of previously described methods (23). Briefly, polyethylene glycol (final concentration 15%) was added to plasma, and the precipitated proteins were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 × G for 30 minutes. The precipitate was resuspended, and β2GPI was isolated by sequential chromatography using heparin-Sepharose CL-6B (Sterogene Bioseparations Inc., Carlsbad, CA) and Source 15S (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). The purity of isolated β2GPI was confirmed using 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

Cloning, expression and purification of β2GPI in mammalian cells

Full length β2GPI cDNA was cloned into pDNR-LIB (Sanying Biotechnology, Beijing, China). For expression of recombinant β2GPI, the β2GPI coding sequence was amplified using the primers 5′ C ACC ATG GGA CGG ACC TGT CCC AAG 3′ and 5′GCA TGG CTT TAC ATC GGA TGC ATC A 3′ (24) and cloned into pcDNA3.1. β2GPI-pcDNA3.1 was transfected into 293-T cells, and cell extracts prepared 48 hours after transfection were analyzed by immunoblotting using rabbit anti-human β2GPI and anti-His (C-terminal) antibodies. The 6× His-tagged recombinant β2GPI was purified using Ni-NTA superflow columns (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech).

Preparation of recombinant β2GPI domain V

The sequence encoding β2GPI domain V (β2GPI-V) was amplified from β2GPI-pDNR-LIB using the primers 5′ CAC GGA TCC AAA GCA TCT TGT AAA GTA CC 3′ and 5′ CTG AAG CTT TTA GCA TGG CTT TAC ATC 3′, and the PCR product cloned into vector PQE30 (ZH Xie, Tsinghua University) using Bam HI and Hind III restriction sites (underlined). The domain V construct was transfected into competent E. coli M15 cells grown in 100 μg/mL ampicillin and 25 μg/mL kanamycin, and expression was induced by exposure of cells to 1 mM IPTG at 37°C for 4 hours. The 6× His-tagged β2GPI-V was purified using Ni-NTA superflow, and the purity of the recombinant polypeptide was confirmed using 15% SDS-PAGE.

A domain V peptide corresponding to amino acids Gly274-Cys288 (GQKVSFFCKNKEKKC) of β2GPI was synthesized by Eurogentec (San Diego, CA).

Monoclonal anti-β2GPI antibodies

The monoclonal anti-β2GPI antibody BD4 was raised against intact β2GPI, using standard methods (25). This antibody had an affinity constant for β2GPI of 2.04 × 107M−1. Murine IgG1 monoclonal antibody 1D2, also raised against intact β2GPI, was obtained from ABCAM (Cambridge, UK). The epitopes for these antibodies have not been defined. Both antibodies are of the IgG1 subclass.

The effect of β2GPI on t-PA-dependent plasminogen activation

The effect of β2GPI on t-PA-dependent plasminogen activation was measured using a fluorogenic plasmin substrate (I-1390, H-D-Val-Leu-Lys-AMC; Bachem Bioscience, King of Prussia, PA). Briefly, 10 nM t-PA was incubated with increasing concentrations of native or recombinant β2GPI, β2GPI-V, β2GPI domain V peptide, or 0.5% BSA (as a control) at room temperature for 15 minutes. Fifty microliters of each reaction mixture was then transferred to 96-well microplates, to which 100 nM Glu-plasminogen (Enzyme Research Laboratories, South Bend IN) and 200 μM H-D-Val-Leu-Lys-AMC was added. After mixing, substrate hydrolysis was measured at regular intervals as relative fluorescence units (I360/465 nm). Initial rates of plasmin generation were determined by linear regression analysis of plots of I360/465 nm versus time2 using Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) (17).

Parallel studies were performed using an identical approach, but substituting urokinase-type plasminogen activator (u-PA) for t-PA.

The effect of β2GPI on t-PA-dependent plasminogen activation in a fibrin gel

Fibrin-agarose gels were prepared by mixing 4 mL of agarose (1%, 55° C), 4 mL fibrinogen (3 mg/mL), 320 μL Glu-plasminogen (500 nM) and 320 μL thrombin (1 U/ml) in 10 mL polypropylene tubes. The contents of each tube were added to 90 mm plates and allowed to gel. After incubation at 4 C for 1 hour, 10 μl of reaction mixtures containing 10 nM t-PA alone or in the presence of β2GPI, β2GPI-V, β2GPI domain V peptide or 0.5% BSA, were placed in individual wells prepared in the gels using glass pipettes. After 28 hours at 37 C, the area of lysis caused by each sample was measured.

Effect of plasma β2GPI depletion on clot lysis

The fibrinolytic activity of control and β2GPI-depleted plasma from three normal donors was compared. First, rabbit preimmune or anti-human β2GPI IgG was conjugated to Affigel-10 (Bio-Rad) at a concentration of 5 mg IgG per ml of beads. The beads were placed in separate columns, and 2 ml of plasma was passed through each. β2GPI was not detectable by immunoblotting of plasma passed through the anti-β2GPI column, and the first 1 ml flow-through fraction from this column was used for subsequent studies. The corresponding flow-through fraction from the column containing preimmune IgG was used as a control.

The fibrinolytic activity of control and β2GPI-depleted plasma was determined using a 96-well microplate clot lysis assay described by Nagashima et al (26). Briefly, 15 μl of β2GPI-depleted or control plasma was mixed with 3 μl of 2 μM thrombomodulin and 60 μl of 0.04 M HEPES, pH 7.0, containing 0.15 M NaCl and 0.01% Tween-80. This mixture was added to another well containing 4 μl of 75 U/ml thrombin, 2 μl of 1 M CaCl2 and 4 μl of 0.5 μg/ml t-PA. The total volume was adjusted to 120 μl with water. The absorbance of the clotted sample at 405 nm (A405) was monitored every 15 minutes for 180 minutes. Maximal absorbance occurred at 30 minutes, and the extent of lysis was defined as the difference between A405 at 30 minutes (T = 30), and 180 minutes (T = 180).

To confirm that any difference in clot lysis between control and β2GPI-depleted plasmas was actually due to β2GPI depletion, a β2GPI-depleted plasma sample was replenished with 100 nM or 200 nM (final concentrations) purified human β2GPI. Clot lysis rates were then determined using the protocol described in the preceding paragraph.

The effect of β2GPI on t-PA amidolytic activity

t-PA activity was determined in the absence or presence of β2GPI using a fluorogenic t-PA substrate (I-1195, Glutaryl-Gly-Arg-AMC; Bachem). Assays were performed in 96-well plates containing mixtures of t-PA (10 nM) and increasing concentrations of β2GPI (0–5 μM), or 0.5% BSA. Reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes, at which point 200 μM I-1195 was added and substrate hydrolysis measured at regular intervals (I360/465 nm). Initial rates of hydrolysis were calculated by linear regression of plots of I360/465 nm versus time2 (K) using Prism 4.0 (17).

Binding of β2GPI to t-PA

Binding of β2GPI to t-PA was initially analyzed using a microplate binding assay. High-binding ELISA plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA) were coated with 10 μg/mL single chain t-PA by overnight incubation at 4° C. After washing, wells were incubated with 100 μL of increasing concentrations of β2GPI at 25° C for 4 hours. Bound β2GPI was detected using rabbit anti-human β2GPI (0.33 μg/mL) followed by peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and tetramethylbenzidine. Binding specificity was determined by assessing the ability of fluid phase t-PA to inhibit the binding of 40 nM β2GPI.

We also analyzed the binding of β2GPI to t-PA in real time using an IAsys plus biosensor system (Affinity Sensors, Paramus, NJ). β2GPI was immobilized on a carboxymethyl dextran biosensor using amine coupling, and the amount of ligand bound to the β2GPI-coated surface was assessed following injection of t-PA(0–14 nM). Iasys FASTfit software was used to determine the association and dissociation rate constant (Kass and Kdiss). The binding of plasminogen to β2GPI was assessed using an identical approach.

Anti-β2GPI antibodies inhibit plasminogen activation

IgG fractions were purified from 83 plasma samples (supplied by the Guangdong Family Planning Science and Technology Institute) using protein G agarose. These samples were from 40 healthy controls and 43 patients who met Sapporo criteria for definite APS (27). The 43 patients with APS were positive for either IgG/M anticardiolipin antibody (aCL) (32 patients), IgG/M anti-β2-glycoprotein 1 (β2GP1) antibody (24 patients), and/or or lupus anticoagulant (LA) (11 patients). Twenty-two samples contained anti-β2GPI but not anti-tPA antibodies, while 21 APS samples contained neither anti-β2GPI nor anti-tPA antibodies.

We also assessed the effect of affinity-purified anti-β2GPI antibodies, isolated from patient plasma as we have previously described (28), on the ability of β2GPI to enhance t-PA-mediated plasminogen activation.

The effect of anti-β2GPI antibodies on β2GPI-dependent enhancement of plasminogen activation was determined by measuring plasmin amidolytic activity following incubation of plasminogen with t-PA and β2GPI in the absence or presence of monoclonal anti-β2GPI antibodies, patient-derived anti-β2GPI+/anti-tPA− or anti-β2GPI−/anti-tPA− IgG fractions or affinity-purified anti-β2GPI IgG. Initial rates of plasmin generation were calculated by linear regression analysis of plots of I360/465 nm versus time2 using Prism® 4.0.

Statistical analysis

Stastical analyses were performed using the Student’s two-tailed T-test or the Mann-Whitney U test. A P value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

β2GPI stimulates t-PA-mediated plasminogen activation

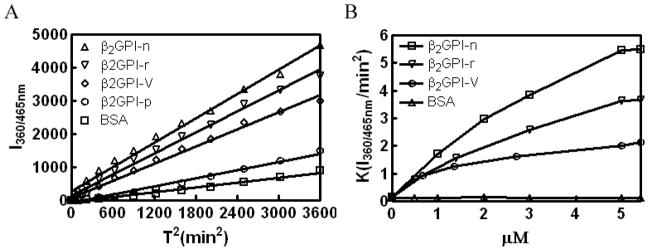

Native β2GPI (β2GPI-n), recombinant β2GPI (β2GPI-r), and β2GPI domain V (β2GPI-V) accelerated the initial rate of plasminogen activation by t-PA in a concentration-dependent manner, as measured by cleavage of the plasmin substrate H-D-Val-Leu-Lys-AMC (Figure 1A, B). In contrast, the β2GPI domain V peptide GQKVSFFCKNKEKKC did not significantly enhance plasminogen activation (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. β2GPI enhances t-PA–dependent Glu-plasminogen activation.

(A) t-PA-dependent plasminogen activation was measured either alone (in the presence of BSA) or in the presence of 1 μM human β2GPI (β2GPI-n), recombinant β2GPI (β2GPI-r), β2GPI domain V (β2GPI-V), or β2GPI domain V peptide (β2GPI-p). Substrate hydrolysis was measured as relative fluorescence units (I360/465 nm) as a function of time2 (T)2 (37). (B) Initial rates of plasmin generation were determined as in (A) in the presence of increasing concentrations of β2GPI-n, β2GPI-r, β2GPI-V, or BSA.

β2GPI was similarly effective when a fixed concentration of t-PA (10 nM) was employed to activate increasing concentrations of plasminogen (0–200 nM). Analysis of this data using Lineweaver-Burke plots revealed that β2GPI and β2GPI domain V conferred a 19.7-fold and 5.9-fold increase, respectively, in the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) of t-PA–mediated glu-plasminogen activation (Table 1). The observed increase in catalytic efficiency resulted from a decrease in the Km (9.8-fold) and enhancement of Vmax (2-fold). By comparison, Cesarman et al (17) reported that annexin A2 caused a 63-fold increase in the catalytic efficiency of t-PA-mediated Glu-plasminogen activation, reflecting a 9-fold decrease in the Km and a 5-fold increase in Vmax (17).

Table 1.

Effects of native β2GPI and β2GPI domain V kinetics of t-PA–dependent activation of Glu-plasminogen*

| Km (μM) | Kcat (s−1) | Kcat/Km (μM−1s−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasminogen + BSA | 0.4538 | 0.1149 | 0.253 |

| Plasminogen + β2GPI | 0.0464 | 0.2310 | 4.983 |

| Plasminogen + β2GPI-V | 0.3148 | 0.4718 | 1.499 |

Vmax and Km were calculated using nonlinear regression. kcat was calculated as Vmax/E0, where E0 represents the t-PA concentration (10 nM). Vmax was derived from a standard curve of plasmin amidolytic activity.

Neither human albumin nor control human IgG affected t-PA-dependent plasminogen activation. Parallel studies demonstrated that β2GPI did not affect the ability of single-chain urokinase to activate plasminogen.

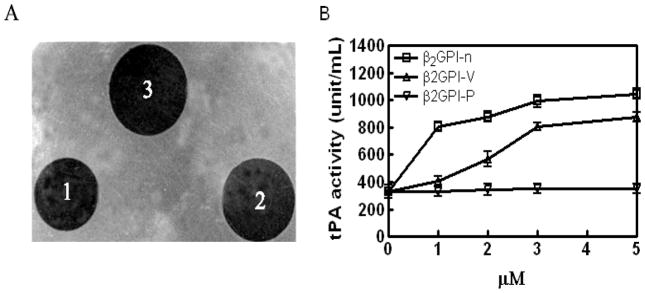

β2GPI stimulates fibrinolysis in a fibrin gel

β2GPI caused a 2.6 and 3.1-fold increase in lysis of a fibrin gel at concentrations of 1 μM and 5 μM, respectively (Figure 2).β2GPI-V (5 μM) caused 2.6-fold stimulation of fibrinolysis, though the Gly274-Cys288 β2GPI-V peptide had no effect. Control proteins, BSA and IgG, also had no activity. While the relative amount of fibrin digestion in this assay seems proportionally small compared to the extent of plasminogen activation in amidolytic assays, the kinetic parameters governing these assays are not comparable.

Figure 2. Native β2GPI and β2GPI domain V enhance fibrinolysis in fibrin gels.

Lysis of fibrin gels was assessed as described in Materials and Methods. (A) A representative experiment: (1) 10 nM t-PA + BSA; (2) 10 nM t-PA + 5 μM β2GPI-V; (3) 10 nM t-PA + 5 μM native β2GPI. (B) t-PA activity (U/ml) (as determined from the size of lytic areas) in the absence or presence of increasing amounts of native β2GPI-n, β2GPI-V, or β2GPI peptide (β2GPI-p), calculated from a standard curve.

Effect of plasma β2GPI depletion on clot lysis

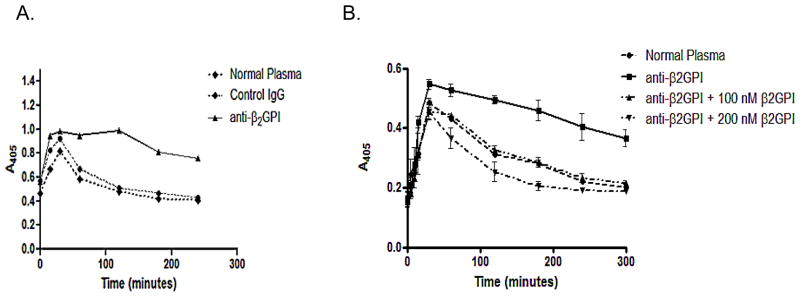

Plasma that had been perfused over an anti-β2GPI column contained no immunologically-detectable β2GPI, as determined by immunoblotting (not shown). Plasma from the same donors was perfused over a column containing preimmune (control) rabbit IgG, to control for dilution. Both plasma samples were clotted and their clot lysis rates determined as described in Materials and Methods.

Table 2 depicts the extent of clot lysis using control and β2GPI-depleted plasma from three donors. Though the maximal A405 and extent of lysis varied, the decrease in absorbance between 30 and 180 minutes, reflecting clot lysis (26), was significantly diminished in the absence of β2GPI (P = 0.0260 when comparing the means of triplicate points).

Table 2.

Effect of β2GPI depletion on clot lysis

| A405 (T = 30) | A405 (T = 180) | ΔA405 | % lysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt 1 | Anti-β2GPI | .595 | .509 | .086 | 14.4 |

| Control IgG | .368 | .204 | .164 | 44.5 | |

| Pt 2 | Anti-β2GPI | 1.09 | .81 | .28 | 25.6 |

| Control IgG | .92 | .47 | .45 | 48.9 | |

| Pt 3 | Anti-β2GPI | 1.29 | 1.30 | −0.01 | 0 |

| Control IgG | 1.19 | .70 | .49 | 41.1 |

Figure 3A depicts a representative experiment in which endogenous clot lysis rates in control and β2GPI-depleted plasma is compared. Figure 3B demonstrates that the reconstitution of β2GPI-depleted plasma with purified β2GPI (100 and 200 nM final concentrations) led to complete restoration of lytic activity in the β2GPI-depleted plasmas.

Figure 3. Clot formation and lysis in the absence and presence of β2GPI.

(A) Plasma from a normal donor was divided into equal aliquots and subjected to chromatography on a column to which either anti-β2GPI antibodies or preimmune-rabbit IgG had been conjugated. After passing through the former column, plasma was completely immunodepleted of β2GPI as determined by immunoblotting. The flow-through from both columns was placed in 96 well microplates and clotted as described in Materials and Methods. Clots were monitored by measurement of A405. Clotting led to an increase in A405 which was maximal at approximately 30 minutes, followed by a progressive decrease as clots lysed. Normal plasma (black diamonds) did not undergo chromatography. (B) The identical experiment as depicted in (A) was performed, but β2GPI-depleted plasma was analyzed either directly (squares, solid lines) or after the addition of 100 μM β2GPI (triangles) or 200 μM β2GPI (inverted triangles). The addition of β2GPI to the β2GPI-depleted plasma restored its fibrinolytic activity.

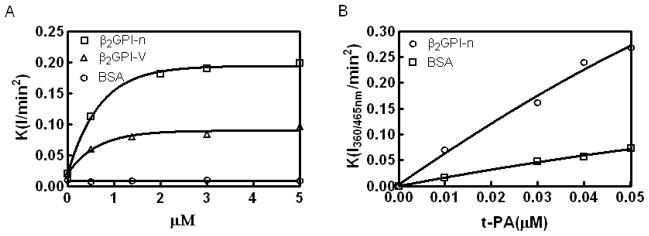

β2GPI stimulates t-PA amidolytic activity

β2GPI enhanced the t-PA-dependent cleavage of I-1105, a t-PA specific substrate, in a concentration-dependent manner. A concentration of 0.3 μM β2GPI caused a 4-fold increase in the rate of substrate hydrolysis (Figure 4A). A stimulatory effect of β2GPI (1 μM) was also observed in the presence of increasing concentrations of t-PA (0–50 nM) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. β2GPI stimulates t-PA amidolytic activity.

(A) t-PA amidolytic activity in the presence of increasing amounts of native β2GPI and β2GPI domain V. (B) The effect of 1 μMβ2GPI on t-PA amidolytic activity in the presence of increasing concentrations of t-PA.

β2GPI binds to t-PA

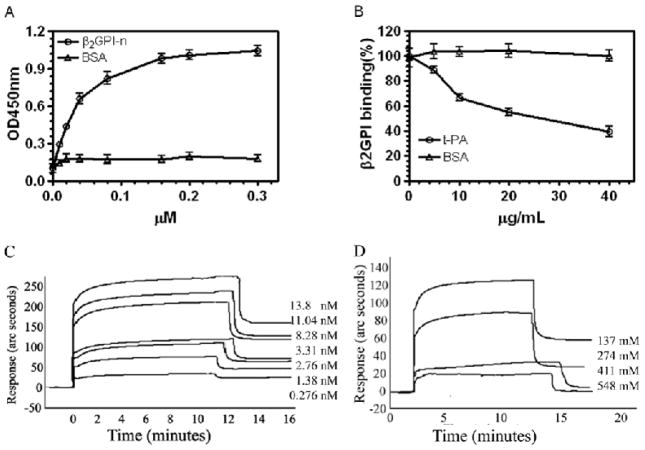

β2GPI bound to t-PA–coated microplates in a concentration dependent manner (Figure A) that was competitively inhibited by fluid phase t-PA (IC50 ~ 310 nM) (Figure 5B). Binding was not inhibited by the β2GPI domain V-derived peptide (Gly274-Cys288) previously reported to mediate the binding ofβ2GPI to anionic phospholipid (not shown), suggesting that different molecular interactions facilitate these binding events.

Figure 5. Binding of β2GPI to t-PA.

(A) Binding of β2GPI to t-PA using a microplate assay was performed as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Inhibition of the binding of 40 nM β2GPI to immobilized t-PA by fluid phase t-PA. β2GPI binding is expressed as the percentage of β2GPI bound in the presence of fluid-phase t-PA relative to that bound in its absence. (C) Binding of t-PA to β2GPI using an optical biosensor. The concentration of t-PA used is depicted to the right of the curve. (D) Binding of t-PA to β2GPI was inhibited by increasing concentrations of NaCl.

Optical biosensor analysis confirmed a specific interaction between β2GPI and t-PA (Figure 5C). Analysis of real time binding curves yielded a Kass as 1.13 ± 0.07 × 105 M−1S−1 and Kdiss as 6.19 ± 0.10 × 10−3 S−1. Accordingly, KD and KA were determined to be 2.0 × 10−8 M and 5.0 × 107 M−1, respectively.

We observed only weak binding between Glu-plasminogen and intact β2GPI (KD > 1 μM) using the same optical biosensor system (not shown), consistent with the findings of Lopez-Lira et al (21).

High concentrations of NaCl inhibited the binding between β2GPI and t-PA, suggesting a strong ionic component to the binding interaction (Figure 5D).

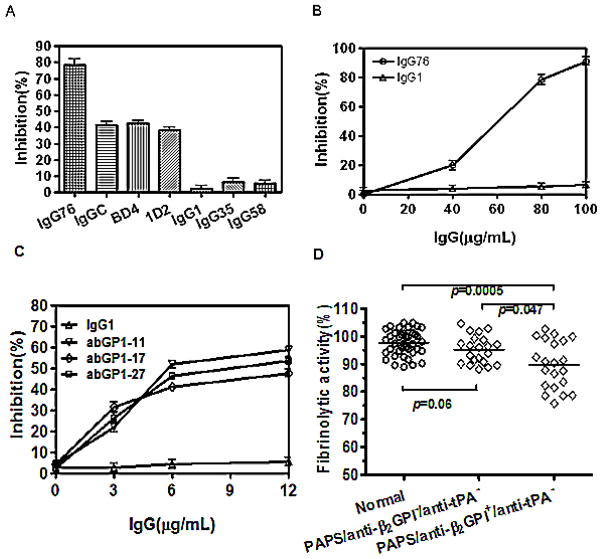

Anti-β2GPI antibodies inhibit the stimulatory effect of β2GPI on t-PA-dependent plasminogen activation

Two monoclonal anti-β2GPI antibodies (1D2 and BD4) inhibited t-PA-dependent plasminogen activation to a significantly greater extent than control murine IgG1 (P<0.0001, n=4) (Figure 6A). Purified IgG fractions from patients with APS also inhibited plasminogen activation in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 6A, B). To determine whether this effect was associated with anti-β2GPI antibodies or anti-t-PA antibodies (29), we used two approaches. First, we affinity-purified anti-β2GPI IgG from three patients, and tested the ability of the purified anti-β2GPI IgG to inhibit the ability of β2GPI to enhance t-PA-dependent plasminogen activation. As depicted in Figure 6C, the three affinity-purified anti-β2GPI antibody preparations inhibited plasminogen activation in a concentration-dependent manner, while a control human IgG preparation (IgG1) had not effect. We subsequently isolated whole IgG fractions from 22 patients with APS whose plasma contained IgG anti-β2GPI but not anti-t-PA antibodies (β2GPI+/t-PA−), and 21 patients whose plasma contained neither anti-β2GPI nor anti-t-PA antibodies (β2GPI−/t-PA−), and measured their ability to inhibit β2GPI-mediated stimulation of t-PA-dependent plasminogen activation. At a concentration of 80 μg/ml (533 nM), IgG fractions from β2GPI+/t-PA− patients caused significantly more inhibition of plasminogen activation than those from anti-β2GPI−/anti-t-PA− patients or normal controls (Figure 6D).

Figure 6. Anti-β2GPI antibodies inhibit β2GPI-mediated enhancement of plasminogen activation.

Plasminogen activation was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Percent inhibition by anti-β2GPI antibodies was calculated by comparing initial reaction rates in the absence or presence of antibodies. (A) IgG76, IgGC, IgG35 and IgG58 are anti-β2GPI antibody-containing IgG fractions from patients with APS, BD4 and ID2 are monoclonal anti-β2GPI antibodies, and IgG1 is normal human IgG. (B) Inhibition of t-PA-dependent plasminogen activation by increasing concentrations of anti-β2GPI IgG (IgG76), or control IgG (IgG1). (C) Anti-β2GPI antibodies were affinity purified from the plasma of 3 patients with APS and anti-β2GPI antibodies (abGPI-11, abGPI-17, abGPI-27), and their ability to inhibit β2GPI-dependent t-PA-mediated plasminogen activation determined. Each of the purified anti-β2GPI antibody preparations inhibited plasminogen activation in a concentration-dependent manner. (D) The effect of IgG fractions from 40 normal controls, 22 APS patients with anti-β2GPI, but not anti-t-PA antibodies (anti-β2GPI+/anti-tPA−), or 21 APS patients with neither anti-β2GPI nor anti-t-PA antibodies (anti-β2GPI−/anti-tPA−) on t-PA-dependent plasminogen activation in the presence of β2GPI. One outlying point in which an IgG fraction from a patient with anti-β2GPI caused marked inhibition of plasminogen activation (~60% activity) was removed for this analysis.

Discussion

Our studies demonstrate that β2GPI binds t-PA with high affinity and stimulates t-PA–dependent plasminogen activation. β2GPI enhanced the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) of t-PA-dependent plasminogen activation by approximately 20-fold, as a result of a decrease in the Km and an increase in Vmax (Table 1). The enhancement of plasmin generation and stimulation of fibrinolysis by β2GPI was also demonstrated in a fibrin gel (Figure 4). Moreover, the depletion of plasma β2GPI led to delayed clot lysis, which was restored upon repletion of purified β2GPI, suggesting that these findings are relevant in plasma.

The activity of full-length recombinant β2GPI expressed in 293T cells was similar to that of purified plasma β2GPI (Figure 1), suggesting that isolated plasma β2GPI was not denatured, and thus that the activity of β2GPI was not attributable to non-specific effects of denatured protein (30). The ability of recombinant β2GPI domain V to stimulate t-PA-dependent plasminogen activation was approximately 50% that of intact β2GPI, suggesting thatβ2GPI-V as well as other regions of β2GPI contribute to this activity. However, theβ2GPI Gly274-Cys288 peptide neither enhanced t-PA–dependent plasminogen activation nor significantly inhibited the binding of β2GPI to immobilized t-PA. Thus, if this region is involved in the interaction of β2GPI with t-PA, it likely requires conformational restraints imposed in the context of intact β2GPI. Additional studies employing site-directed mutagenesis and β2GPI mutants lacking specific β2GPI domains may be of value in further defining the role of this region, if any, in the interactions of β2GPI with t-PA.

Annexin A2 and the annexin A2-S100A10 heterotetramer are endothelial cell receptors for plasminogen and t-PA (16;31). Binding of t-PA and plasminogen to annexin A2 enhances plasmin generation by facilitating co-assembly of these reactants, and lowering the KM for their interaction (16;17). Cesarman-Maus et al. have described anti-annexin A2 antibodies in patients with APS that inhibit the fibrinolytic activity of this complex (32). While our laboratory has demonstrated a high-affinity interaction between β2GPI and annexin A2 (33), we have not yet directly assessed the effects of β2GPI on the ability of annexin A2 to enhance t-PA-mediated plasminogen activation either in isolation or on cell surfaces. However, Lopez-Lira et al reported an increase in plasmin generation on the surface of a human microvascular endothelial cell line (HMEC-1) following the addition of β2GPI (21), and we have observed that fluid-phase annexin A2 andβ2GPI stimulate t-PA-mediated plasminogen activation in an additive manner (not shown). Additional studies will clearly be required to better characterize the effects of β2GPI on cell surface plasminogen activator activity, and better define the roles of specific receptors in these effects. Such studies will require a full consideration of the complex nature of conformation-dependent interactions of β2GPI with phospholipids and proteins, such as apoER2 (34), factor XI (35), annexin A2 (33) and Lp(a) (36).

Lopez-Lira et al have reported thatβ2GPI binds glu-plasminogen and stimulates streptokinase-mediated plasminogen activation (21). Our preliminary studies also suggest low affinity binding (Kd > 1 μM) between glu-plasminogen and β2GPI, although the nature of the interactions between these two proteins requires further investigation. However, t-PA was not present in the system of Lopez-Lira, and thus our findings extend this work by demonstrating a direct interaction of β2GPI with t-PA. Taken together, however, these results suggest that in the presence of fibrin, β2GPI may potentially promote fibrinolysis through multiple pathways including 1) direct stimulation of t-PA amidolytic activity, 2) lowering of the KM for t-PA-mediated plasminogen activation, and 3) binding to fibrin and providing additional binding sites for plasminogen and t-PA at the fibrin surface (21).

Yasuda et al have reported that nicked β2GPI, which has been cleaved by plasmin between Lys317-Thr318 in domain 5, but not intact β2GPI, binds with low affinity to glu-plasminogen (Kd = 0.37 μM) (22). These investigators also observed that nicked β2GPI suppressed plasmin generation in the presence of t-PA, plasminogen and fibrin. Taken together with our findings, these results suggest that intact β2GPI may stimulate t-PA-mediated plasminogen activation and subsequently undergo cleavage by newly-formed plasmin. In turn, cleaved (“nicked”) β2GPI, if generated in sufficient concentrations in plasma, might limit additional plasmin generation (22).

The pathogenic effects of many “antiphospholipid” antibodies may be mediated through interactions with β2GPI. Indeed, Takeuchi et al observed diminished fibrinolysis in euglobulin fractions from APS patients, attributing this effect to impaired factor XII activation and activity (11).β2GPI has also been reported to protect t-PA from inhibition by plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1), an activity blocked by monoclonal antiphospholipid antibodies (12). In this report, we have demonstrated that monoclonal anti-β2GPI antibodies and affinity-purified anti-β2GPI antibodies from APS patients inhibit the ability of β2GPI to enhance t-PA-mediated plasminogen activation in a concentration-dependent manner. Morevoer, IgG fractions from APS patients containing anti-β2GPI antibodies caused significantly more inhibition of t-PA-mediated plasminogen activation than those from control patients or APS patients without anti-β2GPI antibodies. This activity was not due to anti-t-PA antibodies (29), and thus appears attributable to anti-β2GPI antibodies, suggesting another potential mechanism by which heterogeneous APL may contribute to the development of thromboembolic disease (7).

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants P50HL081011 and HL076810 to KRM, and grant 39970703 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China to GC.

References

- 1.Polz E, Kostner GM. The binding of β2-glycoprotein I to human serum lipoproteins. FEBS Lett. 1979;102:183–6. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(79)80955-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lozier J, Takahashi N, Putnam FW. Complete amino acid sequence of human plasma β2-glycoprotein I. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 1984;81:3640–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.12.3640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamboh MI, Mehdi H. Genetics of apolipoprotein H (beta 2-glycoprotein I) and anionic phospholipid binding. Lupus. 1998;7 (Suppl 2):S10–S13. doi: 10.1177/096120339800700203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohkura N, Hagihara Y, Yoshimura T, Goto Y, Kato H. Plasmin can reduce the function of human beta 2 glycoprotein I by cleaving domain V into a nicked form. Blood. 1998;91:4173–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galli M. Antiphospholipid syndrome: association between laboratory tests and clinical practice. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb. 2003;33(5–6):249–55. doi: 10.1159/000083810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lutters BC, De Groot PG, Derksen RH. beta 2 Glycoprotein I -- a key player in the antiphospholipid syndrome. Isr Med Assoc J. 2002;4:958–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyakis S, Giannakopoulos B, Krilis SA. Beta 2 glycoprotein I -- function in health and disease. Thromb Res. 2004;114:335–46. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nimpf J, Bevers EM, Bomans PHH, Till U, Wurm H, Kostner GM, et al. Prothrombinase activity of human platelets is inhibited by β2-glycoprotein I. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;884:142–9. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(86)90237-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ieko M, Ichikawa K, Triplett DA, Matsuura E, Atsumi T, Sawada K, et al. Beta 2 glycoprotein I is necessary to inhibit protein C activity by monoclonal anticardiolipin antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:167–74. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199901)42:1<167::AID-ANR20>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheng Y, Reddel SW, Herzog H, Wang YX, Brighton P, France MP, et al. Impaired thrombin generation in beta 2 glycoprotein I null mice. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13817–21. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010990200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takeuchi R, Atsumi T, Ieko M, Ichikawa K, Koike T. Suppressed intrinsic fibrinolytic activity by monoclonal anti beta 2 glycoprotein I autoantibodies: possible mechanism for thrombosis in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2002;119:781–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ieko M, Ichikawa K, Atsumi T, Takeuchi R, Sawada KI, Yasukouchi T, et al. Effects of beta 2 glycoprotein I and monoclonal anticardiolipin antibodies on extrinsic fibrinolysis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2000;26:85–90. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dobrovolsky AB, Titaeva EV. The fibrinolysis system: regulation of activity and physiologic functions of its main components. Biochemistry. 2002;67:99–108. doi: 10.1023/a:1013960416302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stack S, Cronow M, Pizzo SV. Regulartion of plasminogen activation by components of the extracellular matrix. Biochemistry. 1990;29:4966–70. doi: 10.1021/bi00472a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoylaerts M, Rijken DC, Lijnen HR, Collen D. Kinetics of the activation of plasminogen by human tissue plasminogen activator. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:2912–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hajjar K, Jacovina AT, Chacko J. An endothelial cell receptor for plasminogen/tissue plasminogen activator. I. Identity with annexin II. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21191–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cesarman GM, Guevara CA, Hajjar KA. An endothelial cell receptor for plasminogen/tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA). II. Annexin II-mediated enhancement of t-PA-dependent plasminogen activation. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21198–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kassam G, Choi KS, Ghuman J, Kang H-M, Fitzpatrick SL, Zackson T, et al. The role of annexin II tetramer in the activation of plasminogen. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4790–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roda O, Valero ML, Peiro S, Andreu D, Real FX, Nawroth P. New insights into the t-PA annexin A2 interaction. Is annexin A2 CYS8 the sole requirement for this association? J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5702–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207605200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cesarman MG, Hajjar KA. Molecular mechanisms of fibrinolysis. Br J Haematol. 2005;129:307–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lopez-Lira F, Rosales LL, Monroy MV, Ruiz OB. The role of beta 2 glycoprotein I (beta 2 GPI) in the activation of plasminogen. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1764:815–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yasuda S, Atsumi T, Ieko M, Matsuura E, Kobayashi K, Inagaki J, et al. Nicked beta 2 glycoprotein I: a marker of cerebral infarct and a novel role in the negative feedback pathway of extrinsic fibrinolysis. Blood. 2004;103:3766–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cai G, Guo Y, Shi J. Purification of apolipoprotein H by polyethylene glycol precipitation. Protein Expr Purif. 1996;8:341–6. doi: 10.1006/prep.1996.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kristensen T, Schousboe I, Boel E, Mulvihill EM, Hansen RR, M|ller KB, et al. Molecular cloning and mammalian expression of human β2-glycoprotein I cDNA. FEBS Lett. 1991;289:183–6. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81065-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goding J. Monoclonal antibodies: Principles and practice. 2. London: Academic Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagashima M, Yin ZF, Zhao L, White K, Zhu Y, Lasky N, et al. Thrombin activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI) deficiency is compatible with murine life. J Clin Invest. 2001;109:101–10. doi: 10.1172/JCI12119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classiciation criterial for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J, McCrae KR. Annexin II mediates endothelial cell activation by antiphospholipid/anti-β2 glycoprotein antibodies. Blood. 2005;105:1964–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cugno M, Cabbibe M, Galli M, Meroni PL, Caccia S, Russo R, et al. Antibodies to tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome: evidence of interaction between the antibodies and the catalytic domain of tPA in two patients. Blood. 2004;103:2121–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Machovich R, Owen WG. Denatured proteins as cofactors for plasminogen activation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;344:343–9. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacLeod TJ, Kwon M, Filipenko NR, Waisman DA. Phospholipid-associated annexin A2-S100A10 heterotetramer and its subunits. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25577–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301017200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cesarman-Maus G, Rìos-Luna N, Deora AB, Huang B, Villa R, del Carmen Cravioto M, et al. Autoantibodies against the fibrinolytic receptor, annexin 2, in antiphospholipid syndrome. Blood. 2006;107:4375–82. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma K, Simantov R, Zhang J-C, Silverstein R, Hajjar KA, McCrae KR. High affinity binding of β2-glycoprotein I to human endothelial cells is mediated by annexin II. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15541–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.20.15541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Lummel M, Pennings MT, Derksen RH, Urbanus RT, Lutters BC, Kaldenholven N, et al. The binding site in {beta} 2 glycoprotein I for ApoER2″ on platelets is located in domain V. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:36729–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504172200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi T, Iverson GM, Qi JC, et al. Beta 2- glycoprotein I binds factor XI and inhibits its activation by thrombin and factor XIIa: loss of inhibition by clipped beta 2 glycoprotein I. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 2004;101 (11):3939–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400281101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kochl S, Fresser F, Lobentanz E, Utermann G. Novel interaction of Apolipoprotein(a) with β2-glycoprotein I mediated by the kringle IV domain. Blood. 1997;90:1482–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cesarman GM, Guevara CA, Hajjar KA. An endothelial cell receptor for plasminogen/tissue plasminogen activator. II. Annexin II-mediated enhancement of t-PA-dependent plasminogen activation. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21195–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]