Abstract

External knee adduction moment can be reduced using footwear interventions, but the exact changes in in vivo medial joint loading remain unknown. An instrumented knee replacement was used to assess changes in in vivo medial joint loading in a single patient walking with a variable-stiffness intervention shoe. We hypothesized that during walking with a load modifying variable-stiffness shoe intervention: (1) the first peak knee adduction moment will be reduced compared to a subject's personal shoes; (2) the first peak in vivo medial contact force will be reduced compared to personal shoes; and (3) the reduction in knee adduction moment will be correlated with the reduction in medial contact force. The instrumentation included a motion capture system, force plate, and the instrumented knee prosthesis. The intervention shoe reduced the first peak knee adduction moment (13.3%, p=0.011) and medial compartment joint contact force (22%; p=0.008) compared to the personal shoe. The change in first peak knee adduction moment was significantly correlated with the change in first peak medial contact force (R2=0.67, p=0.007). Thus, for a single subject with a total knee prosthesis the variable-stiffness shoe reduces loading on the affected compartment of the joint. The reductions in the external knee adduction moment are indicative of reductions in in vivo medial compressive force with this intervention.

Keywords: knee osteoarthritis, biomechanics, load-altering intervention, variable-stiffness shoes, walking gait

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee afflicts more than 30% of the American population over the age of 651,2 with involvement of the medial compartment ten times more frequent than the lateral compartment.3,4 The increased incidence of medial knee OA is due in part to the high percentage of loading transmitted across the medial aspect of the knee during both static and dynamic loading, ∼60-80% of the total transmitted load.5-8

To reduce pain, improve function, and slow the rate of disease progression, surgical and mechanical interventions for OA often attempt to reduce medial compartment loading. Surgery such as high tibial osteotomy corrects malalignment of the knee and transfers loading from the affected medial compartment to the unaffected lateral compartment to relieve symptoms and slow the rate of cartilage breakdown.9,10 While direct force measurements in the medial compartment after surgery are impossible under normal circumstances, reductions in the adduction moment, a surrogate external measure for medial compartment loading, have been reported to range from ∼19%11 to 30%7 following high tibial osteotomy. Clinical studies reported that the adduction moment during walking is associated with the presence,12 severity,13.14 rate of progression,15 and treatment outcome7 of medial compartment OA. Therefore, the external adduction moment has been used to assess the outcomes of OA treatments.

Non-invasive load-altering interventions offer an attractive alternative to surgery to reduce knee joint loading. Such interventions include laterally-wedged inserts and specially-designed variable-stiffness shoes with a greater lateral sole stiffness compared to the medial sole. Both lateral wedging and variable-stiffness shoes reduce the external adduction moment in healthy individuals16-18 and OA subjects.19-23 However, inducing gait changes to reduce the adduction moment could produce other changes (e.g., adaptive muscle co-contraction) that may increase the medial compartment load. CChanges in in vivo loading remain unknown.

A recent study investigated changes in in vivo medial joint loading with two modified gait patterns, medial thrust gait and walking pole gait,24 and found the largest reductions in medial contact force during mid and late stance for both, with little reduction at the first peak during early stance. Changes in adduction moment were not investigated.24 In a previous study,25 adduction moment was related to the in vivo medial compartment joint force, but a correlation was not established between peak medial compartment contact force and peak adduction moment, often used to measure the effectiveness of interventions.

A recently developed instrumented total knee replacement with the ability to measure in vivo joint contact forces26 offers the opportunity to address the question of whether the variable-stiffness shoe that has been reported to reduce the adduction moment19,23 does in fact reduce the medial contact force of the knee. Our purpose was to examine whether inducing changes in adduction moment during walking with a variable-stiffness intervention shoe reduces medial compartment load. We hypothesized that during walking (1) the first peak external knee adduction moment will be reduced with the use of variable-stiffness intervention shoes compared to a subject's personal walking shoes, (2) the first peak in vivo medial compartment joint contact force will be reduced with the use of variable-stiffness intervention shoes compared to a subject's personal walking shoes, and (3) the reduction in knee adduction moment will be correlated with the reduction in medial compartment joint contact force.

Methods

A custom-designed instrumented knee prosthesis26 was implanted in the right knee of an 81-year-old male (170 cm, 64.5 kg) using a midvastus approach 1.5 years prior to testing, and the patient was well functioning at the time of testing. In vivo tibial forces were measured after informed consent was obtained. The femur was cut at 6° anatomic valgus and 3° external rotation with the posterior condyles as references using intramedullary alignment. A standard cruciate-retaining Sigma PFC femoral component (Depuy, Warsaw, IN) was cemented in place. The tibial cut was made at 0° anatomic valgus without any posterior slope using intramedullary alignment. The tibial canal was reamed using custom instrumentation developed for the stem and keel. The instrumented tibial prosthesis was cemented. A 10-mm polyethylene insert (Sigma PLI) was used. Postoperative deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis and rehabilitation were the same as for routine primary knee arthroplasty. Intraoperative passive flexion showed reasonable balance between the medial and lateral soft tissues, defined as <10% difference between the medial and lateral forces over the range of from 0 to 90° of flexion. On postoperative full-length standing AP radiographs, femoral component alignment was in 6° valgus to the anatomic femoral shaft axis, defined as a line joining the mid-point of two transverse lines at the upper and lower region of the middle third of the femur; tibial tray alignment was 90.1° relative to the anatomic tibial shaft, defined by a line drawn from the mid-point of the tibial plateau to the center of the talus.

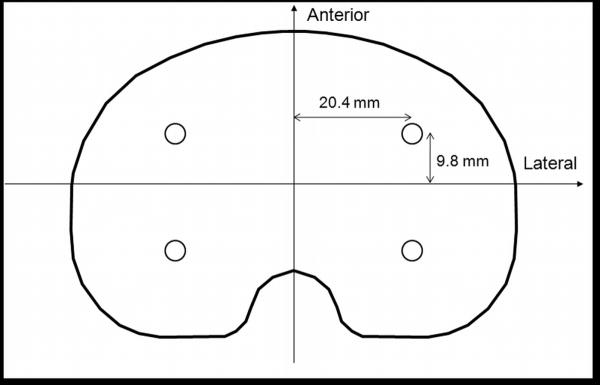

The instrumented prosthesis consisted of a titanium alloy tray instrumented with four uniaxial load cells, a microtransmitter, and an antenna.26 The uniaxial load cells were located 20.4 mm medial and lateral, and 9.8 mm anterior and posterior, of the center of the tibial tray, respectively (Fig. 1). The instrumented knee transmitted tibial force data from the four sensors at 70 Hz. Custom PC-based software was developed to read, display, and store data. Medial compartment contact loading was calculated as the sum of the medial anterior and medial posterior compressive loads.27 Similar calculations were performed for the lateral compartment. Total compressive contact force was calculated as the sum of the medial and lateral compressive loads (the sum of all four load cells). Loads were normalized to body weight (BW) for analyses.

Figure 1.

The four load cells were located 20.4 mm medial and lateral, and 9.8 mm anterior and posterior, of the center of the instrumented prosthesis, respectively.

Gait analysis was performed simultaneously with tibial force measurements. The subject performed 3 walking trials at each of 3 speeds in random order: self-selected slow (1.00 ± 0.07 m/s), normal (1.23 ± 0.08 m/s), and fast (1.38 ± 0.06 m/s), and in 2 shoe conditions, his own personal walking shoes and variable-stiffness intervention shoes. The variable-stiffness shoe was a normally-appearing athletic shoe (Fig. 2) with a sole made of compression molded ethylene vinyl acetate that has been custom-designed so that the lateral sole (Asker C durometer 55 ± 2) is 1.3-1.5 times stiffer than the medial sole (Asker C durometer 70-76 ± 2). The personal shoe had a sole of injection-molded EVA ethylene vinyl acetate (New Balance, Men's model 625).

Figure 2.

Variable-stiffness shoe with greater lateral sole stiffness (1.3-1.5×) versus medial sole stiffness.

Reflective markers were placed on the leg along the anterior superior iliac spine, greater trochanter, lateral tibial plateau, lateral malleolus, lateral aspect of the calcaneus, and lateral head of the fifth metatarsal. An 8-camera optoelectronic system for 3D motion analysis (Qualisys Medical AB; Gothenburg, Sweden) was used to collect marker data for 5 secs for each trial. Ground reaction force data were collected using a multi-component force plate placed in the center of the walkway (Bertec Corporation; Columbus, OH). Kinematic and force data were collected at a frequency of 120 Hz. The kinematic, ground reaction force, and tibial force data were resampled at a common frequency during postprocessing. To calculate external moments at each joint center, each limb segment (foot, shank, thigh) was idealized to be a rigid body. Inertial properties of the segments were taken from the literature.28 The positions of the joint centers at the hip, knee, and ankle were located relative to the positions of the skin markers at the greater trochanter, the lateral joint line of the knee, and the lateral malleolus, respectively. The flexion-extension axis was assumed to remain perpendicular to the plane of progression; the abduction-adduction and internal-external rotation axes of the hip, knee, and ankle moved with the thigh, shank, and foot segments, respectively.7 The external knee adduction moment for each trial was calculated from marker, force plate, and inertial segment data using an inverse dynamics approach,29 and normalized to bodyweight and height (Bw*Ht).

The 1st and 2nd peak external knee adduction moments, medial contact forces, and total contact forces were calculated as the maximum moments or forces during the 1st or 2nd half of stance phase, respectively. No clear peaks existed for lateral force data; therefore, average lateral contact force over the stance phase was investigated. Average medial and total contact forces over stance phase (i.e., the mean value from 0 to 100% stance phase) were also examined.

For hypotheses 1 and 2, to account for the source of variability of the speeds, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to compare the knee adduction moment and contact forces between shoe conditions, using walking speed as a covariate (α=0.05). Changes in stride length,7 toe-out,30 and average vertical ground reaction force were also analyzed using ANCOVA with speed as a covariate to investigate if changes in medial contact force between shoe conditions could be attributed to these sources. For hypothesis 3, linear regression analysis (α=0.05) was used to detect a relationship between change in first peak knee adduction moment and change in first peak medial contact force with the variable-stiffness intervention shoes versus the personal shoes. All statistical tests were performed in SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL).

Results

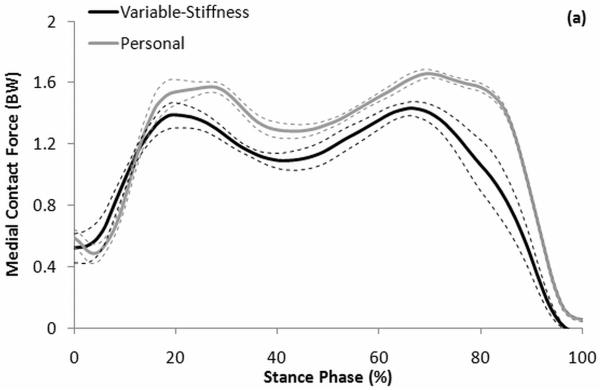

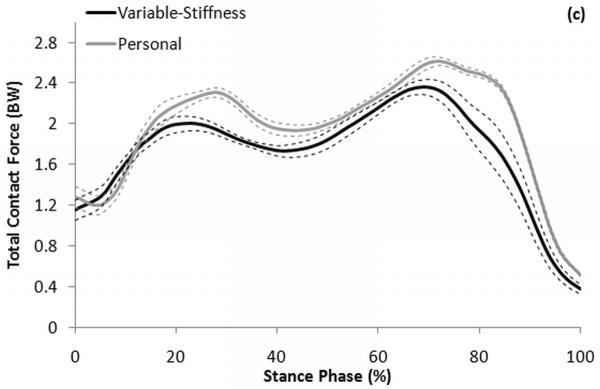

The variable-stiffness intervention shoes produced significant reductions in the knee adduction moment at the 1st peak compared to the personal shoes, with a reduction of 13.3% over all speeds (p=0.011; Table 1). A significant reduction was also found in the 2nd peak knee adduction moment with a reduction of 22% (p=0.032), and a significant mean reduction over all of stance phase of 22% (p=0.002; Table 1). Medial contact force was significantly reduced (Fig. 3a) with the intervention shoe by 12.3% (p=0.008) at the 1st peak, 10.9% (p=0.006) at the 2nd peak, and 18.9% over all of stance phase (p=0.001; Table 1). No differences were found in the mean lateral contact force over all of the stance phase when using the intervention shoe compared to the personal shoe (-3.5% reduction, p=0.318; Fig. 3b). Total joint contact force was significantly reduced (Fig. 3c) at the 1st peak (-10.7%, p=0.002), 2nd peak (-7.7%, p=0.033), and over all of the stance phase (-13.6%, p<0.001; Table 1). Stride length (p=0.949), toe-out (p=0.369), and average vertical ground reaction force (p=0.469; Table 2) were not significantly different between shoe conditions.

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviation of the 1st peak, 2nd peak, and average stance phase knee adduction moment, medial contact force, and total contact force from 9 trials of walking at 3 speeds (3 slow, 3 normal, 3 fast) with personal shoes and variable-stiffness intervention shoes.

| Personal Mean (SD) |

Variable-Stiffness Mean (SD) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Peak | |||

| Knee Adduction Moment (Bw*Ht) | 1.53 (0.13) | 1.32 (0.16) | 0.011 |

| Medial Contact Force (BW) | 1.69 (0.14) | 1.48 (0.18) | 0.008 |

| Total Contact Force (BW) | 2.39 (0.12) | 2.13 (0.18) | 0.002 |

| 2nd Peak | |||

| Knee Adduction Moment (Bw*Ht) | 1.14 (0.13) | 0.89 (0.32) | 0.032 |

| Medial Contact Force (BW) | 1.67 (0.08) | 1.49 (0.15) | 0.006 |

| Total Contact Force (BW) | 2.63 (0.14) | 2.43 (0.21) | 0.033 |

| Average | |||

| Knee Adduction Moment (Bw*Ht) | 0.66 (0.08) | 0.52 (0.14) | 0.002 |

| Medial Contact Force (BW) | 1.27 (0.16) | 1.03 (0.06) | 0.001 |

| Total Contact Force (BW) | 2.00 (0.15) | 1.73 (0.10) | <0.001 |

Figure 3.

Mean ± standard error curves (solid ± dashed lines) for (a) medial, (b) lateral, and (c) total knee contact force during stance phase from 9 trials of walking in personal shoes (grey) and variable-stiffness intervention shoes (black).

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviation of stride length, toe-out angle, and vertical ground reaction force from 9 trials of walking at 3 speeds (3 slow, 3 normal, 3 fast) with personal shoes and variable-stiffness intervention shoes.

| Personal Mean (SD) | Variable-Stiffness Mean (SD) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stride Length (m) | 1.47 (0.08) | 1.45 (0.12) | 0.949 |

| Toe Out (°) | 19.3 (2.0) | 20.0 (2.1) | 0.369 |

| Vertical Ground Reaction Force (N) | 536.2 (71.0) | 515.4 (5.7) | 0.369 |

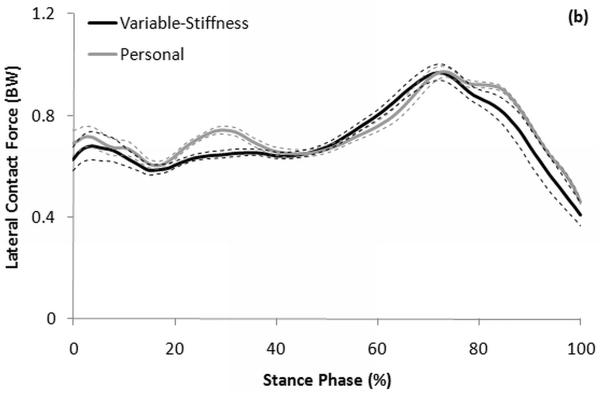

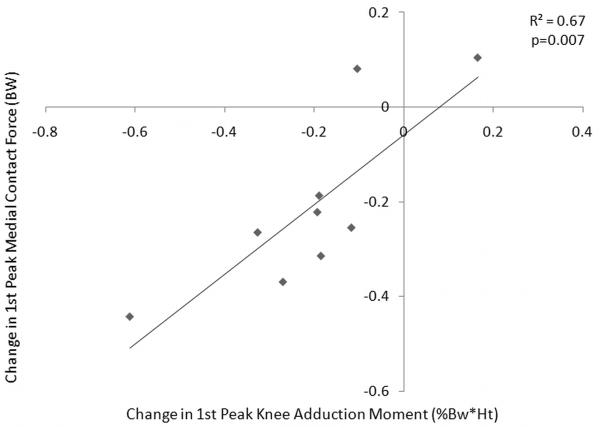

The change in 1st peak knee adduction moment with the variable-stiffness intervention shoe versus the personal shoe was significantly correlated with the change in 1st peak medial compartment contact force (R2=0.67, p=0.007). Increasing reduction in the knee adduction moment with the use of the variable-stiffness shoe was well-correlated with increasing reduction in the medial compartment contact force (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Correlation between change in 1st peak medial compartment contact force and change in 1st peak knee adduction moment with the variable-stiffness shoes versus the subject's personal shoes (R2=0.67, p=0.007).

Discussion

Previous research showed that load-modifying interventions such as variable-stiffness shoes can reduce the external knee adduction moment.17,19,23 However, in vivo changes in joint loading remained unknown. Thus, we examined whether variable-stiffness shoes reduced the adduction moment during walking, and if a decrease in adduction moment during walking induced a corresponding decrease in the medial compartment contact force. Our results demonstrated that for a single subject with a total knee prosthesis a variable-stiffness shoe reduces both the external knee adduction moment and the in vivo medial compartment joint contact force during level walking. The reductions in knee adduction moment (13% at the 1st peak to 22% at the 2nd peak and on average over all of the stance phase) are consistent with, or slightly higher than, those found in larger cohorts of healthy subjects16,17 and OA patients19-21 using lateral wedging and variable-stiffness shoes. The reductions seen in medial contact force, ranging from ∼12% at the 1st peak to 11% at the 2nd peak and nearly 19% over all of the stance phase, indicate that the reduction in the adduction moment with the variable-stiffness shoe does correspond to a reduction in medial contact force. The magnitude of the reductions in both adduction moment and medial contact force are consistent with levels that are reported to slow the rate of disease progression15 and may help to reduce symptoms in patients with medial compartment knee OA.

The reductions in medial contact force seen with the variable-stiffness shoe are on a similar order as the reductions seen using the same subject with two other gait modifications. Fregly et al.24 investigated reductions in medial contact force with two modified gait patterns, medial thrust gait and walking pole gait. The authors found reductions in medial contact force between 7% and 28% with medial thrust gait, and reductions throughout stance between 15% and 45% with walking pole gait. However, these reductions occurred mainly during mid and late stance, with little reduction in the 1st peak during early stance.24 We observed a significant force reduction during early stance, as well as throughout the entire stance phase.

The reduction in medial contact force with the variable-stiffness shoe in this patient was achieved without an increase in total joint contact force. Any attempt to induce changes in patterns of ambulation, such as with lateral wedging or gait modifications, could result in adaptive patterns of muscle co-contraction. Muscle co-contraction would increase the total force on the joint. Thus, the reduction in total joint contact force suggests the reduction in the adduction moment with the variable stiffness shoe was achieved without additional muscle co-contraction. In addition, the variable-stiffness shoe did not appear to shift loading from the medial to lateral compartment to achieve the reduction in medial joint loading. Rather, it may be that the spatial positioning of the leg is altered with the variable-stiffness shoe, that the acceleration of the upper body is changed resulting in a change in the moment arm of the ground reaction force vector, or that muscle co-contraction is reduced. The fact that the lateral compartment joint loading did not increase demonstrates that the shoe did not induce harmful loading that may be detrimental to the lateral compartment. This differs from the non-invasive gait modifications tested by Fregly et al.,24 for which increases in lateral joint loading were seen in the same patient tested in the present study. The changes that occur in medial, lateral, and total joint loading with laterally-wedged insoles remain unknown.

The reductions in medial contact force were also achieved without increases in toe-out angle, reductions in stride length, or reductions in ground reaction force. These results again suggest that for this subject the reduction in medial joint loading was due to the dynamic effect of the variable-stiffness sole shoe on changing the moment arm of the ground reaction force, as the knee adduction moment is generated by the combination of the ground reaction force passing medially to the center of the knee joint, and the perpendicular distance of this force from the joint center.29 Without a reduction in ground reaction force, the moment arm must be reduced.

Our results suggest that for this subject with an instrumented knee, changes in the 1st peak knee adduction moment are a good indication of changes in the peak medial contact force during walking with a variable-stiffness footwear intervention. A strong correlation existed between the change in 1st peak knee adduction moment with the variable-stiffness shoe and change in 1st peak medial compartment joint contact force, with nearly 70% of the change in medial contact force accounted for by the change in knee adduction moment. Due to the difficulty of invasive in vivo joint measurements, our study suggests that for this patient changes in knee adduction moment with a variable-stiffness footwear intervention provided a reliable measure of the change in medial joint force.

The primary limitation of this study is the use of a single subject with a total knee replacement, as the gait of a patient with an implanted knee may differ from that of a subject with a natural knee. However, the gait of the subject appeared normal, and the subject's walking speeds were within the range for normal subjects.31,32 The patterns of the ground reaction force and knee flexion/extension curves were also similar to those of normal subjects.32,33 Thus, it is unlikely that the gait pattern of this subject differs greatly from that of normal individuals. With only one subject, however, the applicability of our results to the general OA population is unknown, and the scope of inference can only be extended to this subject. Further investigation will be needed to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of this intervention in reducing the medial contact force in the general population.

In summary, we directly demonstrated that a variable-stiffness shoe with an increased lateral sole stiffness reduces the in vivo medial compartment contact force and the external knee adduction moment in a single subject with a force-sensing instrumented total knee prosthesis. Furthermore, the reduction in 1st peak knee adduction moment is indicative of the reduction in the medial compressive force with the intervention shoe. The variable-stiffness intervention shoe reduced loading on the affected compartment of the joint, and therefore might slow the rate of progression of cartilage breakdown and serve as a therapeutic intervention to delay the need for invasive surgery for medial compartment knee osteoarthritis.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided in part by NIH Grant #1R21EB4581 and OREF Grant #02-021. The authors thank Alexander Sox-Harris, PhD for his assistance with the statistical analyses.

References

- 1.Breedveld FC. Osteoarthritis – the impact of a serious disease. Rheumatology. 2004;43(suppl):i4–i8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felson DT, Naimark A, Anderson J, et al. The prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the elderly. The Framingham Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;308:914–918. doi: 10.1002/art.1780300811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahlback S. Osteoarthrosis of the knee. A radiographic investigation. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockholm) 1968;277(suppl):7–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas RH, Resnick D, Alazraki NP, et al. Compartmental evaluation of osteoarthritis of the knee: a comparative study of available diagnostic modalities. Radiology. 1975;116:585–594. doi: 10.1148/116.3.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andriacchi TP. Dynamics of knee malalignment. Orthop Clin North Am. 1994;25(3):395–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson F, Leitl S, Waugh W. The distribution of load across the knee: A comparison of static and dynamic measurements. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1980;62:346–349. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.62B3.7410467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prodromos CC, Andriacchi TP, Galante JO. A relationship between gait and clinical changes following high tibial osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:1188–1194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schipplein OD, Andriacchi TP. Interaction between active and passive knee stabilizers during level walking. J Orthop Res. 1991;9:113–119. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coventry MB. Upper tibial osteotomy. Clin Orthop. 1984;182:46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kettelkamp DB, Wenger DR, Chao EYS, Thompson C. Results of proximal tibial osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58:952–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wada M, Imura S, Nagatani K, et al. Relationship between gait and clinical results after high tibial osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;354:180–188. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199809000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baliunas AJ, Hurwitz DE, Ryals AB, et al. Increased knee joint loads during walking are present in subjects with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2002;10:573–579. doi: 10.1053/joca.2002.0797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mündermann A, Dyrby CO, Hurwitz DE, et al. Potential strategies to reduce medial compartment loading in patients with knee osteoarthritis of varying severity: Reduced walking speed. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1172–1178. doi: 10.1002/art.20132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma L, Hurwitz DE, Thonar EJ, et al. Knee adduction moment, serum hyaluronan levels, and disease severity in medial tibiofemoral osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1233–1240. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199807)41:7<1233::AID-ART14>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyazaki T, Wada M, Kawahara H, et al. Dynamic load at baseline can predict radiographic disease progression in medial compartment knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:617–622. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.7.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crenshaw SJ, Pollo FE, Calton EF. Effects of lateral-wedged insoles on kinetics at the knee. Clin Orthop. 2000;375:185–192. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200006000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher DS, Dyrby CO, Mündermann A, et al. In healthy subjects without knee osteoarthritis, the peak knee adduction moment influences the acute effect of shoe interventions designed to reduce medial compartment knee load. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:540–546. doi: 10.1002/jor.20157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmalz T, Blumentritt S, Drewitz H, Freslier M. The influence of sole wedges on frontal plane knee kinetics, in isolation and in combination with representative rigid and semi-rigid ankle-foot-orthoses. Clin Biomech. 2006;21:631–639. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erhart JC, Mündermann A, Elspas B, et al. A variable-stiffness shoe lowers the knee adduction moment in subjects with symptoms of medial compartment knee osteoarthritis. J Biomech. 2008;41:2720–2725. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butler RJ, Marchesi S, Royer T, Davis IS. The effect of a subject-specific amount of lateral wedge on knee mechanics in patients with medial knee osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:1121–1127. doi: 10.1002/jor.20423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerrigan DC, Lelas JL, Goggins J, et al. Effectiveness of a lateral-wedge insole on knee varus torque in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:889–893. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.33225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimada S, Kobayashi S, Wada M, et al. Effects of disease severity on response to lateral wedged shoe insole for medial compartment knee osteoarthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:1436–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erhart JC, Mündermann A, Elspas B, et al. Changes in knee adduction moment, pain, and functionality with a variable-stiffness walking shoe after 6 months. J Orthop Res. 2010 doi: 10.1002/jor.21077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fregly BJ, D'Lima DD, Colwell CW. Effective Gait Patterns for Offloading the Medial Compartment of the Knee. J Orthop Res. 2009;27:1016–1021. doi: 10.1002/jor.20843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao D, Banks SA, Mitchell KH, et al. Correlation between the knee adduction moment torque and medial contact force for a variety of gait patterns. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:789–797. doi: 10.1002/jor.20379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D'Lima DD, Townsend CP, Arms SW, et al. An implantable telemetry device to measure intra-articular tibial forces. J Biomech. 2005;38:299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao D, Banks SA, D'Lima DD, et al. In vivo medial and lateral tibial loads during dynamic and high flexion activities. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:593–602. doi: 10.1002/jor.20362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dempster WT, Gaughran GRL. Properties of body segments based on size and weight. Am J Anat. 1967;120:33–54. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andriacchi TP, Natarajan RN, Hurwitz DE. Musculoskeletal dynamics, locomotion, and clinical applications. In: Mow VC, Hayes WC, editors. Basic Orthopaedic Biomechanics. Second. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. pp. 37–67. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang JW, Kuo KN, Andriacchi TP, Galante JO. The influence of walking mechanics and time on the results of proximal tibial osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:905–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andriacchi TP, Galante JO, Fermier RW. The influence of total knee-replacement design on walking and stair-climbing. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64:1328–1335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chao EY, Laughman RK, Schneider E, Stauffer RN. Normative data of knee joint motion and ground reaction forces in adult level walking. J Biomech. 1983;16:219–233. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(83)90129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Besier TF, Sturnieks DL, Alderson JA, Lloyd DG. Repeatability of gait data using a functional hip joint centre and a mean helical knee axis. J Biomech. 2003;36:1159–1168. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]