Abstract

Purpose

To apply a diathesis × stress model to testing the association between peer victimization and depression in a sample of preadolescent girls.

Methods

DSM-IV symptoms of depression symptoms were measured at ages 9 and 11, assertiveness and peer victimization were assessed by youth report at age 9.

Results

The interaction of low levels of assertiveness and high peer victimization at age 9 was predictive of depression symptoms at age 11, controlling for earlier depression symptoms.

Conclusions

The results extend the literature on peer relations and depression by identifying a group of girls who may be particularly vulnerable to the stress of negative peer interactions.

Keywords: girls, depression, peer victimization, assertiveness

Being a victim of negative peer experiences is significantly associated with depression,1 especially for girls.2 The rate of negative peer experiences, however, is much higher than the rate of depression.3 Thus, the majority of girls who are victimized do not develop depression. Using a diathesis × stress model of depression, we propose that lack of assertiveness serves as an individual risk factor and that that peer victimization is a stressor that moderates the association between lack of assertiveness and depression. There is theoretical4 and empirical5 support for proposing lack of assertiveness as a diathesis for depression in girls. Lack of assertiveness would be most likely to confer risk for depression when a child encounters a context in which assertiveness would be adaptive. Peer victimization is one such context.6 The fact that girls are encouraged by socializing agents to be rule abiding and empathic may work against the increasing demands for autonomy and assertiveness during adolescence.7

In the present study, we test the hypothesis that peer victimization moderates the association between assertiveness and depression symptoms in girls measured at ages 9 and 11 years.

Methods

Sample

Girls were recruited from a larger community-based study. The sample was enriched for risk for depression by oversampling girls with scores at or above the 75th percentile by self- and/or maternal-report (n = 135) at the most recently completed assessment for the community-based study (age 8); an equal number of girls from the remainder were randomly selected for inclusion (n= 136). Of the 263 families eligible to participate in the depression sub-study, 232 (88.2%) agreed to participate and completed the first assessment at age 9 years. Retention at age 11 was 97.0%.

Measures

Depression symptoms were measured at ages 9 and 11 using the Schedule for Affective Disorders for School-Age Children,8 which was administered to the child. Reliability for total number of symptoms was high (ICC = .92 and .97 at ages 9 and 11, respectively). A square root transformation yielded an approximate normal distribution.

Girls’ reports of victimization by peers at age 9 was measured using the Peer Experience Questionnaire.9 This nine-item scale includes victimization by physical aggression and exclusion rated on a scale ranging from never to a few times per week. The alpha in the present study was .82. The distribution of the scores was skewed and transformation of the scale did little to normalize the distribution. Thus, the scores were dichotomized at the upper quartile.

Assertiveness at age 9 was measured by child report on the assertion subscale of the Social Skills Rating System.10 The subscale consists of 10 items on initiation of social interactions (e.g., asks classmates to join activity), responding to peer pressure and insults (ignores teasing by peers, which is reverse coded) each rated on a 3-point scale and summed. In the present sample the alpha for this scale was .64. The distribution of the scores was normal.

Most girls (69.8%) were African American or African American and other racial backgrounds (e.g., European American). Poverty was defined as receipt of public assistance (e.g., food stamps, Medicaid insurance).

Results

Lack of assertion was correlated with peer victimization at age 9 (Spearman’s rho = .18, p < .01). Depression symptoms at ages 9 and 11 were moderately correlated (Spearman’s rho = .40, p < .01). Depression symptoms at ages 9 and 11 were associated with lack of assertion (Spearman’s rho = .29 and .20, p < .01, respectively) and peer victimization (Spearman’s rho = .30 and .33, p < .01, respectively).

Regression analysis was used to test the association between lack of assertion and peer victimization at age 9 and depression symptoms at age 11, controlling for depression at age 9 (Table 1). Lack of assertion was centered Depression symptoms, race, and poverty assessed at age 9 were entered first and accounted for a substantial amount of the variance in depression symptoms at age 11 (ΔR2= .23, p < .001). Lack of assertion and peer victimization were entered on step 2 (ΔR2 = .04, p < .01); victimization, but not lack of assertion, was positively associated with future depression. Step 3 revealed a significant interaction between lack of assertion and peer victimization in predicting age 11 depression (ΔR2 = .03, p < .01).

Table 1.

Hierarchical regression testing main and interactive effects of lack of assertion and peer victimization at age 9 on DSM-IV symptoms of depression at age 11.

| B | SE B | β | t | ΔR2 | ΔF (df) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | .23 | 21.57*** (3, 217) | ||||

| Depression symptoms (age 9) | .34 | .06 | .35 | 5.77*** | ||

| Receipt of public assistance versus none | .17 | .10 | .10 | 1.66 | ||

| African American versus European American Race | .41 | .11 | .23 | 3.73*** | ||

| Step 2 | .04 | 5.65** (2, 215) | ||||

| Depression symptoms (age 9) | .29 | .06 | .30 | 4.83*** | ||

| Receipt of public assistance versus none | .12 | .10 | .07 | 1.18 | ||

| African American versus European American Race | .38 | .11 | .22 | 3.53*** | ||

| Lack of assertion | .01 | .02 | .04 | 0.68 | ||

| High versus Low/Average Peer Victimization | .36 | .11 | .19 | 3.17** | ||

| Step 3 | .03 | 8.09** (1, 214) | ||||

| Depression symptoms (age 9) | .28 | .06 | .29 | 4.73*** | ||

| Receipt of public assistance versus none | .13 | .10 | .08 | 1.34 | ||

| African American versus European American Race | .44 | .11 | .25 | 4.07*** | ||

| Lack of assertion | −.20 | .02 | −.08 | −1.07 | ||

| High versus Low/Average Peer Victimization | .29 | .11 | .16 | 2.61** | ||

| Lack of assertion × High versus Low/Average Peer Victimization | .09 | .03 | .21 | 2.84** |

p < .01.

p < .001.

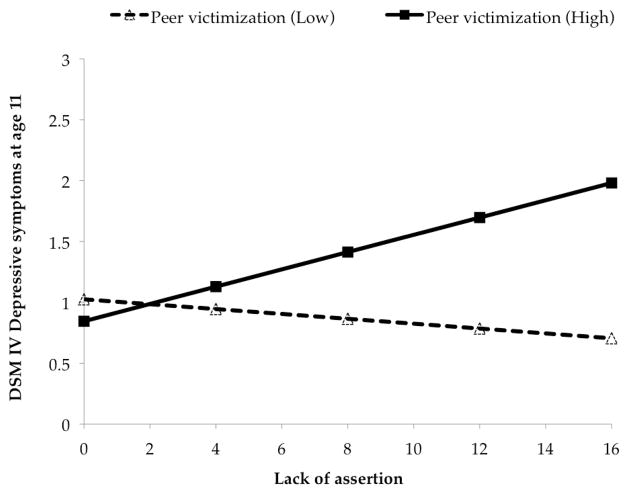

To probe the interaction effect, the association between depression symptoms (at age 11) and the lack of assertion was plotted at high and low levels of peer victimization with all the covariates in the final regression controlled and using transformed depression symptoms (Figure 1). When peer victimization was high (top quartile) there was a significant prospective association between lack of assertion and depression (β = .28, p < .01), such that girls low in assertiveness reported more depressive symptoms two years later. In the context of low or average levels of peer victimization, lack of assertion was not predictive of future depression.

Figure 1.

Interaction between lack of assertion and peer victimization at age 9 on depression symptoms at age 11

Although assertiveness and peer victimization were assessed concurrently, we cautiously explored whether peer victimization mediated the association between lack of assertiveness and depression symptoms. The total indirect relation between lack of assertion at age 9 and depressive symptoms at age 11, mediated through peer victimization (controlling for depression symptoms at age 9), was not significant, B = −13.57, SE = 12.65, p > .10.

Discussion

These results extend the literature on peer relations and depression by identifying a group of girls who may be particularly vulnerable to the stress of negative peer interactions. Girls who described themselves as unassertive and who reported a high level of peer victimization had twice as many symptoms of depression two years later as girls who reported peer victimization only or lack of assertion only.

An alternative to the moderation model that we have tested is a meditational model. Lack of assertiveness may lead girls to be targets of peers who victimize others. Unassertive girls may also be more likely to experience chronic and persistent victimization by peers. Our concurrent assessment of assertiveness and peer victimization made testing a meditational model difficult. Preliminary exploration of this effect, however, yielded no support for a meditational model.

A limitation of the present study is the reliance on self-report for all the measures, which raises the concern of inflated levels of associations. In addition, the use of an enriched sample for risk for depression, while increasing the power to detect significant effects, may have decreased generalizability of the findings to other populations.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grant R01 MH66167 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Dr Keenan. The authors thank the families participating in the Learning About Girls’ Emotions Study.

Contributor Information

Kate Keenan, University of Chicago

Alison Hipwell, University of Pittsburgh

Xin Feng, University of Pittsburgh

Michal Rischall, University of Pittsburgh

Angela Henneberger, University of Pittsburgh

Susan Klosterman, University of Pittsburgh

References

- 1.Panak WF, Garber J. Role of aggression, rejection, and attributions in the prediction of depression in children. Dev Psychopathol. 1992;4:145–165. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klomek AB, Marrocco F, Kleinman M, Schonfeld IS. Gould MS Bullying, depression, and suicidality in adolescents. J Amer Acad of Child Adolesc Psychiat. 2007;46:40–49. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000242237.84925.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borg MG. The extent and nature of bullying among primary and secondary school children. Educatio Res. 1999;41:137–153. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abramson LY, Seligman MEP, Teasdale JD. Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. J Abnorm Psychol. 1978;87:49–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartlage S, Arduino K, Alloy LB. Depressive personality characteristics: State dependent concomitants of depressive disorder and traits independent of current depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107:349–354. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharp S. Self-esteem, response style and victimization: Possible ways of preventing victimization through parenting and school based training programmes. School Psychol Inter. 1996;17:347–357. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keenan K, Hipwell AE. Preadolescent clues to understanding depression in girls. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2005;8:89–105. doi: 10.1007/s10567-005-4750-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent DA, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): Initial Reliability and Validity Data. J Amer Acad of Child Adolesc Psychiat. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vernberg E, Jacobs A, Hershberger S. Peer victimization and attitudes about violence during early adolescence. J Clin Child Psychol. 1999;28:386–395. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gresham F, Elliot S. The Social Skills Rating Systems. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1990. [Google Scholar]