Abstract

Palmyrolide A (1) is a new neuroactive macrolide isolated from a marine cyanobacterial assemblage composed of Leptolyngbya cf. and Oscillatoria spp. collected from Palmyra Atoll. It features a rare N-methyl enamide and an intriguing t-butyl branch; the latter renders the adjacent lactone ester bond resistant to hydrolysis. Consistent with its significant suppression of calcium influx in cerebrocortical neurons (IC50=3.70 µM), palmyrolide A (1) showed relatively potent sodium channel blocking activity in neuro-2a cells (IC50=5.2 µM), without appreciable cytotoxicity.

Suppression and/or activation of spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations of murine cerebrocortical neurons1 has proven to be an extremely sensitive screening method for the discovery of new neurotoxins, including the recently reported cyanobacterial metabolites hoiamide A,2a alotamide A,2b and palmyramide A.2c In the case of hoiamide A, further pharmacological characterization found it to be a partial agonist at neurotoxin site 2 of voltage-gated sodium channels (VGSCs).2a

Primary cultures of cerebrocortical neurons allow the detection of two distinct actions when cells are loaded with the Ca2+ sensitive fluorescent dye, fluo-3.1 First, those metabolites that trigger Ca2+ influx can be easily revealed by monitoring for this ion using a Fluorometric Imaging Plate Reader (FLIPR). Secondly, because these cultures display spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations, they provide a robust screening system for the discovery of small molecule ion channel modulators. Synchronized Ca2+ oscillations in cultured neurons are considered to be a neuronal network phenomenon dependent on VGSC-mediated action potentials.1,3 Thus, the latter measurement allows detection of VGSC antagonists (as opposed to activators), glutamate (AMPA and mGluR) receptor antagonists, adenosine A1 receptor agonists, and other compounds that disrupt neuronal action potentials or glutamate neurotransmission.1,3 Glutamate-mediated intracellular Ca2+ overload is known to contribute to neuronal death in several human pathological conditions (hypoxia-ischemia, hypoglycemia trauma, epilepsy)4,5 and possibly neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s, and motor neuron disease.6,7

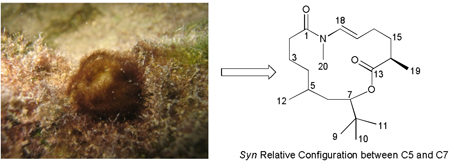

As part of our drug discovery screening efforts, we determined that the extract of a cyanobacterial assemblage, collected from Palmyra Atoll in the Northern Pacific Ocean, exhibited significant suppression of Ca2+ oscillations in cultured mouse cerebrocortical neurons. A two-pronged taxonomic approach, consisting of both detailed morphological characterization and phylogenetic analysis based on the SSU (16S) rRNA genes (see SI), revealed two genera of filamentous cyanoabcteria, Leptolyngbya cf. sp. and Oscillatoria sp. A portion of the cyanobacterial extract (0.2768 g) was subjected to bioassay and 1H NMR-guided fractionation to yield 10.2 mg (3.7%) of pure palmyrolide A (1) {[α]23D −29 (c 0.9, CHCl3)}, as the only neuroactive component. Unfortunately, efforts directed to identify the actual producer of 1 in the assemblage via MALDI imaging techniques2c were not successful, due in part to the lack of live cultures of these organisms.

HRESIMS of 1 yielded an [M+H]+ peak at m/z 338.2687 (calcd for C20H36O3N, 338.2690), consistent with the molecular formula C20H35O3N and four degrees of unsaturation. The most intriguing resonance in its 1H NMR spectrum (Table 1 and SI) was an intense singlet at δ0.86 (nine protons), which could be attributed to three isochronous methyl groups comprising a t-butyl moiety.8 Also present were the methyl doublets at δ0.90 and δ1.21, as well as the N-methyl singlet at δ3.04. The 1H NMR of 1 was completed by a deshielded methine proton at δ4.88 and a terminal 1,2-disubstituted vinylic system represented by protons at δ5.27 (dt) and δ6.47 (d). The presence of a t-butyl moiety was supported in the 13C NMR spectrum of 1 by a very intense resonance at δ26.1, as well as a quaternary carbon at δ35.2. Additionally, the deshielded carbons at δ117.3 and δ130.6 were in agreement with a 1,2-disubstituted double bond, whereas the carbonyls at δ172.9 and δ175.3 indicated a total of two ester or/and amide functionalities. As detailed below, extensive analysis of these 1H and 13C NMR resonances using HSQC, HMBC, COSY and NOESY led us to deduce the planar structure of 1.

Table 1.

NMR spectroscopic data (600 MHz, CDCl3) of palmyrolide A (1).

| carbon | δCa | type | δH, multiplicity (J in Hz)b | HMBCc | COSY | NOESY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 172.9 | |||||

| 2 | 34.4 | CH2 | 2.38 m | 1, 3, 4 | 3a, 3b | 4a, 4b, 18 |

| 3a | 24.3 | CH2 | 1.57 m | 1, 2, 4, 5 | 2, 3b, 4a, 4b | 18 |

| 3b | 1.78 m | 1, 2, 4, 5 | 2, 3a, 4a, 4b | 7, 18, 19 | ||

| 4a | 34.6 | CH2 | 1.06 m | 2, 3, 5, 6, 12 | 3a, 3b, 4b, 5 | 2, 6a, 7 |

| 4b | 1.33 m | 2, 3, 5, 12 | 3a, 3b, 4a | 2, 6b, 7, 18, 19 | ||

| 5 | 29.3 | CH | 1.48 m | 6, 7 | 4a, 6a, 12 | 7, 18, 19 |

| 6a | 35.6 | CH2 | 1.38 ddd (1.5, 8.5, 14.5) | 4, 5, 12 | 5, 6b, 7 | 4a, 9/10/11, 12 |

| 6b | 1.66 ddd (3.0, 11.0, 14.5) | 4, 5, 7, 12 | 6a, 7 | 4b, 9/10/11, 12 | ||

| 7 | 76.9 | CH | 4.88 dd (1.5, 11.0) | 5, 8, 9/10/11, 13 | 6a, 6b | 3b, 4a, 4b, 5, 9/10/11, 12 |

| 8 | 35.2 | |||||

| 9/10/11 | 26.1 | 3xCH3 | 0.86 s | 6, 7, 8 | 6a, 6b, 7, 19 | |

| 12 | 20.6 | CH3 | 0.90 d (6.5) | 4, 5, 6 | 5 | 6a, 6b, 7 |

| 13 | 175.3 | |||||

| 14 | 38.8 | CH | 2.47 m | 13, 15, 16, 19 | 15, 19 | |

| 15 | 32.8 | CH2 | 1.78 m | 13, 14, 16, 17, 19 | 14, 16 | 17 |

| 16 | 27.0 | CH2 | 2.29 m | 14, 15, 17, 18 | 15, 17, 18 | 19 |

| 17 | 117.3 | CH | 5.27 dt (7.5, 14.0) | 15, 16, 18 | 16, 18 | 15, 20 |

| 18 | 130.6 | CH | 6.47 d (14.0) | 1, 16, 17, 20 | 16, 17 | 2, 3a, 3b, 4b, 5 |

| 19 | 16.8 | CH3 | 1.21 d (7.0) | 13, 14, 15 | 14 | 3b, 4b, 5, 9/10/11, 16 |

| 20 | 31.7 | NCH3 | 3.04 s | 1, 17, 18 | 17 |

Recorded at 150 MHz.

Recorded at 600 MHz.

From proton to the indicated carbon.

The intense singlet at δ0.86 (H9, H10, H11) showed HMBC correlations with the quaternary carbon C8 (δ35.2), oxymethine C7 (δ76.9), and methylene carbon C6 (δ35.6) (Figure 1A). This last carbon was found by HSQC to bear the diastereotopic proton resonances H6a (δ1.38) and H6b (δ1.66), which according to the COSY spectrum, participated in a spin system (I in Figure 1) that included the flanking methines H7 (δ4.88) and H5 (δ1.48), both diastereotopic methylene pairs H4a (δ1.06)/H4b (δ1.33) and H3a (δ1.57)/H3b (δ1.78), and a final third methylene H22 (δ2.38). The HMBC data obtained for all of these protons correlated with the COSY-derived sequence above, and enabled us to position both the carbonyl C1 (δ172.9) as the terminating element of the carbon chain (via correlations from H3a, H3b and H2), and the methyl branch H12 (δ0.90, d, J = 6.5 Hz) at C5 [correlations from H12 to δ34.6 (C4), δ29.3 (C5), and δ35.6 (C6)]. Finally, the oxymethine proton H7 (δ4.88) displayed, among others, a strong HMBC correlation with carbonyl C13 (δ175.3), confirming the presence of an ester linkage as suggested by its deshielded 1H NMR chemical shift value.

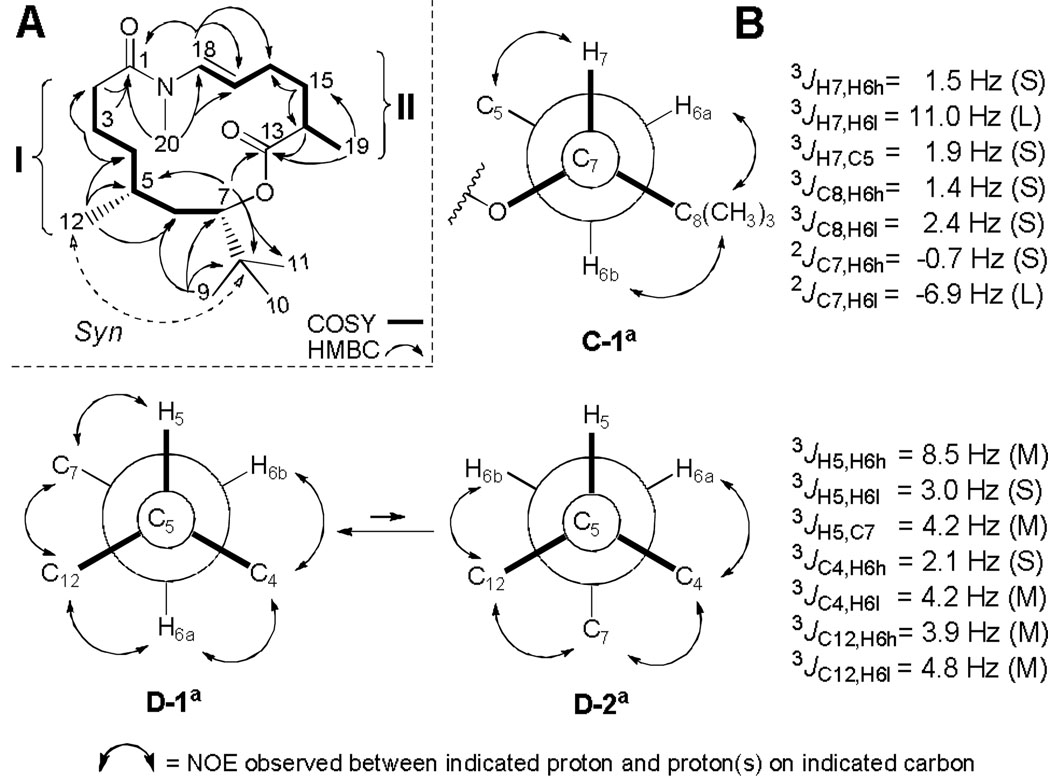

Figure 1.

(A) Representative 2D NMR correlations and (B) J-based configuration analysis for palmyrolide A (1) (S, small; M, medium; L, large; H6a, proton at high field; H6b, proton at low field). aRotamer designation according to Murata.9

This ester functionality accounted for the second of four unsaturations present in metabolite 1, and comprised the start of a second carbon chain further elongated by the methyl-substituted methine H14 (δ2.47), according to HMBC correlations from methyl H19 (δ1.21) and H14 itself to C13. COSY data indicated that both of these proton resonances belonged to a second spin system (II) that sequentially included the two methylene pairs H15 (δ1.78) and H16 (δ2.29), as well as vinylic protons H17 (δ5.27, dt, J = 7.5, 14.0 Hz) and H18 (δ6.47, d, J = 14.0 Hz). A vicinal 3JH17,H18 of 14.0 Hz and the doublet multiplicity displayed by H18 confirmed this as a terminal (E)-1,2-disubstituted double bond. Furthermore, both 1H (δ6.47) and 13C (δ130.6) chemical shifts at C18 were consistent with the presence of an attached nitrogen atom. Conclusive proof of an N-methyl amide functionality at this position was provided by HMBC correlations from the methyl singlet H20 (δ3.04) to carbon resonances C17 (δ117.3), C18 (δ130.6), and C1 (δ172.9). The latter key HMBC correlation, along with H18 to C1, assembled a fifteen-membered macrocyclic ring structure for palmyrolide A (1) which satisfied all of the required degrees of unsaturation and possessed a molecular formula consistent with the HRESIMS data.

The relative configuration for the 1,3-methine system C5–C7 was determined via J-based configuration analysis.9 First, the diastereotopic methylene protons H26 (δa1.38, δb1.66) were stereospecifically assigned with respect to H7 (δ4.88), according to the magnitude of the coupling constants provided by the 1H NMR, HETLOC10 and HSQMBC11 spectra (Figure 1B). Thus, H7 was found to be gauche to H6a (δ1.38) and anti to H6b (δ1.66), and the rotamer was assigned as C-1 (S, L, S, S, S, S, L). In a second step, we evaluated the relationship between methine H5 (δ1.48) and these stereospecifically defined H6-methylene protons. In this case, intermediate values for the homonuclear 3JH5,H6a (8.5 Hz) and four out of the five heteronuclear coupling constants led us to consider two major rotamers around the C5–C6 carbon bond, with H5/H6a exhibiting both anti and gauche orientations. Fortunately, all six of the possible rotamer pairs with the different prochiral assignments for methylene protons can be unequivocally distinguished using their full arrangement of J values.9 The only combination in agreement with our data corresponded to the rotamer pair D-1/D-2 (M, S, M, S, M, M, M). Finally, the proposed syn configuration between H5-H26-H7 (Figure 1A) was in agreement with the NOE interactions observed among these protons.

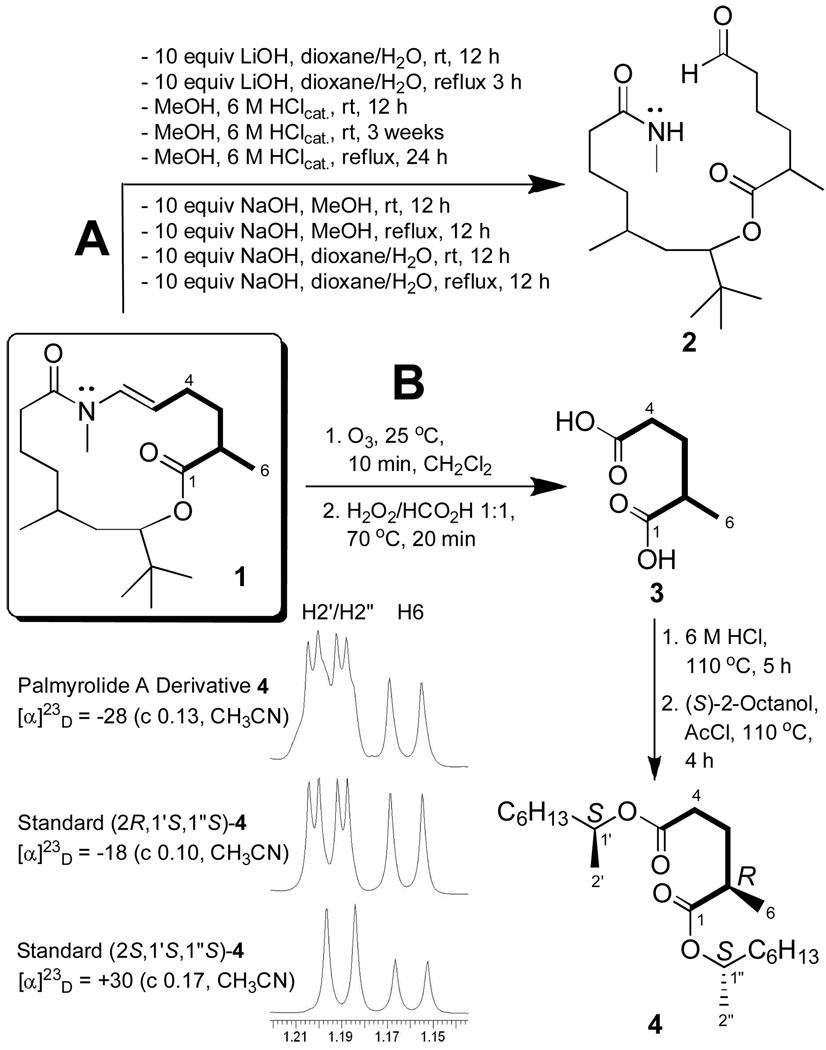

Determination of the absolute configuration of 1 was challenging due to a remarkable resistance of the ester group at C13 to hydrolysis (Figure 2, route A). Our initial strategy involved selective hydrolysis of this moiety, followed by sequential derivatization of the resulting C7-secondary hydroxyl and the C13-carboxyl group with Mosher’s acid chloride and PGME, respectively.12,13 However, both acid and basic hydrolysis conditions afforded compound 2, which undergoes further addition reactions to the aldehyde functionality, as indicated by the presence of several minor analogues in the crude reaction products (see SI for a mechanistic proposal on the formation of 2). Furthermore, the expected C1–C12 t-butyl hydroxyacid derived from 1 was not isolated even under more strenuous reaction conditions, suggesting the possibility of dehydration at C7 (the δ4.88 oxymethine disappears in the 1H NMR spectra of reaction crudes).

Figure 2.

Derivatization of palmyrolide A (1). (A): all reactions approx. 7 mM of 1 (2 mL). (B): representative section of the 1H NMR spectrum (500 MHz, CDCl3, see SI).

The unexpected stability of this ester, clearly due to a combination of steric and electronic effects provided by the contiguous t-butyl substituent at C7, and perhaps assisted by the C6 methyl group, leads us to speculate that cyanobacteria might produce secondary metabolites exhibiting this architecture so as to prevent cleavage of the lactone ester bond and preserve the bioactive macrocycle under a wide variety of conceivable environmental conditions. Our speculation that the t-butyl group in palmyrolide A protects against lactone hydrolysis is consistent with known principles in medicinal chemistry (e.g. pivalic acid esters) and represents an interesting chemical biology concept that warrants further exploration.

The configuration of the stereocenter at C14 was determined by ozonolysis and oxidative workup of palmyrolide A (1), followed by acid hydrolysis of the resulting crude reaction product to afford 2-methylglutaric acid (3), which is commercially available as its pure (R)-(−)- and (S)-(+)-enantiomers (route B). Further derivatization with (S)-(+)-2-octanol and acetyl chloride afforded the amiable diester 4 which was more easily detected and purified than its diacid precursor. Comparison of NMR data and specific rotation values measured for 4 and the similarly derivatized standards (see SI), led to assignment of the C14 chiral center as R. Unfortunately, this procedure failed to produce a suitable C1–C12 derivative, hindering our efforts to assign the absolute configuration at C5 and C7 (relative configuration shown in Figure 1A).

Palmyrolide A (1) is structurally related to the laingolides, initially reported from Papua New Guinea specimens of Lyngbya bouillonii.14 However, given the morphological similarities between Lyngbya and Oscillatoria cyanobacteria, and the fact that the laingolides producer was described solely from morphological characters rather than with the inclusion of phylogenetic analysis, we speculate that the laingolides may have been actually isolated from an Oscillatoria sp. Biogenetically,15 1 appears to derive from a combination of PKS and NRPS pathways, with its t-butyl appendage likely assembled from malonyl-CoA and three methyl groups donated from S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM).16 Both the C19 and C20 methyl groups likely also come from SAM, whereas the C12 methyl resides at a predicted carbonyl site in the nascent polyketide, and thus, should be produced by a β-branch mechanism involving an HMGCoA synthase cassette.17 A predicted NRPS module next adds glycine that is ketide extended, reduced at the β-carbonyl, dehydrated, and double bond isomerized from C16–C17 to form the C17–C18 enamide. Cyclization to 1 likely occurs coincident with offloading from this final NRPS module, but must overcome the extreme steric congestion that is present about this ester functionality.18

Pure palmyrolide A (1) showed significant inhibition of Ca2+ oscillations in murine cerebrocortical neurons, with an IC50 value of 3.70 µM (2.29–5.98 µM, 95% CI) (see SI). Additionally, in an assay designed to detect sodium channel blocking activity using mouse neuroblastoma (neuro2a) cells, compound 1 suppressed the veratridine- and ouabain-induced sodium overload that leads to cytotoxicity, with an IC50 of 5.2 µM. Finally, palmyrolide A was not cytotoxic when tested against H-460 human lung adenocarcinoma cells up to 20 µM. These results suggest that palmyrolide A (1) may function as a VGSC antagonist to suppress spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations and to protect against veratridine-induced sodium influx, making it an intriguing candidate for further pharmacological exploration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank A. Jansma (UCSD) and Y. Su (UCSD) for assistance with NMR and HRMS data acquisition, respectively. Support was provided by NIH NS053398 (W.H.G and T.F.M), NSF CHE-0741968 (NMR, UCSD) and Consejo de Ciencia y Tecnologia of Mexico (I.S.M).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental, full NMR data of 1, 2 and 4 (all stereoisomers), bioassay data, and taxonomic characterization. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Dravid SM, Murray TF. Brain Res. 2004;1006:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Pereira A, Cao Z, Murray TF, Gerwick WH. Chem. Biol. 2009;16:893–906. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Soria-Mercado IE, Pereira A, Cao Z, Murray TF, Gerwick WH. Org. Lett. 2009;11:4704–4707. doi: 10.1021/ol901438b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Taniguchi M, Nunnery JK, Engene N, Esquenazi E, Byrum T, Dorrestein PC, Gerwick WH. J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:393–398. doi: 10.1021/np900428h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dravid SM, Baden DG, Murray TF. J. Neurochem. 2004;89:739–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02407.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berman FW, Murray TF. J. Neurochem. 2000;74:1443–1451. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0741443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi DW. Neuron. 1998;1:623–634. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi DW. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1994;747:162–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb44407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi DW. J. Neurobiol. 1992;23:1261–1276. doi: 10.1002/neu.480230915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marine Natural Products Bibliography Software. Christchurch, New Zealand: University of Cantenbury; 2010. Identification of this substructure facilitated dereplication efforts because only a handful of cyanobacterial-derived secondary metabolites possess such a structural feature, according to MarinLit. (update March 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsumori N, Kaneno D, Murata M, Nakamura H, Tachibana K. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:866–876. doi: 10.1021/jo981810k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uhrin D, Batta G, Hruby VJ, Barlow PN, Kover KE. J. Magn. Reson. 1998;130:155–161. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1997.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williamson RT, Marquez BL, Gerwick WH, Kover KE. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2000;38:265–273. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohtani I, Kusumi T, Kashman Y, Kakisawa H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:4092–4096. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagai Y, Kusumi T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:1853–1856. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Klein D, Braeckman JC, Daloze D. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:7519–7520. [Google Scholar]; (b) Klein D, Braeckman JC, Daloze D, Hoffmann L, Castillo G, Demoulin V. J. Nat. Prod. 1999;62:934–936. doi: 10.1021/np9900324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Matthew S, Salvador LA, Schupp PJ, Paul VJ, Luesch H. J. Nat. Prod. [Online early access]. DOI: 10.1021/np1004032. Published online: August 12, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.This biogenetic dissection is also applicable to the laingolides which are of related structure to 1.

- 16.Grindberg RV, Ishoey T, Brinza D, Esquenazi E, Liu W, Coates RC, Gerwick L, Dorrestein P, Pevzner P, Lasken R, Gerwick WH. (in preparation) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geders TW, Gu L, Mowers JC, Liu H, Gerwick WH, Hakansson K, Sherman DH, Smith JL. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:35954–35963. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703921200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramaswamy AV, Sorrels CM, Gerwick WH. J. Nat. Prod. 2007;70:1977–1986. doi: 10.1021/np0704250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.