Abstract

Cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) are found in the sera of many HIV-1–infected individuals, but the virologic basis of their neutralization remains poorly understood. We used knowledge of HIV-1 envelope structure to develop antigenically resurfaced glycoproteins specific for the structurally conserved site of initial CD4 receptor binding. These probes were used to identify sera with NAbs to the CD4-binding site (CD4bs) and to isolate individual B cells from such an HIV-1–infected donor. By expressing immunoglobulin genes from individual cells, we identified three monoclonal antibodies, including a pair of somatic variants that neutralized over 90% of circulating HIV-1 isolates. Exceptionally broad HIV-1 neutralization can be achieved with individual antibodies targeted to the functionally conserved CD4bs of glycoprotein 120, an important insight for future HIV-1 vaccine design.

Having crossed from chimpanzees to humans in only the past century, HIV-1 has rapidly evolved a daunting degree of diversity, posing a considerable challenge for vaccine development. The definition of naturally occurring broadly neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) has proven elusive, and the ability to target conserved determinants of the viral envelope (Env) has proven difficult (1, 2). During HIV-1 infection, almost all individuals produce antibodies to Env, but only a small fraction can neutralize the virus (1, 2). Recently, several groups have shown that the sera of 10 to 25% of infected participants contain broadly reactive NAbs (3–6), including some sera that neutralize the majority of viruses from diverse genetic subtypes (5–7). NAbs react with the HIV-1 Env spike, which is composed of three heavily glycosylated glycoprotein (gp)120 molecules, each noncovalently associated with a transmembrane gp41 molecule. To initiate viral entry into cells, the gp120 binds to the cell surface receptor CD4 (8). We previously reported that selected sera contain NAbs directed against the CD4-binding site (CD4bs) of gp120 (7, 9), and we defined the structure of the CD4bs in complex with the neutralizing monoclonal antibody (mAb) b12 (10, 11). Antibody b12 was isolated from a phage display library in 1992 and can neutralize about 40% of known HIV-1 isolates (12–14). The more recently isolated CD4bs mAb HJ16 also neutralizes about 40% of viral isolates (15). Attempts to isolate more broadly reactive CD4bs-directed NAbs from human B cells have not met with success, in part because the gp120 or gp140 proteins used were reactive with many HIV-1–specific antibodies, including nonneutralizing antibody specificities (15, 16). In this study, we used our knowledge of Env structure, together with computer-assisted protein design, to define recombinant forms of HIV-1 Env that specifically interact with NAb directed to the CD4bs. These Env probes were used to identify and sort individual B cells expressing CD4bs antibodies, enabling the selective isolation of CD4bs-directed mAbs with extensive neutralization breadth.

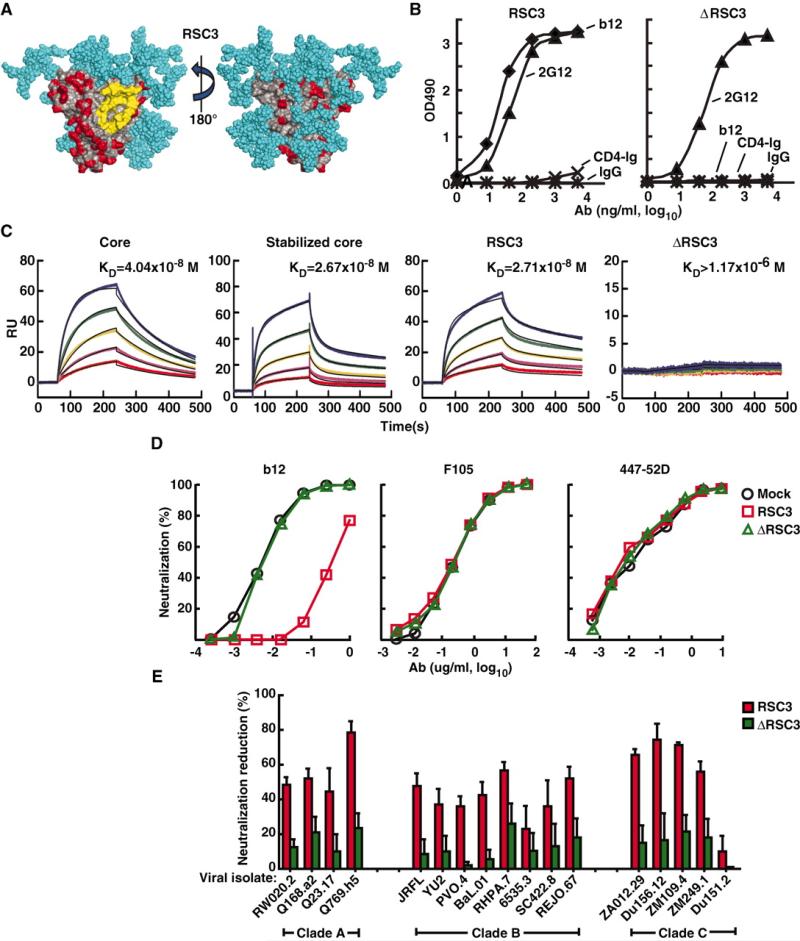

To generate a molecule that preserved the antigenic structure of the neutralizing surface of the CD4bs but eliminated other antigenic regions of HIV-1, we designed proteins whose exposed surface residues were substituted with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) homologs and other non–HIV-1 residues (17) (Fig. 1A and fig. S1). These changes were conferred on a core gp120 and a stabilized core gp120, both of which retained the major contact surface for CD4 located on its outer domain (10, 11, 18). The gp120 core lacked variable regions 1 to 3 and part of the amino and carboxy termini of the full gp120 molecule, and the stabilized core contained cross-links between different subregions of the core protein. Eight resurfaced proteins were designed and expressed, together with CD4bs mutants that served as negative controls by eliminating binding to the neutralizing mAb b12. Three resur-faced core Envs retained strong reactivity with b12 and mAb 2G12 (fig. S2), the latter of which recognizes a surface glycan epitope and served as a positive control for a conformationally intact protein. The resurfaced stabilized core 3 (RSC3) was chosen as the preferred candidate for further studies, because a greater percentage of its surface other than the outer domain CD4bs area was altered compared with the other variants (fig. S2). The conformational integrity and specificity of the RSC3 protein was confirmed by using a panel of known mAbs (table S1). As expected, RSC3 displayed strong reactivity to mAb b12 and little or no reactivity to a CD4 fusion protein (Fig. 1, B and C) (19). RSC3 also reacted with two weakly neutralizing CD4bs mAbs, b13 and m18, but it displayed no reactivity to four CD4bs mAbs that do not neutralize primary HIV-1 isolates, nor with mAbs directed to other regions of the HIV-1 Env, including the coreceptor-binding region of gp120 and the V3 and C5 regions of gp120 (table S1). ΔRSC3, which lacked a single amino acid at position 371 that eliminated b12 binding, served as a negative control. Together, these data confirmed the integrity of the antibody binding surface of this resurfaced protein, and it was used for analyses of sera and to identify B cells from an HIV-1–infected individual whose sera contained broadly reactive NAbs.

Fig. 1.

Design and antigenic profile of RSC3 and analysis of epitope-specific neutralization. (A) Surface structure model of the RSC3. The outer domain contact site for CD4 is highlighted in yellow. Regions highlighted in red are antigenically resurfaced areas, shown on both the inner (left) and outer (right) faces of the core protein. Glycans are shown in light blue. (B) Antigenicity of the RSC3 protein based on ELISA using the neutralizing CD4bs mAb b12 and CD4-Ig fusion protein. mAb 2G12 was used to confirm the structural integrity of the protein. OD indicates optical density. IgG, irrelevant IgG. (C) mAb b12 was immobilized on the sensor chip for SPR kinetic binding analysis with the proteins shown. RU, resonance units. (D) RSC3 blockade of HIV-1 viral strain HXB2 neutralization by the broadly neutralizing CD4bs mAb b12 but not mAb F105, which recognizes the CD4bs differently and has limited neutralization breadth. The V3-neutralizing mAb 447-52D is shown as a control. (E) Analysis of serum 45 neutralization of a panel of 17 viruses, using RSC3 and ΔRSC3 to block neutralization activity. The percent reduction in the serum 50% inhibitory dilution (ID50) caused by competition with RSC3 or ΔRSC3 is shown on the y axis (±SEM of three independent experiments). Viral strains and clades are shown on the x axis. Values less than 20% are not considered significant in this assay.

We screened a panel of broadly neutralizing sera for the presence of antibodies that could preferentially bind to RSC3 compared with ΔRSC3. CD4bs antibodies were detected in several sera, including serum from donor 45, which was previously reported to contain NAbs directed to the CD4bs of gp120 (fig. S3) (7). To determine whether antibodies that bind to RSC3 were responsible for the broad neutralization mediated by serum 45, we performed neutralization studies by using RSC3 to compete cognate antibodies. The utility of this assay was confirmed with the CD4bs mAb b12 and with mAb F105, which binds differently to the CD4bs and does not bind RSC3 (table S1). mAb b12 neutralizes many primary HIV-1 strains, whereas F105 neutralizes mainly laboratory-adapted or other highly sensitive virus strains, such as the HXB2 strain used here. The addition of RSC3 but not ΔRSC3 inhibited b12-mediated neutralization of HXB2. RSC3 had no effect on F105 neutralization, and neither RSC3 nor ΔRSC3 affected neutralization by the anti-V3 mAb 447-52D (Fig. 1D). To interrogate serum 45 neutralization, we performed similar RSC3 competition studies with this serum against a panel of diverse HIV-1 strains (Fig. 1E). This analysis suggested that serum 45 neutralization was principally directed against the CD4bs on functional viral spikes and that the RSC3 faithfully mimicked this structure.

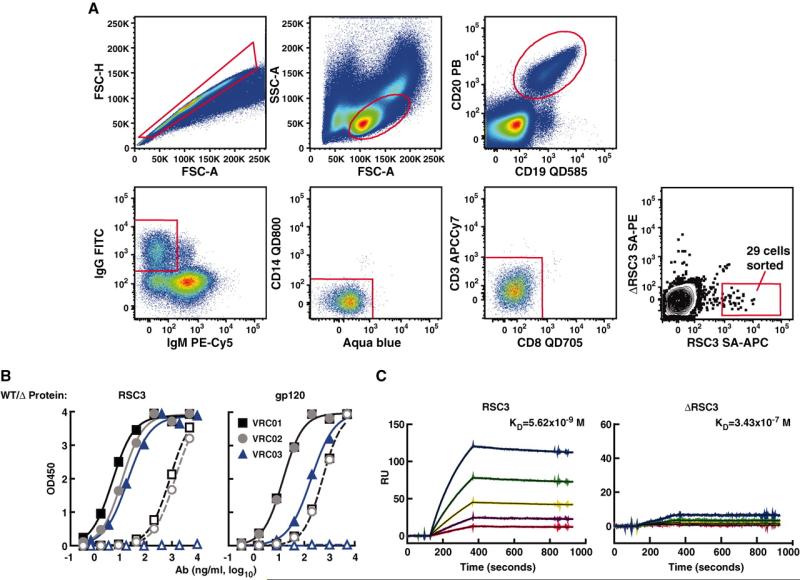

To isolate CD4bs-directed mAbs, we used a recently described method of antigen-specific memory B cell sorting (16), together with single-cell polymerase chain reaction (PCR), to amplify immunoglobulin G (IgG) heavy- and light-chain genes from the cDNA of individual B cells (16, 20). RSC3 and ΔRSC3 were expressed with a tagged amino acid sequence that allows biotin labeling. The two proteins could thus be distinguished by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis after labeling with streptavidin (SA) conjugated to the fluorochromes allophycocyanin (SA-APC) or phycoerythrin (SA-PE), respectively. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from donor 45 were incubated with RSC3 SA-APC and DRSC3 SA-PE, and single antigen-specific memory B cells were sorted into wells of a microtiter plate after selecting for memory B cells (CD19+, CD20+, and IgG+) that bound to the RSC3 but not the ΔRSC3 probe (Fig. 2A). Out of about 25 million PBMC, 29 single RSC3-specific memory B cells were sorted, and the matching heavy- and light-chain genes were successfully amplified from 12 cells. After cloning into IgG1 expression vectors that reconstituted the heavy- and light-chain constant regions, the full IgG mAbs were expressed. Three antibodies (VRC01, VRC02, and VRC03) bound strongly to RSC3 and weakly or not at all to ΔRSC3 (Fig. 2, B, left, and C, and fig. S4). To confirm the specificity of these antibodies for the CD4bs, we tested enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) binding of each mAb against a wild-type gp120 and the CD4bs-defective Asp368→Arg368 (D368R) mutant (Fig. 2B, right). VRC01 and VRC02 bound with ≥100-fold lower relative affinity to the heavy chain variable gene (VH) D368R mutant compared with wild-type gp120, and VRC03 showed no detectable binding to the CD4bs knockout mutant. The ELISA binding profile to an extended panel of mutant Env proteins further confirmed the CD4bs specificity of VRC01, VRC02, and VRC03 (table S1).

Fig. 2.

Isolation of individual CD4bs-directed memory B cells by cell sorting and binding characterization of isolated mAbs. (A) Twenty-five million PBMC from donor 45 were incubated with biotin-labeled RSC3 and ΔRSC3 that were complexed with SA-APC and SA-PE, respectively. Memory B cells were selected on the basis of the presented gating strategy. Twenty-nine B cells that reacted with RSC3 and not ΔRSC3 (representing 0.05% of all memory B cells) were sorted into individual wells of a 96-well plate containing lysis buffer. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate. FSC-H, forward scatter height; FSC-A, forward scatter area; and SSC, side scatter area. (B) ELISA antigen binding profile of three isolated mAbs, VRC01, VRC02, and VRC03. Solid symbols show mAb binding to RSC3 (left) and YU2 gp120 (right). Open symbols indicate binding to ΔRSC3 (left) or to the CD4bs knockout mutant of gp120, D368R (right). WT, wild type. (C) SPR binding analysis of VRC01 reacted with RSC3 and ΔRSC3. VRC01 was captured with an antibody against human IgG-Fc that was immobilized on the sensor chip. The SPR and ELISA data shown are from a representative experiment; several additional assays produced similar data.

Analysis of the heavy- and light-chain nucleotide sequences using JoinSolver software (http://joinsolver.niaid.nih.gov/) and the Immunogenetics Information System (IMGT) database (http://imgt.cines.fr/) revealed that VRC01 and VRC02 were somatic variants of the same IgG1 clone. The heavy-chain CDR3 region of both mAbs was composed of the same 14 amino acids (fig. S5), and both mAbs were highly somatically mutated, with 32% of the heavy chain variable gene (VH) and 17 to 19% of the kappa light chain variable gene (VK) nucleotides divergent from putative germline gene sequences. VRC03 was potentially derived from a different IgG1 clone, but its heavy chain was derived from the same IGHV1-02*02 and IGHJ1*01 alleles as VRC01 and VRC02. VRC03 was also highly somatically mutated, with an unusual seven–amino acid insertion in heavy-chain framework 3 and 30% of VH and 20% of VK nucleotides divergent from putative germline gene sequences. The heavy-chain CDR3 of VRC03 contained 16 amino acids. All three mAbs share common sequence motifs in heavy-chain CDR1, CDR2, and CDR3.

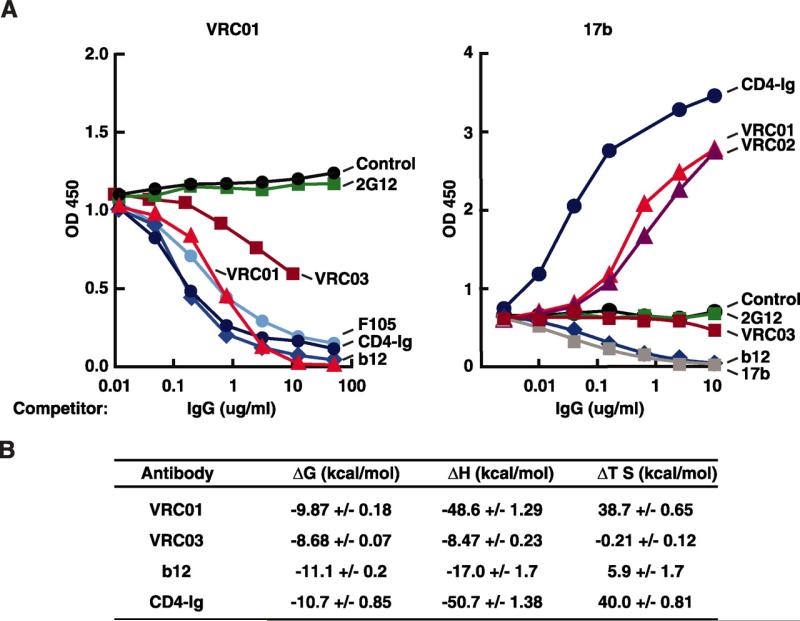

The binding characteristics of the mAbs were further analyzed by surface plasmon resonance (SPR), competition ELISA, and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). SPR demonstrated that VRC01 (KD = 3.88 × 10–9 M) and VRC02 (KD = 1.11 × 10–8 M) bound gp120 with high affinity whereas VRC03 reacted with about 10-fold lower affinity (KD = 7.31 × 10–8 M) (fig. S4). To evaluate the epitope reactivity of these mAbs on gp120, we performed competition ELISAs with a panel of well-characterized mAbs. As expected, binding by all three VRC mAbs was competed by CD4bs mAbs b12 and F105 and by CD4-Ig (Fig. 3A left and fig. S6A). Unexpectedly, the binding of mAb 17b to its site in the coreceptor binding region of gp120 was markedly enhanced by the addition of VRC01 or VRC02 (Fig. 3A right). This enhancing effect was similar, although not as profound, as the known effect of CD4-Ig. In contrast, mAb b12 inhibited mAb 17b binding (Fig. 3A right), as previously shown (21). A similar enhancing result was observed for VRC01 in an assay that measures gp120 binding to its CCR5 coreceptor (fig. S6C). Thus, VRC01 and VRC02 act as partial CD4 agonists in their interaction with gp120, whereas VRC03 does not display this effect. Thermodynamic analysis by ITC provided data consistent with the ELISA results and demonstrated a change in enthalpy (–ΔH) associated with the VRC01-gp120 interaction that was similar to the interaction of CD4-Ig and gp120 (Fig. 3B), further demonstrating that VRC01 binding induced conformational changes in gp120. In contrast to the data for gp120 binding, VRC01 did not enhance viral neutralization by mAb 17b (fig. S7). These data suggest that VRC01 and VRC02 partially mimic the interaction of CD4 with gp120. This may explain their broad reactivity, because essentially all HIV-1 isolates must engage CD4 for cell entry.

Fig. 3.

Antigenic and biophysical characterization of novel CD4bs-directed mAbs. (A) Competition ELISA performed with a single concentration of biotin-labeled VRC01 (left) or the co-receptor binding site mAb 17b (right). The mAbs indicated near each line were titrated into the ELISA at increasing concentrations to evaluate the effect on VRC01 and 17b binding, respectively. The results shown are from a representative experiment; two additional assays produced similar data. (B) ITC to assess the change in enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (–TΔS) upon binding of mAbs to YU2 gp120. Each measured value is shown ±SEM.

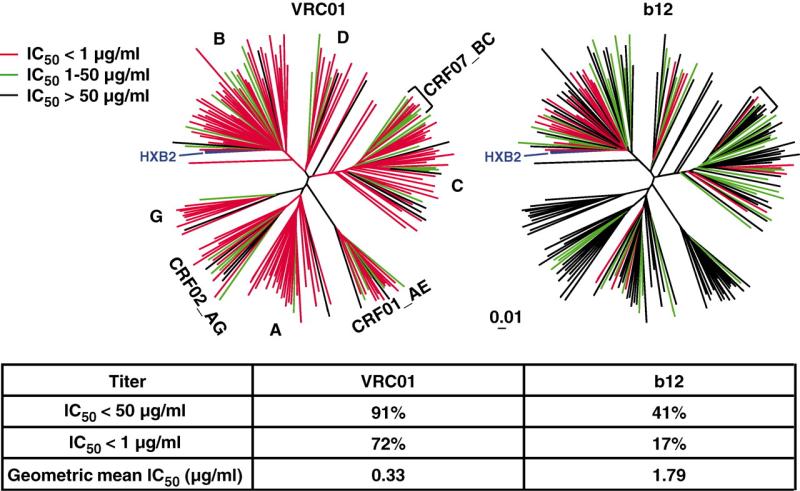

The potency and breadth of neutralization by VRC01, VRC02, and VRC03, compared with those by b12 and CD4-Ig, were assessed on a comprehensive panel of Env pseudoviruses (Fig. 4 and table S2). These 190 viral strains represented all major circulating HIV-1 genetic subtypes (clades) and included viruses derived from acute and chronic stages of HIV-1 infection (22, 23). VRC01 neutralized 91% of these viruses with a geometric mean value of 0.33 μg/ml (Fig. 4 and table S2). The data for VRC02 were very similar (table S2). Of note, these mAbs were derived from an HIV-1 clade B–infected donor yet displayed neutralization activity against all genetic subtypes of HIV-1. VRC03 was less broad than VRC01 and VRC02, neutralizing 57% of the viruses (table S2) (24). In contrast, b12, also derived from a clade B-infected donor, neutralized 41% of viruses tested. Because VRC01 was derived from a donor whose sera was also broadly neutralizing, we assessed the relationship between the neutralization breadth and potency of serum 45 IgG and mAb VRC01. Among 140 viruses tested, there was a significant association (P = 0.005; Fisher's exact test) between the number of viruses neutralized by serum 45 IgG and the number neutralized by VRC01 (fig. S8A). Among the 122 viruses neutralized by both serum IgG and VRC01, there was a strong association (P < 0.0001; Deming linear regression) between the neutralization potency of the serum IgG and the potency of VRC01 (fig. S8B). Therefore, although VRC01 did not account for all serum 45 IgG neutralization, the VRC01-like antibody specificity largely accounts for the extensive breadth and potency of serum 45. These findings demonstrate that a focused B cell response can target a highly conserved region of the HIV-1 Env in humans (25).

Fig. 4.

Analysis of neutralization by mAbs VRC01 and b12 against a panel of 190 Env pseudoviruses representing all major circulating clades of HIV-1. Dendrograms, made by the neighbor-joining method, show the protein distance of gp160 sequences from 190 HIV-1 primary isolates. The clade B reference strain HXB2 was used to root the tree, and the amino acid distance scale is indicated with a value of 1% distance as shown. The clades of HIV-1 main group, including circulating recombinant forms (CRFs), are indicated. Neutralization potency of VRC01 and b12 is indicated by the color of the branch for each virus. The data under the dendrograms show the percent of viruses neutralized with a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50)<50 μg/ml and <1 μg/ml and the geometric mean IC50 value for viruses neutralized with an IC50 <50 μg/ml.

Other mAbs are able to neutralize HIV-1, but none has a profile of potency and breadth similar to VRC01 and VRC02 (1, 13, 14, 26, 27). Antibody 4E10 requires relatively high concentrations to neutralize primary strains of HIV-1 (13), and it neutralizes only 12% of Env-pseudoviruses at a concentration of less than 1 μg/ml (14). The well-characterized CD4bs mAb b12 (13, 14) and the more recently described HJ16 (15) are informative with respect to antigen recognition, but each display restricted breadth (~40% of HIV-1 strains). Recently, two broadly neutralizing somatic variant mAbs, PG16 and PG9, were isolated by high-throughput neutralization screening of B cell supernatants (14). The PG16 and PG9 neutralized 73% and 79%, respectively, of viruses tested and recognized a glycosylated region of HIV-1 Env that is present on the native viral trimer, but this epitope is not well presented on gp120 or gp140.

VRC01 and VRC02 access the CD4bs region of gp120 in a manner that partially mimics the interaction of CD4 with gp120 (28). This observation may explain their impressive breadth of reactivity. The isolation of these mAbs from an HIV-1–infected donor and the demonstration that they neutralize the vast majority of HIV-1 strains by targeting the functionally conserved receptor binding region of Env provides proof of concept that such antibodies can be elicited in humans. The discovery of these mAbs provides new insights into how the human immune system is able to effectively target a vulnerable site on the viral Env.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/science.1187659/DC1 Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S8

Tables S1 to S3

References

References and Notes

- 1.Pantophlet R, Burton DR. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2006;24:739. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montefiori DC, Morris L, Ferrari G, Mascola JR. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS. 2007;2:169. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3280ef691e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stamatatos L, Morris L, Burton DR, Mascola JR. Nat. Med. 2009;15:866. doi: 10.1038/nm.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sather DN, et al. J. Virol. 2009;83:757. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02036-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simek MD, et al. J. Virol. 2009;83:7337. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00110-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doria-Rose NA, et al. J. Virol. 2010;84:1631. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01482-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, et al. Nat. Med. 2007;13:1032. doi: 10.1038/nm1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wyatt R, et al. Nature. 1998;393:705. doi: 10.1038/31514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y, et al. J. Virol. 2009;83:1045. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01992-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwong PD, et al. Nature. 1998;393:648. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou T, et al. Nature. 2007;445:732. doi: 10.1038/nature05580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burton DR, et al. Science. 1994;266:1024. doi: 10.1126/science.7973652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Binley JM, et al. J. Virol. 2004;78:13232. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.13232-13252.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker LM, et al. Science. 2009;326:285. doi: 10.1126/science.1178746. published online 3 September 2009 (10.1126/science.1178746) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corti D, et al. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e8805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scheid JF, et al. Nature. 2009;458:636. doi: 10.1038/nature07930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 18.Dey B, et al. J. Virol. 2007;81:5579. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02500-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The CD4 binding property of the core proteins would result in their binding to circulating CD4-expressing cells, such as CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood. Because this interaction would confound the selection of B cells expressing CD4bs IgG, we additionally sought to design proteins containing the majority of the CD4bs epitope surface that maintained b12 reactivity but that no longer bound to CD4. Specifically, computer-assisted modeling was used to alter the β20/21 region of gp120 that is required for CD4 binding but is not part of the b12-contact surface (fig. S1).

- 20.Wrammert J, et al. Nature. 2008;453:667. doi: 10.1038/nature06890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore JP, Sodroski J. J. Virol. 1996;70:1863. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1863-1872.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korber B, Gnanakaran S. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS. 2009;4:408. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32832f129e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seaman MS, et al. J. Virol. 2010;84:1439. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02108-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Additional studies using primary PBMC-derived viral isolates and PBMC as target cells confirmed that VRC01, VRC02, and VRC03 were able to neutralize replication-competent uncloned HIV-1 isolates grown in primary T cells (table S3). We also tested the impact of VRC01 on the functional viral spike because VRC01 and VRC02, like CD4, showed the ability to alter the conformation of gp120 and enhanced binding of CD4-induced antibodies like 17b. Unlike CD4, however, VRC01 did not promote the entry of primary HIV-1 isolates into CD4-negative cells, and it did not augment the neutralization potency of mAb 17b (fig. S7).

- 25.Our successful isolation of CD4bs mAbs with extensive neutralization breadth was likely due to several factors. Recent advances in high-throughput neutralization assays facilitated the identification of HIV-1 antisera containing broad NAbs (4–7, 29–32). Advances in serum epitope mapping technologies led us to understand that conserved regions of HIV-1 Env may be targeted by such NAbs (4, 7, 9, 30, 33–37). The atomic-level structure of gp120 (10, 38) and advances in computational modeling allowed development of the RSC probe pair that was used to identify and sort CD4bs antibody-secreting B cells. Because of the large repertoire of circulating antibodies against gp120, most of them nonneutralizing, the epitope selectivity conferred by the RSC3 protein, together with use of the knock-out mutant, was likely important for the identification of the relatively rare memory B cells secreting NAbs to the CD4bs. Recently, the gp140 form of Env was used to identify HIV-1–specific B cells and study the repertoire of the antibody responses to the Env glycoprotein (16). Numerous unique antibodies were derived from each of six HIV-1–infected donors, but no single mAb demonstrated broad and potent neutralization. The ability to identify epitope-specific B cells, and isolate the specific IgG clones, has broad potential application. A similar epitope-specific approach could be used to isolate mAbs to sites of known structure from infectious disease pathogens, including tuberculosis and malaria, and can be applied to the identification of targets of autoimmunity or cancer therapy.

- 26.Zolla-Pazner S. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4:199. doi: 10.1038/nri1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forsman A, et al. J. Virol. 2008;82:12069. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01379-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Unlike CD4, VRC01 and VRC02 do not appear to require interaction with the conformationally mobile β20/21 region of gp120, because this region was altered in the RSC3 protein.

- 29.Deeks SG, et al. J. Virol. 2006;80:6155. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00093-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gray ES, et al. J. Virol. 2009;83:8925. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00758-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith DM, et al. Virology. 2006;355:1. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richman DD, Wrin T, Little SJ, Petropoulos CJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:4144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630530100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Binley JM, et al. J. Virol. 2008;82:11651. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01762-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yuste E, et al. J. Virol. 2006;80:3030. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.3030-3041.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dhillon AK, et al. J. Virol. 2007;81:6548. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02749-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Decker JM, et al. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:1407. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shen X, et al. J. Virol. 2009;83:3617. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02631-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen B, et al. Nature. 2005;433:834. doi: 10.1038/nature03327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Vaccine Research Center, the Division of Clinical Research and the Laboratory of Immunoregulation of National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH. M.S.S. was supported in part by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation's Collaboration for AIDS Vaccine Discovery, Comprehensive Antibody-Vaccine Immune Monitoring Consortium, grant number 38619. W.R.S. was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Collaboration for AIDS Vaccine Discovery through a grant to Seattle Biomedical Research Institute and by the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative. Nucleotide sequences of VRC01, VRC02, and VRC03 variable regions are available under GenBank accession numbers GU980702 to GU980707. Patent applications have been filed by the NIH on mAbs VRC01, VRC02, and VRC03 (listed investigators are X.W., Z.Y.Y., Y.L., C.M.H, W.R.S., T.Z., M.C., P.D.K., M.R., R.T.W., G.J.N., and J.R.M.) and on the RSC3 probe (listed investigators are Z.Y.Y., W.R.S., T.Z., P.D.K. and G.J.N.). We thank M. Nussenzweig and J. Scheid (Laboratory of Molecular Immunology, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Rockefeller University, New York, NY) for sharing expertise and reagents for IgG cloning and expression; B. Haynes (Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC) for sharing reagents and PCR methods; S. Perfetto, R. Nguyen, and D. Ambrozak for assistance with cell sorting; E. Lybarger for neutralization assays; J. Stuckey and B. Hartman for assistance with figures; A. Tislerics for manuscript preparation; D. Follman for statistical advice; C. Carrico for discussions on resurfacing; Y.-E. A. Ban and L. Kong for glycan modeling; P. Chattopadhyay and J. Yu for fluorescent antibody production and qualification; C. Williamson (University of Capetown, Capetown, South Africa), M. Thomson (Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain), J. Overbaugh (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA), and S. Tovanabutra and E. Sanders-Buell (Henry M. Jackson Foundation and the U.S. Military HIV Research Program, Rockville, MD) for contributing HIV-1 Env plasmids for pseudovirus production.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.