Abstract

To inform future efforts in tendon/ligament tissue engineering, our laboratory has developed a well-controlled model system with the ability to alter both external tensile loading parameters and local biochemical cues to better understand marrow stromal cell differentiation in response to both stimuli concurrently. In particular, the synthetic, poly(ethylene glycol)-based hydrogel material oligo(poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate) (OPF) has been explored as a cell carrier for this system. This biomaterial can be tailored to present covalently incorporated bioactive moieties and can be loaded in our custom cyclic tensile bioreactor for up to 28 days with no loss of material integrity. Human marrow stromal cells encapsulated in these OPF hydrogels were cultured (21 days) under cyclic tensile strain (10%, 1 Hz, 3 h of strain followed by 3 h without) or at 0% strain. No difference was observed in cell number due to mechanical stimulation or across time (n = 4), with cells remaining viable (n = 4) through 21 days. Cyclic strain significantly upregulated all tendon/ligament fibroblastic genes examined (collagen I, collagen III, and tenascin-C) by day 21 (n ≥ 6), whereas genes for other pathways (osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic) did not increase. After 21 days, the presence of collagen I and tenascin-C was observed via immunostaining (n = 2). This study demonstrates the utility of this hydrogel/bioreactor system as a versatile, yet well-controlled, model environment to study marrow stromal cell differentiation toward the tendon/ligament phenotype under a variety of conditions.

Introduction

Over 800,000 people seek medical attention each year for injuries to ligaments, tendons, or the joint capsule.1 Tendon and ligament tissues, composed of collagen bundles organized in a hierarchical fashion, function primarily in tension to induce or guide joint movement.2 Fibroblasts maintain this extracellular matrix (ECM), but their low cell numbers and low mitotic activity lead to a reduced tissue turnover rate that may explain the poor natural healing of some tendons and ligaments.3 While tissue grafts can improve function after injury, current graft fixation procedures do not completely recapitulate normal joint mechanics, leading to potential for secondary pathologies such as osteoarthritis.4 Thus, there is a need for new regenerative medicine-based strategies to improve healing of tendon/ligament injuries and provide alternatives to current autograft transplantation techniques.

Over the past 15 years, a variety of tissue engineering approaches have been explored for tendon and ligament regeneration. Many of these center on combining cells with a three-dimensional biomaterial scaffold,5,6 and may also add exogenous bioactive factors, such as growth factors or mechanical (usually tensile) stimulation.6–8 Progenitor cells, such as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), are often selected as the cell source for these studies6,9 since this overcomes the difficulty of isolating autologous tendon/ligament fibroblasts in sufficient numbers to seed on scaffolds for eventual clinical applications.10 MSCs can be expanded many times11 and subsequently differentiate into multiple lineages associated with orthopedic tissues, including tendon/ligament fibroblasts.12 In addition, this flexibility provides the future possibility of using a single cell source to form all the tissues associated with tendon/ligaments and their insertions to bone/muscle, and thus potentially provides a true counterpart to the bone–ligament–bone autografts currently employed in reconstruction procedures.13 However, optimization of MSC differentiation to tendon/ligament fibroblasts for these applications has been hampered by lack of knowledge of how both loading and biochemical cues simultaneously regulate this process. We have therefore developed a well-controlled model system with the ability to alter both external loading parameters and local extracellular cues to better study MSC response to both stimuli concurrently.

Our laboratory is exploring the synthetic, poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-based material OPF as a cell carrier in such a model system. Previous work in tendon/ligament tissue engineering has involved the use of both synthetic5,14 and natural6,8,15,16 materials as scaffolds for tensile culture studies. One advantage of this cytocompatible17 hydrogel over many other scaffolds is the ease with which bioactive moieties can be covalently incorporated into the hydrogel matrix in a controlled manner.18 Another novel attribute is the ability to create layered OPF hydrogels with robust interfaces (Fig. 1B and C).19 This trait facilitates coculture with diverse cell types and/or varied biomaterial environments to better understand cellular differentiation in a complex environment such as that found at the ligament/tendon–bone or tendon–muscle interface.

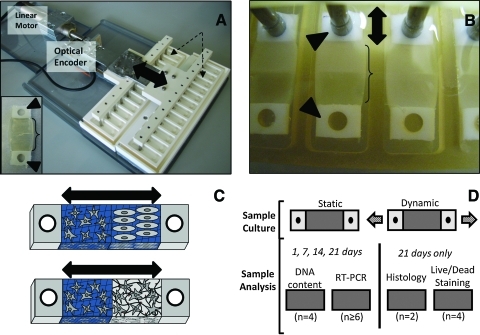

FIG. 1.

(A) Custom tensile culture system. Up to 24 biomaterial constructs can be cultured in tensile wells (dotted-line arrows) and strained by the tensile rakes (double-head arrow shows direction of tensile strain) at the same time. The rake is moved by a linear motor with positional accuracy monitored by an optical encoder. Inset: individual construct with hydrogel (bracket) flanked by end blocks (arrowheads). (B) Laminated hydrogel constructs in culture wells. Polyethylene end blocks (arrowheads) are interfaced with the tensile rake to allow mechanical stimulation to be transduced to the hydrogel section (bracket) and create a uniform strain field in the construct during culture. Double-head arrow indicates direction of strain. (C) Diagram demonstrating possibilities for future use of this culture system with laminated hydrogels. For example, this permits coculture of two different cell types (top) or two biomaterial environments with different bioactive factors (bottom). Double-head arrow represents direction of strain. (D) Overall experimental design for human marrow stromal cell loading studies. Arrows represent direction of loading on dynamic samples. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

For these studies, this OPF-based biomaterial was combined with a custom tensile culture bioreactor (Fig. 1A and B). Tensile strain has been employed to stimulate MSC differentiation toward a tendon/ligament fibroblast phenotype.20 This system has the advantage of being able to develop strains in a three-dimensional environment, which may be important since cells respond differently in two-dimensional compared to three-dimensional culture.21 In addition, the tensile constructs are designed to create a uniform strain field across the hydrogel22 to provide a well-defined mechanical environment.

While the long-term goal is to employ this model system to examine the formation of ligaments/tendons as well as their interfaces with surrounding tissues, a first step was to determine if layered (laminated) acellular OPF hydrogels would withstand cyclic loading over 28 days in vitro. After this was ascertained, differentiation of human marrow stromal cells (hMSCs) encapsulated in nonlaminated OPF hydrogels in response to cyclic tensile loading was examined as a proof of concept before moving to more sophisticated coculture conditions in future experiments. In particular, for these experiments, hMSCs were encapsulated in a mixture of OPF and PEG-diacrylate (PEG-DA) with the tethered adhesive peptide glycine-arginine-glycine-aspartate-serine (GRGDS) using a radical-induced gelation process23 and cultured in a cyclic tensile bioreactor for 21 days. On the basis of previous work with tensile stimulation of MSCs,20,24,25 constructs were cultured under a repeating cyclic strain regimen of 10% strain, 1 Hz, and 3 h of strain followed by 3 h without strain. After days 1, 7, 14, and 21 of culture, cell number, gene expression (particularly collagen I, III, and tenascin-C), and protein production were compared between constructs containing encapsulated hMSCs exposed to tensile stimulation and hMSCs embedded in identical OPF hydrogels without mechanical stimulation to investigate the effects of cyclic tension on cellular differentiation in this hydrogel environment. More specifically, the hypothesis of this study was that cyclic tensile loading would promote a fibroblastic phenotype in encapsulated hMSCs over 21 days of in vitro culture.

Materials and Methods

Polymer synthesis

OPF with a 3 kDa PEG chain (OPF-3K) or a 10 kDa PEG chain (OPF-10K) was synthesized according to previous protocols.26 Briefly, CaH2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was mixed with methylene chloride (MeCl; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and distilled to produce anhydrous MeCl. To produce the OPF polymer, fumaryl chloride (FuCl; Sigma-Aldrich) and triethylamine (TEA; Sigma-Aldrich) were slowly added dropwise to PEG (3 kDa; Mn: 3300 ± 10 Da, propidium iodide: 1.1 or 10 kDa; Mn: 12,400 ± 20 Da, propidium iodide: 1.1; Sigma-Aldrich) that had been azeotropically distilled in toluene (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and dissolved in MeCl. FuCl and TEA were added at ratios of 0.9:1 FuCl:PEG and 1:2 FuCl:TEA under nitrogen gas and cooled over ice. MeCl was removed from the resultant OPF product by rotovapping (Buchi). Recrystallization of the OPF was carried out twice in ethyl acetate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to remove salts produced by the conjugation reaction. Ethyl acetate was removed by three consecutive washes in ethyl ether (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Polymers were vacuum-dried to remove ethyl ether and stored at −20°C before use. The molecular weight of the OPF polymer was determined through gel permeation chromatography (Shimadzu). The resultant OPF-3K polymer was found to have a molecular weight (Mn) of 8900 ± 530 with a polydispersity index of 3.1 ± 0.4 and the OPF-10K had an approximate Mn of 18,300 ± 90 with a polydispersity index of 4.8 ± 0.2. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectra of similar OPF macromers and the number of double bonds present in the macromer has been reported previously.18,26

Peptide conjugation

To allow presentation of RGD ligands to encapsulated cells, the GRGDS adhesion peptide (PeproTech) was conjugated to a 3400 Da MW acrylated-PEG (A-PEG)-succinimidyl valerate spacer (SVA; Laysan Bio) according to previous protocols.18 Briefly, conjugation was achieved by adding the A-PEG-succinimidyl valerate spacer to the GRGDS adhesion peptide dissolved in a sodium bicarbonate (Sigma-Aldrich) buffer solution under gentle stirring over a 3-h period. The mixed solution was transferred into 1000 Da molecular weight cut-off dialysis tubing (Spectrum Laboratories) and dialyzed for 2 days to remove unreacted peptides. Conjugated peptide was then lyophilized (Labconco) and stored at −20°C.

Tensile culture bioreactor

The tensile culture device employed in this study is a modification of one previously used with fibrin hydrogels.27 Major components include a linear motor, optical encoder, tension rakes, and stationary culture chambers (Fig. 1A and B). Movement of the tensile rake is imparted through the linear motor. The linear motor is computer controlled by a user-defined displacement protocol and is monitored through readings of the optical encoder. This system facilitates simultaneous culture of up to 24 constructs in individualized tensile culture wells (Fig. 1B). In addition, the components that interface with the tensile constructs (rakes and culture chambers) can be autoclaved for easy sterilization.

The tensile constructs are fabricated by injecting polymer solutions into a mold between two polyethylene end blocks (75–110 μm pore size; Interstate Specialty). The polymer solution invades the porous end blocks and forms an integrated tensile construct hydrogel after cross-linking. The final tensile construct (Fig. 1A, inset) contains a cell-hydrogel section (12.5 × 9.5 mm, 1.6 mm) flanked by the porous end blocks. One end block is placed over a stationary peg in the culture wells and the other end block interfaces with the tensile rake of this bioreactor (Fig. 1B). The high stiffness of the end blocks compared to the hydrogel allows a uniform strain field to be imparted across the sample during tensile culture.22,27

Hydrogel degradation study

To examine hydrogel degradation under tensile loading, OPF (3K or 10K) and PEG-DA (nominal MW 3400; Laysan Bio) were combined in a 1:1 wt/wt ratio. Polymers suspended (75 wt% liquid) in phosphate-buffered saline with Ca2+ and Mg2+ (PBS; Invitrogen) were injected into a custom-fabricated mold and cross-linked for 10 min at 37°C with 0.018 M of the thermal radical initiators ammonium persulfate (Sigma-Aldrich) and N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine (Sigma-Aldrich). For laminated hydrogels, an OPF-10K solution was injected into one half of the mold and cross-linked for 6 min at 37°C. Subsequently, the OPF-3K solution was injected into the other half of the mold and cross-linked for an additional 6 min to form the laminated construct (seen in Fig. 1B and C). After fabrication, constructs were loaded under a sinusoidal cyclic strain regimen of 10% strain (5% offset, 5% amplitude) at 1 Hz for 12 h, followed by 12 h at 0% strain. After 1, 7, 14, and 28 days of culture, constructs were removed (n ≥ 3). Fold swelling was calculated by Ww/Wd where Ww is the weight of the hydrogel after culture and before drying, and Wd is the weight of the hydrogel after vacuum-drying.

Cell culture

MSCs (PT-2501; Lonza) obtained at passage 0 were seeded into tissue culture flasks at 3333 cells/cm2 and grown in the mesenchymal stem cell growth medium (Lonza). Cells were passaged after reaching ∼80% confluency using a one to three expansion. At passage 5, cells were cryopreserved for future use. The culture medium was changed every 2–3 days. hMSCs from four unique donors were pooled in equal numbers at passage 5 and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 4.5 g/L glucose and sodium pyruvate (Mediatech), 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1% nonessential amino acids (Mediatech), and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic (Mediatech). The medium was changed every 2–3 days. (Note: fetal bovine serum was prescreened for the highest promotion of cell growth and collagen I, collagen III, and tenascin-C gene expression, with cell growth being the primary criteria.) Ascorbic acid (50 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the medium composition described above for the immunohistochemistry studies.

Cell encapsulation in constructs

For experiments involving encapsulated hMSCs, constructs were fabricated from OPF-3K and PEG-DA hydrogel solutions with A-PEG GRGDS adhesion peptide at a concentration of (1 μmol GRGDS)/(g of hydrogel after swelling). After the solutions were filter sterilized using a 0.2 μm filter (Nalgene) hMSCs were added at 10 × 106 cells/mL and the hydrogel solution was cross-linked as described above. After fabrication, the tensile constructs were placed into six-well plates in the culture medium and allowed to swell overnight.

Tensile culture

After equilibrium swelling was achieved, constructs with encapsulated hMSCs were loaded into the tensile culture bioreactor (Fig. 1A and B). A loading regimen for these studies was chosen based on parameters commonly used in tendon/ligament tissue engineering and parameters previously used with this system to promote collagen expression and production.24,25 Specifically, constructs were maintained under a sinusoidal cyclic strain regimen of 10% strain (5% offset, 5% amplitude) at 1 Hz for 3 h, followed by 3 h at 0% strain. Control hydrogels were loaded into a similar culture system, but held at 0% strain. The culture medium was replaced every 2–3 days.

Cell viability

After 21 days of culture, constructs were removed from the device and soaked in PBS for 1 h to remove the medium. After the medium was removed, the hydrogels were incubated in the LIVE/DEAD fluorescent staining solution (1 nM calcein AM and 1 nM ethidium homodimer-1 in PBS; Invitrogen) for 1 h. After staining, hydrogel constructs were removed from the LIVE/DEAD solution and washed in PBS for 10 min to remove excess dye before imaging. Images from the center of each hydrogel were acquired (n = 4, Fig. 1D) using a confocal microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 100M with LSM 510 software).

Cell number

At 1, 7, 14, and 21 days after initiation of mechanical stimulation, constructs were removed from the tensile device and washed in PBS. After washing, the end blocks were removed and the wet weight of the hydrogel was recorded. Hydrogel portions were mechanically disrupted using a pellet grinder (VWR International) and suspended in 750 μL of distilled, deionized water. To disrupt cells and release DNA into solution, samples were subjected to three cycles of freezing at −80°C for 1 h, thawing at room temperature for 30 min, and sonicating for 30 min. DNA content, which can be correlated to cell number, was determined (n = 4, Fig. 1D) by assaying the resulting supernatant via PicoGreen (Invitrogen) with λDNA used for standards (included in kit). The results were normalized to the weight of the hydrogel after culture to account for potential differences in the mass of individual hydrogels.

Gene expression

At 1, 7, 14, and 21 days after initiation of tensile stimulation, constructs were removed from the tensile device for gene expression analysis. After washing with PBS, the end blocks were removed and the hydrogel portion of the construct was mechanically disrupted using a pellet grinder. RNA was isolated from the hydrogels with the QiaShredder column (Qiagen). Purification of RNA was achieved using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized with Superscript III RT (Invitrogen) in the presence of a nucleotide mix (Promega).

Amplification of cDNA through real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction was performed using custom-designed primers and SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems). The process was conducted and recorded using the StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). For statistical analysis, cycle thresholds normalized to glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase were used (n ≥ 6). Genes examined included collagen I, collagen III, and tenascin-C as markers for tendon/ligament fibroblast gene expression.20 To explore the potential for differentiation down alternate pathways, genes from other lineages were examined, including collagen II (chondrogenic differentiation28), osteocalcin (osteoblastic differentiation28), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA, myofibrogenic differentiation29), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma 2 (PPARγ, adipocytic differentiation30). Sequences for the forward and reverse primers used are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers Used for Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| Col I | gaaaacatcccagccaagaa | gccagtctcctcatccatgt |

| Col III | tacggcaatcctgaacttcc | gtgtgtttcgtgcaaccatc |

| TNC | ccacaatggcagatccttct | gttaacgccctgactgtggt |

| Col II | accccaatccagcaaacgtt | atctggacgttggcagtgttg |

| OCN | gtgcagagtccagcaaaggt | agcagagcgacaccctagac |

| α-SMA | gcctgagggaaggtcctaac | ggagctgcttcacaggattc |

| PPARγ2 | tccatgctgttatgggtgaa | gggagtggtcttccattacg |

| GAPDH | gagtcaacggatttggtcgt | ttgattttggagggatctcg |

α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; col I, collagen I; col II, collagen II; col III, collagen III; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase; OCN, osteocalcin; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma 2; TNC, tenascin-C.

Histology

After 21 days, samples cultured in the medium with ascorbic acid were collected for histological staining. After washing in PBS, the end blocks were removed and the hydrogel portion of the construct was held under a −20 mmHg vacuum in optimal cutting temperature compound (VWR International) for 4 h to enhance penetration, then frozen over dry ice, and stored at − 80°C until sectioning. Optimal cutting temperature-embedded hydrogels were cut into 30 μm sections on glass slides. Sections were fixed using acetone and immunohistochemistry was performed for genes that were significantly upregulated in real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (n = 2, Fig. 1D). Primary antibody binding to proteins of interest was accomplished using monoclonal immunoglobulin G mouse anti-human antibodies (Abcam). Secondary antibody binding to primary antibodies was accomplished using polyclonal goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Abcam). Sections were exposed to diaminobenzidine chromogen (Abcam) for 15 min to elicit a color change. Negative controls included samples immunostained with the primary antibody omitted.

Statistics

Results are reported as mean ± standard deviation. A two-way analysis of variance was used to determine statistical significance of groups and Tukey's post hoc test with significance set at p ≤ 0.05 indicated significance between individual samples. For the hydrogel degradation study, the factors were day and hydrogel type. For the cell number study and gene expression analysis, the factors were day and mechanical condition. Statistical analysis was carried out using Systat.

Results

Hydrogel degradation

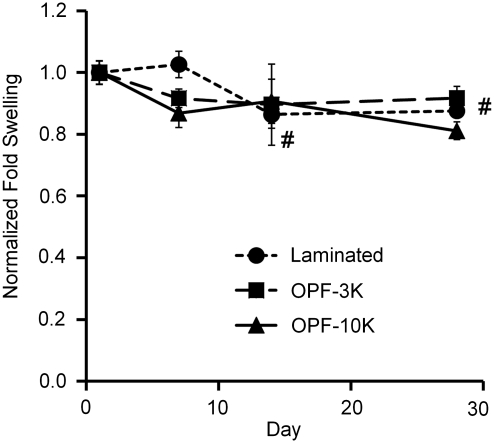

OPF-3K, OPF-10K, and 3K-10K-laminated hydrogels remained well integrated with their end blocks with no visible breaks through 28 days. This is particularly noteworthy because it has been shown in previous work that OPF-10K hydrogels swell significantly more than OPF-3K gels,23 suggesting that the laminated gels were sufficiently bonded to withstand internal pressures generated from differential swelling, as well as strains imparted in tensile culture. Fold swelling of laminated constructs was significantly lower on days 14 and 28 compared to day 1 (Fig. 2); however, there was no significant change in dry weight after 28 days for any construct type (data not shown), indicating no loss of material over time. For further analyses, nonlaminated hydrogels were used to examine the effect of mechanical stimulation on encapsulated hMSCs before more sophisticated laminated cocultures are investigated in future experiments. OPF-3K-based hydrogels were specifically chosen due to their greater ability to facilitate cell adhesion in two-dimensional culture compared to OPF-10K hydrogels (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

OPF-3K, OPF-10K, and laminated hydrogel constructs all maintained structural integrity over 28 days of cyclic tensile culture with minimal degradation (n ≥ 3 ± standard deviation). Fold swelling was normalized to day 1 for each construct type. #Significance difference for laminated constructs versus day 1 (p < 0.05). OPF-3K, oligo(poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate) with a 3 kDa poly(ethylene glycol) chain; OPF-10K, oligo(poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate) with a 10 kDa poly(ethylene glycol) chain.

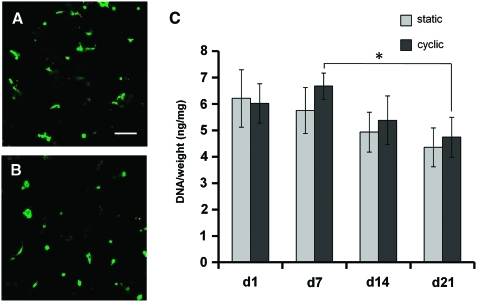

Cell viability and number

Cells in both cyclically (Fig. 3A) and statically (Fig. 3B) cultured hydrogels generally demonstrated green staining, indicating viability. DNA content/hydrogel wet weight (an indicator of cell number per construct) showed no significant differences between samples cultured under cyclic tension compared to those cultured statically (Fig. 3C). Overall, DNA content was relatively constant in both static and cyclic hydrogel constructs over 21 days, with only the comparison between days 7 and 21 cyclic constructs showing significance.

FIG. 3.

A majority of live (green) cells were observed in both cyclically (A) and statically (B) cultured OPF hydrogels over 21 days (n = 4). No significant difference in cell number (C) was found between static conditions and cyclic strain at any time point (n = 4 ± standard deviation). *Significance (p ≤ 0.05). Scale bar = 100 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

Gene expression

No significant difference was seen in mRNA expression between cyclically and statically cultured constructs for the non-tendon/ligament fibroblast genes (collagen II, α-SMA, osteocalcin, and PPARγ—Table 2) at each time point. In addition, collagen II and PPARγ demonstrated no significant differences in expression across time. Similarly, α-SMA expression showed no significant change across time in cyclic samples, although upregulation was seen in static samples on days 14 and 21 compared to day 1. Upregulation was also seen in osteocalcin in both static and cyclic samples on days 14 and 21 compared to day 1.

Table 2.

Relative Gene Expression Levels (Fold Change Vs. Glyceraldehyde Phosphate Dehydrogenase, n ≥ 6 ± Standard Deviation)

| Day 1 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 21 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Col I | ||||

| Static | 1.3 ± 0.12 | 1.3 ± 0.71 | 1.4 ± 0.89 | 2.4 ± 1.1a |

| Cyclic | 1.4 ± 0.33 | 2.8 ± 0.67ab | 2.7 ± 0.92b | 5.4 ± 1.3ab |

| Col III | ||||

| Static | 0.76 ± 0.051 | 0.70 ± 0.46 | 1.2 ± 0.49a | 2.3 ± 1.0a |

| Cyclic | 0.93 ± 0.28 | 1.2 ± 0.26 | 1.9 ± 0.53a | 6.9 ± 1.7ab |

| TNC | ||||

| Static | 0.093 ± 0.032 | 0.26 ± 0.15a | 0.68 ± 0.35a | 0.37 ± 0.12a |

| Cyclic | 0.10 ± 0.025 | 0.40 ± 0.087a | 0.87 ± 0.40a | 1.1 ± 0.40ab |

| Col II | ||||

| Static | 1.7 × 10−5 ± 4.2 × 10−6 | 2.9 × 10−5 ± 2.5 × 10−5 | 6.3 × 10−3 ± 0.010 | 2.2 × 10−4 ± 1.1 × 10−4 |

| Cyclic | 2.5 × 10−5 ± 5.2 × 10−6 | 6.5 × 10−4 ± 1.0 × 10−3 | 1.2 × 10−3 ± 2.1 × 10−3 | 2.3 × 10−4 ± 8.6 × 10−5 |

| α-SMA | ||||

| Static | 1.4 × 10−3 ± 3.9 × 10−4 | 2.2 × 10−3 ± 1.1 × 10−3 | 4.0 × 10−3 ± 1.0 × 10−3a | 3.2 × 10−3 ± 1.7 × 10−3a |

| Cyclic | 1.3 × 10−3 ± 8.3 × 10−4 | 2.1 × 10−3 ± 4.3 × 10−4 | 3.7 × 10−3 ± 2.1 × 10−3 | 3.7 × 10−3 ± 8.2 × 10−4 |

| OCN | ||||

| Static | 2.7 × 10−3 ± 1.1 × 10−3 | 5.5 × 10−3 ± 1.8 × 10−3 | 1.5 × 10−2 ± 8.6 × 10−3a | 8.1 × 10−3 ± 2.8 × 10−3a |

| Cyclic | 3.4 × 10−3 ± 1.0 × 10−3 | 6.7 × 10−3 ± 1.3 × 10−3 | 1.0 × 10−2 ± 3.9 × 10−3a | 9.0 × 10−3 ± 2.1 × 10−3a |

| PPARγ | ||||

| Static | 7.8 × 10−6 ± 2.9 × 10−6 | 4.8 × 10−5 ± 5.6 × 10−5 | 4.4 × 10−5 ± 5.8 × 10−5 | 1.5 × 10−5 ± 1.1 × 10−5 |

| Cyclic | 6.0 × 10−6 ± 4.1 × 10−6 | 1.3 × 10−5 ± 1.6 × 10−5 | 1.2 × 10−4 ± 1.6 × 10−4 | 1.7 × 10−5 ± 2.8 × 10−5 |

Significantly different from day 1 for the same sample type (p ≤ 0.05).

Significantly different from static constructs at same time point (p ≤ 0.05).

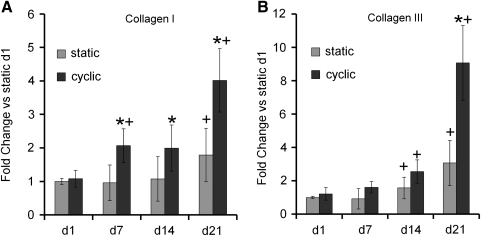

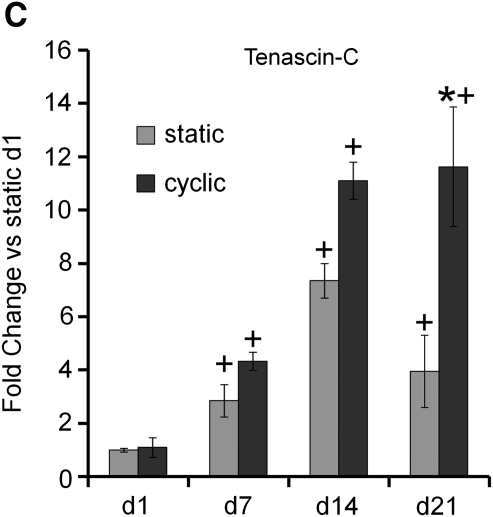

In contrast with non-tendon/ligament fibroblast genes, significant differences were seen for tendon/ligament fibroblast lineage genes between cyclic and static culture, particularly at later time points. Specifically, collagen I mRNA was significantly upregulated in cyclically strained constructs on days 7, 14, and 21 as compared to static constructs, although no difference was observed on day 1 (Fig. 4A). Upregulation of collagen I mRNA was also observed in both strained and static samples at day 21 and in strained samples on day 7 in comparison to day 1. Collagen III mRNA was significantly upregulated in cyclically strained constructs on day 21 as compared to static constructs (Fig. 4B). Upregulation of collagen III mRNA was also observed in both strained and static samples on days 14 and 21 in comparison to day 1. Tenascin-C mRNA was significantly upregulated in cyclically strained constructs on day 21 as compared to static constructs at that time point (Fig. 4C). Upregulation of tenascin-C was also found in both strained and static samples on days 7, 14, and 21 compared to day 1.

FIG. 4.

Collagen I (A), collagen III (B), and tenascin-C (C), markers for tendon/ligament fibroblastic differentiation, were upregulated in human marrow stromal cells encapsulated in constructs under cyclic tensile strain compared to static constructs by day 21 (n ≥ 6 ± standard deviation). Expression normalized to glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase was then normalized to day 1 static results for all genes (note: y-axis is different for each graph). *Significance over static constructs at same time point (p ≤ 0.05). +Significance over day 1 for the same sample type.

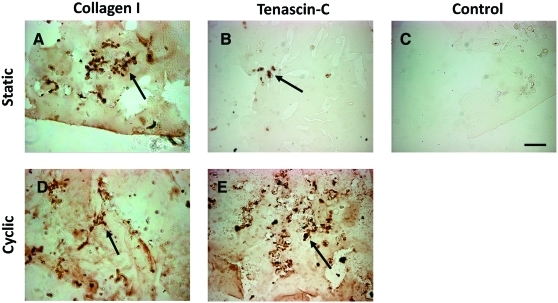

Histology

Immunohistochemistry revealed the presence of collagen I and tenascin-C after 21 days of culture in both static and cyclic constructs (Fig. 5), indicating that gene expression of these tendon/ligament fibroblast markers was translated into protein production in the hydrogel constructs. Occasional staining of collagen III (data not shown) was also detected in samples under cyclic strain, although not consistently. As seen in Figure 5, staining generally appeared to be concentrated pericellularly and tenascin-C seemed to be more prevalent in cyclic constructs. No staining was evident in control sections with the primary antibody omitted.

FIG. 5.

Immunohistochemistry (n = 2) showing the presence of collagen I (A, D) and tenascin-C (B, E) after 21 days of culture in both static and cyclic constructs. Collagen I and tenascin-C were detected mainly pericellularly (arrows). No staining was evident in control sections with the primary antibody omitted (C). Scale bar = 100 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

Discussion

Our three-dimensional OPF hydrogels and novel tensile culture system provide a versatile scaffold–bioreactor system for the study of biological and mechanical influences on cells. The ability to incorporate ECM moieties and create hydrogel laminates that are stable through at least 28 days of cyclic tensile culture (Fig. 2) makes this system ideal for studying the formation of tendons/ligaments as well as their interfaces with muscle/bone. While culture periods longer than 3–4 weeks can lead to hydrolytic degradation of OPF-based hydrogels, minimal degradation was seen in this system after 4 weeks, in agreement with prior reports.31 This afforded an advantage for these studies because no change in loading of the embedded cells could occur due to polymer degradation over the culture period. Similarly, because a synthetic polymer is employed in this system, no alteration in construct geometry (shrinkage) was observed up to 21 days in the presence of cells, as has been reported previously with naturally based polymers.16,32

For these experiments, our custom bioreactor system was used to examine the differentiation of hMSCs in OPF hydrogels modified with RGD adhesion peptides over 21 days of culture. As shown in previous work, cells can detect and adhere to RGD in OPF hydrogels.18 This peptide was employed in these studies to avoid the lowered viability seen with hMSCs in hydrogels without RGD.33 This provided the foundation for a scaffold that would permit cell survival so this study could focus on the effect of cyclic strain on encapsulated cells. As expected, the system demonstrated high cell viability (Fig. 3A and B), with no significant change in cell number between days 1 and 21 constructs in either static or strained conditions (Fig. 3C).

While this study showed no change in cell number due to strain, other groups have reported that strain promotes higher34,35 or lower36,37 cell numbers over time. Cell proliferation in the hydrogels of this study may have been prevented by the small mesh size of these hydrogels. Mesh sizes of between 76 and 160 Å have previously been reported for similar OPF hydrogels19 and sizes ranging from 20 to 60 Å were calculated for PEG-DA hydrogels.38,39 While OPF hydrogel mesh size increases with the molecular weight of the PEG chain, the mesh size of an OPF-10K hydrogel is still orders of magnitude smaller than a cell,19 allowing only limited space for cellular division in the dense polymer matrix. Modifications of the hydrogel environment to facilitate local cell-mediated degradation may be a target for further studies in an effort to provide the void space needed for proliferation inside the gel.

Upregulation of collagen I, collagen III, and tenascin-C gene expression was observed in the constructs, particularly under cyclic loading (Fig. 4). This is in agreement with the findings of previous studies that have used three-dimensional constructs.20,40,41 The upregulation of collagen I, collagen III, and/or tenascin-C mRNA is often used as a marker for a tendon/ligament fibroblast phenotype due to the prevalence of these proteins in tendon/ligament tissue.3,10,42 Collagens make up the majority of tendon/ligament and give the tissue its high tensile strength.2 Tenascin-C is an antiadhesive protein and may increase tissue elasticity in response to heavy loading.43 Other work using collagen I gels to encapsulate hMSCs has shown an upregulation of collagen III, but not collagen I, in response cyclic strain.16 The differences in the response of collagen I may be due in part to variations in the cyclic strain regimen, since the studies that reported upregulation of collagen I in response to cyclic strain employed higher amplitudes and durations of strain.20,40,41 Overall, the upregulation of collagen I, collagen III, and tenascin-C in cyclic constructs compared to static samples by day 21 suggests that, under the loading conditions chosen for this study, cyclic strain promoted a fibroblastic phenotype in hMSCs by 21 days. While some upregulation was seen over time in certain non-tendon/ligament fibroblast genes (Table 2), the lack of upregulation of any of these genes under cyclic conditions suggests that cyclic strain did not promote differentiation down alternative pathways.

Collagen I gene expression in this study correlated with pericellular matrix deposition (Fig. 5A and D), although differences in staining were not apparent between cyclically and statically cultured hydrogels, in contrast with previous results.40 In addition, in our experiments, little collagen III staining was observed at day 21, despite upregulation of collagen III expression levels at this time point. Previous reports have demonstrated collagen III production in response to cyclic strains when marrow stromal cells were cultured in collagen I gels.20,40 However, in these prior studies, the presence of the collagen-based scaffold, as well as differences in the exact loading parameters used, which in some cases applied a combination of translation and rotational forces,20 could have affected the level of deposition of both collagen I and III around the cells. One possible explanation for the minimal collagen III staining in our system is that a large fold change in gene expression was not observed until day 21, and therefore there may not have been enough time to observe increased production of this molecule in this study. While the collagen production seen may indicate that the cells are not following a normal healing response, where collagen III is deposited initially and later replaced by collagen I,44 the results are encouraging since collagen I is more prevalent than collagen III in mature tissue.45 Further work, including studies to examine the time course of collagen production in this system, will be required to better understand and optimize culture conditions to promote optimal ratios of collagen I and collagen III.

Tenascin-C was also observable by immunostaining at day 21, especially in cyclically cultured constructs (Fig. 5B and E). During development, tenascin-C is expressed highly at insertion sites of ligaments and tendons to bone46 and is localized immediately surrounding cells,46 similar to the pericellular staining that was observed. Culture methods that encourage production of both collagen I and tenascin-C, similar to our system, may be promising avenues for pursuit of tissue engineering of insertion sites of ligament and tendon to bone.

One factor that may have played an important role in the distribution and ratios of the proteins produced is the physical constraints imposed by the biomaterial environment. Hydrogels with small mesh sizes and limited degradability, similar to the OPF hydrogels used in this study, have produced a pericellular matrix deposition47 like that observed in this system. In those experiments, degradation of the scaffold led to larger mesh sizes that facilitated a change in the ratio and distribution of matrix proteins, most likely by allowing greater diffusion of the proteins that make up the ECM. Investigation of the effect of PEG-based hydrogels with larger mesh sizes or degradation of the OPF hydrogel matrix may be necessary to facilitate a distribution of matrix proteins throughout the construct as seen in more mature tendon/ligament tissue.46

Conclusions

In addition to confirming the responsiveness of hMSCs to tensile loading, the studies described here demonstrate the feasibility of this novel system in examining cellular differentiation under tensile loading in response to controlled physicochemical changes in the extracellular environment, including the possibility of coculture using the laminated structures tested in these experiments. Significant additional work is required to find the correct combination of cell types, bioactive factors, and loading parameters to regenerate both fibrous tissue and its interfaces. However, such a model system may prove valuable in identifying key parameters for next-generation tissue engineering approaches to recreating these complex structures.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian Nguyen (Georgia Tech BME undergraduate) for his help in collecting tensile degradation data. This research was supported by NIH R21EB008918 and an Arthritis Foundation Investigator Award to J.S.T.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Butler D.L. Dressler M. Awad H. Functional tissue engineering: assessment of function in tendon and ligament repair. In: Guilak F., editor; Butler D., editor; Goldstein S., editor; Mooney D., editor. Functional Tissue Engineering. New York: Springer; 2003. pp. 213–226. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mechanical properties of ligament and tendon. In: Martin R., editor; Burr D., editor; Sharkey N., editor. Skeletal Tissue Mechanics. New York, NY: Springer; 1998. pp. 309–346. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Louie L. Yannas I.V. Spector M. Tissue engineered tendon. In: Patrick C.W. Jr., editor; Mikos A.G., editor; McIntire L.V., editor. Frontiers in Tissue Engineering. New York: Elsevier Science Inc.; 1998. pp. 412–442. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler M.A. Behrend H. Henz S. Stutz G. Rukavina A. Kuster M.S. Function, osteoarthritis and activity after ACL-rupture: 11 years follow-up results of conservative versus reconstructive treatment. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16:442. doi: 10.1007/s00167-008-0498-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deng D. Liu W. Xu F. Yang Y. Zhou G. Zhang W.J. Cui L. Cao Y. Engineering human neo-tendon tissue in vitro with human dermal fibroblasts under static mechanical strain. Biomaterials. 2009;30:6724. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chokalingam K. Juncosa-Melvin N. Hunter S.A. Gooch C. Frede C. Florert J. Bradica G. Wenstrup R. Butler D.L. Tensile stimulation of murine stem cell-collagen sponge constructs increases collagen type I gene expression and linear stiffness. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:2561. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benhardt H.A. Cosgriff-Hernandez E.M. The role of mechanical loading in ligament tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2009;15:467. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEB.2008.0687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saber S. Zhang A.Y. Ki S.H. Lindsey D.P. Smith R.L. Riboh J. Pham H. Chang J. Flexor tendon tissue engineering: bioreactor cyclic strain increases construct strength. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:2085. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2010.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee I.C. Wang J.H. Lee Y.T. Young T.H. The differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells by mechanical stress or/and co-culture system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;352:147. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vunjak-Novakovic G. Altman G. Horan R. Kaplan D.L. Tissue engineering of ligaments. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2004;6:131. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.6.040803.140037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goshima J. Goldberg V.M. Caplan A.I. The osteogenic potential of culture-expanded rat marrow mesenchymal cells assayed in vivo in calcium phosphate ceramic blocks. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;262:298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caplan A.I. Review: Mesenchymal stem cells: cell-based reconstructive therapy in orthopedics. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:1198. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krych A.J. Jackson J.D. Hoskin T.L. Dahm D.L. A meta-analysis of patellar tendon autograft versus patellar tendon allograft in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:292. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Webb K. Hitchcock R.W. Smeal R.M. Li W. Gray S.D. Tresco P.A. Cyclic strain increases fibroblast proliferation, matrix accumulation, and elastic modulus of fibroblast-seeded polyurethane constructs. J Biomech. 2006;39:1136. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen J. Horan R.L. Bramono D. Moreau J.E. Wang Y. Geuss L.R. Collette A.L. Volloch V. Altman G.H. Monitoring mesenchymal stromal cell developmental stage to apply on-time mechanical stimulation for ligament tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:3085. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.3085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuo C.K. Tuan R.S. Mechanoactive tenogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14:1615. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2006.0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin H. Temenoff J.S. Mikos A.G. In vitro cytotoxicity of unsaturated oligo[poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate] macromers and their cross-linked hydrogels. Biomacromolecules. 2003;4:552. doi: 10.1021/bm020121m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shin H. Jo S. Mikos A.G. Modulation of marrow stromal osteoblast adhesion on biomimetic oligo[poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate] hydrogels modified with Arg-Gly-Asp peptides and a poly(ethyleneglycol) spacer. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;61:169. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Temenoff J.S. Athanasiou K.A. LeBaron R.G. Mikos A.G. Effect of poly(ethylene glycol) molecular weight on tensile and swelling properties of oligo(poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate) hydrogels for cartilage tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;59:429. doi: 10.1002/jbm.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altman G.H. Horan R.L. Martin I. Farhadi J. Stark P.R. Volloch V. Richmond J.C. Vunjak-Novakovic G. Kaplan D.L. Cell differentiation by mechanical stress. FASEB J. 2002;16:270. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0656fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cukierman E. Pankov R. Stevens D.R. Yamada K.M. Taking cell-matrix adhesions to the third dimension. Science. 2001;294:1708. doi: 10.1126/science.1064829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanderploeg E.J. Department of Mechanical Engineering. Georgia Institute of Technology; Atlanta, GA: 2006. Mechanotransduction in engineered cartilaginous tissues: in vitro oscillatory tensile loading [Ph.D. thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Temenoff J.S. Park H. Jabbari E. Conway D.E. Sheffield T.L. Ambrose C.G. Mikos A.G. Thermally cross-linked oligo(poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate) hydrogels support osteogenic differentiation of encapsulated marrow stromal cells in vitro. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5:5. doi: 10.1021/bm030067p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Connelly J.T. Mouw J.K. Vanderploeg E.J. Levenston M.E. Cyclic tensile loading influences differentiation of bovine bone marrow stromal cells in a TGF-beta dependent manner. Abstract presented at the Orthopaedic Research Society Meeting; Washington, DC. 2005. Abstract no. 0946. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Connelly J.T. Mouw J.K. Vanderploeg E.J. Levenston M.E. Cyclic tensile loading alters gene expression and matrix synthesis of bone marrow stromal cells. Abstract presented at the Orthopaedic Research Society Meeting; Chicago. 2006. Abstract no. 0999. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jo S. Shin H. Shung A. Fisher P. Mikos A.G. Synthesis and characterization of oligo(poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate) macromer. Macromolecules. 2001;34:2839. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Connelly J.T. Vanderploeg E.J. Mouw J.K. Wilson C. Levenston M.E. Tensile loading modulates BMSC differentiation and the development of engineered fibrocartilage constructs. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:1913. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Titushkin I. Cho M. Distinct membrane mechanical properties of human mesenchymal stem cells determined using laser optical tweezers. Biophys J. 2006;90:2582. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.073775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nieponice A. Maul T.M. Cumer J.M. Soletti L. Vorp D.A. Mechanical stimulation induces morphological and phenotypic changes in bone marrow-derived progenitor cells within a three-dimensional fibrin matrix. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;81:523. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McBeath R. Pirone D.M. Nelson C.M. Bhadriraju K. Chen C.S. Cell shape, cytoskeletal tension, and RhoA regulate stem cell lineage commitment. Dev Cell. 2004;6:483. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shin H. Quinten Ruhe P. Mikos A.G. Jansen J.A. In vivo bone and soft tissue response to injectable, biodegradable oligo(poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate) hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2003;24:3201. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Juncosa-Melvin N. Matlin K.S. Holdcraft R.W. Nirmalanandhan V.S. Butler D.L. Mechanical stimulation increases collagen type I and collagen type III gene expression of stem cell-collagen sponge constructs for patellar tendon repair. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:1219. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salinas C.N. Anseth K.S. The influence of the RGD peptide motif and its contextual presentation in PEG gels on human mesenchymal stem cell viability. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2008;2:296. doi: 10.1002/term.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghazanfari S. Tafazzoli-Shadpour M. Shokrgozar M.A. Effects of cyclic stretch on proliferation of mesenchymal stem cells and their differentiation to smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;388:601. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.08.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abousleiman R.I. Reyes Y. McFetridge P. Sikavitsas V. Tendon tissue engineering using cell-seeded umbilical veins cultured in a mechanical stimulator. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:787. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gong Z. Niklason L.E. Small-diameter human vessel wall engineered from bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) FASEB J. 2008;22:1635. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-087924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kearney E.M. Prendergast P.J. Campbell V.A. Mechanisms of strain-mediated mesenchymal stem cell apoptosis. J Biomech Eng. 2008;130:061004. doi: 10.1115/1.2979870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cruise G.M. Scharp D.S. Hubbell J.A. Characterization of permeability and network structure of interfacially photopolymerized poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate hydrogels. Biomaterials. 1998;19:1287. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bryant S.J. Anseth K.S. Hydrogel properties influence ECM production by chondrocytes photoencapsulated in poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;59:63. doi: 10.1002/jbm.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noth U. Schupp K. Heymer A. Kall S. Jakob F. Schutze N. Baumann B. Barthel T. Eulert J. Hendrich C. Anterior cruciate ligament constructs fabricated from human mesenchymal stem cells in a collagen type I hydrogel. Cytotherapy. 2005;7:447. doi: 10.1080/14653240500319093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kinneberg K.R. Nirmalanandhan V.S. Juncosa-Melvin N. Powell H.M. Boyce S.T. Shearn J.T. Butler D.L. Chondroitin-6-sulfate incorporation and mechanical stimulation increase MSC-collagen sponge construct stiffness. J Orthop Res. 2010;28:1092. doi: 10.1002/jor.21095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khatod M. Amiel D. Ligament biochemistry and physiology. In: Pedowitz R.A., editor; O'Connor J.J., editor; Akeson W.H., editor. Daniel's Knee Injuries. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2003. pp. 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jarvinen T.A. Jozsa L. Kannus P. Jarvinen T.L. Hurme T. Kvist M. Pelto-Huikko M. Kalimo H. Jarvinen M. Mechanical loading regulates the expression of tenascin-C in the myotendinous junction and tendon but does not induce de novo synthesis in the skeletal muscle. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:857. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharma P. Maffulli N. Biology of tendon injury: healing, modeling and remodeling. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2006;6:181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khatod M. Akeson W.H. Amiel D. Ligament injury and repair. In: Pedowitz R.A., editor; O'Connor J.J., editor; Akeson W.H., editor. Daniel's Knee Injuries. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2003. pp. 185–201. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mackie E.J. Ramsey S. Expression of tenascin in joint-associated tissues during development and postnatal growth. J Anat. 1996;188(Pt 1):157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bryant S.J. Anseth K.S. Controlling the spatial distribution of ECM components in degradable PEG hydrogels for tissue engineering cartilage. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;64:70. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]