Abstract

A critical barrier in tissue regeneration is scale-up. Bioengineered adipose tissue implants have been limited to ∼10 mm in diameter. Here, we devised a 40-mm hybrid implant with a cellular layer encapsulating an acellular core. Human adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) were seeded in alginate. Poly(ethylene)glycol-diacrylate (PEGDA) was photopolymerized into 40-mm-diameter dome-shaped gel. Alginate-ASC suspension was painted onto PEGDA surface. Cultivation of hybrid constructs ex vivo in adipogenic medium for 28 days showed no delamination. Upon 4-week in vivo implantation in athymic rats, hybrid implants well integrated with host subcutaneous tissue and could only be surgically separated. Vascularized adipose tissue regenerated in the thin, painted alginate layer only if ASC-derived adipogenic cells were delivered. Contrastingly, abundant fibrous tissue filled ASC-free alginate layer encapsulating the acellular PEGDA core in control implants. Human-specific peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) was detected in human ASC-seeded implants. Interestingly, rat-specific PPAR-γ was absent in either human ASC-seeded or ASC-free implants. Glycerol content in ASC-delivered implants was significantly greater than that in ASC-free implants. Remarkably, rat-specific platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM) was detected in both ASC-seeded and ASC-free implants, suggesting anastomosis of vasculature in bioengineered tissue with host blood vessels. Human nuclear staining revealed that a substantial number of adipocytes were of human origin, whereas endothelial cells of vascular wall were of chemaric human and nonhuman (rat host) origins. Together, hybrid implant appears to be a viable scale-up approach with volumetric retention attributable primarily to the acellular biomaterial core, and yet has a biologically viable cellular interface with the host. The present 40-mm soft tissue implant may serve as a biomaterial tissue expander for reconstruction of lumpectomy defects.

Introduction

Patients with breast cancer suffer from loss of breast tissue after either lumpectomy or mastectomy. Synthetic implants are one of the current choices for restoration of breast morphology. However, silicone gel or saline implants are associated with drawbacks such as capsular contracture, dislocation, potential leakage, extrusion, and ectopic mineralization.1,2 Substantial pain and/or tissue deformation may result from these adverse effects, necessitating secondary surgeries, including capsulotomy or capsulectomy.1,2 Alternatively, autologous tissue is surgically harvested for breast reconstruction including the transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap, and latissimus dorsi flap with or without alloplastic implants, deep inferior epigastric perforator flap, and superior gluteal perforator flap.3–5 Further, autologous preadipocyte transfer, without involvement of grafting, is utilized for soft tissue reconstruction or augmentation.6,7 However, autologous tissue grafting or autologous adipocyte transfer suffers from undesirable limitations, including donor-site morbidity, lack of donor tissue in certain patients, postsurgical volume reduction, and necrosis.6–9

A number of meritorious approaches have been attempted toward the bioengineering of soft tissue grafts that primarily consist of adipose tissue. Microencapsulated basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) in a minced collagen sponge scaffold (1 mL) induced subcutaneous adipogenesis.10 Human adipose stem cells seeded in placental decellularized matrix and cross-linked hyaluronan led to soft tissue formation subcutaneously in athymic mice.11 The presence of adipocytes with intracellular lipid accumulation and murine CD31 staining confirmed in vivo adipogenesis with vascularization.11 In vivo subcutaneous adipogenesis was induced from green fluorescent protein (GFP)-positive human adipose stem cells in a fibrin gel.12 Interestingly, the majority of cells in the fibrin gel after in vivo implantation derive from transplanted GFP-positive human adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs), rather than host mouse cells.12 Preadipocytes (3T3-L1) show enhanced adipogenic differentiation in enzymatically degradable poly(ethylene glycol)-based hydrogels that were modified with collagenase-sensitive peptides and cross-linked with branched poly(ethylene)glycol (PEG)-succinimidyl propionates or laminin-derived adhesion peptide,13 as a logical extension of previous studies.14,15 Similarly, RGD-modified polyethersulfone supported the adhesion of adipose stem cells.16 Human preadipocytes seeded in poly(L-lactic acid)-[PLLA]-reinforced polyglycolic acid (PGA) fibers yielded adipose tissue after in vivo implantation.17 Autologous sheep preadipocytes seeded in alginate hydrogel with or without RGD modification, after in vivo implantation, generated volumetrically maintained adipose tissue, with RGD-modified alginate showing advantage for cell adhesion and proliferation.18 Despite the above-mentioned progress in the area of adipose tissue engineering, several critical roadblocks remain, including interrelated issues of angiogenesis, scale-up, and the maintenance of anatomic shape and dimensions.19 Scale-up of bioengineered soft tissue grafts for the healing of lumpectomy or mastectomy defects is far from trivial, given unavoidable challenges of angiogenesis and cell survival. To date, the largest bioengineered adipose grafts have been typically 10 to 15 mm or less, including our previous work.20,21 The maintenance of volumetric shape and dimensions has only been realized in a small number of studies.17–21 Here, we devised a 40-mm novel hybrid implant consisting of a cellular alginate layer with human ASCs encapsulating an acellular core of PEG-diacrylate (PEGDA) photopolymerized into breast shape. After in vivo implantation, vascularized adipose tissue regenerated in ASC-seeded alginate layer with expression of human-specific peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) mRNA and rat-specific PECAM, demonstrating a viable approach for further scale-up of adipose tissue grafts as a biomaterial tissue expander for reconstruction of lumpectomy/mastectomy defects.

Materials and Methods

Isolation of human ASCs after lipectomy

After institutional review board (IRB) approval, adipose tissue was harvested from two anonymous human subjects undergoing body contouring procedures such as liposuction and abdominoplasty. ASCs were isolated from whole adipose tissue by mechanically mincing the tissue, followed by enzymatic digestion with collagenase II (1 mg/mL) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Sigma) for 30 min at 37°C (Fig. 1A). The tissue was then washed three times with DMEM to remove collagenase by sequential centrifugation (550 g for 10 min). After final wash, cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlanta Biologicals) and 1% antibiotic and antimycotic (10,000 U/mL penicillin [base], 10,000 μg/mL streptomycin, and 25 μg/mL amphotericin B; Atlanta Biologicals), homogenized, and plated at 37°C, 95% humidity, and 5% CO2. ASCs were culture-expanded for 4 weeks per our previous methods.22–24

FIG. 1.

Fabrication of hybrid soft tissue implant. (A) Human ASCs were culture expanded for 3 weeks. (B) PEGDA hydrogel was photopolymerized in breast shape (diameter 40 mm) without any cells. (C) ASCs were seeded in alginate solution and painted on PEDGA surface to form a hybrid construct. (D) After 4-week ex vitro cultivation, alginate-PEGDA hybrid construct showed no delamination, with or without ASCs. (E) After 4-week in vivo implantation, adipose tissue formed in ASC-seeded alginate later encapsulating an acellular PEGDA core. ASCs, adipose-derived stem cells; PEGDA, poly(ethylene)glycol-diacrylate. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

Fabrication and ex vivo cultivation of hybrid adipogenic implants

Hybrid adipogenic implants were fabricated by combining a PEGDA (MW 3400; Shearwater Polymers/Nektar AL) gel core in the shape of a breast mould and an external layer of cell-seeded alginate gel (Fig. 1B). PEGDA gel was fabricated per our previous methods.20,25 Briefly, PEGDA was dissolved in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with penicillin (100 U/mL) and streptomycin (100 μg/mL) to a final solution of 10% (w/v). A photoinitiator (0.05% w/v), 2-hydroxy-1-(4-[hydroxyethoxy]phenyl)-2-methyl-1-propanone (Ciba Specialty Chemicals), was added to the PEGDA solution. PEGDA/photoinitiator solution in PBS was pipetted into a preformed, dome-shaped mould and photopolymerized under long-wave UV light for 10 min to form the acellular core of the hybrid implant (Fig. 1B). A 4% (w/v) alginate solution was prepared by dissolving alginate (Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.85% NaCl solution. Culture-expanded ASCs (Fig. 1A) were trypsinized and seeded in 20 × 106 cell suspension in 1.5-mL medium (described above). A total of 1.5 mL of 4% (w/v) alginate solution was then added to the cell suspension and homogenized to form a 2% (w/v) alginate-ASC suspension. The alginate-ASC mixture was then pipetted onto the surface of the PEGDA gel core concurrently with 1.1% CaCl2 solution (10:1 ratio) for gelation to form a cell-seeded layer covering the acellular core of PEGDA gel. ASC-seeded hybrid implants were cultured overnight in DMEM/FBS and then transferred to adipogenic culture for 28 days consisting of an expansion medium supplemented with 1 μM dexamethasone, 60 μM indomethacin, 0.5 mM IBMX, and 10 μg/mL insulin (Fig. 1C). Acellular control hybrid implants were fabricated in the same manner, but without cells in alginate layer, and subjected to ex vivo cultivation in the same adipogenic medium for 28 days (Fig. 1D), followed by 4-week in vivo implantation (Fig. 1E).

In vivo implantation of hybrid constructs

After Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approval, athymic nude rats were anesthetized with isoflurane inhalation (3%) in an induction chamber with anesthesia maintained via a nose cone (1%–3% isoflurane). A 5.5-cm-long linear incision was made along the midsagittal line of the dorsum. One cell-seeded or control (cell-free) hybrid construct was implanted into a surgically created subcutaneous pocket in each rat (n = 6/group) (Fig. 2G). All implants were harvested after 4 weeks (Fig. 2H), and cut into two halves. One half was processed in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) for real-time (RT)-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or lysed in 1 × triton-X solution, minced, sonicated on ice for 20 s, and stored at −20°C until further analysis for glycerol content. The second half was fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin for histological and immunocytochemical analyses.

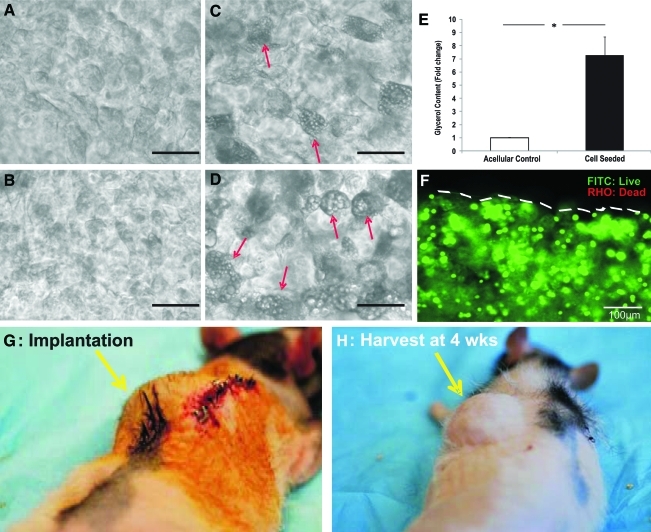

FIG. 2.

Ex vivo cultivation and in vivo implantation of hybrid implants. (A, B) Light microscopy of ASCs seeded in alginate gel layer encapsulating 40-mm PEGDA core, but without the adipogenic differentiation medium at 2 and 4 weeks showing no adipose lipid-bearing cells. (C, D) ASCs seeded in alginate gel layer encapsulating 40-mm PEGDA core in the adipogenic differentiation medium at 2 and 4 weeks showing intracellular lipid accumulation. Arrows indicate lipid vacuoles in adipocytes. (E) Glycerol content of ASC-seeded hybrid implants after 4-week ex vivo adipogenic differentiation in comparison with ASC-seeded hybrid implants without adipogenic differentiation. *p < 0.01. (F) Live/Dead (Live: green/FITC; Dead: red/rhodamine-RHO) viability assay of ASC-seeded hybrid implant after 4-week ex vivo adipogenic differentiation. Dashed line marking the external surface of alginate layer. Scale bar: 50 μm. (G) Implantation of breast-shaped hybrid implants subcutaneously in the dorsum of athymic rats. (H) Implant shape and dimensions were maintained after 4-week in vivo implantation. Arrows in G and H indicate adipogenic graft at the time of implantation and retrieval, respectively. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

Histology, RT-PCR, immunocytochemistry, and glycerol content

Specimens were sequentially sectioned in the transverse plane at 5-μm thickness and stained with hematoxylin and eosin or Masson's Trichrome. For RT-PCR, total RNA was isolated using Trizol per manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 100 mg of in vivo harvested tissue was homogenized in 1 mL Trizol. The samples were centrifuged. RNA in water phase was precipitated by isopropanol. After washing with 70% ethanol, total RNA was dissolved in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC) water. cDNA was synthesized using 1-μg RNA by iscript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-rad). Expression of target genes was determined by the following gene-specific primers—human PPAR-γ: forward 5′-TGTCAGTACTGTCGGTTTCAG-3′, reverse CTGGAGA TCTCCGCCAACAG-3′; rat PPAR-γ: forward 5′-TCTCCA GCATTTCTGCTCCACACT-3′, reverse 5′-TGGTCAGCGG GAAGGACTTTATGT-3′; rat PECAM-1: forward 5′-TTGCC TCAGTCTGCAGGAGTCTTT-3′, reverse TGTACACCAGC GCATCGTCCTTAT-3′; rat GAPDH: forward 5′-TGACTCT ACCCACGGCAAGTTCAA-3′, reverse 5′-TCTCGTGGTTCA CACCCATCACAA-3′. All biochemical assays were evaluated using thawed, lysed samples. Glycerol content was detected by processing the lysate with triglyceride reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) followed by reaction with free glycerol reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) per manufacturer's protocol and read with a microplate reader at 540 nm (n = 4/group). Human cell nuclear staining (HuNu) was performed by incubating with an antibody (MAB1281; Millipore) per our prior methods.26 Viability of ASC-derived adipogenic cells after 4-week ex vivo adipogenic differentiation but before in vivo implantation was evaluated using a Live/Dead assay per manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen).

Statistical analysis

Upon confirmation of normal data distribution, Student's t-tests were used at α level of 0.05.

Results

Adipogenesis of ASC-seeded hybrid constructs ex vivo

Human ASCs encapsulated in three-dimensional (3D) alginate gel and exposed to the adipogenic differentiation medium acquired marked lipid vacuoles under light microscopy by 2 weeks (Fig. 2C), compared with absence of adipogenesis in the acellular 3D alginate gel that was also subjected to adipogenic differentiation (Fig. 2A). Adipogenesis of human ASCs in 3D alginate gel became increasingly pronounced by 4 weeks (Fig. 2D), as opposed to no adipogenesis in cell-free alginate gel (Fig. 2B). Glycerol content of human ASC-seeded constructs was sevenfold greater upon 4-week cultivation in the adipogenic differentiation medium than control acellular constructs (Fig. 2E). Live/Dead assay showed overwhelming viability of seeded human ASCs in alginate gel after 4-week ex vivo adipogenic differentiation (Fig. 2F). No delamination was observed between alginate and PEGDA layers.

Scale-up of in vivo harvested hybrid adipose tissue implants

Hybrid implants retrieved from in vivo subcutaneous tissue maintained the original shape and overall dimensions after 4-week implantation (Fig. 2H as compared with Fig. 2G). Upon surgical opening of the implant site, the representative cell-seeded hybrid implants well adhered to the surrounding host tissue (Fig. 3A) with marked adipose tissue in its periphery (Fig. 3A, C, arrows), whereas the representative acellular hybrid implants had little indication of adipose tissue formation (Fig. 3D, E, arrows in E). Remarkably, the representative cell-seeded hybrid implant showed marked vascularization upon gross examination (Fig. 3B, C, arrow head). Contrastingly, the representative acellular control implants showed little sign of vascularization (Fig. 3F).

FIG. 3.

Harvested hybrid soft tissue grafts after 4-week in vivo implantation. (A, B) Hybrid implants with ASC-seeded in external alginate layer showing adipose tissue integration with surrounding host tissues (arrows). Angiogenesis (arrow heads) is present in ASC-seeded alginate layer of the hybrid implant. (C) Cross section of the hybrid implant showing apparent soft tissue over a filler core (arrows). (D, E) Control, cell-free hybrid implant showing absence of adipose tissue surrounding filler core. (F) Cross section of control hybrid implant showing absence of tissue coat. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

Histology, RT-PCR, and glycerol content of hybrid implants

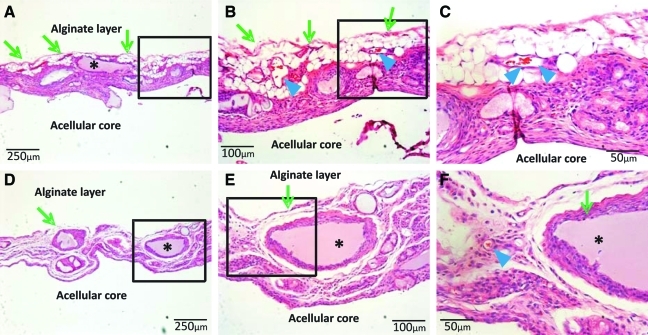

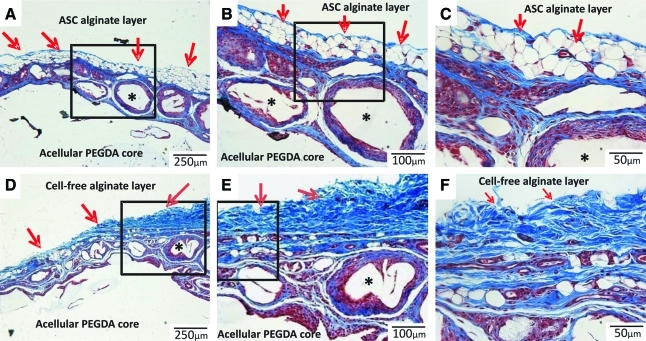

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the cell-seeded alginate layer of the representative hybrid implants showed widespread adipose tissue that encapsulated the acellular core of PEGDA hydrogel (Fig. 4A, arrows). Higher magnification revealed erythrocyte-filled blood vessels within adipose tissue (Fig. 4B, C, arrow heads). There were islands of apparently remaining alginate gel that was surrounded by cells (Fig. 4A, asterisks). Contrastingly, acellular hybrid implants showed infiltration of apparently host fibrous cells, which populated residual alginate gel encapsulating the acellular PEGDA, but a lack of host-initiated adipogenesis (Fig. 4D–F). There were islands of apparently remaining alginate gel that were surrounded by the infiltrated host fibroblast-like cells (Fig. 4D–F, asterisks). Masson's Trichrome staining revealed a thin layer of fibrous tissue at the interface of the bioengineered adipose tissue with host skin (removed during surgical retrieval) (Fig 5A–C, arrows) and with the underlying acellular PEGDA core (Fig 5A–C). Strikingly, there was little fibrous tissue present in the bioengineered adipose tissue (Fig 5A–C). In contrast, substantial fibrous tissue was present surrounding the acellular PEGDA core of the representative acellular implant (Fig. 5D–F). Because no exogenous cells were seeded in the acellular scaffolds, all fibroblast-like cells must have been host derived (Fig. 5D–F).

FIG. 4.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of in vivo harvested hybrid implants. (A–C) ASC-seeded hybrid implants; (D–F) ASC-free hybrid implants. (A) Adipogenic tissue coat surrounding the acellular core of the hybrid implant in low magnification. Asterisk indicates residue alginate. (B) Higher magnification of box in (A) showing abundant adipocytes (arrows) with blood vessels (arrowheads). (C) Higher magnification of box in (B) showing erythrocyte containing blood vessels lining with endothelial cells (arrowheads). (D) Control, cell-free hybrid implants showing absence of adipose tissue and acellular PEGDA core. Asterisk indicates residue alginate. (E) Fibrous tissue formation was present in the alginate layer without any seeded ASCs. (F) Fibroblast-like cells populated alginate layer with some blood vessels (arrowhead). Asterisk indicates residue alginate. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

FIG. 5.

Masson's trichrome staining of in vivo harvested hybrid implants. (A–C) ASC-seeded alginate layer showing abundant adipocytes with minimal surrounding fibrous tissue. Fibrous tissue surrounds residue alginate particles (*) and over the surface of acellular PEGDA hydrogel. (D–F) Abundant fibrous tissue was present in the alginate layer of control hybrid implants (arrows), with residue alginate particles (*), encapsulating the acellular PEGDA hydrogel core. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

To characterize the origin of the bioengineered adipose tissue in hybrid implants, human- and rat-specific PPAR-γ, a key adipogenesis transcriptional factor, was detected by real-time PCR. Human PPAR-γ was detected in all cell-seeded hybrid implants with a concomitant lack of rat PPAR-γ (n = 6/group) (Fig. 6A), indicating that bioengineered adipose tissue was derived primarily from the transplanted human ASCs. In contrast, no human-specific PPAR-γ was detected in the acellular hybrid implant, which is consistent with histological data. There was no detectable rat-derived PPAR-γ in any of the samples (n = 6/group) (Fig. 6A), indicating minimal contribution to bioengineered adipogenesis by host cells in the current biomaterial configuration. Rat-specific PECAM was detected in either acellular or cell-seeded samples (n = 6/group) (Fig. 6A). Despite multiple attempts, human PECAM primer failed. Nonetheless, expression of rat-specific PECAM and angiogenesis in cell-seeded samples (n = 6/group) (Fig. 6B, C) suggests that angiogenesis in bioengineered adipose tissue, which presumably demands rich vascular supply and oxygen, anastomized with host blood vessels. Qualitatively, rat PECAM is not as pronounced in the acellular control group as in the ASC-seeded group (n = 6/group) (Fig. 6A). Glycerol content of ASC-seeded hybrid implants was significantly greater than that of ASC-free specimens (n = 6/group) (p < 0.05; n = 4) (Fig. 6B). Human cell nuclear staining revealed little positive staining in a representative control scaffold without any human cells (Fig. 6C), indicating that cells in the alginate layer of the scaffold were primarily host (rat) derived. Contrastingly, substantial numbers of adipocytes were positive to human nuclear staining (red arrows in Fig. 6D) and therefore are of human origin, whereas endothelial cells were chemaric with both human and nonhuman (rat) origins (green arrows indicating positive human cell nuclear staining in Fig. 6D).

FIG. 6.

Characterization of in vivo harvested hybrid implants. (A) Real-time (RT)-polymerase chain reaction for human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ), rat PPAR-γ, and rat platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM) of control hybrid implants and cell-seeded adipogenic hybrid implants. Human PPAR-γ was expressed in human adipose stem cell (ASC)-seeded hybrid implants. Rat PPAR-γ was not detected in human ASC-seeded hybrid implants, indicating that bioengineered adipose tissue was derived primarily from transplanted human ASCs. Rat-specific PECAM was detected in both acellular and cell-seeded samples, suggesting anastomosis of blood vessels in bioengineered adipose tissue with host vasculature. (B) Glycerol content of ASC-seeded hybrid implants was significantly greater than cell-free specimens (*p < 0.05; n = 4). (C) Human nuclear staining revealed few positive cells, suggesting that cells in alginate layer of the control group without human cell transplantation are host derived. (D) Positive human nuclear staining of the majority of adipogenic cells (red arrows) suggests human origin of transplanted cells, whereas mixed endothelial cell staining (green arrows) reveals a chimera of host and transplanted endothelial cells, indicating anastomosis of blood vessels in bioengineered adipose tissue with host vasculature. Scale bar: 100 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

Discussion

The present findings provide a glimpse of an integrated interface between host subcutaneous soft tissue and bioengineered adipose tissue encapsulating a sizable tissue expander. The bioengineered soft tissue implant with a diameter of ∼40 mm is sufficient for reconstruction of many facial soft tissue defects and some lumpectomy defects. Given the thinness of the bioengineered interface (a few hundred microns), survival of adipogenic cells in bioengineered soft tissue implant is excellent. Angiogenesis in bioengineered adipose tissue is observed in the present study, similar to vascularization in microchannel conduits in our previous work.21 Scale-up of bioengineered soft tissue implants up to ∼40 mm in diameter is enabled by a thin layer of ASC-derived, vascularized adipose tissue that not only integrates with host subcutaneous tissue, but also encapsulates a volume expander of acellular, biocompatible hydrogel, leading to an overall 40-mm diameter. In comparison to other scale-up approaches such as microchannel conduits as in our previous work,21 the present study takes a different direction to enlarge tissue-engineered implants by an acellular core. Adipose tissue presents a multitude of challenges for tissue engineering, partially because adipose tissue consists of abundant adipocytes with little extracellular matrix. However, ex vivo cell expansion is necessarily associated with increasing cost. This dichotomy is addressed in the present study to seed minimally expanded ASCs in a thin alginate layer, whereas scale-up relies on the large acellular PEGDA core. Had we attempted to seed ASCs in all of the 40-mm constructs, substantial cell expansion would have been required in a model that is challenging for clinical translation. The present approach yields a substantial increase in the size of bioengineered adipose implants at the expense of an acellular biomaterial core rather than excessive ex vivo cell cultivation. Previously, we have shown maintenance of the dimensions of bioengineered adipose tissue up to ∼10 mm in diameter.20,21 In the present work, dimensional comparison of cell-seeded and cell-free implants is not valid because the present scale-up derives primarily by the acellular core of biomaterials. The thin adipogenic layer (up to a few hundred microns) in the present work is virtually impossible to measure, because bioengineered adipose tissue integrates with host subcutaneous tissue and cannot be surgically separated. Given the thinness of the engineered adipose tissue, there was little appreciable change in the overall volume of the construct in the range of ∼40 mm by the acellular core. Accordingly, the present work explores a new direction for scale-up, yielding a 40-mm diameter soft tissue implant that is similar in size to multiple facial soft tissue defects or lumpectomy defects.

Survival of regenerated adipose tissue depends critically on vascular supply.19,27,28 Likely attributable to a design of adipogenesis in a thin layer in alginate, transplanted ASCs have survived after 4-week ex vivo cultivation, as verified by Live/Dead assay. In vivo adipogenesis with closely packed adipocytes in alginate mimics native adipose tissue and indicates that the transplanted ASCs, after 4-week ex vivo adipogenic differentiation, are capable of regenerating adipose tissue subcutaneously in the host. Expression of human-specific PPAR-γ and concomitant absence of rat-specific PPAR-γ suggest that bioengineered adipose tissue derives primarily from transplanted human ASCs. This finding is consistent with previous reports that bioengineered adipose tissue in mice is contributed primarily by transplanted, GFP-positive human ASCs in fibrin gel, rather than host mouse cells.12 Previous work has also shown that subcutaneous injection of adipogenic cues such as bFGF, without cell transplantation, elaborates small adipose tissue formation.10,29 Whereas host endogenous cells upon adipogenic stimulation and transplanted adipogenic cells are both capable of elaborating adipose tissue, there appears to be a difference in the scale of the bioengineered adipose tissue. Previously, bFGF-elaborated adipose tissue pads are small (typically <10 mm in diameter).10,17 As a scale-up, sheep preadipocytes in alginate hydrogel yielded volumetrically maintained adipose tissue with a diameter of ∼15 mm after in vivo implantation.18 In the present work, transplanted human ASCs are capable of generating a 40-mm hybrid soft tissue graft with cell survival in a thin layer of cellular interface with the host, and with volumetric expansion attributable to a large acellular biomaterial core. Whereas small adipose tissue can be regenerated by injectable cytokines in a biomaterial, clinical needs for adipose tissue regeneration are frequently sizable facial defects or lumpectomy/mastectomy defects resulting from breast cancer. Remarkably, rat-specific PECAM is identified in bioengineered adipose tissue, suggesting that blood vessels in bioengineered adipose tissue have anastomized with host vasculature.11,22 Human nuclear staining indicates that bioengineered adipose tissue derives primarily from transplanted human ASCs, whereas endothelial cells of blood-vessel-like structures in bioengineered adipose tissue are both transplanted (human) and host (rat) origins.

In vivo adipogenesis by adipose stem cells seeded in biomaterials, once committed toward adipogenic lineage, is also a function of degradation of the biomaterials in long term. Interestingly, we found a lack of delamination after 4-week ex vivo culture of hybrid constructs with an external alginate layer encapsulating an acellular PEGDA gel core, with or without ASC seeding in alginate. Viability of encapsulated cells after 4-week ex vivo adipogenic differentiation indicates the integrity of hybrid construct and cytocompatibility of alginate gel. From the amount of adipogenesis after 4-week in vivo implantation, it appears that some alginate has undergone degradation. Additional work is warranted to synchronize the rates of in vivo adipogenesis and alginate degradation, especially in long-term studies and in preclinical models. In the present work, fibrous tissue predominates in the alginate layer of control hybrid implants (without any ASCs), which is confirmed by the paucity of either human- or rat-specific PPAR-γ. Interestingly, adipose tissue dominates in the interface with native host tissue in ASC-seeded scaffolds, with some fibrous tissue between bioengineered adipose tissue and the acellular PEGDA gel. One of the additional challenges of the present work is to appreciate cell composition after degradation of acellular material core, which we plan to investigate in preclinical models. Luckily, previous work has paved ways for increasingly translational applications of adipogenic cells in preclinical models or even patients, for example, with serum-free culture to avoid the use of FBS.30 Nonetheless, the present findings provide a previously untested approach for scale-up of bioengineered tissue grafts, potentially useful for the reconstruction of soft tissue defects resulting from trauma, chronic diseases, congenital anomalies, aging, or tumor resection.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Kennedy and F. Guo for technical and administrative support. The work ws supported by a grant from Women at Risk (WAR) to E.K.M. and NIH Grant R01EB006263 to J.J.M.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Shiffman M.A. Silicone breast implant litigation (Part 1) Med Law. 1994;13:681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jenkins M.E. Friedman H.I. von Recum A.F. Breast implants: facts, controversy, and speculations for future research. J Invest Surg. 1996;9:1. doi: 10.3109/08941939609012455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Z.D. Heymans O. Breast implants. A review. Acta Chir Belg. 2004;104:158. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2004.11679528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnez Z.M. Khan U. Pogorelec D. Planinsek F. Breast reconstruction using the free superficial inferior epigastric artery (SIEA) flap. Br J Plast Surg. 1999;52:276. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1999.3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnez Z.M. Khan U. Pogorelec D. Planinsek F. Rational selection of flaps from the abdomen in breast reconstruction to reduce donor site morbidity. Br J Plast Surg. 1999;52:351. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1999.3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niechajev I. Sevcuk O. Long-term results of fat transplantation: clinical and histologic studies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;94:496. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199409000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsudo P.K. Toledo L.S. Experience of injected fat grafting. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1988;12:35. doi: 10.1007/BF01570383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de la F.A. Tavora T. Fat injections for the correction of facial lipodystrophies: a preliminary report. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1988;12:39. doi: 10.1007/BF01570384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chajchir A. Benzaquen I. Liposuction fat grafts in face wrinkles and hemifacial atrophy. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1986;10:115. doi: 10.1007/BF01575279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimura Y. Tsuji W. Yamashiro H. Toi M. Inamoto T. Tabata Y.J. In situ adipogenesis in fat tissue augmented by collagen scaffold with gelatin microspheres containing basic fibroblast growth factor. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2010;4:55. doi: 10.1002/term.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flynn L. Prestwich G.D. Semple J.L. Woodhouse K.A. Adipose tissue engineering in vivo with adipose-derived stem cells on naturally derived scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;89:929. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mizuno H. Itoi Y. Kawahara S. Ogawa R. Akaishi S. Hyakusoku H. In vivo adipose tissue regeneration by adipose-derived stromal cells isolated from GFP transgenic mice. Cells Tissues Organs. 2008;187:177. doi: 10.1159/000110805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brandl F. Hammer N. Blunk T. Tessmar J. Goepferich A. Biodegradable hydrogels for time-controlled release of tethered peptides or proteins. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:496. doi: 10.1021/bm901235g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischbach C. Spruss T. Weiser B. Neubauer M. Becker C. Hacker M. Göpferich A. Blunk T. Generation of mature fat pads in vitro and in vivo utilizing 3-D long-term culture of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Exp Cell Res. 2004;300:54. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiser B. Prantl L. Schubert T.E. Zellner J. Fischbach-Teschl C. Spruss T. Seitz A.K. Tessmar J. Goepferich A. Blunk T. In vivo development and long-term survival of engineered adipose tissue depend on in vitro precultivation strategy. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14:275. doi: 10.1089/tea.2007.0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin Y.C. Brayfield C.A. Gerlach J.C. Rubin J.P. Marra K.G. Peptide modification of polyethersulfone surfaces to improve adipose-derived stem cell adhesion. Acta Biomater. 2009;5:1416. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho S.W. Song K.W. Rhie J.W. Park M.H. Choi C.Y. Kim B.S. Engineered adipose tissue formation enhanced by basic fibroblast growth factor and a mechanically stable environment. Cell Transplant. 2007;16:421. doi: 10.3727/000000007783464795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halberstadt C. Austin C. Rowley J. Culberson C. Loebsack A. Wyatt S. Coleman S. Blacksten L. Burg K. Mooney D. Holder W., Jr. A hydrogel material for plastic and reconstructive applications injected into the subcutaneous space of a sheep. Tissue Eng. 2002;8:309. doi: 10.1089/107632702753725067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stosich M.S. Moioli E.K. Wu J.K. Lee C.H. Rohde C. Yousef A.M. Ascherman J. Diraddo R. Marion N.W. Mao J.J. Bioengineering strategies to generate vascularized soft tissue grafts with sustained shape. Methods. 2009;47:116. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alhadlaq A. Tang M. Mao J.J. Engineered adipose tissue from human mesenchymal stem cells maintains predefined shape and dimension: implications in soft tissue augmentation and reconstruction. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:556. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stosich M.S. Bastian B. Marion N.W. Clark P.A. Reilly G. Mao J.J. Vascularized adipose tissue grafts from human mesenchymal stem cells with bioactive cues and microchannel conduits. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:2881. doi: 10.1089/ten.2007.0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moioli E.K. Clark P.A. Chen M. Dennis J.E. Erickson H.P. Gerson S.L. Mao J.J. Synergistic actions of hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells in vascularizing bioengineered tissues. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:3922. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moioli E.K. Clark P.A. Sumner D.R. Mao J.J. Autologous stem cell regeneration in craniosynostosis. Bone. 2008;42:332. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moioli E.K. Hong L. Mao J.J. Inhibition of osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15:413. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alhadlaq A. Mao J.J. Tissue-engineered neogenesis of human-shaped mandibular condyle from rat mesenchymal stem cells. J Dent Res. 2003;82:951. doi: 10.1177/154405910308201203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang R. Chen M. Lee C.H. Yoon R. Lal S. Mao J.J. Clones of ectopic stem cells colonize muscle defects in vivo. PLoS ONE. 2010 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013547. (In press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patrick C.W. Breast tissue engineering. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2004;6:109. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.6.040803.140032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christiaens V. Lijnen H.R. Angiogenesis and development of adipose tissue. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;318:2. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hebert T.L. Wu X. Yu G. Goh B.C. Halvorsen Y.D. Wang Z. Moro C. Gimble J.M. Culture effects of epidermal growth factor (EGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) on cryopreserved human adipose-derived stromal/stem cell proliferation and adipogenesis. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2009;3:553. doi: 10.1002/term.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boone C. Grégoire F. Remacle C. Culture of porcine stromal-vascular cells in serum-free medium: differential action of various hormonal agents on adipose conversion. J Anim Sci. 2000;78:885. doi: 10.2527/2000.784885x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]