Abstract

Interleukin-12 (IL-12)-mediated immune responses are critical for the control of malignant development. Tumors can actively resist detrimental immunity of the host via many routes. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is one of the major immune-suppressive factors derived from many types of tumors. Here, we show that systemic administration of recombinant IL-12 could therapeutically control the growth of aggressive TS/A and 4T1 mouse mammary carcinomas. However, PGE2 produced by tumors potently inhibits the production of endogenous IL-12 at the level of protein secretion, mRNA synthesis, and transcription of the constituent p40 and p35 genes. The inhibition can be reversed by NS-398, a selective inhibitor of the enzymatic activity of cyclooxygenase 2 in PGE2 synthesis. Moreover, PGE2-mediated inhibition of IL-12 production requires the functional cooperation of AP-1 and AP-1 strongly suppresses IL-12 p40 transcription. Blocking PGE2 production in vivo results in a marked reduction in lung metastasis of 4T1 tumors, accompanied by enhanced ability of peritoneal macrophages to produce IL-12 and spleen lymphocytes to produce interferon-γ. This study contributes to the elucidation of the molecular mechanisms underlying the interaction between a progressive malignancy and the immune defense apparatus.

Keywords: activated protein-1, cytotoxic T lymphocyte, natural killer cells, macrophage, tumor immunity

Introduction

Interleukin-12 (IL-12) is a heterodimer produced primarily by macrophages and dendritic cells (DC) in innate and adaptive immune responses. It is a key factor in the induction of T cell-dependent and -independent activation of macrophages and natural killer (NK) cells, generation of T helper type 1 (Th1) cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL), induction of opsonizing, complement-fixing antibodies, and resistance to intracellular infections [1]. IL-12 has in recent years emerged as a promising cytokine able to dramatically activate the host's immune defense against a variety of tumors in animal models [2]. The ability of IL-12 to stimulate five important branches of immune effector cells (NK, CTL, Th, DC, and macrophages) leaves tumors little chance to escape. Indeed, recent encouraging developments in clinical applications of IL-12 for human T cell lymphoma [3, 4], B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma [5], melanoma [6–10], and renal carcinoma [11] strongly highlight the potential of IL-12 and its related molecules as rational candidates for anti-tumor therapies.

Tumors, however, often evade immune activation by producing immunosuppressive agents such as IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), which seriously dampen immune activation [12]. Indeed, dysregulation of IL-12 occurs between mouse mammary tumor-proximal [13, 14] and distal [15] immune cell populations.

Prostaglandins (PGs) are multipotential mediators in many biological responses. Numerous studies have demonstrated that PGs are important regulators of macrophages [16–20]. PGs produced by tumor cells or tumor-associated host cells (macrophages, endothelial cells, and stromal cells) have long been considered to play a stimulating role in the progression and metastasis of a variety of animal and human tumors [21–24]. The production and release of PGE2 by tumors, in particular, have been associated with general suppression of immune responses. It has also been demonstrated directly in a variety of systems to be a potent inhibitor of IL-12 production by macrophages and DC [13, 25–32]. PGE2 signal transduction is mediated through seven transmembrane prostanoid receptors, primarily EP2 and EP4. It involves G proteins coupled to these receptors and leads to induction of intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) accumulation [33, 34]. The inhibitory effects of PGE2 on IL-12 production are a result of its cAMP-inducing activity, as they could be mimicked by other cAMP inducers and are independent of IL-10, as neutralizing anti-IL-10 antibodies are unable to reverse this inhibition [25].

TS/A is an aggressive and poorly immunogenic cell line established from a moderately differentiated mammary adenocarcinoma that arose spontaneously in a multiparous BALB/c mouse [35]. It grows progressively, kills nu/nu and syngeneic mice, and gives rise to lung metastases. It expresses major histocompatibility complex class I (H-2Dd, H-2Kd) but not class II molecules, secretes granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (CSF), granulocyte macrophage-CSF, TGF-β, basic fibroblast growth factor, and vascular endothelial growth factor, and does not stimulate a syngeneic antitumor response in vivo nor in mixed lymphocyte-tumor cell cultures [36]. IL-12 administered to TS/A tumor-bearing mice via various routes at different stages of tumor establishment has been shown to cause the rejection of the tumor in wild-type BALB/c mice through a CD8+ T-lymphocyte-dependent reaction associated with macrophage infiltration, vessel damage, and necrosis. A certain degree of tumor immune memory is also established following IL-12 treatment [37, 38].

4T1 is a tumor cell line isolated from a single, spontaneously arising mammary tumor from a BALB/BfC3H mouse (mouse mammary tumor virus+; [39]). The 4T1 tumor closely mimics human breast cancer in its anatomical site, immunogenicity, growth characteristics, and metastatic properties [40]. From the mammary gland, 4T1 tumor spontaneously metastasizes to a variety of target organs including the lung, bone, brain, and liver through primarily a hematogenous route [41]. IL-12 administration to 4T1 tumor-bearing mice causes a substantial reduction in spontaneous metastases in the lungs and significantly prolongs their survival time [42].

These properties make TS/A and 4T1 mammary tumor models excellent systems in which to investigate the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in IL-12 production and IL-12-mediated control of the malignant development. In the present study, we asked two fundamental questions: How does tumor-derived PGE2 inhibit IL-12 production by macrophages? What are the effects of reversing the inhibition of IL-12 expression in mice bearing these mammary tumors?

Materials and Methods

Mice

Female BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks old) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All mice were housed at the Weill Medical College of Cornell University Animal Facilities (New York, NY) in accordance with the Principles of Animal Care (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1985). Mice bearing TS/A or 4T1 tumors were all killed no later than Day 28 as a result of the morbidity caused by large tumor sizes and extensive metastases.

Reagents

All antibodies used for supershift were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (Santa Cruz, CA). PGE2 and NS-398 were purchased from Caymen Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI).

Plasmids

Dr. Stephen Smale (University of California, Los Angeles) provided the mouse IL-12 p40 reporter construct spanning between −356 and +56 [43]. We [44] generated the human tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) promoter construct. Dr. Thomas Curren (St. Jude Children's Hospital, Memphis, TN) and A-Fos, by Dr. Charles Vinson (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD) provided expression vectors for c-Fos and c-Jun. All plasmids were prepared using the endotoxin-free maxi kit from Qiagen (Valencia, CA).

Tumor implantation, size measurement, lung metastasis assay

TS/A mammary carcinoma cells (1 × 105) were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) into the flank of recipient mice. 4T1 tumor cells (1 × 105) were injected s.c. into the abdominal mammary gland area of mice in 0.1 ml of a single-cell suspension in phosphate-buffered saline on Day 0. The dose of tumor implantation was empirically determined to give rise to tumors of ∼10 mm in diameter in untreated wild-type mice in 21–23 days. Primary tumors were measured using electronic calipers every 2–3 days. Tumor size was the square root of the product of two perpendicular diameters. Numbers of metastatic 4T1 cells in lung were determined by the clonogenic assay [40].

IL-12 and NS-398 treatment

Recombinant murine (rm)IL-12 was provided by Genetics Institute (Cambridge, MA). IL-12 treatment was given by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection at 500 ng (TS/A) four times a week in consecutive days with a 3-day rest or 1 μg (4T1) per mouse every other day, starting on Day 7 until the end of each experiment, unless otherwise described. This regiment of IL-12 was well tolerated with no signs of overt toxicity. NS-398 was given i.p. at 10 mg/kg five times a week in five consecutive days with a 2-day rest. This dosing and scheduling were adapted from a similar study by Stolina et al. [30].

Cells

The murine macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Inflammatory peritoneal exudate macrophages were obtained by lavage 3 days after injection of sterile, 3% thioglycolate broth (2 ml i.p.). Cells were washed and resuspended in RPMI containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and standard supplements. Macrophages were plated in 48-well tissue-culture dishes (0.5 × 106 cells/well). After 2 h incubation to allow for adherence of macrophages, monolayers were washed three times to remove nonadherent cells and were incubated with RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FCS and standard supplements. For stimulation, cells were treated the next day with lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 1 μg/ml), or murine interferon-γ (mIFN-γ; 10 ng/ml), first for 16 h (priming), followed by LPS.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA)

Supernatants from cultured cells were harvested 24 h after appropriate stimulation. mIL-12 p40, p70, and IL-10 were detected by ELISA (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PGE2 was assayed by an enzyme immunoassay kit from Cayman Chemicals. Mouse TGF-β1 was measured by ELISA with a rat anti-mouse monoclonal capture antibody (A75-2.1) from BD PharMingen.

RNase protection assay (RPA)

Mouse macrophages were pretreated with or without IFN-γ for 16 h followed by treatment with LPS for an additional 4 h. Total RNA (10 μg) of each sample was subjected to analysis by the multiprobe RNase protection kit mCK2b (BD PharMingen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Transient transfection

Transient transfections were performed by electroporation as described previously [45]. For cotransfections with effector expression vectors, the total amount of expression vectors was kept constant. Each cotransfection was done with a constant amount of a mixture of the effector vector (c-Fos or c-Jun) and control vector [cytomegalovirus (CMV)500 ]. The only variation is the ratio of the effector vector and control vector in the mix in each transfection. Transfection efficiency was routinely monitored by β-galactosidase (β-gal) assay by cotransfection with 3 μg pCMV-β-gal plasmid. Variability in β-gal activity between samples was typically within 5%. Lysates were used for luciferase and β-gal assays.

Nuclear extract preparation

Nuclear extracts were prepared according to the method of Schreiber et al. [46].

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

EMSA and supershift were performed as described previously [47]. The activated protein-1 (AP-1) oligonucleotide used was CGCTTGATGACTCAGCCGGGA; the underlined sequence denotes the consensus-binding site.

Statistical tests

Tumor growth and metastasis data to be compared were first subjected to normality test (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). When the samples studied were normally distributed, statistical comparisons were performed using the Student's t-test. Where the samples deviated from normality, a nonparametric, Mann-Whitney Rank-Sum test was used for comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaStat software. For all experiments, the mean and sd or sem are depicted.

Results

rIL-12 can control growth of mammary tumors

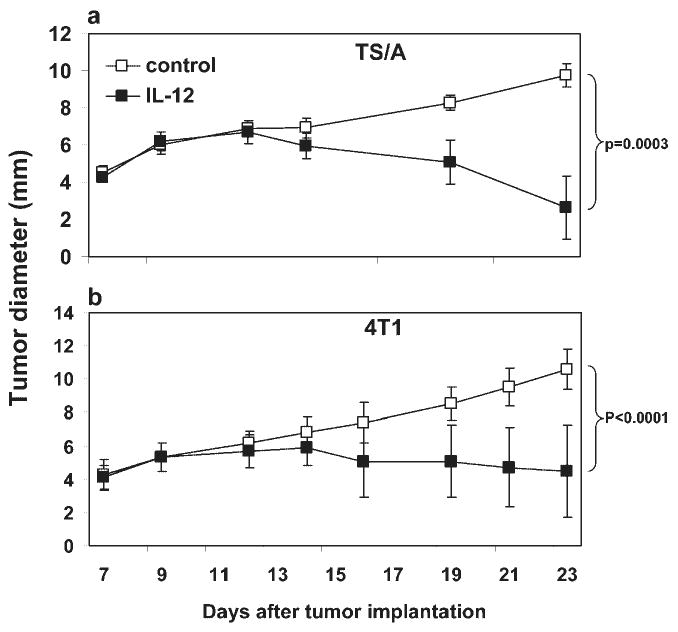

To assess the efficacy of therapeutic application of IL-12 in the TS/A and 4T1 murine mammary carcinoma models, we administered mouse rIL-12 to BALB/c mice carrying these tumors initiated by s.c. injection of the respective tumor cells. On Day 7 when the tumors averaged in size 4–5 mm in diameter, IL-12 was given on schemes as described in Materials and Methods until Day 23 when the mice were killed. As shown in Figure 1, IL-12 was able to restrain the growth of TS/A (Fig. 1a) and 4T1 (Fig. 1b) tumors with a statistically greater efficacy in the former model. These results confirm published data about the anti-tumor activities of IL-12 observed in these models and suggest that IL-12 is capable of countering the aggressive immune suppression in these poorly immunogenic mammary tumors.

Fig. 1.

Effects of IL-12 on TS/A and 4T1 tumor growth and metastasis in syngeneic mice. TS/A (a) and 4T1 (b) mammary carcinoma cells were injected s.c. in the abdominal mammary gland. Tumor growth was monitored every 2–3 days, and tumor size in diameter (mm) was measured with an electronic caliper. Each data point is comprised of five mice (TS/A) and 10 mice (4T1), respectively. Error bars represent standard deviation. IL-12 treatment started on Day 7 and was injected i.p. four times a week at 500 ng (a) or 1 μg (b) per mouse. The differences in tumor size between control and IL-12-treated groups on Day 23 are highly significant, based on Student's t-test. Data shown represent at least three independent experiments with similar results.

TS/A and 4T1 tumor cells produce PGE2 in a cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2)-dependent manner

We were interested in determining the type of soluble factors produced by TS/A and 4T1 tumor cells that may be immunosuppressive. We measured PGE2, TGF-β1, and IL-10 using culture supernatant of these tumor cells. As a control, we used the murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7, which produces IL-12 p40 in response to stimulation by IFN-γ and LPS [45]. TS/A and 4T1 but not RAW264.7 cells produced large amounts of PGE2 (Fig. 2a) but no detectable levels of IL-10 (data not shown). Moreover, PGE2 production by the mammary tumor cells could be effectively blocked by the COX-2-specific inhibitor NS-398 (Fig. 2a), suggesting that COX-2 is responsible for the synthesis of a majority of PGE2 in TS/A and 4T1 cells. All cell lines also produced significant amounts of TGF-β1, which was not affected by the NS-398 treatment (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

PGE2 and TGF-β1 production by tumor cell lines. Murine mammary adenocarcinoma cell lines TS/A and 4T1 and myeloid leukemia cell line RAW264.7, all of BALB/c origins, were cultured, and supernatant was assayed by ELISA for production of PGE2 (a) and TGF-β1 (b) in the presence or absence of 2 × 10−5 M NS-398. Data are representative of three separate experiments. The effective concentration of NS-398 used was determined by titrations. Production of active TGF-β1 was measured by heating at 80°C for 10 min.

Tumor-derived PGE2 inhibits IL-12 production by peritoneal macrophages

We next investigated the possibility that soluble factors secreted by the tumor cells could inhibit IL-12 production by macrophages. We transferred culture supernatant of 4T1 cells to the culture of primary mouse peritoneal macrophages stimulated with IFN-γ and LPS (to produce IL-12). Figure 3a shows that the tumor cell media (TCM) of 4T1 cells was able to suppress IL-12 p70 production by macrophages dose-dependently, and 6% of transferred TCM was able to inhibit IL-12 production completely. The IC50 was approximately 1.5% of TCM, which translated into ∼1.4 nM based on the amount of PGE2 produced by 4T1 cells (Fig. 2a). The soluble factor(s) was not likely IL-10, as this cytokine was not measurable in the supernatant of 4T1 cells (data not shown). An experiment was designed to test if tumor cell-derived PGE2 was responsible for the observed inhibition of IL-12 production (Fig. 3b). Inhibition of PGE2 production by NS-398 treatment of the tumor cells completely restored IL-12 production inhibited by 4T1 cell culture-derived supernatant (Fig. 3c, NS-398+TCM). Moreover, the addition of exogenous PGE2 to unconditioned medium (NS-398+NM+PGE2) was able to mimic the effect of TCM in an NS-398-resistant manner. These results strongly suggest that PGE2 is an essential factor for the IL-12-inhibiting activity present in the tumor cell-culture supernatant.

Fig. 3.

PGE2 produced by 4T1 tumor cells inhibits IL-12 production by macrophages. (a) Murine peritoneal macrophages (Mφ) elicited by thioglycolate injection were cultured in normal media (NM) or increasing amounts (v:v) of TCM transferred from 4T1 cell cultures. Cells were immediately stimulated with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) for 16 h, followed by LPS (1 μg/ml) stimulation for 24 h. IL-12 p70 was assayed by ELISA. (b) Flowchart of the experimental design to test if PGE2 secreted by 4T1 tumor cells was responsible for inhibition of IL-12. (c) Peritoneal macrophages were cultured in the presence of NM or mixed with 3% TCM with or without NS-398 (2×10−5 M) treatment followed by stimulation with IFN-γ and LPS. Note that in the third bar from the top, NS-398 was added to the 4T1 cell culture, not to the macrophage culture. Data are representative of two independent experiments. PGE2 was dissolved in ethanol and added to a final concentration of 10−6 M in 1:1000 dilution (0.1% ethanol final). Control cultures received ethanol.

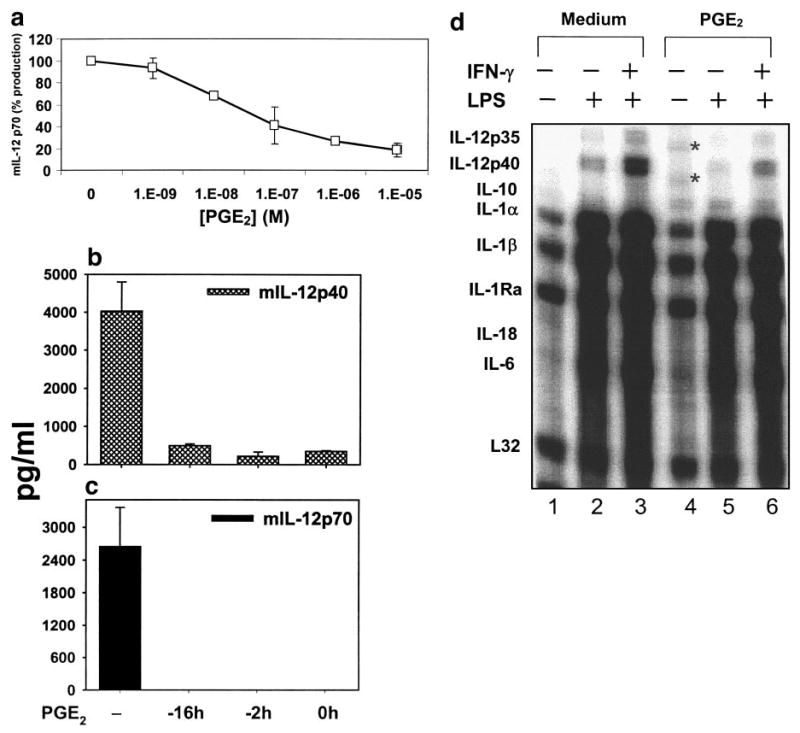

PGE2 inhibits IL-12 protein and mRNA expression

To further characterize the molecular mechanism whereby PGE2 inhibits IL-12 production by macrophages, we examined the dose response of PGE2 (Fig. 4a). PGE2 inhibited the level of IL-12 p70 in the culture supernatant of mouse peritoneal macrophages in a dose-dependent manner, resulting in ∼80% suppression at 10−5 M without toxicity to the cells. The IC50 was ∼50 nM. This estimated IC50 is considerably higher than that shown in Figure 3a (1.4 nM). The reason for this discrepancy is not clear but may be attributable to the use of different batches of PGE2 in separate experiments.

Fig. 4.

Dose and kinetics of PGE2-mediated inhibition of macrophage IL-12 production. (a) Dose dependency of PGE2. Thioglycolate-elicited murine macrophages were primed with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) for 16 h, followed by LPS (1 μg/ml) stimulation for 24 h. PGE2 was added at various concentrations as indicated. The production of IL-12 p70 was measured by ELISA, and the values were normalized to that of control (without PGE2) as percentages. (b) Kinetics of PGE2. PGE2 was added at 10−6 M to macrophage cultures stimulated as described (a) at different times. The time-points indicate the number of hours before LPS stimulation. ELISA was performed to measure IL-12 p40 (b) and p70 (c) production in culture supernatant. (d) RPA. Total RNA was isolated from peritoneal macrophages stimulated with LPS or IFN-γ plus LPS in vitro, together with PGE2 (10−6 M), added at the same time as LPS. RPA was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes 1–3, No PGE2; lanes 4–6, PGE2-treated. All results shown here are representative of two to three independent experiments with similar outcomes. *, Bands of incompletely digested probes.

We also determined the kinetics of PGE2-induced inhibition of the production of IL-12 p40 (Fig. 4b) and p70 (Fig. 4c) by adding PGE2 to the cell culture 16 h or 2 h before or at the time of LPS stimulation (0 h). PGE2 was able to suppress IL-12 production throughout these periods, suggesting that the effect of PGE2 is immediate and long-lasting, i.e., being able to interfere with LPS-initiated signaling simultaneously.

To evaluate the role of PGE2 in transcriptional regulation of IL-12 p40 and p35 genes at the mRNA level, we analyzed the steady-state mRNA expression of several cytokines produced by activated macrophages by a multiprobe RNase protection assay (Fig. 4d). LPS moderately, IFN-γ, and LPS strongly stimulated the mRNA expression of IL-12 p35 and p40 in peritoneal macrophages (lanes 2 and 3). Expression of IL-12 p35 and p40 mRNAs was inhibited by PGE2 treatment of LPS- and IFN-γ/LPS-activated macrophages (lanes 5 and 6). Expression of several other proinflammatory cytokine mRNAs was not significantly inhibited by PGE2: IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-18, and IL-6. These results are consistent with the general anti-inflammatory role of PGE2 in macrophages. We also examined the stability of IL-12 p35 and p40 mRNA following PGE2 treatment in the presence of actinomycin D and found no evidence of a role of PGE2 in the regulation of the decaying of these mRNAs (data not shown).

PGE2 inhibits IL-12 p40 at the level of transcription

To determine if the inhibitory effects of PGE2 on IL-12 protein and mRNA expression were transcriptional, we performed luciferase reporter assays to measure the mouse IL-12 p40 promoter activity in RAW264.7 cells following treatment with PGE2. The RAW264.7 cell line has been used widely by us and others for the investigation of macrophage-derived cytokine gene expression because of its easiness to transfect and its similarity to primary macrophages [45, 47, 48], in contrast to the difficulties in the transfection of primary macrophages. Figure 5a shows that the IL-12 p40 promoter-driven luciferase activity was induced by LPS, ∼32-fold compared with the unstimulated control (medium), which was further enhanced by IFN-γ priming, to ∼70-fold. The stimulation of the IL-12 p40 promoter by LPS or IFN-γ plus LPS was reduced strongly by PGE2 treatment. Similarly, LPS (eightfold) potently stimulated the promoter activity of TNF-α alone or by IFN-γ plus LPS (28-fold), and PGE2 treatment significantly reduced the magnitude of stimulation by these agents (Fig. 5b). These results demonstrate that PGE2 can exert its repressive effects on the expression of proinflammatory cytokines at the transcriptional level.

Fig. 5.

Transcriptional regulation of inflammatory cytokines by PGE2. The mouse IL-12 p40 promoter and human TNF-α promoter linked to the firefly luciferase reporter gene were transiently transfected into RAW264.7 cells by electroporation. Cells were then stimulated with IFN-γ (16 h) in the presence or absence of PGE2 (10−5 M) or an equal volume of ethanol (solvent) followed by LPS treatment (7 h). Cells were harvested, and lysates were prepared and used for luciferase assay. Relative luciferase activity is calculated as fold of induction comparing LPS or IFN-γ/LPS-stimulated promoter activity with that of unstimulated luciferase activity (medium), which is set as 1. (a) IL-12 p40 and (b) TNF-α. Data shown are combined from two independent experiments with sem.

PGE2-induced inhibition of IL-12 p40 gene expression is dependent on AP-1 activity

There is strong evidence suggesting that PGE2 can induce expression and activity of AP-1 directly, which consists of the proto-oncogenes c-Fos and c-Jun, in a number of cell types including macrophages [49–52]. AP-1 has been implicated as an inhibitor of IL-12 production by transcriptionally suppressing IL-12 p40 mRNA expression. This was demonstrated in c-Fos-deficient macrophages, which revealed a significant increase in IL-12 p70 protein, IL-12 p40 mRNA, and transcription rate in peritoneal macrophages stimulated with LPS [53]. Moreover, the enhancing effects on IL-12 production by pre-treatment of macrophages with IFN-γ and IL-4 have been attributed at least in part to the down-regulation of c-Fos by these two cytokines during the priming phase [53, 54].

To confirm the inhibitory effects of AP-1 on the IL-12 p40 gene expression, we used a dominant-negative mutant of AP-1, A-Fos, which was designed to contain an acidic, amphipathic protein sequence appended onto the N terminus of the Fos leucine zipper, replacing the normal basic region critical for DNA binding. The acidic extension and the Jun basic region form a heterodimeric coiled-coil structure that stabilizes the complex over 3000-fold and prevents the basic region of Jun from binding to DNA [55]. We measured the response of the endogenous IL-12 p40 gene by ELISA following transfection of the effector construct A-Fos (Fig. 6a, A) or its empty vector control, CMV500 (Fig. 6a, C) into RAW264.7 cells. IL-12 p40 secretion after LPS stimulation was dramatically enhanced by A-Fos expression without a visible impact on IL-12 p40 production stimulated with IFN-γ and LPS (Fig. 6a). We also examined the effects of A-Fos on the transcriptional response of the heterologous IL-12 p40 promoter reporter. Similarly, A-Fos greatly enhanced the response of the IL-12 p40 promoter to LPS stimulation without an impact on the IFN-γ/LPS-stimulated promoter activity (Fig. 6b). These results are consistent with the in vivo data showing that genetic deficiency of c-Fos renders macrophages more potent producers of IL-12 in response to LPS but not to IFN-γ plus LPS [53].

Fig. 6.

PGE2-induced and AP-1-mediated inhibition of IL-12 p40 gene expression. (a) Endogenous IL-12 p40 protein production is induced by A-Fos. Transient transfection into RAW264.7 cells was performed with the control vector CMV500 (C) or A-Fos (A). Supernatants were collected after LPS or IFN-γ plus LPS stimulation of the transfected cells. ELISA was performed to measure mIL-12 p40 secretion. Unstimulated cells produced no detectable levels of mIL-12 p40. The detection limit was 10 pg/ml. (b) A-Fos enhances IL-12 p40 transcription. Human IL-12 p40 promoter containing a 3.3-kb genomic sequence driving the firefly luciferase cDNA was transiently transfected into RAW264.7 cells by electroporation together with A-Fos (A) or its control vector CMV500 (C). Cells were stimulated with LPS or primed with IFN-γ for 15 h followed by LPS for 7 h. Cells were harvested, and lysates were prepared. Luciferase activity was measured. A summary of five separate experiments is shown with standard deviation. (c) A-Fos blocks the inhibition of IL-12 p40 production by PGE2 in RAW264.7 cells. Transient transfection into RAW264.7 cells was performed with an expression vector for A-Fos in the presence or absence of PGE2 (10−6 M). Supernatants were collected for ELISA after IFN-γ plus LPS stimulation of the transfected cells. The transfection efficiency was approximately 20%, evaluated by β-gal staining. The results shown here are a summary of two experiments with duplicate wells in each. (d) c-Fos and c-Jun inhibit IL-12 p40 transcription in RAW264.7 cells. Transient transfection in RAW264.7 cells was performed as in Figure 5. The IL-12 p40 promoter-luciferase reporter was cotransfected with c-Fos, c-Jun, or a combination with c-Fos and c-Jun at different ratios of effector:reporter, starting at 0 (no effector) and ending at a ratio of 0.5:1 with a constant amount of reporter. Luciferase activity was measured from cell lysates after stimulation with IFN-γ (16 h) and LPS (7 h). The control vector for c-Fos and c-Jun, CMV500, was used with the IL-12 p40 promoter, where no effector was used. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

We then investigated the role of AP-1 in PGE2-mediated inhibition of IL-12 production by transiently transfecting A-Fos into RAW264.7 cells activated by IFN-γ and LPS in the presence of PGE2. Figure 6c shows that PGE2 significantly inhibited IFN-γ/LPS-induced mIL-12 p40 production in this cell line. A-Fos expression in PGE2-treated RAW264.7 cells resulted in a completed reversal of its inhibitory effect, indicating that AP-1 is a critical mediator of the IL-12 p40-suppressing activity of PGE2.

Finally, we directly assessed the effects of AP-1 on transcriptional activity of the IL-12 p40 promoter by transiently cotransfecting the p40 reporter construct with a vector expressing c-Fos or c-Jun. As shown in Figure 6d, c-Fos expression inhibited IL-12 p40 transcription in a dose-dependent manner on a molar basis, and c-Jun did so only at the highest concentration in this experiment. Coexpression of c-Fos and c-Jun resulted in an additive inhibition of p40 transcription, demonstrating a suppressive role of AP-1 in IL-12 p40 gene expression.

Inhibition of PGE2 production in vivo enhances control of tumor progression and IL-12/IFN-γ production

We hypothesized that as NS-398, a pharmacological inhibitor of COX-2 activity and PGE2 synthesis, is able to restore IL-12 production in vitro in macrophages, it may also be able to do so in vivo, leading to enhancement of tumor regression and/or reduction in metastasis in analogy to the effects of IL-12 administration in mammary tumor models.

To test this hypothesis, we treated 4T1 tumor-bearing mice with NS-398, IL-12, or NS-398 and IL-12 and measured the tumor growth and lung metastasis. NS-398 treatment did not slow the growth of the 4T1 tumor significantly compared with IL-12 treatment (Fig. 7a). The combined use of IL-12 and NS-398 had a generally similar effect to the use of IL-12 alone. NS-398 treatment did reduce metastatic 4T1 cells in the lung by an order of magnitude (Fig. 7b), and IL-12 treatment completely blocked lung metastases.

Fig. 7.

Inhibition of 4T1 tumor growth by IL-12. (a) 4T1 tumor cells (105) were injected s.c. in the abdominal mammary gland with 0.1 ml of a single-cell suspension containing the indicated number of cells. Tumor growth was monitored every 2–3 days. NS-398 or IL-12 was given (1 μg) i.p. on Day 7 when the tumor size was ∼5 mm in diameter and every other day after that until Day 21 when the mice were killed. Each group was comprised of five mice. (b) Lung metastasis was measured at the end of this experiment (Day 21) by the 6-thioguanine clonogenic assay [56]. (c) Peritoneal macrophages taken from the mice-bearing 4T1 tumor, treated with or without NS-398 in vivo, were stimulated or not in vitro with IFN-γ and LPS (IFN-γ/LPS) for 24 h. ELISA was performed to measure IL-12 p40 production in cell-free supernatant. (d) Splenocytes from the four groups of mice (107 cells/ml) were harvested 21 days after tumor injection, cultured, and stimulated with or without Concanavalin A (ConA) for 24 h. IFN-γ production in the supernatant was measured by ELISA.

In addition, we assessed the ability of peritoneal macrophages derived from tumor-bearing mice to produce IL-12 following NS-398 treatment (Fig. 7c), which indicated that IL-12 production, stimulated by IFN-γ and LPS in vitro, was strongly enhanced by this treatment. To measure IFN-γ production in response to IL-12 and NS-398 treatments, we used splenocytes, as they contain T lymphocytes, which are the major source of IFN-γ. The IL-12 and NS-398 treatments resulted in greater IFN-γ production from the splenocytes isolated from tumor-bearing mice following ConA stimulation in vitro (Fig. 7d), although the splenocytes from IL-12-treated animals were able to produce large amounts of IFN-γ without further in vitro stimulation. Taken together, these results indicate that the NS-398 treatment partially restored the immune capacity of the host with respect to IL-12 and IFN-γ production and antimetastasis.

Discussion

We provide the first demonstration that the inhibition of IL-12 production by PGE2 in macrophages is conferred on the p40 gene at the level of transcription (Fig. 5a). The similar degrees of inhibition of IL-12 p40 expression at the level of protein (Fig. 4, a and b), mRNA (Fig. 4d), and transcription (Fig. 5a) suggest that PGE2 exerts its suppressive effect primarily on the transcription of the IL-12 p40 gene. Furthermore, this inhibition is dependent on the presence of a functional AP-1 (Fig. 6c). AP-1 is an immediate, early response factor involved in a diverse set of transcriptional regulatory processes [57]. As a target for positive regulation by the mitogen-activated protein and Jun kinase cascades, AP-1 components have been implicated as downstream effectors in transformation by a number of oncogenes [55, 58–60]. PGE2 production has also been shown to be critically dependent on transcriptional activation by AP-1 [61–65]. Thus, AP-1 and PGE2 may form a functional amplification loop that perpetuates one another's expression in tumor or tumor-associated cells in an autocrine or paracrine manner. Our results about the regulatory relationship between PGE2 and IL-12 via AP-1 may have implications in terms of the mechanistic basis for oncogenic progression via immunosuppression.

Xin and Sriram [66] have previously shown that vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), a naturally occurring neuropeptide widely distributed in the nervous system and a ligand for G protein-coupled receptors, inhibits production of IL-12 and nitric oxide (NO) but not TNF-α production in macrophages stimulated with LPS or superantigens. The inhibitory effect of VIP on IL-12 production is cAMP-mediated [66]. Delgado and Ganea [67] further demonstrated that VIP inhibits IL-12 p40 transcription by regulating nuclear factor (NF)-κB and Ets activation. Thus, it is possible that PGE2-induced inhibition of IL-12 p40 transcription may also target NF-κB- and Ets-related factors. An additional and significant player that might be involved in PGE2-induced inhibition of IL-12 p40 transcription is the inducible cAMP early repressor (ICER), which belongs to the cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) [68] and cAMP response-element modulator [69] family of the basic leucine zipper transcription factors and acts as a dominant-negative regulator of cAMP-responsive transcription [70]. In the case of the IL-2 gene induction during T cell activation, the presence of ICER before T cell activation is purported to form a transcriptionally inactive complex with NF of activated T cells (NFAT) on the IL-2 promoter, which fails to recruit CREB-binding protein, resulting in transcriptional inhibition [71]. The relevance of ICER to PGE2-induced transcriptional repression of the IL-12 p40 gene is supported by the observation that NFAT is involved in the mIL-12 p40 transcriptional activation with a member of the IFN regulatory factor family of transcription factors, IFN consensus sequence-binding protein [72].

In the in vivo experimentation, it is noted that NS-398 treatment, although substantial in terms of its effect on metastasis compared with the control group [a tenfold reduction (Fig. 7b) ], did not display as potent anti-tumor activities as those elicited by the IL-12 treatment. Another group applied the same regimen to the Lewis lung carcinoma (3LL) model with remarkable efficacy [30]. In this model, inhibition of COX-2 led to marked lymphocytic infiltration of the tumor and reduced tumor growth. Treatment of mice with anti-PGE2 monoclonal antibody replicated the growth reduction seen in tumor-bearing mice treated with COX-2 inhibitors. COX-2 inhibition was accompanied by a significant decrease in IL-10 and a concomitant restoration of IL-12 production by antigen-presenting cells [30]. The discrepancy might be explained by the possibility of a quantitative difference with respect to how much endogenous IL-12 was induced by the NS-398 treatment compared with the exogenous administration of rIL-12 at 1 μg every other day and by the fact that NS-398 and IL-12 were given to the animals at the same time on Day 7. NS-398 may need longer time to deliver its effects than the direct application of IL-12, as NS-398 works by blocking COX-2 first, which leads to a decreased level of PGE2 synthesis and ultimately, some restoration of endogenous IL-12 production. Third, as shown in Figure 2b, NS-398 treatment does not have any effect on the production of TGF-β by mammary tumor cells, which could explain in part a possible lack of full restoration of the production of endogenous IL-12. Finally, the lack of equivalent efficacy of NS-398 treatment could be a result of an impairment of IL-12 receptor (IL-12R) expression in the immune cells (NK cells, T cells, macrophages, and DC) of tumor-bearing mice, which were not fully restored by NS-398 treatment but were better restored by exogenous IL-12 treatment. Exposure of committed Th2 cells to IL-12 has been shown to be able to restore their full IL-12 responsiveness by up-regulating IL-12R expression [73]. Alternatively, the inability of NS-398 to fully mimic the effects of exogenous IL-12 may not be attributable to simple, quantitative differences in IL-12 abundance. The consistent, additive effects of NS-398 to those of exogenous IL-12 (Fig. 7, a and d) could suggest IL-12-independent contributions of COX-2 inhibition. Elevated PGE2 production is a common feature of human malignancies. This has been attributed to increased COX-2 expression and activity [74–76]. It has been shown that PGE2 suppresses NK activity in vivo and promotes postoperative tumor metastasis in rats [77]. One noticeable effect of NS-398 was the ability to stimulate IFN-γ production in the spleen of the treated mice (Fig. 7d), which correlated with the significant efficacy of NS-398 in the suppression of lung metastasis of the 4T1 tumor. IFN-γ has been shown in the 4T1 tumor model to be a critical factor for the inhibition of metastasis [56, 78], although the mechanism by which IFN-γ suppresses metastasis remains to be determined.

The role of TGF-β in tumor growth and metastasis is also an important issue that should not be overlooked in our system, as 4T1 and TS/A tumor cells produce large amounts of TGF-β (Fig. 2b). The effects of TGF-β in the biology of epithelial cells are complex. TGF-β is a potent inhibitor of epithelial cell proliferation [79]. However, in established carcinomas, autocrine/paracrine TGF-β interactions can enhance tumor cell viability, migration, and metastases [80]. Treatment of 4T1 tumor-bearing animals with IFN-γ or antisense TGF-β gene-modified tumor cell vaccines reduced the number of clonogenic metastases to the lungs and liver [56]. The lesser effects of NS-398 compared with IL-12 could be accounted for, at least in part, by the presence of TGF-β. In this context, it is interesting to note that peritoneal macrophages from IL-12p40 gene knockout mice have a bias toward the M2 profile, spontaneously secreting large amounts of TGF-β1 and responding to rIFN-γ with weak NO production, suggesting that IL-12 is a natural inhibitor of TGF-β synthesis and/or activity.

The apparent discrepancy between our data, showing that systemic administration of rIL-12 could inhibit primary 4T1 tumor growth (Fig. 1), and that of Rakhmilevich et al. [42], showing an inability of tumor-derived rIL-12 to suppress intradermal 4T1 tumor growth, could be reconciled by the observation of Cavallo et al. [81], who compared the effects of local and systemic rIL-12 application in mice harboring the TS/A tumor. Whereas the immune events elicited via the two routes of rIL-12 administration seem to be the same, systemic rIL-12 is markedly more effective because of its ability to promptly elicit an antitumor response that is dependent on the cooperation of several key factors: indirect inhibition of angiogenesis by secondary cytokines (mainly IFN-γ) and third-level chemokines (inducible protein 10 and monokine induced by IFN-γ); systemic activation of leukocyte subsets capable of producing proinflammatory cytokines, CTL, and antitumor antibodies; and destruction of tumor vessels by polymorphonuclear cells [81].

In summary, our study provides mechanistic evidence about the way tumor-derived PGE2 inhibits the expression of a crucial immune regulator, thus weakening the immune competence of the host. The information obtained from this study contributes to the overall effort to understand the host versus tumor interactions and to develop more effective strategies for cancer immunotherapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (AI45899) to X. M. S. C. was supported by a Fellowship from the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation. M. M. and J. L. contributed equally to this study.

References

- 1.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12: a proinflammatory cytokine with immunoregulatory functions that bridge innate resistance and antigen-specific adaptive immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:251–276. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trinchieri G, Scott P. Interleukin-12: basic principles and clinical applications. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1999;238:57–78. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-09709-0_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rook AH, Wood GS, Yoo EK, Elenitsas R, Kao DM, Sherman ML, Witmer WK, Rockwell KA, Shane RB, Lessin SR, Vonderheid EC. Interleukin-12 therapy of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma induces lesion regression and cytotoxic T-cell responses. Blood. 1999;94:902–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rook AH, Zaki MH, Wysocka M, Wood GS, Duvic M, Showe LC, Foss F, Shapiro M, Kuzel TM, Olsen EA, Vonderheid EC, Laliberte R, Sherman ML. The role for interleukin-12 therapy of cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;941:177–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ansell SM, Witzig TE, Kurtin PJ, Sloan JA, Jelinek DF, Howell KG, Markovic SN, Habermann TM, Klee GG, Atherton PJ, Erlichman C. Phase 1 study of interleukin-12 in combination with rituximab in patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2002;99:67–74. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mortarini R, Borri A, Tragni G, Bersani I, Vegetti C, Bajetta E, Pilotti S, Cerundolo V, Anichini A. Peripheral burst of tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes and infiltration of metastatic lesions by memory CD8+ T cells in melanoma patients receiving interleukin 12. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3559–3568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gollob JA, Mier JW, Veenstra K, McDermott DF, Clancy D, Clancy M, Atkins MB. Phase I trial of twice-weekly intravenous interleukin 12 in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer or malignant melanoma: ability to maintain IFN-γ induction is associated with clinical response. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1678–1692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee P, Wang F, Kuniyoshi J, Rubio V, Stuges T, Groshen S, Gee C, Lau R, Jeffery G, Margolin K, Marty V, Weber J. Effects of interleukin-12 on the immune response to a multipeptide vaccine for resected metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3836–3847. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.18.3836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang WK, Park C, Yoon HL, Kim WS, Yoon SS, Lee MH, Park K, Kim K, Jeong HS, Kim JA, Nam SJ, Yang JH, Son YI, Baek CH, Han J, Ree HJ, Lee ES, Kim SH, Kim DW, Ahn YC, Huh SJ, Choe YH, Lee JH, Park MH, Kong GS, Park EY, Kang YK, Bang YJ, Paik NS, Lee SN, Kim SH, Kim S, Robbins PD, Tahara H, Lotze MT, Park CH. Interleukin 12 gene therapy of cancer by peritumoral injection of transduced autologous fibroblasts: outcome of a phase I study. Hum Gene Ther. 2001;12:671–684. doi: 10.1089/104303401300057388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gajewski TF, Fallarino F, Ashikari A, Sherman M. Immunization of HLA-A2+ melanoma patients with MAGE-3 or MelanA peptide-pulsed autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cells plus recombinant human interleukin 12. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:895s–901s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Portielje JE, Kruit WH, Schuler M, Beck J, Lamers CH, Stoter G, Huber C, de Boer-Dennert M, Rakhit A, Bolhuis RL, Aulitzky WE. Phase I study of subcutaneously administered recombinant human interleukin 12 in patients with advanced renal cell cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:3983–3989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma X, Trinchieri G. Regulation of interleukin-12 production in antigen-presenting cells. Adv Immunol. 2001;79:55–92. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(01)79002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Handel-Fernandez ME, Cheng X, Herbert LM, Lopez DM. Down-regulation of IL-12, not a shift from a T helper-1 to a T helper-2 phenotype, is responsible for impaired IFN-γ production in mammary tumor-bearing mice. J Immunol. 1997;158:280–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sica A, Saccani A, Bottazzi B, Polentarutti N, Vecchi A, van Damme J, Mantovani A. Autocrine production of IL-10 mediates defective IL-12 production and NF- κ B activation in tumor-associated macrophages. J Immunol. 2000;164:762–767. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elgert KD, Alleva DG, Mullins DW. Tumor-induced immune dysfunction: the macrophage connection. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;64:275–290. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong JH, Renz H, Sprenger H, Nain M, Gemsa D. Enhancement of tumor necrosis factor-α gene expression by low doses of prostaglandin E2 and cyclic GMP. Immunobiology. 1990;182:44–55. doi: 10.1016/s0171-2985(11)80582-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohmori Y, Strassman G, Hamilton TA. cAMP differentially regulates expression of mRNA encoding IL-1 α and IL-1 β in murine peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol. 1990;145:3333–3339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams JA, Shacter E. Regulation of macrophage cytokine production by prostaglandin E2. Distinct roles of cyclooxygenase-1 and -2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25693–25699. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vial D, Arbibe L, Havet N, Dumarey C, Vargaftig B, Touqui L. Down-regulation by prostaglandins of type-II phospholipase A2 expression in guinea-pig alveolar macrophages: a possible involvement of cAMP. Biochem J. 1998;330:89–94. doi: 10.1042/bj3300089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D'Acquisto F, Sautebin L, Iuvone T, Di Rosa M, Carnuccio R. Prostaglandins prevent inducible nitric oxide synthase protein expression by inhibiting nuclear factor- κB activation in J774 macrophages. FEBS Lett. 1998;440:76–80. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett A, Charlier EM, McDonald AM, Simpson JS, Stamford IF, Zebro T. Prostaglandins and breast cancer. Lancet. 1977;2:624–626. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)92496-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bennett A, Berstock DA, Raja B, Stamford IF. Survival time after surgery is inversely related to the amounts of prostaglandins extracted from human breast cancers [proceedings ] Br J Pharmacol. 1979;66:451P. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rolland PH, Martin PM, Jacquemier J, Rolland AM, Toga M. Prostaglandin in human breast cancer: evidence suggesting that an elevated prostaglandin production is a marker of high metastatic potential for neoplastic cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1980;64:1061–1070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bennett A, Stamford IF, Berstock DA, Dische F, Singh L, A'Hern RP. Breast cancer, prostaglandins and patient survival. Br J Cancer. 1989;59:268–275. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1989.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Pouw Kraan TC, Boeije LC, Smeenk RJ, Wijdenes J, Aarden LA. Prostaglandin-E2 is a potent inhibitor of human interleukin 12 production. J Exp Med. 1995;181:775–779. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uotila P. The role of cyclic AMP and oxygen intermediates in the inhibition of cellular immunity in cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1996;43:1–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03354243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu CY, Wang K, McDyer JF, Seder RA. Prostaglandin E2 and dexamethasone inhibit IL-12 receptor expression and IL-12 responsiveness. J Immunol. 1998;161:2723–2730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Szabo G, Girouard L, Mandrekar P, Catalano D. Regulation of monocyte IL-12 production: augmentation by lymphocyte contact and acute ethanol treatment, inhibition by elevated intracellular cAMP. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1998;20:491–503. doi: 10.1016/s0192-0561(98)00046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monteleone G, Parrello T, Monteleone I, Tammaro S, Luzza F, Pallone F. Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) regulate differently IL-12 production in human intestinal lamina propria mononuclear cells (LPMC) Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;117:469–475. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00991.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stolina M, Sharma S, Lin Y, Dohadwala M, Gardner B, Luo J, Zhu L, Kronenberg M, Miller PW, Portanova J, Lee JC, Dubinett SM. Specific inhibition of cyclooxygenase 2 restores antitumor reactivity by altering the balance of IL-10 and IL-12 synthesis. J Immunol. 2000;164:361–370. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harizi H, Juzan M, Grosset C, Rashedi M, Gualde N. Dendritic cells issued in vitro from bone marrow produce PGE(2) that contributes to the immunomodulation induced by antigen-presenting cells. Cell Immunol. 2001;209:19–28. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2001.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harizi H, Juzan M, Pitard V, Moreau JF, Gualde N. Cyclooxygenase-2-issued prostaglandin e(2) enhances the production of endogenous IL-10, which down-regulates dendritic cell functions. J Immunol. 2002;168:2255–2263. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Narumiya S, Sugimoto Y, Ushikubi F. Prostanoid receptors: structures, properties, and functions. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:1193–1226. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wright DH, Abran D, Bhattacharya M, Hou X, Bernier SG, Bouayad A, Fouron JC, Vazquez-Tello A, Beauchamp MH, Cly-man RI, Peri K, Varma DR, Chemtob S. Prostanoid receptors: ontogeny and implications in vascular physiology. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;281:R1343–R1360. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.5.R1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nanni P, de Giovanni C, Lollini PL, Nicoletti G, Prodi G. TS/A: a new metastasizing cell line from a BALB/c spontaneous mammary adenocarcinoma. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1983;1:373–380. doi: 10.1007/BF00121199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giovarelli M, Santoni A, Forni G. Alloantigen-activated lymphocytes from mice bearing a spontaneous “nonimmunogenic” adenocarcinoma inhibit its growth in vivo by recruiting host immunoreactivity. J Immunol. 1985;135:3596–3603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferrantini M, Giovarelli M, Modesti A, Musiani P, Modica A, Venditti M, Peretti E, Lollini PL, Nanni P, Forni G, et al. IFN-α 1 gene expression into a metastatic murine adenocarcinoma (TS/A) results in CD8+ T cell-mediated tumor rejection and development of antitumor immunity. Comparative studies with IFN-γ-producing TS/A cells. J Immunol. 1994;153:4604–4615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cavallo F, Signorelli P, Giovarelli M, Musiani P, Modesti A, Brunda MJ, Colombo MP, Forni G. Antitumor efficacy of adenocarcinoma cells engineered to produce interleukin 12 (IL-12) or other cytokines compared with exogenous IL-12. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1049–1058. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.14.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller FR, Miller BE, Heppner GH. Characterization of metastatic heterogeneity among subpopulations of a single mouse mammary tumor: heterogeneity in phenotypic stability. Invasion Metastasis. 1983;3:22–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pulaski BA, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Reduction of established spontaneous mammary carcinoma metastases following immunotherapy with major histocompatibility complex class II and B7.1 cell-based tumor vaccines. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1486–1493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aslakson CJ, Miller FR. Selective events in the metastatic process defined by analysis of the sequential dissemination of subpopulations of a mouse mammary tumor. Cancer Res. 1992;52:1399–1405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rakhmilevich AL, Janssen K, Hao Z, Sondel PM, Yang NS. Interleukin-12 gene therapy of a weakly immunogenic mouse mammary carcinoma results in reduction of spontaneous lung metastases via a T- cell-independent mechanism. Cancer Gene Ther. 2000;7:826–838. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Plevy SE, Gemberling JH, Hsu S, Dorner AJ, Smale ST. Multiple control elements mediate activation of the murine and human interleukin 12 p40 promoters: evidence of functional synergy between C/EBP and Rel proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4572–4588. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grazia Cappiello M, Sutterwala FS, Trinchieri G, Mosser DM, Ma X. Suppression of IL-12 transcription in macrophages following Fc γ receptor ligation. J Immunol. 2001;166:4498–4506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma X, Chow JM, Gri G, Carra G, Gerosa F, Wolf SF, Dzialo R, Trinchieri G. The interleukin 12 p40 gene promoter is primed by interferon γ in monocytic cells. J Exp Med. 1996;183:147–157. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schreiber E, Matthias P, Muller MM, Schaffner W. Rapid detection of octamer binding proteins with ‘mini-extracts’, prepared from a small number of cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:6419. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.15.6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma X, Neurath M, Gri G, Trinchieri G. Identification and characterization of a novel Ets-2-related nuclear complex implicated in the activation of the human interleukin-12 p40 gene promoter. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10389–10395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cao S, Liu J, Chesi M, Bergsagel PL, Ho IC, Donnelly RP, Ma X. Differential regulation of IL-12 and IL-10 gene expression in macrophages by the basic leucine zipper transcription factor c-Maf fibrosarcoma. J Immunol. 2002;169:5715–5725. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simonson MS, Herman WH, Dunn MJ. PGE2 induces c-fos expression by a cAMP-independent mechanism in glomerular mesangial cells. Exp Cell Res. 1994;215:137–144. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lacroix S, Vallieres L, Rivest S. c-Fos mRNA pattern and corticotropin-releasing factor neuronal activity throughout the brain of rats injected centrally with a prostaglandin of E2 type. J Neuroimmunol. 1996;70:163–179. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(96)00114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Won JS, Suh HW, Kim YH, Song DK, Huh SO, Lee JK, Lee KJ. Prostaglandin E2 increases proenkephalin mRNA level in rat astrocyte-enriched culture. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;60:203–214. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00182-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iwahashi H, Takeshita A, Hanazawa S. Prostaglandin E2 stimulates AP-1-mediated CD14 expression in mouse macrophages via cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase A. J Immunol. 2000;164:5403–5408. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.5403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roy S, Charboneau R, Cain K, DeTurris S, Melnyk D, Barke RA. Deficiency of the transcription factor c-fos increases lipopolysac-charide-induced macrophage interleukin 12 production. Surgery. 1999;126:239–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roy S, Charboneau R, Melnyk D, Barke RA. Interleukin-4 regulates macrophage interleukin-12 protein synthesis through a c-Fos mediated mechanism. Surgery. 2000;128:219–224. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.108063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Olive M, Krylov D, Echlin DR, Gardner K, Taparowsky E, Vinson C. A dominant negative to activation protein-1 (AP1) that abolishes DNA binding and inhibits oncogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18586–18594. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu RS, Kobie JJ, Besselsen DG, Fong TC, Mack VD, McEarchern JA, Akporiaye ET. Comparative analysis of IFN-γ B7.1 and antisense TGF-β gene transfer on the tumorigenicity of a poorly immunogenic metastatic mammary carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2001;50:229–240. doi: 10.1007/s002620100197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Herschman HR. Primary response genes induced by growth factors and tumor promoters. Annu Rev Biochem. 1991;60:281–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.60.070191.001433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smeal T, Binetruy B, Mercola DA, Birrer M, Karin M. Oncogenic and transcriptional cooperation with Ha-Ras requires phosphorylation of c-Jun on serines 63 and 73. Nature. 1991;354:494–496. doi: 10.1038/354494a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pulverer BJ, Kyriakis JM, Avruch J, Nikolakaki E, Woodgett JR. Phosphorylation of c-jun mediated by MAP kinases. Nature. 1991;353:670–674. doi: 10.1038/353670a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mechta F, Lallemand D, Pfarr CM, Yaniv M. Transformation by ras modifies AP1 composition and activity. Oncogene. 1997;14:837–847. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dendorfer U, Oettgen P, Libermann TA. Multiple regulatory elements in the interleukin-6 gene mediate induction by prostaglandins, cyclic AMP, and lipopolysaccharide. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4443–4454. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen C, Chen YH, Lin WW. Involvement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in lipopolysaccharide-induced iNOS and COX-2 expression in J774 macrophages. Immunology. 1999;97:124–129. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00747.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Allport VC, Slater DM, Newton R, Bennett PR. NF- κB and AP-1 are required for cyclo-oxygenase 2 gene expression in amnion epithelial cell line (WISH) Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6:561–565. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.6.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Subbaramaiah K, Lin DT, Hart JC, Dannenberg AJ. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ ligands suppress the transcriptional activation of cyclooxygenase-2. Evidence for involvement of activator protein-1 and CREB-binding protein/p300. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12440–12448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007237200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Subbaramaiah K, Norton L, Gerald W, Dannenberg AJ. Cyclooxygenase-2 is overexpressed in HER-2/neu-positive breast cancer: evidence for involvement of AP-1 and PEA3. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:18649–18657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111415200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xin Z, Sriram S. Vasoactive intestinal peptide inhibits IL-12 and nitric oxide production in murine macrophages. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;89:206–212. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Delgado M, Ganea D. Vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide inhibit interleukin-12 transcription by regulating nuclear factor κB and Ets activation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31930–31940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.31930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hoeffler JP, Meyer TE, Yun Y, Jameson JL, Habener JF. Cyclic AMP-responsive DNA-binding protein: structure based on a cloned placental cDNA. Science. 1988;242:1430–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.2974179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Foulkes NS, Borrelli E, Sassone-Corsi P. CREM gene: use of alternative DNA-binding domains generates multiple antagonists of cAMP-induced transcription. Cell. 1991;64:739–749. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90503-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Molina CA, Foulkes NS, Lalli E, Sassone-Corsi P. Inducibility and negative autoregulation of CREM: an alternative promoter directs the expression of ICER, an early response repressor. Cell. 1993;75:875–886. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90532-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bodor J, Bodorova J, Gress RE. Suppression of T cell function: a potential role for transcriptional repressor ICER. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:774–779. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.6.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhu C, Rao K, Xiong H, Gagnidze K, Li F, Horvath C, Plevy S. Activation of the murine interleukin-12 p40 promoter by functional interactions between NFAT and ICSBP. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39372–39382. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306441200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Smits HH, van Rietschoten JG, Hilkens CM, Sayilir R, Stiekema F, Kapsenberg ML, Wierenga EA. IL-12-induced reversal of human Th2 cells is accompanied by full restoration of IL-12 responsiveness and loss of GATA-3 expression. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1055–1065. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200104)31:4<1055::aid-immu1055>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Taketo MM. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in tumorigenesis (part I) J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1529–1536. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.20.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Taketo MM. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in tumorigenesis (Part II) J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1609–1620. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.21.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kundu N, Yang Q, Dorsey R, Fulton AM. Increased cyclo-oxygenase-2 (cox-2) expression and activity in a murine model of metastatic breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2001;93:681–686. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yakar I, Melamed R, Shakhar G, Shakhar K, Rosenne E, Abudar-ham N, Page GG, Ben-Eliyahu S. Prostaglandin e(2) suppresses NK activity in vivo and promotes postoperative tumor metastasis in rats. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:469–479. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Clements VK, Terabe M, Park JM, Berzofsky JA, Dissanayake SK. Resistance to metastatic disease in STAT6-deficient mice requires hemopoietic and nonhemopoietic cells and is IFN-γ dependent. J Immunol. 2002;169:5796–5804. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Massague J. TGF-β signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:753–791. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Muraoka RS, Dumont N, Ritter CA, Dugger TC, Brantley DM, Chen J, Easterly E, Roebuck LR, Ryan S, Gotwals PJ, Koteliansky V, Arteaga CL. Blockade of TGF-β inhibits mammary tumor cell viability, migration, and metastases. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1551–1559. doi: 10.1172/JCI15234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cavallo F, Di Carlo E, Butera M, Verrua R, Colombo MP, Musiani P, Forni G. Immune events associated with the cure of established tumors and spontaneous metastases by local and systemic interleukin 12. Cancer Res. 1999;59:414–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]