Abstract

Background

Microglia are the major inflammatory cells in the central nervous system and play a role in brain injuries as well as brain diseases. In this study, we determined the role of microglia in ethanol’s apoptotic action on neuronal cells obtained from the mediobasal hypothalamus and maintained in primary cultures. We also tested the effect of cAMP, a signaling molecule critically involved in hypothalamic neuronal survival, on microglia-mediated ethanol’s neurotoxic action.

Methods

Ethanol’s neurotoxic action was determined on enriched fetal mediobasal hypothalamic neuronal cells with or without microglia cells or ethanol-activated microglia conditioned media. Ethanol’s apoptotic action was determined using nucleosome assay. Microglia activation was determined using OX6 histochemistry and by measuring inflammatory cytokines secretion from microglia in cultures using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). An immunoneutralization study was conducted to identify the role of a cytokine involved in ethanol’s apoptotic action.

Results

We show here that ethanol at a dose range of 50 and 100 mM induces neuronal death by an apoptotic process. Ethanol’s ability to induce an apoptotic death of neurons is increased by the presence of ethanol-activated microglia conditioned media. In the presence of ethanol, microglia showed elevated secretion of various inflammatory cytokines, of which TNF-α shows significant apoptotic action on mediobasal hypothalamic neuronal cells. Ethanol’s neurotoxic action was completely prevented by cAMP. The cell-signaling molecule also prevented ethanol-activated microglial production of TNF-α. Immunoneutralization of TNF-α prevented microglia-derived media’s ability to induce neuronal death.

Conclusions

These results suggest that ethanol’s apoptotic action on hypothalamic neuronal cells might be mediated via microglia, possibly via increased production of TNF-α. Furthermore, cAMP reduces TNF-α production from microglia to prevent ethanol’s neurotoxic action.

Neurotoxic action of alcohol during the developmental period is well documented. Prenatal administration of ethanol reduces the number of hippocampal neurons (Miller, 1995; Moulder et al., 2002), cortical neurons (Jacobs and Miller, 2001), cerebral granule and Purkinje neurons (Light et al., 2002; Maier et al., 1999), and hypothalamic neurons (De et al., 2004; Sarkar et al., 2007). It has also been shown that prenatal ethanol exposure produces injury to many neuroendocrine neurons in the hypothalamus and induces permanent changes in the stress axis and immune function in the fetal alcohol exposed offspring. (Hellemans et al., 2008; Sarkar et al., 2007; 2008). Of these neuroendocrine neurons, hypothalamic β-endorphin neurons appear to be a target of ethanol. Upon ethanol exposure during fetal life, a large number of these neurons undergo cell death by an apoptotic process (Chen et al., 2006). The mechanism by which β-endorphin neurons and other hypothalamic neurons in the mediobasal region (containing β-endorphin and a limited number of other neuroendocrine neurons) undergo apoptosis following ethanol exposure is not clearly understood.

A role for microglia in ethanol’s neurotoxic action in the adult brain has been identified (Crews et al., 2006; Fernandez-Lizarbe et al., 2009; Narita et al., 2007; Suk, 2007; Toyama et al., 2008; Watari et al., 2006). Microglial cells are the major inflammatory cells in the central nervous system and play a role in brain injuries as well as brain diseases. While some microglial functions are beneficial, recent studies suggest that microglia that are chronically activated are neurotoxic (Henkel et al., 2009). Moreover, some cytokines released by activated glial cells are considered to be candidate neurotoxins (Ramirez et al., 2008). Microglial cells produce tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, which is a well-known proinflammatory substance. It is well-known that microglia cells produce various other cytokines including interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α and MIP-2. Whether ethanol causes apoptosis in immature mediobasal hypothalamic (MBH) neurons by activating the microglia and release of these proinflammatory cytokines is not known.

Previously, it has been shown that cAMP down-regulates the release of proinflammatory and neurotoxic cytokines from microglial cells (Suzumura et al., 1999). However, whether cAMP prevents microglia activation and protects ethanol-induced apoptotic neuronal death in fetuses is not known. Chronic ethanol treatment has been shown to reduce cAMP levels in β-endorphin neurons of the fetal hypothalamus as a consequence of the desensitization of stimulatory G protein-coupled receptors (such as adenosine A2 receptors) seen following prolonged receptor activation (Hack and Christie, 2003). In the cells of the fetal hypothalamus, ethanol increases TGF-β1 production and/or release by reducing cAMP levels in β-endorphin neurons (Chen et al., 2006). A cAMP analog, dibutryl adenosine 3',5'-cyclic monophosphate (dbcAMP) has been shown to block ethanol’s activation of TGF-β1 in these neurons. TGF-β1 increases apoptosis in β-endorphin neurons via upregulating pro-apoptotic proteins but suppressing antiapoptotic proteins (Sarkar et al., 2007). Hence, the possibility arose that if microglia mediate ethanol-induced apoptotic death of β-endorphin neurons, dbcAMP might be able to prevent microglia activation and mediobasal hypothalamus (MBH) neuronal death. Using an in vitro neuron and microglia coculture model system, we determined whether ethanol activate microglia to increase the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines to cause cell death of developing MBH neurons. Furthermore, we evaluated whether cAMP prevents ethanol activation of microglia and decreases the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and apoptotic cell death of developing MBH neurons in cultures. We used a coculture model system consisting of fetal MBH neurons and fetal cortical-derived microglia. We have employed microglia from the cerebral cortex since they are more abundant in this tissue than in the hypothalamus and are well characterized (Lee et al., 2004). Furthermore, in vivo condition microglia cells are quite mobile and they move from one area of the brain to another area particularly during neurodegeneration (Bruce-Keller et al., 1999; Thomas, 1990; Zelivyanskaya et al., 2003) and in response to inflammatory cues (Rezaie et al., 2002). Additionally, microglial cells have been shown to penetrate into and scatter throughout the cortical grey and white matter as well as the diencephalon during the first 2 trimesters of gestation (Monier et al., 2007) suggesting that microglia cells from other parts of the brain can migrate to the hypothalamus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Use

Pregnant Sprague-Dawley female rats were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) and were used as the source of fetal rat brains for MBH cell and microglia cell cultures. Animal surgery and care were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines and complied with the National Institutes of Health policy. The animal protocol used was approved by the Rutgers Animal Care and Facilities Committee.

Enriched MBH neuronal cultures

In brief, pregnant rats at 18 to 20 days of gestation were sacrificed, and the fetuses were removed by aseptic surgical procedure. Brains from the fetuses were immediately removed and the hypothalami were separated and placed in ice-cold Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) containing antibiotic solution (100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 250 ng/ml amphotericin B), 0.1% bovine serum albumin, and 200 µM ascorbic acid (all from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The block of hypothalamic tissue consisted of the mediobasal portion of the hypothalamus and extended approximately 1 mm rostral to the optic chiasma and just caudal to the mammillary bodies, laterally to the hypothalamic sulci, and dorsally to ~2 mm deep. This part of the hypothalamus is known to contain neuroendocrine neurons, including β-endorphins, dopamine, thyrotropin-releasing hormones, and growth hormone-releasing hormones as well as glial cells (Brown, 1998). Neurons were separated from glial cells by filtering mixed hypothalamic cells through a 48-µM nylon mesh. Hypothalamic cells were then sedimented at 400 g for 10 min; pellets were resuspended in HEPES-buffered Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (HDMEM, 4.5 g/l glucose; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and cells were cultured into 25-cm2 polyornithine coated tissue culture flasks (2.5 million cells/flask) in HDMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. On day 2, the culture medium was replaced with HDMEM containing 10% FBS, 33.6 µg/ml uridine, and 13.6 mg/ml 5-fluodeoxyuridine to prevent the overgrowth of astroglial cells. These chemicals were obtained from Sigma. On day 3, the culture medium was replaced with HDMEM containing serum supplement (SS; 30 nM selenium, 20 nM progesterone, 1 mM iron-free human transferrin, 5 mM insulin, and 100 mM putrescin) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were maintained for the next two days with this medium. By this time, the cultures were approximately 85 – 90% neurons, as determined by microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) positivity (Sarkar et al., 2008).

MBH neuronal cells were isolated and cultured in T25 flasks (1×106/well) for 2 days prior to experimentation. These cultures were used to determine the effect of ethanol-activated microglia on neuronal cell death by exposing the neuronal cells for 24 h with vehicle or conditioned medium from microglia (1×105) cultures treated for 24 h with no ethanol (CM), 50 mM ethanol (E1), or 100 mM (E2). We have previously characterized the basal apoptotic death rate of MBH neurons in primary cultures (Chen et al., 2006; De et al., 1994). The data of these studies revealed that apoptotic cell death remains constant between day 3 and 7 in MBH cell cultures. Cell lysates were used to determine apoptotic death using a nucleosome ELISA. The effects of various cytokines on neuronal cell death were determined by treating these cells (1×106/flask) with various doses of TNF-α (5 or 50 ng/ml; this concentrations range is similar to the amount microglia cells secrete this cytokine in culture), IL-1β or IL-6 (0.1 or 1 ng/ml; this concentrations range is similar to the amount microglia cells secrete these cytokines in culture) for a period of 24 h. Cytokines were purchased from R&D System (Minneapolis, MN). Cell lysates were used to determine apoptotic cell death. In the experiments where the role of TNF-α is determined, fetal MBH neuronal cells were exposed to conditioned medium from microglia (1×105) cultures treated for 24 h with 50 mM ethanol (E-CM) or no ethanol (CM). A dose of 10 µg/ml antibody to TNF-α (R&D System; effective doses recommended by the company) was then added to E-CM (E-CM + ab-TNF-α) or CM (CM + ab-TNF-α), mixed and added to neuron cultures to determine neuronal apoptosis. The effect of dbcAMP, on the ability of ethanol-activated microglia conditioned media to induce apoptosis of MBH neurons was determined by exposing neuronal cells for a 24 h period with conditioned medium of microglial cells (1×105) treated for 24 h with a 50 mM dose of ethanol without or with a 1µM/ml dose of dbcAMP, or with a 1µM/ml dose of dbcAMP alone. This dose of dbcAMP has been shown to be effective in preventing apoptotic death in MBH cells (Chen et al., 2006). Control cultures were treated with vehicle only. Cell lysates were used to determine apoptotic death using a nucleosome ELISA.

Microglial cultures

Microglia cells were prepared from the cerebral cortex of the same fetal rats used for MBH neuronal cultures using a method described previously (McCarthy and de Vellis, 1980). Cortices were dissociated by passing through a 70-µm Nitex mesh and plated at 2 × 105 cells/cm2. Cultures were fed every four days with DMEM/MEM/Hams 12 (DMEMF2) in a 4:5:1 ratio with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). On day 12, the culture was shaken on a rotary shaker at 800 rpm for 1 h (Frei et al, 1987). The suspended cells were plated on uncoated T25 flasks and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Then the medium containing suspended cells was discarded and adherent cells were fed with DMEMF12 for 3 days to develop the microglial culture prior to experimentation. To confirm the microglia positive cells, the culture was labeled with microglial marker (antibody Annexin 1) or the astrocyte marker glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). The cultures with positive cells for Annexin 1 were considered microglial cells. Microglial cells were isolated and cultured in DMEMF12 in 24 well plates (1×105) and treated for 24 h with 50 or 100 mM ethanol, or vehicle. A group of cultures was treated with 10 ng/ml lipopolysaccharide (LPS) as a positive control. The media samples were collected and used for the measurement of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, MIP-1α and MIP-2 by ELISA. In the experiment where the effects of dbcAMP on basal and ethanol-induced release of TNF-α were measured, microglial cells were isolated and cultured in DMEMF12 in 24 well plates (1×105) and treated for 24 h with a 50 mM dose of ethanol without or with a 1µM/ml dose of dbcAMP (cAMP), or with a 1µM/ml dose of cAMP alone for a period of 24 h. Control cultures were treated with vehicle only. The media samples were collected and used for the measurement of TNF-α by ELISA.

Cytokine measurements

The levels of TNF-α IL-1 β and IL-6 in the medium were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) methods using the procedures described in the kit (Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). The levels of rat MIP-1α and rat MIP-2 in the medium were determined by ELISA kit (BioSource International, Camarillo, California, USA).

Nucleosome ELISA Assay

In order to determine an apoptotic death of neurons, MBH cell extracts were used to measure levels of nucleosomes by nucleosome ELISA (Oncogene Research Products, Boston, MA) following instructions from the manufacturer. Protein contents of the cell extracts were determined using Bio-Rad DC Protein Assay reagents (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Immunohistochemistry

Cell cultures were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and then in 70% ethanol for an additional 30 min. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Primary antibodies used were a polyclonal antibody rabbit anti-Annexin 1 (1:500; Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisko, CA, USA), monoclonal antibodies anti-OX-6 (Bioproducts for Science, Inc., Indianapolis, IN; 1:200) and anti-GFAP (20 µg/ml; glial fibrillary acid protein, from BD Pharmingen, USA). The secondary antibody used to react with mouse primary antibodies was Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-mouse IgG, (4µg/ml; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and the secondary antibody used to react with rabbit primary antibody was Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (4µg/ml; Molecular Probes). Both of these secondary antibodies failed to stain cells in the absence of a primary antibody. Cell cultures were mounted using DAPI-containing Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories Inc. Burlingame, CA). Fluorescent images were captured with a Cool SNAP-pro CCD camera coupled to a Nikon-TE 2000 inverted microscope. Images were processed with Adobe Photoshop 7.0.

Statistical Analysis

The data shown in the figures and text are mean ± S.E.M. Data comparisons between two groups were made using t tests, whereas comparisons among multiple groups were made using one-way analysis of variance. Post hoc tests utilized the Student-Newman-Keuls test. A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

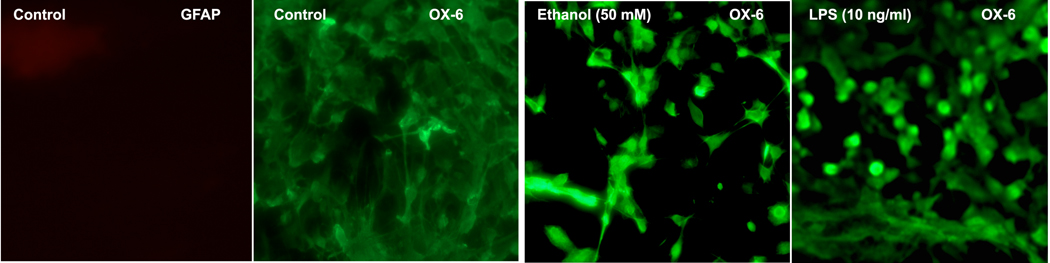

Ethanol activates microglia in primary cultures

To determine whether ethanol activates microglia in primary cultures, we used the OX-6 antibody-staining procedure (Bellucci et al., 2004). Since LPS is known to activate microglia (Sohn et al., 2007), we used this agent as a positive control. We also used GFAP staining to identify whether microglial cells were contaminated with astrocytes. We used two different concentrations of ethanol (50 and 100 mM) which are known to induce apoptotic death of MBH neurons (De et al., 1994). These doses of ethanol are equivalent to 0.23 g/dl and 0.46 g/dl. The treatment with ethanol or LPS increased the number of OX-6-immunostained cells (Fig. 1). The control microglia cells had minimum staining with OX-6.

Fig.1. The effect of ethanol on microglia activation: histochemical evidence.

Microglial cells were isolated and cultured on slide chambers for 3 days. The cells were then exposed to control media (CONT) or media containing ethanol 50 mM or LPS (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. Cells were then processed and stained for activated microglia marker (OX-6) or the astrocyte marker glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP).

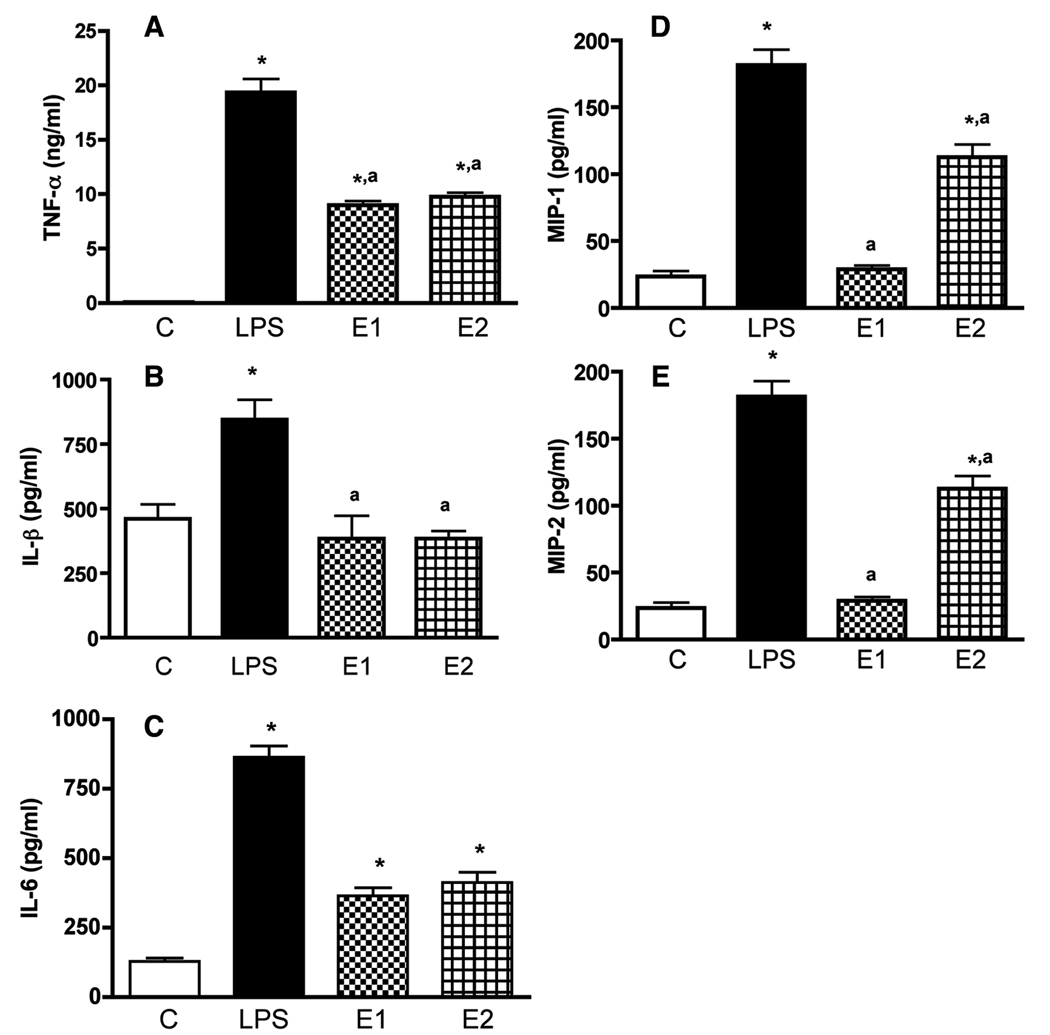

Ethanol increases the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, MIP-1α and MIP-2 in the media of cultured microglia

Microglial cells are known to produce many inflammatory cytokines (Henkel, 2009). We characterized the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, MIP-1α and MIP-2 in the media of microglial cell cultures after treatment with ethanol or LPS. The basal levels of most of the cytokines with exception of TNF-α were detectable in the media samples of microglial cultures (Fig. 2). As expected from previous studies the microglial activator LPS (Sohn et al., 2007), when added at a dose range of 10 ng/ml, was able to elevate the secretion of cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, MIP-1α and MIP-2) from microglial cells in cultures. Ethanol at a dose range of 50 and 100 mM significantly increased the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, MIP-1α and MIP-2, but failed to increase the level of IL-1β in media samples of microglia cultures.

Fig.2. The effect of ethanol and LPS on TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, MIP-1α and MIP-2 secretion from cultured microglia in primary cultures.

Microglial cells were isolated and cultured in 24 well plates (1×105) and treated for 24 h with 50 mM ethanol (E1) or 100 mM (E2). A group of cultures was treated with 10 ng/ml lipopolyssacaride (LPS) as a positive control. Control cultures were treated with vehicle only (C). The media samples were collected and used for the measurement of TNF-α (A), IL-1β (B), IL-6 (C), MIP-1α (D) and MIP-2 (E) by ELISA. Each bar represents mean ± SEM of 4–6 samples. *P< 0.001, as compared to C. aP< 0.001, as compared to LPS.

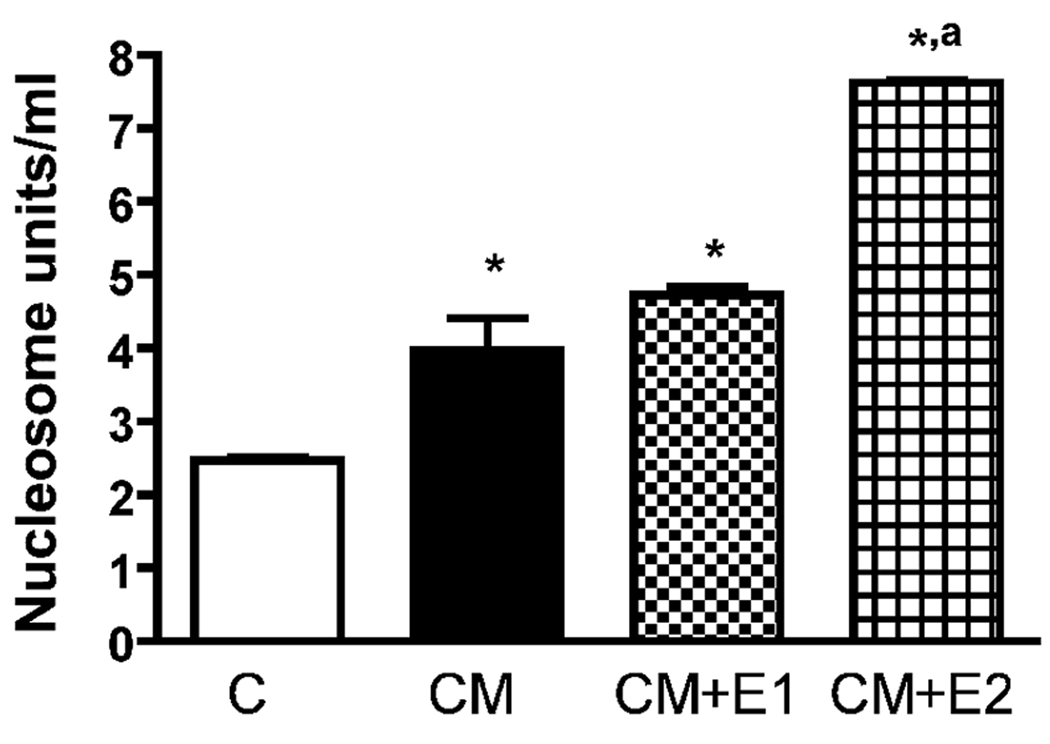

Ethanol-activated microglia-derived conditioned medium induces apoptosis of MBH neurons

Previously, we have shown that ethanol increases neuronal death in the primary cultures of MBH neurons (De et al., 1994; Sarkar et al., 2007). Whether microglial cells are involved in ethanol’s neurotoxic action on the hypothalamus was determined by measuring the ability of ethanol-activated microglia-derived conditioned media to induce apoptotic death in enriched MBH neurons. We determined the apoptotic death of neurons by measuring the nucleosome activity (a marker for DNA damage in the cells; Allen et al., 1997). We have previously used nucleosome ELISA to determine the apoptotic cell death induced by ethanol in MBH cells cultures (Chen et al., 2005). In our earlier study, we have shown that the data obtained by nucleosome ELISA correlate well with the data obtained from assays of other apoptotic cell death markers (Tunnel and caspase-3). As shown in Fig. 3, ethanol’s ability to induce apoptotic death, as determined by the amount of nucleosome present in neuronal cells, is increased when these neuronal cells were maintained in the presence of conditioned media from microglial cells.

Fig.3. The effect of ethanol-activated microglia conditioned media on an apoptotic cell death of fetal MBH neurons.

Fetal MBH neuronal cells were isolated and cultured in T25 flasks (1×106/well) for 2 days. The cells were then exposed for 24 h with vehicle (C) or conditioned medium from microglia cultures (1×105 cells) treated for 24 h with no ethanol (CM), 50 mM ethanol (CM + E1), or 100 mM (CM + E2). The neuron culture cell lysates were used to determine apoptotic death using a nucleosome ELISA. Each bar represents mean ± SEM of 5–6 samples. *P< 0.001, as compared to C. aP< 0.001, as compared to CM.

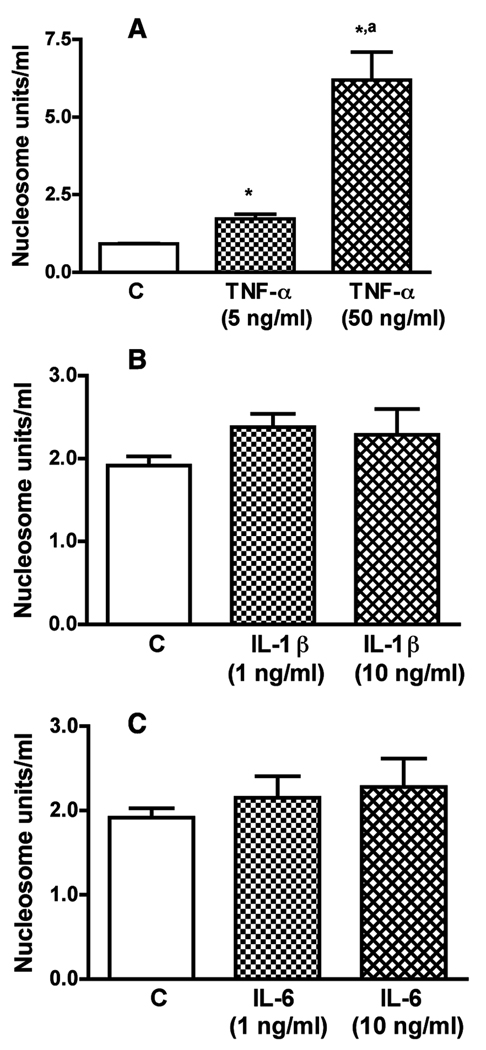

Cytokine TNF-α but not IL-1β or IL-6, increases apoptotic death of MBH neurons

In order to evaluate the role microglia-derived cytokines in ethanol’s neurotoxic action on MBH neurons, we first determined the effect of TNF-α, IL-1β or IL-6 on nucleosome activity (a marker for DNA damage in the cells; Allen et al., 1997) in enriched MBH neurons in primary cultures. In order to determine the physiological effect of these cytokines, we applied the doses similar to the concentrations of cytokines produced in the media of microglial cells with and without ethanol (shown in Fig. 2). Incubation of MBH neurons with various doses of TNF-α increased nucleosome activity (Fig. 4A). However, treatments with various doses of IL-1β or IL-6 produced minimal effects on the nucleosome activity in MBH neurons in cultures. These data suggest that TNF-α is a strong candidate to be the microglia-derived cytokine that induces apoptotic cell death of MBH neurons.

Fig.4. Effects of TNF-α IL-1β and IL-6 on apoptosis of MBH neurons.

Fetal MBH neuronal cells were isolated and cultured in T25 flasks (1×106/well) for 2 days. The cells were then exposed for 24 h with various doses of TNF-α (A), IL-1β (B) or IL-6 (C) for a period of 24 h. Cell lysates were used to determine apoptotic death using a nucleosome ELISA. Each bar represents mean ± SEM of 5–6 simples. *P< 0.001, as compared to C. aP< 0.001, as compared to TNF-α (5 ng/ml).

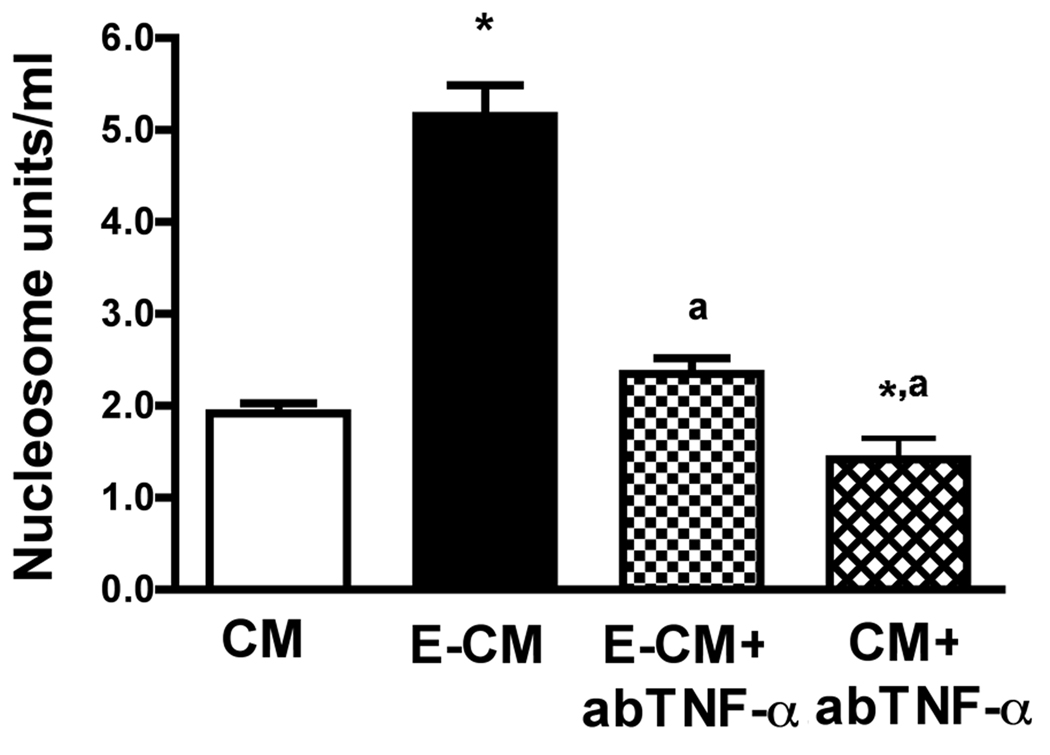

Immunoneutralization of TNF-α reduces the ability of ethanol-activated microglia conditioned media to induce apoptotic death of MBH neurons

Since TNF-α showed a significant apoptotic action on enriched MBH neurons, we evaluated whether the microglia-derived TNF-α has a mediatory role in ethanol’s apoptotic action on MBH neurons. The conditioned medium of an ethanol-treated microglia culture (CM) was first treated with TNF-α antibody or immunoglobulin, and then the ability of immunoneutralized and control CM to induce apoptosis of MBH neurons was compared. The data shown in Fig. 5 indicates that immunoneutralization of TNF-α significantly suppressed the CM’s ability to induce apoptosis in MBH neurons. These data support a mediatory role of microglia-derived TNF-α in an apoptotic effect of ethanol on MBH neurons.

Fig.5. The effect of immunoneutralization of TNF-α on the ability of ethanol-activated microglia conditioned media to induce apoptosis of MBH neurons.

Fetal MBH neuronal cells were isolated and cultured in T25 flasks (1×106/well) for 2 days. The cells were then exposed to conditioned medium from microglia treated for 24 h with 50 mM ethanol (E-CM) or no ethanol (CM). A dose of 10 µg/ml antibody to TNF-α was then added to E-CM (E-CM + ab-TNF-α) or CM (CM + ab-TNF-α) mixed and added to neuron cultures to determine neuronal apoptosis by nucleosome ELISA. Each bar represents mean ± SEM of 5–6 samples. *P< 0.001, as compared to CM. aP< 0.001, as compared to E-CM.

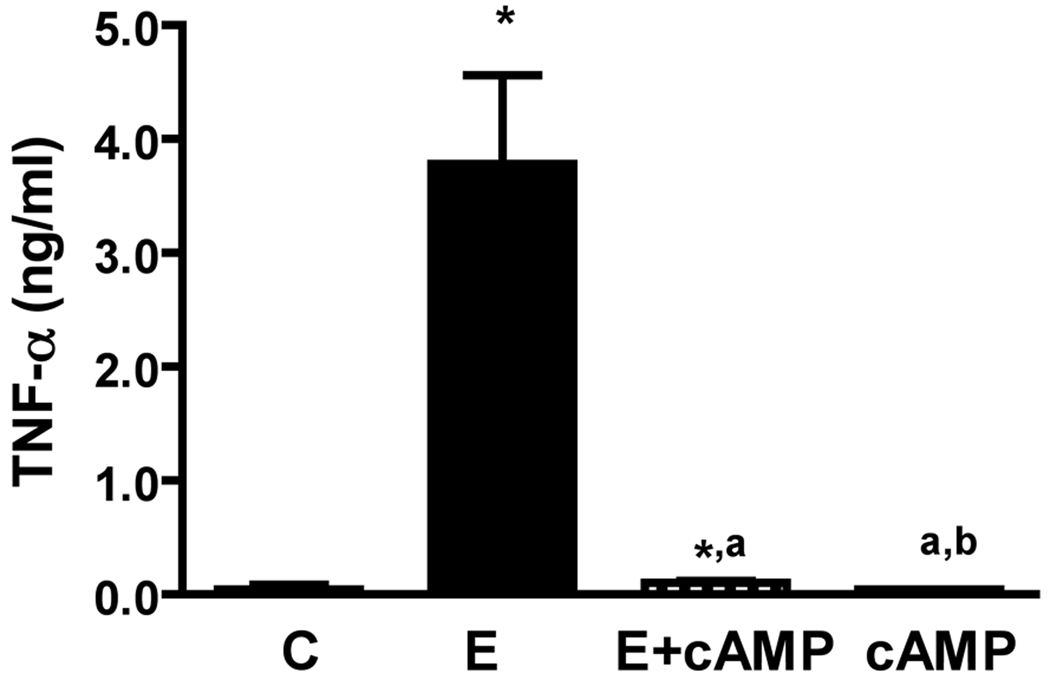

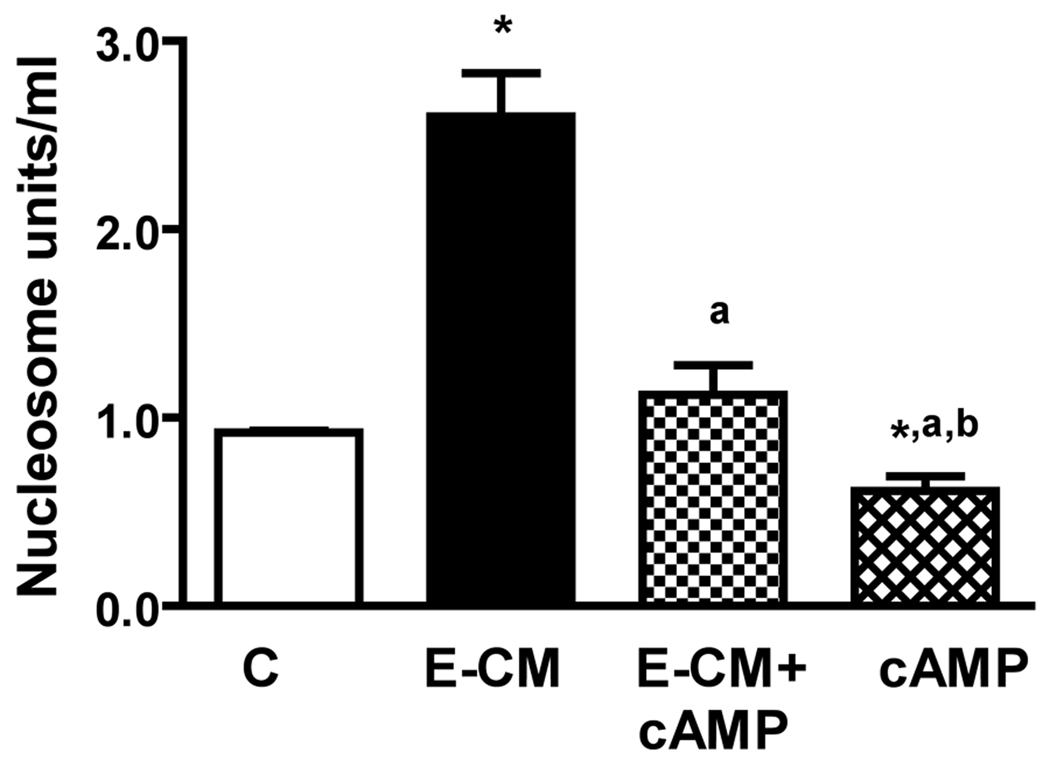

cAMP decreases the secretion of TNF-a from microglia and reduces the ability of ethanol-activated microglia conditioned media to induce apoptotic death of MBH neurons

We have observed previously that cAMP inhibits an apoptotic effect of ethanol on MBH neurons (Chen et al., 2006; De et al., 1994). To establish whether the neuroprotective action of cAMP involves suppression of TNF-α production from microglia, we determined the effects of cAMP on the basal and ethanol-induced release of TNF-α from cultured microglia. Then, we evaluated the effects cAMP has to alter the ability of ethanol-activated CM in inducing apoptosis in MBH neurons. Fig.6 shows that cAMP significantly reduced the basal and ethanol-induced levels of TNF-α in medium of cultured microglia. The neuroprotective agent also reduced the basal level and the ethanol-activated microglia CM-induced nucleosome activity in MBH neurons in cultures (Fig. 7). These results suggest that cAMP decreases the ethanol’s apoptotic effects on MBH neurons, at least partly, via inhibiting the TNF-α release from microglia.

Fig.6. Effects of dbcAMP on basal and ethanol-induced release of TNF-α from microglial cells.

Microglial cells were isolated and cultured in 24 well plates (1×105) and treated for 24 h with a 50 mM dose of ethanol without (E) or with a 1µM/ml dose of dbcAMP (E + cAMP), or with a 1µM/ml dose of dbcAMP alone (cAMP) for a period of 24 h. Control cultures were treated with vehicle only (C). The media samples were collected and used for the measurement of TNF-α by ELISA. Each bar represents mean ± SEM of 5–6 samples. *P< 0.001, as compared to C. aP< 0.001, as compared to E-CM. bP< 0.001, as compared to E-CM + cAMP.

Fig.7. Effects of dbcAMP on the ability of ethanol-activated microglia conditioned media to induce apoptosis of MBH neurons.

Microglial cells were isolated and cultured in 24 well plates (1×105) and treated for 24 h with a 50 mM dose of ethanol without (E) or with a 1µM/ml dose of dbcAMP (E + cAMP), or with a 1µM/ml dose of dbcAMP alone (cAMP) for a period of 24 h. Control cultures were treated with vehicle only (C). Cell lysates were used to determine apoptotic death using a nucleosome ELISA. Each bar represents mean ± SEM of 5–6 samples. *P< 0.01, as compared to C. aP< 0.001, as compared to E-CM. bP< 0.001, as compared to E-CM+cAMP.

DISCUSSION

The data presented here provide evidence that ethanol increases microglial activity and elevates secretion of cytokines TNF-α IL-6, MIP-1 and MIP-2 from microglial cells in primary cultures. Of these cytokines, TNF-α increases apoptotic action of ethanol on fetal MBH neurons. Immunoneutralization of TNF-α reduces the ability of ethanol-activated microglia to induce apoptotic death of MBH neurons. Additionally, the data show that the anti-apoptotic agent dbcAMP inhibits the secretion of TNF-α from microglia cells and suppresses the ability of ethanol’s activated microglia to cause apoptotosis of MBH neurons. Taken together, our results demonstrate that chronic ethanol treatments activate microglial cells and stimulate the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α which participates in mediation of ethanol’s apoptotic action on enriched MBH neurons in primary cultures.

Microglial cells are involved in the control of neuronal activities both in the adult and in the developing brain (Carnevale et al., 2007). Our data indicate that the ethanol treatment paradigm that induces apoptotic death of fetal MBH neurons increases the number of OX-6 stained microglia in a culture model of fetal brain. We also showed that ethanol increased the level of chemokines macrophage inflammatory proteins, MIP-1 α and MIP-2. These data suggest that in primary cultures of cortical microglia ethanol activates microglia. Previously, it has been shown that there is significant activation and hypertrophy of microglia in the spinal cord during ethanol-dependent neuropathic pain-like states (Narita et al., 2007). Using a positron emission tomography (PET) technique, it was recently shown that ethanol injury in the rat striatum was associated with an increased number of activated microglia at the site of injury in live animals (Toyama et al., 2008). The PET data was confirmed with histochemical data in the postmortem brains of these animals. Similarly, by employing autoradiographic analysis, it has been shown that intrastriatal injection of ethanol increases the number of microglia at the site of injury (Maeda et al., 2007). Fernandez et al have recently shown an increase in the number of CD11b immunoreactive microglia in cerebral cortex sections of mice treated with one i.p. injection of ethanol (4 g/kg) for 3 consecutive days (Fernandez-Lizarbe et al., 2009). Additionally, Watari et al have identified the foci of significant fetal white matter microglia-macrophage immunoreactivity in a "binge" model of early prenatal alcohol exposure in sheep. (Watari et al., 2006). An increase in microglial markers was also observed in adult brain regions in human alcoholics (He and Crews, 2008). These data suggest that, like in vivo, the cultured microglia of fetal brain respond similarly to a ethanol challenge.

Characterization of the cytokines secreted from fetal microglia in cultures revealed that ethanol was able to increase in a dose-dependent manner the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β. These data are in agreement with the data showing that in adult mice chronic ethanol administration increases TNF-α levels in the brain and liver, and increases the LPS-induced increase in IL-1β level in the brain and other tissues (Quin et al., 2008). Our in vitro data is also in agreement with the data showing that ethanol treatment increases pro-inflammatory cytokines in the hypothalamus of adult rats (Emanuele et al., 2005). In our study, we found only TNF-α, but not IL-1β and IL-6, was able to increase nucleosome activity in enriched MBH neurons. Although, both IL-1β and IL-6 have been shown to be able to cause neuronal death in many systems (Chiarini et al., 2006; Ozaktay et al., 2002), IL-1β was ineffective in inducing cell death in cultured cortical neurons (Soiampornkul et al., 2008), and IL-6 produced no effect on the level of survival of motor neurons (Streit et al., 2000). Microglia are considered a major producer of TNF-α, a cytokine that modulates cellular homeostasis in several tissues and modifies cell proliferation, differentiation, and death (Leong and Karsan, 2000). Using a mice model to induce selective death by apoptosis of dentate granule cells, Harry et al. (2002) were able to demonstrate that the neuronal damage was decreased with cerebroventricular injection of TNF-α antibody. These data are in agreement with our view that microglia-derived TNF-α may be involved in mediation of ethanol’s apoptotic action on neurons.

Previously, it has been shown that cAMP prevents ethanol-induced apoptosis of MBH neurons (De et al., 1994). Here, we provide evidence that cAMP decreased an apoptotic cell death of enriched developing neurons by modulating the effects of microglia conditioned medium on cultured neurons. Moreover, cAMP blocked microglia production of TNF-α. These data are in agreement with the finding that cAMP down-regulates the proinflammatory and neurotoxic cytokines from microglial cells (Suzumura et al., 1999). Recognizing the limitation of the in vitro study, the data presented here support the possibility that a decrease in production of cAMP in neurons and/or microglia following ethanol challenges increases the secretion of TNF-α from microglia that may lead to the demise of neurons in the hypothalamus of fetal brain.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Health Grant R37 AA08757.

REFERENCES

- Allen RT, Hunter WJ, III, Agrawal WJDK. Morphological and biological characterization and analysis of apoptosis. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 1997;37:215–228. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8719(97)00033-6. 3rd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellucci A, Westwood AJ, Ingram E, Casamenti F, Goedert M, Spillantini MG. Induction of inflammatory mediators and microglial activation in mice transgenic for mutant human P301S tau protein. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1643–1652. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63421-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyadjieva N, Sarkar DK. Effects of ethanol on basal and prostaglandin E1-induced increases in beta-endorphin release and intracellular cAMP levels in hypothalamic cells. Alcoholism: Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:1005–1009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyadjieva N, Sarkar DK. Effects of ethanol on basal and adenosine-induced increases in beta-endorphin release and intracellular cAMP levels in hypothalamic cells. Brain Res. 1999;824:112–118. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RE. An Introduction to Neuroendocrinology. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1998. pp. 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce-Keller AJ. Microglial-neuronal interactions in synaptic damage and recovery. J Neurosci Res. 1999;58:191–201. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4547(19991001)58:1<191::aid-jnr17>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale D, De Simone R, Minghetti L. Microglia-neuron interaction in inflammatory and degenerative diseases: role of cholinergic and noradrenergic systems. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2007;6:388–397. doi: 10.2174/187152707783399193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CP, Kuhn P, Chaturvedi K, Boyadjieva NI, Sarkar DK. Ethanol induces apoptotic death of developing b-endorphin neurons via suppression of cyclic adenosin monophosphate production and activation of transforming growth actor--β1-linked apoptotic signaling. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:706–717. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.017004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarini A, Dal Pra I, Whitfield JF, Armato U. The killing of neurons by beta-amyloid peptides, prions, and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Ital J Anat Embryol. 2006;111:221–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews F, Nixon K, Kim D, Joseph J, Shukitt-Hale B, Qin L, Zou J. BHT blocks NF-kappaB activation and ethanol-induced brain damage. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1938–1949. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Nixon K. Mechanisms of neurodegeneration and regeneration in alcoholism. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44:115–127. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De A, Boyadjieva N, Pastoric M, Reddy BV, Sarkar DK. cAMP and ethanol interact to control apoptosis and differentiation in hypothalamic beta-endorphin neurons. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26697–26705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuele N, LaPaglia N, Kovacs EJ, Emanuele MA. Effects of chronic ethanol (EtOH) administration on pro-inflammatory cytokines of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis in female rats. Endocr Res. 2005;31:9–16. doi: 10.1080/07435800500228930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Lizarbe S, Pascual M, Guerri C. Critical role of TLR4 response in the activation of microglia induced by ethanol. J Immunol. 2009;183:4733–4744. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hack SP, Christie MJ. Adaptations in adenosine signaling in drug dependence: therapeutic implications. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 2003;15:235–274. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v15.i34.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harry GJ, Lefebvre d'Hellencourt C, McPherson CA, Funk JA, Aoyama M, Wine RN. Tumor necrosis factor p55 and p75 receptors are involved in chemical-induced apoptosis of dentate granule neurons. J Neurochem. 2008;106:281–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Crews FT. Increased MCP-1 and microglia in various regions of the human alcoholic brain. Exp Neurol. 2008;210:349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellemans KG, Verma P, Yoon E, Yu W, Weinberg J. Prenatal alcohol exposure increases vulnerability to stress and anxiety-like disorders in adulthood. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1144:154–175. doi: 10.1196/annals.1418.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkel JS, Beers DR, Zhao W, Appel SH. Microglia in ALS: The Good, The Bad, and The Resting. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2009;4:389–398. doi: 10.1007/s11481-009-9171-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JS, Miller MW. Proliferation and death of cultured fetal neocortical neurons: effects of ethanol on the dynamics of cell growth. J Neurocytol. 2001;30:391–401. doi: 10.1023/a:1015013609424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Jeong J, Son E, Mosa A, Cho GJ, Choi WS, Ha JH, Kim JK, Lee MG, Kim CY, Suk K. Ethanol selectively modulates inflammatory activation signaling of brain microglia. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;156:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong KG, Karsa A. Signaling pathways mediated by tumor necrosis factor alpha. Histol Histopathol. 2000;15:1303–1325. doi: 10.14670/HH-15.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light KE, Belcher SM, Pierce DR. Time course and manner of Purkinje neuron death following a single ethanol exposure on postnatal day 4 in the developing rat. Neuroscience. 2002;114:327–337. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00344-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda J, Higuchi M, Inaji M, Ji B, Haneda E, Okauchi T, Zhang MR, Suzuki K, Suhara T. Phase-dependent roles of reactive microglia and astrocytes in nervous system injury as delineated by imaging of peripheral benzodiazepine receptor. Brain Res. 2007;1157:100–111. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier SE, Cramer JA, West JR, Sohrabji F. Alcohol exposure during the first two trimesters equivalent alters granule cell number and neurotrophin expression in the developing rat olfactory bulb. J Neurobiol. 1999;41:414–423. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19991115)41:3<414::aid-neu9>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy KD, de Vellis J. Preparation of separate astroglial and oligodendroglial cell cultures from rat cerebral tissue. J Cell Biol. 1980;85:890–902. doi: 10.1083/jcb.85.3.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW. Generation of neurons in the rat dentate gyrus and hippocampus: effects of prenatal and postnatal treatment with ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:1500–1509. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monier A, Adle-Biassette H, Delezoide AL, Evrard P, Gressens P, Verney C. Entry and distribution of microglial cells in human embryonic and fetal cerebral cortex. J Neuropathol Exp. 2007;66:372–382. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e3180517b46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulder KL, Fu T, Melbostad H, Cormier RJ, Isenberg KE, Zorumski CF, Mennerick S. Ethanol-induced death of postnatal hippocampal neurons. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;20:396–409. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M, Miyoshi K, Narita M, Suzuki T. Involvement of microglia in the ethanol-induced neuropathic pain-like state in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 2007;414:21–25. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaktay AC, Cavanaugh JM, Asik I, DeLeo JA, Weinstein JN. Dorsal root sensitivity to interleukin-1 beta, interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor in rats. Eur Spine J. 2002;11:467–475. doi: 10.1007/s00586-002-0430-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez G, Rey S, von Bernhardi R. Proinflammatory stimuli are needed for induction of microglial cell-mediated AbetaPP {244-C} and Abeta-neurotoxicity in hippocampal cultures. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;15:45–59. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-15104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaie P, Trillo-Pazos G, Greenwood J, Everall IP, Male DK. Motility and ramification of human fetal microglia in culture: an investigation using time-lapse video microscopy and image analysis. Exp Cell Res. 2002;274:68–82. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riikonen J, Jaatinen P, Rintala J, Porsti I, Karjala K, Hervonen A. Intermittent ethanol exposure increases the number of cerebellar microglia. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37:421–426. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.5.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar DK, Kuhn P, Marano J, Chen C, Boyadjieva N. Alcohol exposure during the developmental period induces beta-endorphin neuronal death and causes alteration in the opioid control of stress axis function. Endocrinology. 2007;148:2828–2834. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar DK, Boyadjieva NI, Chen CP, Ortigüela M, Reuhl K, Clement KM, Kuhn P, Marano J. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate differentiated beta-endorphin neurons promote immune function and prevent prostate cancer growth. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9105–9110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800289105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn MJ, Noh HJ, Yoo ID, Kim WG. Protective effect of radicicol against LPS/IFN-gamma-induced neuronal cell death in rat cortical neuron-glia cultures. Life Sci. 2007;80:1706–1712. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soiampornkul R, Tong L, Thangnipon W, Balazs R, Cotman CW. Interleukin-1beta interferes with signal transduction induced by neurotrophin-3 in cortical neurons. Brain Res. 2008;1188:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit WJ, Hurley SD, McGraw TS, Semple-Rowland SL. Comparative evaluation of cytokine profiles and reactive gliosis supports a critical role for interleukin-6 in neuron-glia signaling during regeneration. J Neurosci Res. 2000;61:10–20. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000701)61:1<10::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suk K. Microglial signal transduction as a target of alcohol action in the brain. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2007;4:131–142. doi: 10.2174/156720207780637261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzumura A, Ito A, Yoshikawa M, Sawada MI. Ibudilast suppresses TNFalpha production by glial cells functioning mainly as type III phosphodiesterase inhibitor in the CNS. Brain Res. 1999;837:203–212. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01666-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas WE. Characterization of the dynamic nature of microglial cells. Brain Res Bull. 1990;25:351–354. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(90)90083-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyama H, Hatano K, Suzuki H, Ichise M, Momosaki S, Kudo G, Ito F, Kato T, Yamaguchi H, Katada K, Sawada M, Ito K. In vivo imaging of microglial activation using a peripheral benzodiazepine receptor ligand: [11C]PK-11195 and animal PET following ethanol injury in rat striatum. Ann Nucl Med. 2008;22:417–424. doi: 10.1007/s12149-008-0136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watari H, Born DE, Gleason CA. Effects of first trimester binge alcohol exposure on developing white matter in fetal sheep. Pediatr Res. 2006;59:560–564. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000203102.01364.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelivyanskaya ML, Nelson JA, Poluektova L, Uberti M, Mellon M, Gendelman HE, Boska MD. Tracking superparamagnetic iron oxide labeled monocytes in brain by high-field magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosci Res. 2003;73:284–295. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]