Abstract

A 51-year-old Chinese male with a 20-year history of hepatitis B was diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma in the right anterior portion of the liver, sized 3.5 cm × 3.2 cm, and was treated with radiofrequency ablation (RFA) on December 18, 2001. The patient did not receive antiviral therapy for hepatitis B virus after RFA. The treated lesion reduced gradually and reached its minimum size of 1.7 cm × 1.5 cm seven years later on November 18, 2008. However computed tomography findings revealed that a recurrence lesion of 6.0 cm × 4.8 cm which was histologically confirmed overlapped the previous treated lesion at the 8th year on December 3, 2009. Although recurrence at 8 years after curative RFA is a rare event, such a possibility must be kept in mind. To find and treat the recurrence lesion promptly, long-term and close monitoring is warranted after RFA. Meanwhile, the recurrence-prevention therapy is as important as close monitoring for those patients with a history of hepatitis B.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Radiofrequency ablation, Recurrence

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a worldwide health problem and a poor prognostic disease. Local treatments are the main approach for early HCC. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is a potentially curative therapy for early HCC. Emerging clinical evidence has demonstrated that RFA can obtain the same survival rate as surgical resection[1-3]. However, follow-up after RFA is not yet adequately addressed by international guidelines. How long and how often should the follow-up be taken remains unclear. Here, we report a rare case of HCC locally recurring 8 years after RFA and review the literature.

CASE REPORT

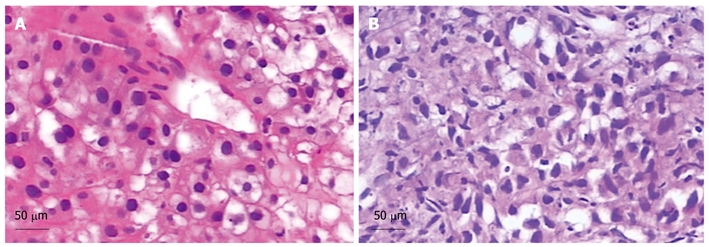

A 51-year-old Chinese male with a 20-year history of hepatitis B was diagnosed with HCC in his annual checkup. Spiral computed tomography (CT) revealed a 3.5 cm × 3.2 cm mass in the right anterior portion of the liver (Figure 1A). Liver biopsy was performed and the diagnosis of well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma was histologically confirmed (Figure 2A). Laboratory findings revealed the following: platelets: 207 000/mm3 [normal value: (100-300) × 103/mm3]; Prothrombin time: 13.9 s (normal values: 10.0-13.0 s); Activated partial thromboplastin time -26.8 s (normal values: 23.0-36.0 s); Total bilirubin: 11.3 μmol/L (normal values: 5.1-17.1 μmol/L); Direct bilirubin: 6.5 μmol/L (normal values: 0-6.0 μmol/L); Serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP): 5.6 μg/L (normal values: 0-8.1 μg/L); Albumin: 33.5 g/L (normal values: 35.0-55.0 g/L). HBsAg (+), HBsAb (-), HBeAg (+), HBeAb (-), HBcAb (+); Hepatitis B Virus (HBV)-DNA: 3.28 × 105 copies/mL; Hepatic function: Child-Pugh A.

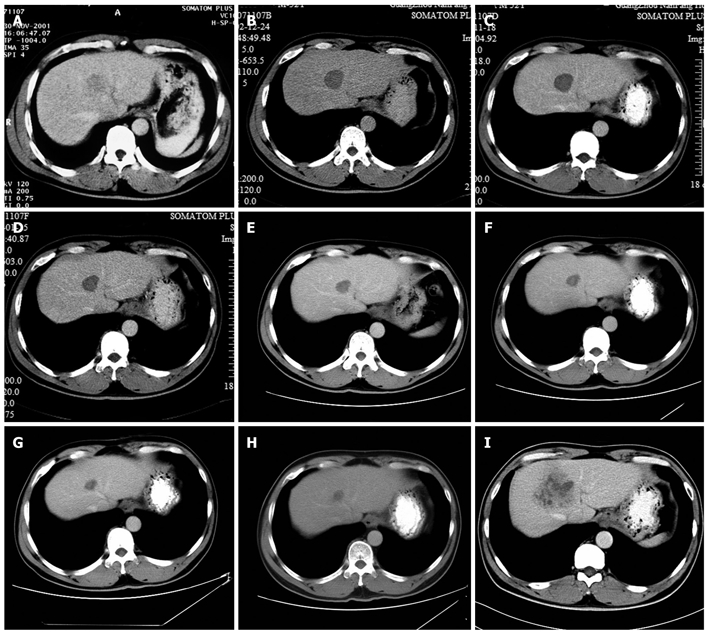

Figure 1.

Computed tomography images of the hepatocellular carcinoma. A: Tumor size was 3.5 cm × 3.2 cm before radiofrequency ablation (RFA) (2001-11); B: Tumor size was 3.2 cm × 3.1 cm at 12 mo after RFA (2002-12); C: Tumor size was 3.1 cm × 3.0 cm at 2 years after RFA (2003-11); D: Tumor size was 2.8 cm × 2.5 cm at 3 years after RFA (2005-1); E: Tumor size was 2.4 cm × 2.2 cm at 4 years after RFA (2005-11); F: Tumor size was 2.1 cm × 2.0 cm at 5 years after RFA (2006-09); G: Tumor size was 1.9 cm × 1.6 cm at 6 years after RFA (2007-11); H: Tumor size was 1.7 cm × 1.5 cm at 7 years after RFA (2008-11); I: Tumor size was 6.0 cm × 4.8 cm at 8 years after RFA (2009-12).

Figure 2.

Pathological examinations (HE stain). A: A well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Scale bar = 50 μm; B: A well-moderately differentiated HCC. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Following written informed consent, RFA was performed on December 18, 2001. Local anesthesia and conscious sedation were achieved with subcutaneous 1% lidocaine and intravenous midazolam and fentanyl. The RF delivery system was an RF 2000 generator system (Radio Therapeutics, USA), used in conjunction with a LeVeen needle electrode and two large grounding pads placed on the patient’s thighs. The RF generator supplies voltage at a frequency of 460 KHz and a maximum power output of 90 W. The active expandable needle electrodes have a 15 cm long stainless steel insulated cannula with 10 retractable lateral hooks. The maximum deployment diameter of the hooks was 3.5 cm. Using a multi-frequency convex probe, RFA was performed with real-time ultrasound guidance. The needle was inserted via the intercostal approach according to the ultrasonographic picture. When the end of the needle electrode was located in the center of the lesion, the hooks were deployed and the RF generator was activated. After maintaining a baseline power output at 50 W for 1 min, the output was increased by 10 W/min until it reached 90 W. Then the power output was kept at 90 W until radiofrequency generator system roll-off automatically[4].

No severe complication was observed after RFA procedure. One year after RFA, CT findings demonstrated the treated lesion as a low-attenuation area measuring 3.8 cm × 3.5 cm on December 24, 2002, with no contrast enhancement, overlapping the previous enhancing lesion (Figure 1B). No antiviral therapy for hepatitis B virus (HBV) was given after RFA.

The patient was regularly followed up at oncology outpatient department by performing examinations of abdominal ultrasound (US), contrast-enhanced CT and AFP. US and AFP tests were taken every 3-6 mo for 2 years, then annually for the next 3 years. Contrast-enhanced CT of the liver was performed annually.

The annual CT scan revealed that the treated lesion reduced gradually from 3.8 cm × 3.5 cm, December 24, 2002 to 1.7 cm × 1.5 cm, November 18, 2008 (Figure 1B-H). Serum AFP levels were normal throughout the follow-up period. However, on December 3, 2009, CT findings demonstrated that a recurrence lesion of 6.0 cm × 4.8 cm overlapped the previous treated lesion (Figure 1I). Liver biopsy proved the diagnosis of well-moderately differentiated HCC (Figure 2B). Laboratory findings: HBsAg (+), HBsAb (-), HBeAg (+), HBeAb (-), HBcAb (+), HBV-DNA: 7.36 × 105 copies/mL.

DISCUSSION

HCC is the fifth most common cancer worldwide and is particularly prevalent in China where most HCC are associated with chronic HBV infection. Local treatments are the main therapeutic approach for early HCC. Surgical resection is considered as the only potentially curative therapies[5] and hepatic resection (HR) is generally considered as the first option for early HCC in most guidelines. However many patients can not undergo a surgical operation because of the limited inclusion criteria. Consequently, as a potentially curative nonsurgical therapy, RFA has been developed[6,7]. Nowadays, RFA is recommended by the guidelines established by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)[6], European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL)[8] and the Japanese “Evidence-based guidelines”[9] for HCC measuring 3 cm or smaller.

Accumulated clinical evidence indicates that the efficacy of RFA is equal to that of a surgical resection for early HCC[1,10]. Meanwhile, the efficacy of RFA is tumor-size dependent. The risk factors for tumor recurrence after RFA include tumor size, insufficient safety margin, multinodular tumor and tumor location[11]. Among these risk factors, tumor size > 2.3-3.0 cm is the main risk factor for local recurrence[12-15]. To reduce the risk of recurrence after RFA, it is important to choose the right case according to the status of the lesions. Moreover, tumor recurrence was associated with hepatitis virus infection. Generally, it is recognized that tumor factors were associated with early HCC recurrence (within two years of local treatment) while high viral loads and hepatic inflammatory activity were associated with late recurrence (> 2 years after local treatment)[16]. Therefore, in view of the relation of HCC recurrence and hepatitis virus infection, secondary prevention of HCC after curative RFA is another essential clinical issue. Antiviral therapy may block the procedure of multicentric carcinogenesis in which new lesions are formed as a result of underlying hepatitis[17]. Lamivudine is a popular choice for the secondary prevention of recurrence after local treatment for HCC in chronic hepatitis B patients. A multicenter randomized controlled trial showed that lamivudine can reduce HCC incidence by approximately 50% in patients with chronic hepatitis B cirrhosis[18]. Lamivudine is also beneficial for preventing HCC in patients without cirrhosis[19]. Though its effect on survival of patients with HCC is to be proven, lamivudine after RFA for hepatitis B-related HCC was safe[20].

In this case, though no sufficient safety margin was obtained, CT findings showed that the lesion was completely necrotic one year after RFA and the treated lesion reduced gradually over the next seven years. It reduced to its minimum size of 1.7 cm × 1.5 cm on November 18, 2008. On December 3, 2009, CT image showed a 6.0 cm × 4.8 cm recurrence lesion, which was histologically confirmed. The lesion overlapped the previously treated one. The growth process of the recurrence lesion between November 18, 2008 and December 3, 2009 remains unknown because of the lack of imaging examination. Based on previous studies, multicentric carcinogenesis relating to hepatic inflammatory activity resulting from HBV infection is the most likely reason for recurrence in this case. We suppose that the recurrence lesion was very close to the previous treated one at the beginning and, as the accretion of the recurrence tumor, overlapped the previous treated lesion. Long-term survival without safety margins in this case may contribute to clinicopathological factors such as normal AFP and well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma. This case reminds us that after RFA, antiviral therapy should be given to patients with hepatitis B in order to reduce the recurrence rate of HCC. Both high-level and low-level viremia are associated with significant risk for HCC[21]. At the moment, evidence shows that antiviral therapy can lower the incidence of HCC in patients with viral hepatitis and that the therapy is rather safe[11,19,20]. Post-operative antiviral therapy may be crucial in reducing late recurrence[16]. The follow-up period after RFA should be extended. So far, it is reported that the longest time to recurrence occurred within 3 years of RFA[11]. Although rare, recurrence can occur 8 years later after RFA as with this case. Thus, a long-term follow-up is necessary. Intervals between follow-ups should be shortened. At present, local treatments work well in treating liver tumors smaller than 5 cm in diameter. In this case, the follow-up interval was set to be one year. When the recurrence was detected, the patient had missed the best chance of treatment due to the recurrence lesion being larger than 5 cm in diameter.

In conclusion, close monitoring and recurrence-prevention therapy after RFA is warranted.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Dr. Matthias Ocker, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine 1, University Hospital Erlangen, Ulmenweg 18, 91054 Erlangen, Germany

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Ma WH

References

- 1.Hiraoka A, Horiike N, Yamashita Y, Koizumi Y, Doi K, Yamamoto Y, Hasebe A, Ichikawa S, Yano M, Miyamoto Y, et al. Efficacy of radiofrequency ablation therapy compared to surgical resection in 164 patients in Japan with single hepatocellular carcinoma smaller than 3 cm, along with report of complications. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:2171–2174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hong SN, Lee SY, Choi MS, Lee JH, Koh KC, Paik SW, Yoo BC, Rhee JC, Choi D, Lim HK, et al. Comparing the outcomes of radiofrequency ablation and surgery in patients with a single small hepatocellular carcinoma and well-preserved hepatic function. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:247–252. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000152746.72149.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santambrogio R, Opocher E, Zuin M, Selmi C, Bertolini E, Costa M, Conti M, Montorsi M. Surgical resection versus laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and Child-Pugh class a liver cirrhosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3289–3298. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0678-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solmi L, Nigro G, Roda E. Therapeutic effectiveness of echo-guided percutaneous radiofrequency ablation therapy with a LeVeen needle electrode in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1098–1104. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i7.1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fong Y, Sun RL, Jarnagin W, Blumgart LH. An analysis of 412 cases of hepatocellular carcinoma at a Western center. Ann Surg. 1999;229:790–799; discussion 799-800. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199906000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42:1208–1236. doi: 10.1002/hep.20933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2003;362:1907–1917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14964-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruix J, Sherman M, Llovet JM, Beaugrand M, Lencioni R, Burroughs AK, Christensen E, Pagliaro L, Colombo M, Rodés J. Clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Conclusions of the Barcelona-2000 EASL conference. European Association for the Study of the Liver. J Hepatol. 2001;35:421–430. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Makuuchi M, Kokudo N, Arii S, Futagawa S, Kaneko S, Kawasaki S, Matsuyama Y, Okazaki M, Okita K, Omata M, et al. Development of evidence-based clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan. Hepatol Res. 2008;38:37–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogihara M, Wong LL, Machi J. Radiofrequency ablation versus surgical resection for single nodule hepatocellular carcinoma: long-term outcomes. HPB (Oxford) 2005;7:214–221. doi: 10.1080/13651820510028846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zytoon AA, Ishii H, Murakami K, El-Kholy MR, Furuse J, El-Dorry A, El-Malah A. Recurrence-free survival after radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma. A registry report of the impact of risk factors on outcome. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2007;37:658–672. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hym086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim YS, Rhim H, Cho OK, Koh BH, Kim Y. Intrahepatic recurrence after percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of the pattern and risk factors. Eur J Radiol. 2006;59:432–441. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikeda K, Seki T, Umehara H, Inokuchi R, Tamai T, Sakaida N, Uemura Y, Kamiyama Y, Okazaki K. Clinicopathologic study of small hepatocellular carcinoma with microscopic satellite nodules to determine the extent of tumor ablation by local therapy. Int J Oncol. 2007;31:485–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lam VW, Ng KK, Chok KS, Cheung TT, Yuen J, Tung H, Tso WK, Fan ST, Poon RT. Risk factors and prognostic factors of local recurrence after radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nouso K, Matsumoto E, Kobayashi Y, Nakamura S, Tanaka H, Osawa T, Ikeda H, Araki Y, Sakaguchi K, Shiratori Y. Risk factors for local and distant recurrence of hepatocellular carcinomas after local ablation therapies. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:453–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu JC, Huang YH, Chau GY, Su CW, Lai CR, Lee PC, Huo TI, Sheen IJ, Lee SD, Lui WY. Risk factors for early and late recurrence in hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2009;51:890–897. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishikawa T. Secondary prevention of recurrence by interferon therapy after ablation therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis C patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6140–6144. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, Farrell G, Lee CZ, Yuen H, Tanwandee T, Tao QM, Shue K, Keene ON, Dixon JS, Gray DF, Sabbat J. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1521–1531. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuen MF, Seto WK, Chow DH, Tsui K, Wong DK, Ngai VW, Wong BC, Fung J, Yuen JC, Lai CL. Long-term lamivudine therapy reduces the risk of long-term complications of chronic hepatitis B infection even in patients without advanced disease. Antivir Ther. 2007;12:1295–1303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshida H, Yoshida H, Goto E, Sato T, Ohki T, Masuzaki R, Tateishi R, Goto T, Shiina S, Kawabe T, et al. Safety and efficacy of lamivudine after radiofrequency ablation in patients with hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:89–94. doi: 10.1007/s12072-007-9020-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mendy ME, Welzel T, Lesi OA, Hainaut P, Hall AJ, Kuniholm MH, McConkey S, Goedert JJ, Kaye S, Rowland-Jones S, et al. Hepatitis B viral load and risk for liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in The Gambia, West Africa. J Viral Hepat. 2010;17:115–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01168.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]