Abstract

Optimal transplantation strategies are uncertain in primary hyperoxaluria (PH) due to potential for recurrent oxalosis. Outcomes of different transplantation approaches were compared using life table methods to determine kidney graft survival among 203 patients in the International Primary Hyperoxaluria Registry.

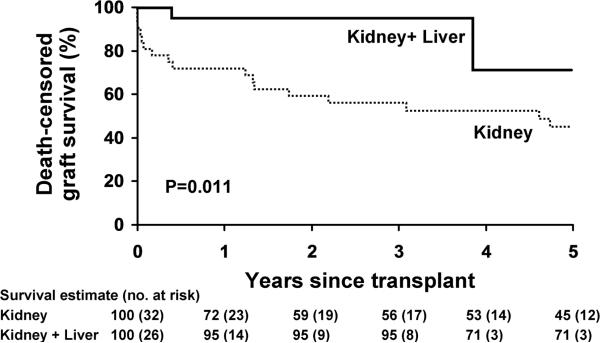

From 1976–2009, 84 kidney alone (K) and combined kidney and liver (K+L) transplants were performed in 58 patients. Among 58 first kidney transplants (32 K, 26 K+L), 1, 3, and 5 year kidney graft survival was 82%, 68%, and 49%. Renal graft loss occurred in 26 first transplants due to oxalosis in 10, chronic allograft nephropathy in 6, rejection in 5, and other causes in 5. Delay in PH diagnosis until after transplant favored early graft loss (p=0.07). K+L had better kidney graft outcomes than K with death censored graft survival 95% vs. 56% at 3yrs (p=.011). Among 29 year 2000–09 first transplants (24 K+L), 84% were functioning at 3 years compared to 55% of earlier transplants (p=0.05). At 6.8 years after transplantation, 46 of 58 patients are living (43 with functioning grafts).

Outcomes of transplantation in PH have improved over time, with recent K+L transplantation highly successful. Recurrent oxalosis accounted for a minority of kidney graft losses.

Keywords: Kidney transplantation, liver transplantation, oxalosis, primary hyperoxaluria

Introduction

Inherited deficiency of hepatic alanine:glyoxylate aminotransferase (AGT) in primary hyperoxaluria type 1 (PH1) or glyoxylate reductase/hydroxypyruvate reductase (GRHPR) in primary hyperoxaluria type 2 (PH2) results in marked overproduction of oxalate by the liver (1,2). Oxalate cannot be metabolized in the human body, thus the excess oxalate must be eliminated, largely by the kidneys, resulting in marked hyperoxaluria. High concentrations of oxalate in the urine form complexes and crystals with calcium resulting in urinary tract stones, as well as injury to renal tubule epithelial cells and nephrocalcinosis (3). Calcium oxalate crystals in the interstitium of the kidney induce injury characterized by recruitment of macrophages and release of inflammatory mediators, cellular infiltrates, granuloma formation, and scarring. Over time there is progressive loss of renal function (4–6). In PH1, the more severe form, median age at time of end stage kidney failure is 25–35 years (7–9), although it can occur as early as infancy (10). As renal function declines and renal excretion of oxalate is less efficient, the plasma concentration of oxalate begins to rise, eventually exceeding the saturation threshold in the blood. Systemic deposition of calcium oxalate crystals in many organs inevitably ensues. Consequences include fracturing bone disease, non-healing cutaneous ulcers, treatment refractory anemia, retinal calcium oxalate deposition, cardiomyopathy, and arrhythmias due to deposition in the cardiac conduction system (6). Even when intensive, dialysis removal of oxalate most often fails to keep up with daily hepatic production (11). Thus transplantation is required to prevent severe and progressive systemic oxalosis (6).

However, transplantation strategies are also challenging in PH. Tissue stores of oxalate are mobilized with return of kidney function, thereby exposing the new kidney to the damaging effects of hyperoxaluria (12–13). Thus, kidney graft survival has historically been poor with three year graft survival of 23% and 17% in LRD and DD recipients, respectively, as noted in the 1990 report of the European Dialysis and Transplant Registry (14). Although liver transplantation corrects the metabolic defect of PH1 (15), it requires removal of the entire native liver (16), and introduces substantial risks itself. Furthermore, if the patient had renal failure before the procedure there can still be a prolonged period of severe hyperoxaluria due to mobilization of pre-existing tissue oxalate stores following K+L transplantation.

Strategies to achieve optimal outcomes for patients with this rare metabolic disease have been problematic (17–21). We queried the International Primary Hyperoxaluria Registry (IHPR) to help understand modern management and to identify factors that provide best transplant outcomes for patients with primary hyperoxaluria.

Methods

Patients (registry & f/u)

The data for our study are derived from 203 PH patients entered in the IPHR. Due to the rarity of PH, the voluntary IPHR registry was established in 2004 to facilitate a more complete characterization of outcomes for PH patients (7). The registry provides observational data only. Patients are characterized as fully as possible at time of PH diagnosis (demographics, symptoms, stone history, urine and plasma oxalate levels, renal function, treatments and genotyping). Information from annual follow-up visits is recorded and includes updates on renal function, stone events, urine and blood chemistry, and PH treatments, as well as vital status. Details such as dialysis regimens and immune suppression management are not captured by the registry. End stage kidney disease (ESKD) was defined as return to maintenance dialysis or renal transplantation. Renal graft loss was defined as the need for resumption of dialysis or retransplantation. Hepatic graft loss was defined as the need for retransplantation or death due to hepatic failure.

Laboratory Methods

The diagnosis of PH was confirmed by [1] hepatic enzyme analysis documenting deficiency of AGT or GRHPR, [2] molecular genetic testing showing mutations in AGXT or GRHPR, or [3] marked hyperoxaluria in an appropriate clinical setting and in the absence of a secondary cause (22–24). In the IPHR the earliest transplants were performed before the availability of either hepatic enzyme analysis or molecular genetic testing for PH. Where diagnosis was by clinical criteria, PH type was established by elevations of glycolate (PH1) or glycerate (PH2) in urine or blood (22). Urine and plasma oxalate and serum creatinine levels were reported by the treating physician and in this study converted to common units.

Statistical Analysis

The primary analysis was based on first kidney (K) transplant outcomes. Cumulative event-free rates following first transplant were estimated using Kaplan-Meier curves. The logrank test and the Cox proportional hazards model were used to evaluate the association of potential risk factors with outcomes. When all K transplants per patient were included, the sandwich variance estimator (aggregated over patients) (25) was used to account for potential dependencies. Overall survival, graft survival (death counted as an event) and censored graft survival (death with a functioning allograft is not an event) outcomes were considered. Results for graft survival and censored graft survival are very similar as only 3 patients died with a functioning first kidney graft. Urine and plasma oxalate levels pre and post transplant were compared using the signed rank test. Trends in urine oxalate excretion following transplant were estimated using slopes derived from within patient linear regression. For clarity of presentation, quantitative factors (e.g. year of transplant) were dichotomized at the median. The signed rank test was applied to the slopes to test for trend. All tests were two-sided with an alpha level of 0.05.

Results

Patient cohort

Sixty-one of 203 (30%) patients in the IPHR were identified with a documented kidney (K) or liver (L) transplant. One patient with a liver-only transplant and 2 with liver transplants 3 and 5 years prior to their first kidney transplant were excluded from further analysis herein, leaving 58 patients with a kidney transplant, among whom 26 received a liver (L) transplant concomitant with their first kidney transplant (K+L, Table 1). Overall, the 58 patients have received 84 kidney transplants (44 K-only, 40 K+L)). Among the 32 patients with an initial K-only transplant, 22 received second kidney transplants (10 K, 12 K+L). Among the 26 patients with an initial K+L transplant, 1 received a second kidney transplant (K only). Outcomes of the first kidney transplant are the primary focus of this analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of first renal allografts in 58 PH patients

| Sex | |

| Female | 32 (55%) |

| Male | 26 (45%) |

| Age at PH Diagnosis, yrs | |

| Mean (SD) | 21.9 (18.92) |

| Median (25th, 75th) | 18 (7, 34.0) |

| Range | (0.0–74.0) |

| PH type | |

| PH Type 1 | 56 (96.6%) |

| PH Type 2 | 1 (1.7%) |

| Unknown | 1 (1.7%) |

| Age at first Kidney Transplant, yrs | |

| Mean (SD) | 28.2 (17.47) |

| Median (25th, 75th) | 25 (16.0, 39.0) |

| Range | 1.0–74.0 |

| Days on dialysis prior to first Transplant (n=43) | |

| Mean (SD) | 396.2 (451.11) |

| Median (25th, 75th) | 225.0 (125, 426) |

| Type of first Transplant | |

| Kidney only | 32 (55.2%) |

| Kidney + Liver | 26 (44.8%) |

| First Transplant Result | |

| Still functioning | 32 (56.1%) |

| Lost | 26 (43.9%) |

| Rejection | 5 |

| Early non-function | 3 |

| Oxalosis | 10 |

| Chronic allograft nephropathy | 6 |

| Other | 2 |

| Current Renal Status | |

| Functioning graft | 43 (74.1%) |

| Dialysis | 3 (5.2%) |

| Deceased | 12 (20.7%) |

First kidney transplant outcome

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for the kidney transplant cohort. Diagnosis of PH was confirmed by hepatic enzyme analysis (n= 40), molecular genetic testing (n=4), or clinical criteria (n=14). Fifty-six patients had PH1; one had PH2, and PH type was unknown in one who underwent transplantation and was lost to follow-up before PH type was established. Median age at PH diagnosis was 18 years, while median age at ESKD was 24, and at first kidney transplant 25 years. Among 47 patients with a known diagnosis of PH prior to transplantation, median time from diagnosis of PH to subsequent transplantation was 38 months (range 0.1 to 455 months). In 11 patients, PH diagnosis was established only after renal transplantation (median 9.1 months, range 1 to 200 months following transplantation). The diagnosis of PH was suggested by oxalate deposits in allograft tissue obtained by biopsy or allograft nephrectomy for impaired kidney graft function in 5 of these patients, 2 of whom also had stone formation in the allograft. One patient was investigated for overall decline in health following allograft failure. Following first transplant, 26 patients experienced kidney graft loss, with 10 due to oxalosis, 5 due to acute or chronic rejection (2 of which also appeared to have oxalate deposition as a contributing factor), 6 from chronic allograft nephropathy (2 of which also had oxalosis noted), 3 due early nonfunction and 2 due to other or unknown causes (Table 1).

At last follow-up (May 2009), 46 of 58 patients are living (43 with a functioning kidney allograft, 3 on dialysis) at a mean of 6.8 yrs after kidney transplantation. Among those with functioning grafts, median serum creatinine was 1.4 mg/dl and was not different between K and K+L. Twelve patients were deceased, including 9 with prior graft loss and 3 who died with a functioning first kidney allograft. Causes of death were oxalosis and complications of renal failure (n=4), sepsis and multiorgan failure (n=2), hepatic failure following liver transplant (n=1), GI bleed (n=1), post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) (n=1), auto accident (n=1), and unknown (n=2). Overall death censored graft survival, renal graft survival, and patient survival (SE) at 5 years following transplantation were 55(8)%, 49(8)%, and 92(4)%, respectively.

We determined associations of factors with graft loss and death censored graft loss as shown in Table 2. Results for graft survival and censored graft survival are similar as only 3 patients died with a functioning first kidney graft. Kidney allograft outcomes appear better with K+L than with K transplant alone (death censored graft survival, p=.011; graft survival, p=.14; logrank test; Figures 1a and 1b), as well as with recent (2000–2009) transplants (death censored graft survival: p=.01; graft survival: p=.05; Figure 2). Compared to USRDS data, overall two year first kidney allograft outcome in PH patients in our cohort lagged behind that of kidney transplantation for ESKD of all causes prior to 2000, but now compares favorably with both living donor and deceased donor transplantation (Figure 3). The same trend is evident among our PH K only transplant recipients (2 year allograft survival before 2000 of 55.6 + 9.6 %, mean + SE, compared with 80.0 +17.9 % after that time) though small numbers of kidney alone transplants in recent years limit conclusions. Among more recent (since 2000) transplants, 84% were functioning at 3 years compared to only 55% of those that were performed before 2000. Though not statistically significant, those with kidney transplant before the diagnosis of PH was known did somewhat worse (p. 0.07, Figure 4). Since all were K alone, the delay in diagnosis until after transplant could confound graft outcome analysis of this group. Characteristics of transplant type (K vs. K+L) are compared in Table 3. Types of transplant and time period were highly confounded. Among recent first transplants, 24/29 (83%) were K+L compared with 2/29 (7%) before 2000. In an attempt to separate the effects of time and transplant type, we included both in a multivariate Cox regression model. While the overall model was significant, both individual effects (year and transplant type) were not, suggesting a shared effect due to their high correlation. Three K+L patients died with functioning allografts, resulting in lower patient survival at 5 years (67%) as compared to K (100%, p=.035).

Table 2.

Risk factors for first renal allograft survival in 58 PH patients

| Censored Graft Loss (n=26 events) | Graft Loss (n=29 events) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 5yr event rate,% (SE) | P-value* | 5yr event rate,% (SE) | P-value* | |

| All | 58 | 45 (8) | n/a | 51 (8) | n/a |

| Sex | 0.15 | 0.17 | |||

| Female | 32 | 36 (10) | 43 (10) | ||

| Male | 26 | 61 (15) | 64 (14) | ||

| Year of transplant | 0.012 | 0.051 | |||

| Before 2000 | 29 | 56 (9) | 59 (9) | ||

| 2000–07 | 29 | 33 (20) | 48 (19) | ||

| Age at transplant | 0.53 | 0.25 | |||

| <25 years | 28 | 42 (13) | 42 (13) | ||

| >=25 years | 30 | 46 (11) | 57 (11) | ||

| Dialysis prior to transplant | 0.47 | 0.17 | |||

| <= 243 days | 22 | 43 (14) | 43 (14) | ||

| >243 days | 21 | 58 (14) | 72 (12) | ||

| Unknown | 15 | n/a | n/a | ||

| Transplant prior to Diagnosis | 0.07 | 0.17 | |||

| Transplant Before | 11 | 59 (16) | 59 (16) | ||

| Transplant After | 47 | 41 (10) | 49(9) | ||

| Concurrent liver transplant | 0.011 | 0.14 | |||

| No | 32 | 55 (9) | 55 (9) | ||

| Yes | 26 | 29 (21) | 52 (18) | ||

Logrank test.

Figure 1.

Among PH patients, death censored first kidney allograft survival was better in those who received K+L transplants than K transplantation alone (A). Overall graft survival (B), however, did not differ significantly in K+L compared with K, due to deaths with functioning kidney allografts among the K+L recipients.

Figure 2.

First kidney allograft survival is improved after 2000 compared to earlier time for PH patients.

Figure 3.

Two year survival rates + SE of first kidney allografts of IPHR patients (PH) whose transplants were performed before year 2000 were 59 + 8.7 mean + SE % (95% CI 42–76%, median transplant year 1994, n = 29) compared to 84 + 9.1 % (95% CI 66–100%, median year 2005, n = 29) in 2000 or later. Shown for comparison are USRDS 2 year first kidney graft survival rates for deceased donor (DD) and living donor (LD) kidneys (42).

Figure 4.

Delay in the diagnosis of PH until after transplantation, which occurred in 19% of patients (dotted line labeled “Transplant (Tp) before Diagnosis (Dx)”), showed a trend toward earlier kidney allograft loss when compared with those in whom the PH diagnosis was made before transplant (solid line labeled “Tp after Dx”).

Table 3.

First Transplant Characteristics and Outcomes by Type of Transplant

| Kidney Alone (K), n=32 | Kidney and Liver (K + L), n=26 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transplant prior to year 2000, no. (%) | 27 (84.4%) | 2 (7.7%) | <0.001 |

| Age at PH diagnosis, yrs:mean (SD) | 25.4 (19.8) | 17.6 (17.2) | 0.08 |

| Age at ESRD, yrs: mean (SD) | 29.2 (17) | 24.1 (17) | 0.21 |

| Age at first transplant,yrs: mean (SD) | 30.5 (17.4) | 25.3 (17.4) | 0.28 |

| Transplant to last follow-up, yrs:Median (25th, 75th) | 9.7 (6.3, 14) | 1.3 (0.3, 3.2) | <0.001 |

| Patient survival (SE) at:** | 0.035 | ||

| 3yr | 100% (0) | 92% (7) | |

| 5yr | 100% (0) | 67% (16) | |

| 7yr | 88% (7) | 67% (16) | |

| 10 yr | 75% (9) | na |

Second transplant outcome

Among the 23 second kidney transplants (11 K, 12 K+L), 8 experienced kidney allograft loss (5 K, 3 K+L; 3 due to oxalosis, 2 to chronic allograft nephropathy, 1 due to rejection, 1 to primary non-function, and 1 unknown) and an additional 2 patients died 8.9 and 14.4 years following their second transplant with functioning kidney and liver allografts. Causes of death of the two who died with functioning allografts were post transplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD) and trauma from an automobile accident.

All transplant outcomes

Pooling data from all 84 transplants, there are a total of 44 K and 40 K+L (Table 1). Comparing K to K+L, 5-year kidney graft survival was 45% vs 64% (p=0.10), respectively, but death censored graft survival was 45% vs 78% (p=0.003).

Oxalate levels after transplantation

Plasma oxalate values pre and post transplant were available for 11 K+L patients, 6 first time K recipients, and 2 repeat K-alone transplants (Figure 5a and 5b). Plasma oxalate levels dropped rapidly between the last pre-transplant value to first post-transplant value for both K+L (median 67.1 to 10.4, p=<0.001) and K recipients (median 48.3 to 8.5, p=0.01). There was no significant difference in average plasma oxalate levels in the first 12 months post transplantation between K and K+L (median 6.6 and 7.3, respectively, p=0.27 rank sum test), nor was there a difference in post transplant plasma oxalate trends (p=0.26). Urine oxalate levels following transplant were available for 16 K+L patients (Figure 6). Urine oxalate levels dropped progressively but relatively slowly after transplant with a median slope of −0.35 mmol/24hrs/ yr (p<0.001). During the third year after K+L transplant 4/11 (36%) still had hyperoxaluria. By contrast, in patients with K alone, in whom the metabolic defect has not been corrected, marked hyperoxaluria persists indefinitely (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Plasma oxalate concentration declined rapidly following successful K+L (A) and K alone (B) transplantation, but remained above normal in most patients during the first year after transplant. The normal range for plasma oxalate levels (< 1.8 μmol/L) is shown in the area shaded gray.

Figure 6.

Urinary oxalate readings (and running average, solid line) from 16 PH recipients of K+L transplants. Normal urine oxalate (<0.46 mmol/1.73m2/24 hrs) is shown by the area shaded gray. Hyperoxaluria persisted in most patients for up to 3 years following transplantation. During the first year, marked hyperoxaluria was characteristic due to mobilization of pre-existing tissue stores of calcium oxalate deposited during renal failure.

Discussion

Prior to 1990 outcomes of transplantation in primary hyperoxaluria were poor, to the extent that the appropriateness of transplantation for patients with PH was questioned (14,26). Loss of function due to oxalate deposition in the transplanted kidney and death related to systemic oxalosis were particular problems. However, there has been substantial improvement in transplantation outcome among PH patients over the past several decades (27–29). For the cohort of patients in our study of the IPHR who received their first kidney transplant in the year 2000 or later, graft outcome now compares favorably with_kidney allograft survival rates for all U.S. recipients of kidney transplants for kidney failure of any cause (Figure 3) Greater use over time of combined liver and kidney transplantation as well as management strategies specific to primary hyperoxaluria appear important in the progress reflected in our experience and that of others (9,29). Wider availability of definitive diagnostic testing for PH (23), the intensive dialysis needs of PH patients (13,17,27,36,37) and the critical need to minimize the time between ESKD and transplantation have been increasingly appreciated (6,27,29). However, there is as yet no standard approach to transplantation of patients with PH.

The AGT enzyme defect that is the cause of PH type I is specific to hepatocytes. Complete removal of the native liver and orthotopic transplantation is required to correct the metabolic defect (16), since any remaining native liver cells with reduced or absent AGT enzyme activity would produce large amounts of oxalate. Thus, the benefits of correcting the metabolic defect must be weighed against the added morbidity and mortality associated with hepatectomy and orthotopic liver transplantation. Early reports from Europe suggested better outcomes with combined K + L transplantation (15,30) while those from the U.S. suggested equally good or better outcomes with K alone transplantation (18,31). Interestingly, our data, while showing better death censored kidney allograft outcomes in K+L transplantation (p=0 .011), did not show a difference in uncensored kidney allograft survival (p=0.14), where death is considered a graft loss. The difference is accounted for by 3 deaths in patients with functioning kidney grafts among the K+L recipients. Two of the deaths were related to post transplant immune suppression (one due to PTLD and one to Nocardia sepsis). The remaining death was due to trauma resulting from an automobile accident. Overall patient survival at 5 years was 100% in K (n=32) vs 67% in K + L (n=26, p = 0.035), though has improved in more recent K + L transplants.

Oxalosis of the transplanted kidney represents an important challenge to long-term allograft survival in patients with PH (9,13,27). In the IPHR, 38% of first kidney allograft failures were caused by recurrent oxalosis. Though liver transplantation can provide correction of the metabolic deficiency that is the cause of PH type I, it appears no more effective than kidney transplantation alone in reduction of plasma oxalate during the first year after transplantation. There is a prompt fall in plasma oxalate concentrations following either K or K+L transplantation (Fig 5 a, b). Nonetheless, urine oxalate remains markedly elevated for many months or even years after successful liver transplantation (Figure 6). This is due to tissue stores of calcium oxalate that are only slowly mobilized with subsequent kidney excretion (13,27). Thus the kidney allograft remains at risk for oxalosis long after correction of the underlying PHI metabolic defect (13,27). The kidney allograft is especially vulnerable to the injurious effects of high urine oxalate and deposition of calcium oxalate crystals in the renal parenchyma (32,33).

The time required for resolution of hyperoxaluria following liver transplantation varies widely, occurring most rapidly in those who undergo transplantation within 6 months after reaching ESKD and who have undergone intensive (daily) dialysis (29). Time on dialysis did not correlate with transplant outcome in our series, unlike that of Jamieson (29). This is perhaps related to the intensive dialysis that a number of them received before transplantation or alternatively to the relatively small number of patients dialyzed in our study who were on dialysis for a year or more (Table 2). Nevertheless, in our cohort 36% still had hyperoxaluria during the third year following transplantation.

What can be done to further improve outcomes of transplantation in PH? The large proportion (19%) of patients in whom the diagnosis of PH was not recognized until there was compromise or failure of a first kidney allograft is particularly alarming. Among such patients early graft loss predominated, with renal graft survival of only 62% at 1 year following transplantation, compared with 86% in those whose PH diagnosis was known prior to transplant. With availability of current diagnostic capabilities (22,23,34), most delays in diagnosis are now related to lack of familiarity with the disease. Recognition of PH before transplantation is important in identifying those patients at the outset who will have improved outcomes with K + L transplantation. In addition, it affords the opportunity to better preserve native renal function (5,35), minimize systemic oxalosis with intensive dialysis after renal failure ensues (36), and better protect the kidney allograft from oxalate injury by maintaining a high volume diuresis and inhibition of calcium oxalate crystallization with phosphate or citrate medication (17,27,37). PH should be considered as a potential cause of renal failure in all transplant candidates with a history of recurrent calcium oxalate kidney stones, nephrocalcinosis, or interstitial renal disease of undetermined etiology. With this approach, harmful delays in diagnosis that continue to be reported both in the U.S. and Europe (9,38) can be avoided.

Strategies for individual patients with type I PH based on molecular genotyping may be important in achieving the best outcome (9,19). Patients who are fully responsive to pharmacologic doses of pyridoxine, usually those homozygous for the G170R mutation of AGXT, can maintain normal or near normal urine oxalate excretion rates for many years while on pyridoxine treatment (39). Though beyond the scope of the present report, whether native hepatectomy and liver transplantation is indicated in such patients will benefit from further study.

For patients with type II disease, which account for approximately 10% of PH patients, kidney alone transplantation has been the recommended approach (6,27). Unlike AGT which resides almost entirely within hepatocytes, the GRHPR enzyme deficient in PH type II is found in multiple body tissues (40). There has been no evidence to date to_confirm that liver transplantation corrects this metabolic defect. Our single patient who required transplantation for PH type II maintained good allograft function and was free of stone disease and nephrocalcinosis for 31 years following kidney alone transplantation despite ongoing hyperoxaluria. This is in keeping with the natural history of PH II in which many patients maintain native kidney function into their 5th to 6th decade (6,41).

Limitations of our study include the voluntary nature of the registry, and therefore a potentially biased sampling of patients, and lack of randomization in comparing K versus K+L. Though adjusted for in the analysis, the much longer follow-up in patients with K only versus K+L transplantation must also be considered in interpretation of the results. Relatively small sample size and small numbers of events, due to the rarity of primary hyperoxaluria, limits the ability to perform multivariate analyses adjusting for multiple confounders.

Conclusions

Outcome of transplantation in patients with primary hyperoxaluria has improved substantially over the past decade, now comparing favorably with the outcomes of kidney_transplantation for other causes. Significant challenges remain, including the timely diagnosis of primary hyperoxaluria and in prevention of oxalate injury to kidney allografts as a_result of the marked hyperoxaluria that often persists for years following correction of the metabolic defect. Recognition of PH prior to transplantation requires a high index of suspicion with appropriate diagnostic testing of a patient of any age with ESKD who has nephrocalcinosis and/or a history of calcium stone disease. The PH type, and the genotype in PH I, are important considerations in decisions regarding kidney alone versus combined liver and kidney transplantation. Protection of the kidney allograft from oxalate injury requires particular management strategies.

Though the improvement in outcomes over time is encouraging, liver transplantation is at best a crude form of AGT enzyme replacement. Alternatives such as hepatocellular transplantation should continue to be actively explored. New approaches to reduce oxalate induced renal injury, and thus to eliminate the development of renal failure in this population, are needed.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and families who participated. We also greatly thank the IPHR Investigators who so generously provided clinical data: D Adey (San Francisco, California, USA), S Ahmed, M Aigbe (Las Vegas, Nevada, USA), S Alexander, M Anders (Buenos Aires, Argentina), N Amin (Los Angeles, California, USA), Dr. Ashette (New York, NY, USA), JR Asplin (Chicago, Illinois, USA), N Azam (Houston, Texas, USA), N Balakrishnan (Coimbatore Tamilivadu, India), S Bhandare, M Baum (Boston, Massachusetts, USA), B Becker (Wisconsin, USA), David Beckman (Faribault, Minnesota, USA), Dr. Beiken (New York, NY, USA), S Belani (Petaluma, California, USA), A Bellucci (Lake Success, New York, USA), R Berkseth (Minneapolis, MN, USA), P Berry (Austin, Texas, USA), N Bhakta (Los Angeles, California, USA), A Bhat (Roseville, California, USA), S Bhupalam (East Lansing, Michigan, USA), M Bia (New Haven, Connecticut, USA), T Blydt-Hansen (Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada), R Bousquet (Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada), M Braun (Houston, Texas, USA), E Brewer (Houston, Texas, USA), C Brueggmeyer (Jacksonville, Florida, USA), T Bunchman (Grand Rapids, Michigan, USA), L Butani (Sacramento, California, USA), M Cadnapaphornchai (Aurora, Colorado, USA), E Castillo-Velarde Lima, Peru), MJ Choi (Baltimore, Maryland, USA), F Chybowski (Appleton, Wisconsin, USA), F Ciuitarese (Carneigie, Pennsylvania, USA), L Copelovitch (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA), F Corbin (Quebec, Canada), H Corey (Morristown, New Jersey, USA), D Creemers (Netherlands), R Cunningham (Cleveland, Ohio, USA), K Dalinghaus (Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada), I Davis (Cleveland, Ohio, USA), C de Souza (Uruguay), M DeBeukelaer (Toledo, Ohio, USA), V Delaney (Hawthorne, New York, USA), P Devarajan (Cincinnatti, Ohio, USA), Z Dolezel (Czech Republic), HA Doll (Tallahasse, Florida, USA), P Douville (Quebec, Canada), S Ecklund (Sioux Falls, South Dakota, USA), K Eidman (Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA), M Emmett (Alvardo, Texas, USA), D Ford (Aurora, Colorado, USA), J Foreman (Durham, North Carolina, USA), C Fritsche (Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA), S Garcia (Barcelona, Spain), D Geary (Toronto, Ontario, Canada), D Gipson (Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA), D Goldfarb (Cleveland, Ohio, USA), B Greco (Springfield, Massachusetts, USA), L Greenbaum (Atlanta, Georgia, USA), W Haley (Jacksonville, Florida, USA), P Hall (Cleveland, Ohio, USA), M Hames (Greenville, North Carolina, USA), CD Hanevold (Seattle, Washington, USA), F Harris (Metairle, Louisiana, USA), G Hart (Charlotte, North Carolina, USA), E Harvey (Toronto, Ontario, Canada), RL Heilman (Scottsdale, Arizona, USA), R Helman (Duluth, Minnesota, USA), A Herndon (Birmingham, Alabama, USA), J Herrin (Boston, Massachusetts, USA), M Hertl (Boston, Massachusetts, USA), G Hidalgo (Chicago, Illinois, USA), S Hmiel (St. Louis, Missouri, USA), B Hoppe (Cologne, Germany), H Hotchkiss (New Brunswick, NJ, USA), T Hunley (Nashville, Tennessee, USA), Dr. Husmann (Tennessee, USA), J Johnston (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA), B Kaiser, U Kannapadi (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA), C Kashani (Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA), F Kaskel (Bronx, New York, USA), E Kendrick (Seattle, Washington, USA), O Khan (Chicago, Illinois, USA), S Knohl (Syracuse, New York, USA), R Kossman (Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA), A Krambeck (Indianapolis, IN, USA), C Langman (Chicago, Illinois, USA), L Larch (Clarksville, IN, USA), J Leiser (Indianapolis, IN, USA), S Lerman (Los Angeles, California, USA), DL Levy (Bangor, Maine, USA), J Lingeman (Indianapolis, IN, USA), DS Lirenman (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada), N Maalouf (Chattanooga, Tennessee, USA), M Maddy (Duluth, Minnesota, USA), MA Mansell (London, United Kingdom), M Martin (Worcester, Massachusetts, USA), R Mathias (San Francisco, California, USA), M Mauer (Minneapolis, MN, USA), M May (Jacksonville, Florida, USA), M McHugh (Columbus, OH, USA), P Metcalfe (Edmonton, Alberta, Canada), B Morgenstern (Phoenix, Arizona, USA), G Murphy (Greenville, North Carolina, USA), M Narkewicz (Denver, Colorado, USA), M Navarro (Madrid, Spain), HG Pohl (Washington, DC, USA), H Powell (Parkville, Victoria, Australia), I Randeree (Umhlanga Rocks, South Africa), V Rao (Omaha, Nebraska, USA), D Raskin (Phoenix, Arizona, USA), Dr. Ravichandran (India), L Restall (Dallas, Texas, USA), C Richardson (Tacoma, Washington, USA), M Rocklin (Denver, Colorado, USA), P Sacks (Phoenix, Arizona, USA), M Sanderson (Saint Paul, Minnesota, USA), JD Scandling (Palo Alto, California, USA), J Sharma (Bangalore, India), M Sheehan (Denver, Colorado, USA), K Sievers (Rolla, Missouri, USA), E Simon (Boston, Massachusetts, USA), R Sirota (Willow Grove, Pennsylvania, USA), C Smith (Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA), M Sobel (Westerville, OH, USA), Dr. Somasundaram (Indianapolis, IN, USA), T Starzl (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA), J Steinke (Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA), D Steward, M Suarez (Houston, Texas, USA), JM Symons (Seattle, Washington, USA), IYS Tang (Chicago, Illinois, USA), J Tariq (Pakistan), M Teruel (Fort Collins, Colorado, USA), A Tolaymat (Jacksonville, Florida, USA), MM Tomsho (Summersville, West Virginia, USA), A Torres (La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain), S Tuchman (Washington, DC, USA), MA Turman (Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, USA), R Unwin (London, United Kingdom), R Venick (Los Angeles, California, USA), S Venkatesh (Nashville, Tennessee, USA), A Vera (Bogota, Columbia), H Viko (Oslo, Norway), R Villa (Lubbock, Texas, USA), J Wang (Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA), B Warady (Kansas City, Kansas, USA), B Warshaw (Atlanta, Georgia, USA), C Weimer (Thibodaux, Louisiana, USA), J Weinstein (Dallas, Texas, USA), RA Weiss (Valhalla, New York, USA), P Wertsch (Madison, Wisconsin, USA), J Wesson (Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA), C Wong (Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA), W Wong (Boston, Massachusetts, USA), E Worcester (Chicago, Illinois, USA), O Yadin (Los Angeles, California, USA), V Yiu (Edmonton, Alberta, Canada).

Our appreciation goes to Julie B. Olson, R.N., Barb Seide, Chuck Madsen, Mark Manneman, and Susan Rogers, coordinators of the Mayo Clinic Hyperoxaluria Center and the Rare Kidney Stone Consortium for their tireless efforts.

This work would not have been possible without funding from the Oxalosis and Hyperoxaluria Foundation and the NIDDK (DK73354 and U54KD083908).

Footnotes

This material was presented, in part, at the American Society of Nephrology in 2008. J Am Soc Nephrol 19:101A, 2008.

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

References

- 1.Danpure CJ, Jennings PR. Peroxisomal alanine:glyoxylate aminotransferase deficiency in primary hyperoxaluria type 1. FEBS letter. 1986;201:20–24. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)80563-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mistry J, Danpure CJ, Chalmers RA. Hepatic D-glycerate dehydrogenase and glyoxylate reductase deficiency in primary hyperoxaluria type 2. Biochem Soc Trans. 1988;16:626–627. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vervaet BA, Verhulst A, D'Haese PC, De Broe ME. Nephrocalcinosis: new insights into mechanisms and consequences. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:2030–2035. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leumann E, Hoppe B. The primary hyperoxalurias. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:1986–1993. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1291986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milliner DS, Eickholt JT, Bergstralh E, Wilson DM, Smith LH. Primary hyperoxaluria: Results of long-term treatment with orthophosphate and pyridoxine. New Engl J Med. 1994;331:1553–1558. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412083312304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoppe B, Beck BB, Milliner DS. The primary hyperoxalurias. Kidney Int. 2009;75:1264–1271. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lieske JC, Monico CG, Holmes WS, Bergstralh EJ, Slezak JS, Rohlinger AL, et al. International Registry for Primary Hyperoxaluria. Am J Nephrol. 2005;25:290–296. doi: 10.1159/000086360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Woerden CS, Groothoff JW, Wanders RJ, Davin J, Wijburg FA. Primary hyperoxaluria type 1 in the Netherlands: prevalence and outcome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:273–279. doi: 10.1093/ndt/18.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harambat J, Fargue S, Acquaviva C, Gagnadoux MF, Janssen F, Liutkus A, et al. Genotypephenotype correlation in primary hyperoxaluria type 1: the p.Gly170Arg AGXT mutation is associated with a better outcome. Kidney Int. 2010;77:443–449. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leuman EP, Niederwieser A, Fanconi A. New aspects of infantile oxalosis. Ped Nephrol. 1987;1(3):531–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00849265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barratt TM, van't Hoff WG. Are there guidelines for a strategy according to GFR, plasma oxalate determination and the risk of oxalate accumulation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1995;10:22–23. doi: 10.1093/ndt/10.supp8.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katz A, Kim Y, Scheinman J, Najarian JS, Mauer SM. Long-term outcome of kidney transplantation in children with oxalosis. Transplant Proc. 1989;21:2033–2035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruder H, Otto G, Schutgens RBH, Querfeld U, Wanders RJA, Herzog KH, et al. Excessive urinary oxalate excretion after combined renal and hepatic transplantation for correction of hyperoxaluria type 1. Eur J Pediatr. 1990;150:56–58. doi: 10.1007/BF01959482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broyer M, Brunner FP, Brynger H, Dykes SR, Ehrich JHH, Fassbinder W, et al. Kidney transplantation in primary oxalosis: data from the EDTA registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1990;5:332–336. doi: 10.1093/ndt/5.5.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watts RWE, Morgan SH, Danpure CJ, Purkiss P, Calne Y, Rolles R, et al. Combined hepatic and renal transplantation in primary hyperoxaluria type 1: clinical report of 9 cases. Am J Med. 1990;90:179–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Danpure CJ. Primary hyperoxaluria. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. The metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease. ed 8 McGraw-Hill; New York: 2001. pp. 3323–3367. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Latta K, Jamieson NV, Scheinman JI, Scharer K, Bensman A, Cochat P, et al. Selection of transplantation procedures and perioperative management in primary hyperoxaluria type 1. Nephrol Dial Trans. 1995;8:53–57. doi: 10.1093/ndt/10.supp8.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarborio P, Scheinman JL. Transplantation for primary hyperoxaluria in the United States. Kidney Int. 1999;56:1094–1100. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marangella M. Transplantation strategies in type 1 primary hyperoxaluria: the issue of pyridoxine responsiveness. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:301–303. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cochat P, Scharer K. Should liver transplantation be performed before advanced renal insufficiency in primary hyperoxaluria type 1? Pediatr Nephrol. 1993;7:212–218. doi: 10.1007/BF00864408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eytan Mor MD, Weismann I. Current Treatment for primary hyperoxaluria type 1: When should liver/kidney transplantation be considered? Pediatr Transplant. 2009;13:805–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2009.01230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milliner DS. The primary hyperoxalurias: An algorithm for diagnosis. Am J Nephrol. 2005;25:154–160. doi: 10.1159/000085407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monico CG, Rossetti S, Schwanz H, Olson J, Lundquist P, Dawson D, et al. Comprehensive mutation screening in 55 probands with type 1 primary hyperoxaluria shows feasibility of a gene-based diagnosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1905–1914. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006111230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams E, Rumsby G. Selected exonic sequencing of the AGXT gene provides a genetic diagnosis in 50% of patients with primary hyperoxaluria type 1. Clin Chem. 2007;53:1216–1221. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.084434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin DY, Wei LJ. The robust inference for the Cox proportional hazards model. J Am Stat Assoc. 1989;84:1074–79. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson RE. A report from the ACS/NIH renal transplant registry. Renal transplantation in congenital and metabolic disease. JAMA. 1975;232:148–153. doi: 10.1001/jama.1975.03250020022018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monico CG, Milliner D. Combined liver-kidney transplantation and kidney-alone transplantation in primary hyperoxaluria. Liver Transplant. 2001;7:954–963. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.28741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cibrik DM, Kaplan B, Arndorfer JA, Meier-Kriesche HU. Renal allograft survival in patients with oxalosis. Transplantation. 2002;74:707–710. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200209150-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jamieson NV. A 20-year experience of combined liver/kidney transplantation for primary hyperoxaluria (PH1): The European PH1 transplant registry experience 1984–2004. Am J Nephrol. 2005;25:282–289. doi: 10.1159/000086359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jamieson NV. The European Primary Hyperoxaluria Type 1 Transplant Registry report on the results of combined liver/kidney transplantation for primary hyperoxaluria 1984–1994. European PH1 Transplantation Study Group. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1995;10:33–37. doi: 10.1093/ndt/10.supp8.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scheinman JI, Alexander M, Campbell ED, Chan JC, Latta K, Cochat P. Transplantation for primary hyperoxaluria in the USA. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1995;10(8):42–46. doi: 10.1093/ndt/10.supp8.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verkoelen CF, Verhulst A. Proposed mechanisms in renal tubular crystal retention. Kidney Int. 2007;72:13–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pinheiro HS, Camara NO, Osaki KS, De Moura LA, Pacheco-Silva A. Early presence of calcium oxalate deposition in kidney graft biopsies is associated with poor long-term graft survival. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:323–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams E, Rumsby G. Selected exonic sequencing of the AGXT gene provides a genetic diagnosis in 50% of patients with primary hyperoxaluria type 1. Clin Chem. 2007;53:1216–1221. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.084434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fargue S, Harambat J, Gagnadoux MF, Tsimaratos M, Janssen F, Llanas B, et al. Effect of conservative treatment of the renal outcome of children with primary hyperoxaluria type 1. Kidney Int. 2009;76:767–773. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Illies F, Bonzel KE, Wingen AM, Latta K, Hoyer PF. Clearance and removal of oxalate in children on intensified dialysis for primary hyperoxaluria type 1. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1642–1648. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scheinman JI, Najarian JS, Mauer SM. Successful strategies for renal transplantation in primary oxalosis. Kidney Int. 1984;25:804–811. doi: 10.1038/ki.1984.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoppe B, Langman C. A United States survey on diagnosis, treatment and outcome of patients with primary hyperoxaluria. Pediatr Nephrol. 2003;18:986–991. doi: 10.1007/s00467-003-1234-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monico CG, Rossetti S, Olson JB, Milliner DS. Pyridoxine effect in type I primary hyperoxaluria is associated with the most common mutant allele. Kidney Int. 2005;67:1704–1709. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giafi CF, Rumsby G. Primary hyperoxaluria type 2: enzymology. J Nephrol. 1998;11:29–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Milliner DS, Wilson DM, Smith LH. Phenotypic expression of primary hyperoxaluria: comparative features of types I and II. Kidney Int. 2001;59:31–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. http://www.ustransplant.org/annual_reports/current/survival_rates.html.