Abstract

The heterotrimeric G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) represent the largest and most diverse family of cell surface receptors and proteins. GPCRs are widely distributed in the peripheral and central nervous systems and are one of the most important therapeutic targets in pain medicine. GPCRs are present on the plasma membrane of neurons and their terminals along the nociceptive pathways and are closely associated with the modulation of pain transmission. GPCRs that can produce analgesia upon activation include opioid, cannabinoid, α2-adrenergic, muscarinic acetylcholine, γ-aminobutyric acidB (GABAB), group II and III metabotropic glutamate, and somatostatin receptors. Recent studies have led to a better understanding of the role of these GPCRs in the regulation of pain transmission. Here, we review the current knowledge about the cellular and molecular mechanisms that underlie the analgesic actions of GPCR agonists, with a focus on their effects on ion channels expressed on nociceptive sensory neurons and on synaptic transmission at the spinal cord level.

Keywords: Analgesia, Dorsal root ganglion, G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K+ channels, Spinal cord, Synaptic transmission, Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels

1. Introduction

The heterotrimeric G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are one of the largest and most diverse protein families in the mammalian genome. Despite their molecular and functional diversity, all GPCRs share a similar structure, which consists of seven transmembrane domains linked by alternating intracellular and extracellular loops. Extracellular domains, which vary among the different classes of GPCRs, contribute to ligand recognition and binding, but coupling to G proteins is determined mainly by interactions with intracellular domains (Lu et al., 2002; Kroeze et al., 2003; Kristiansen, 2004). When a GPCR agonist binds to the extracellular domain, it induces a change in conformation of the receptor. This, in turn, leads to coupling to and activation of one or more G proteins inside the cell.

The G proteins consist of three subunits: α, β, and γ. Work to date has resulted in identification of 17 genes encoding the α subunit, 5 encoding the β subunit, and 12 encoding the γ subunit (Hur and Kim, 2002; Neves et al., 2002). Activation of G proteins by GPCRs results in dissociation of the Gα subunit from the Gβγ subunits. The Gβγ subunits function as a dimer and can activate a diverse array of effectors such as enzymes and ion channels (Neves et al., 2002; Sadja et al., 2003). On the other hand, the Gα subunits have a key role in determining the receptor coupling specificity and can influence the efficiency of ion channel modulation by Gβγ subunits (Jeong and Ikeda, 2000; Leaney et al., 2000; Ivanina et al., 2004; Amaya et al., 2006). On the basis of their G protein-coupling preference, GPCRs can be broadly classified into four major categories: Gαs-, Gαi/o-, Gαq/11-, and Gα12/13-coupled receptors (Hur and Kim, 2002; Neves et al., 2002). Almost all GPCR agonists that have an analgesic action are coupled to Gi/o proteins.

GPCRs regulate the function of ion channels, which play an essential role in the function of neurons by mediating electrical currents and regulation of selective ion concentrations across the cell membrane. GPCRs can affect ion channel function through two mechanisms: (1) indirect phosphorylation of ion channels through second messengers such as protein kinase C and certain tyrosine kinases, and (2) direct Gβγ binding to ion channels (Diverse-Pierluissi et al., 2000; Mark and Herlitze, 2000; Diverse-Pierluissi, 2005). In neurons, Ca2+ entry through Ca2+ channels is essential for synaptic transmission. Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) are fundamental components of the presynaptic release machinery through which neurotransmitter release can be modulated (Hille, 1994). There are five subtypes of VGCCs: the L-type (Cav1), N-type (Cav2.2), P/Q-type (Cav2.1), R-type (Cav2.3), and T-type (Cav3). The N-type and P/Q-type are the most important VGCCs for synaptic transmission. Indeed, the synaptic release of glutamate depends primarily on the activity of N-type and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels, which are heterogeneously distributed on glutamatergic afferent terminals (Luebke et al., 1993; Wheeler et al., 1996; Reid et al., 1997). The modulation of VGCCs by activation of GPCRs critically controls presynaptic Ca2+ entry and hence neurotransmitter release. Inhibition of VGCCs by GPCRs typically includes a rapid, membrane-delimited inhibition mediated by direct, voltage-dependent interactions between G protein βγ subunits and a slower, voltage-independent modulation involving soluble second messenger molecules. Blocking N-type VGCCs in the spinal cord effectively blocks nociceptive transmission and produces profound analgesia in animals and humans (Wang et al., 2000; Staats et al., 2004).

GPCRs also modulate the inwardly rectifying K+ channels (Kir), especially the Kir3 subfamily (Kir3.1-Kir3.4). Kir3 channels, also known as G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K+ (GIRK) channels, are important in maintaining the resting membrane potential duration and excitability. The GIRK channels are activated through direct binding of the Gβγ subunits to the channel after stimulation of GPCRs (Sadja et al., 2003). GPCR agonists likely inhibit pain transmission through a combination of inhibition of VGCCs to reduce excitatory neurotransmitter release from presynaptic terminals of nociceptive sensory neurons and direct hyperpolarization of second-order neurons via activation of GIRK channels (Kohno et al., 1999; Pan et al., 2002a; Marker et al., 2005).

In the following sections, we review the current knowledge about the cellular and molecular mechanisms that underlie the analgesic actions of several classes of GPCR agonists, including agonists of opioid, cannabinoid, α2-adrenergic, muscarinic acetylcholine, γ-aminobutyric acidB (GABAB), group II and III metabotropic glutamate, and somatostatin receptors. The major emphasis is on the effects of the GPCR agonists on nociceptive sensory neurons and synaptic transmission at the spinal cord level.

2. Opioid receptors

Four major opioid receptors have been cloned: μ-, δ-, κ-, and nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptors (opioid receptor-like 1 [ORL1]) (Evans et al., 1992; Chen et al., 1993; Fukuda et al., 1993; Nishi et al., 1993; Thompson et al., 1993; Mollereau et al., 1994). The μ-, δ-, and κ-opioid receptors are highly conserved in regions spanning the transmembrane domains and intracellular loops. The amino acid sequences of these three receptors are about 60% identical to each other. They are activated both by endogenously produced opioid peptides (i.e., endomorphin-1 and-2, enkephalins, and dynorphins) and by exogenously administered opioid receptor agonists, such as morphine. The human ORL1 has approximately 50% sequence homology to murine μ-, δ-, κ-opioid receptors (Mollereau et al., 1994).

2.1. Distribution of opioid receptors in pain pathways

In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry studies have shown that in the spinal dorsal horn, μ-, δ-, κ-, and ORL1-opioid receptor mRNA and proteins are expressed predominantly in the superficial laminae (laminae I and II), where nociceptive C- and Aδ-fibers of primary afferents principally terminate and where Met-enkephalin immunoreactive-fibers are distributed (Maekawa et al., 1994; Robertson et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2002; Pettersson et al., 2002). Also, dense expression of μ-, δ-, κ-, and ORL1-opioid receptor mRNA and proteins is present in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons (Dado et al., 1993; Maekawa et al., 1994; Wang and Wessendorf, 2001; Pettersson et al., 2002).

The expression level of μ-, δ-, and κ-opioid receptors is influenced by different pain conditions. For example, nerve injury reduces μ-opioid receptor expression in the spinal dorsal horn (Porreca et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 1998b), and the analgesic effect of μ-opioid agonists is reduced in chronic pain caused by nerve ligation injury (Arner and Meyerson, 1988; Kim and Chung, 1992; Porreca et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 1998b). In a rat model of diabetic neuropathy, functional μ-opioid receptors, but not the total number of opioid receptors, are attenuated in the spinal dorsal horn (Chen et al., 2002; Chen and Pan, 2003a). In contrast, κ-opioid receptor is upregulated in the DRG neurons of mice following nerve injury (Sung et al., 2000). Also, δ-opioid receptors seem to be located mostly in the cytoplasm (Zhang et al., 1998a), but chronic inflammatory pain can enhance the surface availability of δ-opioid receptors in rat DRG neurons (Morinville et al., 2004; Gendron et al., 2006). Chronic morphine treatment also enhances the surface expression of δ-opioid receptors and may potentiate the efficacy of the δ-opioid receptor agonists (Morinville et al., 2004; Gendron et al., 2006).

2.2. Antinociceptive effect of opioid receptor agonists

The μ opioid agonists, such as morphine and fentanyl, are still the gold standard for the treatment of moderate and severe pain. It is well known that systemic and intrathecal administration of μ-opioid agonists in animals and in humans produces powerful analgesia (Wigdor and Wilcox, 1987; Onofrio and Yaksh, 1990; Chen and Pan, 2006a). Analyses of opioid receptor knockout mice have clearly shown that the μ-opioid receptors play a central role in opioid-induced analgesia (Matthes et al., 1996; Simonin et al., 1998; Zhu et al., 1999). The μ-opioid receptors in the DRG and spinal cord are critically involved in pain transmission, as indicated by studies showing that intrathecal injection of μ-opioid receptor antagonists abolishes the inhibitory effect on dorsal horn neurons and the analgesic action produced by μ opioids administered systemically (Chen et al., 2005b; Chen and Pan, 2006a). Also, intrathecal administration of the δ-opioid receptor agonist [D-Pen2,D-Pen5]-enkephalin (DPDPE) produces a dose-dependent analgesia (Hammond et al., 1998).

Interestingly, depletion of TRPV1-expressing sensory neurons reduces presynaptic μ-opioid receptors but paradoxically potentiates the analgesic effect of μ-opioid agonists (Chen and Pan, 2006b). Furthermore, removal of TRPV1-expressing sensory neurons attenuates the development of opioid analgesic tolerance in rats (Chen et al., 2007b). These findings suggest that μ-opioid receptors are probably coupled to different signaling pathways and heterogeneously expressed in different phenotypes of DRG neurons (Wu et al., 2004). Opioid receptors can form heterodimers in neurons (Cheng et al., 1997; Jordan and Devi, 1999; George et al., 2000; Wessendorf and Dooyema, 2001), which may alter the agonist binding properties and functional effects (Jordan and Devi, 1999; Charles et al., 2003). For instance, while the heterodimer consisting of the κ- and δ-opioid receptors synergistically increases the binding of their selective agonists, coexpression of μ- and δ-opioid receptors decreases the binding of their selective agonists (Jordan and Devi, 1999; George et al., 2000). In contrast to the individually expressed μ- and δ-opioid receptors, the co-expressed receptors are insensitive to pertussis toxin in COS cells (George et al., 2000). Furthermore, the μ-opioid agonist [D-Ala2,N-Me-Phe4,Gly-ol5]-enkephalin (DAMGO) inhibits spontaneous [Ca2+]i oscillations in a cell line expressing only μ-opioid receptors. However, in the same cell line expressing both δ- and μ-opioid receptors, DAMGO produces an excitatory effect characterized by an increase in both the baseline [Ca2+]i and the frequency of [Ca2+]i oscillations (Charles et al., 2003). Importantly, morphine tolerance does not develop in either δ-opioid receptor-1 or preproenkephalin knockout mice (Nitsche et al., 2002). Hence, it is possible that increased surface expression of δ-opioid receptors may negatively influence the analgesic effects of μ-opioid agonists.

2.3. Effect of opioid receptor agonists on ion channels

The μ-, δ-, κ-, and ORL1 opioid receptor agonists inhibit neuronal activity through (1) inhibition of VGCCs in the DRG neurons (Moises et al., 1994a; Acosta and Lopez, 1999; Beedle et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2004), and (2) suppression of neuronal excitability through activation of GIRK channels in the postsynaptic neurons in the spinal cord (Schneider et al., 1998; Marker et al., 2006).

High voltage-gated Ca2+ channels are located at presynaptic terminals and soma of primary sensory neurons that synapse in the spinal dorsal horn. Activation of μ-, δ-, κ-, and ORL1-opioid receptors inhibits VGCCs in dissociated DRG neurons (Moises et al., 1994a; Moises et al., 1994b; Acosta and Lopez, 1999; Beedle et al., 2004). For example, both morphine and DAMGO have been demonstrated to selectively inhibit N-type and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels in DRG neurons (Schroeder et al., 1991; Schroeder and McCleskey, 1993; Wu et al., 2004). Also, application of δ-opioid agonists inhibits high voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in primary sensory neurons (Acosta and Lopez, 1999). In DRG neurons, μ-opioid receptor agonists have a greater effect on high voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (including N-type, P/Q-type, L-type, and R-type) in IB4 (a commonly used marker for unmyelinated afferent fibers)-negative than in IB4-positive DRG neurons (Wu et al., 2004). By contrast, low voltage-gated (T-type) Ca2+ channels are rarely modulated by DAMGO and nociceptin in DRG neurons (Beedle et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2004).

Opioid receptor agonists inhibit N-type Ca2+ channels through both voltage-dependent and voltage-independent means (Tedford and Zamponi, 2006). The inhibition of Ca2+ currents by opioid agonists is blocked by pertussis toxin, suggesting the involvement of Gi/o proteins (Morikawa et al., 1995; Su et al., 1998; Larsson et al., 2000; Raingo et al., 2007). Importantly, this Gi/o protein-dependent inhibition of high voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in nociceptors is controlled by genetic diversity in N-type Ca2+ channels (Raingo et al., 2007). Exons 37a and 37b are a pair of mutually exclusive exons encoding two alternative 32-amino-acid modules (e[37a] and e[37b], respectively) at the C-terminus of CaV2.2. Nociceptive neurons express a unique CaV2.2 splice isoform containing exon 37a (Bell et al., 2004). Opioid agonists inhibit CaV2.2 e[37a] in a voltage-independent manner through a Gαi/o-GTP-tyrosine kinase pathway (Raingo et al., 2007). The voltage-dependent inhibition of CaV2.2 e[37b] is mediated by Gβγ liberated from Gi/o proteins and can be relieved by a strong membrane depolarization (Raingo et al., 2007). It has been reported that ORL1-opioid receptors form a unique partnership with CaV2.2 channels in a subset of sensory neurons, a phenomenon not observed with any other opioid receptors (Beedle et al., 2004). In addition to the tonic inhibition of high voltage-gated Ca2+ channels mediated by Gi/o proteins, Ca2+ channels may be inhibited by another mechanism: prolonged exposure of DRG neurons to nociceptin, the agonist of ORL1-opioid receptors, may stimulate Gq/11 proteins and trigger protein kinase C-dependent internalization of the ORL1-CaV2.2 complex (Altier et al., 2006), thereby downregulating the activity of Ca2+ channels.

Activation of μ-opioid receptors with DAMGO causes significant hyperpolarization of spinal superficial dorsal horn neurons through activation of GIRK channels (Schneider et al., 1998; Marker et al., 2006). It has been demonstrated that GIRK1 and GIRK2 are coexpressed with μ-opioid receptors in a subset of lamina II excitatory neurons (Marker et al., 2005; Marker et al., 2006). Genetic ablation or pharmacologic inhibition of spinal GIRK channels attenuates the dose-dependent analgesic effect of DAMGO and the δ-opioid agonist DPDPE (Marker et al., 2005). Intrathecal administration of tertiapin-Q, a blocker of GIRK channels, reduces the analgesic effect of morphine in a tail flick test (Marker et al., 2004). In GIRK1 and GIRK2 knockout mice, the antinociceptive effect of intrathecally administered morphine is attenuated (Mitrovic et al., 2003; Marker et al., 2004), and this inhibition correlates with a dramatic reduction in the expression of both GIRK subunits in the spinal superficial dorsal horn (Marker et al., 2004). Also, reduction in the antinociceptive effect of the κ-opioid receptor agonist U50,488H has been reported in mice with a mutation in the pore-forming region of the GIRK2 subunit (Ikeda et al., 2000).

2.4. Effect of opioid receptor agonists on synaptic transmission

The spinal dorsal horn is critically involved in pain transmission and is a major site for opioid analgesic effect (Dickenson, 1995; Light and Willcockson, 1999; Chen and Pan, 2006a). Both the μ- and δ-opioid agonists produce dose-dependent inhibition of C-fiber-evoked firing activity of dorsal horn neurons in response to noxious stimuli (Dickenson et al., 1987; Sullivan et al., 1989). Activation of μ-opioid and δ-opioid receptors profoundly inhibits glutamate release from the primary afferent terminals to spinal dorsal horn neurons (Kohno et al., 1999). Also, the substance P release evoked by stimulation of dorsal root C-fiber afferents is diminished by DAMGO and decreased by DPDPE (Kondo et al., 2005).

Some of the analgesic actions of μ-opioids may be due to modulation of the descending pathways to reduce nociceptive transmission in the spinal dorsal horn (Basbaum and Fields, 1984). For example, activation of presynaptic μ-opioid receptors primarily attenuates GABAergic synaptic input in the amygdala (Finnegan et al., 2005; Finnegan et al., 2006). Opioids also reduce synaptic GABA release to spinally projecting neurons in the rostral ventromedial medulla (Finnegan et al., 2004) and periaqueductal gray (Vaughan et al., 1997). Furthermore, through presynaptic inhibition of GABA release, activation of δ-opioid receptors may disinhibit spinally projecting noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus (Pan et al., 2002a).

It should be noted that μ-, δ-, and κ-opioid receptor agonists at nanomolar concentrations prolong the action potentials in some DRG neurons (Shen and Crain, 1989). Stimulation of opioid receptors can increase Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ stores in different cell lines via activation of phospholipase C (Spencer et al., 1997; Chan et al., 2000). Coactivation of Gq and Gi/o may be required for this opioid excitatory effect (Chan et al., 2000). The functional outcome of this effect is not clear but it may play a role in opioid-induced hyperalgesia.

3. Cannabinoid receptors

Two cannabinoid receptor subtypes, CB1 and CB2, have been identified. CB1 receptors are expressed mainly on neurons in the central and peripheral nervous systems (Tsou et al., 1998; Hohmann et al., 1999; Farquhar-Smith et al., 2000; Salio et al., 2002b). In contrast, CB2 receptors are expressed mainly on immune cells (Munro et al., 1993; Facci et al., 1995). Both receptors are coupled to the Gi/o family of G proteins and inhibit adenylyl cyclase in most tissues and cells (Howlett et al., 1986).

3.1. Distribution of cannabinoid receptors in pain pathways

CB1 receptors have been identified in DRG neurons (Hohmann et al., 1999; Ross et al., 2001; Ahluwalia et al., 2002). CB1 receptor mRNA and proteins are highly expressed in a subpopulation of rat DRG neurons, especially in medium- and large-sized neurons (Bridges et al., 2003). CB1 receptor mRNA is also expressed in trigeminal ganglion neurons, mainly those of medium and large diameter (Price et al., 2003). Peripheral tissue inflammation increases the ratio of CB1-positive to CB1-negative DRG neurons, primarily in C-fiber nociceptors (Amaya et al., 2006). Nerve injury increases CB1 receptor mRNA and proteins in the DRG neurons (Walczak et al., 2005; Mitrirattanakul et al., 2006).

CB1 receptor-like immunoreactivity is found in the dorsolateral funiculus, the superficial dorsal horn (laminae I and II), and lamina X (Farquhar-Smith et al., 2000). Capsaicin treatment in neonatal rats produces a minimal change in CB1 receptor binding sites in the spinal cord (Hohmann and Herkenham, 1998). However, in rats subjected to rhizotomy, about 50% of CB1 receptors are lost in the spinal dorsal horn (Hohmann and Herkenham, 1999). These findings indicate that most CB1 receptors are located on non-TRPV1-expressing primary afferent neurons and their central terminals in the spinal cord. CB1 receptors are also expressed in numerous astrocytes in laminae I and II of the spinal dorsal horn (Salio et al., 2002a). Nerve injury induces the upregulation of spinal CB1 receptors primarily within the ipsilateral superficial dorsal horn (Lim et al., 2003; Walczak et al., 2005).

There seems to be little or no CB2 receptor-like immunoreactivity in normal DRG neurons (Wotherspoon et al., 2005) and in spinal cord tissue (Zhang et al., 2003; Wotherspoon et al., 2005). Notably, sciatic nerve injury, but not tissue inflammation, induces CB2 receptor mRNA expression in the ipsilateral dorsal horn of the spinal cord (Zhang et al., 2003). Upregulation of CB2 receptor mRNA and proteins in the DRG and spinal cord is also found in animals subjected to spinal nerve ligation (Wotherspoon et al., 2005; Beltramo et al., 2006) or saphenous nerve ligation (Walczak et al., 2005; Walczak et al., 2006).

3.2. Antinociceptive effect of cannabinoid receptor agonists

Intrathecal administration of the non-selective cannabinoid receptor agonist anandamide blocks the thermal hyperalgesia caused by carrageenan injection into the rat hindpaw (Richardson et al., 1998a). Similarly, intrathecal administration of another non-selective cannabinoid receptor agonist, WIN55,212-2, reverses the mechanical allodynia or hyperalgesia induced by injection of complete Freund's adjuvant into the rat hindpaw (Martin et al., 1999) or partial ligation of the sciatic nerve (Fox et al., 2001). Systemic administration of WIN55,212-2 suppresses nociceptive behaviors in the formalin test (Tsou et al., 1996) and thermal and mechanical hyperalgesia induced by intradermal injection of capsaicin, an agonist of nociceptive TRPV1 receptors, through CB1 receptors (Li et al., 1999). WIN55,212-2 also produces antihyperalgesic and antiallodynic effects in chronic pain caused by peripheral nerve injury (Herzberg et al., 1997; Bridges et al., 2001).

CB1 receptors expressed in the peripheral nerves and the DRG neurons play an important role in the antinociceptive effect of WIN55,212-2 (Agarwal et al., 2007). Intraplantar administration of WIN55,212-2 attenuates the development of carrageenan-evoked mechanical hyperalgesia and allodynia (Nackley et al., 2003) and capsaicin-evoked thermal hyperalgesia (Johanek et al., 2001). Intraplantar administration of anandamide also produces antinociception in the formalin test (Calignano et al., 1998). Peripheral administration of the CB1 receptor agonist arachidonyl-2-choroethylamide (ACEA) produces a potent inhibitory effect on the response of spinal dorsal horn neurons to innocuous and noxious stimuli in rats with hindpaw inflammation (Kelly et al., 2003).

Systemic administration of the selective CB2 receptor agonist, HU308, attenuates nociception induced by formalin injection in rats (Hanus et al., 1999). Intraplantar and systemic administration of another CB2 agonist, AM1241, reduces thermal nociception (Malan et al., 2001). Additionally, systemic injection of GW405833, another selective CB2 agonist, produces antihyperalgesic effects in rodent models of neuropathic and inflammatory pain (Valenzano et al., 2005).

In patients with chronic neuropathic pain, the non-selective CB receptor agonist, CT-3, has potent antiallodynic and analgesic effects (Karst et al., 2003). Cannabis-based medicinal extracts significantly reduce neuropathic pain in patients (Berman et al., 2004). Cannabis also effectively reduces neuropathic pain in patients with HIV-associated sensory neuropathy (Woolridge et al., 2005; Abrams et al., 2007). A single oral dose of cannabis extract (Cannador) can provide adequate postoperative pain relief (Holdcroft et al., 2006).

Some studies suggest that endogenous cannabinoids are important for nociceptive regulation at the spinal and peripheral levels. For instance, intrathecal administration of the CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716A or antisense knockdown of spinal CB1 receptors produce thermal hyperalgesia (Richardson et al., 1998b; Dogrul et al., 2002). Spinal administration of SR141716A selectively facilitates the C-fiber-mediated nociceptive responses of dorsal horn neurons in rats (Chapman, 1999). In addition, SR141716A and the CB2 antagonist SR144528 prolong and enhance the pain behavior produced by tissue damage (Calignano et al., 1998). However, the hyperalgesic effects of SR141716A are not observed in inflammation (Beaulieu et al., 2000; Harris et al., 2000) or neuropathic pain models (Bridges et al., 2001). Also, the nociceptive threshold of wild-type and CB1 receptor knockout mice is not significantly different (Ledent et al., 1999).

3.3. Effect of cannabinoid receptor agonists on ion channels

CB1 receptor activation inhibits N-type, P/Q-type, and R-type VGCCs in cultured neurons and cell lines (Mackie and Hille, 1992; Twitchell et al., 1997; Brown et al., 2004). Stimulation of CB1 receptors seems to solely inhibit N-type VGCCs in rat large DRG neurons (Khasabova et al., 2004). The CB1 receptor agonists CP55,940 and ACEA inhibit the increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration evoked by depolarization or capsaicin (Khasabova et al., 2004; Sagar et al., 2005), and this effect is limited primarily to medium- and large-sized DRG neurons (Khasabova et al., 2004). Furthermore, CB1 agonists activate GIRK channels expressed in cell lines (Mackie et al., 1995) and sympathetic neurons (Guo and Ikeda, 2004). The antinociceptive effect of WIN55,212-2 is reduced in GIRK2 knockout mice (Blednov et al., 2003), suggesting that the analgesic action of cannabinoid receptor agonists is at least partially dependent on their effect on GIRK channels.

The effect of CB2 agonists on ion channels in the nociceptive neurons is little known. The CB2 receptor agonist, JWH-133, inhibits capsaicin-evoked calcium responses in DRG neurons in neuropathic and sham-operated rats (Sagar et al., 2005). In transfected cell lines, CB2 receptors are not coupled to either Q-type VGCCs or GIRK channels (Felder et al., 1995).

3.4. Effect of cannabinoid receptor agonists on synaptic transmission

The CB1 receptor agonist ACEA inhibits C-fiber-evoked responses in spinal dorsal horn neurons in normal and inflammatory pain models (Kelly and Chapman, 2001; Khasabova et al., 2004). Spinal administration of the non-selective cannabinoid receptor agonist HU210 reduces the C-fiber mediated response of spinal dorsal horn neurons only in spinal nerve-injured rats (Kelly and Chapman, 2001). However, for reducing Aδ-fiber-evoked responses, HU210 is effective in both sham-operated and nerve-injured rats (Chapman, 2001). In the spinal cord, the synaptic transmission between primary afferent neurons and dorsal horn neurons is inhibited by activation of CB1 receptors. In this regard, WIN55,212-2 reduces glutamate release from primary afferents, and this effect is blocked by the CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716A (Morisset and Urban, 2001). Furthermore, anandamide is more effective in inhibiting Aδ-fiber-mediated than C-fiber-mediated glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the spinal dorsal horn (Luo et al., 2002). However, WIN55,212-2 seems to have a greater effect on C-fiber- than Aδ-fiber-mediated excitatory synaptic transmission in the trigeminal synapses (Liang et al., 2004). Additionally, WIN55,212-2 inhibits both GABAergic and glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the rat periaqueductal gray (Vaughan et al., 2000) and the mouse amygdala (Azad et al., 2003).

Intraplantar injection of the CB2 receptor agonist JWH-133 significantly inhibits evoked responses of spinal dorsal horn neurons in rat models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain (Elmes et al., 2004). Spinal application of JWH-133 also attenuates responses of spinal dorsal neurons to mechanical stimuli in neuropathic, but not sham-operated, rats (Khasabova et al., 2004). Application of other CB2 receptor agonists, such as L768242 and AM1241, reduces capsaicin-mediated calcitonin gene-related peptide release in rat spinal cord slices (Beltramo et al., 2006). These results suggest that peripheral and spinal CB2 receptors may be an important analgesic target.

4. α2-Adrenergic receptors

The α2-adrenergic receptors are widely distributed in the peripheral and central nervous systems. Three α2-adrenergic receptor subtypes have been cloned (α2A, α2B, and α2C), all of which are coupled to pertussis-toxin-sensitive Gi/o proteins (Bylund et al., 1992).

4.1. Distribution of α2-adrenergic receptors in pain pathways

The locus coeruleus is the largest noradrenergic cell group in the brain (Probst et al., 1984). Activation of the α2-adrenergic receptors in the locus coeruleus causes hypnosis. The spinal dorsal horn is an important site for the relay and modulation of nociceptive transmission by the α2-adrenergic receptors. Both the α2A- and α2C-adrenergic receptors are expressed in the spinal dorsal horn and the DRG neurons (Sullivan et al., 1987; Stone et al., 1997; Stone et al., 1998). The mRNA of all three α2-adrenergic receptor subtypes is expressed in the human spinal cord and DRG (Smith et al., 1995; Ongioco et al., 2000). However, very little mRNA of the α2B-adrenergic receptors is detected in the rat spinal dorsal horn (Shi et al., 1999). Capsaicin treatment in neonatal rats or resiniferatoxin treatment in adult rats removes TRPV1-expressing sensory neurons and induces a large decrease in the α2A-, but not the α2C-, adrenergic receptor immunoreactivity in the spinal dorsal horn (Stone et al., 1998; Chen et al., 2007a). These findings suggest that the α2A-adrenergic receptor is located primarily on the central terminals of primary afferent neurons, while the α2C subtype is located primarily on the spinal dorsal horn neurons (Stone et al., 1998; Chen et al., 2007a). Peripheral nerve injury decreases the α2A-, but not α2C-, adrenergic receptor immunoreactivity in the rat spinal cord ipsilateral to the injury side (Stone et al., 1999).

4.2. Antinociceptive effect of α2-adrenergic receptor agonists

The commonly used selective α2-adrenergic receptor agonists include clonidine, dexmedetomidine, guanabenz, and UK14,303. The α2-adrenergic agonists produce analgesic effects when given parenterally, epidurally, or intrathecally in humans (Rauck et al., 1993; Eisenach et al., 1995; De Kock et al., 1997a; De Kock et al., 1997b). Because the spinal cord likely is the major site of the analgesic action of clonidine, the epidural and intrathecal routes have been considered preferable to the intravenous route (Eisenach et al., 1993; Eisenach et al., 1995; Yaksh et al., 1995). There is no convincing evidence showing that supraspinal sites are involved in the analgesic action of α2-adrenergic receptor agonists administered spinally and systemically. Currently, clonidine remains the only α2-adrenergic receptor agonist for epidural and intrathecal use. Dexmedetomidine is used systemically to treat postoperative pain in patients (Alhashemi and Kaki, 2004; Wahlander et al., 2005).

Intrathecal administration of clonidine or dexmedetomidine produces an analgesic effect on acute nociception (Buerkle and Yaksh, 1998; Chen et al., 2007a). Interestingly, intrathecal injection of clonidine has a potent effect on thermal nociception but only a small and short-lasting effect on the mechanical nociceptive threshold in rats (Chen et al., 2007a). Furthermore, the α2-adrenergic receptor agonists are effective in alleviating tactile allodynia associated with chronic neuropathic pain in rats (Yaksh et al., 1995; Pan et al., 1999). In the hot-plate test, the antinociceptive effect of the α2-adrenergic receptor agonist UK14,304 in mice is abolished by the α2A-preferring receptor antagonists RX821002 or BRL44408 (Millan, 1992). Using α2A-, α2B-, and α2C-subtype knockout mice, it has been shown that the α2A-adrenergic receptors are primarily involved in the analgesic effect produced by α2-adrenergic receptor agonists (Stone et al., 1997; Fairbanks et al., 2002; Mansikka et al., 2004). Furthermore, the α2C, but not α2B-, adrenergic receptors in the spinal cord contribute to the antinociceptive effect produced by intrathecal injection of an imidazoline/α2-adrenergic receptor agonist, moxonidine (Fairbanks et al., 2002). These studies demonstrate that α2A- and α2C-adrenergic receptors are probably essential for the antinociceptive effect induced by α2-adrenergic receptor agonists.

4.3. Effect of α2-adrenergic receptor agonists on ion channels

α2-Adrenergic receptor agonists can hyperpolarize the neurons in the locus coeruleus (Aghajanian and VanderMaelen, 1982). Although the effect of α2-adrenergic agonists on the ion channels has not been specifically studied in the DRG neurons, these agents can inhibit depolarization-induced Ca2+ influx in these neurons (Attali et al., 1991). In the locus coeruleus neurons, α2-adrenergic receptor agonists inhibit VGCCs (Ingram et al., 1997). Stimulation of α2-adrenergic receptors inhibits the N-type Ca2+ channels in the sympathetic neurons (Lipscombe et al., 1989). Furthermore, α2-adrenergic receptor agonists induce a GIRK current in the hypothalamic neurons (Li and van den Pol, 2005). In mice lacking the GIRK2 channel subunit, the antinociceptive effect of clonidine is reduced (Mitrovic et al., 2003). These findings suggest that GIRK channels contribute to the inhibitory effect of α2-adrenergic receptor agonists on nociceptive transmission.

4.4. Effect of α2-adrenergic receptor agonists on synaptic transmission

Electrophysiological studies using rat spinal cord slices have demonstrated that clonidine can inhibit synaptic glutamate release from primary afferent nerves to spinal dorsal horn neurons (Pan et al., 2002b). Clonidine also significantly reduces capsaicin-evoked glutamate release from the primary afferent nerves (Ueda et al., 1995). This evidence supports the notion that presynaptic α2-adrenergic receptors play an important role in the regulation of the glutamatergic synaptic input to spinal dorsal horn neurons, which could contribute to the analgesic actions produced by α2-adrenergic receptor agonists (Pan et al., 2002b). Interestingly, removal of α2A-adrenergic receptors on TRPV1-expressing afferent neurons paradoxically potentiates the antinociceptive effect produced by intrathecal injection of clonidine in rats (Chen et al., 2007a). This finding suggests that α2A-adrenergic receptors or other subtypes expressed on non-TRPV1-expressing sensory neurons and spinal dorsal horn neurons are more important than such receptors expressed on TRPV1-expressing afferent neurons for the analgesic action of α2-adrenergic receptor agonists. Additionally, it has been suggested that the antinociceptive effect of α2-adrenergic receptor agonists may be due in part to acetylcholine release in the spinal cord (Klimscha et al., 1997; Pan et al., 1999). However, the mechanisms and circuitry involved in this action are not fully known.

5. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors

Molecular cloning studies have revealed five molecularly distinct muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs) referred to as M1-M5 (Caulfield, 1993; Wess et al., 2003). The odd-numbered subtypes are selectively linked to Gq/11 proteins to activate phospholipase C, while the even-numbered subtypes are selectively coupled to the pertussis toxin-sensitive Gi/o proteins (Caulfield, 1993; Fields and Casey, 1997; Caulfield and Birdsall, 1998; Wess et al., 2003).

5.1. Distribution of mAChRs in pain pathways

The mAChRs are widely expressed throughout the central and peripheral nervous systems (Caulfield, 1993; Levey, 1993; Vilaro et al., 1993). In the rat DRG, there is a high level of expression of M2 mRNA, and much lower levels of M3 and M4 mRNA are also detected (Tata et al., 2000). All three of these subtypes are preferentially localized in medium- and small-sized DRG neurons. These findings suggest the possible involvement of the M2, M3, and M4 subtypes in the modulation of nociceptive transduction. The M2 subtype is also present on peripheral nerve endings of sensory neurons but absent on fibers labeled with Substance P immunoreactivity (Haberberger and Bodenbenner, 2000). There is no convincing evidence for the presence of M1 and M5 subtypes in rat DRG neurons (Tata et al., 2000).

In the rat spinal cord, radioligand binding studies suggest that M2, M3, and M4, but not M1, mAChR subtypes are present in the superficial dorsal horn (Hoglund and Baghdoyan, 1997). Strong M2 immunoreactivity is located in laminae I-III of the rat and mouse spinal cord (Duttaroy et al., 2002; Li et al., 2002). Using mAChR subtype knockout mice, it has been shown that the M2 subtype is abundant in the superficial laminae of the dorsal horn, where the M4 subtype is expressed only at a low level (Duttaroy et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2005a). Interestingly, [35S]GTPγS binding data suggest that the functional activity of spinal M4 receptors is dependent on the presence of the M2 subtype, possibly indicating the existence of functional M2/M4 mAChR oligomers in the spinal cord (Chen et al., 2005a). The mAChRs, especially the M2 subtype, are upregulated in the dorsal spinal cord in diabetic rats, which accounts for increased analgesic efficacy of mAChR agonists in diabetic neuropathic pain (Chen and Pan, 2003c). Upregulation of the M2 subtype in small- and medium-sized DRG neurons has also been reported in rats with nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain (Hayashida et al., 2006).

5.2. Antinociceptive effect of mAChR agonists

One of the physiological functions of the mAChRs is to tonically regulate nociceptive transmission in the spinal cord. In this regard, blockade of mAChRs with atropine in the spinal cord causes a large decrease in the nociceptive threshold in rats (Zhuo and Gebhart, 1991). Intrathecal administration of mAChR agonists or acetylcholinesterase inhibitors produces a potent analgesic effect in rats, mice, and humans (Naguib and Yaksh, 1994; Hood et al., 1997; Ellis et al., 1999; Duttaroy et al., 2002; Chen and Pan, 2003c), and this analgesic effect is blocked by atropine (Naguib and Yaksh, 1994). The mAChRs also mediate some of the antinociceptive effects of opioids (Chen and Pan, 2001) and can enhance the analgesic effect of systemic opioids in humans (Hood et al., 1997). Furthermore, behavioral studies have shown that mAChRs are involved in the antinociceptive effect of the α2-adrenergic agonist clonidine (Pan et al., 1999).

The lack of highly selective mAChR agonists and antagonists has largely hindered efforts to delineate the mAChR subtypes involved in the analgesic effect of mAChR agonists. But recently, the use of mAChR subtype knockout mice has clearly shown that the M2 and M4 subtypes are mainly responsible (Gomeza et al., 1999; Duttaroy et al., 2002). Also, activation of the M2 subtype present on cutaneous nociceptors can suppress the transduction of nociceptive information (Bernardini et al., 2002). In a rat model of diabetic neuropathic pain, the antinociceptive effect produced by intrathecal administration of mAChR agonists is largely potentiated by upregulation of the M2 subtype in the spinal dorsal horn (Chen and Pan, 2003c).

5.3. Effect of mAChR agonists on ion channels

In rat sensory neurons, activation of mAChRs inhibits high voltage-gated Ca2+ channels through pertussis toxin-sensitive Gi/o proteins, probably mediated by the M2 or M4 subtype (Wanke et al., 1994). In mouse sympathetic neurons, the role of mAChR subtypes in the modulation of N-type, P/Q-type, and L-type Ca2+ channels has been determined by using mAChR subtype knockout mice. The M2 subtype mediates fast, voltage-dependent inhibition of N-type and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels, but the M4 subtype does not affect the Ca2+ channels in mouse sympathetic neurons (Shapiro et al., 1999; Shapiro et al., 2001).

Stimulation of the M2 mAChR subtype can activate GIRK channels in the sympathetic and hippocampal CA1 neurons (Fernandez-Fernandez et al., 1999; Seeger and Alzheimer, 2001). Notably, application of mAChR agonists to the sympathetic neurons inhibits a voltage-activated K+ current termed the “M current” or KCNQ channel current (Brown and Adams, 1980). Because the channels underlying the current are activated near the resting membrane potential, inhibition of these channels results in a small membrane depolarization and a decrease in membrane conductance. KCNQ channels are also present in nociceptive sensory neurons and play an important role in controlling the excitability of nociceptors (Passmore et al., 2003). Stimulation of KCNQ channels with retigabine not only inhibits C- and Aδ-fiber-mediated responses of dorsal horn neurons evoked by natural or electrical afferent stimulation but also inhibits the responses of dorsal horn neurons to carrageenan in rats (Passmore et al., 2003).

5.4. Effect of mAChR agonists on synaptic transmission

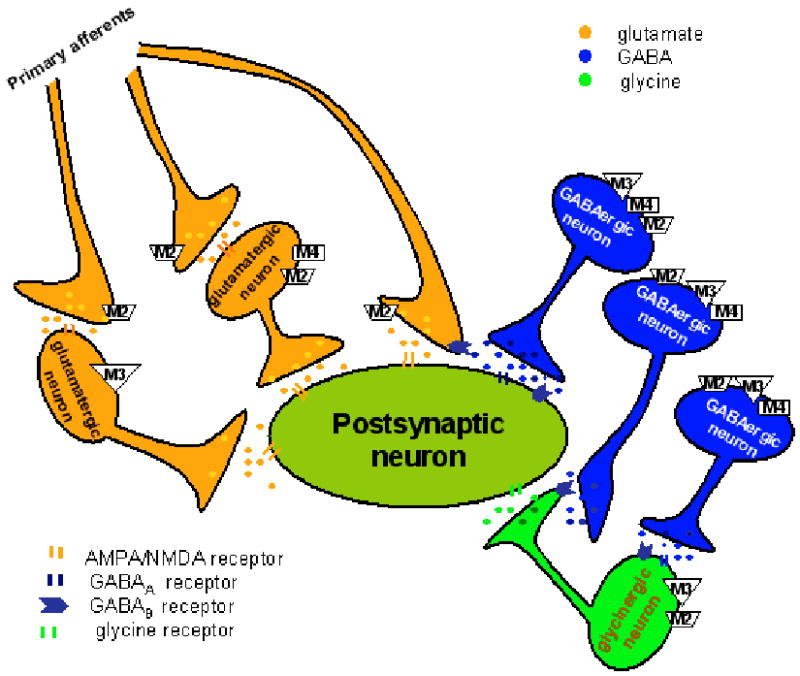

Activation of mAChRs inhibits the response of spinal dorsal horn projection neurons to nociceptive stimuli in rats (Chen and Pan, 2004). The antinociceptive effects produced by mAChR agonists are likely due to their combined effects of increasing the inhibitory GABA and glycine release and decreasing the excitatory glutamate release in the spinal dorsal horn (Li et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2007). The mAChR subtypes involved in the inhibition of glutamate release in the dorsal horn have been determined by using a combination of mAChR subtype-preferring antagonists and pertussis toxin treatment in rat spinal cord slices (Zhang et al., 2007). The M2 subtype plays a critical role in the inhibitory effect of mAChR agonists on glutamatergic input from primary afferents to spinal dorsal horn neurons (Figure 1). The M3 and M4 subtypes, possibly located in a subpopulation of glutamatergic interneurons, also contribute to the inhibitory effect of mAChR agonists on glutamatergic transmission in the rat spinal dorsal horn (Zhang et al., 2007).

Figure 1.

Schematic depicting the distribution and interaction between primary afferent terminals and interneurons in the rat spinal dorsal horn upon stimulation of the three mAChR subtypes. Activation of the M2 subtype on the primary afferent terminals and M3 and M2/M4 subtypes on a subpopulation of interneurons inhibit glutamatergic input to dorsal horn neurons. Stimulation of M2, M3, and M4 subtypes on the somatodendritic site of GABAergic interneurons can potentiate synaptic GABA release. Furthermore, the M2 and M3 subtypes present on the somatodendritic site of glycinergic interneurons are responsible for increased glycinergic input to spinal dorsal horn neurons upon activation of mAChRs. Additionally, concurrent stimulation of mAChRs on adjacent GABAergic interneurons can attenuate glycinergic and glutamatergic input to spinal dorsal horn neurons through GABA spillover and activation of presynaptic GABAB receptors.

In the rat spinal cord, the M2, M3, and M4 subtypes are all involved in the potentiation of GABAergic input to lamina II neurons (Zhang et al., 2005), and the M3 subtype is mainly responsible for the potentiating effect of mAChR agonists on glycinergic input to spinal lamina II neurons in rats (Figure 1) (Wang et al., 2006). However, the mAChR agonists primarily inhibit GABAergic and glycinergic synaptic transmission in the spinal dorsal horn of wild-type mice (Zhang et al., 2006a; Zhang et al., 2006b). Further investigations using mAChR subtype knockout mice have revealed that activation of the M2 and M4 subtypes inhibits spinal GABA and glycine release. In contrast, stimulation of the M3 subtype potentiates both GABAergic and glycinergic input to dorsal horn neurons in mice (Zhang et al., 2006a; Zhang et al., 2006b). It is not yet clear how reduction in GABA and glycine synaptic release by spinal M2 and M4 subtypes contributes to the analgesic effect of mAChR agonists in mice. Because the lamina II neurons are likely interneurons, it is possible that this reduction in GABA and glycine synaptic release may lead to disinhibition of inhibitory neurons in the spinal dorsal horn to reduce nociceptive transmission in mice. Furthermore, glycine is a co-agonist for the glycine binding site of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. Decreased synaptic glycine release may reduce nociceptive transmission by decreasing the NMDA receptor activity in the spinal dorsal horn.

Studies on the role of mAChRs in the control of synaptic transmission have revealed that synaptic GABA and glycine release is differentially regulated in the spinal dorsal horn. In this regard, stimulation of mAChRs leads to increased GABA release, which attenuates synaptic glycine release through GABAB receptors (Zhang et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2006). Therefore, there is a complex dynamic interaction between GABAergic and glycinergic interneurons through GABAB receptors upon activation of mAChRs in the spinal cord.

6. GABAB receptors

GABA is the most important inhibitory neurotransmitter and is widely distributed throughout the central nervous system. GABA activates three pharmacologically distinct types of receptors: ionotropic GABAA and GABAC receptors and G protein-coupled GABAB receptors (Bowery, 1993; Bowery and Enna, 2000). Numerous GABAB receptor subunit isoforms have been identified. Initial studies indicated that fully functional GABAB receptors must be composed of a GABAB1 and a GABAB2 protein (Jones et al., 1998; Kaupmann et al., 1998; Bowery and Enna, 2000; Chronwall et al., 2001). However, more recent findings suggest that GABAB1 alone or GABAB1 homodimers may display some activity as well (Gassmann et al., 2004).

6.1. Distribution of GABAB receptors in pain pathways

GABAB receptors are present in the primary afferent neurons, spinal cord, and brain (Price et al., 1987; Chu et al., 1990; Towers et al., 2000). GABAB receptor immunoreactivities are distributed in the laminae I-III in the spinal cord and in DRG neurons (Price et al., 1984; Price et al., 1987; Towers et al., 2000), consistent with data showing high density of binding sites for the GABAB agonist baclofen in these areas (Gehlert et al., 1985). Also, the mRNA of all three GABAB subunits is expressed in both the spinal cord and DRG (Towers et al., 2000). In the DRG, more that 90% of the GABAB1 subunit mRNA is GABAB1a; less than 10% is GABAB1b (Towers et al., 2000). The function of GABAB receptors is critically determined by the subunits, particularly the GABAB1a subunit (Towers et al., 2000; Gassmann et al., 2004; Vigot et al., 2006). Primary afferent fiber degeneration by capsaicin administration in neonatal rats decreases GABAB receptor density by 50% (Price et al., 1984; Price et al., 1987), suggesting that at least this proportion of GABAB receptors is present on TRPV1-expressing primary afferent terminals. In the brain, GABAB receptor binding sites are present in the thalamus, amygdala, periaqueductal gray, parabrachial nucleus, and medullary raphe nucleus (Chu et al., 1990).

Nerve injury may alter the expression of GABAB receptors in the spinal cord. For example, sciatic nerve axotomy causes a large reduction in GABAB mRNA levels in the spinal cord (Castro-Lopes et al., 1995; Yang et al., 2004). However, the immunoreactivity of GABAB receptors is not significantly altered in the spinal cord after ligation of the L5 spinal nerve in rats (Engle et al., 2006). It is has been reported that in rats subjected to nerve ligation, although the antinociceptive effect of baclofen is increased, there is no significant difference in the density and binding affinity of spinal GABAB receptors (Smith et al., 1994).

6.2. Antinociceptive effect of GABAB receptor agonists

The GABAB receptor agonist baclofen has long been known to produce an antinociceptive effect in animal models of acute pain upon intrathecal administration (Hammond and Drower, 1984; Dirig and Yaksh, 1995; Stefani et al., 1998). In chronic neuropathic pain induced by peripheral nerve injury and diabetic neuropathy in rats, baclofen exhibits an antinociceptive effect (Smith et al., 1994; Malcangio and Tomlinson, 1998). Baclofen is mainly used spinally to treat chronic pain in patients with spasticity (Plassat et al., 2004; Slonimski et al., 2004). Intrathecal administration of baclofen has been used as an adjuvant analgesic to treat patients with neuropathic pain (Fromm, 1994; Slonimski et al., 2004). Furthermore, intrathecal infusion of baclofen can reduce pain caused by stroke or spinal cord injury and musculoskeletal pain (Taira et al., 1994; Loubser and Akman, 1996; Becker et al., 2000).

6.3. Effect of GABAB receptor agonists on ion channels

Activation of GABAB receptors reduces high voltage-gated Ca2+ channel activity mainly in cultured newborn rat DRG neurons (Dolphin and Scott, 1986; Menon-Johansson et al., 1993). It has been shown that baclofen inhibits the VGCCs by slowing the activation phase of the current without affecting T-type Ca2+ channels (Tatebayashi and Ogata, 1992). Because prior blockade of N-type Ca2+ channels with ω-conotoxin-GVIA completely occludes baclofen-induced inhibition of VGCCs, the N-type Ca2+ current appears to be mainly responsible for the inhibition of VGCCs by baclofen. Application of GABA or baclofen shortens the DRG action potential duration by decreasing an N-type Ca2+ current (Green and Cottrell, 1988). Reduction in GABAB1 receptor subunit with antisense oligodeoxynucleotide substantially attenuates the inhibitory effect of baclofen on VGCCs, indicating that the GABAB1 subunit contributes to baclofen-induced inhibition of VGCCs in DRG neurons (Hand et al., 2000).

In the rat small-diameter trigeminal ganglion neurons, baclofen inhibits neuronal excitability through potentiation of voltage-dependent K+ currents (Takeda et al., 2004). Stimulation of GABAB receptors can activate GIRK channels in the hippocampal neurons (Luscher et al., 1997; Jarolimek et al., 1998). Modulation of K+ conductances appears to be primarily linked to post-synaptic GABAB receptors (Luscher et al., 1997). In the spinal dorsal horn, baclofen activates a GIRK channel current in lamina II neurons (Marker et al., 2006).

6.4. Effect of GABAB receptor agonists on synaptic transmission

The spinal dorsal horn contains both excitatory and inhibitory interneurons involved in the modulation of nociceptive information from primary afferent nerves. Glutamate is an important excitatory neurotransmitter released from central terminals of primary afferent neurons, while GABA and glycine are the two important inhibitory neurotransmitters in the spinal cord. Inhibition of the release of glutamate and neuropeptides from primary afferents by activation of presynaptic GABAB receptors likely contributes to the antinociceptive effect of baclofen (Ataka et al., 2000; Iyadomi et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2007). In this regard, baclofen dose-dependently decreases the glutamate release from the primary afferent terminals in rat spinal cord slices (Ataka et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2007). Baclofen has a greater effect on C-fiber- than Aδ-fiber-evoked glutamate release in the spinal cord, suggesting that GABAB receptors may be preferentially expressed on C-fiber as opposed to Aδ-fiber afferent terminals (Ataka et al., 2000). The function of presynaptic GABAB receptors on the primary afferent terminals, but not on GABAergic and glycinergic interneurons, is significantly reduced in diabetic neuropathy (Wang et al., 2007). This is consistent with a study showing that the analgesic effect of baclofen is reduced in diabetic rats (Malcangio and Tomlinson, 1998).

GABAB receptors are also involved in the inhibitory effect of acetylcholine on spinal glutamatergic synaptic transmission. Blockade of GABAB receptors attenuates the inhibition of ascending dorsal horn neurons produced by mAChR agonists and the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor neostigmine (Chen and Pan, 2004). Thus, activation of GABAB receptors contributes to the antinociceptive effect of intrathecally administered mAChR agonists or neostigmine (Li et al., 2002; Chen and Pan, 2003b; Chen and Pan, 2004). Increased GABA release after activation of mAChRs could spill over sufficiently to activate presynaptic GABAB receptors on the neighboring glutamatergic terminals to indirectly inhibit glutamate release (Li et al., 2002). In addition to reducing glutamatergic synaptic transmission, GABAB receptor activation attenuates GABA and glycine release in the spinal dorsal horn (Iyadomi et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2007).

7. Group II and III metabotropic glutamate receptors

The actions of glutamate are mediated by two receptor families: ionotropic glutamate receptors and metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs). Ionotropic glutamate receptors are classified into three broad subtypes: α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid, kainate, and NMDA. Eight mGluRs (mGluR1-mGluR8) have been cloned and are classified into three groups on the basis of similarities in their amino acid sequences, their linkage to second messenger systems, and their pharmacology (Conn and Pin, 1997). Group I mGluRs (mGluRs 1 and 5) couple to phospholipase C, signal through inositol phospholipid breakdown, and generally increase neuronal firing and synaptic transmission. In contrast, stimulation of group II mGluRs (mGluRs 2 and 3) and group III mGluRs (mGluRs 4, 6, 7, and 8) inhibits adenylyl cyclase and generally reduces neuronal excitability and synaptic transmission (Conn and Pin, 1997; Macek et al., 1998; Schoepp et al., 1999). Thus, group I mGluR antagonists and group II and III mGluR agonists generally produce antinociceptive effects. In this section, we review the role of group II and group III mGluRs in the control of pain transmission.

7.1. Distribution of group II and III mGluRs in pain pathways

All three groups of mGluRs are distributed throughout the central nervous system, and the mGluRs are involved in various forms of neuroplasticity (Conn and Pin, 1997). The group II mGluRs (mGluR2/3) are present at the afferent terminals in the spinal superficial dorsal horn (Jia et al., 1999; Tang and Sim, 1999; Carlton et al., 2001b). Immunoreactivity for mGluR2/3 is also located in the DRG neurons (Petralia et al., 1996; Carlton et al., 2001b). Approximately 40% of L4 and L5 DRG neurons contain mGluR2/3-like immunoreactivity. These mGluR2/3-positive cells are small in diameter, and 76% of them contain IB4; conversely, 67% of IB4 cells have mGluR2/3-like immunoreactivity (Carlton et al., 2001b).

Two subtypes of group III mGluRs, mGluR4 and mGluR7, are located in the spinal dorsal horn. mRNA and immunoreactivity for mGluR4 and mGluR7 have been found in the superficial dorsal horn, especially laminae I and II (Ohishi et al., 1995a; Li et al., 1997; Azkue et al., 2001). Interestingly, group II and III mGluRs may be segregated in the superficial dorsal horn: group II mGluRs seem to be in the inner zone of lamina II, but group III mGluRs are mainly in lamina I and the outer zone of lamina II (Ohishi et al., 1995b; Li et al., 1997; Jia et al., 1999; Tang and Sim, 1999). Intense expression of both mGluR4 and mGluR7 mRNA also has been detected in the DRG (Ohishi et al., 1995a). Immunocytochemistry studies have shown that mGluR7 is primarily located in small-diameter DRG neurons (Ohishi et al., 1995b). Peripheral nerve injury reduces group II and III mGluRs in the spinal dorsal horn (unpublished data), which may contribute to an increase in excitatory glutamatergic input to dorsal horn neurons and central sensitization in chronic neuropathic pain.

7.2. Antinociceptive effect of group II and III mGluR agonists

The antinociceptive effect of group II and III mGluR agonists has been studied only in animal models of acute and chronic pain. The group II mGluR agonist LY354740 and the group III mGluR agonist L-(+)-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyric acid (L-AP4) can reverse the sensitization of spinal dorsal horn neurons induced by intradermal capsaicin injection in primates (Neugebauer et al., 2000). Pretreatment with the selective group II mGluR agonist (2R,4R)-4-aminopyrrolidine-2,4- dicarboxylate or the group III mGluR agonist L-AP4 reduces the development of neuropathic pain in rats (Fisher et al., 2002). Although intrathecal administration of L-AP4 has no significant effect on normal nociception, it reduces tactile allodynia induced by spinal nerve ligation in rats (Chen and Pan, 2005).

7.3. Effect of group II and III mGluR agonists on ion channels

L-AP4 inhibits N-type and P/Q-type VGCCs in cortical pyramidal neurons (Stefani et al., 1998) and inhibits N-type VGCCs in rat sympathetic neurons (Guo and Ikeda, 2005). In cultured cerebellar granule neurons, stimulation of mGluR7 blocks P/Q-type VGCCs (Perroy et al., 2000). Presynaptic group III mGluRs seem to be coupled primarily to N-type Ca2+ channels in the hippocampal neurons (Capogna, 2004). However, only P/Q-type Ca2+ channels mediate group III mGluR inhibition at the calyx of Held synapse (Takahashi et al., 1996). Furthermore, activation of groups II and III mGluRs causes neuronal hyperpolarization through GIRK channels (Dutar et al., 1999). The group II mGluR agonist LY354740 can activate GIRK channels in rat cerebellar neurons (Knoflach and Kemp, 1998). The effect of group II and III mGluR agonists on VGCCs and GIRK channels has not been specifically determined in nociceptive neurons in the DRG and spinal dorsal horn.

7.4. Effect of group II and III metabotropic glutamate receptor agonists on synaptic transmission

Group II and III mGluRs are primarily located on presynaptic terminals, where they function primarily as autoreceptors to provide feedback regulation of glutamate release (Pin and Duvoisin, 1995; Conn and Pin, 1997). Activation of group II and III mGluRs also inhibits glutamatergic transmission in many brain regions and in the normal spinal cord (Jane et al., 1996; Conn and Pin, 1997; Gerber et al., 2000). Activation of group II and III mGluRs attenuates the firing activity of spinal dorsal horn neurons in acute and chronic pain models (Neugebauer et al., 2000; Chen and Pan, 2005). Some group II and III mGluRs are also localized on the GABAergic interneurons and terminals in the spinal cord (Jia et al., 1999), and group II and III mGluR agonists decrease synaptic GABA release in normal spinal cord slices (Gerber et al., 2000). Notably, it is the integration of excitatory and inhibitory inputs that shapes the output of nociceptive signals in the spinal dorsal horn. Thus, the concurrent effect of group II and III mGluR agonists on both glutamatergic and GABAergic input to spinal dorsal horn neurons probably explains the lack of net effect of L-AP4 on dorsal horn neurons and nociception in normal animals (Chen and Pan, 2005). In nerve-injured animals, it is the primary inhibitory effect on glutamatergic transmission that likely accounts for the antiallodynic effect of the group II or III mGluR agonists (Chen and Pan, 2005). It is possible that activation of group II and III mGluRs, particularly mGluR3 and mGluR7, primarily reduces glutamate release in the spinal cord in neuropathic pain conditions.

Group III mGluRs inhibit glutamate release mainly through a calmodulin-Ca2+ channel-dependent mechanism. Mutations interfering with calmodulin binding and calmodulin antagonists both inhibit G protein-mediated modulation of Ca2+ channels by mGluR7 (O'Connor et al., 1999). The signaling mechanisms responsible for the inhibitory effect of presynaptic group II and III mGluRs on synaptic transmission in the spinal cord are not known at present. In addition to exerting an inhibitory effect on glutamate release from the primary afferents (Gerber et al., 2000), group II and III mGluRs play an important role in the regulation of GABAergic synaptic transmission in the spinal cord when the nociceptive primary afferents are stimulated with capsaicin (Zhou et al., 2007). In about 50% of lamina II neurons, increased nociceptive inflow reduces synaptic GABA release through activation of presynaptic group II and III mGluRs in spinal cord slices (Zhou et al., 2007). Thus, group II and III mGluRs are actively involved in the modulation of pain transmission in the spinal cord.

8. Somatostatin receptors

Somatostatin (SST) was originally described as a hypothalamic polypeptide that inhibits the secretion of pituitary growth hormone. It is a 14-amino-acid disulfide bridge-containing peptide (SST-14). There is also another bioactive form of somatostatin, the 28 amino-acid SST-28, generated from the same preprosomatostatin precursor as SST-14. Both forms are primarily produced by neural and secretory cells and are widely distributed in the central and peripheral nervous systems.

SST produces its effect by binding to SST receptors (SSTRs), a family of GPCRs. Five distinct subtypes of SSTRs (SSTR1-5) and two isoforms of SSTR2 (SSTR2a and SSTR2b) have been identified and characterized in humans and other species (Hoyer et al., 1994; Hoyer et al., 1995). The SSTRs are heterogeneously expressed and coupled to pertussis toxin-sensitive and -insensitive G proteins to activate multiple intracellular effector pathways. SSTRs can interact through homo- and hetero-oligomerization with other SSTR family members or with members of other families of GPCRs (Rocheville et al., 2000; Olias et al., 2004). All of the SSTRs contribute to the diverse and complex SST actions.

8.1. Distribution of SSTRs in pain pathways

SST immunoreactivity is present in some primary sensory neurons (Hokfelt et al., 1976; Tessler et al., 1986). SST-containing neurons are also found in the trigeminal sensory nucleus (Lazarov and Chouchkov, 1990). SSTR1-4, but not SSTR5, mRNA has been found in the DRG neurons (Bar et al., 2004). Approximately 60% of SSTR2a-immunoreactive DRG neurons are positive for TRPV1, and approximately 33% of TRPV1-immunoreactive DRG neurons are positive for SSTR2a (Carlton et al., 2004). SSTR2b receptor-like immunoreactivity is identified in the vast majority of DRG neurons, and SSTR4 is present in 40% of DRG neurons and some satellite cells (Bar et al., 2004).

In the spinal dorsal horn, SST-containing neurons are predominantly localized in laminae I, II and III (Mizukawa et al., 1988; Segond von Banchet et al., 1999), particularly at the levels of the cervical and lumbar spinal cord (Yin, 1995). About 13% of lamina I and 15% of lamina II neurons express SSTR2a receptors (Todd et al., 1998). These data provide the cellular and molecular basis for the role of SST in the modulation of pain transmission. Nerve injury can cause a reduction in SST-containing neurons in the spinal dorsal horn (Swamydas et al., 2004). However, peripheral nerve ligation has no effects on the expression of SST and preprosomatostatin mRNA (Dong et al., 2005). In a rat model of arthritis, SSTR2a receptor-like immunoreactivity in the DRG neurons is significantly reduced, but the SSTR2a mRNA expression level is not altered (Bar et al., 2004).

8.2. Antinociceptive effect of somatostatin receptor agonists

Most experimental studies demonstrate that SST has an antinociceptive effect. Intrathecal injection of SST can increase the nociceptive threshold (Chapman and Dickenson, 1992; Ono et al., 1997). Peripheral (local) application of SST and SST analogues also produces analgesic effects. For example, intraplantar injection of the SST analogue octreotide reduces formalin-induced nociceptive behaviors and the responses of C-fibers to noxious stimulation (Carlton et al., 2001a; Carlton et al., 2003). Intraplantar injection of SCR007, a selective non-peptide SSTR2 agonist, significantly increases the nociceptive threshold (Ji et al., 2006). TT-232, an SST analogue with the highest binding affinity for SSTR4, also inhibits formalin-induced nociception and reduces allodynia in diabetic neuropathy (Szolcsanyi et al., 2004). J-2156, another selective SSTR4 agonist, inhibits nociceptive behavior in the second phase of the formalin test in mice and decreases inflammation-induced allodynia and nerve injury-induced hyperalgesia in rats (Sandor et al., 2006). Thus, both SSTR2 and SSTR4 are promising analgesic targets.

SST is effective in the treatment of patients with certain pain conditions, including cluster headache (Sicuteri et al., 1984), headache associated with pituitary tumors (Williams et al., 1986), and postoperative pain (Taura et al., 1994). Spinal administration of SST or octreotide reduces pain in patients with terminal cancer (Mollenholt et al., 1994).

8.3. Effect of SSTR agonists on ion channels

SST inhibits VGCCs in a subpopulation of DRG neurons (Polo-Parada and Pilar, 1999). In sympathetic and amygdaloid neurons, SST inhibits high voltage Ca2+ channels including the N-type (Golard and Siegelbaum, 1993; Shapiro and Hille, 1993) and P/Q-type (Viana and Hille, 1996) Ca2+ channels, but has little or no effect on the T-type Ca2+ channels (Viana and Hille, 1996). SST inhibition of VGCCs is mediated by pertussis toxin-sensitive Gi/o proteins or through a second pathway involving a cGMP-dependent protein kinase (Shapiro and Hille, 1993; Meriney et al., 1994).

SST-28 can activate GIRK channels while SST-14 suppresses a voltage-dependent, non-inactivating K+ current in the sympathetic ganglion neurons (Kurenny et al., 1992). Activation of GIRK channels by SST in the murine brain is inhibited by anti-Gαi1/Gαi2 antibody (Takano et al., 1997). In dissociated rat spinal cord neurons, SST can inhibit VGCCs (Sah, 1990). Intraplantar injection of octreotide reduces capsaicin-induced pain behaviors in rats, suggesting that SST may inhibit TRPV1 channels expressed on primary afferent nerves (Carlton et al., 2004).

8.4. Effect of SSTR agonists on synaptic transmission

SST decreases the responses of spinal dorsal horn neurons to the noxious heat stimulus in vivo (Sandkuhler et al., 1990). Although the effect of SSTR agonists on neurotransmitter release has not been examined in the nociceptive pathway, SST reduces both GABA and glutamate release in basal forebrain neurons (Momiyama and Zaborszky, 2006). In the CA1 region of the hippocampus, SST inhibits glutamate but not GABA release (Tallent and Siggins, 1997). SST depresses the postsynaptic membrane excitability of spinal lamina II neurons by activating pertussis toxin-sensitive GIRK channels (Kim et al., 2002; Jiang et al., 2003). These electrophysiological studies suggest that inhibition of nociceptive transmission is an important mechanism underlying the analgesic effect of SSTR agonists.

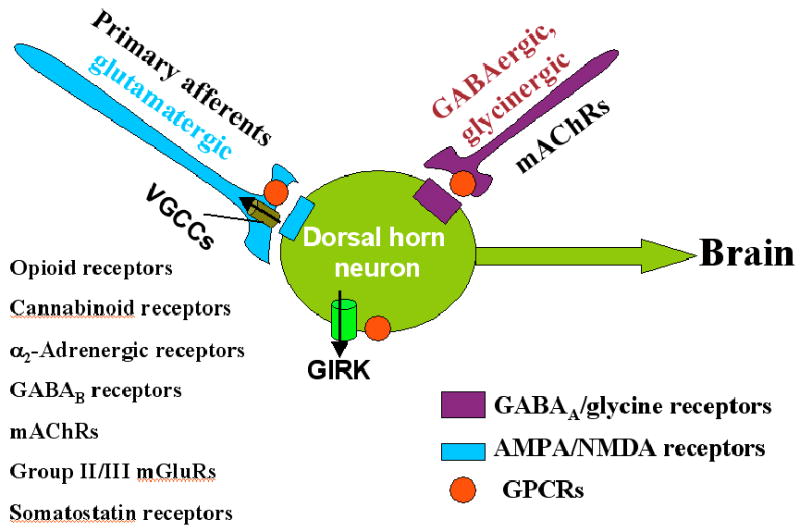

9. Concluding remarks

Much progress has been made in the past 10 years in the understanding of important roles of various GPCRs in the regulation of pain transmission. As summarized in Figure 2, the analgesic effects of GPCR agonists are primarily due to inhibition of presynaptic VGCCs on primary afferent neurons and activation of postsynaptic GIRK channels on postsynaptic dorsal horn neurons in the spinal cord. These two actions constitute the major pharmacologic basis for the analgesic effect of GPCR agonists discussed in this review. However, intracellular signaling is a very complex and diverse process, and many important questions remain about the precise signal transduction mechanisms (e.g., G protein subtypes, regulatory molecules, and downstream effectors) that underlie the diverse effects of individual GPCR agonists on ion channels and synaptic transmission in the pain pathway. Furthermore, many GPCRs are capable of forming different dimer combinations and interact with G proteins to affect diverse intracellular signaling pathways and various ion channels. GPCR heteromerization and regulatory proteins, such as regulator of G protein-signaling proteins, are involved in the expression and function of GPCRs. Further studies on the signal transduction pathways and molecular interactions between GPCR proteins in the nociceptive neurons are essential for a better understanding of the analgesic actions of drugs acting on GPCRs. Development of subtype-specific agents for each GPCR likely will improve the efficacy and minimize the side effects of GPCR analgesics used to treat acute and chronic pain.

Figure 2.

Schematic drawing showing the site and effectors of GPCRs in the modulation of pain transmission at the spinal cord level. Activation of GPCRs listed on the left inhibits VGCCs on the presynaptic terminal of primary afferents to reduce glutamate release. These GPCRs also activate GIRK channels on postsynaptic dorsal horn neurons to hyperpolarize the neuron. Additionally, stimulation of mAChRs potentiates the synaptic release of GABA and glycine from inhibitory interneurons to decrease the excitability of dorsal horn neurons that project to the brain. Together, these effects account for the analgesic effects of the agonists of these GPCRs. GIRK, G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K+ channels; GPCRs, G protein-coupled receptors; mAChRs, muscarinic acetylcholine receptors; mGluRs, metabotropic glutamate receptors; VGCCs, voltage-gated Ca2+ channels.

Acknowledgments

Work conducted in the authors' laboratory was supported by grants GM64830 and NS45602 from the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- DAMGO

[D-Ala2,N-Me-Phe4,Gly-ol5]-enkephalin

- DPDPE

[D-Pen2,D-Pen5]-enkephalin

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- GIRK

G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K+ channels

- GPCRs

G protein-coupled receptors

- mAChRs

muscarinic acetylcholine receptors

- mGluRs

metabotropic glutamate receptors

- ORL1

opioid receptor-like 1

- SST

somatostatin

- VGCCs

voltage-gated Ca2+ channels

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abrams DI, Jay CA, Shade SB, Vizoso H, Reda H, Press S, et al. Cannabis in painful HIV-associated sensory neuropathy: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2007;68:515–521. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000253187.66183.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acosta CG, Lopez HS. delta opioid receptor modulation of several voltage-dependent Ca(2+) currents in rat sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8337–8348. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-08337.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal N, Pacher P, Tegeder I, Amaya F, Constantin CE, Brenner GJ, et al. Cannabinoids mediate analgesia largely via peripheral type 1 cannabinoid receptors in nociceptors. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:870–879. doi: 10.1038/nn1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghajanian GK, VanderMaelen CP. alpha 2-adrenoceptor-mediated hyperpolarization of locus coeruleus neurons: intracellular studies in vivo. Science. 1982;215:1394–1396. doi: 10.1126/science.6278591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahluwalia J, Urban L, Bevan S, Capogna M, Nagy I. Cannabinoid 1 receptors are expressed by nerve growth factor- and glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor-responsive primary sensory neurones. Neuroscience. 2002;110:747–753. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00601-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhashemi JA, Kaki AM. Dexmedetomidine in combination with morphine PCA provides superior analgesia for shockwave lithotripsy. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:342–347. doi: 10.1007/BF03018237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altier C, Khosravani H, Evans RM, Hameed S, Peloquin JB, Vartian BA, et al. ORL1 receptor-mediated internalization of N-type calcium channels. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:31–40. doi: 10.1038/nn1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaya F, Shimosato G, Kawasaki Y, Hashimoto S, Tanaka Y, Ji RR, et al. Induction of CB1 cannabinoid receptor by inflammation in primary afferent neurons facilitates antihyperalgesic effect of peripheral CB1 agonist. Pain. 2006;124:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arner S, Meyerson BA. Lack of analgesic effect of opioids on neuropathic and idiopathic forms of pain. Pain. 1988;33:11–23. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90198-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ataka T, Kumamoto E, Shimoji K, Yoshimura M. Baclofen inhibits more effectively C-afferent than Adelta-afferent glutamatergic transmission in substantia gelatinosa neurons of adult rat spinal cord slices. Pain. 2000;86:273–282. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00255-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attali B, Nah SY, Vogel Z. Phorbol ester pretreatment desensitizes the inhibition of Ca2+ channels induced by kappa-opiate, alpha 2-adrenergic, and muscarinic receptor agonists. J Neurochem. 1991;57:1803–1806. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb06384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azad SC, Eder M, Marsicano G, Lutz B, Zieglgansberger W, Rammes G. Activation of the cannabinoid receptor type 1 decreases glutamatergic and GABAergic synaptic transmission in the lateral amygdala of the mouse. Learn Mem. 2003;10:116–128. doi: 10.1101/lm.53303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azkue JJ, Murga M, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Mateos JM, Elezgarai I, Benitez R, et al. Immunoreactivity for the group III metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype mGluR4a in the superficial laminae of the rat spinal dorsal horn. J Comp Neurol. 2001;430:448–457. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20010219)430:4<448::aid-cne1042>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar KJ, Schurigt U, Scholze A, Segond Von Banchet G, Stopfel N, Brauer R, et al. The expression and localization of somatostatin receptors in dorsal root ganglion neurons of normal and monoarthritic rats. Neuroscience. 2004;127:197–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basbaum AI, Fields HL. Endogenous pain control systems: brainstem spinal pathways and endorphin circuitry. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1984;7:309–338. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.07.030184.001521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu P, Bisogno T, Punwar S, Farquhar-Smith WP, Ambrosino G, Di Marzo V, et al. Role of the endogenous cannabinoid system in the formalin test of persistent pain in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;396:85–92. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00226-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker R, Benes L, Sure U, Hellwig D, Bertalanffy H. Intrathecal baclofen alleviates autonomic dysfunction in severe brain injury. J Clin Neurosci. 2000;7:316–319. doi: 10.1054/jocn.1999.0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beedle AM, McRory JE, Poirot O, Doering CJ, Altier C, Barrere C, et al. Agonist-independent modulation of N-type calcium channels by ORL1 receptors. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:118–125. doi: 10.1038/nn1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell TJ, Thaler C, Castiglioni AJ, Helton TD, Lipscombe D. Cell-specific alternative splicing increases calcium channel current density in the pain pathway. Neuron. 2004;41:127–138. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00801-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltramo M, Bernardini N, Bertorelli R, Campanella M, Nicolussi E, Fredduzzi S, et al. CB2 receptor-mediated antihyperalgesia: possible direct involvement of neural mechanisms. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:1530–1538. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman JS, Symonds C, Birch R. Efficacy of two cannabis based medicinal extracts for relief of central neuropathic pain from brachial plexus avulsion: results of a randomised controlled trial. Pain. 2004;112:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardini N, Roza C, Sauer SK, Gomeza J, Wess J, Reeh PW. Muscarinic M2 receptors on peripheral nerve endings: a molecular target of antinociception. J Neurosci. 2002;22:RC229. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-12-j0002.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blednov YA, Stoffel M, Alva H, Harris RA. A pervasive mechanism for analgesia: activation of GIRK2 channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:277–282. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012682399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowery NG. GABAB receptor pharmacology. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1993;33:109–147. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.33.040193.000545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowery NG, Enna SJ. gamma-aminobutyric acid(B) receptors: first of the functional metabotropic heterodimers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;292:2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges D, Ahmad K, Rice AS. The synthetic cannabinoid WIN55,212-2 attenuates hyperalgesia and allodynia in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133:586–594. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges D, Rice AS, Egertova M, Elphick MR, Winter J, Michael GJ. Localisation of cannabinoid receptor 1 in rat dorsal root ganglion using in situ hybridisation and immunohistochemistry. Neuroscience. 2003;119:803–812. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA, Adams PR. Muscarinic suppression of a novel voltage-sensitive K+ current in a vertebrate neurone. Nature. 1980;283:673–676. doi: 10.1038/283673a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SP, Safo PK, Regehr WG. Endocannabinoids inhibit transmission at granule cell to Purkinje cell synapses by modulating three types of presynaptic calcium channels. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5623–5631. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0918-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buerkle H, Yaksh TL. Pharmacological evidence for different alpha 2-adrenergic receptor sites mediating analgesia and sedation in the rat. Br J Anaesth. 1998;81:208–215. doi: 10.1093/bja/81.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylund DB, Blaxall HS, Iversen LJ, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ, Lomasney JW. Pharmacological characteristics of alpha 2-adrenergic receptors: comparison of pharmacologically defined subtypes with subtypes identified by molecular cloning. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;42:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calignano A, La Rana G, Giuffrida A, Piomelli D. Control of pain initiation by endogenous cannabinoids. Nature. 1998;394:277–281. doi: 10.1038/28393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capogna M. Distinct properties of presynaptic group II and III metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated inhibition of perforant pathway-CA1 EPSCs. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:2847–2858. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]