Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the involvement of SPARC (secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine) mutations and copy number variation in juvenile-onset primary open-angle glaucoma (JPOAG).

Methods

This study involved the 27 family members from the GLC1M (glaucoma 1, open angle, M)-linked Philippine pedigree with JPOAG, 46 unrelated Chinese patients with JPOAG and 95 controls. Mutation screening of the SPARC sequence, covering the promoter, 5′-untranslated region (UTR), entire coding regions, exon-intron boundaries, and part of the 3′-UTR, was performed using polymerase chain reaction and direct DNA sequencing. Copy number of the gene was analyzed by three TaqMan copy number assays.

Results

No putative SPARC mutation was detected in the Philippine family. In the Chinese participants, 11 sequence variants were detected. Two were novel: IVS2+8G>T and IVS2+32C>T. For the 9 known SNPs, one was synonymous (rs2304052, p.Glu22Glu) and the others were located in noncoding regions. No individual SNP was associated with JPOAG. Five of the most common SNPs, i.e., rs2116780, rs1978707, rs7719521, rs729853, and rs1053411, were contained in a LD (linkage disequilibrium) block. Haplotype-based analysis showed that no haplotype was associated with the disorder. Copy number analysis revealed that all study subjects had two copies of the gene, suggesting no correlation between the copy number of SPARC and JPOAG.

Conclusions

We have excluded SPARC as the causal gene at the GLC1M locus in the Philippine pedigree and, for the first time, revealed that the coding sequences, splice sites and copy number of SPARC do not contribute to JPOAG. Further investigations are warranted to unravel the involvement of SPARC in the pathogenesis of other forms of glaucoma.

Introduction

Glaucoma is a group of degenerative optic neuropathies involving progressive loss of retinal ganglion cells and their axons, resulting in a characteristic pattern of optic nerve head and visual field damage [1,2]. It is the leading cause of irreversible blindness globally [3]. Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG), characterized by a gonioscopically open anterior chamber angle, is a leading form of glaucoma in many populations [4-6].

POAG has complex etiology. It could be monogenic, e.g., myocilin glaucoma, or multifactorial, resulting from additive or interactive effects of environmental and genetic factors. Intraocular pressure (IOP) is a major risk factor. Accordingly, POAG has been divided into high-tension (HTG, IOP>21 mmHg) and normal-tension (NTG, IOP≤21 mmHg) entities, and it is considered a spectrum of disease reflecting different susceptibilities to a given IOP level [7]. The trabecular meshwork (TM) provides the major resistance to aqueous humor outflow in cases in which IOP is elevated [1,2]. Thus, genetic and/or other factors affecting IOP, outflow facility, and retinal ganglion cell viability may play important roles in POAG susceptibility.

To date, more than 20 linkage loci have been mapped for POAG [8-24]. However, only three genes, i.e., myocilin (MYOC, GLC1A) [25], optineurin (OPTN, GLC1E) [26], and WD repeat domain 36 (WDR36, GLC1G) [18], were identified. These genes account for less than 10% of overall POAG [27-30]. Causal genes in the rest of the loci and genes independent of the linkage loci remain to be identified. Candidate genes for POAG can be prioritized by at least six criteria: (1) expressed in eye tissues; (2) involved in IOP regulation; (3) affecting ganglion cell viability; (4) associated with other eye or retinal diseases; (5) associated with other neurodegenerative diseases; and (6) located at reported linkage loci.

In this study, we evaluated SPARC (secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine, OMIM 182120) as a candidate gene for JPOAG. The SPARC gene is located at chromosomal region 5q31.3-q32 within the GLC1M locus (5q22.1–32; OMIM 610535) mapped by our group [20]. SPARC, also known as osteonectin or BM-40, is a matricellular glycoprotein that functions primarily to promote extracellular matrix deposition [31]. It is expressed at high levels in bone tissues and is distributed widely in many other tissues and cell types [32]. In human eyes, SPARC is found in lens [33], corneal epithelium [33], TM cells [34,35], and retinal pigment epithelium [33,36,37]. It distributes throughout the trabecular meshwork and is prominent in the juxtacanalicular region [35]. In the trabecular meshwork of postmortem human eyes, SPARC and another glaucoma gene MYOC responded significantly to elevated-IOP [38]. SPARC is one of the most highly upregulated genes in porcine TM cells in response to mechanical stretching [39], supporting an important role of SPARC in IOP regulation [35]. Furthermore, elevated expression of SPARC has been detected in the iris of POAG patients [40], although whether such change was a cause or consequence of glaucoma, or just a phenomenon secondary to the use of topical medications for glaucoma remained unverified. Recently, the SPARC null mouse has been shown to have lower IOP than the wild-type, likely due to decreased outflow resistance. Moreover, heterozygous mice expressed an intermediate phenotype suggestive of a dose-dependent effect of SPARC [41]. These findings suggest that SPARC could be implicated in POAG, likely by compromising the regulation of IOP.

No study has yet evaluated the involvement of SPARC mutations in human glaucoma. If any kind of SPARC variations are associated with or causative for POAG, at least 5 possibilities should be considered: (1) promoter polymorphisms that affect the expression level of the gene; (2) missense variants with gain (or loss)-of-function; (3) nonsense mutations leading to loss-of-function; (4) variants at the exon-intron boundaries causing alternative splicing; and (5) copy number variants that may alter gene dosage. In view of the finding that SPARC null mice have lower IOPs [41], it is likely additional copies of SPARC may correlate with higher IOP. Moreover, as the GLC1M locus was identified in a pedigree of juvenile-onset primary open-angle glaucoma (JPOAG) with high IOP [20], we investigated the involvement of SPARC variants in JPOAG by mutation screening and copy number analysis.

Methods

Participants

The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee for Human Research, the Chinese University of Hong Kong. All procedures adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from every participant after explanation of the nature of the study.

The Philippine pedigree with JPOAG has been described in detail previously [20,42]. Briefly, this five-generation family comprised 95 members, with 22 being affected. Peripheral venous blood was collected from 27 members, who underwent complete ophthalmic examinations, and of whom 9 were affected. JPOAG was defined based on the following criteria: (1) exclusion of secondary causes, e.g., trauma, uveitis, steroid-induced or exfoliation glaucoma; (2) gonioscopically open anterior chamber angle, Shaffer grade III or IV; (3) IOP≥22 mmHg in the affected eye measured by applanation tonometry; (4) characteristic optic disc damage and/or typical visual field loss by Humphrey automated perimetry using the Glaucoma Hemifield test; and (5) age at diagnosis ≤40 years. For the affected subjects, the age at diagnosis ranged from 12 to 33 years (mean±SD: 19±4.2 years), the highest recorded IOP was between 24 and 44 mmHg (32±6.3 mmHg), vertical cup-disc ratio (VCDR) ranged from 0.7 to 0.9 (median: 0.8), and visual field loss was compatible with glaucoma in two consecutive tests. The unaffected members aged from 3 to 73 years (25±19.9 years) at study recruitment, with IOP <22 mmHg, VCDR between 0.2 and 0.5 (median: 0.3), and the visual field within normal range.

Unrelated Chinese subjects were recruited from the eye clinics of Hong Kong Eye Hospital. We enrolled 46 patients with sporadic JPOAG and 95 controls (characteristics shown in Table 1). They were given complete ophthalmic examinations and were diagnosed using the same criteria described above. Of the patients, age at diagnosis ranged from 6 to 40 years conforming to JPOAG. The highest recorded IOP in the more severely affected eye was between 23 and 69 mmHg and the VCDR 0.5–0.9. Control subjects were recruited from participants aged ≥60 years who visited the clinics for senile cataract, itchy eyes or floaters. They were confirmed to be free of glaucoma or other major eye diseases. Their IOP was <21 mmHg, with both VCDR and visual field within normal range. As SPARC has been implicated in systemic conditions, subjects with known systemic diseases, such as tumor, diabetes, etc., were not included.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of Chinese JPOAG and control subjects.

| |

|

|

Age at diagnosis (years) |

IOP (mmHg)* |

VCDR* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Sample size | Female (%) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range | Median | Range | Median |

| JPOAG |

46 |

19 (41.3) |

6–40 |

24.8 (8.5) |

23–69 |

30 |

0.5–0.9 |

0.8 |

| Control | 95 | 40 (42.1) | 61–94 | 75.1 (7.1) | 10–21 | 15 | 0.2–0.5 | 0.3 |

The asterisk indicates that the IOP value is the recorded highest IOP, and the vertical cup/disc ratio (VCDR) is the measure at the latest follow-up visit before study enrollment.

Gene screening and copy number analysis of SPARC

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA concentration was measured by a ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). The target sequences, including part of the promoter (−1 to −318 bp upstream of the transcription initiation site), 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR, +1 to +314 bp downstream of the transcription initiation site), the entire coding regions (c.1 to c.912), exon-intron junctions, and part of the 3′-UTR (c.912+1 to c.912+94), were screened in the 27 members of the Philippine pedigree, 46 Chinese patients and 95 Chinese controls. Primer sequences were designed using Primer3 [43] (v.0.4.0) referring to the published gene sequence of SPARC (ENSG00000113140) in Ensembl [44] (Table 2). The target sequences were amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and analyzed by direct DNA sequencing using the dye-termination chemistry (Big-Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Reaction Kit; ver. 3.1; Applied Biosystems, Inc. [ABI], Foster City, CA) on an automated sequencer (3130XL; ABI), according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Table 2. Primer sequences and PCR conditions for SPARC sequencing.

| |

Primer sequence |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplifying target | Forward primer (5′→3′) | Reverse primer (5′→3′) | MgCl2 (mM) | Ta (°C) | Size (bp) |

| SPARC-1 (promoter + exon 1) |

CCAGTTCCAAATCATCAAGGA |

GGGGTTGGTGCAACTATAGAA |

1.5 |

59 |

668 |

| SPARC-2 (exon 2) |

AAATGGAACCAACCTCCTCA |

CAATGGTCCTCATCCCAGTT |

1.5 |

60 |

388 |

| SPARC-3 (exon 3) |

AGCTCCCCTAGCCTGTATCC |

CCCTAATTTCTCAGGGCACA |

1.5 |

60 |

225 |

| SPARC-4 (exon 4) |

CTTTCCCTAACACCCCTGGT |

TCATGTAGGCTGTCCTCGTG |

1.5 |

60 |

367 |

| SPARC-5 (exon 5) |

TGTGCTAGTCCAGGTGATGC |

TGTATTCCGAAGTGCCCAAT |

1.5 |

60 |

222 |

| SPARC-6 (exon 6) |

CAGTGTCCCCATCTCTGAAA |

CCCAAGACAGGAGTCTGGAA |

1.5 |

60 |

250 |

| SPARC-7 (exon 7) |

AAGAAACTGTGGCCTGGAGA |

CTGGTGCTCAGGGGTAAATG |

1.5 |

60 |

396 |

| SPARC-8 (exon 8) |

CTGGCTAGTCTCTGCCTGCT |

TCACTCTAGGGTCTGGGGTCT |

2.0 |

60 |

279 |

| SPARC-9 (exon 9) |

GGGTGTGGAGCTTTTCCAT |

CCCCTTGCTTCTTTGTTCAG |

1.5 |

60 |

229 |

| SPARC-10 (exon 10) | TCCACTGACTCCTTGGGAAG | GGCAGAACAACAAACCATCC | 1.5 | 60 | 198 |

The promoter (−1 to −318 bp from the transcription initiation site), 5′-untranslated region (the noncoding exon 1), coding regions, exon-intron boundaries, and a portion of the 3′-untranslated region (+1 to +94 bp downstream the stop codon) were covered by the amplimers. In the table, Ta indicates annealing temperature and Bp indicates base pairs.

Copy number analysis of SPARC was performed for all the 27 subjects from the pedigree, 18 randomly selected Chinese JPOAG patients (10 females) and 18 controls (9 females), using the TaqMan® Copy Number Assays (Applied Biosystems). Three assays were selected for this purpose (Table 3), with one being located in proximity to the 5′-end of the SPARC gene, one near the 3′-end, and one within the gene. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, the DNA samples were diluted to a concentration of 5 ng/μl. Each PCR reaction mix contained 5.0 μl of 2× TaqMan® Genotyping Master Mix, 0.5 μl of the TaqMan Copy Number target assay, 0.5 μl of the TaqMan Copy Number reference assay (RNase P), which is known to exist only in two copies in a diploid genome, 2.0 μl of Nuclease-free water, and 2.0 μl of DNA. The reactions were processed in an ABI 7900HT Fast real time PCR System using a 384-well reaction plate, with each DNA sample analyzed in duplicates and on 95 °C/10 min for 1 cycle followed by 92 °C/ 15 s and 60 °C/1 min for 40 cycles. Data was collected by the SDS software (version 2.3; ABI) using the standard absolute quantification method. After the reaction, raw data was analyzed using a manual cycle threshold (CT) of 0.2 with the automatic baseline on, and then imported to the CopyCallerTM Software (version 1.0; ABI) for post-PCR data analysis. In the software, copy numbers were estimated using a maximum likelihood algorithm. The analytical setting was the same for the three assays.

Table 3. TaqMan® Copy Number Assays used for copy number analysis of SPARC.

| Assay ID | Reporter dye | Context sequence | Location on NCBI assembly |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hs02667978_cn |

FAM |

GTCTCAAAACCCCAGCTCAAAATAC |

151021358 |

| Hs06106867_cn |

FAM |

GTCAGAAGGTTGTTGTCCTCATCCC |

151027253 |

| Hs06124887_cn | FAM | CTTCCCAGAGGTGTGGATTAATGGT | 151046100 |

The three assays selected are for target sequences located in proximity to the 5′- and 3′-ends of and within the gene. Any assay(s) detected to have gain or loss of copy number(s) may indicate, at least partially, the copy number of the SPARC gene.

Data analysis

Segregation analysis was conducted for variants detected in the pedigree, including copy number variation. A variant is considered disease-causing if it segregates with disease in the pedigree. For the two novel intronic variants detected in the Chinese subjects, a web-based program Automated Splice Site Analyses (ASSA) [45,46] was used to predict their impacts to alternative splicing. For variants with a minor allele frequency of >1%, Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium was tested by the χ2 test. Variant frequencies between patients and controls were compared by Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test using SPSS (ver. 16.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Linkage disequilibrium (LD) between SNPs and haplotype frequencies were estimated using the E-M algorithm in Haploview [47] and tested for association using χ2 analysis. A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Since no significant association was detected, correction for multiple testing was not considered.

Results

Sequence variants detected in SPARC

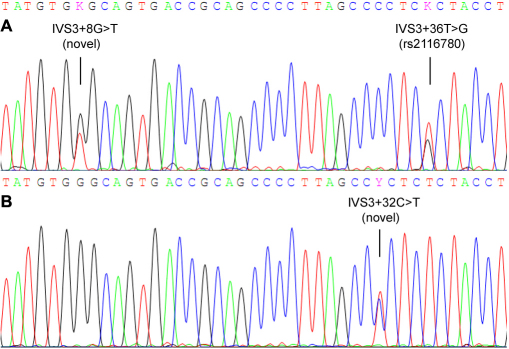

In the Philippine pedigree, only one SPARC variant, namely c.912+29 C>G (rs1053411), was detected in an unaffected subject. No sequence change was found in other family members. In the Chinese study subjects, 11 variants were detected (Table 4), among which two were novel, i.e., IVS2+8G>T and IVS2+32C>T (Figure 1). The heterozygous variant IVS2+8G>T was detected in two (2.1%) control subjects but not in patients, while the IVS2+32C>T was detected in one (2.2%) patient and absent in controls. According to the ASSA program, the two novel variants were predicted to cause no change in the information content of the donor site, suggesting that they are not likely to be functional mutations. The other 9 variants were known polymorphisms in the dbSNP database. Except for a synonymous SNP rs2304052 (p.Glu22Glu) detected in exon 2, all other SNPs were located in noncoding regions. All of these SNPs followed HWE in both the control and patient groups. Moreover, the allele or genotype distribution of each SNP was not significantly different between patients and controls, indicating no association with glaucoma. Linkage disequilibrium analysis revealed an extension of LD throughout the gene. The five most common SNPs, rs2116780 (Intron 3), rs1978707 (Intron 4), rs7719521 (Intron 5), rs729853 (Intron 7), and rs1053411 (3′-untranslated region, 3′-UTR), were contained in a LD block spanning approximately 11 kb (Figure 2A). Haplotype-based association analysis showed that no haplotype was significantly associated with the disorder (Figure 2B).

Table 4. SPARC variants detected in Chinese JPOAG and control subjects.

| |

|

|

|

Minor allele frequency (%) |

Genotype counts |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Sequence change | Residue change | SNP ID | Case (n=92) | Control (n=190) | p | Case (n=46) | Control (n=95) | p |

| Exon 1 |

c.-186G>A* |

– |

rs4958281 |

5 (5.4) |

6 (3.2) |

0.35 |

0/5/41 |

0/6/89 |

0.34 |

| Intron 2 |

IVS2+56G>C |

– |

rs7714314 |

3 (3.3) |

7 (3.7) |

1.0 |

0/3/43 |

1/5/89 |

0.75 |

| Exon 3 |

c.66A>G |

Glu22Glu |

rs2304052 |

2 (2.2) |

5 (2.6) |

1.0 |

0/2/44 |

0/5/90 |

1.0 |

| Intron 3 |

IVS3+8G>T |

– |

novel |

0 (0) |

2 (1.1) |

- |

0/0/46 |

0/2/93 |

- |

| Intron 3 |

IVS3+32C>T |

– |

novel |

1 (1.1) |

0 (0) |

- |

0/1/45 |

0/0/95 |

- |

| Intron 3 |

IVS3+36T>G |

– |

rs2116780 |

36 (39.1) |

77 (40.5) |

0.82 |

7/22/17 |

15/47/33 |

0.97 |

| Intron 3 |

IVS3+42T>C |

– |

rs2304051 |

4 (4.3) |

6 (3.2) |

0.73 |

0/4/42 |

0/6/89 |

0.73 |

| Intron 4 |

IVS4+31C>T |

– |

rs1978707 |

45 (48.9) |

92 (48.4) |

0.94 |

10/25/11 |

24/44/27 |

0.67 |

| Intron 5 |

IVS5–59T>G |

– |

rs7719521 |

44 (47.8) |

89 (46.8) |

0.88 |

10/24/12 |

22/45/28 |

0.86 |

| Intron 7 |

IVS7+100G>A |

– |

rs729853 |

38 (41.3) |

80 (42.1) |

0.90 |

7/24/15 |

16/48/31 |

0.97 |

| 3′-UTR | c.912+29C>G | – | rs1053411 | 39 (42.4) | 80 (42.1) | 0.96 | 8/23/15 | 16/48/31 | 0.99 |

*This SNP is located 186 bp upstream the start codon “ATG”; 3′-UTR: 3′-untranslated region.

Figure 1.

Chromatograms of the novel SPARC variants detected in this study. A: The variant IVS3+8G>T detected in a control subject, this participant is also heterozygous for the rs2116780:T>G polymorphism. B: The variant IVS3+32C>T detected in a Chinese patient with JPOAG.

Figure 2.

Linkage disequilibrium and haplotype association analyses for the SPARC variants detected in this study. A: Linkage disequilibrium plot of 11 SNPs of the SPARC gene in the combined subjects. D' values corresponding to each SNP pair are expressed as a percentage and shown within the respective square. The five most common SNPs constitute a haplotype block spanning from intron 3 to the 3′-UTR of the gene. B: Haplotype-based association analysis of the 5 most common SNPs in the LD block with JPOAG. The frequencies of each haplotype in the patient and control groups were presented in percentage. Only those haplotypes with frequencies >1% were shown.

Copy number analysis of SPARC

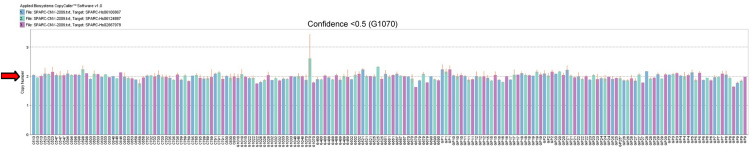

The three assays were unequivocally genotyped in all subjects (n=63), with call rates of 100%, to obtain predicted copy numbers of the target sequences in SPARC in each subject (Figure 3). The confidence of prediction was greater than 95% for each assay in each subject, except for the sample G1070, with a confidence <50% for assay Hs06124887_cn. This sample was predicted to have 3 copies of the target sequence by this assay but was predicted to have 2 copies of the target sequences by the other two assays with confidence >99%. Therefore, this subject is more likely to have 2 gene copies. All the other samples were predicted to have 2 copies of the gene by any assay, suggesting no correlation between the copy number of SPARC and JPOAG.

Figure 3.

Copy number of the SPARC gene in the family members from the Philippine pedigree and the randomly selected Chinese JPOAG patients and controls. Each bar represents the copy number prediction of the target sequence in each subject. And each color presents each copy number assay. Thus, each individual is represented by three bars. The red arrow indicates the reference line for two copies. One sample (G1070) was predicted to have a copy number of 3 but with a confidence of <50%.

Discussion

JPOAG is a subset of POAG characterized by an early age of onset and severe elevations of intraocular pressure. It is often inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern [20], but sporadic cases exist. Thick, compact tissue and extracellular deposits have been found in trabecular meshwork specimens obtained from JPOAG patients during trabeculectomy [48]. It is thus likely that the abnormal trabecular meshwork and aqueous outflow could result in an elevation of IOP and subsequently the glaucomatous changes. The identification of the myocilin gene accounting mainly for JPOAG [25] and its mutant products leading to elevated IOP [2] also supports the possibility that other genes affecting the structure of trabecular meshwork and outflow resistance may function to regulate IOP and, once mutated, increase the risk of glaucoma. However, identification of such genes has since been unfruitful. The tendency for familial inheritance in JPOAG has facilitated the mapping of linkage loci for this phenotype, and at least five loci have been identified, including GLC1A (1q21–31, MYOC) [8,25], GLC1J (9q22) [16], GLC1K (20p12) [16], GLC1M (5q22.1–32) [20], and GLC1N (15q22–24) [21]. Thus, except for GLC1A, investigating genes on the other loci may lead to the discovery of new disease genes for JPOAG.

We have previously mapped the GLC1M locus in a Philippine pedigree with JPOAG, in which affected family members had moderate IOP elevation (mean±SD: 32±6.3 mmHg) [20]. Therefore, it is likely that this locus harbors a gene involved in IOP regulation. We selected SPARC as a candidate causative gene for glaucoma mainly based on that the SPARC protein may function to promote extracellular matrix deposition [31] and is rich in eye tissues, especially in the trabecular meshwork and the juxtacanalicular region [35], that SPARC in TM cells is regulated by elevated IOP and mechanical stretching [38,39], that SPARC null mice have lower IOP [41], and that SPARC has been mapped to 5q31.3-q32 within the GLC1M (5q22.1–32) locus. However, we did not find any putative mutation or copy number variants in the affected and unaffected subjects from the GLC1M-linked Philippine pedigree. Although some members, e.g., the 3-year-old unaffected subject, may develop glaucoma later in life, it is likely to be independent of SPARC. As such, SPARC could be excluded as the gene responsible for the linkage signal. Discrepancy is known to exist between genetic and physical maps. According to the Ensembl database [44], SPARC (ENSG00000113140) is physically located in the region of 151,040,657–151,066,726 bp at chromosome 5. This region is outside the critical interval defined by the makers D5S2051 (111,009,257–111,009,520) and D5S2090 (147,230,043–147,230,236) [20]. Therefore, although SPARC by itself is a good candidate gene for glaucoma, it may not be responsible for JPOAG in the pedigree. As such, the causal gene for glaucoma at the GLC1M locus remains to be identified. Recently, with the advent of the next-generation sequencing platform [49], the sequencing capacity has been greatly enhanced. It has been used successfully in pinpointing the genes for some Mendelian disorders [50,51]. Such technologies should speed up the identification of glaucoma genes.

We did not detect any missense changes in SPARC in a group of unrelated JPOAG patients and controls. Moreover, of the 11 variants detected, none was associated with glaucoma, either individually or involved in a haplotype. Our sample of 46 patients might be small to provide adequate statistical power to detect the significance. However, the distributions of the genotypes were drastically similar between the patients and controls. It is unlikely that the lack of association was due to insufficient power. Therefore, we expect that SPARC gene variants do not have a major contribution to JPOAG genetics. However, it is still possible that rare variants in this gene may contribute to a small portion of patients, which awaits confirmation by screening the gene in a very large sample. It is also possible that variants located outside the coding region of the gene, e.g., those at the 3′-UTR, may contribute to the disease. It has been reported that a SNP at the 3′-UTR of SPARC, i.e., +998C>G (equivalent to SNP rs1053411 in the present study), was associated with systemic sclerosis in different populations, and the C/C genotype was correlated with a longer mRNA half-life in normal fibroblasts, than were heterozygotes (G/C). And it was suggested that this may contribute, at least in part, to increased SPARC gene expression [52]. However, such association could not be reproduced in another cohort of Caucasian patients [53]. In our study, no significant association was detected for rs1053411, which is in strong LD with the other common SNPs detected. According to the international HapMap project, the SNPs that located at the 3′-UTR of SPARC are also in strong LD (data not shown). Therefore, other common SNPs at the 3′-UTR are not likely to be associated with JPOAG, because the haplotypes detected in this study did not have disease association (Figure 2B). As such, if the correlation between C/C genotype at rs1053411 and an increased-SPARC expression is real, as that suggested by Zhou et al. [52], it is likely that such an extent of increased-SPARC expression is not causative for glaucoma. However, whether a more severely elevated expression of the protein, if triggered by other pathological factors, can cause glaucoma remains to be further investigated.

So far, the involvement of the SPARC protein level in the pathogenesis of glaucoma is unknown. SPARC occurs widely in extracellular matrices and is predominantly expressed during embryogenesis and in adult tissues undergoing remodeling or repair. It is believed to play a modulatory role in cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, differentiation, ECM production and organization, wound healing, and angiogenesis [54-56], suggesting a fundamental role of SPARC to living cells [56]. SPARC has been implicated in multiple systemic as well as ocular conditions. For example, it is expressed at high levels in bone tissues and acts as a major non-collagenous protein of the bone matrix [32,57]. SPARC null mice have low-turnover osteopenia [58], and it was suggested that SPARC may strengthen bone [59]. Moreover, SPARC 3′-UTR polymorphisms had been associated with bone density in Caucasian men with idiopathic osteoporosis [60]. Likewise, SPARC null mice have lower IOP [41]. It could thus be hypothesized that increased-SPARC level may elevate IOP and predispose to glaucoma. In the eye, increased SPARC level has been correlated with cataract [61], corneal wound repair [62], and proliferative diabetic retinopathy [63]. In glaucoma, elevated SPARC expression has been detected in the iris of POAG and primary angle closure glaucoma patients [40]. All these findings, in addition to the genetic findings of this present study, suggest that certain SPARC expression level could play a role in eye diseases. However, the correlation between the expression of SPARC and the occurrence of these eye diseases remained to be clarified. Recently, it has been found that SPARC deficiency in mice resulted in improved surgical survival in a mouse model of glaucoma filtration surgery [64]. Whether the SPARC levels in glaucoma patients is correlated with the success rate of filtration surgery is unknown. If such correlation exists, a pre-operative detection of the SPARC level may help with a better treatment plan.

This study is one of several attempts to evaluate the involvement of copy number variation in POAG. Abu-Amero et al. [65] screened 27 Caucasian and African-American POAG patients and 12 ethnically matched controls for chromosomal copy number alterations using high resolution array comparative genomic hybridization. No chromosomal deletions or duplications were detected in POAG patients compared to controls [65]. Davis et al. [66] performed a whole-genome copy number screening in a cohort of 400 patients with POAG and 100 controls and found that rare copy number variations in the DMXL1, TULP3, and PAK7 genes may affect development of POAG. Interestingly, the DMXL1 gene at 5q23.1 is located within the GLC1M locus. This suggests that copy number of certain genes at this locus, including DMXL1, may contribute to the genetics of POAG. However, our findings in that all of the 27 subjects from the Philippine family and the 36 Chinese subjects were detected to carry two copies of the SPARC gene, indicate that copy number variation of SPARC is at least not a common phenomenon in the two populations and thus unlikely to be a major genetic contributor to JPOAG. Whether copy number variations in other genes at the GLC1M locus, such as DMXL1, contribute to glaucoma remain to be investigated.

In summary, by mutation screening and copy number analysis, we have excluded SPARC as the causal gene at the GLC1M locus in the Philippine pedigree with JPOAG. Our results also suggest that SPARC is unlikely to be a major disease causative or associated gene of JPOAG. Further investigations are warranted to unravel the involvement of SPARC in the pathogenesis of glaucoma, and also to identify the causal gene at GLC1M for JPOAG.

Acknowledgments

We express our greatest gratitude to all the participants in this study. The work in this paper was supported in part by the Endowment Fund for Lim Por-Yen Eye Genetics Research Centre, Hong Kong, and research grant 2140597 from the General Research Fund, Hong Kong.

References

- 1.Weinreb RN, Khaw PT. Primary open-angle glaucoma. Lancet. 2004;363:1711–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwon YH, Fingert JH, Kuehn MH, Alward WL. Primary open-angle glaucoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1113–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Etya'ale D, Kocur I, Pararajasegaram R, Pokharel GP, Mariotti SP. Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:844–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:262–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.081224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foster PJ, Oen FT, Machin D, Ng TP, Devereux JG, Johnson GJ, Khaw PT, Seah SK. The prevalence of glaucoma in Chinese residents of Singapore: a cross-sectional population survey of the Tanjong Pagar district. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:1105–11. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.8.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He M, Foster PJ, Ge J, Huang W, Zheng Y, Friedman DS, Lee PS, Khaw PT. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of glaucoma in adult Chinese: a population-based study in Liwan District, Guangzhou. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2782–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Libby RT, Gould DB, Anderson MG, John SW. Complex genetics of glaucoma susceptibility. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2005;6:15–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.6.080604.162209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheffield VC, Stone EM, Alward WL, Drack AV, Johnson AT, Streb LM, Nichols BE. Genetic linkage of familial open angle glaucoma to chromosome 1q21-q31. Nat Genet. 1993;4:47–50. doi: 10.1038/ng0593-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stoilova D, Child A, Trifan OC, Crick RP, Coakes RL, Sarfarazi M. Localization of a locus (GLC1B) for adult-onset primary open angle glaucoma to the 2cen-q13 region. Genomics. 1996;36:142–50. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wirtz MK, Samples JR, Kramer PL, Rust K, Topinka JR, Yount J, Koler RD, Acott TS. Mapping a gene for adult-onset primary open-angle glaucoma to chromosome 3q. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:296–304. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trifan OC, Traboulsi EI, Stoilova D, Alozie I, Nguyen R, Raja S, Sarfarazi M. A third locus (GLC1D) for adult-onset primary open-angle glaucoma maps to the 8q23 region. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126:17–28. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarfarazi M, Child A, Stoilova D, Brice G, Desai T, Trifan OC, Poinoosawmy D, Crick RP. Localization of the fourth locus (GLC1E) for adult-onset primary open-angle glaucoma to the 10p15-p14 region. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:641–52. doi: 10.1086/301767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wirtz MK, Samples JR, Rust K, Lie J, Nordling L, Schilling K, Acott TS, Kramer PL. GLC1F, a new primary open-angle glaucoma locus, maps to 7q35-q36. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:237–41. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiggs JL, Allingham RR, Hossain A, Kern J, Auguste J, DelBono EA, Broomer B, Graham FL, Hauser M, Pericak-Vance M, Haines JL. Genome-wide scan for adult onset primary open angle glaucoma. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1109–17. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.7.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nemesure B, Jiao X, He Q, Leske MC, Wu SY, Hennis A, Mendell N, Redman J, Garchon HJ, Agarwala R, Schaffer AA, Hejtmancik F. A genome-wide scan for primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG): the Barbados Family Study of Open-Angle Glaucoma. Hum Genet. 2003;112:600–9. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-0910-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiggs JL, Lynch S, Ynagi G, Maselli M, Auguste J, Del Bono EA, Olson LM, Haines JL. A genomewide scan identifies novel early-onset primary open-angle glaucoma loci on 9q22 and 20p12. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:1314–20. doi: 10.1086/421533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baird PN, Foote SJ, Mackey DA, Craig J, Speed TP, Bureau A. Evidence for a novel glaucoma locus at chromosome 3p21–22. Hum Genet. 2005;117:249–57. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-1296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monemi S, Spaeth G, DaSilva A, Popinchalk S, Ilitchev E, Liebmann J, Ritch R, Heon E, Crick RP, Child A, Sarfarazi M. Identification of a novel adult-onset primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) gene on 5q22.1. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:725–33. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allingham RR, Wiggs JL, Hauser ER, Larocque-Abramson KR, Santiago-Turla C, Broomer B, Del Bono EA, Graham FL, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA, Hauser MA. Early adult-onset POAG linked to 15q11–13 using ordered subset analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2002–5. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pang CP, Fan BJ, Canlas O, Wang DY, Dubois S, Tam PO, Lam DS, Raymond V, Ritch R. A genome-wide scan maps a novel juvenile-onset primary open angle glaucoma locus to chromosome 5q. Mol Vis. 2006;12:85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang DY, Fan BJ, Chua JK, Tam PO, Leung CK, Lam DS, Pang CP. A genome-wide scan maps a novel juvenile-onset primary open-angle glaucoma locus to 15q. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:5315–21. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suriyapperuma SP, Child A, Desai T, Brice G, Kerr A, Crick RP, Sarfarazi M. A new locus (GLC1H) for adult-onset primary open-angle glaucoma maps to the 2p15-p16 region. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:86–92. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin Y, Liu T, Li J, Yang J, Du Q, Wang J, Yang Y, Liu X, Fan Y, Lu F, Chen Y, Pu Y, Zhang K, He X, Yang Z. A genome-wide scan maps a novel autosomal dominant juvenile-onset open-angle glaucoma locus to 2p15–16. Mol Vis. 2008;14:739–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiao X, Yang Z, Yang X, Chen Y, Tong Z, Zhao C, Zeng J, Chen H, Gibbs D, Sun X, Li B, Wakins WS, Meyer C, Wang X, Kasuga D, Bedell M, Pearson E, Weinreb RN, Leske MC, Hennis A, DeWan A, Nemesure B, Jorde LB, Hoh J, Hejtmancik JF, Zhang K. Common variants on chromosome 2 and risk of primary open-angle glaucoma in the Afro-Caribbean population of Barbados. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:17105–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907564106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stone EM, Fingert JH, Alward WL, Nguyen TD, Polansky JR, Sunden SL, Nishimura D, Clark AF, Nystuen A, Nichols BE, Mackey DA, Ritch R, Kalenak JW, Craven ER, Sheffield VC. Identification of a gene that causes primary open angle glaucoma. Science. 1997;275:668–70. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rezaie T, Child A, Hitchings R, Brice G, Miller L, Coca-Prados M, Heon E, Krupin T, Ritch R, Kreutzer D, Crick RP, Sarfarazi M. Adult-onset primary open-angle glaucoma caused by mutations in optineurin. Science. 2002;295:1077–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1066901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leung YF, Fan BJ, Lam DS, Lee WS, Tam PO, Chua JK, Tham CC, Lai JS, Fan DS, Pang CP. Different optineurin mutation pattern in primary open-angle glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3880–4. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fan BJ, Wang DY, Lam DS, Pang CP. Gene mapping for primary open angle glaucoma. Clin Biochem. 2006;39:249–58. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fan BJ, Wang DY, Fan DS, Tam PO, Lam DS, Tham CC, Lam CY, Lau TC, Pang CP. SNPs and interaction analyses of myocilin, optineurin, and apolipoprotein E in primary open angle glaucoma patients. Mol Vis. 2005;11:625–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fan BJ, Wang DY, Cheng CY, Ko WC, Lam SC, Pang CP. Different WDR36 mutation pattern in Chinese patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. Mol Vis. 2009;15:646–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rhee DJ, Haddadin RI, Kang MH, Oh DJ. Matricellular proteins in the trabecular meshwork. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:694–703. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maillard C, Malaval L, Delmas PD. Immunological screening of SPARC/Osteonectin in nonmineralized tissues. Bone. 1992;13:257–64. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(92)90206-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan Q, Clark JI, Sage EH. Expression and characterization of SPARC in human lens and in the aqueous and vitreous humors. Exp Eye Res. 2000;71:81–90. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wirtz MK, Bradley JM, Xu H, Domreis J, Nobis CA, Truesdale AT, Samples JR, Van Buskirk EM, Acott TS. Proteoglycan expression by human trabecular meshworks. Curr Eye Res. 1997;16:412–21. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.16.5.412.7040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rhee DJ, Fariss RN, Brekken R, Sage EH, Russell P. The matricellular protein SPARC is expressed in human trabecular meshwork. Exp Eye Res. 2003;77:601–7. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(03)00190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Magee RM, Hagan S, Hiscott PS, Sheridan CM, Carron JA, McGalliard J, Grierson I. Synthesis of osteonectin by human retinal pigment epithelial cells is modulated by cell density. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:2707–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez IR, Moreira EF, Bok D, Kantorow M. Osteonectin/SPARC secreted by RPE and localized to the outer plexiform layer of the monkey retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:2438–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Comes N, Borras T. Individual molecular response to elevated intraocular pressure in perfused postmortem human eyes. Physiol Genomics. 2009;38:205–25. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.90261.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vittal V, Rose A, Gregory KE, Kelley MJ, Acott TS. Changes in gene expression by trabecular meshwork cells in response to mechanical stretching. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2857–68. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chua J, Seet LF, Jiang Y, Su R, Htoon HM, Charlton A, Aung T, Wong TT. Increased SPARC expression in primary angle closure glaucoma iris. Mol Vis. 2008;14:1886–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haddadin RI, Oh DJ, Kang MH, Filippopoulos T, Gupta M, Hart L, Sage EH, Rhee DJ. SPARC-null mice exhibit lower intraocular pressures. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:3771–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang DY, Fan BJ, Canlas O, Tam PO, Ritch R, Lam DS, Fan DS, Pang CP. Absence of myocilin and optineurin mutations in a large Philippine family with juvenile onset primary open angle glaucoma. Mol Vis. 2004;10:851–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rozen S, Skaletsky H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;132:365–86. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hubbard T, Barker D, Birney E, Cameron G, Chen Y, Clark L, Cox T, Cuff J, Curwen V, Down T, Durbin R, Eyras E, Gilbert J, Hammond M, Huminiecki L, Kasprzyk A, Lehvaslaiho H, Lijnzaad P, Melsopp C, Mongin E, Pettett R, Pocock M, Potter S, Rust A, Schmidt E, Searle S, Slater G, Smith J, Spooner W, Stabenau A, Stalker J, Stupka E, Ureta-Vidal A, Vastrik I, Clamp M. The Ensembl genome database project. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:38–41. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rogan PK, Faux BM, Schneider TD. Information analysis of human splice site mutations. Hum Mutat. 1998;12:153–71. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1998)12:3<153::AID-HUMU3>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nalla VK, Rogan PK. Automated splicing mutation analysis by information theory. Hum Mutat. 2005;25:334–42. doi: 10.1002/humu.20151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Furuyoshi N, Furuyoshi M, Futa R, Gottanka J, Lutjen-Drecoll E. Ultrastructural changes in the trabecular meshwork of juvenile glaucoma. Ophthalmologica. 1997;211:140–6. doi: 10.1159/000310781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mardis ER. Next-generation DNA sequencing methods. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2008;9:387–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ng SB, Turner EH, Robertson PD, Flygare SD, Bigham AW, Lee C, Shaffer T, Wong M, Bhattacharjee A, Eichler EE, Bamshad M, Nickerson DA, Shendure J. Targeted capture and massively parallel sequencing of 12 human exomes. Nature. 2009;461:272–6. doi: 10.1038/nature08250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ng SB, Buckingham KJ, Lee C, Bigham AW, Tabor HK, Dent KM, Huff CD, Shannon PT, Jabs EW, Nickerson DA, Shendure J, Bamshad MJ. Exome sequencing identifies the cause of a mendelian disorder. Nat Genet. 2010;42:30–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou X, Tan FK, Reveille JD, Wallis D, Milewicz DM, Ahn C, Wang A, Arnett FC. Association of novel polymorphisms with the expression of SPARC in normal fibroblasts and with susceptibility to scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2990–9. doi: 10.1002/art.10601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lagan AL, Pantelidis P, Renzoni EA, Fonseca C, Beirne P, Taegtmeyer AB, Denton CP, Black CM, Wells AU, du Bois RM, Welsh KI. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the SPARC gene are not associated with susceptibility to scleroderma. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:197–201. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lane TF, Sage EH. The biology of SPARC, a protein that modulates cell-matrix interactions. FASEB J. 1994;8:163–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sage EH, Bornstein P. Extracellular proteins that modulate cell-matrix interactions. SPARC, tenascin, and thrombospondin. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:14831–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bradshaw AD, Sage EH. SPARC, a matricellular protein that functions in cellular differentiation and tissue response to injury. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1049–54. doi: 10.1172/JCI12939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Termine JD, Kleinman HK, Whitson SW, Conn KM, McGarvey ML, Martin GR. Osteonectin, a bone-specific protein linking mineral to collagen. Cell. 1981;26:99–105. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mansergh FC, Wells T, Elford C, Evans SL, Perry MJ, Evans MJ, Evans BA. Osteopenia in Sparc (osteonectin)-deficient mice: characterization of phenotypic determinants of femoral strength and changes in gene expression. Physiol Genomics. 2007;32:64–73. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00151.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kos K, Wilding JP. SPARC: a key player in the pathologies associated with obesity and diabetes. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2010;6:225–35. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2010.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Delany AM, McMahon DJ, Powell JS, Greenberg DA, Kurland ES. Osteonectin/SPARC polymorphisms in Caucasian men with idiopathic osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:969–78. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0523-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kantorow M, Huang Q, Yang XJ, Sage EH, Magabo KS, Miller KM, Horwitz J. Increased expression of osteonectin/SPARC mRNA and protein in age-related human cataracts and spatial expression in the normal human lens. Mol Vis. 2000;6:24–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Berryhill BL, Kane B, Stramer BM, Fini ME, Hassell JR. Increased SPARC accumulation during corneal repair. Exp Eye Res. 2003;77:85–92. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(03)00060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Watanabe K, Okamoto F, Yokoo T, Iida KT, Suzuki H, Shimano H, Oshika T, Yamada N, Toyoshima H. SPARC is a major secretory gene expressed and involved in the development of proliferative diabetic retinopathy. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2009;16:69–76. doi: 10.5551/jat.e711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seet LF, Su R, Barathi VA, Lee WS, Poh R, Heng YM, Manser E, Vithana EN, Aung T, Weaver M, Sage EH, Wong TT. SPARC deficiency results in improved surgical survival in a novel mouse model of glaucoma filtration surgery. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abu-Amero KK, Hellani A, Bender P, Spaeth GL, Myers J, Katz LJ, Moster M, Bosley TM. High-resolution analysis of DNA copy number alterations in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. Mol Vis. 2009;15:1594–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Davis L, Meyer K, Schindler E, Beck J, Rudd D, Grundstad A, Scheetz T, Braun T, Fingert J, Folk J, Russell S, Wassink T, Sheffield V, Stone E. A large scale study of copy number variation implicates the genes DMXL1 and TULP3 in the etiology of primary open angle glaucoma. Presented at the 59th Annual Meeting of The American Society of Human Genetics, October 24, 2009, Honolulu, Hawaii. [Google Scholar]