Abstract

This report investigates the influence of liver transplantation and concomitant immunosuppression on the course of progression of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and discusses statistical methodology appropriate for such settings. The data on 303 patients who underwent liver transplantation for primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) were analyzed using person-time analysis and Cox regression, with the duration of IBD as the time variable and transplantation as a segmented time-dependent covariate, to take into account both posttransplant and pretransplant history of IBD. The need for colectomy and appearance of colorectal cancer were taken as outcome measures. The only significant risk factor in the multivariate model for colectomy was transplantation itself, which increased the risk of colectomy due to intractable disease (Wald statistic; P = .001). None of the variables available for analysis were found to influence the risk of colon cancer significantly. Graphs showing the dependence of the instantaneous risk of cancer on the time from onset of IBD and its independence from the latter in the case of colectomy are presented. The use of a unique statistical methodology described for the first time in this setting led us to the somewhat surprising conclusion that transplantation and concomitant use of immunosuppression accelerate the progression of IBD. At the same time, transplantation does not affect the incidence of colorectal cancer. These results confirm the findings of some recent studies and can potentially shed new light on the disease pathogenesis.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a chronic, progressive, cholestatic liver disease characterized by inflammation and fibrosis of the biliary tree that eventually causes biliary cirrhosis. Despite an association between PSC and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in 55% to 75% of cases,1 neither a common pathogenesis nor a direct cause-effect relationship for the 2 disorders has been unequivocally identified. Orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) is the only definitive treatment for patients with advanced PSc.2 The immunosuppressive therapy needed to control rejection after transplantation is also potentially effective in controlling IBD3–8 except in those with refractory disease.9

Thus, a number of retrospective studies have attempted to determine whether hepatic replacement and the concomitant use of different immunosuppressive regimens influences the natural history of IBD in this unique population. 10–20 This study is unique for 2 reasons: (1) special emphasis was placed on the course of the disease before the need for hepatic replacement and (2) the applied statistical methodology enabled assessment of the simultaneous effect of multiple time-dependent factors on the outcome of interest.

Materials and Methods

Between 1981 and 1997,303 patients underwent OLT for PSC at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. A total of 206 of these patients developed IBD before OLT. The date of diagnosis of IBD was confirmed in all study patients by histopathologic examination of tissue samples. The date of diagnosis of PSC before transplantation was recorded. The diagnosis of PSC was confirmed in all patients by histologic examination of the hepatectomy specimen removed at the time of OLT. Fourteen of the 206 patients with IBD underwent large bowel resection before the diagnosis of PSC was established. Patient demographics and transplantation information, including immunosuppression and survival, were retrieved from our computerized database. All other pertinent data, including the date and indication for colectomy, were obtained from a chart review. Follow-up data were obtained during outpatient visits and from telephone interviews with the patient and/or primary care physicians. The study was approved by the institutional review board.

Study Population

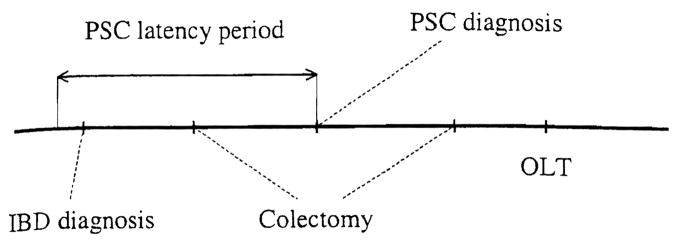

Inclusion criteria for the study were coexistence of IBD and PSC at any time before liver transplantation and well-documented dates of diagnoses. This information was required to effectively study the relationship between these diseases and liver replacement. Therefore, 14 patients who underwent colectomy before the diagnosis of PSC were excluded from the 206, leaving a total of 192 study cases. The only limitation imposed by this selection criterion, which is applicable to similar studies, was the undetermined delay between the actual onset of disease and the date of diagnosis (Fig. 1). Regardless of this, the validity of the resulting statistical model was unequivocally verified by repeating the analysis on a set including these 14 patients.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of key events in the modeled setting. Two possibilities for positioning of colectomy relative to a potential PSC latency period are shown.

The baseline immunosuppressive regimen included cyclosporine (Novartis, East Hanover, NJ) in 96 patients (50%) and tacrolimus (Fujisawa, Deerfield, IL) in the remaining 96 patients; corticosteroids were used with both drugs from the outset for all patients, Azathioprine (Imuran; Glaxo Wellcome, Research Triangle Park, NC) or more recently mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept; Roche Laboratories, Nutley, NJ) was used as a third drug in selected cases. Thirty-seven of the 96 patients (38.5%) receiving cyclosporine were converted to tacrolimus at various times after transplantation because of acute or chronic liver allograft rejection. By the last date of follow-up, the patients who were administered tacrolimus received it for an average of 4.72 years (SD, 2.71 years); patients who were administered cyclosporine received it for an average of 5.29 years (SD, 4.77 years). Acute rejection episodes were treated with high doses of corticosteroids; OKT3 monoclonal antibody (Ortho, Raritan, NJ) was used in a few cases to treat severe and corticosteroid-resistant rejection. Dose adjustments of cyclosporine or tacrolimus were guided primarily by rejection, drug toxicity, and time after transplantation. The maintenance immunosuppressive regimen, particularly withdrawal of corticosteroids, was not influenced at any time during the follow-up period by the diagnosis of IBD.

A total of 180 of the 192 study patients (94%) were white, and 134 (70%) were men. IBD was predominantly ulcerative colitis (86%); the remaining 27 patients had either Crohn’s disease or indeterminate pathology. PSC was diagnosed after IBD in 124 cases. In the remaining cases, PSC was diagnosed at the same time (n = 21) or before (n = 47) diagnosis of IBD. Mean age at the time of diagnosis of IBD was 31.7 years. Retransplantation was required for 36 primary recipients (23.5%).

Patients not treated with complete colorectal resection were subjected to a full colonoscopic examination when initially evaluated for OLT. Surveillance colonoscopy was performed at least every 1 to 2 years both before and after transplantation and more often in those with symptomatic disease. Indications for colorectal resection were recalcitrant or complicated disease including bleeding, toxic megacolon, colonic dysplasia, and colorectal cancer. Neither the presence of IBD nor prior colectomy influenced the surgical techniques used during OLT.

Outcome Measures

Progression of IBD before or after transplantation was determined by the need for colectomy, whether due to clinically intractable disease, bleeding, dysplasia, or colorectal cancer. Because of the retrospective nature and long duration of the study, histopathologic documentation of colonic dysplasia was at best incomplete and was not included in the analysis. Because the aim of the study was to evaluate the effect of OLT on the natural progression of IBD, time 0 in both models was the date of diagnosis of IBD.

Statistical Methods

Patients with active IBD are commonly treated with corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive agents to control active disease, but these agents are also well-known risk factors for the development of cancer, particularly among the transplantation population. Because of these 2 potential opposing influences and the current controversy concerning the risk of colorectal cancer, statistical models used in this report were designed around the indication for colectomy. Two separate models were developed: one for colectomy performed because of intractable disease, defined as refractory IBD or bleeding, and another for colorectal cancer. In the former model, patients undergoing colectomy for other indications (cancer, posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease, or perforation) were censored. In the cancer model, patients who underwent colectomy for nonmalignant indications were censored because they were no longer at risk for the disease. Time 0 in both models was the date of diagnosis of IBD.

The predictive significance and the proportionality of hazards assumption for potential risk factors were investigated by univariate Cox regression analysis containing the factor under consideration and the same factor combined in a product with time:

| (1) |

where t is the time from the onset of IBD, h(t) is the hazard function, and X is the risk factor. Nonconvergent coefficients for variables in univariate Cox regression were tested for significance by person-time analysis, with CIs for incidence rate ratio calculated using the approximate Poisson method.21 P values less than .05 were considered significant in multivariate analysis and in testing the proportional hazards assumption.

Potential risk factors considered in univariate analysis included the following: age at the time of diagnosis of IBD, race, type of IBD, chronological order of dates of diagnosis of IBD and PSC, baseline immunosuppressive regimen, duration of IBD before diagnosis of PSC, and time of transplantation. The univariate model of the immunosuppressive regimen included the type of immunosuppression and its product with transplantation, defined as a segmented time-dependent covariate:

| (2) |

Multivariate models had the following form:

| (3) |

where δi = 0 if the proportionality of hazards assumption holds based on the Wald statistic for the regression coefficient in univariate analysis and 1 otherwise, Xi are the risk factors selected as described above, and Bi, Bi′ are the corresponding regression coefficients.

Results

Mean duration of patient follow-up after OLT was 5.91 years (SD, 4.12 years). Post-OLT patient survival rates estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method at 1,5, and 10 years were 90.1%, 72.7%, and 62.2%, respectively. Fifty-six of the 192 patients were treated with colectomy. The indications were refractory disease (n = 39), colorectal cancer (n = 13), posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease (n = 1), and colonic perforation (n = 3). Twenty-three of the colectomies were performed before OLT for refractory disease (n = 17) or colorectal cancer (n = 6). The remaining 33 colectomies were performed after OLT because of refractory disease (n = 22), colorectal cancer (n = 7), posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease (n = 1), or colonic perforation (n = 3).

For the model of colectomy due to intractable disease, only 2 potential risk factors, age older than 30 years at the time of diagnosis of IBD and OLT, proved to be significant in univariate analysis. The multivariate Cox model is shown in Table 1. Exclusion of patients with retransplants did not affect the significance of risk factors in the analysis. Therefore, patients were retained in the data set regardless of the number of transplants. As shown in Table 1, OLT was the only significant risk factor for colectomy due to intractable disease.

Table 1.

Multivariate Model of Colectomy due to Intractable Disease

| Variable | B | Hazard Ratio = Exp(B) | P Value for Wald Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at the time of diagnosis of IBD (1 if older than 30 years, 0 otherwise) | 0.409 | 1.505 | .228 |

| OLT (segmented time-dependent covariate) | 1.141 | 3.129 | .001 |

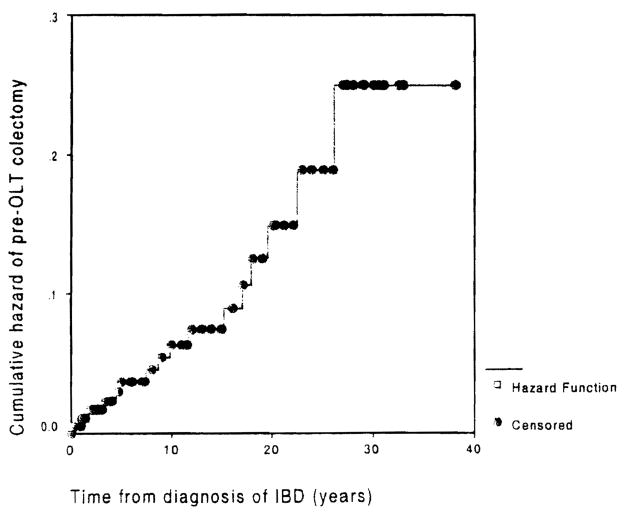

Because the latter finding was rather unexpected, the result was further substantiated using person-time analysis as follows. Cumulative hazard of colectomy before OLT plotted against duration of IBD is close to a straight line (Fig. 2), which indicates that the distribution of instantaneous colectomy hazard is uniform relative to duration of IBD. With the assumption that OLT does not change this relationship, the incidence rates were calculated for colectomy before OLT by truncation of person-time at the time of OLT. For colectomy after OLT, accrual of person-time began on the date of OL T. The incidence rates for colectomy were 0.007 before OLT and 0.025 after OLT. The incidence rate ratio was 0.29 (95% CI, 0.15–0.54). The influence of OLT on colectomy, illustrated by yearly incidence rates relative to time of transplantation, is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

Cumulative pre-OLT hazard of colectomy due to intractable disease. The curve can be approximated by a straight line. indicating that the instantaneous hazard is distributed uniformly across duration of ISD.

Fig. 3.

Yearly incidence rates of colectomy relative to transplantation. Positive values on the horizontal axis represent the number of years elapsed since OLT, and negative values correspond to the number of years remaining until OLT.

Using duration of IBD as the time variable, univariate analysis showed neither OLT nor other variables to be significant risk factors for development of colon cancer after transplantation. To control for potential confounding influences, multivariate analysis using only variables previously proposed as important risk factors for colon cancer was performed and showed that none of these variables (age at time of diagnosis of IBD, OLT, and type of immunosuppression) were significantly associated with an increased risk of cancer in this model.

The cumulative hazard of colorectal cancer as a function of duration of IBD before transplantation (dotted line) as well as for the entire IBD course (solid line) are shown in Fig. 4. In contrast to the hazard of colectomy for intractable disease (Fig. 2), the best fit for the colorectal cancer curves was an exponential function. Note that the increase of instantaneous hazard of cancer significantly depends only on the duration of IBD. Thus, OLT does not significantly change the risk of colorectal cancer.

Fig. 4.

Cumulative hazard of colorectal cancer (before transplantation and total) relative to the corresponding duration of IBD approximated by minimization of sum of squares. Exponential approximations, which had the best fit compared with other functional forms, are shown.

The analysis of colectomy because of intractable disease was repeated using several different patient cohorts in an effort to address possible clinical and statistical concerns. Neither inclusion of the 14 patients who underwent colectomy before the diagnosis of PSC nor inclusion of all patients who underwent colectomy affected the results reported. These additional analyses further substantiate the conclusion that OLT is the only significant risk factor for colectomy performed because of intractable disease.

Discussion

The natural history of IBD and the interrelationship between PSC and IBD is well documented in several large series.22,23 Colectomy is a well-accepted marker of progression of IBD, and duration of disease is the single most important risk factor for the development of colorectal cancer.24,25 Therefore, the study design and statistical methods used in our analyses follow the well-accepted biological evolution of the diseases and associated clinical end points. Missing data on colonic dysplasia is the only potential pitfall of this study, but it is not likely to significantly influence the results because the reason for colectomy was clearly documented in all cases. Moreover, we did not find any negative impact of transplantation on the ultimate expression of the colonic dysplasia (colorectal cancer). Therefore, it is very unlikely that the posttransplant immunosuppressive regimen could have affected transitional stages toward cancer.

Despite considerable cumulative experience with liver transplantation for PSC, 10,12,14,26 controversy about the course of IBD after OLT among patients with PSC is fueled by the complexity of the IBD-PSC syndrome and small size of patient cohorts available for analysis. 10,12,14 The comparatively large sample size and the statistical methodology used for the first time in this setting led us to the somewhat surprising conclusion that OLT and concomitant Use of immunosuppression accelerate progression of IBD. These results confirm the findings of some recent studies14,15 and can potentially shed new light on disease pathogenesis. Studies on experimental animals show that interleukin (IL)-10–, IL-2–, or TCR-2– deficient mice develop IBD but only after exposure to environmental organisms/antigens.27 A possible inference would be that IBD develops in genetically susceptible individuals after exposure to enteric antigens, similar to humans. In susceptible mice, aberrant hyperresponsive CD4+ T cells producing an abundance of TH1 (interferon gamma, IL- 12) or TH2 (IL-4) cytokines produce lesions similar to Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, respectively.27 Thus, it could be speculated that the immunosuppression associated with OLT might enhance the growth of enteric organisms/antigens, such as cytomegalovirus, which has recently been implicated in refractory lBD.9 Alternatively, it could be speculated that immunosuppression with calcineurin inhibitors prompts physicians to discontinue other anti-inflammatory drugs including daily treatment with corticosteroids, a practice that might potentiate IBD in some of the patients.

In contrast to earlier publications,13,18,19 this study found no significant increase in the risk of colorectal cancer after OL T. Our data show that duration of disease is the only significant risk factor for the development of colorectal cancer either before or after OL T. One possible explanation for the increased hazard of colorectal cancer found in some studies is the prolonged patient survival and duration of IBD after OL T.26 Additionally, occult malignancy at the time of transplantation cannot be excluded, particularly for patients who developed the disease shortly after transplantation. Therefore, a yearly surveillance colonoscopy is recommended for patients with long-standing IBD before and after OLT.

In conclusion, this study shows that hepatic transplantation accelerates progression of IBD in patients with PSC but poses no additional risk for the development of colorectal cancer other than that determined solely by duration of IBD. In addition, the negative impact of OLT and possibly of the use of immunosuppression on the course of IBD suggests that nonautoimmune mechanisms might well contribute to the IBD-PSC syndrome. Current controversies over the course of IBD after OLT may be resolved by use of statistical methodology that takes into account the simultaneous effects of multiple time-dependent factors on the outcome of interest.

Abbreviations

- PSC

primary sclerosing cholangitis

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- OLT

orthotopic liver transplantation

- IL

interleukin

References

- 1.Chapman RW. The colon and PSC: new liver, new danger? Gut. 1998;43:595–596. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.5.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abu-Elmagd KM, Malinchoc M, Dickson ER, Fung JJ, Murtaugh PA, Langworthy AL, Demetris AJ, et al. Efficacy of hepatic transplantation in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993;177:335–344. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lichtiger S, Present DH, Kornbluth A, Gelernt I, Bauer J, Galler G, Michelassi F, et al. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1841–1845. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406303302601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanauer SB, Smith MB. Rapid closure of Crohn’s disease fistulas with continuous intravenous cyclosporine. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:646–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Present DH, Lichtiger S. Efficacy of cyclosporine in treatment of fistulae of Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:374–380. doi: 10.1007/BF02090211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ierardi E, Principi M, Rendina M, Francavilla R, Ingrosso M, Pisani A, Amotuso A, et al. Oral tacrolimus (FK 506) in Crohn’s disease complicated by fistulae of the perineum. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:200–202. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200003000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lowry PW, Weaver AL, Tremaine WJ, Sandborn WJ. Combination therapy with oral Tacrolimus (FK506) and azathioprine or 6-mercaptop urine for treatment-refractory Crohn’s disease perianal fistulae. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1999;5:239–245. doi: 10.1097/00054725-199911000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fellermann K, Ludwig D, Stahl M, David-Walek T, Stange EF. Steroid-unresponsive acute attacks of inflammatory bowel disease: immunomodulation by tacrolimus (FK506) Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1860–1866. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.539_g.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cottone M, Pietrosi G, Martorana G, Casa A, Pecoraro G, Oliva L, Orlando A, et al. Prevalence of cytomegalovirus infection in severe refractory ulcerative and Crohn’s colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:773–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gavaler JS, Delemos B, Belle SH, Heyl AE, Tarter RE, Starzl TE, Gavaler C, et al. Ulcerative colitis disease activity as subjectively assessed by patient-completed questionnaires following orthotopic liver transplantation for sclerosing cholangitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:321–328. doi: 10.1007/BF01318204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stephens J, Goldstein R, Crippin J, Husberg B, Holman M, Gonwa TA, Klintmalm G. Effects of orthotopic liver transplantation and immunosuppression on inflammatory bowel disease in primary sclerosing cholangitis patients. Transplant Proc. 1993;25:1122–1123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaked A, Colonna JO, Goldstein L, Busuttil RW. The interrelation between sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis in patients undergoing liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 1992;215:598–605. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199206000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Narumi S, Roberts JP, Emond JC, Lake J, Ascher NL. Liver transplantation for sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 1995;22:451–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papatheodoridis GV, Hamilton M, Mistry PK, Davidson B, Rolles K, Burroughs AK. Ulcerative colitis has an aggressive course after orthotopic liver transplantation for primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut. 1998;43:639–644. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.5.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miki C, Harrison JD, Gunson BK, Buckels JA, McMaster P, Mayer AD. Inflammatory bowel disease in primary sclerosing cholangitis: an analysis of patients undergoing liver transplantation. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1114–1117. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Befeler AS, Lissoos TW, Schiano TD, Conjeevaram H, Dasgupta KA, Millis JM, Newell KA, et al. Clinical course and management of inflammatory bowel disease after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1998;65:393–396. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199802150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knechtle SJ, D’Alessandro AM, Harms BA, Pirsch JD, Belzer FO, Kalayoglu M. Relationships between sclerosing cholangitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and cancer in patients undergoing liver transplantation. Surgery. 1995;118:615–619. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loftus EV, Jr, Aguilar HI, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Krom RA, Zinsmeister AR, Graziadei IW, et al. Risk of colorectal neoplasia in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis following orthotopic liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1998;27:685–690. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bleday R, Lee E, Jessurun J, Heine J, Wong WD. Increased risk of early colorectal neoplasms after hepatic transplant in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:908–912. doi: 10.1007/BF02050624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higashi H, Yanaga K, Marsh JW, Tzakis A, Kakizoe S, Starzl TE. Development of colon cancer after liver transplantation for primary sclerosing cholangitis associated with ulcerative colitis. Hepatology. 1990;11:477–80. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840110320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sahai H, Khurshid A. Methods, Techniques, and Applications. New York: CRC Press; 1996. Statistics in Epidemiology. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brenrnall TA, Haggitt RC, Rabinovitch PS, Kimmey MB, Bronner MP, Levine DS, Kowdley KY, et al. Risk and natural history of colonic neoplasia in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:331–338. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8566577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D’Haens GR, Lashner BA, Hanauer SB. Pericholangitis and sclerosing cholangitis are risk factors for dysplasia and cancer in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1174–1178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenstein AJ, Sachar DB, Smith H, Pucillo A, Papatestas AE, Kreel I, Geller SA, et al. Cancer in universal and left-sided ulcerative colitis: factors determining risk. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:290–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katzka I, Brody RS, Morris E, Katz S. Assessment of colorectal cancer risk in patients with ulcerative colitis: experience from a private practice. Gastroenterology. 1983;85:22–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papatheodoridis GV, Hamilton M, Rolles K, Burroughs AK. Liver transplantation and inflammatory bowel disease. J Hepatol. 1998;28:1070–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80359-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rennick DM, Fort MM. Lessons from genetically engineered animal models XII. IL-10-deficient (IL-10−/−) mice and intestinal inflammation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;278:G829–G833. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.278.6.G829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]