Abstract

Paclitaxel (Taxol) is a microtubule-stabilizing compound that is used for cancer chemotherapy. However, Taxol administration is limited by serious side effects including cardiac arrhythmia, which cannot be explained by its microtubule-stabilizing effect. Recently, neuronal calcium sensor 1 (NCS-1), a calcium binding protein that modulates the inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (InsP3R), was described as a binding partner of Taxol and as a substrate of calpain. We examined calcium signaling processes in cardiomyocytes after treatment with Taxol to investigate the basis of Taxol-induced cardiac arrhythmia. After treating isolated neonatal rat ventricular myocytes with a therapeutic concentration of Taxol for several hours live cell imaging experiments showed that the frequency of spontaneous calcium oscillations significantly increased. This effect was not mimicked by other tubulin-stabilizing agents. However, it was prevented by inhibiting the InsP3R. Taxol treated cells had increased expression of NCS-1, an effect also detectable after Taxol administration in vivo. Short hairpin RNA mediated knock down of NCS-1 decreased InsP3R dependent intracellular calcium release, whereas Taxol treatment, that increased NCS-1 levels, increased InsP3R dependent calcium release. The effects of Taxol were ryanodine receptor independent. At the single channel level Taxol and NCS-1 mediated an increase in InsP3R activity. Calpain activity was not affected by Taxol in cardiomyocytes suggesting a calpain independent signaling pathway. In short, our study shows that Taxol impacts calcium signaling and calcium oscillations in cardiomyocytes through NCS-1 and the InsP3R.

Keywords: calcium, InsP3R, NCS-1, paclitaxel, taxol

Introduction

Paclitaxel (Taxol) is a natural product derived from the bark of the Pacific yew tree. In the 1960s first reports about its cytotoxic effect were published and in 1979 its mechanism as a microtubule-stabilizing drug was described.[1], [2] As a standard therapeutic for the treatment of various solid cancers, e.g. adjuvant chemotherapeutic in ovarian or mammary carcinoma, it significantly reduces the rate of mortality.[3] More recently Taxol has been introduced into drug eluting coronary stents[4] in which smaller concentrations are used, enough to inhibit cell growth and therefore restenosis around the stent. The high effectiveness of Taxol as a cancer chemotherapeutic is diminished by the association with a number of side effects which lead to serious impairments in the quality of life. The heart is a major target of these side effects which include arrhythmias that can be severe enough to lead to death of the patient.[5] Other common side effects include peripheral neuropathy, hypersensitive reactions and gastrointestinal dysfunction. Initially, the broad spectrum of side effects was proposed to be based solely on the effects of Taxol on the microtubule network. The hypersensitive reaction was explained by a response to cremophor EL, the adjuvant used to dissolve the water insoluble Taxol.[6] However, neither the hypersensitivity reaction nor Taxol’s effects to stabilize the microtubule are sufficient to explain all the cardiac and neurological side effects. A better understanding of the mechanisms involved in Taxol-induced side effects would improve Taxol therapy.

Previously, studies on the effects of Taxol on calcium signaling and signal transduction in peripheral neuronal cells were performed as an approach to address polyneuropathy.[7, 8] These studies advanced after neuronal calcium sensor 1 (NCS-1), also known as frequenin, was found to be a novel Taxol binding protein.[7] NCS-1 is a high-affinity, low-capacity calcium binding protein which contains four EF-hand motifs and positively modulates inositol-1,4,5- trisphosphate receptor (InsP3R) function by binding to the cytosolic site of this intracellular calcium release channel. It was shown in primary neuronal cells (dorsal root ganglion cells) that prolonged Taxol treatment (800 ng/mL for 6h) activated the protease calpain, resulting in decreased NCS-1 expression and reduced InsP3R dependent calcium signaling.[8] It was found that inhibition of calpain maintained NCS-1 levels and intracellular calcium signaling [8] and protected Taxol treated mice from developing polyneuropathy.[9]

Calcium is a second messenger that is involved in many cellular processes such as signal transduction, regulation of gene and protein expression, cell differentiation and cell death and is therefore important for many aspects of the maintenance of cellular homeostasis.[10] In the myocardium, calcium has a very crucial role; it is not only important in generating contractions (excitation-contraction (EC)-coupling), but also in regulating gene transcription (excitation-transcription (ET)-coupling). The diversity of roles for calcium in the heart lends support to the idea that calcium plays a key role in the development of arrhythmias where many calcium dependent mechanisms may be involved. Therefore, we examined calcium signaling processes in cardiomyocytes after the treatment with Taxol to investigate the basis of Taxol-induced cardiac arrhythmia.

We found that Taxol treatment of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes caused an increase in the frequency of spontaneous calcium oscillations. This effect was Taxol specific and not due to its influence on microtubules. The increase in calcium oscillation frequency could be prevented by inhibiting the InsP3R, indicating that the InsP3R is a crucial component in modulating calcium oscillations in cardiomyocytes. Moreover, Taxol induced an elevation in NCS-1 expression levels and increased InsP3R dependent intracellular calcium release, an effect that is opposite to its effect in neuronal cells. Taken together, our experiments suggest that Taxol was able to increase calcium oscillations in cardiomyocytes by modulating the InsP3R through its interaction with NCS-1.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

All procedures for animal use were in accordance with guidelines approved by the Yale University Animal Care and Use Committee. Isolation of neonatal rat ventricular cardiomyocytes was performed as previously described.[11] Although the purity of the cardiomyocyte culture was >95%, 25 μmol/L 5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (Sigma Aldrich) was added to inhibit growth of possible fibroblasts.

Treatment of animals with Taxol

C57bl6 mice were injected with 60 mg/kg Taxol i.p. (Sigma Aldrich) and sacrificed 6h after injection. After dry ice/CO2 anesthesia, hearts were extracted and lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Plasmids and transfection

NCS-1 and scrambled shRNA expressing vectors were used as described previously.8 Cells were transfected on the second day after culture using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. After transfection for 4h in OptiMEM (Invitrogen), complete growth medium was added for incubation overnight.

Live cell imaging

Cells plated on coverslips were incubated in Hepes buffer (145 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L KCl, 1 mmol/L MgCl2, 2.6 mmol/L CaCl2, 10 mmol/L Hepes, 5.6 mmol/L glucose; pH 7.4) containing 0.1% Pluronic F-127 and 5 μmol/L fluo-4/AM or 6 μmol/L Rhod-2/AM (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen), respectively. After 30 minutes incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2, coverslips were mounted in a chamber placed on a Zeiss LSM 510 NLO laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with Plan-Neofluar 20x/0.75 and Plan-Apochromat 63x/1.4 oil immersion objectives (Zeiss). Drugs were applied in the bath which was either calcium containing Hepes buffer (described above) or calcium-free Hepes buffer (145 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L KCl, 3 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L EGTA, 10 mmol/L Hepes, 5.6 mmol/L glucose; pH 7.4 ). A cell was considered to oscillate when at least four calcium transients (20% increase of fluorescence) were recorded over 5 minutes. An algorithm written in Matlab[12] was used to perform oscillation analysis.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

Preparation of lysates, immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting were performed as previously described.[13] The following antibodies were used in the dilutions indicated: NCS-1 1:1000 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), InsP3R type 1, 2 and 3,[13] RyR 1:500 (Affinity BioReagents), m-calpain 1:1000 (Abcam), ß-actin 1:2500 and GAPDH-HRP 1:2000 (Abcam). Secondary antibodies (BioRad) were applied in a dilution of 1:30000 for 1h at room temperature. Blots were quantified by using UN-SCAN-IT (Silk Scientific Corporation) where protein expression was normalized to ß-actin or GAPDH.

Bilayer experiments

InsP3R channel activity was monitored as described before.[14] Briefly, planar lipid bilayers were formed by painting a solution of phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylserine (5:2:3) across the 200 μm aperture of a polystyrene cup separating two compartments, cis (corresponding to the cytosol) and trans (corresponding to the lumen of the ER). Then microsomes made from mice cerebella (protocol as previously described[14]) were incorporated into the bilayer. Channel openings were initiated by addition of 2 μmol/L InsP3 into the cis side and then monitored after addition of NCS-1 and Taxol. The recording time for each added component was at least 3 minutes.

Cell viability and calpain activity assays

Cell viability was determined by using the TOX-2 kit (Sigma Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Calpain activity assay was performed using a calpain-Glo protease assay (Promega) as described previously.[8]

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the mean±SEM of n cells. Comparisons between 2 groups were performed with Student’s t-test (SigmaPlot). Statistical significance is indicated: P < 0.05 as *; P < 0.01 as ** and P < 0.001 as ***.

Results

Taxol treatment increases the spontaneous calcium oscillation frequency in cardiomyocytes

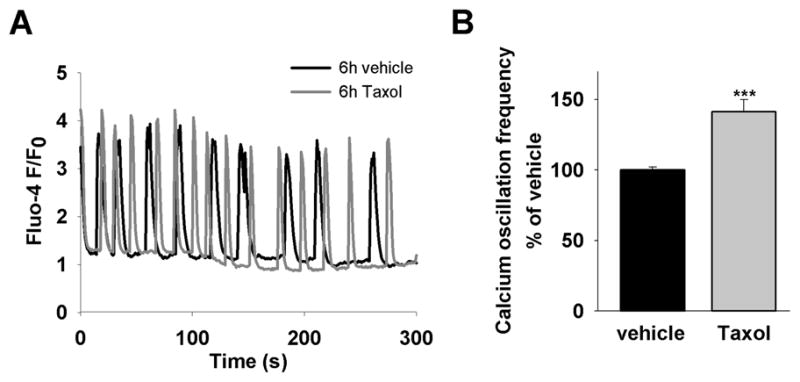

Because Taxol treatment induces cardiac arrhythmias[5] and because there were changes in intracellular calcium signaling in neurons after administration of Taxol,[7, 8] we hypothesized that Taxol treatment would also cause alterations in cardiomyocytes. When intracellular calcium changes in cardiomyocytes were monitored in a calcium containing environment, characteristic spontaneous calcium oscillations were observed.[11] We performed live cell imaging using the fluorescent calcium sensitive dye fluo-4/AM. Acute addition of 800 ng/mL Taxol to isolated neonatal rat ventricular myocytes had no effect on the baseline calcium oscillations (Supplementary Fig. 1). A concentration of Taxol of 800 ng/mL was used throughout the study as it is comparable to concentrations used in treatment of human patients and because it was shown to be the lowest concentration needed to generate a near maximal effect in previous experiments.[7, 8] Prolonged Taxol treatment for 6h led to a significant increase in the frequency of spontaneous calcium oscillations (141±9%, n=53) compared to vehicle control (100±2%, n=130, p<0.001) (Fig. 1A and B).

Figure 1. Taxol increases spontaneous calcium oscillation frequency in cardiomyocytes.

(A) Representative traces of spontaneous calcium oscillations in cells treated for 6h with vehicle (black line) or Taxol (grey line). (B) The average calcium oscillation frequency is significantly higher in Taxol treated cells (58±5 ms−1, n=130) compared to vehicle (40±1 ms−1, n=53), in the graph shown in percentage (141±9% compared to 100±2%), p<0.001.

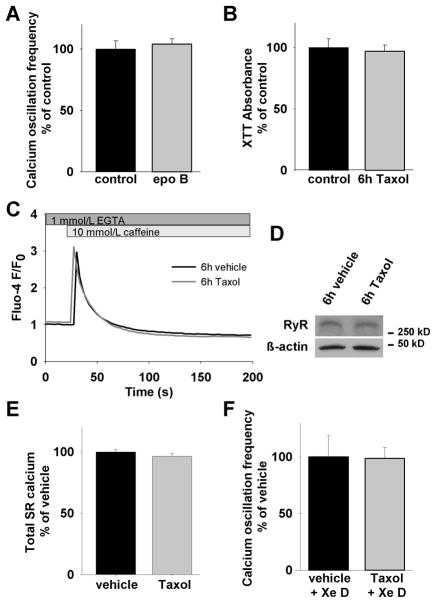

In order to see if this change was due to the microtubule-stabilizing characteristics of Taxol, we treated the cardiomyocytes for 6h with 50 ng/mL epothilone B, a comparable microtubule-stabilizing agent with the same microtubule binding site, but approximately 10 times higher efficacy.[15] In this case, we observed no alterations in the spontaneous calcium oscillation frequency (104±4%, n=34) compared to control (100±7%, n=88) demonstrating that Taxol’s impact on calcium oscillations is not caused by its effects on the microtubule network (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. Taxol-induced increase of calcium oscillation frequency is InsP3R dependent.

(A) 6h treatment with 100 nmol/L epothilone B, another microtubule stabilizing drug, in a comparable amount does not alter the frequency of spontaneous calcium oscillations (104±4%, n=34 compared to 100±7%, n=88), suggesting a Taxol-specific effect. (B) Viability of cells is not impaired after 6h Taxol treatment. (C) Taxol does not change RyR function. Treated and vehicle treated cells do not show any difference in calcium response upon stimulation with the RyR agonist caffeine. (D) RyR expression levels are unchanged after Taxol treatment. (E) The total amount of sarcoplasmic calcium is not altered (96.5 ± 1.7%, n=45 (Taxol treated) compared to 100 ± 2.4%, n=58 (vehicle treated), p=0.22). (F) With the application of xestospongin D, a potent InsP3R blocking agent, the difference in the calcium oscillation frequency between Taxol treated and vehicle treated cells can be prevented (98±10%, n=38 compared to 100±19%, n=19). This demonstrates the importance of the InsP3R in modulating calcium oscillations in cardiomyocytes.

Taxol has been shown to be able to induce apoptosis in a variety of cells.[16] To exclude the possibility that the Taxol evoked changes in calcium oscillation frequency were due to apoptotic processes, we tested cell viability by spectrometric measurement of XTT formation, an indicator of the metabolic activity in the cell. Taxol treatment for 6h did not alter the magnitude of XTT formation which showed that cell viability was not impaired (Fig. 2B).

Taxol-induced increase of calcium oscillation frequency is InsP3R dependent

In cardiomyocytes the efflux of calcium from the SR into the cytosol depends mainly on the integrity of calcium release though the ryanodine receptor (RyR). It was therefore important to study if RyR function was altered by Taxol. We performed live cell imaging experiments in a calcium-free extracellular solution (0 calcium, 1 mmol/L EGTA) to exclude calcium influx across the plasma membrane. Intracellular calcium transients were stimulated by the RyR agonist caffeine (10 mmol/L). No difference in the shape of calcium responses between Taxol and vehicle treated cells could be observed indicating that RyR-dependent calcium signaling is unaffected by Taxol treatment (Fig. 2C). Moreover, as 10 mmol/L caffeine is sufficient to deplete SR calcium in cardiomyocytes,[17] we determined the amplitude of calcium release which revealed that the amount of SR calcium was not affected by Taxol treatment (Fig. 2E). To validate our conclusion that the SR calcium store is unaffected by Taxol treatment, we depleted SR stores by adding 10 μM of the SR-ATPase (SERCA)-inhibitor thapsigargin in calcium-free medium (0 Ca2+ plus 1 mM EGTA in extracellular solution). Neither peak calcium release upon thapsigargin addition nor SR-calcium content calculated as area under the release curve differed in Taxol treated and untreated cells (data not shown). Furthermore, we performed immunoblotting showing that there was no change in the amount of RyR expression between treated and untreated cells (Fig. 2D). Likewise, RyR expression levels were unaltered in the myocardium of in vivo Taxol treated adult mice (not shown).

To further investigate the role of the InsP3R, we incubated cells in xestospongin D, a potent inhibitor of the InsP3R, prior to recording. Calcium oscillations were still apparent after inhibiting InsP3Rs with xestospongin D, indicating that the generation of calcium oscillations is not dependent on this calcium channel. However, inhibition of InsP3Rs in both Taxol treated and untreated cells abolished the difference in the frequency of calcium oscillations (Fig. 2F).

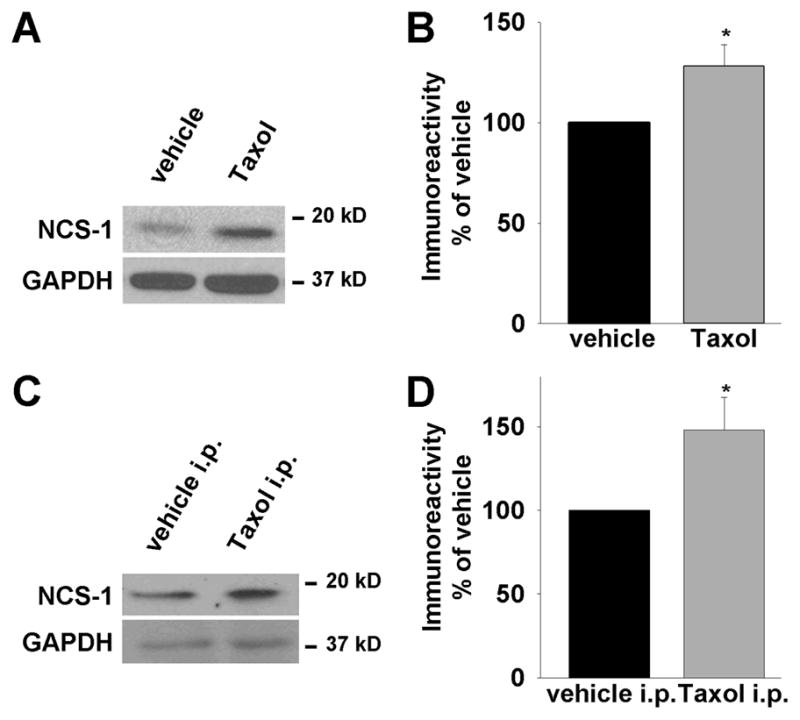

Taxol increases NCS-1 expression levels in cardiomyocytes

NCS-1 is a binding partner of the InsP3R[18] and Taxol[7] and is expressed in neonatal and adult cardiac muscle.[19] Therefore, we next examined NCS-1 levels in cardiomyocytes with and without Taxol treatment. Cardiomyocytes were isolated and then incubated with 800 ng/mL Taxol. After 6h, cells were lysed and NCS-1 expression levels were determined by immunoblotting. Densitometry analysis revealed a Taxol-specific increase of NCS-1 protein levels to 127±11% (p<0.05, n=13) compared with control cells treated with the vehicle (Fig. 3A and B). The purity of the cardiomyocyte culture with the protocol used in this study exceeds 95%.[11] A small contamination with cardiac fibroblasts might have biased the changes in NCS-1 expression levels. In order to address this issue NCS-1 levels in cardiac fibroblasts were measured. We found that cardiac fibroblasts express NCS-1 at levels much lower than that of the cardiomyocytes which suggests that an influence on the results by these cells is unlikely (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 3. Taxol treatment increases NCS-1 expression levels in neonatal cardiomyocytes and adult myocardium.

(A) Representative western blot shows increased NCS-1 expression after 6h of Taxol (800 ng/mL) treatment, whereas GAPDH expression (loading control) is unchanged. (B) Quantification of NCS-1 immunoreactivity normalized to loading control shows significant increase to 128±11% (n=13), p<0.05. (C) In vivo. Representative western blot of heart ventricles derived from mice injected with Taxol i.p. 6h prior to sacrifice reveals a Taxol-induced increase of NCS-1 immunoreactivity. (D) The increase of NCS-1 expression after Taxol treatment in vivo is increased to 148±20% (n=4), p<0.05.

NCS-1 expression is also increased in the myocardium of in vivo treated adult mice

In order to determine whether the effects of Taxol on NCS-1 levels also occurred in vivo, adult mice were injected with Taxol i.p. Hearts were retrieved 6h after injection and the ventricular portion of the heart was isolated and lysed immediately. Consistent with our findings in neonatal ventricular cardiomyocytes, an increase of NCS-1 levels was detectable in the myocardium of Taxol treated adult mice (Fig. 3C and D). This result suggests that the same mechanism for Taxol’s effects on the heart occurs in adult as well as in neonatal cardiomyocytes.

NCS-1 functionally interacts with the InsP3R in cardiomyocytes

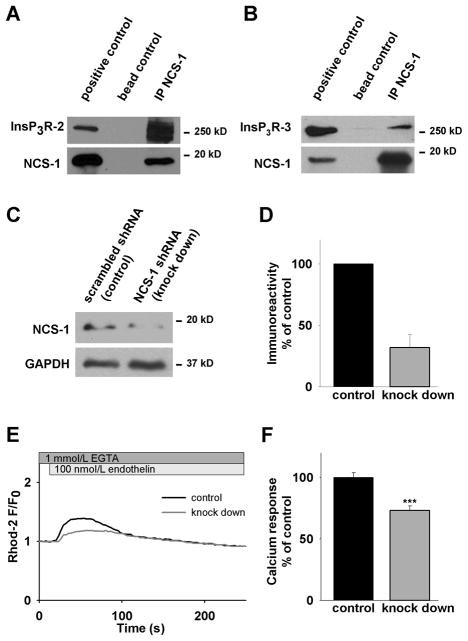

NCS-1 immunoprecipitates and functionally interacts with the InsP3R type 1.[18] Because all three isoforms of the InsP3R are expressed in neonatal cardiomyocytes,[13] we wanted to determine whether there is also an interaction between NCS-1 and the other InsP3R isoforms type 2 and 3. We performed immunoprecipitation by using anti-NCS-1 antibody and probed the precipitated sample for InsP3R type 2 and 3 with isoform specific antibodies. An interaction was observed (Fig. 4A and B) supporting the hypothesis that NCS-1 interacts with all three isoforms. This finding underlines the robustness of the InsP3R/NCS-1 interaction and suggests a (patho-) physiological importance of this interaction in the myocardium.

Figure 4. NCS-1 functionally interacts with the InsP3R in cardiomyocytes.

(A) Immunoprecipitation with anti-NCS-1 and probing with anti-InsP3R-2 specific antibody shows interaction between NCS-1 and the InsP3R-2. (B) Immunoprecipitation with anti-NCS-1 and probing with anti-InsP3R-3 specific antibody shows interaction between NCS-1 and the InsP3R-3. (C) Representative western blot of NCS-1 knock down. (D) Quantification of NCS-1 gene silencing by shRNA reveals reduced expression of the protein to 32±11% compared to cells transfected with scrambled shRNA. (E) Representative traces of calcium response to endothelin in cells transfected with NCS-1 shRNA (knock down) or scrambled shRNA (control). (F) After NCS-1 knock down, the calcium response amplitude upon endothelin stimulation is significantly reduced to 73±4% (n=15) compared to control 100±4% (n=32), p<0.001.

To further investigate the functional role of the InsP3R/NCS-1 interaction, we induced NCS-1 knock down by transient transfection with a vector co-expressing anti-NCS-1 small hairpin RNA (shRNA) and the green fluorescent protein (GFP). NCS-1 expression could be reduced to 33±10% (p< 0.005, n=3) after knock down (Fig. 4C and D). We performed live cell imaging experiments in calcium-free solution and monitored intracellular calcium transients in cardiomyocytes after stimulation with 100 nmol/L endothelin. This agonist binds to the ET-A receptor leading to the generation of InsP3 which in turn activates the InsP3R. Co-expression with GFP allowed us to identify cells expressing shRNA which contain reduced levels of NCS-1. Compared to control cells expressing scrambled shRNA, NCS-1 knock down cells showed a significantly decreased amplitude in their calcium response upon endothelin stimulation (Fig. 4E and F). This clearly demonstrates a functional role of NCS-1 in shaping InsP3R dependent calcium signaling in cardiomyocytes.

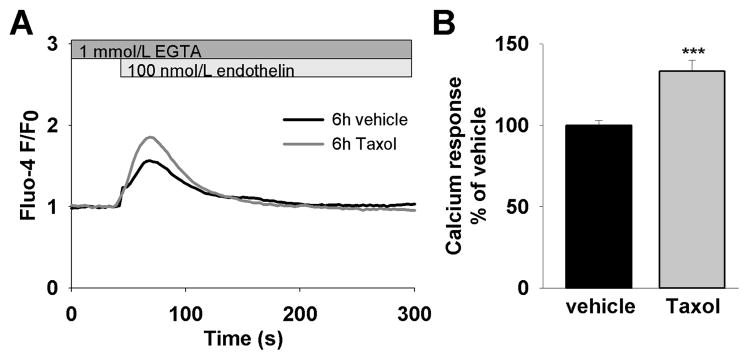

Taxol increases InsP3R dependent calcium release in cardiomyocytes

As NCS-1 functionally interacts with the InsP3R and NCS-1 levels were increased after Taxol treatment, we hypothesized that the inositol phosphate pathway is altered after Taxol treatment. Upon endothelin stimulation, cardiomyocytes treated with Taxol generated calcium transients with a significantly higher amplitude (Fig. 5A and B). To examine whether this alteration could be due to altered levels of the InsP3R we determined expression of the InsP3R by western blot analysis. There was no difference in protein expression in any of the 3 InsP3R isoforms when comparing Taxol treated and control cardiomyocytes (Supplementary Fig. 3A, B and C). We also examined InsP3R levels in the myocardium of in vivo treated adult mice. Again, InsP3R expression levels were not changed after Taxol treatment (not shown) showing the similarity between neonatal and adult cardiac cells in this parameter. Taken together, the observed Taxol-induced enhancement of InsP3 mediated calcium response appears not to be caused by an alteration of InsP3R expression levels, but instead due to a modulation of the InsP3R function by NCS-1.

Figure 5. Taxol increases InsP3R dependent calcium release.

(A) Representative calcium response to endothelin stimulation of cells treated with either vehicle or 800 ng/mL Taxol for 6h. (B) The average response amplitude is significantly higher in cells treated with Taxol (133±3%, n=69) compared to vehicle (100±7%, n=105), p<0.001.

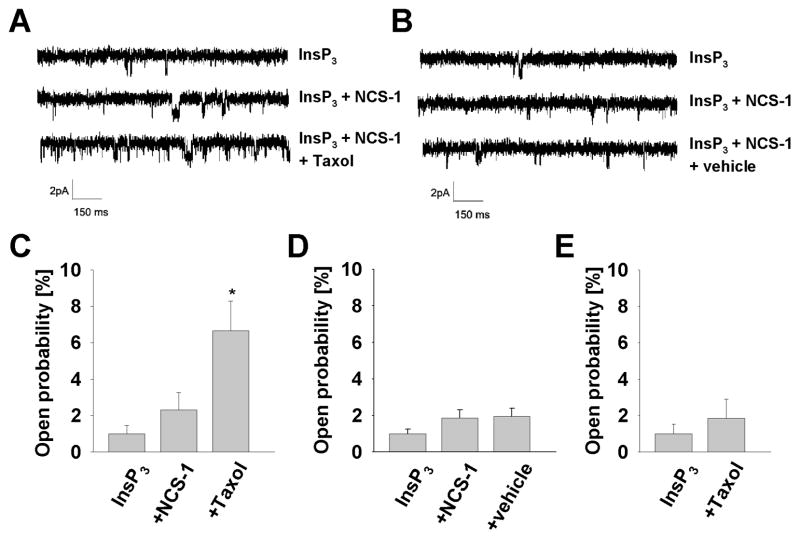

Taxol increases InsP3R activity through NCS-1

Lipid bilayer experiments were performed to determine the influence of Taxol on the InsP3R at the single channel level. After incorporation into the bilayer, the InsP3R was activated by addition of ATP, free calcium and InsP3 to the cytoplasmic side. When 800 ng/mL Taxol was added to the cytoplasmic side of the channel there was no change in channel activity. The lack of difference between channel activity before and after adding Taxol suggests that Taxol has no direct influence on the InsP3R (Fig. 6E). However, the result was different when NCS-1 was present - addition of Taxol in the presence of NCS-1 significantly increased InsP3R activity (6.7±1.6%, p<0.05, n=4) (Fig. 6A and C). In control experiments, addition of the vehicle had no effect on channel activity even in the presence of NCS-1 (Fig. 6B and D). The mean open time was not significantly elevated in the experiments (not shown) suggesting that the effect of Taxol is on the ability to open the channel, rather than on the duration of channel openings. These findings clearly show that Taxol increases the InsP3R opening frequency approximately 3 fold in the presence of NCS-1 and support the interpretation of the studies on the isolated cardiomyocytes described above.

Figure 6. Taxol increases InsP3R activity through NCS-1.

(A) Representative traces of single channel recordings of the InsP3R in lipid bilayer after adding 2 μmol/L InsP3, 0.5 μg/mL NCS-1 and 800 ng/mL Taxol in the presence of free calcium (pK 7.0). Results are quantified and normalized to baseline in (C), showing that the channel open probability is enhanced from 2.3±1.0% (n=4) to 6.7±1.6% (n=4) by Taxol, p<0.05. (B) and (D) In contrast, recordings reveal no significant difference with adding the corresponding amount of the vehicle in the control experiment. (E) Addition of Taxol without the presence of NCS-1 does not evoke any significant change in the channel activity either, confirming that the effect of Taxol on the InsP3R is mediated through NCS-1.

Taxol treamtment does not lead to calpain activation and subsequent NCS-1 degradation in cardiomyocytes

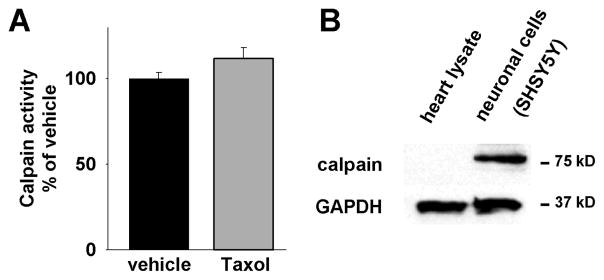

NCS-1 was described as a substrate of the protease calpain and in neuronal cells Taxol led to calpain activation and subsequent NCS-1 degradation.[8] In order to examine Taxol’s influence on calpain in cardiomyoctes, we determined calpain activity with and without Taxol treatment. Because the previous findings in neurons were opposite to the increase in NCS-1 observed in Taxol treated cardiomyocytes shown above, the results in cardiomyocytes were expected to diverge from those obtained using neurons. Indeed, no significant difference in calpain activity was seen when comparing Taxol treated (112±6%, n=7) and untreated cells (100±2%, n=8) (Fig. 7A). To further investigate the role of calpain, we examined expression levels of μ- and m-calpain, the two most intensely studied calpains and both expressed in the heart. It was reported that expression of μ-calpain rapidly diminishes in ventricular cadiomyocytes in the early postnatal period and is down-regulated in the heart.[20] Consistent with this observation, we found that m-calpain is also expressed in the myocardium at very low levels (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7. Taxol does not lead to calpain activation.

(A) Calpain activity in cardiomyocytes is not significantly changed after 6h Taxol treatment compared to vehicle treatment. (B) Representative western blot showing that calpain expression is significantly less in cardiomyocytes compared to neurons.

Discussion

In this study we investigated the effects of Taxol on the heart by examining possible disturbances in calcium signaling in neonatal ventricular cardiomyocytes. We report that the frequency of spontaneous calcium oscillations in cardiomyocytes was significantly increased after Taxol treatment. This finding is potentially important because changes in calcium homeostasis have been linked to arrhythmogenesis.[21] For example, it was shown in Guinea pig heart that spontaneous calcium oscillations can manifest as premature beats, ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation.[22]

The effect on calcium oscillations was not caused by the microtubule polymerizing characteristics of Taxol, an altered SR calcium store or impaired cell viability. We could exclude the RyR as the key player for this effect as neither RyR dependent calcium signaling nor RyR expression was changed. Interestingly, the InsP3R seemed to be of importance as inhibition of this SR channel abolished Taxol’s effect on calcium oscillations.

We examined expression of NCS-1, a known modulator of the InsP3R and a binding protein of Taxol. NCS-1 expression levels in cardiomyocytes were increased upon Taxol treatment. Knock down of NCS-1 decreased InsP3R dependent intracellular calcium release, whereas Taxol treatment that increased NCS-1 levels increased InsP3R dependent calcium release. As these observations were not due to changes in InsP3R protein expression, we concluded that these effects were due to a modulation of the InsP3R. Experiments to monitor Taxol’s effect on the InsP3R at the single channel level showed that Taxol enhanced channel activity in the presence of NCS-1. This result demonstrates on the molecular level that Taxol is able to modulate InsP3R activity through NCS-1. It is consistent with the idea that Taxol’s interaction with NCS-1 increases the binding between NCS-1 and the InsP3R.[8] Taken together, our studies suggest that Taxol increases NCS-1 mediated InsP3R channel openings which, in addition to increased NCS-1 levels due to chronic Taxol treatment, results in more frequent calcium release. This situation triggers more SR calcium release and subsequently leads to faster calcium oscillations in the cell.

The difference in NCS-1 expression levels between neurons and cardiomyocytes after Taxol treatment is remarkable and underscores the diversity of these cell types. It was shown in neuronal cells that prolonged treatment with Taxol caused an activation of the calcium dependent protease calpain. As a result, NCS-1 as a calpain substrate was decreased which led to an impaired InsP3R dependent calcium signaling.[8] In contrast to the decreased NCS-1 levels in neuronal cells, Taxol induced an increase in NCS-1 expression in neonatal ventricular cardiomyocytes and adult myocardium. This study showed that calpain activity in cardiomyocytes is not significantly altered after Taxol treatment. Expression of m-calpain as well as μ-calpain is significantly less in the myocardium when compared to neuronal cells. The large difference in calpain protein expression levels between those two cell types and the subsequent effect, or lack thereof, on calpain activation, is a likely explanation for the difference in NCS-1 protein expression levels after Taxol treatment. Furthermore, as Taxol increases binding of NCS-1 to the InsP3R, it is conceivable that bound NCS-1 is less likely to be degraded which in consequence would result in higher NCS-1 levels.

In an earlier study, hearts treated with 5 μmol/L Taxol had an increased probability of eliciting stretch-induced arrhythmia whereas hearts treated with colchicine showed no statistically significant change.[23] Taxol was assumed to act solely as a microtubule-stabilizing agent and the authors concluded that the proliferation of microtubules increased the arrhythmogenic effect of transient left ventricle diastolic stretch.[23] It should also be noted that the previous study used a concentration of Taxol more than 5 times higher than the concentrations used in the present study. Our findings show that Taxol has functional effects on cellular components in addition to the stabilizing effects on the microtubule apparatus and provide a different explanation for the effect of Taxol on the occurrence of treatment associated ventricular arrhythmias.

Because adult and neonatal cardiomyocytes have differences in their biochemical characteristics, pattern of protein expression and physiological responses, in part due to their different degree of differentiation, it can be difficult to make conclusions about the function of adult cardiomyocytes from results obtained using neonatal cells. However, freshly isolated adult myocytes need to be used within a few hours after isolation which limits the usefulness of this model system in the current study due to the prolonged Taxol incubation time. Also, adult myocytes begin to develop mechanisms in maintaining calcium haemostasis similar to those seen in neonatal myocytes within hours in culture.[24] Our in vivo experiments investigating Taxol’s effects on NCS-1 levels in adult myocardium revealed comparable results to neonatal cardiomyocytes. Therefore, it is likely that Taxol has similar functional effects in neonatal and adult cardiomyocytes and that neonatal cardiomyocytes are a valid model for this type of study.

Taxol activates the calcium sensitive transcription factor nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) in various tumor cell lines.[25] It was shown that ventricular up-regulation of NF-κB is related to ventricular arrhythmia in cardiomyopathic myocardium and that both arrhythmia and NF-κB up-regulation are suppressed by selective ET-A receptor blockade.[26] Moreover, it was shown in the hypertrophic heart that NF-κB is activated[27] through increased InsP3R dependent calcium release.[13] Based on this body of evidence and our observations that Taxol increases endothelin evoked InsP3R dependent calcium release, it is reasonable to propose the existence of a calpain independent and NF-κB dependent NCS-1/InsP3R signaling pathway in Taxol-induced cardiac arrhythmia. NF-κB functions as a key regulator of cardiac gene expression programs downstream of multiple signal transduction cascades in a variety of physiological and pathophysiological states. In this context, NF-κB may be influenced in a calcium dependent manner[28] downstream of the NCS-1 signaling cascade as well as it may regulate NCS-1 gene expression in a feedback loop. Further studies are needed for a detailed description of the underlying signaling pathway.

In summary, we have shown that prolonged Taxol treatment enhances spontaneous calcium oscillations in ventricular cardiomyocytes. In contrast to neuronal cells, Taxol increases NCS-1 levels in cardiomyocytes which leads to increased InsP3R dependent calcium release from intracellular stores of calcium. Taken together, this study provides new insights into the pathomechanism of Taxol in the heart, where NCS-1 and the InsP3R are the primary players and Taxol enhances their interaction to increase calcium signaling and calcium oscillations in cardiomyocytes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Yung-Chi Cheng and Sven-Eric Jordt for the support with the animal studies. We thank Craig Gibson, Andjelka Celic for thoughtful discussions and comments on the manuscript. We also like to thank Xiao Bai, Tatjana Coric and Dawidson Gomes for their kind help. We are grateful to Richard Wojcikiewicz for generously providing the InsP3R type 2 antibody and Andreas Jeromin for providing shRNA for NCS-1.

Sources of funding

This work was supported by grants from the NIH to BEE (DK57751, DK61747) and German National Merit Foundation scholarships (KZ, FMH, WB).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Walsh V, Goodman J. Cancer chemotherapy, biodiversity, public and private property: the case of the anti-cancer drug taxol. Social science & medicine (1982) 1999 Nov;49(9):1215–25. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00161-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiff PB, Fant J, Horwitz SB. Promotion of microtubule assembly in vitro by taxol. Nature. 1979;277(5698):665–7. doi: 10.1038/277665a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rowinsky EK. Paclitaxel pharmacology and other tumor types. Seminars in oncology. 1997 Dec;24(6 Suppl 19):S19-1–S-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woods TC, Marks AR. Drug-eluting stents. Annual review of medicine. 2004;55:169–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.55.091902.105243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rowinsky EK, McGuire WP, Guarnieri T, Fisherman JS, Christian MC, Donehower RC. Cardiac disturbances during the administration of taxol. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9(9):1704–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.9.1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gelderblom H, Verweij J, Nooter K, Sparreboom A. Cremophor EL: the drawbacks and advantages of vehicle selection for drug formulation. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(13):1590–8. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boehmerle W, Splittgerber U, Lazarus MB, McKenzie KM, Johnston DG, Austin DJ, et al. Paclitaxel induces calcium oscillations via an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor and neuronal calcium sensor 1-dependent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(48):18356–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607240103. Epub 2006 Nov 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boehmerle W, Zhang K, Sivula M, Heidrich FM, Lee Y, Jordt SE, et al. Chronic exposure to paclitaxel diminishes phosphoinositide signaling by calpain mediated NCS-1 degradation in neuronal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701546104. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang MS, Davis AA, Culver DG, Wang Q, Powers JC, Glass JD. Calpain inhibition protects against Taxol-induced sensory neuropathy. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 3):671–9. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh078. Epub 2004 Feb 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clapham DE. Calcium signaling. Cell. 2007 Dec 14;131(6):1047–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uhlen P, Burch PM, Zito CI, Estrada M, Ehrlich BE, Bennett AM. Gain-of-function/Noonan syndrome SHP-2/Ptpn11 mutants enhance calcium oscillations and impair NFAT signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(7):2160–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510876103. Epub 006 Feb 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uhlen P. Spectral analysis of calcium oscillations. Sci STKE. 2004;2004(258):pl15. doi: 10.1126/stke.2582004pl15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heidrich FM, Zhang K, Estrada M, Huang Y, Giordano FJ, Ehrlich BE. Chromogranin B regulates calcium signaling, nuclear factor kappaB activity, and brain natriuretic peptide production in cardiomyocytes. Circulation research. 2008 May 23;102(10):1230–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.166033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rengifo J, Gibson CJ, Winkler E, Collin T, Ehrlich BE. Regulation of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type I by O-GlcNAc glycosylation. J Neurosci. 2007 Dec 12;27(50):13813–21. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2069-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kowalski RJ, Giannakakou P, Hamel E. Activities of the microtubule-stabilizing agents epothilones A and B with purified tubulin and in cells resistant to paclitaxel (Taxol(R)) J Biol Chem. 1997;272(4):2534–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodi DJ, Janes RW, Sanganee HJ, Holton RA, Wallace BA, Makowski L. Screening of a library of phage-displayed peptides identifies human bcl-2 as a taxol-binding protein. J Mol Biol. 1999;285(1):197–203. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu X, Bers DM. Sarcoplasmic reticulum and nuclear envelope are one highly interconnected Ca2+ store throughout cardiac myocyte. Circulation research. 2006 Aug 4;99(3):283–91. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000233386.02708.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schlecker C, Boehmerle W, Jeromin A, DeGray B, Varshney A, Sharma Y, et al. Neuronal calcium sensor-1 enhancement of InsP3 receptor activity is inhibited by therapeutic levels of lithium. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(6):1668–74. doi: 10.1172/JCI22466. Epub 2006 May 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakamura TY, Sturm E, Pountney DJ, Orenzoff B, Artman M, Coetzee WA. Developmental expression of NCS-1 (frequenin), a regulator of Kv4 K+ channels, in mouse heart. Pediatr Res. 2003;53(4):554–7. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000057203.72435.C9. Epub 2003 Feb 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahuja P, Perriard E, Pedrazzini T, Satoh S, Perriard JC, Ehler E. Re-expression of proteins involved in cytokinesis during cardiac hypertrophy. Experimental cell research. 2007 Apr 1;313(6):1270–83. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ter Keurs HE, Boyden PA. Calcium and arrhythmogenesis. Physiological reviews. 2007 Apr;87(2):457–506. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lakireddy V, Bub G, Baweja P, Syed A, Boutjdir M, El-Sherif N. The kinetics of spontaneous calcium oscillations and arrhythmogenesis in the in vivo heart during ischemia/reperfusion. Heart Rhythm. 2006 Jan;3(1):58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parker KK, Taylor LK, Atkinson JB, Hansen DE, Wikswo JP. The effects of tubulin-binding agents on stretch-induced ventricular arrhythmias. European journal of pharmacology. 2001 Apr 6;417(1–2):131–40. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00856-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poindexter BJ, Smith JR, Buja LM, Bick RJ. Calcium signaling mechanisms in dedifferentiated cardiac myocytes: comparison with neonatal and adult cardiomyocytes. Cell calcium. 2001 Dec;30(6):373–82. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2001.0249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bergstralh DT, Ting JP. Microtubule stabilizing agents: their molecular signaling consequences and the potential for enhancement by drug combination. Cancer treatment reviews. 2006 May;32(3):166–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xia HJ, Dai DZ, Dai Y. Up-regulated inflammatory factors endothelin, NFkappaB, TNFalpha and iNOS involved in exaggerated cardiac arrhythmias in l-thyroxine-induced cardiomyopathy are suppressed by darusentan in rats. Life sciences. 2006 Oct 4;79(19):1812–9. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heineke J, Molkentin JD. Regulation of cardiac hypertrophy by intracellular signalling pathways. Nature reviews. 2006 Aug;7(8):589–600. doi: 10.1038/nrm1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dolmetsch RE, Lewis RS, Goodnow CC, Healy JI. Differential activation of transcription factors induced by Ca2+ response amplitude and duration. Nature. 1997 Apr 24;386(6627):855–8. doi: 10.1038/386855a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.