Introduction

In September 2010, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) marked the 20th anniversary of the establishment of the Office of Research on Women's Health (ORWH) with the release of a newly revised research agenda on women's health, A Vision for 2020 for Women’ Health Research: Moving into the Future with New Dimensions and Strategies (A Vision for 2020).1 This research agenda provides an outlook for scientific exploration driven by the synergy of cutting-edge technologies and novel concepts to accelerate advances in women's health and sex differences research in the coming decade through interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary collaboration. The report is the product of the collective contributions and discussions of over 1,500 individuals who participated in a series of national meetings convened at five regional locations across the United States and reflects many of the principles upon which the ORWH was founded.

A news release from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) on September 10, 1990, announced the establishment of the ORWH within the Office of the Director of the NIH as the first office within HHS that would have the health of women as its primary goal. The HHS Secretary at that time, Dr. Louis W. Sullivan, announced that, “Women's health issues need and deserve the attention and priority that this new office will give them …”2

Among its first activities the ORWH was expected to develop a plan to increase NIH-supported research on women's health by establishing NIH-wide goals and policies for research related to women's health. ORWH was also mandated to coordinate NIH activities undertaken in performing such research and to interact with the scientific and medical communities, organizations with an interest in women's health, and other components of government to inform them of NIH's programs related to women's health, identify areas of research that need emphasis, and involve them in efforts to expand and encourage research on women's health. The ORWH took this charge seriously. The first NIH agenda resulted from a public workshop held in 1991 entitled, “Opportunities for Research on Women's Health.”3 NIH has continued to incorporate outreach to advocacy organizations and public representatives with an interest in women's health along with scientific and health professional partners in determining gaps in knowledge and pathways for emphasis through research to broaden understanding about women's health and diseases. Including representatives of the NIH Institutes and Centers such that there were trans-NIH involvement and potential for implementation has further strengthened this process.

This interactive scientific and public partnership has been especially rewarding for the ORWH in each of its research agenda setting efforts and was central to plans and activities of the current national strategic planning initiative that has resulted in the introduction of this new agenda for the next decade, A Vision for 2020.

In October 2008, ORWH embarked on a process to explore and devise new dimensions and strategies for the NIH women's health research agenda for the next decade. The resulting A Vision for 2020 report is designed to capitalize on opportunities that will project women's health and sex differences research at least 10 years into the future. Following the tradition established by the ORWH from its inception, the research agenda setting process was open to the involvement of members of the public that have included women's health advocacy groups, public health officials, scientists, researchers, policymakers, clinicians, and individuals representing their own concerns or the perspectives of academia, government, and industry. Federal Register notices were issued to solicit participation of audiences not generally reached through scientific channels and resulted in unique contributions from the public at large in all aspects of the meetings.4 The Federal Register notices invited public testimony on any aspect of women's health or sex differences research and on biomedical career aspects that an individual or organization wished to present. This provided the opportunity for unscripted discussions that often brought to light new vistas of attention as well as the valuable participation of additional individuals who could then be invested in these efforts. Sponsoring scientific symposia and public hearings that are not by invitation only, but rather are open and welcoming to all who have an interest in, or stake in, the health of girls, women, their families, and their communities helps to ensure that ORWH continues to meet its original mandate and reflects the research needs expressed by both public and scientific communities to strengthen the scientific foundation for improved health and healthcare.

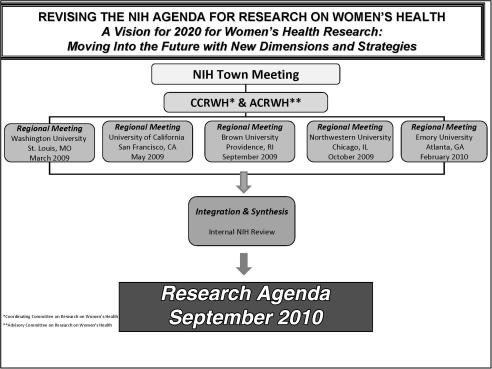

The regional public hearings and scientific workshops held in 2009 and 2010 were hosted by invitations extended to the ORWH from academic and research institutions that have or had representatives on the NIH Advisory Committee for Research on Women's Health (ACRWH), the statutory non-Federal group whose function is to advise the Director of ORWH on appropriate research activities to be undertaken by the national research institutes with respect to research on women's health.5 These included Washington University School of Medicine and Center for Women's Infectious Disease Research, St. Louis, Missouri6; University of California, San Francisco, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences, San Francisco, California7; The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University and Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island, Providence, Rhode Island8; Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine and Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago, Illinois9; and Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia10 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

A Vision for 2020 for Women's Health Research.

Stakeholders met to discuss, deliberate, and finally to draft scientific recommendations for the new research agenda based upon public testimony and scientific working group discussions. These meetings encouraged an environment for interactive discourse on future priorities and innovative scientific approaches to advancing the field of women's health and sex differences research ranging from an increased focus on sex and gender in the clinical translation of basic research findings to the impact of behavioral, psychosocial, and societal factors on health and disease. At each meeting, there were also specific presentations and working groups on biomedical career development for women, and for women and men as researchers in women's health or related efforts: Women in Biomedical Careers; Women in Science; Careers in Dentistry, Bioengineering, and other Non-Medical Disciplines; Women in Science Careers; and Women's Careers in the Biomedical Sciences.

In the design of each meeting, stakeholders were challenged to adopt an approach that was truly forward-thinking, consider creative strategies to determine areas best poised for advancement, and consider innovative ways to approach persistent issues of health and disease, keeping in mind where investigative initiatives should take science in the next decade and how best to achieve this goal. Discussants were advised to consider research that addressed not only female to male comparisons but also disparities and differences between diverse populations of women. Participants were asked to begin with what had been learned from past research, address continuing or emerging gaps in knowledge, and recommend a new framework for such research to be conducted. Participants were further instructed to take into account how new knowledge could best be integrated into health professions education and how to increase public awareness and consumer education through evolving 21st century techniques of informatics and other methods of communication. Finally, considerations were to be given to the implementation of advances in knowledge from research into health practices and public health policies that can inform aspects of healthcare reform that are specifically applicable to girls and women and their families.

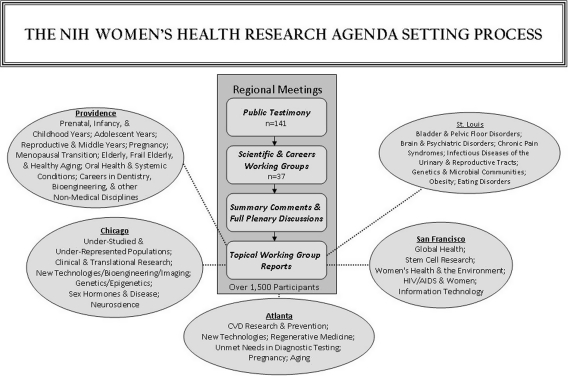

The format of each of the regional meetings was designed to promote a dynamic forum for a mutually informative and collaborative research agenda setting process (Fig. 2). Over 1,500 individuals from 33 states, Great Britain, and Australia attended these meetings, representing academic institutions, professional associations, advocacy organizations, healthcare facilities, and science policy analysts interested in research on women's health and sex/gender factors in health and disease. At least 141 advocacy and academic organizations and individuals presented oral and written testimony and were also active participants in the scientific working groups, a model that ORWH has embraced. Testimonies included personal expressions of the painful, life altering and debilitating effects of a wide range of diseases, such as autoimmune diseases, pelvic floor disorders, and chronic pain syndromes, as well as personal expressions of NIH career development programs and their beneficial effects on career advancement. The concerns and issues highlighted brought remaining gaps in knowledge and unmet needs in women's health information to the forefront and underscored the ultimate goal of the research agenda, to improve the health of women and girls and enhance career development in women's health research careers.

FIG. 2.

Research agenda setting process.

A total of 37 scientific and career development working groups were jointly co-chaired by leading extramural and NIH scientists, representing 44 academic institutions and 19 NIH Institutes and Centers and the Office of the Director. The leadership for each regional meeting was provided by extramural co-chairs with assistance of representatives of the NIH. The discussion format was intentionally informal, encouraging participants to contribute ideas and suggestions for the new research agenda. Stakeholders challenged one another to broaden the perspectives of what constitutes women's health, pushing boundaries through the rigor of systems thinking incorporating the myriad interdisciplinary perspectives offered. The resulting working group reports included a total of 400 recommendations, from which six cross-cutting goals were distilled. Central to the six goals is the importance of evaluating sex and gender differences across the research spectrum with an explicit emphasis on interdisciplinary approaches. The goals of the strategic plan are summarized below:

Goal #1: Increase the study of sex and gender differences in basic biomedical and behavioral research

This goal encompasses research in many and diverse fields of study, such as genetics, immunology, endocrinology, developmental biology, cell biology, microbiology, biochemistry, and toxicology, as well as basic and behavioral social processes. Advances in these fields will be based on new technologies, such as high-throughput sequencing, data acquisition, bioengineering, and bioinformatics, and on new modeling and data analytic techniques. Research conducted with both female and male cells, tissues, and animal model systems is paramount for developing strategies to improve clinical diagnosis and therapy. In addition, the study of the interactions of biological factors with behavioral or social variables and how they affect each other must consider sex differences as an integral part of the development of a knowledge base of how these mechanisms and processes relate to health.

Goal #2: Incorporate findings of sex and gender differences into the design and application of new technologies, medical devices, and therapeutic drugs

In clinical application, the availability of new medical devices as well as advances in bioimaging and the availability of ways to identify susceptibility genes and biomarkers of disease have revolutionized models of disease diagnosis and management. In developing and utilizing new research technologies and clinical applications, it is important that sex differences be part of their design. Some technologies are not as readily applicable to women as to men because their development and standardization have been based primarily on study of males. Furthermore, sex differences in biological response to drugs remain an underexplored area.

Goal #3: Actualize personalized prevention, diagnostics, and therapeutics for women and girls

A major goal of biomedical research is to create knowledge that will lead to more accurate strategies for diagnosis and preventive and therapeutic interventions, thereby ushering in a new era of personalized medicine. Personalized medicine considers individual differences in genetics, biology, and health history. Increasingly, it is also acknowledged that a comprehensive approach to personalized medicine must take into account biological sex and age as well as health disparities stemming from such factors as social and cultural influences.

Goal #4: Create strategic alliances and partnerships to maximize the domestic and global impact of women's health research

It would be beneficial to expand global strategic alliances and partnerships aimed at improving the health of women and girls throughout the world. Strategic alliances and partnerships with women's health stakeholders, which include NIH Institutes and Centers, other Federal agencies, academia, advocacy groups, foundations, and industry, are imperative to the success of ORWH in furthering women's health research. Collaborations resulting from these alliances will help advance research and lead to improvements in women's health, leverage resources among public and private entities, enhance public knowledge about ORWH, and strengthen support from the scientific community for ORWH's mission.

Goal #5: Develop and implement new communication and social networking technologies to increase understanding and appreciation of women's health and wellness research

Because it is important to bring important advances in all areas of science to diverse audiences, effective communication will improve health outcomes for women and girls, both for their own sake and because women throughout the world play a central role in the health of their families and communities. Communications, policy development, and implementation science must be linked effectively to achieve these outcomes. Moreover, because of cultural and racial/ethnic diversity in national and international societies and communities, information about women's health research and related issues must be disseminated in culturally and globally appropriate ways in order to educate, explain, and promote healthy behaviors and public health. Multiple media strategies, along with employing the latest communication technologies, should be considered in communications research to determine how to best reach diverse audiences on a national and global level.

Goal #6: Employ innovative strategies to build a well-trained, diverse, and vigorous women's health research workforce

Although women are well represented in early career phases of the life sciences, there is a well-recognized “leaky pipeline” that leads to the absence or underrepresentation of women in senior research leadership positions. It is therefore essential to learn from and expand upon successful efforts as well as to develop and implement innovative programs and policies that will attract, retain, and advance women throughout their scientific careers. This strategy would involve a two-pronged approach. One is to devise programs to increase and enhance the roles of women in science, research, public health policy, and health leadership to support the scientific research enterprise. The second is to ensure that both men and women researchers understand and will pursue global research that will address health issues of women and/or sex differences research and that career development programs are developed, expanded, or implemented that can facilitate sustained career advancement.

The complete research agenda is presented as a three-volume publication. Volume I, A Strategic Plan for Women's Health Research–Moving into the Future with New Dimensions and Strategies: A Vision for 2020, represents the NIH women's health research agenda for the next decade including the six overarching goals. Final reports of all 37 working groups are presented in Volume 2. The entire collection of public testimony from all regional meetings is included in Volume 3 of the research agenda.

To implement this research agenda will require collaboration among NIH, the NIH intramural and extramural scientific communities, other governmental and funding agencies, professional societies, advocacy groups, and practitioners to advance women's health research and its valuable potential for improving health and healthcare. This model of innovative research, informed by public collaboration and interdisciplinary scientific dialogue, has provided the foundation for ORWH research and career programmatic initiatives and continues to guide the future of NIH women's health research and career development efforts. The ORWH is mindful of the vital assistance of its public and professional partners in its efforts to improve the health of future generations of girls and women, and their families and communities, through the fruits of scientific investigation, and is appreciative of the thoughtful contributions of these partners in assisting ORWH in meeting its mandates.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Suzanne Medgyesi-Mitschang, Ph.D., and Joyce R. Rudick for their contributions to the development of the research agenda.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.A Vision for 2020 for Women's Health Research: Moving into the Future with New Dimensions and Strategies. NIH Publication No. 10–7606.

- 2.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Establishment of the Office of Research on Women's Health. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1990. Public Health Service. Press Release. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Report of the National Institutes of Health: Opportunities for Research on Women's Health (full report) NIH Publication No.92–3457.

- 4.Federal Register. 2009;74 , and 2010;75. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office of Research on Women's Health. Notice of Meeting: Moving Into the Future–New Dimensions and Strategies for Women's Health Research for the National Institutes of Health. Federal Register. 2009;74:6647. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Notice of Meeting: Moving Into the Future—New Dimensions and Strategies for Women's Health Research for the National Institutes of Health. Federal Register. 2009;74:18244. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Notice of Meeting: Moving Into the Future—New Dimensions and Strategies for Women's Health Research for the National Institutes of Health. Federal Register. 2009;74:38449. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Notice of Meeting: Moving Into the Future–New Dimensions and Strategies for Women's Health Research for the National Institutes of Health. Federal Register. 2009;74:42312. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Notice of Meeting: Moving Into the Future–New Dimension and Strategies for Women's Health Research for the National Institutes of Health. Federal Register. 2010;75:2553. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act of 1993. Jun 10, 1993. orwh.od.nih.gov/inclusion/revitalization.pdf. [Aug 2;2010 ]. orwh.od.nih.gov/inclusion/revitalization.pdf (Public Law 103–43), 107 Stat. 22 (codified at 42 U.S.C.§ 289.a-l),