Abstract

With the awareness of maternal depression as a prevalent public health issue and its important link to child physical and mental health, attention has turned to how healthcare providers can respond effectively. Intimate partner violence (IPV) and the use of alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs are strongly related to depression, particularly for low-income women. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends psychosocial screening of pregnant women at least once per trimester, yet screening is uncommonly done. Research suggests that a collaborative care approach improves identification, outcomes, and cost-effectiveness of care. This article presents The Perinatal Mental Health Model, a community-based model that developed screening and referral partnerships for use in community obstetric settings in order to specifically address the psychosocial needs of culturally diverse, low-income mothers.

Introduction

Depression is among the most prevalent and treatable mental health disorders. For women aged 15–44, maternal depression is the leading cause of disease burden worldwide,1 and mothering young children increases the risk of depression.2 Estimates of depression in women with children range from 10% to 42%,3–7 with few of these women either identified or treated.8–11 For many women with young children, depressive symptoms are not transient,12,13 often lasting well into their children's school years.14 Women frequently cycle between minor and major depression,15 and consequently, many children are exposed to the deleterious effects of chronic maternal depression, which include poor parenting practices, neglect, and abuse.16–18 This is an important target for prevention efforts, yet lack of identification and of treatment are significant problems despite the availability of reliable and acceptable screening and diagnostic instruments, an excellent published risk-benefit discussion, published descriptions of the problem, health provider associations' specific recommendations, and availability of effective pharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatments.19–22

Maternal Depression and Other Perinatal Risk Factors

Depression impacts low-income women disproportionately.23 Although research has begun to address issues of ethnic influences on maternal depression,12,24–28 data suggest that poverty is a powerful predictor of depression regardless of race/ethnicity.3,29–31 Intimate partner violence (IPV) and the use of alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs (ATOD) are also strongly related to depression.32 The prevalence of IPV during pregnancy is estimated to be 5.3%–8.7% around the time of birth.33,34 IPV frequently escalates during pregnancy and may result in serious consequences, including death to both the mother and the unborn child.35 Further, depression and suicidal ideation have been identified as common sequelae of IPV.32,36–38 Data also show that there are associations between IPV in the perinatal period and poor maternal health behaviors, such as greater use of ATOD, a lower likelihood of ceasing substance use during pregnancy, and delay in prenatal care.39–41 Substance abuse by women of childbearing age (8%–18% prevalence) is problematic because it poses hazards to women's health and reproductive health. Substance use during pregnancy is especially dangerous, as it directly impacts both mother and child, increasing prematurity, intrauterine or neonatal death, and child maltreatment.42–45 Depression is also common among substance-abusing caregivers and affects one's ability to parent.46,47 The overlapping incidence of depression, victimization, and substance use argues for linking these three psychosocial issues for screening. Further, as these problems occur throughout pregnancy, data argue for repeated screening throughout the perinatal period.6,13,40,48–50

With the awareness of maternal depression, IPV, and ATOD as prevalent public health issues and their important links to child health and maternal health, attention has turned to how healthcare providers can respond effectively.12,47,51–54 Screening protocols that healthcare providers can use to systematically assess women for depression and associated risk factors are endorsed by professional associations50,55,56 and have resulted in legislative mandates for perinatal screening,57–59 yet screening is not routinely done by either prenatal care providers or primary care providers treating young children.

Recognition and Treatment of Maternal Depression

Antenatal visits are an ideal venue to screen for and intervene with psychosocial issues, as the perinatal period is a high-risk time for the emergence of depressive symptoms and many women have their only contact with the healthcare system during pregnancy. Notably, almost 19%, or 1 in 5 women, experience maternal depression during the perinatal period,5 yet most are unlikely to receive effective treatment.9 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)50 recommends psychosocial screening of pregnant women at least once per trimester, but screening in routine care is uncommonly done.6,8,11,53,60

Although it is clear that screening programs are beneficial, the majority of programs screen for a single psychosocial issue (i.e., depression) rather than acknowledging the co-occurrence of a triad of psychosocial issues: depression, IPV, and ATOD. Reasons for the gap between recommendations for the implementation of screening in pregnant women and actual practice have been the subject of numerous commentaries. Goldman et al.61 identified the barriers to successful recognition and treatment as stigma, patient denial, limited provider skills and time, differences in the healthcare delivery system, restrictive insurance coverage, and lack of mental health providers. LaRocco-Cockburn et al.11 found that many obstetrician/gynecologists believe they have a responsibility to identify depression, but they are not usually provided with the appropriate resources and training to screen for and treat depression. Studies to address such barriers have shown successful depression care requires a systematic approach to detection and linkages to treatment.49,51,62–67

Assessment models

Recently, four models for depression screening have been presented in the literature. Gordon et al.63 developed a department-based perinatal depression screening program in an academic medical center located in a large Midwestern city. The comprehensive program included (1) a network of community mental health providers to accommodate screen positive referrals, (2) a 24/7 hotline staffed by mental health workers to respond to urgent/emergent patient needs, (3) provider (nurse and physician) education via a comprehensive curriculum, and (4) outpatient depression screening (English and Spanish versions) that included a centralized scoring and referral system. Results indicated that screening was feasible when individualized physician practices were not required to develop the infrastructure necessary to respond; rather, the program's provision of clinical safety nets (mental health provider network and the hotline) were key to the program's success. However, antepartum screening was not completed by many patients because of late transfer of care to the department, no prenatal care at all, and variable provider compliance with the screening recommendation.66

The Partnership for Women's Health (PWH) of Baker-Ericzén et al.62 was designed to facilitate providers' ability to interact with patients and to link patients with services as a direct result of appropriate and timely identification of maternal depression. Based on the Partnership for Smoke Free Families (PSF),68 PWH follows the guideline of the 4 A's: Assess, Advise, Assist, and Arrange Follow-up and outsourcing components of the intervention to a licensed mental health professional to provide further intervention and referral services to the women by phone. Results indicated that the program was feasible in both obstetric and pediatric offices and that providers reported an increased ability to identify and address maternal depression.62 Mothers reported that the screening instrument was easy to complete and, overall, were happy to discuss their symptoms with their obstetrician or baby's pediatrician. Mothers highly endorsed the proactive contact by the mental health advisor (MHA), who helped them to understand their condition and feel more comfortable in seeking services.62 Although the PWH was successful, the study population was primarily Caucasian and affluent.

The Perinatal Depression Management Program (PDMP) developed by Miller et al.67 is a perinatal care setting diagnostic assessment and treatment model for primarily Spanish-speaking Mexican women who screen positive for depressive symptoms. Preliminary findings indicated that PDMP could incorporate formal maternal depression diagnosis assessment by (1) training providers, (2) streamlining the assessment process, (3) providing a user friendly assessment tool, (4) incorporating the screen into clinic flow, and (5) creating easy documentation via a checklist at the end of the assessment tool. The model was feasible and initially well accepted; however, a marked decline in the third month of the program indicated a need for periodic reminders and in-services.67

Katz et al.64 designed a city-wide primary care research study in collaboration with six academic institutions in Washington, DC, to improve pregnancy outcomes for low-income African American pregnant women. Healthy Outcomes of Pregnancy Education (DC HOPE) is a multiple risk factor clinical intervention trial targeting four known risk factors associated with preterm delivery, low birth weight, and infant mortality. These four factors are (1) maternal cigarette smoking, (2) environmental tobacco smoke exposure, (3) depression, and (4) IPV. Mothers are screened at a prenatal clinic visit to assess their eligibility and risk status by completing a brief self-administered computerized screening battery. Respondents listen to recorded questions through a headphone and then choose a touch screen response option to identify risk for smoking, depression, or IPV. The intervention is designed to target one or all of the risk factors and is scheduled concurrently with perinatal care visits to reduce time burden and maximize participation. The program is delivered over 10 weekly sessions by trained pregnancy advisors with advanced degrees in counseling discipline. Manualized protocols for the delivery and content of each risk factor and intervention session using Cognitive Behavioral Therapy approaches is used. Study findings demonstrate the feasibility of incorporating a computerized screening procedure for low-income African American women. The computer-assisted screening technique was well accepted by the study participants; it provided a sense of confidentiality, minimized administrative time for clinical personal, and identified the risks in a substantial portion of the population screened.64

In summary, across these four models, a number of features are important. A collaborative care approach with mental health specialists69 improves identification, outcomes, and the cost-effectiveness of care.70 However, Lusskin et al.49 indicate that the ideal screening method and timing in routine perinatal care have yet to be identified. Additionally, these models were not specifically developed to support screening/referral partnerships necessary for long-term sustainability within community obstetric health settings. Notably, the various models in the literature have some similar key components, including using feasible screening tools, incorporating mental health professionals, and training healthcare professionals. Yet no existing model is comprehensive with regard to incorporating all these features, and no current approach is based on a collaborative community care conceptual model. Thus, this article presents The Perinatal Mental Health Model, a community-based model that developed screening referral partnerships for use in community obstetric settings in order to specifically address the multiple psychosocial needs (depression, smoking, substances, and IPV) of culturally diverse, low-income mothers.

Conceptual Basis for the Perinatal Mental Health Model

Collaborative care is a systematic approach that includes (1) a negotiated definition of the clinical problem in terms both the patient and healthcare provider understand, (2) joint development of a care plan, (3) provision of support, and (4) active sustained follow-up.71,72 In collaboratives, multiple organizations work together on a specific problem, guided by evidence-based change principles. Although collaborative models have appealing face validity, there are few controlled studies of their effectiveness,73 and the sparse data have produced varying results.74–76 In addition, although there is general agreement that collaborative care delivers better outcomes, treatment is more expensive than in traditional care.51,74

One specific collaborative model, the Chronic Care Model (CCM),77 has been implemented for a variety of health conditions, including depression.78 Within the CCM, the health organization integrates diverse elements that cultivate prepared physicians, practice teams, and informed patients. These elements include (1) self-management support, (2) delivery system design, (3) decision support, and (4) clinical information systems. Potential obstacles to implementing the CCM include high costs for clinical information systems, limited physician time per patient, and physician misconceptions.79,80 Wells et al. developed the multisite Partners in Care (PIC) quality improvement intervention based on CCM principles for depressive disorders in primary care. In the PIC study, Wells et al.81,82 determined that interventions improved clinical outcomes more for minorities than for whites. In the 5-year follow-up, Wells et al.83 found significant but modest clinical improvements for the whole sample and significantly greater clinical improvement and quality of life for minorities compared with whites. The CCM is widely recognized to improve chronic medical conditions and has features that make it appealing for integrating screening/assessment protocols into routine practice in obstetrics/gynecology settings. Efficient approaches for this integration, however, have not been well developed.

Another collaborative model, PSF, addresses system and patient barriers by establishing a program for timely identification of a targeted condition and outsourcing patient support.68,84 The PSF model follows the recommended guideline of 5 A's: Ask, Assess, Advise, Assist, and Arrange follow-up (expanded from the original 4 A's model). It outsources three of the components (Advise, Assist, and Arrange follow-up) to minimize clinic burden while increasing the attention and assistance to patients. The outsourced health advisor provides proactive support to patients, addressing barriers of stigma, denial, limited knowledge, inaccurate beliefs, restricted insurance coverage, and challenges in navigating the system, and links them with services. The PSF program proved to be highly successful, screening over 100,000 perinatal women and linking over 15,000 to services in San Diego. Results showed that when given a toll-free number, only 3% of the women accessed services from a resource guide; 97% required a proactive contact to access and receive services.84 The program has been disseminated across San Diego county, screening over 170,000 women and linking 35,000 to services, with 611 providers participating to date because of its low cost, low burden procedures. Additionally, 5,000 women received all cessation treatment by phone, and program results showed these women were 17 times more likely to receive cessation services.84

The Perinatal Mental Health Model (PMH) is an extension and elaboration of our earlier PWH Model (see ref. 62 for a comprehensive program description). The PMH program was developed in collaboration with community-based maternal/child health providers and consumers. Building on the earlier work of the Depression in Women Advisory team,62 the team was reconstituted to include members with expertise in IPV, ATOD, child developmental outcomes, and maternal depression. This multidisciplinary team included healthcare providers (midwives, obstetricians, nurses), psychologists, sociologists, program managers, researchers, and bicultural low-income consumers. The inclusion of low-income ethnically diverse consumers on the advisory group provided the opportunity to gain culturally relevant responses to the intervention and generated enthusiasm for the project. Members represented institutions across San Diego County, including San Diego County Health and Human Services, Department of Public Health, University of San Diego, University of California San Diego, and the Child and Adolescent Services Research Center (CASRC). This advisory team indentified (1) appropriate screening tools for IPV, ATOD, and maternal depression, (2) existing community resources, and (3) assistance in problem-solving health system-related issues.

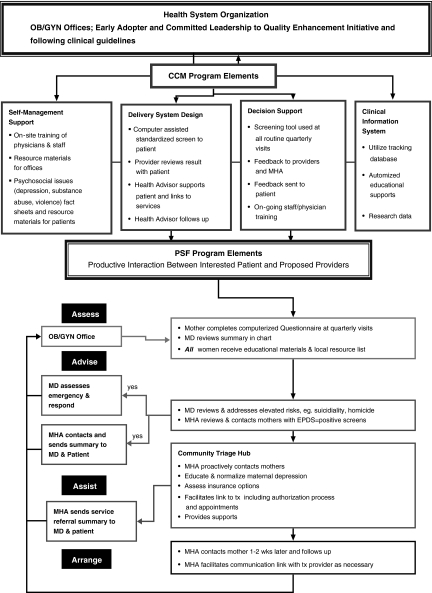

The PMH model integrates elements of both the CCM77,78 and PSF68 (Fig. 1). In combination, the two models offer conceptual (CCM) and pragmatic (PSF) plans to increase the ability of community maternal/child health care providers to increase the use of (1) clinical guidelines and (2) evidence-based practices and (3) to productively interact with patients through a collaborative partnership with mental health systems and community programs. The PMH intervention includes transforming health system organizations by developing the CCM system elements: (1) self-management support, (2) delivery system design, (3) decision support, and (4) clinical information system and incorporating the original PSF 4 A's: (1) Assess: systematically identify maternal psychosocial issues at regular visits using standardized screening measures, and (2) use a centralized MHA to proactively contact at-risk mothers to Advise, Assist, and Arrange follow-up. These specific strategies facilitate implementing the delivery system changes and decision support elements in a manageable and cost-efficient manner while minimizing the burden to the organization and healthcare providers. PMH addresses the specific barriers of limited provider skills, minimal time, and organizational costs while supporting the adoption of the CCM elements by multiple community healthcare organizations without intensive changes to the organization (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

The Perinatal Mental Health Model. CCM, Chronic Care Model; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; MHA, Mental Health Advisor; OB/GYN, obstetrics/gynecology; PSF, Partnership for Smoke Free Families.

Assess: Screening for psychosocial issues

Standardized screening tools in a technology-supported assessment battery are used for the screening of psychosocial issues, including depression, IPV, substance use, and smoking (including environmental exposure) during perinatal and 6-week postpartum visits. The battery includes the following screens: (1) Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)85 for maternal depression, (2) the Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS)86 for IPV, (3) TWEAK87 for alcohol use, (4) the Short Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10)88 for drug use, and (5) the PSF Health Survey for New Moms-Tobacco Use Questionnaire68 for smoking patterns and environmental exposure. The screens (English or Spanish versions) are completed on a laptop computer with the assistance of a bilingual facilitator while the mother is in the waiting room before seeing the healthcare provider. At the time the screen is administered, all women receive an educational handout on maternal psychosocial issues, and those with a positive screen also receive a list of local resources.

Measures

The EPDS85 is a 10-item self-report scale specifically designed to assess depressive symptoms. EPDS removes items related to physical symptoms of depression that may be affected by the perinatal period rather than by mood. It is not a diagnostic tool but a screening tool that asks about depressive symptoms in the past 7 days. Scores range from 0 to 30, with a higher score representing depressive symptomatology. Cutoff scores range from 9 to 13. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends “to err on safety's side, a woman scoring 9 or more, or indicating any suicidal ideation (scores 1 or more on item 10), should be referred immediately for follow-up. Even if the woman scores less than 9, if the clinician feels the woman is suffering from depression, an appropriate referral should be initiated.”89 The EPDS has been extensively used and validated across multiple community, cultural, and ethnically diverse populations,85,90–92 has validated English and Spanish versions,13,93 and has been used to identify the prevalence in pregnant13,94 and postpartum Latinas living in the United States.24,95

The AAS,86 a 4-question screen that has been used to identity abused women in prenatal and other healthcare setting, is used to screen for IPV. The AAS is recommended by the March of Dimes for assessment of abuse with all pregnant women96 and has strong support for reliability and construct validity with the Conflict Tactics Scales and other measures of IPV.86 The screen is prefaced by the statement: “Since domestic violence is so common in women's lives and has serious effects on women's and baby's health, we are asking all women the following questions about abuse. This protocol eliminates the potential interpretation that the woman is being singled out for some reason and the assertion of the widespread nature of abuse helps to decrease any stigma attached to the topic.”86

TWEAK87 is a 5-item scale developed to screen for high-risk drinking during pregnancy. It is one of the few alcohol screening tests developed and validated among women. The utility of items in the TWEAK was demonstrated in studies of obstetric and gynecological outpatients.87,97,98

The DAST-1088 is a 10-item version of the original DAST designed to identify drug use-related problems in the previous year. The DAST-10 is internally consistent (alpha = 0.86) and temporally stable (interclass correlation coefficient = 0.71). PSF Health Survey for New Moms-Tobacco Use Questionnaire68 is used to screen for smoking risk during the perinatal period.

Assessments are scored immediately through a computerized scoring algorithm, and a summary of results is printed, with a copy for the provider and the patient. The patient's copy prompts her to speak to her provider about her condition if screened positive for maternal depression (MD) (≥10), IPV, ATOD, or smoking. The provider's copy prompts the provider to conduct follow-up assessment for situations that require immediate attention, such as EPDS ≥10 or endorsed item 10, suicidal ideation or homicide, child abuse, and DAST-10 ≥6. All original assessment data are maintained in the woman's health chart or entered into her electronic medical record.

Provider and staff training includes written and verbal instructions about the implementation of standardized screening, use of the measures, standardized cutoffs, guidelines for referrals, a protocol for assessing suicide (ideation, intent, and the existence of a plan), and a direct referral line to the adult emergency screening unit in their area for an urgent mental health referral. Providers are also provided scripts to inform the patient that an MHA will be contacting them by phone to facilitate a link to treatment resources and provide additional supports.

Advise, assist, and arrange follow-up: Linking mothers to treatments

A key component of the PMH program model is to proactively contact mothers who screen positive and link them with existing appropriate treatment resources. These components are outsourced to the centralized MHA in order to maximize resources and minimize the burden to busy offices. MHAs are from a variety of behavioral health trained disciplines, including Licensed Clinical Social Work, Marriage and Family Therapy, Mental Health Advance Practice Nurses, and Clinical Psychology. The MHA is informed via confidentiality protected e-mail and phone call of all positive screens.

The MHAs are trained to (1) actively engage the mothers, (2) intervene by reviewing the depression scores and significant risk factors, such as suicidal ideation, homicidality, child abuse, IPV, ATOD, and smoking, and (3) provide extensive assistance to the mother in addressing her depression and accessing appropriate services. More specifically, the MHAs are trained in assessment, intervention, and treatment of each of the psychosocial issues named above in the perinatal period and to proactively contact positively screened mothers to: Advise, Assist, and Arrange follow-up within 24–48 hours by telephone. Telephone support services have been found to be an effective method of intervention99–101 and are used to reduce the economic burden on patients, transportation problems, and child care concerns and to increase receipt of supportive services.

In order to reduce false positives and to further assess psychosocial issues, the MHA reviews symptomotology and clinical issues with the mother, including depression, anxiety, violence, and substance use, and administers the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) structured clinical interview by telephone.102 Information is also collected from the mother about her support systems, current strategies for caring for herself, insurance coverage, and attitudes and beliefs about receiving medical and mental healthcare.

Next, the MHA educates the mothers on maternal depression (as well as co-occurring conditions), provides support, assists to destigmatize the condition by normalizing it (providing prevalence figures and role models who have experienced it), and provides a physical explanation of the condition.103 The MHAs provide direct assistance to the mothers to address the depression and other conditions through the following interventions: encourages mothers to obtain support from others, provides information on evidence-based intervention options (medication, psychotherapy, exercise), provides short-term cognitive-behavioral intervention strategies (i.e., increasing participating in pleasant activities, using cognitive restructuring), provides direct links to existing appropriate treatment resources based on their insurance status and treatment preferences (scheduling appointments for them when indicated), assists with navigating the healthcare system (explaining types of services and providers), follows up to facilitate/assess access to treatment (addressing barriers to service receipt), assumes the role of communication/system navigation bridge, and provides patient-specific feedback to the healthcare provider (HCP).

After the initial contact, the MHA sends a patient contact report to the HCP (1) summarizing the treatment, education, and resources that were given to the mother (2) to maintain the HCP's involvement in the patient's care, and (3) to assist the HCP in providing appropriate advice or starting medication treatment as necessary. At two follow-up points (1–2 weeks and 4–5 weeks) after the initial contact with each mother, the MHA conducts a follow-up phone call to determine if the mother has accessed any resources, has had difficulty accessing resources, or is experiencing any new or ongoing symptoms requiring additional resource links. Again, the mother is provided intervention strategies and support to access services. The MHA positively reinforces mothers who have accessed services or followed the recommended behavior changes (i.e., exercise, activities, supports) to address symptoms.

Implementation

The PMH team tailored the PMH model to be culturally and linguistically appropriate for screening and addressing maternal depression, IPV, and ATOD during the perinatal period. Specifically, given that the majority of Spanish-speaking populations in Southern California are of Mexican descent or immigrants from Mexico, two bilingual, bicultural Mexican Americans (one psychology student and one public health student) translated the screening battery and educational handout into Spanish. Reverse translation was next conducted by two different individuals (one M.S.W. and one family counselor). Key informant interviews soliciting feedback on the proposed model from MCH providers and multicultural consumers, as well as a pilot examining program acceptability and feasibility with low-income women, were conducted. All study procedures, including protocols for recruiting participants and obtaining written informed consent, were reviewed and approved by appropriate institutional review boards and administrators.

First, a focus group with 12 pregnant Spanish-speaking Latinas was conducted to explore the acceptability of answering questions about maternal depression, including its relationship to maternal and child health. The principal investigator (PI) and two bilingual/bicultural research assistants led the focus group using a transcripted interview guide that included open-ended questions to learn about the participants' (1) understanding of the EPDS and (2) experiences with maternal depression. The focus group was tape recorded and transcribed for analysis using a method of Coding, Consensus, Co-occurrence, and Comparison outlined by Willms et al.104 Recurrent themes that emerged included (1) motherhood is a time of joy and (2) difficulty in talking with family. The mothers ranged in age from 16 to 39 years (mean = 29.8, standard deviation [SD] = 7.63) and were receiving services from and recruited at the Central Region Public Health Center. Participants completed the Spanish version of the EPDS and then were asked: Did the items have any meaning? Were the words in the questions commonly used in discussion with family, friends, and the community where you live? How could the questions be improved? They were also asked to talk about maternal depression, their perspective on screening for maternal depression, as well as personal experiences and feelings related to maternal depression during their current or previous pregnancy and the year after childbirth if they had previously given birth. All scored ≥10 (EPDS), 4 scored 10–13, and 8 scored ≥14 (range 12–20; mean = 16.6, SD = 2.7). Questions on the EPDS had meaning to them. Two of the participants reported they had experienced depressive feelings after the birth of a child but had difficulty in talking with their families or friends. “Motherhood is supposed to be a time of joy, but I just would cry and cry and cry.” They also pointed out that depression is very limited in their community; “pregnancy is a happy time, greatly looked forward to, probably affects more women who don't have a partner or close family connections.” Women also talked about the stigma associated with mental health issues and involvement with mental healthcare. However, they stated they were comfortable completing the screening tool and that talking about it would help women identify and address their problems. Notably, participants endorsed that they were comfortable talking about mental health issues with the research assistant as well as their healthcare providers. They also thought that having someone to help them access services would be very helpful as they did not want to burden their providers.

Next, a feasibility study was conducted to determine if pregnant, low-income, ethnically diverse women would be receptive to PMH and could be recruited through the protocol that was used in the first PWH pilot study described by Baker-Ericzén et al.62 Of 55 women approached about the study at two community clinics, 50 (90%) were willing to complete our screening, knowing that they might be contacted via phone at a later date. Reasons mothers gave for not participating included living outside of the country (Mexico), lack of telephone access, and “don't have the time.” Approximately 88% of the sample were Latina, 6% white, and 6% other race/ethnicity. Mothers' ages ranged from 18 to 44 (mean = 25.2, SD = 5.76). All the mothers were from low-income households and were accessing care along the continuum from the first through the third trimester.

A bilingual, bicultural research assistant (1) administered the survey comprising demographic items and the standardized measures: EPDS, AAS, TWEAK, DAST-10, PSF Tobacco use items and (2) asked participants open-ended interview questions about maternal depression, including its relationship to maternal and child health, family conflict resolution strategies, substance use, and the appropriateness of the screening measures. Questions included: Did you understand the EPDS, AAS, DAST-10, TWEAK, tobacco use items? Did you have experiences with any of the psychosocial issues?

EPDS scores ranged from 0 to 17 (mean = 3.85, SD = 4.14). Seven women (14%) scored positive for maternal depression (score ≥9), and of those, 4 scored ≥10 (of these 4 women, 2 had scores between 10 and 13, and 2 had scores ≥14). Approximately one third scored ≥1 on the TWEAK, and scores ranged from 1 to 7 (mean = 4.25, SD = 1.77); 28% scored ≥3, indicating risk for harmful drinking. DAST scores ranged from 0 to 3. Sixty-eight percent (n = 39) reported no drug use; 18% (n = 9) scored in the low level (1–2), and 2 scored in the moderate level (3–4) for degree of problems related to drug abuse. Only 2 reported smoking at the time of the interview.

Of the 7 women who screened positive for depression, the MHA reached 5 by phone and administered a structured clinical interview. Of these 5 women, 2 met criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD) (EPDS = 11 and 17), 1 met criteria for current minor depressive disorder, and 2 women did not meet criteria for a mood or substance use disorder (EPDS = 9 and 9). In addition, 1 woman who screened positive for substance use but not maternal depression (EPDS = 8, TWEAK = 2, DAST = 2) met criteria for a history of alcohol and substance dependence. Those who met criteria for a diagnosis received psychosocial education on that diagnosis, specific behavioral strategies to implement (i.e., behavioral activation), discussion of treatment options (medication, therapy, and support groups), and direct linkage to services as desired and indicated (assistance in making a treatment appointment). Mothers reported the questions were clear and items were meaningful. In addition, they were receptive to the MHA treatment recommendations and links to resources, with 100% reporting high satisfaction with MHA contact.

Conclusions

Maternal depression is the leading cause of disease burden worldwide, and mothering young children increases the risk of depression. IPV and ATOD are important factors related to depression, and the extent of the overlapping incidence warrants linking these three elements along with smoking behaviors in assessment. Notably, this is an important target for prevention efforts, and the obstetric healthcare sector is a primary gateway to care for low-income pregnant women. Thus, it is important to develop sustainable models for identification and treatment of maternal depression and co-occurring psychosocial issues in this sector.105 PMH was designed to address the multiple needs of low-income women in community obstetric settings.

Implementation evolved using a process that led sequentially from convening the advisory group to a focus group study of the understanding of maternal depression and, finally, to a pilot feasibility study of PMH in a sample of low-income, ethnically diverse pregnant women. The inclusion of consumer perspectives and those of other advisory group members helped develop enthusiasm for the project. Key informant interviews provided insight into the many intricacies of the Latino culture, including high rates of poverty, immigration status, acculturation, discrimination, conflict resolution strategies, role of religion, spirituality, values related to family, childbearing, motherhood, mental health illness, and seeking mental health services. Our pilot work revealed that mothers are responsive to the approach built into PMH and welcomed the screening and discussion of maternal depression/other psychosocial issues with their providers. They also appreciated the proactive contacts from the MHA. Based on our pilot data, the Mental Health Advisor title was changed to Maternal Health Advisor to address Latino attitudes toward mental illness and to decrease the stigma associated with accessing mental health services. Ongoing qualitative methods will continue to facilitate the assessment of sociocultural influences while making program adaptations as needed, based on the derived qualitative data and patient preferences.

Potential program limitations include implementation challenges, attrition, and cost-effectiveness. The greatest implementation challenge is gaining access to the community clinics. Although there is great enthusiasm among clinical and administrator colleagues for the program, real world barriers include clinical space considerations, perceived staff burden, assumed duplication of screening, and concern for lack of appropriate referral and follow-up services. The most successful approach to overcoming these barriers has been partnering with one or more committed healthcare providers in a setting to demonstrate the seamless screening with real time report generation for both the woman and her healthcare provider at the time of the visit and the feedback from the MHA to the woman and her provider.

The feasibility study was limited to short-term contact with participants and does not demonstrate that women will be retained through the duration of the program. Based on our past work, however, we anticipate a 15% attrition rate by program completion. Notably, Healthy Families San Diego106 recruited 488 (85% retention over 3 years) low-income, ethnically diverse postpartum women to participate in a randomized clinical trial of home visitation services. In-home and telephone interviews were conducted that included sensitive topics, such as depression, violence, and substance use. Retention strategies included (1) current participant contact information and the contact information of three individuals likely to know their locations over time as well as any plans to relocate; this information was collected at each data collection point, (2) well-organized tracking databases and frequent respectful contact with the mothers; for example, holiday cards and infant development milestone materials are sent to maintain mother's connection with program, (3) financial compensation at each data collection, (4) scheduling interviews at the participants' convenience (evenings, weekends), (5) phone interviews to reduce participant burden, and (6) to the extent possible, the same staff person will complete all assessments so that women have a personal contact with the study.

PMH includes cost-efficient and time-efficient procedures, including technology-assisted screening and an MHA to support providers and proactively contact depressed mothers, engaging them and linking them to appropriate treatment resources. Cost-effectiveness analysis will be conducted after the intervention trial is completed, although the costs of the pilot program have been estimated. Because of the cost-efficiency of delivering the MHA services over the telephone (no travel time, no wasted time on no show or late appointments), we estimate that the cost for the women participating in the pilot study averaged $161 per woman served, with each woman receiving a minimum of two contacts. The MHAs work 10 hours per week and average eight telephone contacts per week, and the range of the contact time is 10 minutes for a follow-up call to 90 minutes for an initial call.

In summary, three key innovative features of the PMH program are (1) a culturally sensitive intervention to reduce culturally mediated, psychological, social, and environmental barriers to care for depression and the related problems of ATOD and IPV, (2) specific treatment continuation and maintenance intervention elements to integrate care for psychological issues within primary care,107 and (3) use of MHAs to link clinical and systems strategies, such as supporting providers and patients to navigate community services, in order to reduce fragmented supportive services in public sector systems. Despite the acknowledged limitations, PWH has the potential to be an effective approach to address these damaging conditions, with lifelong implications for both mother and child.23

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Mentored Research Scientist Development Award K01-DA15145 (C.D.C) and the National Institute of Mental Health Mentored Research Scientist Development Award K01-MH65454 (A.L.H.).

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. A message from the Director General. 2001. www.who.int/whr/2001/dg_message/en/index.html. [Aug 2;2009 ]. www.who.int/whr/2001/dg_message/en/index.html

- 2.Murray CJL. Lopez AD. The global burden of disease: A comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett HA. Einarson A. Taddio A. Koren G. Einarson TR. Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: Systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:698–709. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000116689.75396.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dietz P. Williams S. Callaghan W, et al. Clinically identified maternal depression before, during, and after pregnancies ending in live births. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1515–1520. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaynes BN. Gavin N. Meltzer-Brody S, et al. Perinatal depression: Prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment. 2005;119:36. doi: 10.1037/e439372005-001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horwitz SM. Bell J. Grusky R. The failure of community settings for the identification and treatment of depression in women with young children. Community based mental health services for children and adolescents with mental health needs: Research in community and mental health. 2007;14:13–31. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lanzi RG. Pascoe JM. Keltner B. Ramey SL. Correlates of maternal depressive symptoms in a national Head Start program sample. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:801–807. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.8.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connelly CD. Baker MJ. Hazen AL. Mueggenborg MG. Pediatric health care providers' self-reported practices in recognizing and treating maternal depression. Pediatr Nurs. 2007;33:165–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flynn HA. O'Mahen HA. Massey L. Marcus S. The impact of a brief obstetrics clinic-based intervention on treatment use for perinatal depression. J Womens Health. 2006;15:1195–1204. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heneghan AM. Silver EJ. Bauman LJ. Stein RE. Do pediatricians recognize mothers with depressive symptoms? Pediatrics. 2000;106:1367–1373. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.6.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LaRocco-Cockburn A. Melville J. Bell M. Katon W. Depression screening attitudes and practices among obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:892–898. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horwitz SM. Briggs-Gowan MJ. Storfer-Isser A. Carter AS. Prevalence, correlates, and persistence of maternal depression. J Womens Health. 2007;16:678–691. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yonkers KA. Ramin SM. Rush AJ, et al. Onset and persistence of postpartum depression in an inner-city maternal health clinic system. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1856–1863. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horwitz SM. Briggs-Gowan MJ. Storfer-Isser A. Carter AS. Persistence of maternal depressive symptoms throughout the early years of childhood. J Womens Health. 2009;18:637–645. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Judd LL. Akiskal HS. Maser JD, et al. A prospective 12-year study of subsyndromal and syndromal depressive symptoms in unipolar major depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:694–700. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.8.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lovejoy MC. Graczyk PA. O'Hare E. Mewman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analystic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2000;20:561–592. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.NICHD Early Childcare Research Network. Chronicity of maternal depressive symptoms, maternal sensitivity and child functioning at 36 months. Dev Psychol. 1999;35:1297–1310. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.5.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weissman MM. Pilowsky DJ. Wickramaratore PJ, et al. Remissions in maternal depression and child psycho[athology. JAMA. 2006;295:1389–1398. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLennan JD. Offord DR. Should postpartum depression be targeted to improve child mental health? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:28–35. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reid AJ. Biringer A. Carroll JD, et al. Using the ALPHA form in practice to assess antenatal psychosocial health. Can Med Assoc J. 1998;159:677–684. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wells K. Sturm R. Sherbourne C. Meredith L. Caring for depression. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wisner KL. Zarin DA. Holmboe ES, et al. Risk-benefit decision making for treatment of depression during pregnancy. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1933–1940. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knitzer J. Theberg S. Johnson K. Reducing maternal depression and its impact on young children: Toward a responsive early childhood policy framework. NewYork, NY: National Center for Children in Poverty, Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health; Jan, 2008. Project Thrive Issue Brief No 2. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diaz MA. Le HN. Cooper BA. Munoz RF. Interpersonal factors and perinatal depressive symptomatology in a low-income Latina sample. Cult Diversity Ethnic Minority Psychol. 2007;13:328–336. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le H. Munoz R. Soto J. Delucchi K. Ippen C. Identifying risk for onset of major depressive episodes in low-income Latinas during pregnancy and postpartum. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 2004;26:463–482. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miranda J. Chung JY. Green BL, et al. Treating depression in predominantly low income young minority women: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:57–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Munoz RF. Le HN. Ippem CG, et al. Prevention of postpartum depression in low-income women: Development of the Mamas y Bebes/Mothers and Babies Course. Cogn Behav Pract. 2007;14:70–88. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zayas L. Jankowski K. McKee M. Prenatal and postpartum depression among low income Dominican and Puerto Rican women. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 2003;25:370–385. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hobfall SE. Riotter C. Lavin J. Hulsizer MR. Cameron RP. Depression prevalence and incidence among inner-city pregnant and postpartum women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:445–453. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Issacs M. Maternal depression: The silent epidemic in poor communities. Baltimore, MD: Annie E. Casey Foundation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pascoe JM. Stolfi A. Ormond MB. Correlates of mothers' persistent depressive symptoms: A national study. J Pediatr Health Care. 2006;20:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plichtas SB. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences: Policy and practice implications. J Interpers Violence. 2004;19:1296–323. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McFarlane J. Parker B. Soeken K. Silva C. Reed S. Severity of abuse before and during pregnancy for African American, Hispanic, and Anglo women. J Nurse Midwifery. 1999;44:139–44. doi: 10.1016/s0091-2182(99)00030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saltzman LE. Johnson CH. Gilbert BC. Goodwin MM. Physical abuse around the time of pregnancy: An examination of prevalence and risk factors in 16 states. Maternal Child Health J. 2003;7:31–43. doi: 10.1023/a:1022589501039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharps PW. Koziol-McLain J. Campbell J. McFarlane J. Sachs C. Xu X. Health care providers' missed opportunities for preventing femicide. Prev Med. 2001;33:373–380. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell JC. Kub J. Belknap RA. Templin TN. Predictors of depression in battered women. Violence Women. 1997;3:271–293. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dienemann J. Boyle E. Baker D. Resnick W. Wiederhorn N. Campbell J. Intimate partner abuse among women diagnosed with depression. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2000;21:499–513. doi: 10.1080/01612840050044258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Golding JM. Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. J Fam Violence. 1999;14:99–132. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heru AM. Stuart GL. Rainey S. Eyre J. Recupero PR. Prevalence and severity of intimate partner violence and associations with family functioning and alcohol abuse in psychiatric inpatients with suicidal intent. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:23–29. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Homish GG. Cornelius JR. Richardson GA. Day NL. Antenatal risk factors associated with postpartum comorbid alcohol use and depressive symptomatology. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1242–1248. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000134217.43967.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Molitor F. Ruiz JD. Klausner JD. Mcfarland W. History of forced sex in association with drug use and sexual HIV risk behaviors, infection with STDs, and diagnostic medical care: Results from the Young Women Survey. J Interpers Violence. 2000;15:262–278. [Google Scholar]

- 42.CASA. Substance abuse and the American woman. New York: Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, Columbia University; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neggers Y. Goldenberg R. Cliver S. Hauth J. The relationship between psychological profile, health practices, and pregnancy outcomes. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85:277–285. doi: 10.1080/00016340600566121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Pregnancy and drug use trends. 2001. www.nida/gov/infofax/pregnancytrends.html www.nida/gov/infofax/pregnancytrends.html

- 45.Smith WB. Weisner C. Women and alcohol problems: A critical analysis of the literature and unanswered questions. Alcoholism Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:1320–1321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bayes J. Substance abuse and child abuse. Impact of addiction on the child. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1990;37:881–904. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)36941-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kelly R. Zatzick D. Anders T. The detection and treatment of psychiatric disorders and substance use among pregnant women cared for in obstetrics. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:213–219. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chaudron LH. Kitzman HJ. Szilagyi PG. Sidora-Arcoleo K. Anson E. Changes in maternal depressive symptoms across the postpartum year at well child care visits. Ambul Pediatr. 2006;6:221–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lusskin S. Pundiak T. Habib S. Perinatal depression: Hiding in plain sight. Can J Psychiatry. 2007;52:479–488. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Psychosocial risk factors: Perinatal screening and intervention. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee Opinion No. 343. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:469–477. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200608000-00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gilbody S. Trevor S. House A. Screening and case-finding instruments for depression: A meta-analysis. Can Med Assoc J. 2008;178:997–1003. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Herzig K. Danley D. Jackson R, et al. Seizing the 9-month moment: Addressing behavioral risks in prenatal patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kerker BD. Horwitz SM. Leventhal JM. Patients' characteristics and providers' attitudes: Predictors of screening pregnant women for illicit substance use. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28:209–223. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leaf PJ. Owens PL. Leventhal JM, et al. Pediatricians' training and identification and management of psychosocial problems. Clin Pediatr. 2004;43:355–365. doi: 10.1177/000992280404300407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine. Recommendations for preventative pediatric health care. Pediatrics. 2000;105:645–646. [Google Scholar]

- 56.American Academy of Nursing Expert Panel on Violence. Violence as a nursing priority: Policy implications. Nurs Outlook. 1993;41:83–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Healthy Start Initiative Grants. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. www.mchb.hrsa.gov www.mchb.hrsa.gov

- 58.New Jersey legislature. www.njleg.state.nj.us/2006/Bills/S0500/213_I1.HTM www.njleg.state.nj.us/2006/Bills/S0500/213_I1.HTM

- 59.U.S. Senate S.3529. Mom's opportunity to access help, education, research and support for postpartum depression act. Senate of the United States; 109th Congress, 2nd Session; Mendendez, Robert. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lieferman JA. Dauber SE. Heisler K. Paulson JF. Primary care physicians' beliefs and practices toward maternal depression. J Womens Health. 2008;17:1143–1150. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goldman LS. Nielsen NH. Champion HC. Awareness, diagnosis, and treatment of depression. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:569–580. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.03478.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baker-Ericzén MJ. Mueggenborg M. Hartigan P. Howard N. Wilke T. Partnership for Women's Health: A new age collaborative program for addressing maternal depression in the postpartum period. Fam Syst Health. 2008;26:30–43. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gordon TE. Cardone LA. Kim JJ, et al. Universal perinatal depression screening in an academic medical center. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:342–347. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000194080.18261.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Katz KS. Blake SM. Milligan RA, et al. The design, implementation and acceptability of an integrated intervention to address multiple behavior and psychosocial risk factors among pregnant African American women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2008;8:1–22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim JJ. La Porte LM. Adams MG. Gordon T. Kuendig J. Silver R. Obstetric care provider engagement in a perinatal depression screening program. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009;12:167–172. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim JJ. Gordon T. La Porte LM. Adams MG. Kuendig J. Silver R. The utility of maternal depression screening in the their trimester. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:509.e1–509.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miller L. Shade M. Vasireddy V. Beyond screening: Assessment of perinatal depression in a perinatal setting. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009;12:329–334. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fiore MC. Bailey WC. Cohen SJ, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence clinical practice guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rubenstein LV. Jackson-Triche M. Unutzer J, et al. Evidence-based care for depression in managed primary care practices. Health Aff. 1999;18:89–105. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.5.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sturm R. Wells KB. How can care for depression become more cost-effective? JAMA. 1995;273:51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Katon W. The Institute of Medicine “Chasm” report: Implications for depression collaborative care models. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25:222–229. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(03)00064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kilo CM. A framework for collaborative improvement: Lessons from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement's Breakthrough Series. Qual Managed Health Care. 1998;6:1–13. doi: 10.1097/00019514-199806040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cretin S. Shortell SM. Keeler EB. An evaluation of collaborative interventions to improve chronic illness care. Framework and study design. Eval Rev. 2004;28:28–51. doi: 10.1177/0193841X03256298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Christensen H. Griffths K. Gulliver A, et al. Models in the delivery of depression care: A systematic review of randomized and controlled intervention trials. BMC Fam Prac. 2008;9:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-9-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Flamm BL. Berwick DM. Kabcenell A. Reducing cesarean section rates safely: Lessons from a “breakthrough series” collaborative. Birth. 1998;25:117–124. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.1998.00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shortell SM. Bennett CL. Byck GR. Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement on clinical practice: What it will take to accelerate progress. Milbank Q. 1998;76:593–624. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wagner EH. Glasgow RE. Davis C, et al. Quality improvement in chronic illness care: A collaborative approach. Joint Commission J Qual Improv. 2001;27:63–80. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(01)27007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Johnson J. Cost-effectiveness of mental health services for persons with a dual diagnosis: A literature review and the CCMHCP. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2000;18:119–127. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bodenheimer T. Wagner EH. Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: The chronic care model, Part 2. JAMA. 2002;288:1909–1914. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Daniel DM. Norman J. Davis C, et al. A state-level application of the chronic illness breakthrough series: Results from two collaboratives on diabetes in Washington State. Joint Commission J Qual Patient Safety. 2004;30:69–79. doi: 10.1016/s1549-3741(04)30008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wells KB. Sherbourne C. Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283:212–220. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Miranda J. Schoenbaum M. Sherbourne C. Duan N. Wells K. Effects of primary care depression treatment on minority patients' clinical status and employment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:827–834. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wells K. Sherbourne C. Schoenbaum M, et al. Five-year impact of quality improvement for depression: Results of a group-level randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:378–386. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hartigan P. Howard N. Moder C. San Diego, CA: Smoke-Free Families National Dissemination Office; 2004. Implementation of pregnancy specific practice guidelines for smoking cessation: Partnership for Smoke-Free Families program. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cox JL. Holden JM. Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Soeken KL. McFarlane J. Parker B. Lominack MC. The Abuse Assessment Screen: A clinical instrument to measure frequency, severity, and perpetrator of abuse against women. In: Campbell JCE, editor. Empowering survivors of abuse: Health care for battered women and their children. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. pp. 195–203. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Russell M. Bigler A. Screening for alcohol-related problems in an outpatients obstetric gynecologic clinic. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979;134:4–12. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(79)90787-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addict Behav. 1982;7:363–371. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.American Academy of Pediatrics. EPDS scoring. www.aap.org/sections/scan/practicingsafety/Toolkit_Resources/Module2/EPDS.pdf. [Jan 21;2007 ]. www.aap.org/sections/scan/practicingsafety/Toolkit_Resources/Module2/EPDS.pdf

- 90.Eberhard-Gran M. Eskild A. Tambs K. Opjordsmoen S. Samuelsen SO. Review of validation studies of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;104:243–249. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zelkowitz P. Milet T. Screening for postpartum depression in a community sample. Can J Pschiatry. 1995;40:80–86. doi: 10.1177/070674379504000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Murray L. Carothers AD. The validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale on a community sample. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:288–290. doi: 10.1192/bjp.157.2.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Alvarado-Esquivel C. Sifuentes-Alvarez A. Salas-Martinez C. Martinez-Garcia S. Validation of the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale in a population of puerperal women in Mexico. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2006;2:33–37. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-2-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mosack V. Shore ER. Screening for depression among pregnant and postpartum women. J Community Health Nurs. 2006;23:37–47. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn2301_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Affonso D. De A. Horowotz J. Mayberry L. An international study exploring levels of postpartum depression symptomatology. J Psychosom Res. 2000;49:207–216. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00176-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.McFarlane J. Parker B. Abuse during pregnancy: A protocol for prevention and intervention. White Plains, NY: March of Dimes; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Russell M. Bigler A. Screening for alcohol-related problems in an outpatients obstetric-gynecologic clinic. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979;134:4–12. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(79)90787-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Russell M. Martier SS. Sokol RJ, et al. Screening for pregnancy risk-drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18:1156–1161. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hunkeler EM. Meresman JF. Hargreaves WA, et al. Efficacy of nurse telehealth care and peer support in augmenting treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:700–708. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.8.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Simon G. Von Korff M. Rutter C. Wagner E. Randomized trial of monitoring, feedback, and management of care by telephone to improve treatment of depression in primary care. BMJ. 2000;320:550–554. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tutty S. Simon G. Ludman E. Telephone counseling as an adjunct to antidepressant treatment in the primary care system. A pilot study. Effective Clin Pract. 2000;3:170–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sheehan DV. Lecrubier Y. Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Powell J. Clark A. Information in mental health: Qualitative study of mental health service users. Health Expectations. 2006;9:359–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Willms DG. Best AJ. Taylor DW, et al. A systematic approach for using qualitative methods in primary prevention research. Med Anthropol Q. 1992;4:391–409. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Department of Health Human Services. Breaking ground, breaking through: the strategic plan for mood disorder research of the National Institute of Mental Health. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Landsverk J. Carrilio T. Connelly C, et al. Healthy Families San Diego clinical trial: Technical report. San Diego, CA: Child and Adolescent Services Research Center and San Diego Children's Hospital and Health Center; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Glasglow RE. Hiss RG. Anderson RM, et al. Report of the health care delivery work group: Behavioral research related to the establishment of a chronic disease model for diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:124–130. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]