Abstract

Engagement in HIV care is increasingly recognized as a crucial step in maximizing individual patient outcomes. The recently updated HIV Medicine Association primary HIV care guidelines include a new recommendation highlighting the importance of extending adherence beyond antiretroviral medications to include adherence to clinical care. Beyond individual health, emphasis on a “test and treat” approach to HIV prevention highlights the public health importance of engagement in clinical care as an essential intermediary between the putative benefits of universal HIV testing (“test”) followed by ubiquitous antiretroviral treatment (“treat”). One challenge to administrators, researchers and clinicians who want to systematically evaluate HIV clinical engagement is deciding on how to measure retention in care. Measuring retention is complex as this process includes multiple clinic visits (repeated measures) occurring longitudinally over time. This article provides a synthesis of five commonly used measures of retention in HIV care, highlighting their methodological and conceptual strengths and limitations, and suggesting situations where certain measures may be preferred over others. The five measures are missed visits, appointment adherence, visit constancy, gaps in care, and the Human Resources and Services Administration HIV/AIDS Bureau (HRSA HAB) performance measure for retention in HIV care. As has been noted for antiretroviral medication adherence, there is no gold standard to measure retention in care, and consideration of the advantages and limitations of each measure, particularly in the context of the desired application, should guide selection of a retention measure.

Introduction

Access to care has long been recognized as a vital factor in promoting and sustaining health and as a contributor to health care disparities.1,2 This global construct has typically been studied through population-based samples and large administrative databases focusing upon broad questions related to having a usual source of care and dichotomous assessment of medical services receipt at specific clinical venues (e.g., primary care) over a specified historic time interval (e.g., within the past 12 months). Such studies of the domestic HIV epidemic have resulted in estimates that between one third to two thirds of persons with known HIV infection are not in regular outpatient care.3,4

The term engagement in care embodies the distinct but interrelated processes of linkage to care and retention in care. In distinction to the more global construct of access to care, engagement in care measures outpatient medical service utilization with more granularity and on a longitudinal basis. Delayed linkage and poor retention in outpatient HIV care have been associated with delayed receipt of antiretroviral medications, higher rates of viral load failure, and increased morbidity and mortality.5–17 Beyond the effects on individual health, engagement in HIV care has important consequences for the public health as it plays a pivotal role in HIV transmission and secondary HIV infections. Studies have demonstrated reduced risk transmission behavior among HIV-infected patients engaged in clinical care,18,19 and viral load suppression, which is achieved more commonly among those with better retention,6,9 also reduces risk of transmission.20–22

Retention in care is being recognized as a crucial step in maximizing patient outcomes. The updated HIV Medicine Association guidelines for primary care of HIV infection state that, “emphasis should be placed on the importance of adherence to care rather than focusing solely on adherence to medications.”23 Similarly, quality indicators from Human Resources and Services Administration HIV/AIDS Bureau (HRSA HAB), the National Quality Forum (www.qualityforum.org/Measures_List.aspx), and HIVQUAL (www.hivguidelines.org/) all include retention in HIV care as a marker of quality care. The recent emphasis on a “test and treat” approach to HIV prevention highlights the importance of engagement in care as an essential intermediary between the putative benefits of universal HIV testing (“test”) followed by ubiquitous antiretroviral treatment (“treat”). In a recent commentary, leadership from the National Institutes of Health recognized the success of a “test and treat” prevention strategy is contingent upon the use of scientifically proven “efficient and effective means of entering and retaining patients in care.”21

This growing and well-deserved recognition that engagement in care is vital in optimizing patient outcomes is a result of emerging research on the topic, and has sparked additional investigation. In contrast to adherence to HIV medications and the more global construct of access to care, there has been a relative paucity of research on engagement in outpatient HIV care. One challenge to researchers and clinicians who want to study engagement is deciding on how to measure retention in care. Measurement of linkage is relatively straightforward as this processes either occurs or does not following HIV diagnosis, thus allowing for dichotomous measurement. In contrast, measuring retention is more complex as this process includes multiple clinic visits (repeated measures) occurring longitudinally over time. Recent studies, the majority of which have been retrospective and observational in design, have used a number of differing approaches to measure retention in care.5–17 To date, there has not been a published summary of these measures to serve as a guide and provide a common nomenclature for HIV retention measures. A recent review of retention in care noted, “a clear framework for how patient retention is defined and how it should be measured remains outstanding.”24 Our goal is to provide a synopsis of five measures commonly used to study retention in outpatient HIV care, highlighting the advantages, limitations, and potential applications of each measure.

Methods

We reviewed the available published literature and summarized findings of the most commonly used measures to ascertain retention in outpatient HIV medical care. We selected articles using the identified measures of retention to provide example applications of each measure. In this article, we describe the calculation, advantages, and limitations of five commonly used measures of retention in HIV care.

Measures of retention in care

Before defining and describing the calculation of each retention measure, some basic principles regarding a standardized approach to determining qualifying medical visits for computational inclusion are proposed. First, because survival with HIV infection is so dependent on access to antiretroviral therapy (ART), “care” has typically been conceptualized as a scheduled visit with a health care provider (whether physician, advanced practice nurse, or physician's assistant) who can prescribe or manage ART. As a result, studies of engagement in care have focused on primary HIV care visits and excluded medical subspecialty appointments. Notably, although visits with ART prescribers are usually used to measure retention in HIV care, the vital importance of retention for those not on ART cannot be overstated.7,10,12 Studies have typically included only scheduled outpatient medical appointments while excluding sick call or urgent care visits. In addition, while visits with social services, pharmacists, and nursing personnel are integral to team-based HIV management, those providers cannot directly prescribe or manage therapy and cannot provide longitudinal care independently, so have not be included in these calculations. Finally, appointments for which a patient called in advance to cancel and/or reschedule should be excluded analytically, in contrast to “no show” visits that represent missed appointments with no prior notification to the clinic.25 Similarly, appointments cancelled by the clinic and/or provider should be excluded when calculating measures of retention.

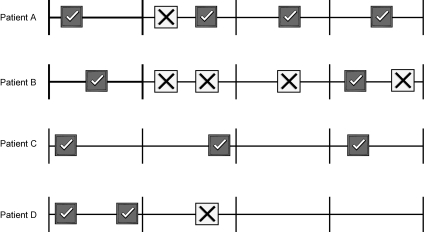

Some of these conventions have application across the five retention measures, whereas others are applicable only to a subset of measures, which is highlighted in the discussion of advantages and limitations. Ultimately, a clear description of the measures and methods employed are essential for studies of engagement in care, and the following section provides suggested nomenclature for the most commonly used measures of retention in care as a proposed common language as the field moves forward. We refer to clinic visit patterns of four fictitious patients during a 12-month observation period to demonstrate calculation of the five measures of retention in care (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Of note, in locations with mandatory reporting, HIV biomarkers (CD4 count and plasma HIV viral load) have been used to measure linkage and retention in HIV care, acting as a surrogate for a completed visit.26 While there are clear advantages to this approach from a public health perspective, a limitation is that biomarkers may be obtained in nonprimary HIV care settings (e.g., emergency department), thereby erroneously assigning some patients as retained in care.

FIG. 1.

Demonstration of calculation of retention measures using four hypothetical patients. Checked boxes indicate primary HIV care clinic visits attended by a patient, and boxes with an “X” indicate “no show” visits. The entire period is 12 months, with vertical marks dividing this into four 3-month periods. The accompanying Table 1 displays the 5 retention measures for the 4 hypothetical patients. The calculation of each measure is described in the methods section.

Table 1.

Retention Measures for Four Example Patients Calculated According to Clinic Visit Attendance during the 12-Month Observation Period

| Missed visits (dichotomous and count measure of “no show” visits) | Appointment adherence (number of completed visits divided by scheduled visits) | Visit constancy (number of 3-month periods with ≥1 completed visit) | Gap in care (6-month time period between completed visits) | HRSA HAB Performance Measure (≥2 completed visits during a 12-month period separated by ≥3 months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient A | Yes; 1 | 80% | 100% | No | Yes |

| Patient B | Yes; 4 | 33% | 50% | Yes | Yes |

| Patient C | No; 0 | 100% | 75% | No | Yes |

| Patient D | Yes; 1 | 67% | 25% | Yes | No |

HRSA HAB, Human Resources and Services Administration HIV/AIDS Bureau.

Missed visits

This measure captures the number of missed visits (“no show”) during an observation period of interest. The result is simply a count of missed visits, regardless of how many visits have been scheduled. This measure has been one of the most widely used retention measures in the literature and has been applied as both a dichotomous and as a count measure.5,10,11 We can see that patients A, B, and D have missed visits (1, 4, and 1, respectively), whereas patient C has no missed visits.

Appointment adherence

This measure is a proportion that captures the number of completed visits in the numerator and the number of total scheduled (completed plus “no show”) visits in the denominator during an observation period of interest.17 Studies have also modeled appointment non-adherence, sometimes referred to as the missed visit rate or proportion, by placing the number of missed visits (“no show”) in the numerator rather than the number of completed visits.8,9,16 Appointment adherence in patients A, B, C, and D is calculated as 80% (4/5), 33% (2/6), 100% (3/3), and 66% (2/3), respectively.

Visit constancy

This measure evaluates the proportion of time intervals with at least 1 completed clinic visit during an observation period of interest. We propose the term “visit constancy” for this measure, which heretofore has not had a distinct name. Typically, because treatment guidelines recommend laboratory assessments and visits for patients every 3–6 months, time intervals have ranged between 3 and 6 months.6,12,27 From the example in Fig. 1, a 12-month observation period is broken down into four 3-month time intervals. Patient A attended clinic visits in all four intervals and had 100% appointment constancy, whereas patients B, C, and D had completed visits in 2, 3, and 1 time interval, respectively, representing 50%, 75%, and 25% constancy. Of note, patient C had no missed visits during the 12-month observation period, but did not have a completed visit in the third interval.

Gaps in care

This measure calculates the time interval between completed clinic visits. The length of the time interval or whether the time interval exceeds a pre-determine threshold, typically ranging between 4 and 12 months, can be used as the measure.13–15 From the example in Figure 1, we see that patients B and D had a gap of over 6 months between completed visits, whereas patients A and C did not have a gap in care.

HRSA HAB medical visits performance measure

The HRSA HAB measure captures whether a patient had 2 or more completed clinic visits separated by 3 or more months in time during a 12-month observation period. The National Quality Center standards of HIV care includes a measure of 2 or more completed clinic visits separated by 60 days in time and occurring in two 6-month periods during a 12-month observation period. These are hybrid measures incorporating elements of appointment constancy and gaps in care. From Fig. 1 we see that patients A, B, and C all had 2 visits during the 12-month observation period that were separated by at least 3 months but patient D did not.

Discussion

A summary of advantages, limitations and application of the five measures of retention in care is presented in Table 2. The selection of a retention measure is based upon a number of factors including the purpose for measuring retention in care, the type of clinic visit data that are available, clinic scheduling practices, and computational issues. Clinicians providing clinical care and administrators and investigators conducting research will have different purposes for measuring retention, and hence some measures may suit their needs better than others.

Table 2.

Advantages, Limitations and Application of Commonly Used Measures of Retention in Care

| Measure | Advantages | Limitations | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Missed visits | Easy to measure | Dichotomous measure is crude | Preliminary research |

| Dichotomous and count applications possible | Does not incorporate a denominator or a variable number of scheduled visits | Short-term tracking | |

| Face validity | Handling cancelled visits analytically | Monitoring individual patient behavior for clinicians | |

| Widely used | Impact of automatic rescheduling on number of missed visits | ||

| Handling lost to follow-up | |||

| Appointment adherence | Easy to measure | Impact of variable number of visits in denominator | Research on exposure / response |

| More granular measure | Handling of cancelled visits analytically | Long-term tracking periods | |

| Face validity | Impact of automatic rescheduling on number of missed visits in the numerator | Panel of patients behavior for clinicians and administrators | |

| Similarity to ARV medication adherence measures | Handling lost to follow-up | ||

| Visit constancy | Face validity/treatment recommendations | Computationally more challenging | Research on exposure/response |

| Better accounts for loss to follow-up than missed visits or adherence measures | Appropriate length of visit interval may differ between patients based on disease severity (range, 3–6 months) | Long-term tracking period | |

| Only need to capture completed clinic visits to calculate | More granular than missed visits but less detail than appointment adherence | Particularly relevant for new patients establishing care and those starting ART | |

| Automatic rescheduling has no impact | |||

| Gaps in care | Easy to measure | Fairly crude, dichotomous measure | Link to research on out-of-care and reengagement |

| Surrogate for loss to follow-up | Appropriate length of gap (range, 4–12 months) | Administrative tracking | |

| Only need to capture completed clinic visits to calculate | Less amenable for use as a time-varying covariate | Monitoring individual patient behavior for clinicians | |

| Automatic rescheduling has no impact | Patients lost to follow-up will have an undefined gap | ||

| HRSA HAB Clinic Visit Performance Measure | Face validity/treatment ecommendations | Computationally more challenging | Administrative tracking and reporting |

| Overcomes limitation of appropriate interval length observed with constancy | Less granular than other appointment adherence and constancy | Clinic level quality assurance | |

| Only need to capture completed clinic visits to calculate | Local, regional and national planning for public health officials, managed care organizations, and third-party payers | ||

| Automatic rescheduling has no impact |

ARV, antiretroviral; ART, antiretroviral therapy; HRSA HAB, Human Resources and Services Administration HIV/AIDS Bureau.

In the following sections, salient features that may play a role in the selection of a retention measure are highlighted.

The clinician's perspective

For clinicians, the missed visits and gap in care measure are typically readily available at the point-of-care, and may serve as intuitive measures of retention. Many providers likely already review the medical record and note when the last visit was, or how many times the patient has missed visits recently. They then incorporate these measures in their routine patient care activities, for example, as a means to identify patients in need of case management or social work evaluation of potentially unmet needs (e.g., transportation, mental health services). Patient's patterns of missed visits are likely taken into account by providers in determining the time interval for a subsequent clinic visit, with shorter intervals used for those with more missed visits. Importantly, studies have shown the clinically relevant missed visit and gap measures of retention in care are associated with patient outcomes including clinical events and mortality.5,7,10–12,14,15

The administrator's perspective

Appointment adherence and the HRSA HAB clinic visit performance measures (as well as similar quality measures) may be preferable for administrators. Clinic-wide appointment adherence may allow for longitudinal tracking of retention in care and also for setting an overall clinic benchmark (e.g., >80%). It may also allow administrators to assess variability in appointment adherence between clinics, units within the clinics, or individual provider–patient panels. The HRSA HAB clinic visit performance measure may be used by clinic administrators to assess performance relative to recommended standards and the performance of other clinics, although a benchmark for this measure has not yet been determined by HRSA (http://hab.hrsa.gov/special/performance/measureMedVisits.htm). Furthermore, public health officials, managed care organizations and/or health care payers (e.g., HRSA, CMS) may use these measures to inform local, regional and/or national planning and resource allocation.

The researcher's perspective

The missed visits measure has been widely used for research and clearly has a role, particularly for preliminary research and short-term observation periods. However, appointment adherence and visit constancy may be preferable for research purposes, particularly for longer observation periods. These measures allow for more granular measurement of retention in care, facilitating assessment of exposure/response relationships between retention and outcomes. Notably, the missed visit and appointment adherence approaches have a limitation in patients who are lost to follow-up. These patients, who are clearly poorly retained in care, may be misclassified as engaged if they never had scheduled follow-up visits to miss. As a final research consideration, the missed visits, appointment adherence and visit constancy measures are all easily employed for use as a time-varying measure analytically, an advantage over the gaps in care and hybrid indicators, like the HRSA HAB measure, which are less amenable to use in this fashion.

In addition to the varying professional perspectives and considerations in utilizing retention in care measures, logistical issues are also germane to the selection of a retention measure. These issues are most relevant to administrators and researchers, although some have clear implications for clinicians as well.

Requisite clinic visit data

In contrast to the missed visits and appointment adherence measures, visit constancy, gaps in care, and the HRSA HAB clinic visit performance measure are calculated based on completed visits only. By not incorporating missed clinic visits in calculating these latter three measures, it is not necessary to differentiate which visits a patient failed to attend and did not notify the clinic (“no show”), from those that a patient called to cancel, and those cancelled by the clinic. These measures therefore require less complex data capture and manipulation.

As mentioned earlier, only “no show” visits have typically been included in the missed visit and appointment adherence measures.25 However, there clearly are issues related to the timing of cancelled visits worth noting. For example, a visit cancelled by a patient the week before the appointment is useful to the clinic because it is possible to use that slot for another patient. A visit cancelled 1 hour before a scheduled visit is less useful to the clinic. These issues are not a concern with the visit constancy, gaps in care and the HRSA HAB measures. However, not capturing missed visits in these latter measures also comes with a limitation. While they measure visit attendance at specified intervals serving as a marker of appropriate care, the impact of missed visits beyond these benchmarks of attendance is not taken into account.

Impact of clinic scheduling practices

Clinic scheduling practices must also be considered when selecting a retention measure. Clinics with automatic rescheduling of missed visits may lead to artificially poor missed visit and appointment adherence results, particularly if patient locator information is inaccurate and patients are not aware of rescheduled visits. From Fig. 1, this might have been the case for patient B who missed 3 consecutive clinic visits. However, clinic scheduling practices are not as much of an issue for the appointment constancy, gaps in care and HRSA HAB measure that are based only on completed visits. Accordingly, these measures may be particularly useful when comparing retention across settings in which variable scheduling practices are used.

Other issues related to clinic scheduling practices include how to handle walk-in or urgent care visits in retention measures, particularly when these visits occur with the primary provider but may focus on an acute medical problem rather than primary HIV care. Considerable variability exists among HIV clinics in the availability and approach to handling unscheduled or acute care visits. These local practices have implications for calculating and interpreting retention measures and need to be considered when choosing a measure. Finally, for open access approaches to clinic scheduling, the measures based upon completed visits only (constancy, gaps, and HRSA HAB performance measure) are likely most appropriate, as missed visits may not be as relevant and may be artificially decreased compared to traditional appointment scheduling practices.

Computational issues

The five measures present differing computational complexity. If data about both completed and missed visits are available, the missed visits and appointment adherence measures are the simplest to calculate, as the timing of visits is not necessarily a factor. In contrast, the visit constancy, gaps in care and HRSA HAB clinic visit performance measure that are calculated solely on completed visits require the timing of visits be taken into account.

The gaps and HRSA HAB measures are less computationally complex than the visit constancy measure, as the former two measures only require calculation of the time interval between completed visits. In contrast, measuring constancy requires the observation period of interest be divided into intervals of interest (e.g., 3–6 months) with subsequent determination of the number of intervals with a completed visit for each patient. An additional factor for consideration is whether time intervals are determined based on calendar time, and therefore using the same dates for all patients (e.g., January 1 to March 31, April 1 to June 30, etc.), or if each patient's interval dates are unique (although of the same duration) and linked to a common anchoring point across patients (e.g., date of ART initiation). This latter approach, although more desirable methodologically in many instances, presents more computational and programmatic complexity.

Sensitivity in capturing disease severity and stage of treatment

A final consideration in evaluating and selecting a measure of retention in care includes the sensitivity of each measure in capturing individual patient disease severity and stage of treatment. For example, more frequent medical visits may be indicated for patients newly establishing care, for those initiating or changing antiretroviral regimens, and for patients with more advanced HIV disease. The HRSA HAB performance measure is insensitive in capturing retention as it relates to issues of disease severity and stage, and rather represents a minimum standard of retention in care. Similarly, the gaps measure does not effectively account for disease severity. In contrast, the missed visit and appointment adherence measures may have greater sensitivity in accounting for disease severity as the frequency of scheduled visits reflects the clinician's assessment of the requisite number of visits and visit interval for a given patient during an observation period of interest. Accordingly, implicit in these measures is an assumption that visit frequency reflects, in part, the disease severity and stage of treatment for each individual patient being studied. The constancy measure has the capacity to account for severity and stage of treatment through variation of the time interval (e.g., range 3–6 months) during which the assessment of completed visits is evaluated. For example, for patients initiating clinical care or antiretroviral therapy, a 3-month interval may be most appropriate, whereas a 6-month interval may be indicated for patients on a stable antiretroviral therapy regimen with long-standing HIV viral load suppression and a high CD4 count.

Future directions

A relative paucity of research has focused on the individual and population health implications of differential engagement in HIV care. With growing emphasis on “test and treat” approaches to HIV prevention,21 recently referred to as testing, linkage to care plus (TLC+),28 there is a clear need for additional engagement in HIV care research. As HIV care is increasingly team-based with nonprescribing health care professionals taking on expanded roles in direct patient care, future research should evaluate the impact of such visits and their inclusion in HIV retention measures on patient outcomes. Furthermore, with increased emphasis on the patient-centered medical home, the importance engagement in care has taken on increased importance not only for HIV care,29 but for long-term disease management more broadly. Accordingly, the principles and considerations for measuring retention in HIV care described herein may have more widespread application in the future.

Conclusions

In recent years, recognition of the contribution of engagement in care to individual and population health of patients with HIV infection has resulted in the need for a framework defining how retention is measured.24 This article provides a synthesis of the most commonly used measures of retention in HIV care, highlights their methodological and conceptual strengths and limitations, and suggests situations in which certain measures may be preferred over others. As has been noted for antiretroviral medication adherence, there is no gold standard to measure retention in care,30 and consideration of the advantages and limitations of each measure, particularly in the context of the desired application, should guide selection of a retention measure.

Acknowledgments

These data were presented, in part, at a workshop at the 4th International Conference on HIV Treatment Adherence, Miami, Florida, April 5–7, 2009.

This study was supported by grant K23MH082641 (M.J.M.) and grant R34MH074360 (TPG) from the National Institute of Mental Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2003. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lurie N. Dubowitz T. Health disparities and access to health. JAMA. 2007;297:1118–1121. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.10.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bozzette SA. Berry SH. Duan N, et al. The care of HIV-infected adults in the United States. HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study Consortium. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1897–1904. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812243392606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleming P. Byers R. Sweeney P. Daniels D. Karon J. Jansen R. HIV Prevalence in the United States, 2000 [Abstract 11]; Program and Abstracts of the 9th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Seattle, WA. Feb 24–28;2002 . [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg MB. Safren SA. Mimiaga MJ. Grasso C. Boswell S. Mayer KH. Nonadherence to medical appointments is associated with increased plasma HIV RNA and decreased CD4 cell counts in a community-based HIV primary care clinic. AIDS Care. 2005;17:902–907. doi: 10.1080/09540120500101658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giordano TP. Gifford AL. Clinton White A, et al. Retention in care: A challenge to survival with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1493–1499. doi: 10.1086/516778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giordano TP. White AC., Jr. Sajja P, et al. Factors associated with the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients newly entering care in an urban clinic. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:399–405. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200304010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lucas GM. Chaisson RE. Moore RD. Highly active antiretroviral therapy in a large urban clinic: Risk factors for virologic failure and adverse drug reactions. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:81–87. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-2-199907200-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mugavero MJ. Lin HY. Allison JJ, et al. Racial disparities in HIV virologic failure: Do missed visits matter? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:100–108. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818d5c37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mugavero MJ. Lin HY. Willig JH, et al. Missed visits and mortality among patients establishing initial outpatient HIV treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:248–256. doi: 10.1086/595705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park WB. Choe PG. Kim SH, et al. One-year adherence to clinic visits after highly active antiretroviral therapy: A predictor of clinical progress in HIV patients. J Intern Med. 2007;261:268–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ulett KB. Willig JH. Lin HY, et al. The therapeutic implications of timely linkage and early retention in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2009;23:41–49. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arici C. Ripamonti D. Maggiolo F, et al. Factors associated with the failure of HIV-positive persons to return for scheduled medical visits. HIV Clin Trials. 2002;3:52–57. doi: 10.1310/2XAK-VBT8-9NU9-6VAK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cabral HJ. Tobias C. Rajabiun S, et al. Outreach program contacts: Do they increase the likelihood of engagement and retention in HIV primary care for hard-to-reach patients? AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2007;21(Suppl 1):S59–67. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giordano TP. Visnegarwala F. White AC, Jr., et al. Patients referred to an urban HIV clinic frequently fail to establish care: Factors predicting failure. AIDS Care. 2005;17:773–783. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331336652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keruly JC. Conviser R. Moore RD. Association of medical insurance and other factors with receipt of antiretroviral therapy. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:852–857. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mugavero MJ. Improving engagement in HIV care: What can we do? Top HIV Med. 2008;16:156–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marks G. Crepaz N. Senterfitt JW. Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: Implications for HIV prevention programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:446–453. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Metsch LR. Pereyra M. Messinger S, et al. HIV transmission risk behaviors among HIV-infected persons who are successfully linked to care. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:577–584. doi: 10.1086/590153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen MS. Gay C. Kashuba AD. Blower S. Paxton L. Narrative review: Antiretroviral therapy to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV-1. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:591–601. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-8-200704170-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dieffenbach CW. Fauci AS. Universal voluntary testing and treatment for prevention of HIV transmission. JAMA. 2009;301:2380–2382. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quinn TC. Wawer MJ. Sewankambo N, et al. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Rakai Project Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:921–929. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aberg JA. Kaplan JE. Libman H, et al. Primary care guidelines for the management of persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus: 2009 update by the HIV medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:651–681. doi: 10.1086/605292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horstmann E. Brown J. Islam F. Buck J. Agins BD. Retaining HIV-infected patients in care: Where are we? Where do we go from here? Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:752–761. doi: 10.1086/649933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melnikow J. Kiefe C. Patient compliance and medical research: Issues in methodology. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9:96–105. doi: 10.1007/BF02600211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olatosi BA. Probst JC. Stoskopf CH. Martin AB. Duffus WA. Patterns of engagement in care by HIV-infected adults: South Carolina, 2004–2006. AIDS. 2009;23:725–730. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328326f546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evaluating the contribution of ancillary services in improving access to primary care in the United States under the Ryan White CARE Act AIDS Care 200214Suppl 13–136.11798401 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Project Inform. TLC+: Testing, Linkage to Care and Treatment. www.projectinform.org/tlc+/ [May 13;2010 ]. www.projectinform.org/tlc+/

- 29.Saag MS. Ryan White: An unintentional home builder. AIDS Reader. 2009;19:166–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chesney MA. The elusive gold standard. Future perspectives for HIV adherence assessment and intervention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(Suppl 1):S149–155. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243112.91293.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]