Abstract

Background

Risk drinking for women is defined by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) as >7 drinks per week or >3 drinks per occasion. This study compares the T-ACE screening tool and the medical record for identification of risk drinking by 611 women receiving outpatient treatment for diabetes, hypertension, infertility, or osteoporosis in Boston, Massachusetts, between February 2005 and May 2009.

Methods

All subjects completed a diagnostic interview about their health habits, and medical records were abstracted. Calculations were weighted to reflect the oversampling of risk drinking women.

Results

T-ACE-positive women (n = 419) had significantly more drinks per drinking day (2.1 vs. 1.6, p < 0.0001) and a trend toward more binges (6.3 vs. 3.8, p = 0.07) but similar percent drinking days and risk drinking weeks compared with those with negative screens (n = 192). Among the 521 (85%) medical records available, 46% acknowledged alcohol use, 25% denied use, and 29% were silent. The rates of abstinence among women were 2%, 17%, and 4%, respectively. Significantly more women were risk drinkers (63%) and had current alcohol use disorders (12%) when their medical records acknowledged alcohol use.

Conclusions

The main findings of this study are that neither the T-ACE nor the medical record was especially effective in identifying risk drinking by the women enrolled in the study. The identification of risky or heavy alcohol use in women, particularly if they have health problems exacerbated by alcohol, is desirable and represents an area of improvement for patients and providers alike.

Introduction

Risky or hazardous drinking has been defined as >7 drinks per week or >3 drinks per occasion for women.1 Sensible drinking limits (SDL) were established by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and reflect the higher risk of adverse effects from alcohol in women.2 An estimated 13% of American women will have >7 drinks per week, and 8% will have an average of 2.9 binges consisting of 6.9 drinks in the preceding 30 days.3 The traditional gender gap in alcohol use, abuse, and dependence is closing among the younger cohorts in the United States and elsewhere, so that even more women are at risk.4,5 In addition, the frequency of alcohol use in middle-aged and older adults is also increasing, with at-risk and binge drinking being reported often.6

Given the association between these risky patterns of use and adverse health consequences, screening questionnaires have been recommended to increase recognition by healthcare providers.7 Although the Cut-down, Annoy, Guilt, Eye-opener (CAGE) measure is among the best known by clinicians, some limitations have been reported. For example, the CAGE has been found to be relatively insensitive in predominantly white female populations, in adolescents, and for risky drinking.8–10 Indeed, the search for a risky drinking screen in the medical setting has been compared with the quest for the Holy Grail.11

The T-ACE is an example of an alcohol screening questionnaire that is based on the CAGE but modified to improve the identification of risk drinking during pregnancy.12 The T-ACE identifies ≥90% of potential pregnant risk drinkers.13 The T-ACE substitutes the Guilt question from the CAGE with a question about Tolerance to the effects of alcohol. The T-ACE questions are shown in Table 1. Because of its brevity and ease of scoring, the T-ACE is appealing and has since been evaluated in other samples beyond pregnant women. For instance, the T-ACE was considered positive with any score >0 and was combined with other risk factors (including regular use of two or more over-the-counter drugs, consumption of large amounts of coffee, and use of alcohol to fall asleep) to predict alcohol drinking on at least 15 days/month in a study of 135 women aged ≥60.14 A primary care study of 300 adults used a modified version of the T-ACE (by assigning only 1 point to the Tolerance question) and compared it with the diagnosis of alcohol abuse or dependence.15 A final example involves 360 women seeking gynecological care who completed a series of alcohol and drug use screening measures and provided information about their use of alcohol and drugs. In this study, 24% had positive T-ACE screens, and 1% were identified by their physicians as having alcohol problems.16 These evaluations have demonstrated the application of the T-ACE in more diverse groups, but whether the T-ACE can be used even more generally awaits further confirmation, particularly as there were modifications in the scoring.

Table 1.

The T-ACE Questions

| T | How many drinks does it take to make you feel high (Tolerance)? |

| A | Have people Annoyed you by criticizing your drinking? |

| C | Have you ever felt you ought to Cut down on your drinking? |

| E | Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or get rid of a hangover (Eye-opener)? |

The T-ACE is positive with a total of ≥2 points. Two points are assigned if a person answers >2 drinks to the Tolerance question. An affirmative response to the Annoyed, Cut down, or Eye-opener question is given 1 point.12

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the T-ACE and the providers' impressions of alcohol use documented in the medical record in a sample of 611 women receiving outpatient treatment for diabetes, hypertension, infertility, or osteoporosis between February 2005 and May 2009 in Boston, Massachusetts. These are medical problems whose successful management is complicated by excessive alcohol use (e.g., heavy alcohol use is significantly and positively related to fasting blood glucose, increases the risk of hypertension, is associated with increases in infertility caused by ovulatory factors, and may compromise bone health).17–20 Both the T-ACE and the providers' impressions were compared with the findings from the diagnostic interview, which include mean drinks per drinking day, percent drinking days, number of binge episodes, and number of weeks exceeding NIAAA SDL for women in the previous 6 months. Current and lifetime alcohol and other substance use disorders according to DSM-IV diagnostic criteria were also obtained. We predicted that the T-ACE would identify more women at risk and also anticipated that providers' impressions would be accurate because all the women had medical problems potentially exacerbated by alcohol use.

Materials and Methods

The Women's Health Habits Study took place at the Brigham and Women's Hospital between February 2005 and May 2009. Thirty-three hundred eleven women from the outpatient clinics of the Brigham and Women's Hospital (80%) and its surrounding community (20%) completed the Health Habits Survey. The Health Habits Survey was embedded with the T-ACE and quantity-frequency questions about usual alcohol use. Eligibility for further participation included subjects' agreement to have their medical problems confirmed by their physicians, authorization for medical records release, no current pregnancy, and any amount of alcohol use in the past 6 months. Six hundred seventy-eight (22%) declined to participate further after the initial survey.

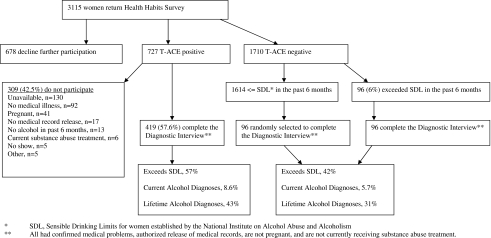

Seven hundred twenty-seven women (23%) were T-ACE positive using the standard cut-off point.12 Of the 727 T-ACE-positive women, 309 (42.5%) were excluded because 130 (42%) were unavailable, 92 (30%) did not have one of the study diseases confirmed, 41 (13%) were pregnant, 17 (6%) declined to authorize medical records release, 13 (4%) consumed no alcohol in the past 6 months, 6 (2%) were in alcohol treatment, and the remaining 10 (3%) were excluded for other reasons. The remaining 419 T-ACE-positive women all completed the diagnostic interview.

Seventeen hundred ten women (55%) were T-ACE negative. Of these 1710, 96 (6%) had risk drinking exceeding the NIAAA SDL in the past 6 months, and all completed the diagnostic interview after satisfying eligibility criteria. Among the 1614 (94%) T-ACE-negative women who did not exceed SDL, a random sample of 96 was selected to complete the diagnostic interview. Figure 1 summarizes the study flow based on the recommendations of the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) initiative for studies of diagnostic accuracy.21

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart.

All completed the diagnostic interview, which consisted of several measures of current and past alcohol use and general health in the month after the Health Habits Survey. These included (1) the alcohol and drug abuse modules from the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV to generate current and lifetime alcohol and drug disorder diagnoses,22 (2) the alcohol timeline followback (TLFB) interview to obtain estimates of daily drinking for the previous 6 months,23 and (3) the MOS 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36),24 a measure of general health status that yields two summary measures of physical and mental health functioning. In addition, the participants' medical records were reviewed to abstract information about providers' impressions of participants' alcohol use. The diagnostic interview and medical record abstractions were completed by trained research staff and medical professionals. It was impossible to blind them to the results of the initial Health and Habits Survey for logistic reasons. Subjects received an honorarium of $50.00 for their participation, commensurate with the community standard.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Partners Institutional Review Board, responsible for human subject research conducted by the staff of the Brigham and Women's Hospital. In addition, a federal Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained (No. AA-30-2005).

Data analysis

All analyses were carried out using the SAS statistical package (version 9.1). Simple descriptive statistics were calculated and are reported as percentages, means, standard deviations (SD), and ranges, as appropriate. Statistical differences in demographic characteristics between the groups were obtained using t tests for continuous measures and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Four outcomes were measured: (1) drinks per drinking day, (2) percent drinking days, (3) number of binge episodes, and (4) number of weeks exceeding NIAAA SDL. These measures were calculated using the TLFB for the 6-month period before study enrollment; t tests were used for between-group comparisons for the positive and negative T-ACE screens. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the four drinking measures between the three-level medical record categories (alcohol use, no alcohol use, and no mention).

Sensitivity (true positive rate) and specificity (true negative rate) values for the T-ACE, all available medical records, and a subset of medical records with specific notations were calculated. Three dichotomous measures were used as gold standards: exceeding any NIAAA SDL, lifetime DSM-IV alcohol use disorders, and current DSM-IV alcohol use disorders. Because our study design sampled more heavily among women who were T-ACE positive and those who were T-ACE negative but exceeded SDL, our calculations of sensitivity and specificity were weighted. For sensitivity, we calculated the sensitivity within each of the three subgroups (T-ACE positive, T-ACE negative but within SDL, T-ACE negative but beyond SDL) and then weighted according to the estimated prevalence of gold standard positive woman in each subgroup. Analogous weightings were carried out for specificity. Logistic regression with each assessment as the outcome variable was used to calculate the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) for each ordinal scale.25 Values can range from 0.5 to 1; whereas an area of 1 indicates a perfect test, an area of 0.5 means that the test performs no better than chance.26 Again, to adjust for the sampling scheme, the logistic regression models were weighted according to the sampling fractions.

Results

Overall, 419 women had positive T-ACE scores, and 192 were T-ACE negative. The screen positive and negative women were similar in terms of age, racial and ethnic background, employment status, educational attainment, and body mass index (BMI.) The average participant was in her mid-40s, Caucasian, employed, had a 4-year college degree, and had an overweight BMI. The T-ACE-positive women were more likely to be single or never married (p = 0.01), and less likely to have children (p = 0.03). The groups differed in terms of medical condition represented, with more infertile patients in the screen positive group and more osteoporosis patients in the screen negative group (p = 0.01). Although both groups had average physical component summary scores (PCS) and mental component summary scores (MCS), the screen negative group had a higher MCS score (p = 0.03). Both the PCS and MCS have a mean of 50 and an SD of 10 in the general U.S. population. Higher scores indicate better function.27 There was a trend for a higher proportion of the screen positive women to smoke cigarettes, in comparison to the screen negative women (p = 0.07). Table 2 summarizes the demographic and clinical backgrounds of the participants.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | T-ACE positive (n = 419) | T-ACE negative (n = 192) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean years (SD) | 45.01 (13.3) | 47.15 (13.2) | 0.06 |

| Race | |||

| Asian | 10 (2.4%) | 9 (4.7%) | 0.13 |

| African American | 95 (22.8%) | 35 (18.4%) | |

| Caucasian | 313 (74.8%) | 144 (76.3%) | |

| Other | 0% | 1 (1%) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 23 (5.5%) | 7 (3.7%) | 0.33 |

| Employed | |||

| Yes | 271 (67%) | 121 (66%) | 0.81 |

| No | 135 (33%) | 63 (34%) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 221 (53.1%) | 101 (52.6%) | 0.01 |

| Widowed | 13 (3.1%) | 8 (4.2%) | |

| Divorced/separated | 57 (13.7%) | 43 (22.4%) | |

| Single/never married | 126 (30.1%) | 39 (20.8%) | |

| Children | |||

| Yes | 200 (48%) | 110 (58%) | 0.03 |

| Education | |||

| High school | 58 (14%) | 32 (16.7%) | 0.71 |

| Part college | 53 (12.7%) | 23 (12%) | |

| 2 year college | 46 (11.1%) | 19 (10%) | |

| 4 year college | 114 (27.4%) | 46 (24%) | |

| Part graduate school | 30 (7.2%) | 10 (5.2%) | |

| Graduate/professional | 116 (27.6%) | 61 (32.3%) | |

| Condition | |||

| Hypertension | 133 (31.6%) | 61 (32.1%) | 0.01 |

| Diabetes | 86 (20.6%) | 35 (18.1%) | |

| Osteoporosis | 67 (16%) | 51 (26.4%) | |

| Infertility | 163 (31.8%) | 45 (23.3%) | |

| BMI | |||

| Mean (SD) | 27.44 (7.4) | 27.33 (8.11) | 0.87 |

| SF-36 | |||

| PCS | 49.88 (9.7) | 48.89 (11.1) | 0.28 |

| MCS | 45.55 (10.9) | 47.53 (9.7) | 0.03 |

| Cigarettes | |||

| Yes | 59 (14%) | 17 (9%) | 0.07 |

| Exercise | |||

| Yes | 255 (62%) | 124 (65%) | 0.48 |

BMI, body mass index; MCS, mental component summary; PCS, physical component summary; SD, standard deviation, SF-36, 36-item Short Form Survey.

Of 611 medical records, 521 (85.3%) were available for review. In general, information about alcohol use on the medical record fell into one of three categories: alcohol use acknowledged (n = 241, 46%), alcohol use denied (n = 130, 25%), or no mention of alcohol at all (n = 150, 29%). The medical record rarely reported quantity and frequency of use and instead relied on such terms as “social drinking” or “none.”

Alcohol use in past 6 months

Alcohol use in the past 6 months was measured by drinks per drinking day, percent drinking days, number of binges, and number of weeks exceeding NIAAA SDL (Table 3). The four drinking outcomes were compared between the T-ACE-positive and T-ACE-negative groups. The T-ACE-positive women had more mean drinks per drinking day, 2.1 (SD 1.4) vs. 1.6 (SD 1.4) (p < 0.0001), and more mean binges in the previous 6 months, 6.3 (SD 21.0) vs. 3.8 (SD 19.0) (p = 0.07), compared with the T-ACE-negative women. Both groups had similar mean percent drinking days (22% vs. 20%, p = 0.42) and mean risk drinking weeks, when NIAAA SDL were exceeded, 3.6 (SD 7.3) vs. 2.7 (SD 6.3) (p = 0.14).

Table 3.

Alcohol Use in Previous 6 Months

| |

T-ACE positive |

T-ACE negative |

|

Medical record: alcohol |

Medical record: no alcohol |

Medical record: not mentioned |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 419 | n = 192 | p value | n = 241 | n = 130 | n = 150 | p value | |

| D/DD | 2.1 (1.4) | 1.6 (1.4) | <0.0001 | 2.1 (1.3)a | 1.6 (1.3)a | 1.9 (1.2) | 0.003 |

| % DD | 22% | 20% | 0.42 | 28%c | 11%c | 21%c | <0.0001 |

| Binges | 6.3 (21.0) | 3.8 (13.4) | 0.07 | 7.6 (24.4)a | 3.6 (11.6) | 2.8 (7.6)a | 0.02 |

| Risk drinking weeks | 3.6 (7.3) | 2.7 (6.3) | 0.14 | 4.5 (7.9)a, b | 1.6 (5.3)b | 2.8 (6.3)a | 0.0003 |

Pair significant difference.

Pair significant difference.

All pairs significant difference.

D/DD, drinks per drinking day; %DD, percent drinking days.

Among the 241 women whose medical records acknowledged alcohol use, 5(2%) consumed no alcohol according to the diagnostic interview. The drinkers in this group had a mean of 2.1 drinks per drinking day, 28% drinking days, a mean of 7.6 binges in the prior 6 months, and 4.5 risk drinking weeks. Among the 130 women whose medical records indicated no alcohol use, 22 (17%) confirmed no alcohol use during the diagnostic interview. Otherwise, the “no alcohol group” had an average of 1.6 drinks per drinking day, 11% drinking days, 3.6 binges, and 1.6 risk drinking weeks. The differences in drinking between the two groups were all statistically significant (p < 0.05). Finally, the group of 150 women for whom no information about their use was recorded on the medical records had an average of 2.0 drinks per drinking day, 21% drinking days, 2.8 binges, and 2.8 risk drinking weeks. Only 6 of the 150 (4%) women reported no alcohol use at all on the diagnostic interview.

Summary measures of alcohol use

Among the 611 participants overall, 318 (52%) exceeded recommended SDL in the past 6 months, 47 (7.7%) had current DSM-IV alcohol use disorders, and 240 (39%) satisfied criteria for lifetime DSM-IV alcohol use disorders. The rates of these three summary measures of alcohol use, which reflect a range of alcohol problem severity from less to more severe, were compared among the women with positive and negative T-ACE scores and medical records (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary Measures of Alcohol Use

| |

T-ACE (n = 611) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | p value | |

| Drinking > NIAAA SDL | 57% | 42% | 0.0005 |

| Current alcohol diagnosis | 8.6% | 5.7% | 0.22 |

| Lifetime alcohol diagnosis | 43% | 31% | 0.003 |

| Medical records with alcohol use documented (n = 371) | |||

| Acknowledged | Denied | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drinking > NIAAA SDL | 63% | 35% | <0.0001 |

| Current alcohol diagnosis | 12% | 4% | 0.008 |

| Lifetime alcohol diagnosis | 41% | 35% | 0.27 |

| All medical records (n = 521) | |||

| Acknowledged | Denied/Unknown | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drinking > NIAAA SDL | 63% | 43% | <0.0001 |

| Current alcohol diagnosis | 12% | 5% | 0.004 |

| Lifetime alcohol diagnosis | 41% | 37% | 0.32 |

NIAAA, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; SDL, sensible drinking limits.

More women with positive T-ACE scores exceeded NIAAA SDL (57% vs. 42%, p = 0.0005) and satisfied DSM-IV criteria for lifetime alcohol use disorders (43% vs. 31%, p = 0.003) compared with those with negative T-ACE scores. There was no difference in the rates (8.6% vs. 5.7%, p = 0.22) of current alcohol use disorders by T-ACE score. More women whose alcohol use was acknowledged in the medical records exceeded NIAAA SDL (63% vs. 35%, p < 0.0001) and satisfied DSM-IV criteria for current alcohol diagnoses (12% vs. 4%, p = 0.008) than women whose medical records indicated no alcohol use. There was no significant difference in the rates of lifetime alcohol diagnoses (41% vs. 35%, p = 0.27) among the women whose medical records recorded alcohol use. When all available medical records were compared, including those that did not mention alcohol use, more women whose medical records reported consumption exceeded NIAAA SDL (63% vs. 43%, p < 0.0001) and satisfied current alcohol use disorder diagnoses (12% vs. 5%, p = 0.004) than those women whose records either indicated no use or were silent.

Measures of merit: T-ACE and medical record

The AUROC, sensitivity, and specificity of the T-ACE and the medical record compared with the three summary measures of alcohol use (any drinking exceeding NIAAA SDL, current DSM-IV alcohol use disorders, and lifetime DSM-IV alcohol use disorders) are summarized in Table 5. With regard to any drinking exceeding SDL, the T-ACE and the medical record (with alcohol use notations) had the largest AUROC of 0.63 and comparable sensitivity and specificity. When current alcohol diagnoses were considered, the AUROC for the T-ACE (0.68) was greater than that for either category of medical record (0.61, 0.62). The medical record with alcohol use notations was the most sensitive (0.83) and most specific (0.47) for current alcohol diagnoses, compared with the T-ACE, and the more inclusive category of all medical records. For lifetime alcohol diagnoses, the T-ACE was better than either category of medical record; its AUROC was 0.64, sensitivity was 0.75, and specificity was 0.36. The AUROC for either category of medical record was about 0.5 or chance.

Table 5.

Predictive Values of T-ACE and Medical Record

| |

TACE n = 611 |

Medical records with/notations n = 371 |

All medical records n = 521 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | AUROC | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUROC | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUROC | |

| Drinking > NIAAA SDL | 0.75 | 0.38 | 0.63 | 0.82 | 0.36 | 0.63 | 0.44 | 0.24 | 0.59 |

| Current alcohol diagnosis | 0.77 | 0.32 | 0.68 | 0.83 | 0.47 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.3 | 0.62 |

| Lifetime alcohol diagnosis | 0.75 | 0.36 | 0.64 | 0.5 | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.36 | 0.28 | 0.52 |

AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve.

Discussion

The main findings of this study are that neither the T-ACE nor the medical record was especially effective in identifying risk drinking by the women enrolled in the study. Risk drinkers were oversampled because they all had medical problems whose management could be exacerbated by alcohol use. Higher levels of daily use, binges, and weeks exceeding NIAAA SDL were found among women who had positive T-ACE screens and for whom medical records documented alcohol use. All patterns of use were significantly higher among women with positive medical records; women with positive T-ACE screens had significantly higher average drinks per drinking day and a trend toward more binges than women with negative T-ACEs.

Among the women for whom the medical record indicated no alcohol use, only 17% were abstinent. Although these women had low overall patterns of use (1.6 drinks on 11% of days), they did have an average of 3.6 binge episodes in the 6 months before study enrollment. Twenty-nine percent of the available medical records made no comment about use; only 4% of the women in this category were abstinent. The remaining 96% averaged 1.9 drinks on 21% of days and had about 3 binges in the 6 months before study enrollment.

Explanations for the discrepancies between information documented on the medical record and what participants reported during the diagnostic interview are speculative. Perhaps in some cases, the patient or her doctor decided that her level of use was insignificant, resulting in a notation of no alcohol use or no comment at all. Possible reasons for the absence of information on the medical record in other circumstances include wishes to preserve the patient's privacy, subsequent documentation of alcohol use, lack of apparent clinical relevance, or assessment of use without documentation.

Potential limitations of the study include assembly bias, self-report, reliance on medical charts, and interviewers being unblinded. Particularly motivated women may have enrolled in the study. Some participants may not have provided accurate drinking information to study interviewers or their doctors in an effort to look good. They reported only on the past 6 months of alcohol drinking. Medical records simply may have been incomplete. For example, a study of observed vs. documented physician assessment of pain by emergency physicians found that whereas physicians almost always assessed and treated pain, these efforts were infrequently recorded.28 Finally, interviewers were not blinded to the initial survey results; blinding would have rendered the study impossible logistically. However, the interviewers administered standard, structured, impartial measures to render criterion-based results.

Overall, participants' measures of physical and mental health were similar to the norms established for women aged 45–54 from the general U.S. population, where PCS is 49.37 and MCS is 50.32.26 The MCS score for the T-ACE-positive women was lower than that of the T-ACE-negative women, 45.6 (SD 10.9) vs. 47.5 (SD 9.7) (p = 0.03). The clinical significance of this difference, if any, is unknown, although when combined with the high average BMI in the T-ACE-positive group, some concern about depression might be raised. A study of 429 African American women found that overweight and alcohol use were independent predictors of depressed mood after controlling for demographic factors.29

Whereas risk drinking and more serious forms of alcohol use by women were once considered to be rare and unusual, all available evidence suggests that women are catching up to male patterns of use.30 Moreover, there is increasing appreciation for related adverse health consequences, such as the association between moderate alcohol use and increased risk of breast cancer.31 Women in this study all had medical problems potentially exacerbated by excessive alcohol use; thus, accurate recognition of their patterns of intake might contribute to improved health. Although 241 women were identified on their medical records as drinkers, it is not known if problematic patterns of use were appreciated by their physicians and then addressed.

The consistent use of screening instruments in primary care and other medical settings to facilitate recognition of alcohol use has been recommended to stimulate subsequent patient and provider dialogue.32 The choice of the screening measure needs to include consideration of its purpose—to identify risky drinking or drinking at levels that satisfy diagnostic criteria for current or lifetime abuse or dependence. At this time, the 10-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) or possibly the AUDIT Alcohol Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C) seems promising, particularly as one large observational study found that higher AUDIT-C scores were associated with medication nonadherence.7,33,34 The identification of risky or heavy alcohol use in women, particularly if they have health problems exacerbated by alcohol, is desirable and represents an area of improvement for patients and providers alike.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants R01 AA 014678 and K24 AA 00289 to G.C.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Helping patients who drink too much. A clinician's guide, updated 2005 edition. Jan, 2007. NIH Publication No. 07-3769.

- 2.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol—An important women's health issue. Alcohol Alert No. 62, July 2004. pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/aa61/aa62.htm. [Mar 21;2010 ]. pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/aa61/aa62.htm

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sociodemographic differences in binge drinking among adults—14 states, 2004. MMWR. 2009;58:301–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keyes KM. Brant DF. Hasin DF. Evidence for a closing gender gap in alcohol use, abuse, and dependence in the United States population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilmore IT. Excessive drinking in young women: Not just a lifestyle disease. BMJ. 2008;336:952–953. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39520.716863.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blazer DG. Wu LT. The epidemiology of at-risk and binge drinking among middle-aged and elderly community adults: National survey on drug use and health. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:1162–1169. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kriston L. Holzel L. Weiser AK. Berner MM. Harter M. Meta-analysis: Are 3 questions enough to detect unhealthy alcohol use? Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:879–888. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-12-200812160-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradley KA. Boyd-Wickizer J. Powell SH. Burman ML. Alcohol screening questionnaires in women: A critical review. JAMA. 1998;280:166–171. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knight JR. Sherritt L. Harris SK. Gates ED. Chang G. Validity of brief alcohol screening tests among adolescents: A comparison of the AUDIT, POSIT, CAGE, and CRAFFT. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:67–73. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000046598.59317.3A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiellin DA. Reid RM. O'Connor PG. Screening for alcohol problems in primary care: A systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1977–1989. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.13.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleming MF. In search of the Holy Grail for the detection of hazardous drinking. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:321–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sokol RJ. Martier SS. Ager JW. The T-ACE questions: Practical prenatal detection of risk drinking. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:863–871. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sokol RJ. Delaney-Black V. Nordstrom B. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. JAMA. 2003;22:2296–2999. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.22.2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevenson JS. Masters JA. Predictors of alcohol use misuse and abuse in older women. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2005;37:329–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2005.00057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McQuade WH. Levy SM. Yanek LR. Davis SW. Liepman MR. Detecting symptoms of alcohol abuse in primary care settings. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:814–821. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.9.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupman AE. Svikis D. McCaul ME. Anderson J. Santora PB. Detection of alcohol and drug problems in an urban gynecology clinic. J Reprod Med. 2002;47:404–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klatsky AL. Gunderson EP. Kipp H. Udaltsova N. Friedman GD. Higher prevalence of systemic hypertension among moderate alcohol drinkers: An exploration of the role of underreporting. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67:421–438. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chew LD. Nelson KM. Young BA. Bradley KA. Association between alcohol consumption and diabetes preventive practices. Fam Med. 2005;37:589–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Homan GF. Davies M. Norman R. The impact of lifestyle factors on reproductive performance in the general population and those undergoing infertility treatment: A review. Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13:209–223. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berg KM. Kunins HV. Jackson JL, et al. Association between alcohol consumption and both osteoporotic fracture and bone density. Am J Med. 2008;121:406–418. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bossuyt PM. Reistma JB. Bruns DE, et al. Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: The STARD initiative. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:40–44. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.First MB. Spitzer RL. Gibbon M. Williams JBW. Biometrics Research Department. New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1996. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders—Patient edition (SCID-I/P, version 2.0) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sobell LC. Sobell MB. Timeline followback: A technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption. In: Allen J, editor; Litten RZ, editor. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biological methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ware JE. Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36 Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:MS253–MS265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hosmer DW. Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2nd. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanley JA. McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ware JE. Kosinski M. 2nd. Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric Incorporated; 2005. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: A manual for users of version 1; p. 88. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chisholm CD. Weaver CS. Whenmouth LF. Giles B. Brizendine EJ. A comparison of observed versus documented physician assessment and treatment of pain: The physician record does not reflect the reality. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:383–389. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siegel JM. Yancey AK. McCarthy WJ. Overweight and depressive symptoms among African American women. Prev Med. 2000;31:232–240. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiechelt SA. Introduction to the Special Issue: International perspectives on women's substance use. Subst Use Misuse. 2008;43:973–977. doi: 10.1080/10826080801914188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang SM. Lee IM. Manson JE. Cook NR. Willett WC. Buring JE. Alcohol consumption and breast cancer risk in the Women's Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:667–676. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grucza RA. Przybeck TH. Cloninger CR. Screening for alcohol problems: An epidemiological perspective and implications for primary care. Mo Med. 2008;105:67–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bryson CL. Au DH. Sun H. Williams EC. Kivlahan DR. Bradley KA. Alcohol screening scores and medication non-adherence. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:795–803. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-11-200812020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bush K. Kivlnaha DR. McDonell MB. Fihn SD. Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C) Arch Int Med. 1998;158:1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]