Abstract

In the current study, a 2D multi-phase MR displacement encoding with stimulated echoes (DENSE) imaging and analysis method was developed for direct quantification of Lagrangian strain in the mouse heart. Using the proposed method, less than 10 ms temporal resolution and 0.56 mm in-plane resolution were achieved. A validation study that compared strain calculation by DENSE and by MR tagging showed high correlation between the two methods (R2 > 0.80). Regional ventricular wall strain and twist were characterized in mouse hearts at baseline and under dobutamine stimulation. Dobutamine stimulation induced significant increase in radial and circumferential strains and torsion at peak-systole. A rapid untwisting was also observed during early diastole. This work demonstrates the capability of characterizing cardiac functional response to dobutamine stimulation in the mouse heart using 2D multi-phase MR DENSE.

Keywords: Myocardial wall strain, displacement encoding, ventricular torsion, β-adrenergic stimulation

Introduction

Genetically manipulated mouse models have gained increasing popularity as a prominent tool for the understanding of human cardiac diseases in the past decade (1). Abnormal myocardial wall strain frequently precedes global functional alterations at early diseased stage. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques, such as myocardial tissue tagging (2-5), harmonic phase (HARP) MRI (6-8), phase contrast (PC) imaging (9, 10), and displacement-encoded imaging (11-13), allow quantitative evaluation of regional myocardial wall motion noninvasively. When applied to genetically manipulated mouse models, these methods provide new opportunities to explore the underlying molecular and cellular mechanisms responsible for functional alterations (14, 15).

MRI tagging has provided the first opportunity to assess regional ventricular function in mice (5, 16, 17). However, current methods of manual or semi-automatic imaging analysis demand substantial user input and post-processing time. In addition, the low tagging resolution hampers the quantification of transmural strain and twist in the mouse heart. Harmonic phase (HARP) analysis was proposed for rapid and automatic strain quantification of spatial modulation of magnetization (SPAMM)-tagged images (6-8). However, HARP analysis offers limited spatial resolution due to the filtering of the harmonic peaks in k-space. PC imaging provides high spatial resolution by pixel-wise encoding of tissue velocity in its phase images. However, strain quantification through the integration of velocity measurements in general is subject to error propagation, unless other algorithms such as bidirectional motion integration are used (18).

The displacement encoding with stimulated echoes (DENSE) method encodes tissue displacement directly in the phase images. It thus allows strain quantification with high spatial resolution. Single phase 2D and 3D DENSE methods have been developed for strain measurements in normal and post-infarct mouse hearts at end-systole (13, 19). However, multi-phase DENSE imaging of a mouse heart is still challenging because of limited SNR associated with stimulated echoes and fast heart rate (20, 21). In addition, correct and robust phase-unwrapping is critically important for accurate strain quantification. The process of phase-unwrapping may require sophisticated algorithms that use both spatial and temporal evolution of phase in multi-phase DENSE images (22).

In the present study, we aimed at developing a 2D multi-phase MR DENSE imaging and analysis method for direct assessment of myocardial wall strain in mouse hearts. Validation study was performed by comparing myocardial strain calculated from MR DENSE with that from MR tagging analysis. To explore the capacity of DENSE in delineating functional changes in the mouse heart, increase in strain and torsion under dobutamine stimulation was also quantified using the proposed method. These data demonstrate that multi-phase MR DENSE can provide comprehensive evaluation of ventricular function in mice at both baseline and high cardiac workload.

Materials and Methods

Animal Preparation and Monitoring

Seven 2-month-old male C57BL/6 mice were imaged at baseline for method development and validation. Additional seven 6-month-old male FVB mice were imaged both at baseline and during dobutamine infusion to explore the capacity of the current method in quantifying functional increase due to β-adrenergic stimulation.

Animals were anesthetized with 1% isoflurane in O2 by nose cone and placed into the coil in prone position. Electrocardiography (ECG) electrodes were attached to the left paw and the right leg. An MR-compatible small animal gating and monitoring system was used for ECG gating and monitoring of vital signs (SA Instruments, Stony Brook, NY). A rectal temperature probe was inserted to monitor the body temperature. The body temperature was maintained at 35.3 ± 0.4°C by blowing hot air into the magnet using a small rodent feedback-control heater system (SA Instruments, Stony Brook, NY). Respiratory pad was placed under the chest wall for monitoring respiratory patterns. Respiratory gating was combined to ECG gating to minimize respiratory motion artifact when needed. Data acquisition was triggered at every other heartbeat.

For those mice that underwent dobutamine stimulation, a 26G-3/4″ Abbocath®-T catheter (TW Medical, Lago Vista, TX) was inserted into the tail vein and connected to an infusion pump (Braintree Scientific, Braintree, MA) for dobutamine infusion. Following the acquisition of DENSE images at baseline, the mouse was continuously infused with dobutamine at a dose of 40 μg/min/kg through tail vein catheterization. After 10∼15 minutes of stabilization, another set of DENSE images were acquired with temporal resolution adjusted to the new heart rate. The animal protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Case Western Reserve University.

MR Imaging

MRI experiments were performed on a 9.4T Bruker Biospec (Billerica, MA) horizontal bore scanner equipped with a gradient insert (950 mT/m, 20 cm inner diameter). A 3.6 cm quadrature volume coil (Rapid Biomedical, Rimpar, Germany) was used for image acquisition. A series of scout images were acquired to obtain the short-axis (SA) planes. After acquiring a horizontal long-axis (LA) image (four-chamber view), multi-phase DENSE SA images were prescribed at base and apex with 1 mm distance above and below the mid-ventricular level, respectively.

The multi-phase DENSE pulse sequence was developed based on SPAMM11 tagging (19). Following the tagging module, fast low angle single shot (FLASH) sequence with an additional unencoding gradient was repeated 14 times to encode displacement at 14 different cardiac phases (Fig. 1a). To correct for background phase errors mainly caused by B0 field inhomogeneity, a second set of DENSE images were acquired using displacement encoding/unencoding gradients with the same magnitude but opposite polarity as the first data set (23). Comparing to phase error correction using a phase reference image without displacement encoding, the subtraction of two scans with opposite displacement encoding gradients not only allowed correction for background phase errors, but also doubled the sensitivity of displacement encoding. Imaging parameters were: flip angle, 20°; TE, 2.3 ms; field of view, 3 cm × 3 cm; matrix size, 128×128; slice thickness, 1 mm; number of averages, 6. Displacement encoding frequency (k) was 1.11 cycles/mm. TR was adjusted according to the heart rate (HR) such that 14 images were acquired during one cardiac cycle for both baseline and dobutamine stimulation. To encode displacement in 2D plane, two sets of SA images were acquired with frequency and phase encoding directions swapped. Cine FLASH images were also acquired for the calculation of LV volumes and ejection fraction (EF).

Figure 1.

Multi-phase MR DENSE pulse sequence (a) and schematic data processing diagram (b). The positive and negative (dotted line) displacement encoding/unencoding gradients are implemented separately to generate two DENSE data sets. The subtraction of these two data sets eliminated systematic phase errors and doubled the sensitivity of displacement encoding.

Image Reconstruction and Analysis

Images were reconstructed offline using an in-house developed software package in Matlab (The Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA). LV contours were traced on cine FLASH images. LV volumes at end-diastole (ED), end-systole (ES), and ejection fraction were calculated accordingly. The myocardial segmentation was performed as previously described (24).

Displacement, Strain, and Torsion Quantification using Phase Unwrapping

To reconstruct the displacement field, a band-pass filter with a cut-off frequency of 0.90 cycles/mm in the read-out direction was used to eliminate the T1-relaxation echo and the residual complex conjugate echo (Fig. 1b). The filtered stimulated-echo was zero-filled to a 128×128 matrix in k-space. 2D Inverse Fourier Transform (2D-IFT) was then applied to generate the complex images. For a specific displacement encoding frequency, k, the phase-displacement relationship of the two images can be described as

and

where φ1 and φ2 are the phases from the two acquisitions with opposite displacement encoding gradients, respectively, φb is the background phase, and u is the displacement along the encoding direction. Therefore, the subtraction of these two phase images followed by phase unwrapping will allow the calculation of the displacement (25, 26)

| [1] |

where φ is the unwrapped phase computed from the subtraction of two oppositely encoded images. In the current study, phase unwrapping used an algorithm similar to the quality-guided path following method (22, 27). The 2D displacement map was then calculated from vector addition of two individual 1D maps, i.e., ux and uy. The Lagrangian strain tensor, E, was computed within each four-adjacent-pixel element from the 2D displacement using isoparametric formulation (28).

In addition to Lagrangian strains, ventricular twist and torsion were also quantified as described previously (24). Positive twist was defined as counterclockwise motion when viewed from the base of the heart. Torsion was then calculated as the difference in twist angles between apical and basal slices, normalized by the distance between the two slices.

Direct Strain Quantification using Spatial Phase Gradient

Alternatively, the 2D Lagrangian strain tensor can be calculated directly as

| [2] |

where F = I + ∇u is the 2D deformation gradient tensor, and I is the identity matrix. From Eq. 1, the displacement gradient tensor, ∇u, can be calculated as

| [3] |

In the current study, ∇φ was determined directly from the wrapped phase image, φ*, by eliminating the discontinuities in ∇φ* (7). Specifically, the discontinuities caused by wrapped phase were spatially shifted in the displacement encoding direction by taking the gradient of ∇(φ* + π) (Fig. 2g). By selecting the smaller magnitude between ∇φ* and ∇(φ* + π), we obtained a gradient tensor that was free of discontinuities and equivalent to ∇φ (Fig. 2h). Subsequently, the 2D Lagrangian strain tensor was calculated according to Eq. 2.

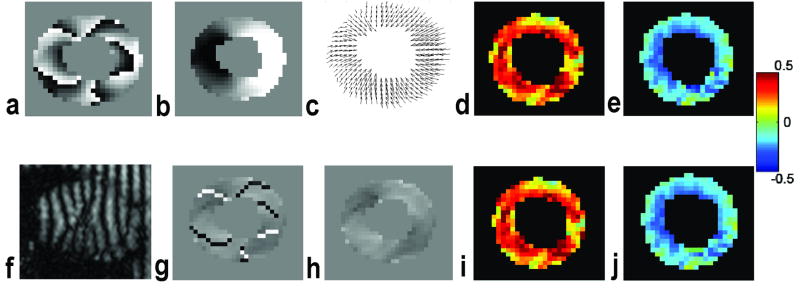

Figure 2.

Representative end-systolic DENSE images and the corresponding displacement and strain maps. a&b. original (a) and unwrapped (b) phase images with displacement encoding in the horizontal direction; c. 2D displacement field; d&e. radial and circumferential strain maps; f. magnitude image of the unfiltered image; g&h. phase gradient maps in the horizontal direction with (g) and without (h) discontinuity; i&j. radial and circumferential strain maps directly quantified from phase gradient maps.

The strain tensor was also transformed to a local myocardial coordinate system defined by the radial (r) and circumferential (c) directions (24), yielding two normal strains (Err, Ecc) represented by the diagonal elements in the transformed strain tensor, and the shear strain (Erc) from the off-diagonal elements.

Validation with MR Tagging

Tagged images were obtained from DENSE data by direct 2D Fourier Transform (2D-FT) without performing k-space filtering (Fig. 2f). For validation purpose, strain calculated by DENSE method was compared to those obtained from conventional MR tagging analysis. Multi-phase DENSE images were acquired from seven C57BL/6 mice at base, mid-ventricle, and apex with a 1.5 mm gap between adjacent slices. A k of 1.43 cycles/mm was used in validation study, yielding a tagging resolution of 0.7 mm. Strain analysis was performed on the tagged images using HARP and homogenous strain analysis method as previously described (29). With identical myocardial contours and segments, the strains and twist quantified by current method were compared to those calculated from tagging analysis. The correlation of the two methods was examined.

Statistics

All measurements are presented as mean ± SD. Comparisons between DENSE and tagging analysis were assessed using linear regression analysis and Bland–Altman plots. Myocardial strains in septal, anterior, lateral, and posterior segments, or at basal and apical levels, were compared separately by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). If there were statistical differences, multiple pairwise comparisons were performed using Tukey's test with a confidence interval of 95%. Heart rate, ejection fraction, myocardial strains and twist at baseline and under dobutamine stimulation were compared using paired student t-test. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Global Functional Indexes

Mean body temperature was 35.3 ± 0.4°C during MRI study. At baseline, mean heart rate was 470 ± 21 bpm. Under dobutamine stimulation, mean heart rate reached 541±13 bpm, which was a 15.0% increase over the basal heart rate (P<0.05). In addition, significant increase in ejection fraction was also observed under dobutamine stimulation (56.7 ± 2.0 % vs. 74.4 ± 1.8 %, P<0.05).

DENSE Image Analysis

Depending on the heart rate and respiratory pattern, a single multi-phase DENSE scan took 3-5 minutes to finish. The total post-processing time, including data loading, contour tracing, segmentation, and strain quantification, was about 30 minutes for a whole data set including both baseline and dobutamine stimulation. With a temporal resolution of <10 ms, we were able to examine the ventricular wall motion over the entire cardiac cycle. Representative DENSE reconstructed images (displacement and strain maps) at mid-ventricle are shown in Fig. 2. Transmural variation in myocardial strain is evident with higher strain values in the subendocardial region (Fig. 2d&e, i&j).

Validation with MR Tagging

Comparison of ventricular wall strain and twist quantified by the current DENSE method and those from traditional tagging analysis showed high correlation (R2>0.80) (Fig. 3a-c). In addition, Bland-Altman plots showed that strain quantified from DENSE and tagging methods were comparable, especially for circumferential strain and twist. The differences in circumferential strains and twists from the two methods were close to zero and most of the differences were within ±2SD (Fig. 3e&f). The quantification of radial strain by DENSE was slightly higher than that by tagging (Fig. 3d). Mean difference of radial strain quantified by DENSE and tagging was -0.04.

Figure 3.

Comparison of strain quantification by MR DENSE and MR tagging. a-c. Correlation between tagging and DENSE quantification of radial (a), circumferential strains (b), and ventricular twist (c); d-f. Bland–Altman plots of radial (d), circumferential strains (e), and ventricular twist (f) measured by tagging and DENSE. Strain calculation from DENSE images used direct strain quantification method.

Comparison of the Two Strain Quantification Methods

Comparison of ventricular wall strain quantified by the phase unwrapping method and direct strain quantification method also showed high correlation (R2>0.98) (Fig. 4a&b). In addition, Bland-Altman plots showed that strains quantified using these two methods were highly consistent (Fig. 4c&d). The mean differences in both radial and circumferential strains calculated from the two methods were zero and most of the differences were within ±2SD, which was <0.01.

Figure 4.

Comparison of strain calculation by phase unwrapping and direct strain quantification methods. a&b. Correlation between strain quantified by phase unwrapping and direct strain quantification on radial (a) and circumferential strains (b). c&d. Bland–Altman plots of radial (c) and circumferential strains (d), measured by phase unwrapping and direct strain quantification methods.

Baseline Strain and Twist

At baseline, peak systolic radial strain (Err) was 0.27 ± 0.02 and 0.21 ± 0.04 at apex and base, respectively. Peak systolic circumferential strain (Ecc) was -0.18 ± 0.01 and -0.15 ± 0.01 at the two levels, respectively (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Radial (a&b) and circumferential (c&d) strains at apex (a&c) and base (b&d). S, septum; P, posterior; L, lateral; A, anterior; Ave, slice average. White and black bars are strains at baseline and under dobutamine stimulation, respectively. *P<0.05 baseline versus dobutamine stimulation. #P<0.05 comparing with other segments. †P<0.05 comparing with the posterior and lateral segments. ‡P<0.05 comparing with the posterior. Strain calculation from DENSE images used direct strain quantification method.

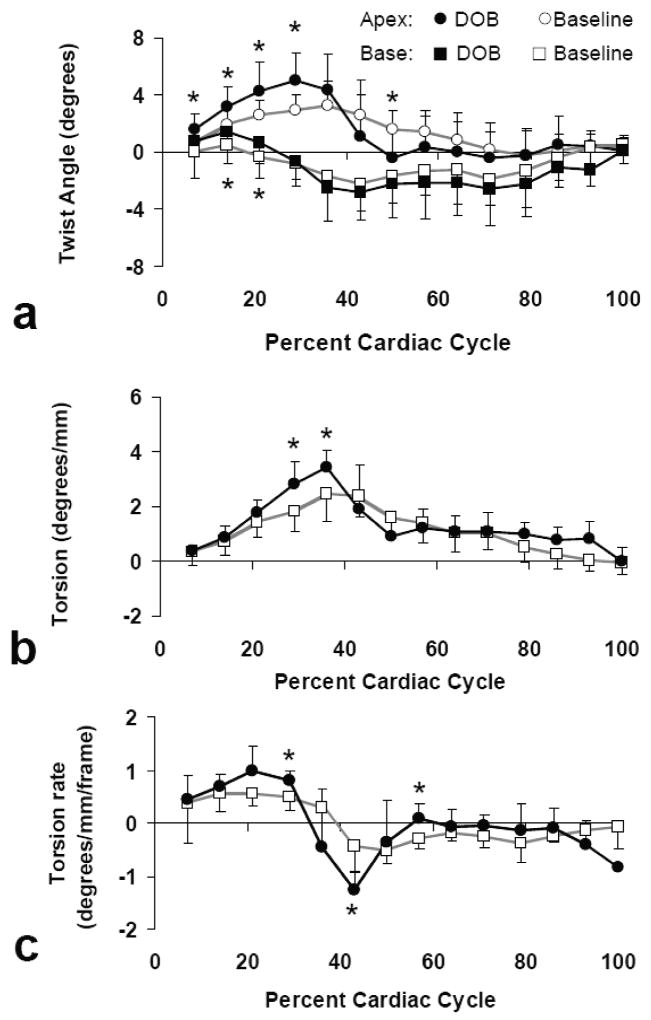

Consistent with previous finding in human hearts (30), counterclockwise twist was observed at base during early systole, which gradually shifted to clockwise twist later in the cardiac cycle (Fig. 6a). Peak systolic twist was -1.7 ± 1.2°, suggesting clockwise twisting at base. At apex, peak systolic twist was 3.3 ± 1.1°, indicating counterclockwise twist. This twisting pattern gave rise to a maximum torsion of 2.5 ± 0.5 °/mm at peak systole (Fig. 6b). The quantified strain and twist were similar to those reported in previous tagging (31) and DENSE (13) studies.

Figure 6.

Ventricular twist (a), torsion (b) and torsion rate (c) at baseline and under dobutamine stimulation. *P<0.05 baseline versus dobutamine stimulation.

Strain and Twist in Responses to Dobutamine Stimulation

Dobutamine stimulation induced a 17% increase in radial strain at apex and more than 20% increase in circumferential strain at both apex and base (P<0.05). With the exception of radial strain at base, the magnitude of anterior and lateral wall strain was increased by more than 20% in response to dobutamine stimulation at both levels (Fig. 5). Significant increase in septal Ecc was also observed at both apex and base (P<0.05, Fig. 5c&d).

During early systole, counterclockwise twist at both apex and base was enhanced by dobutamine stimulation (P<0.05, Fig. 6a). At peak-systole, β-stimulation induced a 53% increase in apical twist (P<0.05). As a result, a 37% increase of the peak-systolic torsion was observed when compared to baseline torsion (P<0.05) (Fig. 6b). Associated with the increase in torsion, peak systolic torsion rate was also significantly higher under β-stimulation. Additionally, dobutamine stimulation also induced a rapid untwisting at apex, which caused a faster decline of torsion during early diastole (Fig. 6a&c). Both torsion and torsion rate were similar to those at baseline during late diastole (Fig. 6b&c).

Discussion

In the current study, a 2D multi-phase MR DENSE imaging and analysis method was developed for direct quantification of myocardial wall strain. Using the proposed method, less than 10 ms temporal resolution and a nominal spatial resolution of 0.56 mm were achieved. A validation study that compared strain calculation by the current method and by MR tagging showed high correlation between the two methods (R2 > 0.80). Enhanced strain and torsion was quantified using the proposed method in dobutamine-stimulated mouse hearts.

Dobutamine stimulation, or stress test, has been used to identify myocardial dysfunction associated with abnormal contractile and perfusion reserves that may not manifest at rest. Previous studies have demonstrated the utility of MRI in evaluating the response to dobutamine stimulation by mouse hearts using either cine imaging (32) or MR tagging (14). Our current results of increased strain and torsion are consistent with these previous findings, suggesting that MR DENSE can also be used for stress test in mice with high temporal and spatial resolution. In addition, a rapid untwist was observed at apex during early diastole, which resulted in a significant increase in diastolic torsion rate in dobutamine-stimulated hearts (Fig. 6). The cause of this increased untwisting needs further investigation. It may result from the passive release of increased potential energy due to increased LV torsion during systole. This rapid recoil may serve as an important mechanism for efficient ventricular filling under β-adrenergic stimulation.

The chosen displacement encoding frequency of 1.11 cycles/mm and the use of displacement encoding gradients with opposite polarity lead to wrapped phase when myocardial displacement exceeds 0.23 mm. At peak systole, 1D displacement of myocardial tissue may exceed 0.6 mm, which causes the phase to wrap more than once. Therefore, a robust and accurate phase-unwrapping algorithm is critically important for accurate motion quantification by DENSE. Such methods may require sophisticated algorithms that use both spatial and temporal evolution of phase in multi-phase DENSE image analysis (22). Alternatively, one can unwrap the phase before data subtraction, which requires performing phase unwrapping on two individual data sets. In the current study, we used the spatial gradient of the wrapped phase images for direct Lagrangian strain quantification. By completely eliminating the phase unwrapping process, our current method permits automated strain computation that is free of user-dependent analytical errors. However, direct quantification of mayocardial displacement and ventricular twist is not feasible using this method.

In the current study, background phase errors were corrected by subtracting two DENSE images acquired with displacement encoding gradients of opposite polarities. This approach also allowed doubled sensitivity for displacement encoding as both images were displacement encoded but with opposite polarities. Previously, Kim et al. proposed a method of improved signal-to-noise ratio for DENSE MRI by combining a pair of spectrum peaks from the complex complementary spatial modulation of the magnetization (CSPAMM) images (25, 26). The DENSE images corresponding to these two spectrum peaks also have the same magnitude but opposite phase polarities, allowing doubled sensitivity for the calculated tissue displacement. Our current method is similar to that proposed by Kim et al. with no additional phase reference scan required to eliminate the background phase errors. However, our method requires k-space filtering, leading to reduced spatial resolution of the displacement and strain fields.

K-space filtering may also lead to errors in strain quantification due to incomplete filtering of the undesirable spectral peaks. In addition, the truncation of the stimulated peak also gives rise to Gibbs ringing. An alternative is to eliminate these unwanted spectral peaks during image acquisition using through-plane crusher gradients (11, 33). The major limitation of these methods was the signal loss associated with through-plane dephasing. The SNR efficiency, i.e., , was reduced by 10-20% with the use of crusher gradients in a multi-phase DENSE study of human hearts (34). Multi-acquisition methods such as complementary DENSE, CANSEL, and phase cycling were proposed to eliminate the unwanted spectral peaks in post-processing through algebraic manipulation of multiple acquisitions with different encoding patterns (19, 35, 36). These methods provided effective cancellation of artifact-generating peaks and also improved SNR by enabling the usage of smaller encoding frequencies. However, these multiple acquisition methods require prolonged imaging time and may subject to artifacts induced by physiological variations.

The current study was limited to 2D quantification of myocardial wall motion. To characterize 3D myocardial function, 3D tissue tracking techniques are needed (13, 21, 37, 38). However, most 3D motion tracking methods require prolonged image acquisition and/or sophisticated data analysis. On the other hand, our previous study that compared 2D and 3D tagging suggests that 2D tagging can yield similar measurements of radial and circumferential strains (24). The strong agreement between DENSE and tagging methods observed in the current study suggests that 2D multi-phase DENSE method can provide reliable quantification of ventricular deformation in the radial and circumferential directions. As radial and circumferential strains frequently will suffice to serve as sensitive indices of functional changes (14, 19, 39), multi-phase 2D DENSE method will provide a valuable tool for the quantification of regional myocardial wall motion with more efficient post-processing than tissue tagging.

Conclusion

In summary, the multi-phase MR DENSE imaging and analysis method developed in the current study allows direct cardiac strain quantification in mice at high spatial and temporal resolution. The utility of such method in delineating large changes in myocardial strain was demonstrated in mouse heart at both baseline and high workload induced by dobutamine stimulation. The proposed method permits comprehensive evaluation of mouse myocardial wall motion throughout the whole cardiac cycle with minimal user interference in image processing.

Acknowledgments

Grants: This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01 HL73315 and R01 HL86935 (X. Yu) and American Heart Association predoctoral fellowship 0615308B (J. Zhong).

References

- 1.James JF, Hewett TE, Robbins J. Cardiac physiology in transgenic mice. Circ Res. 1998;82:407–415. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zerhouni EA, Parish DM, Rogers WJ, Yang A, Shapiro EP. Human heart: tagging with MR imaging--a method for noninvasive assessment of myocardial motion. Radiology. 1988;169:59–63. doi: 10.1148/radiology.169.1.3420283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Axel L, Dougherty L. MR imaging of motion with spatial modulation of magnetization. Radiology. 1989;171:841–845. doi: 10.1148/radiology.171.3.2717762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Axel L, Dougherty L. Heart wall motion: improved method of spatial modulation of magnetization for MR imaging. Radiology. 1989;172:349–350. doi: 10.1148/radiology.172.2.2748813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou R, Pickup S, Glickson JD, Scott CH, Ferrari VA. Assessment of global and regional myocardial function in the mouse using cine and tagged MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:760–764. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osman NF, Kerwin WS, McVeigh ER, Prince JL. Cardiac motion tracking using CINE harmonic phase (HARP) magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:1048–1060. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199912)42:6<1048::aid-mrm9>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osman NF, McVeigh ER, Prince JL. Imaging heart motion using harmonic phase MRI. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2000;19:186–202. doi: 10.1109/42.845177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan L, Prince JL, Lima JA, Osman NF. Fast tracking of cardiac motion using 3D-HARP. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2005;52:1425–1435. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2005.851490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Streif JU, Herold V, Szimtenings M, Lanz TE, Nahrendorf M, Wiesmann F, Rommel E, Haase A. In vivo time-resolved quantitative motion mapping of the murine myocardium with phase contrast MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:315–321. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herold V, Morchel P, Faber C, Rommel E, Haase A, Jakob PM. In vivo quantitative three-dimensional motion mapping of the murine myocardium with PC-MRI at 17.6 T. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:1058–1064. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aletras AH, Ding S, Balaban RS, Wen H. DENSE: displacement encoding with stimulated echoes in cardiac functional MRI. J Magn Reson. 1999;137:247–252. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim D, Gilson WD, Kramer CM, Epstein FH. Myocardial tissue tracking with two-dimensional cine displacement-encoded MR imaging: development and initial evaluation. Radiology. 2004;230:862–871. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2303021213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilson WD, Yang Z, French BA, Epstein FH. Measurement of myocardial mechanics in mice before and after infarction using multislice displacement-encoded MRI with 3D motion encoding. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1491–H1497. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00632.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vandsburger MH, French BA, Helm PA, Roy RJ, Kramer CM, Young AA, Epstein FH. Multi-parameter in vivo cardiac magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates normal perfusion reserve despite severely attenuated beta-adrenergic functional response in neuronal nitric oxide synthase knockout mice. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2792–2798. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li W, Liu W, Zhong J, Yu X. Early manifestation of alteration in cardiac function in dystrophin deficient mdx mouse using 3D CMR tagging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2009;11:40–50. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-11-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epstein FH, Yang Z, Gilson WD, Berr SS, Kramer CM, French BA. MR tagging early after myocardial infarction in mice demonstrates contractile dysfunction in adjacent and remote regions. Magn Reson Med. 2002;48:399–403. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henson RE, Song SK, Pastorek JS, Ackerman JJ, Lorenz CH. Left ventricular torsion is equal in mice and humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H1117–H1123. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.4.H1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pelc NJ, Noll DC, Pauly J, inventors. Method of noninvasive myocardial motion analysis using bidirectional motion intergration in phase contrast MRI maps of myocardial velocity. USA patent 5257626. 1993

- 19.Gilson WD, Yang Z, French BA, Epstein FH. Complementary displacement-encoded MRI for contrast-enhanced infarct detection and quantification of myocardial function in mice. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51:744–752. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhong XD, Janiczek RL, French BA, Roy RJ, Kramer CM, Meyer CH, Epstein FH. Spiral cine DENSE MRI at 7T for quantification of regional function in the mouse heart [abstract] Proc. Proc ISMRM; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhong XD, French BA, Roy RJ, Meyer CH, Kramer CM, Epstein FH. Comprehensive assessment of myocardial strain in post-infarct mice using 3D cine DENSE. [abstract] J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2009;11(Suppl):149. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spottiswoode BS, Zhong X, Hess AT, Kramer CM, Meintjes EM, Mayosi BM, Epstein FH. Tracking myocardial motion from cine DENSE images using spatiotemporal phase unwrapping and temporal fitting. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2007;26:15–30. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2006.884215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhong X, Helm PA, Epstein FH. Balanced multipoint displacement encoding for DENSE MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61:981–988. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhong J, Liu W, Yu X. Characterization of three-dimensional myocardial deformation in the mouse heart: an MR tagging study. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;27:1263–1270. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim D, Epstein FH, Gilson WD, Axel L. Increasing the signal-to-noise ratio in DENSE MRI by combining displacement-encoded echoes. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:188–192. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim D, Kellman P. Improved cine displacement-encoded MRI using balanced steady-state free precession and time-adaptive sensitivity encoding parallel imaging at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2007;20:591–601. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghiglia DC, Pritt MD. Two-dimensional phase unwrapping: theory, algorithms, and software. Wiley Inter-Science; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moaveni S. Finite element analysis: theory and application with ANSYS. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu W, Chen J, Ji S, Allen JS, Bayly PV, Wickline SA, Yu X. Harmonic phase MR tagging for direct quantification of Lagrangian strain in rat hearts after myocardial infarction. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:1282–1290. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lorenz CH, Pastorek JS, Bundy JM. Delineation of normal human left ventricular twist throughout systole by tagged cine magnetic resonance imaging 1. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2000;2:97–108. doi: 10.3109/10976640009148678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu W, Ashford MW, Chen J, Watkins MP, Williams TA, Wickline SA, Yu X. MR tagging demonstrates quantitative differences in regional ventricular wall motion in mice, rats, and men. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H2515–H2521. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01016.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiesmann F, Ruff J, Engelhardt S, Hein L, Dienesch C, Leupold A, Illinger R, Frydrychowicz A, Hiller KH, Rommel E, Haase A, Lohse MJ, Neubauer S. Dobutamine-stress magnetic resonance microimaging in mice : acute changes of cardiac geometry and function in normal and failing murine hearts. Circ Res. 2001;88:563–569. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.6.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aletras AH, Balaban RS, Wen H. High-resolution strain analysis of the human heart with fast-DENSE. J Magn Reson. 1999;140:41–57. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhong X, Spottiswoode BS, Cowart EA, Gilson WD, Epstein FH. Selective suppression of artifact-generating echoes in cine DENSE using through-plane dephasing. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:1126–1131. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Epstein FH, Gilson WD. Displacement-encoded cardiac MRI using cosine and sine modulation to eliminate (CANSEL) artifact-generating echoes. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:774–781. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhong X, Spottiswoode BS, Cowart EA, Gilson WD, Epstein FH. Selective suppression of artifact-generating echoes in cine DENSE using through-plane dephasing. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:1126–1131. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilson WD, Yang Z, French BA, Epstein FH. Measurement of myocardial mechanics in mice before and after infarction using multislice displacement-encoded MRI with 3D motion encoding. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1491–H1497. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00632.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spottiswoode BS, Zhong X, Lorenz CH, Mayosi BM, Meintjes EM, Epstein FH. 3D myocardial tissue tracking with slice followed cine DENSE MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;27:1019–1027. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeyaraj D, Wilson LD, Zhong J, Flask C, Saffitz JE, Deschenes I, Yu X, Rosenbaum DS. Mechanoelectrical feedback as novel mechanism of cardiac electrical remodeling. Circulation. 2007;115:3145–3155. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.688317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]