Abstract

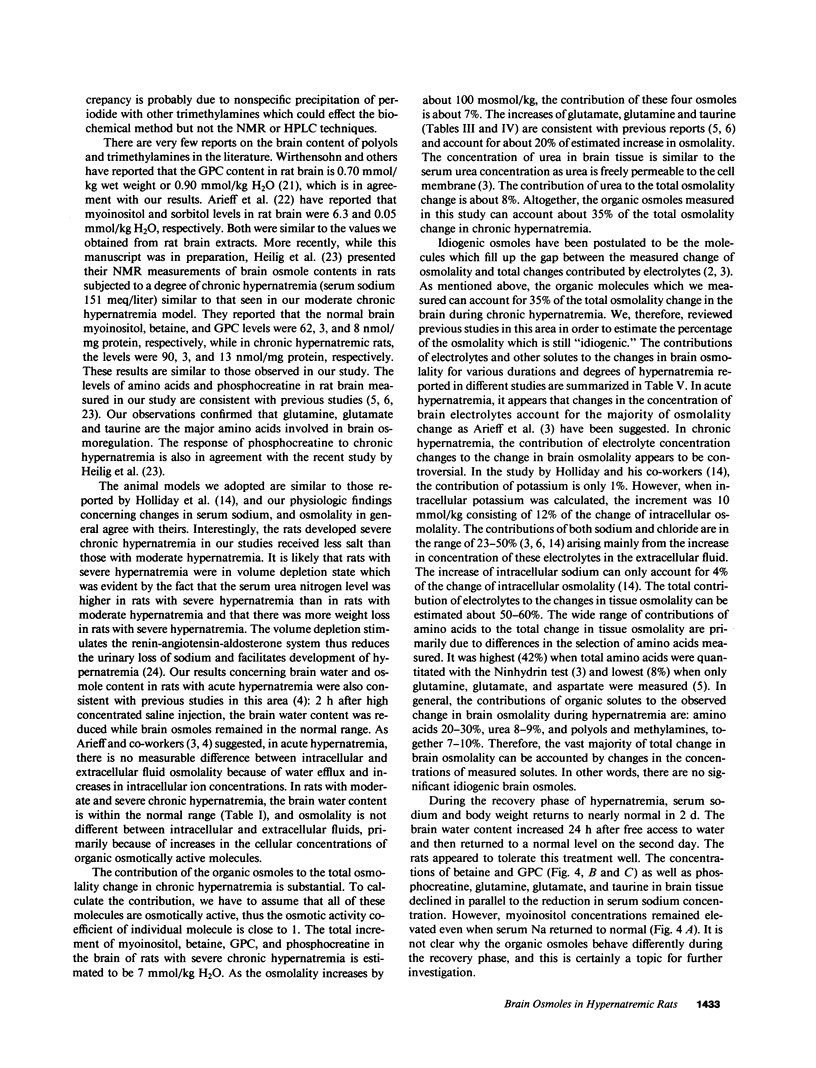

We studied the effects of varying degrees and durations of hypernatremia on the brain concentrations of organic compounds believed to be important, so-called "idiogenic" osmoles in rats by means of conventional biochemical assays, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, and high-performance liquid chromatography. There were no changes in the concentrations of these osmoles (specifically myoinositol, sorbitol, betaine, glycerophosphorylcholine [GPC], phosphocreatine, glutamine, glutamate, and taurine) in rats with acute (2 h) hypernatremia (serum Na 194 +/- 5 meq/liter). With severe (serum Na 180 +/- 4 meq/liter) chronic (7 d) hypernatremia, the concentrations of each of these osmoles except sorbitol increased significantly: myoinositol (65%), betaine (54%), GPC (132%), phosphocreatine (73%), glutamine (143%), glutamate (84%), taurine (78%), and urea (191%). Together, these changes account for 35% of the change in total brain osmolality. With moderate (serum Na 159 +/- 3 meq/liter) hypernatremia, more modest but significant increases in the concentrations of each of these osmoles except betaine and sorbitol were noted. When rats with severe chronic hypernatremia were allowed to drink water freely, their serum sodium as well as the brain concentrations of all of these organic osmoles except myoinositol returned to normal within 2 d. It is concluded that: idiogenic osmoles play an important role in osmoregulation in the brain of rats subjected to hypernatremia; the development of these substances occur more slowly than changes in serum sodium; and the decrease in concentration of myoinositol occurs significantly more slowly than the decrease in serum sodium which occurs when animals are allowed free access to water. These observations may be relevant to the clinical management of patients with hypernatremia.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Arieff A. I., Kleeman C. R. Studies on mechanisms of cerebral edema in diabetic comas. Effects of hyperglycemia and rapid lowering of plasma glucose in normal rabbits. J Clin Invest. 1973 Mar;52(3):571–583. doi: 10.1172/JCI107218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagnasco S., Balaban R., Fales H. M., Yang Y. M., Burg M. Predominant osmotically active organic solutes in rat and rabbit renal medullas. J Biol Chem. 1986 May 5;261(13):5872–5877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban R. S., Knepper M. A. Nitrogen-14 nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of mammalian tissues. Am J Physiol. 1983 Nov;245(5 Pt 1):C439–C444. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1983.245.5.C439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak A. J., Tuma D. J. Determination of choline, phosphorylcholine, and betaine. Methods Enzymol. 1981;72:287–292. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(81)72016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaine E. H., Davis J. O., Witty R. T. Renin release after hemorrhage and after suprarenal aortic constriction in dogs without sodium delivery to the macula densa. Circ Res. 1970 Dec;27(6):1081–1089. doi: 10.1161/01.res.27.6.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan P. H., Fishman R. A. Elevation of rat brain amino acids, ammonia and idiogenic osmoles induced by hyperosmolality. Brain Res. 1979 Feb 2;161(2):293–301. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finberg L. Hypernatremic (hypertonic) dehydration in infants. N Engl J Med. 1973 Jul 26;289(4):196–198. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197307262890407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullans S. R., Blumenfeld J. D., Balschi J. A., Kaleta M., Brenner R. M., Heilig C. W., Hebert S. C. Accumulation of major organic osmolytes in rat renal inner medulla in dehydration. Am J Physiol. 1988 Oct;255(4 Pt 2):F626–F634. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1988.255.4.F626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilig C. W., Stromski M. E., Blumenfeld J. D., Lee J. P., Gullans S. R. Characterization of the major brain osmolytes that accumulate in salt-loaded rats. Am J Physiol. 1989 Dec;257(6 Pt 2):F1108–F1116. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.257.6.F1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday M. A., Kalayci M. N., Harrah J. Factors that limit brain volume changes in response to acute and sustained hyper- and hyponatremia. J Clin Invest. 1968 Aug;47(8):1916–1928. doi: 10.1172/JCI105882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood A. H. Acute and chronic hyperosmolality. Effects on cerebral amino acids and energy metabolism. Arch Neurol. 1975 Jan;32(1):62–64. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1975.00490430084018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr J. W., McReynolds J., Grimaldi T., Acara M. Effect of acute and chronic hypernatremia on myoinositol and sorbitol concentration in rat brain and kidney. Life Sci. 1988;43(3):271–276. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(88)90317-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDOWELL M. E., WOLF A. V., STEER A. Osmotic volumes of distribution; idiogenic changes in osmotic pressure associated with administration of hypertonic solutions. Am J Physiol. 1955 Mar;180(3):545–558. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1955.180.3.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEHLING G., ULLRICH K. J. Uber das Vorkommen von Phosphorverbindungen in verschiedenen Nierenabschnitten und Anderungen ihrer Konzentration in Abhängigkeit vom Diuresezustand. Pflugers Arch. 1956;262(6):551–561. doi: 10.1007/BF00362117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock A. S., Arieff A. I. Abnormalities of cell volume regulation and their functional consequences. Am J Physiol. 1980 Sep;239(3):F195–F205. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1980.239.3.F195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somero G. N. Protons, osmolytes, and fitness of internal milieu for protein function. Am J Physiol. 1986 Aug;251(2 Pt 2):R197–R213. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1986.251.2.R197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama M., Itoh S., Nagasaki T., Tanimizu I. A new enzymatic method for determination of serum choline-containing phospholipids. Clin Chim Acta. 1977 Aug 15;79(1):93–98. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(77)90465-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurston J. H., Hauhart R. E., Dirgo J. A. Taurine: a role in osmotic regulation of mammalian brain and possible clinical significance. Life Sci. 1980 May 12;26(19):1561–1568. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(80)90358-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallenstein S., Zucker C. L., Fleiss J. L. Some statistical methods useful in circulation research. Circ Res. 1980 Jul;47(1):1–9. doi: 10.1161/01.res.47.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirthensohn G., Beck F. X., Guder W. G. Role and regulation of glycerophosphorylcholine in rat renal papilla. Pflugers Arch. 1987 Aug;409(4-5):411–415. doi: 10.1007/BF00583795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirthensohn G., Lefrank S., Schmolke M., Guder W. G. Regulation of organic osmolyte concentrations in tubules from rat renal inner medulla. Am J Physiol. 1989 Jan;256(1 Pt 2):F128–F135. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.256.1.F128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff S. D., Yancey P. H., Stanton T. S., Balaban R. S. A simple HPLC method for quantitating major organic solutes of renal medulla. Am J Physiol. 1989 May;256(5 Pt 2):F954–F956. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.256.5.F954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancey P. H., Clark M. E., Hand S. C., Bowlus R. D., Somero G. N. Living with water stress: evolution of osmolyte systems. Science. 1982 Sep 24;217(4566):1214–1222. doi: 10.1126/science.7112124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]