Abstract

Bas1p, a divergent yeast member of the Myb family of transcription factors, shares with the proteins of this family a highly conserved cysteine residue proposed to play a role in redox regulation. Substitutions of this residue in Bas1p (C153) allowed us to establish that, despite its very high conservation, it is not strictly required for Bas1p function: its substitution with a small hydrophobic residue led to a fully functional protein in vitro and in vivo. C153 was accessible to an alkylating agent in the free protein but was protected by prior exposure to DNA. The reactivity of cysteines in the first and third repeats was much lower than in the second repeat, suggesting a more accessible conformation of repeat 2. Proteolysis protection, fluorescence quenching and circular dichroism experiments further indicated that DNA binding induces structural changes making Bas1p less accessible to modifying agents. Altogether, our results strongly suggest that the second repeat of the DNA-binding domain of Bas1p behaves similarly to its Myb counterpart, i.e. a DNA-induced conformational change in the second repeat leads to formation of a full helix–turn–helix-related motif with the cysteine packed in the hydrophobic core of the repeat.

INTRODUCTION

The Myb transcription factor family contains numerous members from a wide spectrum of eukaryotic organisms as phylogenetically distant as yeast and human. All the members of the family are characterised by a conserved DNA-binding region located in the N-terminal part of the protein (1,2). This domain is composed of two or three imperfect tandem repeats containing highly conserved tryptophan residues. These repeats are predicted to form helix–turn–helix-related structures which are critical for DNA binding (3–5). Indeed, several mutations in these repeats have been obtained, in particular replacement of tryptophans (6,7) and of residues in the third ‘recognition helix’ in each repeat, and shown to affect DNA binding in vitro (3,4). A study of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae transcription factor Bas1p has revealed that mutations in the tryptophan residues strongly impair function of the protein both in vitro and in vivo (8). An interesting exception to this rule is the CDC5 subfamily, which contains the Cef1p protein from S.cerevisiae (9). Proteins from this subfamily are involved in pre-mRNA splicing and there is no clear evidence yet that they can act as transcription factors (10). Single mutations of the tryptophan residues in the first or second repeat of Cef1p did not affect function of the protein in vivo, while a combination of three or more of these mutations resulted in loss of function. Therefore, the conserved repeats are required for Cef1p function, but somewhat less stringently than in other Myb-like proteins which are known to bind DNA.

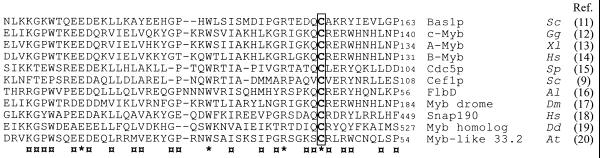

Besides the highly conserved tryptophan residues, it has been found that the Myb proteins carry in their second repeat a critical cysteine residue that is as conserved as the tryptophan residues (Fig. 1). Reduction of this residue is essential for c-Myb DNA binding in vitro (21–23) and it has been proposed to act as a molecular sensor making Myb function sensitive to redox conditions. A serine replacement of this cysteine in v-Myb neither transactivated transcription in vivo nor transformed myeloid cells, probably due to a defect in DNA binding (22). In contrast, its replacement by a hydrophobic residue allowed DNA binding in vitro and made the protein insensitive to SH-specific alkylating agents such as N-ethylmaleimide (23). This reactive residue has also been used to probe conformational changes in the second repeat and it was shown that, in the presence of the Myb DNA-binding site, the conserved cysteine became protected, probably due to a conformational change in the second repeat (23). The role of this residue was also evaluated in vivo in c-Myb and Cef1p by changing it to a serine. While this change affected Myb function in vivo (22), no effect was detected for Cef1p (9). To further evaluate the role of this highly conserved residue we have randomly mutated it in another yeast Myb-like protein named Bas1p.

Figure 1.

Optimal sequence alignment of the second repeat of the DNA-binding domain of Bas1p and repeats in other various Myb family members. Letters on the right refer to the species from which the sequences used for alignment were extracted. Sc, Saccharomyces cerevisiae; Gg, Gallus gallus; Xl, Xenopus laevis; Sp, Schizosaccharomyces pombe; Al, Aspergillus nidulans; Dm, Drosophila melanogaster; Hs, Homo sapiens; Dd, Dictyostelium discoideum; At, Arabidopsis thaliana. The identical and the highly conserved residues in all sequences aligned are marked by the symbols * and ¤, respectively. The conserved cysteine residue (C153 in Bas1p) is boxed. Numbers on the right refer to the position in the protein sequence.

Bas1p is a transcription factor, the binding site of which covers 8–9 bp, including the core consensus sequence 5′-TGACTC-3′, as judged by mutagenesis and by DNase I, missing base and DMS footprinting analyses (11,24,25). Together with the homeodomain protein Bas2p (Pho2p), Bas1p activates expression of genes in the histidine and purine biosynthesis pathways in response to exogenous adenine (24,26–28). In a gcn4 background, mutations that abolish BAS1 function lead to histidine auxotrophy and therefore BAS1 function can be easily scored in vivo (26). Furthermore, expression of the Bas1p target genes can be monitored, allowing a more quantitative estimation of Bas1p function. We took advantage of these properties to study in vivo the conserved cysteine in the Bas1p second repeat.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and media

Yeast strains used in this study were L3080 (MATa gcn4-2 ura3-52 bas1-2) and Y329 (MATa leu2-3,112 ura3-52 gcn4-2 bas1-2). Yeast were grown in SD (2% w/v glucose, 0.17% w/v nitrogen base and 0.5% w/v ammonium sulphate), SD-CASA (SD supplemented with 0.2% w/v casamino acids from Difco Laboratories) or SC [SD supplemented with amino acids as described by Sherman et al. (29)].

Oligonucleotides

The following oligonucleotides were used for BAS1 site-directed mutagenesis: 73, 5′-TGGAGGAACAGAGGATCAANNNGCGAAAAGGTACATTGAA-3′; 94, 5′-CCTGATTGGTGGAGGTGC-3′. For PCR amplification of the ADE5,7 probe used in electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) the following oligonucleotides were used: 125, 5′-CGCCCCGTCGGTAG-3′; 126, 5′-AGTTCAAGCCCATCGC-3′. The oligonucleotides used for radiolabelled ADE1 and ADE17 probes in northern blot experiments were: 36, 5′-CGCCCCGGGTTAGTGAGACCATTTAGA-3′; 41, 5′-CGCAGATCTTAATGTCAATTACGAAAGA-3′; 53, 5′-GCTGGTTGATGGAAAATA-3′; 54, 5′-TGCATGCACAGCAGGGTG-3′. Oligonucleotides used in protease treatment, fluorescence quenching and circular dichroism (CD) experiments were 5′-AGTGCCGACTGACTCGTGTCCTGG-3′ and 5′-CCAGGACACGAGTCAGTCGGCACT-3′ for the ADE5,7 specific probe and 5′-GCATTAATAACGGTTTTTTAGCGC-3′ and 5′-GCGCTAAAAAACGCTTATAATGC-3′ for the unrelated probe (MRE from Myrset et al.; 23).

Site-directed mutagenesis of BAS1

The plasmid used for Bas1p expression in yeast is termed P79. This centromeric plasmid carrying the URA3 and BAS1 genes was previously described (8). All the mutants described below were constructed in the P79 vector and were verified by sequencing. All the Bas1p C153 mutants were obtained by the gap repair method (30) as follows. Yeast strain L3080 was transformed with either plasmid P79 linearised with XhoI or plasmid P838 (31) linearised with BssHII and with a PCR fragment obtained using P79 as template with oligonucleotides 73 and 94 (oligonucleotide 73 contained a randomised sequence at the cysteine codon). C153K (P931) and C153D (P932) mutant plasmids were extracted by the method of Robzyk and Kassir (32) from yeast clones unable to grow on SC medium lacking uracil and histidine, whereas C153S (P925), C153A (P926) and C153V (P928) mutant plasmids were extracted from yeast clones able to grow on the same medium. The C82A (P1014), C206V (P1152), C82AC153V (P1067) and C82AC153VC206V (P1163) mutants were obtained as described (31). The remaining double mutants were obtained in two steps. First, the P1152 BamHI–XhoI fragment was replaced by the BamHI–XhoI fragment from pLU12 (33) to give plasmid P1154. The mutants C82AC206V and C153VC206V were then obtained by replacement of the P1154 BamHI–XhoI fragment by the BamHI–XhoI fragment from P1014 and P928, respectively. The resulting plasmids were named P1161 and P1158, respectively.

GST–HA–Bas1p fusion construction and purification

The plasmid used for the wild-type GST–HA–Bas1p fusion, termed P841, has been described previously (8). To facilitate construction of the various GST–HA–Bas1p mutants, a derivative plasmid of P841 containing a kanamycin resistance-conferring cassette was used (P870; 8). Plasmids carrying the various mutant versions of the GST–HA–Bas1p fusion for the C82A, C153R, C153D, C153K, C153S, C153A and C153V simple mutants and the C82AC153V double mutant were obtained by replacement of the BamHI–XhoI fragment of P870 by the BamHI–XhoI fragment from P1040, P838, P932, P931, P925, P926, P928 and P1089, respectively. The GST–HA–Bas1p fusion for the C206V simple mutant and the C82AC206V and C153VC206V double mutants were obtained by replacement of the BamHI–BbuI fragment of P870 by the BamHI–BbuI fragment from P1152, P1161 and P1158, respectively. The GST–HA–Bas1p fusion for the C82AC153VC206V triple mutant was constructed as described (31). All these GST–HA–Bas1p fusions were purified from Escherichia coli on glutathione–Sepharose 4B resin as described (8).

Expression and DNA binding analysis of c-Myb proteins

The minimal DNA-binding domain of the chicken c-Myb protein, R2R3, and its mutant derivatives (23) were expressed in E.coli using the T7 system (34) and proteins purified as described (4). DNA binding was monitored by EMSA as previously described (4), with the following modifications when performed at defined temperatures. After complex formation the binding reaction was loaded on a precast polyacrylamide gel (CleanGel; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) rehydrated in 0.5× TBE buffer and placed on a flatbed electrophoresis unit (Multiphore; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) equipped with a cooling plate connected to a thermostatic circulator (Multitemp III; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) which provided cooling water at defined temperatures. Electrophoretic separation was performed at 200 V for 135 min before the gel was exposed for autoradiography.

Protease treatment of Bas1p

Protease treatment was performed on a Bas1p fragment [containing the first 272 amino acid residues, designated NB1B2B3C55 in Høvring et al. (25)] using a derivative of the method used for c-Myb (23). Briefly, purified Bas1p protein (0.25 µg) was incubated in 10 µl of TEN buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl) with or without DNA (DNA:protein ratio 2:1 mol/mol) for 10 min at 37°C. Proteinase K (0.25–2.5 ng in 10 µl of TEN buffer) was added to the sample which was then incubated for a further 15 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by addition of SDS loading buffer and boiling for 2 min before loading on a 17.5% SDS–PAGE gel (35). Proteins were revealed by a silver staining procedure (36). In these experiments the specific DNA used was a double-stranded oligonucleotide corresponding to a sequence in the promoter of the ADE5,7 gene containing one Bas1p-binding site (37). The unrelated DNA used was the MRE (23), which does not bind Bas1p as determined by EMSA experiments (25).

Fluorescence spectroscopy

Fluorescence experiments were carried out as described for c-Myb (23) with purified Bas1p protein used at a concentration of 2 µM. The specific and unrelated DNAs used were the ADE5,7 and MRE double-stranded oligonucleotides described in the previous section.

Circular dichroism

CD spectra were recorded using a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter. Measurements were performed at 23°C, using a quartz cuvette with a path length of 0.1 cm and a protein concentration of 0.15 mg/ml in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer. Samples were scanned twice at 50 nm/min with a response time of 1 s and band width of 1 nm over the wavelength range 193–240 nm. The data were averaged and the spectrum of a protein-free control sample with or without DNA was subtracted. Thermal denaturation curves were determined by monitoring the change in the CD value at 222 nm with a temperature slope of 1°C/min. The α-helical content of Bas1p[1–272] was calculated after smoothing (means-movement, convolution width 5) from mean residual ellipticity at 222 nm ([θ]222) using the formula ¶H = [θ]222/[–40 000(1–2.5/n)], where ¶H and n represent the α-helical content and the number of peptide bonds, respectively (38).

Protein separation and detection

SDS–PAGE, western blot analyses and EMSAs were performed as previously described (8).

Northern blots

Yeast strain Y329 was transformed with either an empty plasmid as control (B836) or a plasmid carrying a wild-type (P79) or C153A mutant (P926) BAS1 gene. Cells were grown in SD-CASA to an OD600 of 0.5. RNA extraction, separation by electrophoresis, capillary transfer on positively charged nylon membrane, hybridisation and de-hybridisation were performed as previously described (28). Each blot was probed with a radiolabelled fragment specific for the gene studied. The probes used were as follows. For ADE1 and ADE17 specific probes were amplified by PCR using yeast genomic DNA as template and, respectively, the following pairs of synthetic oligonucleotides: 36 and 41 for ADE1, 55 and 56 for ADE17. For ACT1 the probe corresponds to the ClaI–ClaI internal fragment of the gene. Radiolabelling of the probes was done using the random priming procedure (Ready to go DNA labelling beads; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

β-Galactosidase (β-Gal) activity

For β-Gal assays Y329 cells were co-transformed with a plasmid carrying the lacZ fusion and either a centromeric plasmid carrying the BAS1 gene (wild-type or C153A mutant) or a corresponding centromeric empty plasmid. Six clones of each transformation were grown overnight in SC medium and then diluted at 0.1 OD600 in the same medium supplemented or not with 0.15 mM adenine. After 6 h at 30°C β-Gal assays were performed as described (8).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

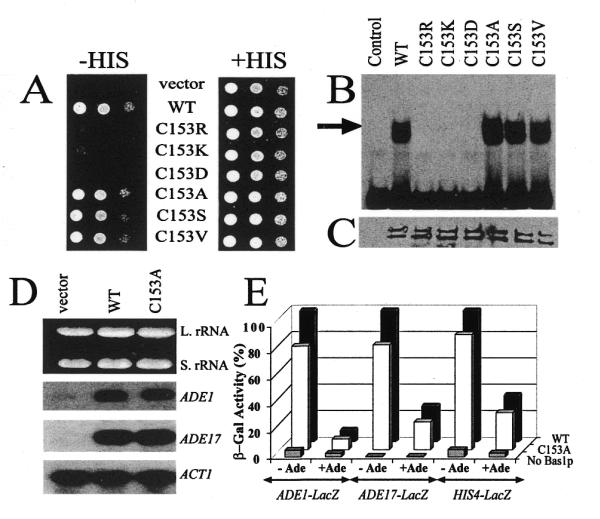

The conserved C153 residue can be changed to a hydrophobic residue without impairing Bas1p function in vivo and in vitro

Random mutagenesis of residue C153 in Bas1p, using gap repair in yeast (see Materials and Methods for experimental details), allowed us to isolate six mutants of C153. These mutants carried on a yeast expression vector were tested for their ability to complement a bas1 chromosomal deletion. As mentioned above, disruption of BAS1 in a gcn4 background leads to a strict histidine requirement, most probably because the HIS4 gene is not sufficiently expressed when these two transcription factors are absent (26). The results presented in Figure 2A show that three of the six mutations (the charged replacements C153R, C153K and C153D) totally abolished BAS1 function in vivo. The three remaining mutants (the neutral replacements C153A, C153S and C153V) fully complemented the bas1 disruption phenotype. The same six mutations were introduced in the BAS1 E.coli expression plasmid and purified mutant proteins were assayed for in vitro binding to DNA by EMSA (Fig. 2B). While similar amounts of mutant and wild-type proteins were used in this experiment (Fig. 2C), the three mutations that impaired complementation in vivo clearly abolished binding to DNA in vitro. Conversely, the three mutants that complemented the histidine auxotrophy bound DNA as efficiently as wild-type Bas1p. Finally, the effect of the C153A mutation on expression of Bas1p target genes was tested by northern blot on the ADE1 and ADE17 genes (Fig. 2D) and by measurement of expression of ADE1–lacZ, ADE17–lacZ and HIS4–lacZ fusions (Fig. 2E). Both approaches showed that the Bas1p C153A protein is fully functional in vivo. These data establish that the highly conserved C153 residue can be changed to small hydrophobic residues without affecting function of the transcription factor in vivo. Although our random mutagenesis of the C153 codon was not exhaustive, it is noteworthy that in the screening process we obtained three Cys→Ala, three Cys→Ser and four Cys→Val substitutions, therefore suggesting that most of the other substitutions might not lead to a functional transcription factor in vivo. It is intriguing that this cysteine is so highly conserved throughout evolution despite our demonstration here that several substitutions of the cysteine are fully functional.

Figure 2.

In vivo and in vitro effect of substitutions of the C153 residue of Bas1p. (A) In vivo effect of mutations in the C153 codon of BAS1. Y329 cells were transformed with either the B836 control plasmid (vector), the wild-type BAS1 gene (WT) or the various C153 substitution mutants. Transformants in exponential growth phase were resuspended in water. Three drops of cellular suspension corresponding to serial dilutions of the cells (104, 103 and 102 cells) were spotted on SC medium lacking uracil and supplemented (right) or not (left) with histidine. Cells were grown for 36 h at 30°C. (B) In vitro DNA-binding activity of Bas1p mutants. Purified GST–HA (control lane) or GST–HA–Bas1p wild-type (WT) or C153 mutants (0.5 µg each protein) were incubated for 15 min at room temperature with 100 fmol radiolabelled ADE5,7 promoter probe and were then separated by 4% non-denaturing gel electrophoresis. The gel was dried on paper and radioactivity was revealed by autoradiography. GST–HA–Bas1p/DNA complexes are indicated by the black arrow. (C) Western blot analysis of wild-type Bas1p and C153 mutants. Each purified GST–HA–Bas1p (4 µg each protein) was subjected to 12.5% SDS–PAGE and electroblotting on PVDF membrane. The blot was incubated with anti-HA antibodies (0.5 µg/ml) followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG (1:2500) as secondary antibodies and, finally, luminescent substrate before exposure to film. The GST–HA protein (25 kDa) in the control lane is much smaller than the GST–HA–Bas1p fusion (115 kDa) and therefore does not appear in the figure. (D) Effect of C153A substitution in Bas1p on ADE1 and ADE17 transcription. Strain Y329 was transformed with plasmids B836 (vector), P79 (WT, wild-type BAS1) or P926 (C153A mutant). Transformants were grown in SD-CASA to an OD600 of 0.5. Total RNA was extracted, separated by electrophoresis, transferred and hybridised with radiolabelled probes. Equal loading of each lane was monitored by ethidium bromide staining of the gel showing the large (L. rRNA) and small (S. rRNA) rRNAs and an ACT1-specific probe hybridisation. Each hybridisation was done independently and assembled for the figure. (E) In vivo effect of C153A substitution in Bas1p on expression of lacZ reporter fusions. Y329 cells were co-transformed with a plasmid containing the lacZ fusion and with a centromeric plasmid harboring the BAS1 wild-type or C153A mutant gene. –Ade and +Ade correspond to cells grown in the absence or presence of adenine, respectively. The control lane (No Bas1p) corresponds to a transformation with the B836 plasmid not containing the BAS1 gene. For each lacZ fusion β-Gal units are expressed as per cent expression measured in the absence of adenine with the wild-type (WT) BAS1 gene.

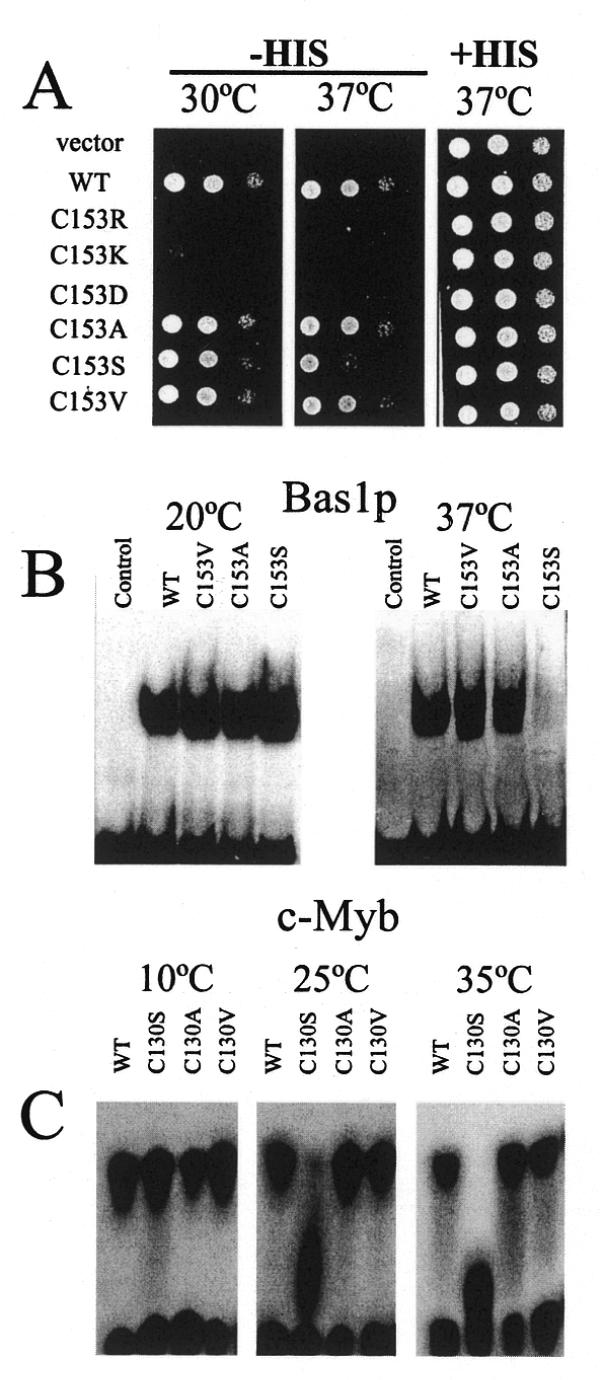

The corresponding cysteine residue in chicken c-Myb (C130) was previously shown by Gabrielsen and co-workers (23,39,40) to be in an unfolded region of the protein which, in the presence of DNA, undergoes a conformational change, folding into a ‘recognition’ helix with the cysteine moved into the hydrophobic core of the protein. Our substitution data on Bas1p C153 are consistent with a similar mechanism for Bas1p, since mutations that change C153 into a small hydrophobic residue did not affect Bas1p function (binding to DNA and activation of target genes) while replacing C153 by a charged residue totally abolished binding of Bas1p to DNA and its function in vivo. This strong structural and functional conservation between Bas1p and c-Myb was further validated by studying a specific feature of the Cys→Ser replacement in both proteins. We noticed that the C153S mutation in Bas1p led to only partial complementation of the histidine requirement at 37°C while complementation was total at 30°C (Fig. 3A). The other two changes (C153A and C153V) were functional at both temperatures. The same mutants and the wild-type protein were assayed for DNA binding in vitro. Once again, a clear correlation was found between DNA binding and complementation, i.e. the C153S mutant could only bind DNA at low temperature while the other proteins could bind DNA at both temperatures (Fig. 3B). Strikingly, the equivalent mutant (C130S) in c-Myb led to a very similar DNA-binding defect. The mutant was fully active at low temperature (10°C) but gradually lost DNA binding at higher temperatures (25 and 35°C; Fig. 3C). Although the precise temperature responses of the Cys→Ser mutants were slightly different, the similar ts phenotypes of Ser replacements in the two proteins further substantiates a strong structural and functional conservation between the c-Myb and Bas1p DNA-binding domains. The stronger temperature sensitivity of the c-Myb mutant may also explain why the C65S mutant of v-Myb was without transactivation and transformation activity at 37°C (22), while the C153S mutant of Bas1p was fully functional at 30°C.

Figure 3.

Temperature sensitivity of Cys→Ser replacement in the second repeat of the c-Myb and Bas1p DNA-binding domains. (A) In vivo effect of mutations in the C153 codon of BAS1 at 37°C. Y329 cells were transformed with either the B836 control plasmid (vector), the wild-type BAS1 gene or the various C153 substitution mutants and treated as in Figure 2A, but cells were grown at 37°C. The panel –His 30°C is a copy of the panel from Figure 2A added to facilitate a comparison of growth between the two temperatures tested. (B) In vitro DNA-binding activity of Bas1p mutants at different temperatures. Two microlitres (0.5 µg protein) of purified GST–HA (control lane) or GST–HA–Bas1p wild-type or C153 mutants were treated and analysed by EMSA as in Figure 2B at 20 and 37°C. (C) In vitro DNA binding activity of c-Myb mutants at different temperatures. Purified Myb R2R3 proteins (10 fmol both wild-type and mutants as indicated) were incubated with 10 fmol MRE probe at the indicated temperature for 10 min. The complex formed was separated by native electrophoresis using a thermostatic equipment set-up as described in Materials and Methods.

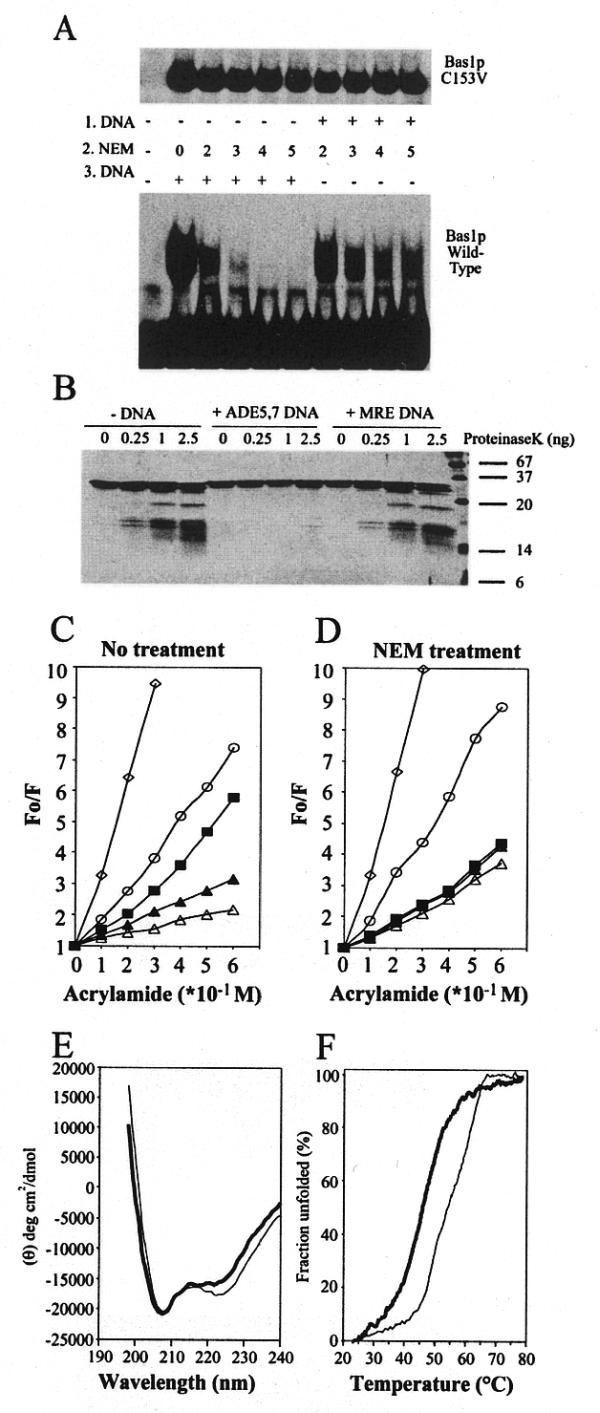

Binding to DNA induces a conformational change in Bas1p

The results obtained in the previous section suggest that the second repeat of the DNA-binding domain in Bas1p behaves as in c-Myb, with a conformational change occurring during DNA binding. To further support this hypothesis, we first used the irreversible SH-specific alkylating agent N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to test the effect of C153 modification on DNA-binding activity. Increasing concentrations of NEM were added to Bas1p in EMSA experiments. Wild-type Bas1p binding to the probe was abolished when 3 mM NEM was added to the protein prior to addition of the probe, while binding of the C153A (data not shown) and C153V (Fig. 4A) mutants was totally insensitive to the alkylating agent. These results show again that limited alterations are allowed in location of the C153 residue and suggest that, as shown for c-Myb, the irreversible modification of the C153 residue caused by NEM could interfere with the normal conformational change essential to acquire the DNA-binding structure in Bas1p. Consistent with this conformational hypothesis, addition of NEM to the preformed Bas1p–DNA complex resulted in a much greater resistance of the wild-type protein to the alkylating agent (Fig. 4A). This DNA-induced protection of Bas1p from alkylation is most easily explained by assuming a DNA-induced conformational change where C153 becomes inaccessible to the modifying agent. We reasoned that if this is correct, Bas1p should be in a more compact conformation when bound to DNA and then could be more resistant to limited proteolysis treatment. To directly test this, Bas1p, either free or complexed to DNA, was subjected to partial proteolysis with proteinase K (Fig. 4B). As expected, binding of Bas1p to a specific DNA probe resulted in an increased resistance of Bas1p to proteolysis. This resistance was not observed in the presence of an unrelated control DNA probe that gave a digestion pattern highly similar to that observed in the absence of DNA. These results strongly suggest that, as shown for c-Myb, Bas1p might adopt a much more structured conformation when bound to DNA. To further substantiate this hypothesis, the effect on Bas1p structure of binding to DNA was analysed by fluorescence quenching experiments. In these experiments the effect of conformational changes in Bas1p during DNA binding was monitored by measuring the accessibility of the tryptophan residues to acrylamide, a fluorescence quenching agent (Fig. 4C and D). The fluorescence quenching observed for native free Bas1p (Fig. 4C, closed square) was found to be significantly less than that observed for both guanidinium chloride-denatured Bas1p (Fig. 4C, open circle) or free tryptophan (Fig. 4C, open diamond), used here as a reference for free accessibility. Addition of the ADE5,7 specific DNA led to a further decrease in fluorescence quenching of Bas1p protein (Fig. 4C, open triangle), while addition of the same DNA had no significant effect on quenching of free tryptophan (data not shown). Finally, addition of an unrelated DNA (Fig. 4C, closed triangle) gave a quenching intermediate between those observed for free Bas1p and Bas1p complexed to the ADE5,7 probe. This intermediate behaviour could be due to non-specific binding of Bas1p to the unrelated DNA probe that would partially protect tryptophan residues against acrylamide, thus leading to an intermediate level of quenching. The same set of quenching experiments was done with Bas1p treated with NEM at 5 mM, a condition abolishing DNA binding (Fig. 4A). Under these conditions fluorescence quenching was the same both in the presence and absence of the specific DNA probe (Fig. 4D). Altogether, these results strongly support the idea of a DNA-induced conformational change in Bas1p. This was finally verified by CD analyses, showing that DNA binding was coupled to a structural change in Bas1p. CD spectra (Fig. 4E) of Bas1p[1–272] indicated typical α-helical characteristics similar to what has been reported for c-Myb R123 (41). Our finding of a 40% α-helical content in Bas1p and an increase to 45% when the protein is bound to specific DNA is also in good agreement with the results obtained for c-Myb (41). No change in mean residual ellipticity at 222 nm was observed upon complex formation with the unrelated DNA (MRE) and the α-helix content measured in this condition was 40% (spectrum not shown). Finally, Figure 4F shows the thermal denaturation of Bas1p[1–272] and Bas1p in complex with specific DNA measured by CD. It is clear from this experiment that the stability of the protein–DNA complex is higher compared to Bas1p alone. The melting temperature (Tm = temperature at 50% unfolding) was 54°C for Bas1p in complex with specific DNA, compared to 46°C obtained for Bas1p alone. This increased α-helical content and enhanced thermal stability strongly supports a structural change in Bas1p occurring during DNA binding, as previously described for the c-Myb oncoprotein.

Figure 4.

A DNA-induced conformational change in Bas1p. (A) Sensitivity of wild-type Bas1p and the C153A mutant to alkylation by NEM. (Lower) Two microlitres (0.5 µg protein) of purified wild-type GST–HA–Bas1p were incubated for 15 min at room temperature with increasing concentrations of NEM either before (1.DNA, left of pannel) or after (3.DNA, right) incubation with 100 fmol radiolabelled ADE5,7 promoter probe. Samples were then analysed by EMSA as in Figure 2B. (Upper) As above but carried out with the GST–HA–Bas1p C153V mutant. (B) Partial digestion of Bas1p, either free or complexed to DNA, with proteinase K. Bas1p[1–272] (0.25 µg) free (–DNA), in complex with ADE5,7 DNA (+ADE5,7 DNA) or in complex with unrelated DNA (+MRE DNA) was treated with increasing amounts of proteinase K. Proteins were then separated by 17.5% SDS–PAGE and revealed by silver staining. (C and D) Fluorescence quenching by acrylamide of free and DNA-bound Bas1p. The fluorescence emission of 2 µM Bas1p was quenched by successive addition of acrylamide to Bas1p treated (D) or not (C) with 5 mM NEM. In each condition fluorescence was measured at the wavelength corresponding to the emission maximum for Bas1p and the results are presented as the ratio between the unquenched fluorescence (Fo) and the fluorescence measured after acrylamide addition (F). Results correspond to the average of between six and nine independent measurements. Inter-assay variation was found to be <15 %. Closed square, Free Bas1p; open triangle, Bas1p bound to ADE5,7 specific DNA; closed triangle, Bas1p bound to unrelated DNA; open circle, Bas1p denatured for 60 min in 6 M guanidinium chloride; open diamond, 10 µM free tryptophan solution used as a reference. (E) CD spectrum of Bas1p[1–272] either alone (thick line) or in complex with specific DNA (ADE5,7 DNA, thin line). The protein concentration was 0.15 mg/ml in phosphate buffer and equimolar concentrations of DNA were added. The α-helical contents of Bas1p[1–272] alone and in complex with specific DNA were calculated as described in Materials and Methods and found to be 40 and 45%, respectively. (F) Thermal denaturation curves of Bas1p[1–272] either alone (thick line) or in complex with specific DNA (thin line). The apparent fraction of folded protein, obtained by monitoring the CD value at 222 nm, is shown as a function of temperature.

The C153 residue in the second repeat is the most accessible of the three cysteine residues in Bas1p, suggesting a conserved difference in thermal stability between the three repeats

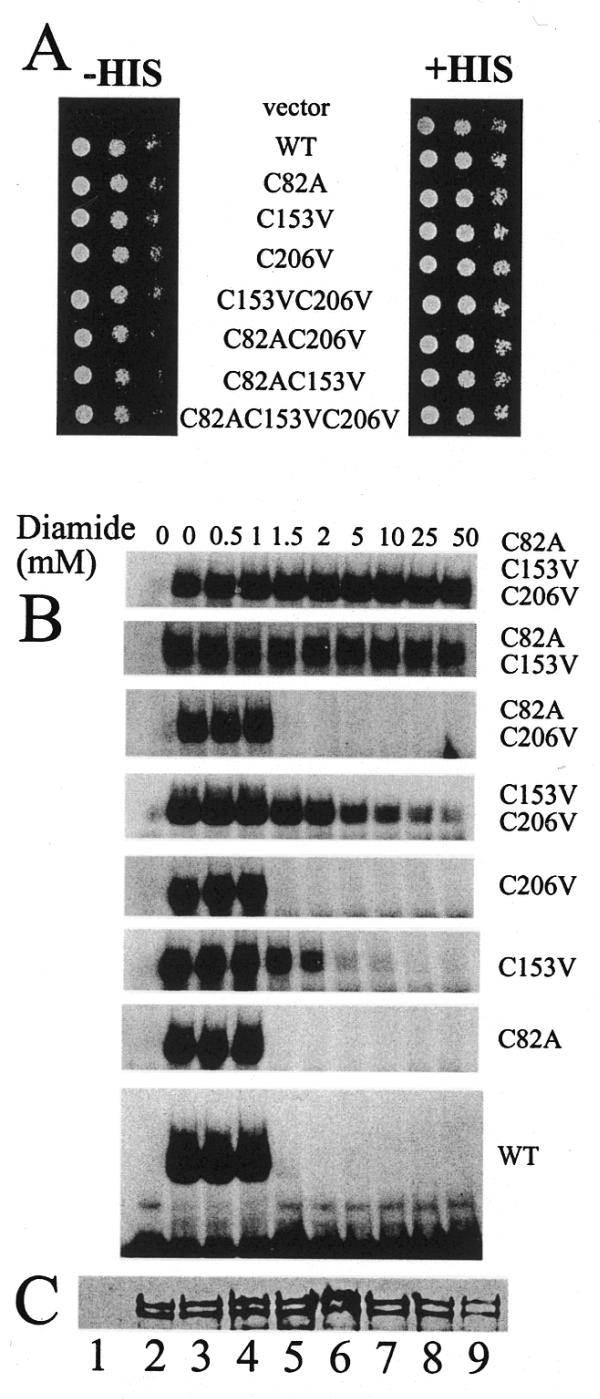

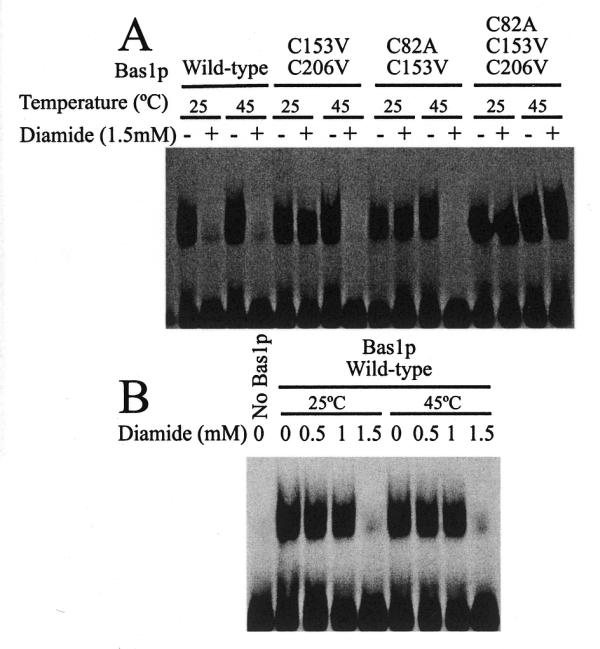

Although the three homologous tandem repeats in c-Myb have a high sequence similarity, they are not structurally equivalent. Biophysical studies have shown that the second repeat has a much lower thermal stability than the first and third repeats (42). To determine whether this structural feature is conserved during evolution, we took advantage of the specific cysteine distribution along the Bas1p protein, having one cysteine in each repeat of the Myb-like DNA-binding domain (8). We reasoned that the use of oxidative modification combined with systematic site-directed mutagenesis of these cysteine residues should provide information on the accessibility and structural stability of each of the repeats. First, the C82 and C206 residues, in the first and third repeats, respectively, were mutated in vitro. The resulting mutations were combined with the C153V mutation to generate all combinations of single, double and triple substitutions. These mutants were all shown to complement the bas1 disruption (Fig. 5A), suggesting that the cysteine residues in the first and third repeats are not essential for Bas1p function, as shown for the C153 residue in the second repeat in the previous sections. The corresponding purified GST–HA–Bas1p proteins were then assayed by EMSA for their ability to bind DNA in the presence of diamide, a thiol oxidising agent that can be used to probe the function of cysteine residues. The results presented in Figure 5B show that mutations C82A and C206V, either alone or combined, resulted in a wild-type sensitivity to diamide. C153V was partially resistant to diamide up to 2 mM. Interestingly, the C153V mutation combined with C82A or C206V showed some DNA binding at high concentrations of diamide (up to 50 mM) (Fig. 5B). Finally, the triple mutant was fully resistant to diamide, as expected if diamide treatment specifically affects cysteine residues. A western blot of the various mutant proteins (Fig. 5C) showed that similar amounts of proteins were used in this experiment. The results presented in Figure 5 were interpreted as follows: when the C153 residue is present, it confers on Bas1p wild-type sensitivity to diamide, while in the absence of C153 the two other cysteine residues confer a weak sensitivity to diamide. This reduced sensitivity to diamide treatment of the cysteine residues in the first and third repeats could be interpreted in different ways: (i) the cysteine residues are on the surface, but in an environment where bulky hydrophobic residues mask them from diamide treatment; (ii) the domains corresponding to the first and third repeats are in a more compact structure with the cysteine residues hidden in the hydrophobic core of the protein. In both cases the reduced sensitivity to diamide treatment could be explained by a reduced accessibility of the cysteine residues to the oxidative reagent. Thus a partial denaturation of Bas1p carrying only the C82 or C206 residues should lead to a sensitivity to diamide treatment equivalent to that of the wild-type protein. We therefore assayed the resistance of two double mutants carrying only C82 or C206 after preincubation with 2 mM diamide at 45°C (instead of 25°C as in previous assays) to partially denature Bas1p, as shown in Figure 4F. After oxidation the proteins were slowly brought back to room temperature and used for EMSA. The results presented in Figure 6A show that the two mutants were insensitive to diamide at 25°C (as previously shown in Fig. 5A) but their binding to DNA was totally abolished after preincubation with diamide at 45°C. The same proteins preincubated at 45°C in the absence of diamide were able to bind DNA normally, thus showing that the 45°C preincubation did not alter the capacity of Bas1p to bind DNA. As expected, the wild-type protein was sensitive to 2 mM diamide at both 25 and 45°C and the triple mutant was totally resistant under both temperature conditions (Fig. 6A). Finally, we show (Fig. 6B) that increasing the temperature has no effect on C153 oxidation, thus ruling out the possibility that diamide would be a more efficient oxidant at 45°C. These results show that the C153 residue in the second repeat is the most accessible of the three cysteine residues in Bas1p and further confirm a location of this residue in a more exposed region than the other two cysteine residues. This strongly suggests that the lowered thermal stability and the more open conformation of the second repeat described for c-Myb could be a feature of the Myb-type DNA-binding domain important enough to have been conserved during evolution from yeast to vertebrates. Taken together, all these results demonstrate a high structural and functional homology between the DNA-binding domain of both Bas1p and c-Myb oncoprotein.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the sensitivity to oxidation of the three cysteine residues in Bas1p. (A) In vivo effect of mutations of the three Cys residues in Bas1p. Y329 cells were transformed with either the B836 control plasmid (vector), the wild-type BAS1 gene or the various Cys substitution mutants and treated as in Figure 2A. (B) In vitro sensitivity to diamide of the different cysteine mutants of Bas1p. Purified wild-type GST–HA–Bas1p or cysteine mutants were incubated for 15 min at room temperature with increasing concentrations of diamide. Samples were then incubated with radiolabelled ADE5,7 promoter probe and analysed by EMSA as in Figure 2B. (C) Western blot analysis of purified wild-type and mutant GST–HA–Bas1p. Purified wild-type GST–HA–Bas1p and mutants fusions (10 µl) were separated by 12.5% SDS–PAGE and electrotransferred to PVDF membrane. GST–HA–Bas1p proteins were revealed by western blot analysis as in Figure 2C. Lane 1, GST–HA control; lanes 2–9, wild-type Bas1p and the C82A C153V C206V, C153V C206V, C82A C206V, C82A C153V, C206V, C153V and C82A Bas1p mutants, respectively.

Figure 6.

Effect of a partial denaturation on accessibility of the cysteine residues in Bas1p. (A) Effect of increased temperature on oxidation of C82 and C206 in Bas1p. Purified wild-type and mutant GST–HA–Bas1p proteins were incubated with or without 1.5 mM diamide at the indicated temperature (either 25 or 45°C) and immediately allowed to slowly return to room temperature. Samples were then incubated for 15 min with 100 fmol radiolabelled ADE5,7 promoter probe and analysed by EMSA as in Figure 2B. (B) Increased temperature has no major effect on diamide reactivity. Purified wild-type GST–HA–Bas1p was incubated with increasing concentrations of diamide at either 25 or 45°C and immediately allowed to slowly return to room temperature. Samples were then treated as in (A).

In conclusion, our study of the conserved C153 residue in the Bas1p DNA-binding domain shows that in this Myb-like transcription factor C153 is more accessible to oxidising and alkylating agents than the other two cysteines. This most probably reflects a conserved structural feature in the three tandem Myb repeats, with the second repeat being in a more open disordered conformation than the other two and undergoing a change to a more ordered conformation upon binding to DNA. Indeed, CD experiments show an increase in α-helical content from 40 to 45%, corresponding to the expected folding of one additional α-helix in B2, as previously stated for the c-Myb oncoprotein (41). Our data establish that, despite its very strong conservation during evolution, the cysteine residue in the second repeat of Myb proteins can be replaced by small hydrophobic amino acids without altering its function in vivo under laboratory conditions. This leads to the conclusion that a cysteine residue is not strictly required at this position in the sequence and raises the question of why this residue should be so highly conserved. We do not have any experimental evidence for a selective advantage due to the presence of the cysteine residue in repeat 2 of Bas1p, but sequence comparisons of Myb proteins strongly suggest that the presence of this residue conferring redox regulation is important under some physiological conditions that remain to be identified. We indeed observed redox regulation of expression of the Bas1p target genes (31) but a Bas1p mutant protein deprived of cysteine residues was unable to make transcription of these target genes resistant to oxidative stress (31). Another puzzling observation is the conservation of this cysteine residue among the CDC5 members of the Myb family (see Fig. 1; 9). These CDC5 proteins are known to be involved in pre-mRNA splicing and may not be transcription factors. If this were the case the role of this cysteine residue would not be restricted to DNA binding. This residue has been changed to a serine in Cef1p without any clear effect in vivo (9), again showing that a cysteine is not strictly required at this position.

Our results also point to very strong conservation between distant members of the Myb family, such as c-Myb and Bas1p. Although sequence homology between the two transcription factors is limited to the DNA-binding domain (11) and despite the fact that the two proteins bind to different DNA sequences, the mechanism of DNA binding appears highly conserved, involving a disorder-to-order transition in the second repeat moving the critical cysteine from an exposed to a hidden position in the protein. Our results thus validate the yeast transcription factor Bas1p as a model for the study of in vivo DNA binding of Myb-like proteins.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank F. Borne for help with mutant constructs and Dimitris Mantzilas and Anne Bostad Hegvold for their assistance with CD and one EMSA experiment, respectively. This work was supported by grants from the Conseil Régional d’Aquitaine, CNRS (UMR5095), The Norwegian Research Council, The Norwegian Cancer Society and the Anders Jahres Foundation. B.P. was supported by a FEBS post-doctoral long-term fellowship.

References

- 1.Ness S.A. (1996) The Myb oncoprotein: regulating a regulator. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1288, 123–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oh I.H. and Reddy,E.P. (1999) The myb gene family in cell growth, differentiation and apoptosis. Oncogene, 18, 3017–3033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frampton J., Gibson,T.J., Ness,S.A., Doderlein,G. and Graf,T. (1991) Proposed structure for the DNA-binding domain of the Myb oncoprotein based on model building and mutational analysis. Protein Eng., 4, 891–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gabrielsen O.S., Sentenac,A. and Fromageot,P. (1991) Specific DNA binding by c-Myb: evidence for a double helix-turn-helix-related motif. Science, 253, 1140–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogata K., Morikawa,S., Nakamura,H., Sekikawa,A., Inoue,T., Kanai,H., Sarai,A., Ishii,S. and Nishimura,Y. (1994) Solution structure of a specific DNA complex of the Myb DNA-binding domain with cooperative recognition helices. Cell, 79, 639–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saikumar P., Murali,R. and Reddy,E.P. (1990) Role of tryptophan repeats and flanking amino acids in Myb-DNA interactions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 8452–8456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanei-Ishii ,C., Sarai,A., Sawazaki,T., Nakagoshi,H., He,D.N., Ogata,K., Nishimura,Y. and Ishii,S. (1990) The tryptophan cluster: a hypothetical structure of the DNA-binding domain of the myb protooncogene product. J. Biol. Chem., 265, 19990–19995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinson B., Sagot,I., Borne,F., Gabrielsen,O.S. and Daignan-Fornier,B. (1998) Mutations in the yeast Myb-like protein Bas1p resulting in discrimination between promoters in vivo but not in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 3977–3985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohi R., Feoktistova,A., McCann,S., Valentine,V., Look,A.T., Lipsick,J.S. and Gould,K.L. (1998) Myb-related Schizosaccharomyces pombe cdc5p is structurally and functionally conserved in eukaryotes. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 4097–4108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burns C.G., Ohi,R., Krainer,A.R. and Gould,K.L. (1999) Evidence that Myb-related CDC5 proteins are required for pre-mRNA splicing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 13789–13794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tice-Baldwin K., Fink,G.R. and Arndt,K.T. (1989) BAS1 has a Myb motif and activates HIS4 transcription only in combination with BAS2. Science, 246, 931–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerondakis S. and Bishop,J.M. (1986) Structure of the protein encoded by the chicken proto-oncogene c-myb. Mol. Cell. Biol., 6, 3677–3684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sleeman J.P. (1993) Xenopus A-myb is expressed during early spermatogenesis. Oncogene, 8, 1931–1941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nomura N., Takahashi,M., Matsui,M., Ishii,S., Date,T., Sasamoto,S. and Ishizaki,R. (1988) Isolation of human cDNA clones of myb-related genes, A-myb and B-myb. Nucleic Acids Res., 16, 11075–11089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohi R., McCollum,D., Hirani,B., Den Haese,G.J., Zhang,X., Burke,J.D., Turner,K. and Gould,K.L. (1994) The Schizosaccharomyces pombe cdc5+ gene encodes an essential protein with homology to c-Myb. EMBO J., 13, 471–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wieser J. and Adams,T.H. (1995) flbD encodes a Myb-like DNA-binding protein that coordinates initiation of Aspergillus nidulans conidiophore development. Genes Dev., 9, 491–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters C.W., Sippel,A.E., Vingron,M. and Klempnauer,K.H. (1987) Drosophila and vertebrate myb proteins share two conserved regions, one of which functions as a DNA-binding domain. EMBO J., 6, 3085–3090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong M.W., Henry,R.W., Ma,B., Kobayashi,R., Klages,N., Matthias,P., Strubin,M. and Hernandez,N. (1998) The large subunit of basal transcription factor SNAPc is a Myb domain protein that interacts with Oct-1. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 368–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stober-Grasser U., Brydolf,B., Bin,X., Grasser,F., Firtel,R.A. and Lipsick,J.S. (1992) The Myb DNA-binding domain is highly conserved in Dictyostelium discoideum. Oncogene, 7, 589–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirik V. and Baumlein,H. (1996) A novel leaf-specific myb-related protein with a single binding repeat. Gene, 183, 109–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guehmann S., Vorbrueggen,G., Kalkbrenner,F. and Moelling,K. (1992) Reduction of a conserved Cys is essential for Myb DNA-binding. Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 2279–2286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grasser F.A., LaMontagne,K., Whittaker,L., Stohr,S. and Lipsick,J.S. (1992) A highly conserved cysteine in the v-Myb DNA-binding domain is essential for transformation and transcriptional trans-activation. Oncogene, 7, 1005–1009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myrset A.H., Bostad,A., Jamin,N., Lirsac,P.-N., Toma,F. and Gabrielsen,O.S. (1993) DNA and redox state induced conformational changes in the DNA-binding domain of the Myb oncoprotein. EMBO J., 12, 4625–4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daignan-Fornier B. and Fink,G.R. (1992) Coregulation of purine and histidine biosynthesis by the transcriptional activators BAS1 and BAS2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 6746–6750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Høvring P.I., Bostad,A., Ording,E., Myrset,A.H. and Gabrielsen,O.S. (1994) DNA-binding domain and recognition sequence of the yeast BAS1 protein, a divergent member of the Myb family of transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 17663–17669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arndt K.T., Styles,C. and Fink,G.R. (1987) Multiple global regulators control HIS4 transcription in yeast. Science, 237, 874–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Springer C., Künzler,M., Balmelli,T. and Braus,G.H. (1996) Amino acid and adenine cross-pathway regulation act through the same 5′-TGACTC-3′ motif in the yeast HIS7 promoter. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 29637–29643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denis V., Boucherie,H., Monribot,C. and Daignan-Fornier,B. (1998) Role of the myb-like protein Bas1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a proteome analysis. Mol. Microbiol., 30, 557–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sherman F., Fink,G.R. and Hicks,J.B. (1986) Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 30.Ma H., Kunes,S., Schatz,P. and Botstein,D. (1987) Plasmid construction by homologous recombination in yeast. Gene, 58, 201–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pinson B., Gabrielsen,O.S. and Daignan-Fornier,B. (2000) Redox regulation of AMP synthesis in yeast: a role of the Bas1p and Bas2p transcription factors. Mol. Microbiol., 36, 1460–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robzyk K. and Kassir,Y. (1992) A simple and highly efficient procedure for rescuing autonomous plasmids from yeast. Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 3790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cross F. (1997) ‘Marker swap’ plasmids: convenient tools for budding yeast molecular genetics. Yeast, 13, 647–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Studier F.W., Rosenberg,A.H., Dunn,J.J. and Dubendorff,J.W. (1990) Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol., 185, 60–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laemmli U.K. (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature, 227, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wray W., Boulikas,T., Wray,V.P. and Hancock,R. (1981) Silver staining of proteins in polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem., 118, 197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rolfes R.J., Zhang,F. and Hinnebusch,A.G. (1997) The transcriptional activators BAS1, BAS2 and ABF1 bind positive regulatory sites as the critical elements for adenine regulation of ADE5,7. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 13343–13354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scholtz J.M., Qian,H., York,E.J., Stewart,J.M. and Baldwin,R.L. (1991) Parameters of helix-coil transition theory for alanine-based peptides of varying chain lengths in water. Biopolymers, 31, 1463–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jamin N., Gabrielsen,O.S., Gilles,N., Lirsac,P.N. and Toma,F. (1993) Secondary structure of the DNA-binding domain of the c-Myb oncoprotein in solution. A multidimensional double and triple heteronuclear NMR study. Eur. J. Biochem., 216, 147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zargarian L., Le Tilly,V., Jamin,N., Chaffotte,A., Gabrielsen,O.S., Toma,F. and Alpert,B. (1999) Myb-DNA recognition: role of tryptophan residues and structural changes of the minimal DNA binding domain of c-Myb. Biochemistry, 38, 1921–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ebneth A., Schweers,O., Thole H., Fagin,U., Urbanke,C., Maass,G. and Wolfes,H. (1994) Biophysical characterization of the c-Myb DNA-binding domain. Biochemistry, 33, 14586–14593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sarai A., Uedaira,H., Morii,H., Yasukawa,T., Ogata,K., Nishimura,Y. and Ishii,S. (1993) Thermal stability of the DNA-binding domain of the Myb oncoprotein. Biochemistry, 32, 7759–7764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]