Abstract

The effects on the structural and functional properties of the Kv1.2 voltage-gated ion channel, caused by selective mutation of voltage sensor domain residues, have been investigated using classical molecular dynamics simulations. Following experiments that have identified mutations of voltage-gated ion channels involved in state-dependent omega currents, we observe for both the open and closed conformations of the Kv1.2 that specific mutations of S4 gating-charge residues destabilize the electrostatic network between helices of the voltage sensor domain, resulting in the formation of hydrophilic pathways linking the intra- and extracellular media. When such mutant channels are subject to transmembrane potentials, they conduct cations via these so-called “omega pores.” This study provides therefore further insight into the molecular mechanisms that lead to omega currents, which have been linked to certain channelopathies.

Mutations of the gating charge residues (GQRs) in genes coding for K+, Na+, or Ca2+ voltage-gated ion channels (VGCs) have been shown to impair cellular function and have been linked to certain inherited channelopathies, e.g., epilepsy, long QT syndrome, and paralyses (1) (see the Supporting Material). These mutations modify the physical properties of VGCs, e.g., sensitivity to voltage changes, which alters conduction through the central (alpha) pore (2–4). Specific mutations may, however, lead to the appearance of another current component aside from the alpha conduction (5). This so-called “omega” or gating-pore current was attributed to leakage of cations through a conduction pathway within the voltage sensor domain (VSD). In Na+ VGCs (6), such currents were correlated with mutations that cause normo- and hypokalemic periodic paralysis (7–9).

Here, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are used to investigate the effect of selected mutations of the GQRs on the stability and conduction properties of the Kv1.2 VGC embedded in a POPC lipid bilayer and a 150 mM of KCl salt solution. Two key conformations of the channel have been considered: one corresponds to the x-ray crystal structure of the open channel (10,11), whereas for the second, we used a channel model in which the VSD has the conformation of the closed state. The latter was built starting from the Kv1.2 open conformation, the configuration of its VSD being generated by dragging S4 downwards using harmonic constraints (see the Supporting Material). To evaluate the conformation, two tests were carried out:

-

1.

Comparison of VSD interresidues distances probed by experiments and those extracted from the MD simulations.

-

2.

Measurement of the total gating charge: 13e here, in agreement with the 12–14e measured (12,13).

The final model also compares well with other models recently proposed (14,15), except for the position of the S4 helix, for which the GQRs are shifted further down (closed-state PDB file provided in the Supporting Material).

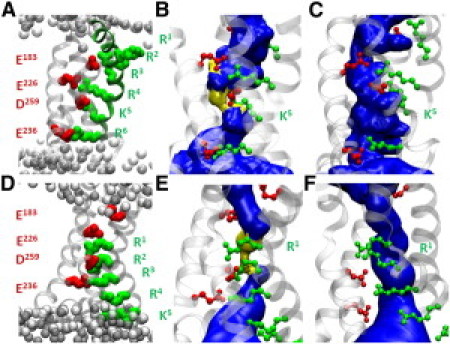

In Kv1.2, each S4 segment carries six GQRs: R1–R4, K5, and R6 involved in a state-dependent salt-bridges' network. MD simulations (No. 0, No. 11; see Table 1) of the open and closed conformations of Kv1.2 showed that the structures of the VSDs remain stable. In the open conformation (Fig. 1 A), the top residues R1 and R2 are located at the membrane-water interface and interact with lipid PO4– groups and R3 is close to E183 (S1). Deeper, R4, K5, and R6 are respectively involved in salt bridges with E226(S2), D259(S3), and E236(S2) in good agreement with experiments (16–18) and with previous simulations (11,19–22). In the closed-state model (Fig. 1 D), R1 interacts with both E226 and D259; R2 lies between D259 and E236 and R3 is a little below E236 (5). R4, K5, and R6, interact with the lipid PO4– groups. In both conformations, the VSD topology delimits an hourglasslike structure in which water penetrates from the extra- and the intracellular sides. In agreement with previous investigations (6,23,24), salt bridges involving lower residues in the open and upper ones in the closed conformation participate in the constrictions that prevent communication between the lower and the upper water crevices (Fig. 1, B and E).

Table 1.

Summary of all MD simulations

| No. | State | Channel mutations | Voltage∗ | Time (ns) | Omega pore† | Leak‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0/5 | Open | WT | No/Yes | 50/60 | — | — |

| 1/6 | R1 and R2 | No/Yes | 20/60 | — | — | |

| 2/7 | R3 and R4 | No/Yes | 40/40 | — | — | |

| 3/8 | K5 and R6 | No/Yes | 40/150 | Yes | Yes | |

| 4/10 | K5 | No/Yes | 60/100 | Yes | ?§ | |

| 11/14 | Closed | WT | No/Yes | 100/40 | — | — |

| 12/15 | R1 | No/Yes | 10/40 | Yes | Yes | |

| 13/16 | R2 | No/Yes | 10/40 | — | — |

Applied voltage is 0.6 V for the open state and −0.6 V for the closed one.

At equilibrium.

Under transmembrane voltage conditions.

Partial conduction (see the Supporting Material).

Figure 1.

VSD Topologies of the open (top panels) and closed (lower panels) Kv1.2 channel conformations. (A and D) Location of the S4 GQRs (green) and the salt bridges they form with basic charges (red). (B and E) Solvent-accessible volume (blue) within the VSD of the WT channels, for which the most constricted regions (pore radius <1.15 Å) are depicted in yellow. (C and F) K5 and R1 respective mutants, in which omega pores are formed.

Then, MD simulations of the open channel conformation were performed, in which selected S4 GQRs were substituted by uncharged counterparts, thereby mimicking their mutations to glutamine (see Table 1). All the VSD domains but those of the K5/R6 double-mutant remained stable (see the Supporting Material). During simulation No. 3, indeed, the K5-D259 and R6-E236 electrostatic interactions were disrupted, and, within 1 ns, the distance between their moieties increased from ∼3 Å to ∼8 Å. As a result, the VSD adopted a swollen-stable structure in which a connected hydrated pathway (omega pore) opened up between the intra- and extracellular media. Simulation No. 4 indicated that the single mutation of K5 is enough to destabilize the VSD in a similar manner (Fig. 1 C). For the closed-state conformation, the constriction in the VSD involves R1 and R2. Accordingly, we studied only the R1 and R2 mutants (simulations No. 12 and 13). Only the mutation of R1 led to breaking of the salt bridges and formation of an omega pore (Fig. 1 F) in agreement with Gamal El-Din et al. (25).

The conducting properties of the omega pores have been investigated by submitting the systems to TM potentials. Explicit ion dynamics has been employed (21,26), with applied voltages six times' larger than under physiological conditions (±600 mV), to enhance the ionic conduction and, in order to prevent the alpha pore conduction, the motion of the selectivity filter residues was restrained. As expected, both the WT channels and mutants in which the VSD constriction was preserved (simulations No. 5, 6, 7, 14, and 16) displayed no conduction over the timescales explored. Even under such high TM voltages, in each of the simulations carried out, the VSDs remained very stable, maintaining the specific constriction. In contrast, two of the three mutants where omega pores formed under equilibrium conditions were permeable to K+ ions (simulations No. 8 and 15). Due to the neutralization of the GQRs, the omega pores display an excess of basic residues. Accordingly, no conduction of Cl− ions was witnessed in agreement with experiments (5) and the K+ conduction through the VSD was mainly stochastic due to intermittent binding of these cations to the omega pore lining negative charges. Interestingly, in agreement with a recent investigation of the Shaker Kv channel (25), within the same time lapse, the K5 single mutant (simulation No. 10) displayed only partial translocation of a cation through the omega pore, with no subsequent complete ionic transport (see the Supporting Material).

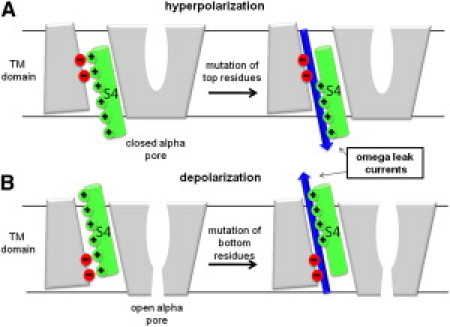

The results obtained above may be summarized as follows (Fig. 2): At rest, VGCs are in a closed nonconducting conformation and S4 is in the so-called “down” state. Within the VSD, the salt bridges that maintain the constriction between the intra- and extracellular water crevices involve top S4 GQRs and only their mutation leads to omega currents (Fig. 2 A). Upon activation, i.e., under depolarized TM potentials, the GQRs are dragged upwards (S4 moves to the up-state) and the VGCs adopt the open conformation. Within the VSD, bottom S4 GQRs become critical in maintaining the constriction (5,23). Accordingly, mutations of the latter destabilize the VSDs and lead to omega currents (Fig. 2 B). Hence, mutations of the S4 GQRs give rise to state-dependent omega currents. These results are consistent with experiments showing that 1), mutations (synthetic or genetic) of the S4 top GQRs of the Na+ VGCs Nav1.2a (6) and Nav1.4 (7) and of Shaker channels (5) lead to inward omega currents under hyperpolarized potentials; and 2), mutations of the S4 bottom GQRs of Nav1.2a (6) and Nav1.4 (9) lead to outward omega currents under depolarized potentials.

Figure 2.

(A) Under hyperpolarized potentials, the VGC is closed. Omega currents represent an inward cation leak (blue arrow). (B) Under depolarized potentials, the channel is open. Omega outward currents are a modulation of the alpha (central pore) current.

In summary, the present work has identified molecular details of omega conduction, complementing experimental data by revealing the distortion of the VSD structure when a mutation occurs. Note that the mutations considered here involved neutralization of the GQRs. The results summarized in Fig. 2 remain, however, relevant because experiments indicate that mutation of the GQRs to any neutral residue has similar consequences on the VGC (the Supporting Material).

Under hyperpolarized TM potentials, omega currents affect directly the channels function because they constitute a leak through a supposedly closed channel. Quite interestingly, most mutations associated with genetic diseases fall in this category. Under depolarized TM potentials, VGCs are open and omega currents are a modulation of the alpha current (the omega pore conductance is ∼2 orders of magnitude lower than the alpha pore conductance (6,7,9) (see the Supporting Material). Such small conductance must, however, have a more dramatic consequence on VGCs that undergo inactivation, i.e., become nonconductive under extended depolarized voltages, as shown for Nav1.4, for which omega leak currents were implicated in NormoPP symptoms (9).

Owing to the structural similarity between the members of the large family of VGCs (Nav, Cav, and Kv), mutations of key VSD GQRs are expected to result in similar effects to those characterized here for Kv1.2. However, precise knowledge of 1), the salt bridges network, and 2), the specific GQRs involved in the VSD constriction (and hence an accurate model of the third-dimensional structure) would be necessary to determine which specific mutation detected in a given channelopathy gives rise to omega currents.

Acknowledgments

This work was performed using HPC resources from GENCI-CINES (grant No. 2009-075137). M.L.K. thanks the National Institutes for Health for support under grant No. GM 40712 and W.T. thanks the National Council of Technological and Scientific Development for support under grant No. 471590/2009-6.

Supporting Material

References and Footnotes

- 1.Lehmann-Horn F., Jurkat-Rott K. Voltage-gated ion channels and hereditary disease. Physiol. Rev. 1999;79:1317–1372. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bao H., Hakeem A., Rayner M.D. Voltage-insensitive gating after charge-neutralizing mutations in the S4 segment of Shaker channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 1999;113:139–151. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jurkat-Rott K., Mitrovic N., Lehmann-Horn F. Voltage-sensor sodium channel mutations cause hypokalemic periodic paralysis type 2 by enhanced inactivation and reduced current. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:9549–9554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soldovieri M.V., Miceli F., Taglialatela M. Correlating the clinical and genetic features of benign familial neonatal seizures (BFNS) with the functional consequences of underlying mutations. Channels (Austin) 2007;1:228–233. doi: 10.4161/chan.4823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tombola F., Pathak M.M., Isacoff E.Y. Voltage-sensing arginines in a potassium channel permeate and occlude cation-selective pores. Neuron. 2005;45:379–388. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sokolov S., Scheuer T., Catterall W.A. Ion permeation through a voltage- sensitive gating pore in brain sodium channels having voltage sensor mutations. Neuron. 2005;47:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sokolov S., Scheuer T., Catterall W.A. Gating pore current in an inherited ion channelopathy. Nature. 2007;446:76–78. doi: 10.1038/nature05598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Struyk A.F., Cannon S.C. A Na+ channel mutation linked to hypokalemic periodic paralysis exposes a proton-selective gating pore. J. Gen. Physiol. 2007;130:11–20. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sokolov S., Scheuer T., Catterall W.A. Depolarization-activated gating pore current conducted by mutant sodium channels in potassium-sensitive normokalemic periodic paralysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:19980–19985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810562105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Long S.B., Campbell E.B., Mackinnon R. Crystal structure of a mammalian voltage-dependent Shaker family K+ channel. Science. 2005;309:897–903. doi: 10.1126/science.1116269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Treptow W., Tarek M. Environment of the gating charges in the Kv1.2 Shaker potassium channel. Biophys. J. 2006;90:L64–L66. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.080754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schoppa N.E., McCormack K., Sigworth F.J. The size of gating charge in wild-type and mutant Shaker potassium channels. Science. 1992;255:1712–1715. doi: 10.1126/science.1553560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seoh S.A., Sigg D., Bezanilla F. Voltage-sensing residues in the S2 and S4 segments of the Shaker K+ channel. Neuron. 1996;16:1159–1167. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pathak M.M., Yarov-Yarovoy V., Isacoff E.Y. Closing in on the resting state of the Shaker K+ channel. Neuron. 2007;56:124–140. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khalili-Araghi F., Jogini V., Schulten K. Calculation of the gating charge for the Kv1.2 voltage activated potassium channel. Biophys. J. 2010;98:2189–2198. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.02.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papazian D.M., Shao X.M., Wainstock D.H. Electrostatic interactions of S4 voltage sensor in Shaker K+ channel. Neuron. 1995;14:1293–1301. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tiwari-Woodruff S.K., Schulteis C.T., Papazian D.M. Electrostatic interactions between transmembrane segments mediate folding of Shaker K+ channel subunits. Biophys. J. 1997;72:1489–1500. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78797-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campos F.V., Chanda B., Bezanilla F. Two atomic constraints unambiguously position the S4 segment relative to S1 and S2 segments in the closed state of Shaker K channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:7904–7909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702638104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jogini V., Roux B. Dynamics of the Kv1.2 voltage-gated K+ channel in a membrane environment. Biophys. J. 2007;93:3070–3082. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.112540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishizawa M., Nishizawa K. Molecular dynamics simulation of Kv channel voltage sensor helix in a lipid membrane with applied electric field. Biophys. J. 2008;95:1729–1744. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.130658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Treptow W., Tarek M., Klein M.L. Initial response of the potassium channel voltage sensor to a transmembrane potential. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:2107–2109. doi: 10.1021/ja807330g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bjelkmar P., Niemelä P.S., Lindahl E. Conformational changes and slow dynamics through microsecond polarized atomistic molecular simulation of an integral Kv1.2 ion channel. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2009;5:e1000289. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krepkiy D., Mihailescu M., Swartz K.J. Structure and hydration of membrane embedded with voltage-sensing domains. Nature. 2009;462:473–479. doi: 10.1038/nature08542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bezanilla F. The voltage-sensor structure in a voltage-gated channel. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005;30:166–168. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gamal El-Din T., Heldstab H., Greef N.G. Double gaps along Shaker S4 demonstrates omega currents at three different closed states. Channels. 2010;4:75–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delemotte L., Dehez F., Tarek M. Modeling membranes under a transmembrane potential. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:5547–5550. doi: 10.1021/jp710846y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.