Abstract

Synovial fibroblasts destroy articular cartilage and bone in rheumatoid arthritis, but the mechanism of fibroblast transformation remains elusive. Because gain-of-function mutations of BRAF can transform fibroblasts, we examined BRAF in rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts. The strong gain-of-function mutation, V600R, of BRAF found in melanomas and other cancers was identified in first passage synovial fibroblasts from two of nine rheumatoid arthritis patients and confirmed by restriction site mapping. BRAF-specific siRNA inhibited proliferation of synovial fibroblasts with V600R mutations. A BRAF aberrant splice variant with an intact kinase domain and partial loss of the N-terminal autoinhibitory domain was identified in fibroblasts from an additional patient, and fibroblast proliferation was inhibited by BRAF-specific siRNA. Our finding is the first to establish mechanisms for fibroblast transformation responsible for destruction of articular cartilage and bone in rheumatoid arthritis and establishes a new target for therapeutic intervention.

Keywords: Cell Differentiation, Enzyme Mutation, Fibroblast, Genetic Polymorphism, Oncogene

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)3 is a chronic inflammatory disease that occurs in 1% of the population and is characterized by progressive erosive arthritis of multiple joints associated with increased mortality. Although the inflammatory reaction contains numerous cell types, synovial fibroblasts have been identified as the cell responsible for invasion and destruction of cartilage and bone (1–7). Rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts show evidence of transformation indicated by excessive proliferation, loss of contact inhibition, and increased migration (2, 6, 8). Transformation of RA synovial fibroblasts has also been demonstrated in an animal model of RA employing xenograft implants of RA synovium as evidenced by metastasis of implanted synovial fibroblasts with localization and binding to cartilage (9). The mechanism of RA synovial fibroblast transformation has not been identified, but it is critical for the rational design of therapies to prevent joint destruction. Despite evidence for neoplastic transformation of RA synovial fibroblasts, oncogenes potentially responsible for transformation have not been identified. Because gain-of-function mutations in the BRAF oncogene have been shown to transform embryonic fibroblasts but not several other somatic cell types, we examined rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts for the presence of BRAF mutations (8).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

RA Synovial Fibroblasts

Synovial tissue was obtained with Institutional Review Board approval from nine patients with severe RA and an 80-year-old woman with severe osteoarthritis (OA) undergoing joint replacement surgery. Patients with RA included seven women and two men ages 30–74 years. Synovial tissues were digested with collagenase, and the resulting cells were filtered through sterile gauze, washed with Hanks' balanced salt solution, reconstituted in 90% FCS and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and stored frozen in liquid nitrogen until used. Synovial cells (5 × 106-20 × 106) were thawed at 37 °C, immediately diluted 10-fold in DMEM/F12 (1:1) medium, centrifuged, and reconstituted in DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% FCS and Hepes buffer. Synovial cells obtained from synovial tissues were added to T25 tissue flasks for 2 h and then rinsed with Hanks' balanced salt solution to remove non-adherent cells. Fresh DMEM/F12 (1:1) medium containing 5–10% FCS and Hepes buffer was added to the flasks, and the cells were incubated at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2 for 3–14 days. RNA was isolated from first passage synovial fibroblasts with the QIAamp RNA blood mini kit (Qiagen, Sylmar, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

PCR

Reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) was performed with the OneStep RT-PCR kitTM (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The forward primer was: 5′-GGGCCCCGGCTCTCGGTTAT-3′, and the reverse primer was 5′-TGCTACTCTCCTGAACTCTCTCACTCA-3′. These primers are located outside of the coding region of BRAF. Nested PCR was done subsequently with primers inside of the coding region. The forward primer was 5′-GTTCAACGGGGACATGGA-3′ beginning at nucleotide 54 from the ATG start site (exon 1), and the reverse primer was 5′-ATGGTGCGTTTCCTGTCC-3′ beginning at nucleotide 2279 of BRAF. Nested PCR was done with the Easy-ATM high fidelity cloning enzyme and master mix (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) with 1 μl of the RT-PCR product as template. PCR conditions were 1 min of denaturation at 94 °C, 1 min of annealing at 58 °C, and 6 min of extension at 72 °C for 40 cycles. The PCR product was electrophoresed in 0.8% agarose, and cDNA was isolated from the gel with the QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Purified DNA was sequenced by SeqWright, (Houston, TX) with the nested primers as well as internal primers. Nested PCR was also done with the “Fast COLD-PCR” technique performed as described previously and analyzed by electrophoresis in 1.0% Seakem-1.0% NuSieve agarose gels (Lonza Rockland, Inc., Rockland, ME) (10). Fast COLD-PCR takes advantage of the lower melting temperatures of some mutant strands to facilitate their preferential amplification. Primers were designed to amplify a 191-bp fragment centered at Val-600. The unique restriction site SfcI was selected to identify mutations in the first nucleotide of V600R. The forward primer was 5′-ACTGCACAGGGCATGGAT-3′, and the reverse primer was 5′-TCTGGTGCCATCCACAAAA-3′.

Restriction Enzyme Mapping

BRAF contains a single SfcI restriction site that includes the first nucleotide of Val-600 codon. Complete digestion of BRAF with SfcI indicates the presence of wild-type sequence in both PCR-amplified alleles. Mutations in nucleotides comprising the SfcI site are expected to result in partial or incomplete cutting in the presence of excess enzyme. BRAF was digested with SfcI for 20 h at 25 °C with a 10-fold excess of enzyme required for complete digestion.

siRNA Transfection

RA fibroblasts were plated at 10–20% confluence overnight in 24-well plates and transfected in triplicate wells with human BRAF ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool catalog number L-003460-00 and ON-TARGETplus control pool non-targeting pool catalog number D-001810-10-05 (Thermo Scientific Dharmacon) with Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol for ”forward transfection.“ Cells were counted in three separate areas of each well at the time siRNA was added and again 72 h later. Data were expressed as mean number of cells in one microscopic field ± S.D. of triplicate determinations. Significant inhibition of cell growth in response to BRAF siRNA as compared with control siRNA was determined by Student's t test. To confirm down-regulation of BRAF in response to BRAF siRNA, fibroblasts treated with BRAF siRNA and control siRNA were lysed in 10% SDS and evaluated for BRAF and actin by Western blotting to nitrocellulose after SDS-PAGE in 4–20% gradient gels (NuSep, Lawrenceville, GA). Nitrocellulose blots were incubated with rabbit antibodies to BRAF (Abgent, San Diego, CA) and goat antibodies to β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) followed by HRP-conjugated polyclonal goat anti-rabbit and rabbit anti-goat secondary antibodies, respectively. The blots were then developed with SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific) for detection of HRP and imaged with ChemiDoc XRS (Bio-Rad).

RESULTS

Loss of Fibroblast Contact Inhibition

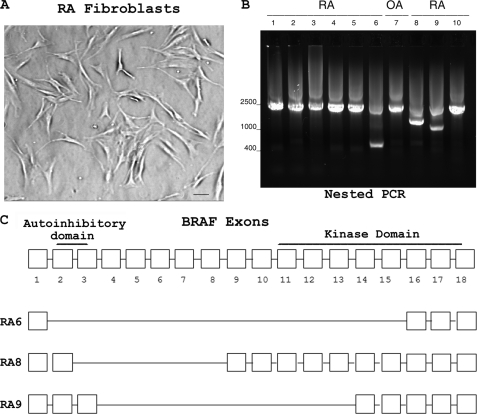

Rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts showed absence of contact inhibition with a representative example shown (Fig. 1A). Loss of contact inhibition suggests that rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts have undergone transformation as described previously (2, 6, 8).

FIGURE 1.

PCR amplification of BRAF from RA fibroblasts. A, loss of fibroblast contact inhibition. Rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts were grown in T25 flasks and observed microscopically. Fibroblast transformation is suggested by the loss of contact inhibition. A representative example is shown. Bar, 20 μm. B, BRAF amplified by RT and nested PCR. Nested PCR amplified a DNA fragment of about 2300 bp in all patients. DNA sequencing confirmed the presence of BRAF. Aberrant splice variants were observed in RA6, RA8, and RA9 as confirmed by DNA sequencing. C, splice variants of BRAF from rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts. Shown is the deletion of exons in splice variants from RA6, RA8, and RA9. RA8 has a splice variant that deletes a portion of the BRAF autoinhibitory domain but retains the kinase domain.

Characterization of BRAF Amplified from Synovial Fibroblasts by RT and Nested PCR

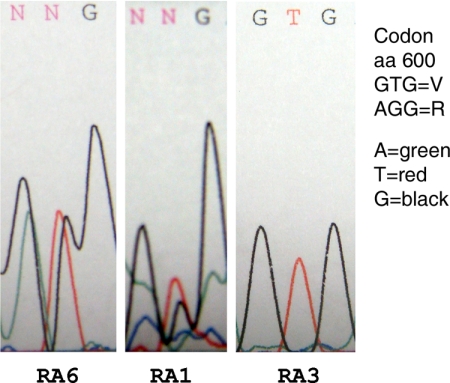

RNA was isolated from first passage fibroblasts and reverse transcribed, and cDNA was amplified by PCR with primers outside of the coding region. Nested PCR with primers within the coding region resulted in a DNA fragment of the expected size with aberrant splice variants also evident in three patients (Fig. 1B). PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis in 0.8% agarose, and DNA was isolated from the gels. Direct DNA sequencing documented full-length BRAF from all patients as well as aberrant splice variants of BRAF in RA patients 6, 8, and 9 (Fig. 1B). DNA sequences of the splice variants showed the following codon deletions: RA6, codons 2–15; RA8, codons 3–8; RA9, codons 4–13 (Fig. 1C). RA8 splice variant retained the kinase domain but lacked exon 3, which contains a portion of the autoinhibitory domain that suppresses kinase activity (11). BRAF splice variants that remove N-terminal autoinhibitory sequences have been associated with enhanced BRAF activity in cancer cells (11, 12). Direct DNA sequencing of full-length transcripts with the antisense nested primer showed two separate sequences corresponding to residue 600 consistent with both wild-type and V600R mutation in synovial fibroblasts from patients 1 and 6 (Fig. 2). V600R is reported as a gain-of-function mutation with strong enhancement (250-fold) of BRAF activity (13).

FIGURE 2.

Mutations of BRAF from rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts. V600R was identified in BRAF from RA synovial fibroblasts in two of nine RA patients. The first two panels show chromatograms from RA1 and RA6 consistent with two separate nucleotide sequences encoding two different amino acids (aa) at residue 600, wild-type and V600R mutant. The third panel is a chromatogram from patient RA3 showing the wild-type nucleotide sequence encoding valine at residue 600.

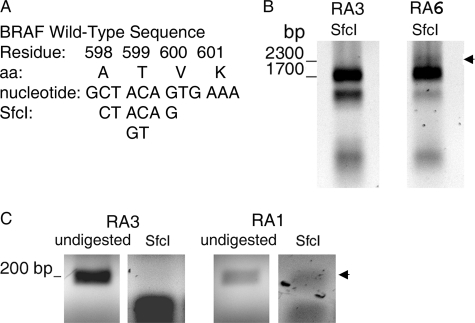

Restriction Enzyme Mapping

To confirm the mutations in BRAF cDNA, we performed restriction mapping of the region that includes Val-600. SfcI is a unique restriction site in BRAF that includes the first nucleotide of Val-600 codon (Fig. 3A). Incomplete digestion of the 2300-bp BRAF cDNA to 1700- and 600-bp fragments in the presence of excess enzyme confirms the mutation V600R in cDNA. Therefore, cDNA from RA6 was digested with a 10-fold excess of SfcI and examined by gel electrophoresis. Incomplete digestion of the 2300-bp PCR product from RA6 was observed, consistent with the V600R mutation in RA6 cDNA (Fig. 3B). In contrast, SfcI completely digested the 2300-bp PCR product from RA3 without mutation of BRAF. To confirm the Val-600 mutation in RA1, we used Fast COLD-PCR to enhance selection of mutant DNA strands as described previously (10). As shown, digestion of a 191-bp fragment, centered on Val-600, with an excess of SfcI failed to completely digest RA1 cDNA, consistent with the V600R mutation (Fig. 3C). In contrast, SfcI completely digested the 191 bp from RA3 without mutation of BRAF to produce two fragments, each approximately half the size of the 191-bp fragment.

FIGURE 3.

Restriction enzyme mapping. A, the SfcI restriction site includes the first nucleotide of the codon for BRAF residue 600. aa, amino acids. B, incomplete SfcI digestion of the 2300-bp BRAF cDNA obtained by PCR (inverted image) is consistent with V600R of BRAF from RA6. In contrast, the 2300-bp BRAF cDNA from RA3 without BRAF mutation shows complete digestion by SfcI. C, incomplete SfcI digestion of the 191-bp BRAF cDNA fragment obtained by Fast COLD-PCR (inverted image) is consistent with V600R of BRAF from RA1. In contrast, the 191-bp BRAF cDNA from RA3 without BRAF mutation shows complete digestion by SfcI. Arrows in B and C indicate uncleaved cDNA following digestion with excess SfcI.

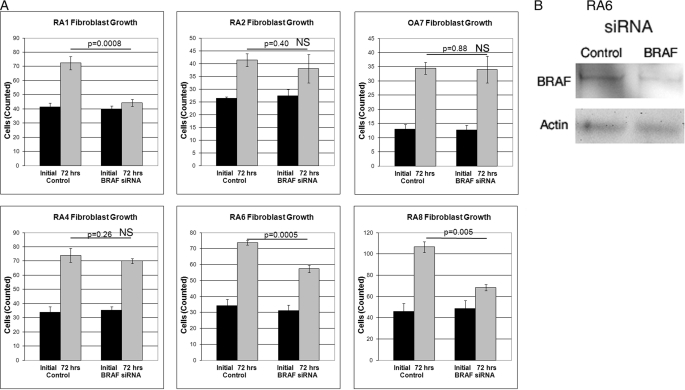

BRAF Function in RA Synovial Fibroblasts

Suppression of BRAF by siRNA inhibited growth of fibroblasts from both patients (RA1 and RA6) with V600R mutations of BRAF and from RA8 with the BRAF splice variant with an intact kinase domain but loss of a portion of the autoinhibitory domain. In contrast, BRAF-specific siRNA did not inhibit growth of synovial fibroblasts from RA2 and RA4 without mutations of BRAF. In addition, BRAF siRNA did not inhibit growth of fibroblasts from patient OA7 with osteoarthritis (Fig. 4A). BRAF siRNA inhibited the production of BRAF as demonstrated by Western blotting of synovial fibroblast lysates from patient RA6 (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Inhibition of RA fibroblast growth by BRAF siRNA. A, synovial fibroblasts from five RA patients and one OA patient were cultured for 72 h in the presence of control and BRAF-specific siRNA. Significant inhibition of growth in response to BRAF siRNA was observed in fibroblasts from RA1 and RA6 with a V600R mutation of BRAF and in RA8 with a BRAF splice variant containing a partial deletion of the autoinhibitory domain. B, BRAF siRNA inhibits production of BRAF. Synovial fibroblasts from RA6 were incubated with BRAF siRNA for 72 h and assessed for BRAF production by Western blot. Actin served as a loading control.

DISCUSSION

The RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway is referred to as the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. Activation of MAPK results in cell proliferation, survival, and transformation. BRAF is one of three isoforms of RAF, but only BRAF is frequently mutated in various cancers (14). Some mutations in the activation segment of BRAF kinase have gain-of-function activity responsible for cellular transformation leading to melanoma and other cancers (13). The observation that mutations of BRAF induce transformation of embryonic fibroblasts, but not several other somatic cells, led us to search for similar mutations in RA synovial fibroblasts as a mechanism for their transformation (8). Residue 600 is most frequently mutated with V600E predominating. V600R occurs less frequently but is also a strong (250-fold) enhancer of BRAF kinase activity (13). Identification of V600R gain-of-function mutations of BRAF in RA synovial fibroblasts in RA patients is consistent with this as a potential mechanism for synovial fibroblast transformation in the pathogenesis of erosive joint disease in some patients. BRAF siRNA inhibited growth of synovial fibroblasts from both patients with BRAF V600R mutations, confirming the functional significance of BRAF mutations on synovial fibroblast growth.

BRAF has two normal isoforms associated with multiple splice variants. However, aberrant splice variants of BRAF were recently reported in both colon and thyroid cancers (12, 15). Some aberrant splice variants have been shown to activate the MAP kinase signaling pathway, suggesting that BRAF splice variants may function as an alternative mechanism for oncogenic BRAF activation (15). Consistent with this idea, a BRAF N-terminal autoinhibitory domain has been identified, and loss of the inhibitory domain resulted in an increase BRAF kinase activity (9). Thus, certain aberrant isoforms that exclude portions of the autoinhibitory domain but retain the kinase domain may have enhanced kinase activity. In our study, one RA patient (RA8) had an aberrant BRAF splice variant with deletion of exon 3 containing a portion of the autoinhibitory domain; however, an intact kinase domain was retained. Proliferation of synovial fibroblasts from RA8 was inhibited by BRAF-specific siRNA. The finding of gain-of-function BRAF mutations and splice variants is consistent with multiple mechanisms involving BRAF that may lead to transformation of fibroblasts in RA synovium.

Patients with cancers due to mutations of oncogenes often produce antibodies to altered or cryptic epitopes. Mutations of BRAF occur in 15% of cancers with the highest incidence in melanomas where 9% of patients have serum antibodies specific for BRAF (16, 17). In a recent study, 9 of 19 patients with rheumatoid arthritis were reported to have serum antibodies to BRAF assayed by Western blot, a finding that is consistent with the presence of an altered BRAF protein in these patients (18). We did not have matched serum samples to evaluate a correlation between the presence of serum antibodies to BRAF and BRAF mutations or aberrant splice variants in synovial fibroblasts. Further studies are required to evaluate these associations. It is likely that our study underestimates the frequency of BRAF mutations in RA synovial fibroblasts due to the technical difficulty inherent in identifying heterozygous mutations. In addition, some aberrant splice variants lacking the autoinhibitory domain would be missed as a result of our selection of PCR primers requiring the presence of exon 1.

Whether mutations or aberrant splice variants of BRAF alone are sufficient to explain synovial fibroblast transformation in a subset of RA patients is unknown as several oncogenes may work in concert to produce pathological effects. For example, expression of BRAF V600E in human melanocytes induces cell cycle arrest and senescence, whereas concurrent inhibition of p53 results in cellular transformation (19). This is of interest in view of studies that identified abundant mutations in the TP53 oncogene in RA synovial fibroblasts (20, 21). However, mutant BRAF alone was shown to be sufficient to transform embryonic fibroblasts (8).

BRAF is a therapeutic target in melanoma as down-regulation of BRAF induces apoptosis in cancer cells (22). Our study suggests that BRAF may also be an important therapeutic target in some patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Acknowledgment

We thank Joseph Gera, Ph.D. for discussions and reviewing the manuscript.

Footnotes

- RA

- rheumatoid arthritis

- OA

- osteoarthritis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Müller-Ladner U., Kriegsmann J., Franklin B. N., Matsumoto S., Geiler T., Gay R. E., Gay S. (1996) Am. J. Pathol. 149, 1607–1615 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pap T., Müller-Ladner U., Gay R. E., Gay S. (2000) Arthritis Res. 2, 361–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buckley C. D., Pilling D., Lord J. M., Akbar A. N., Scheel-Toellner D., Salmon M. (2001) Trends Immunol. 22, 199–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Müller-Ladner U., Pap T., Gay R. E., Neidhart M., Gay S. (2005) Nat. Clin. Pract. Rheumatol. 1, 102–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pap T., Meinecke I., Müller-Ladner U., Gay S. (2005) Ann. Rheum. Dis. 64, Suppl. 4, iv52–iv54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karouzakis E., Neidhart M., Gay R. E., Gay S. (2006) Immunol. Lett. 106, 8–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huber L. C., Distler O., Tarner I., Gay R. E., Gay S., Pap T. (2006) Rheumatology 45, 669–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mercer K., Giblett S., Green S., Lloyd D., DaRocha Dias S., Plumb M., Marais R., Pritchard C. (2005) Cancer Res. 65, 11493–11500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lefèvre S., Knedla A., Tennie C., Kampmann A., Wunrau C., Dinser R., Korb A., Schnäker E. M., Tarner I. H., Robbins P. D., Evans C. H., Stürz H., Steinmeyer J., Gay S., Schölmerich J., Pap T., Müller-Ladner U., Neumann E. (2009) Nat. Med. 15, 1414–1420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li J., Makrigiorgos G. M. (2009) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37, 427–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tran N. H., Wu X., Frost J. A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 16244–16253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baitei E. Y., Zou M., Al-Mohanna F., Collison K., Alzahrani A. S., Farid N. R., Meyer B., Shi Y. (2009) J. Pathol. 217, 707–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wan P. T., Garnett M. J., Roe S. M., Lee S., Niculescu-Duvaz D., Good V. M., Jones C. M., Marshall C. J., Springer C. J., Barford D., Marais R. (2004) Cell 116, 855–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garnett M. J., Marais R. (2004) Cancer Cell 6, 313–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seth R., Crook S., Ibrahem S., Fadhil W., Jackson D., Ilyas M. (2009) Gut 58, 1234–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies H., Bignell G. R., Cox C., Stephens P., Edkins S., Clegg S., Teague J., Woffendin H., Garnett M. J., Bottomley W., Davis N., Dicks E., Ewing R., Floyd Y., Gray K., Hall S., Hawes R., Hughes J., Kosmidou V., Menzies A., Mould C., Parker A., Stevens C., Watt S., Hooper S., Wilson R., Jayatilake H., Gusterson B. A., Cooper C., Shipley J., Hargrave D., Pritchard-Jones K., Maitland N., Chenevix-Trench G., Riggins G. J., Bigner D. D., Palmieri G., Cossu A., Flanagan A., Nicholson A., Ho J. W., Leung S. Y., Yuen S. T., Weber B. L., Seigler H. F., Darrow T. L., Paterson H., Marais R., Marshall C. J., Wooster R., Stratton M. R., Futreal P. A. (2002) Nature 417, 949–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fensterle J., Becker J. C., Potapenko T., Heimbach V., Vetter C. S., Bröcker E. B., Rapp U. R. (2004) BMC Cancer 4, 62–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Auger I., Balandraud N., Rak J., Lambert N., Martin M., Roudier J. (2009) Ann. Rheum. Dis. 68, 591–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu H., McDaid R., Lee J., Possik P., Li L., Kumar S. M., Elder D. E., Van Belle P., Gimotty P., Guerra M., Hammond R., Nathanson K. L., Dalla Palma M., Herlyn M., Xu X. (2009) Am. J. Pathol. 174,:2367–2377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inazuka M., Tahira T., Horiuchi T., Harashima S., Sawabe T., Kondo M., Miyahara H., Hayashi K. (2000) Rheumatology 39, 262–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamanishi Y., Boyle D. L., Green D. R., Keystone E. C., Connor A., Zollman S., Firestein G. S. (2005) Arthritis Res. Ther. 7, R12–R18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karasarides M., Chiloeches A., Hayward R., Niculescu-Duvaz D., Scanlon I., Friedlos F., Ogilvie L., Hedley D., Martin J., Marshall C. J., Springer C. J., Marais R. (2004) Oncogene 23, 6292–6298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]