Abstract

Chelatable zinc is important in brain function, and its homeostasis is maintained to prevent cytotoxic overload. However, certain pathologic events result in intracellular zinc accumulation in lysosomes and mitochondria. Abnormal lysosomes and mitochondria are common features of the human lysosomal storage disorder known as mucolipidosis IV (MLIV). MLIV is caused by the loss of TRPML1 ion channel function. MLIV cells develop large hyperacidic lysosomes, membranous vacuoles, mitochondrial fragmentation, and autophagic dysfunction. Here, we observed that RNA interference of mucolipin-1 gene (TRPML1) in HEK-293 cells mimics the MLIV cell phenotype consisting of large lysosomes and membranous vacuoles that accumulate chelatable zinc. To show that abnormal chelatable zinc levels are indeed correlated with MLIV pathology, we quantified its concentration in cultured MLIV patient fibroblast and control cells with a spectrofluorometer using N-(6-methoxy-8-quinolyl)-p-toluene sulfonamide fluorochrome. We found a significant increase of chelatable zinc levels in MLIV cells but not in control cells. Furthermore, we quantified various metal isotopes in whole brain tissue of TRPML1−/− null mice and wild-type littermates using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry and observed that the zinc-66 isotope is markedly elevated in the brain of TRPML1−/− mice when compared with controls. In conclusion, we show for the first time that the loss of TRPML1 function results in intracellular chelatable zinc dyshomeostasis. We propose that chelatable zinc accumulation in large lysosomes and membranous vacuoles may contribute to the pathogenesis of the disease and progressive cell degeneration in MLIV patients.

Keywords: Ion channels, Iron, Lysosomal storage disease, Lysosomes, Zinc

Introduction

Zinc (Zn2+) is a redox-inert yet crucial trace element for virtually all organisms. Zn2+ is second to iron in biological trace metal abundance and is known to play an important role in human brain function (1, 2). Some enzymes require Zn2+ as co-factors, but many proteins use it for structural stability and thus are tightly bound (non-chelatable form) (3). A chelatable pool of Zn2+ is present in cells, most notably in glutamatergic vesicles, and gets released at the neuronal synapse during normal and pathological states (4, 5). Because high levels of chelatable Zn2+ or any trace metals produce cellular and mitochondrial toxicity (1, 6, 7), it is imperative that Zn2+ homeostasis is actively maintained inside and outside of the cells. Certain pathological events such as epilepsy, cerebral stroke, and traumatic brain injury result in uncontrolled release and accumulation of chelatable Zn2+ in neurons (1, 8) via voltage-gated or calcium-permeable ion channels (9). Furthermore, endosomes, autophagosomes, and lysosomes, which are critical organelles involved in the recycling and degradation of many proteins, are known compartments where chelatable Zn2+ accumulates upon cellular perturbation (10–12). Interestingly, chelatable Zn2+ appears to mediate vacuolar formation in primary retinal cells exposed to ethambutol (an antituberculosis drug known for its ocular toxicity) (13, 14) and autophagic vacuole formation in astrocytes upon exposure to hydrogen peroxide (12). Consequently, high levels of chelatable Zn2+ accrue in ethambutol-induced vacuoles, which induce lysosomal membrane permeabilization and retinal cell death (13). The association of chelatable Zn2+ in neurodegeneration led us to study its potential role in mucolipidosis IV (MLIV),3 a developmental disorder that results in large hyperacidic lysosomes, membranous vacuole formation, autophagic dysfunction, and mitochondrial fragmentation (15–18). MLIV is an autosomal, recessive disease that generally results in brain and cognitive dysfunction, corneal clouding, and retinal cell degeneration leading to blindness, anemia, and achlorhydria (lack of gastric acid production in the stomach) (19). It is caused by the loss of transient receptor potential mucolipin-1 (TRPML1) ion channel function. TRPML1 is widely expressed in tissues and organs. It is a lysosomal membrane protein believed to play a role in endosomal-lysosomal interaction, lysosomal pH stability, lysosome maturation, lipid metabolism, and autophagy (16–18, 20, 21). TRPML1 is an inwardly rectifying, non-selective cation channel that is permeable to calcium (Ca2+) and other divalent trace metals such as Zn2+, iron (Fe2+), and manganese (Mn2+) (22–24). It is noteworthy that histochemical Prussian blue staining shows that chelatable Fe2+ levels in the cytosol of MLIV fibroblasts appear to be reduced, whereas levels in the lysosomes appear elevated when compared with control cells (22). These findings suggest that an impairment in chelatable Fe2+ permeability may be causal to MLIV disease (22). Notwithstanding, we hypothesize that chelatable Zn2+, and not Fe2+, could be the mitigating factor in the cellular pathology and progressive cell degeneration in MLIV disease. In this report, we investigated whether chelatable Zn2+ invariably accumulates within lysosomes of cells following RNA interference of TRPML1 and whether its concentrations are significantly perturbed upon the loss of TRPML1 ion channel function in MLIV patient fibroblast cells, as well as in the brain tissue of TRPML1−/− knock-out mice.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chelatable Zinc Fluorescence Microscopy and Spectrofluorometric Quantification

For confocal microscopy, we used the membrane-permeable fluorescent dyes, FluoZin-3TM (Kd ∼15 nm; excitation = 494 nm, emission = 516 nm) and Newport GreenTM DCF (Kd ∼1 μm; excitation = 505 nm, emission = 535 nm) (Invitrogen). A membrane-impermeable FluoZin-3 was used as negative control. For relative fluorescence quantification, we measured chelatable Zn2+ levels with a BioTek Synergy 2 spectrofluorometer using the fluorochrome N-(6-methoxy-8-quinolyl)-p-toluene sulfonamide (TSQ, Kd ∼10 nm; excitation = 380 nm, emission = 495 nm) that strongly fluoresces when bound by Zn2+ (25). All three fluorescent dyes used in the study are chelatable Zn2+-specific and have low affinity for abundant metals such as calcium and magnesium ions (26, 27).

RNA Interference (RNAi)

We validated the effect of a short hairpin RNA vector targeting human mucolipin-1 gene (TRPML1 shRNA-1208) as described previously (28, 29) and human mucolipin-2 (TRPML2) gene (supplemental Fig. S1). A scrambled shRNA vector control (OriGene Technologies) was also tested and validated (supplemental Fig. S1). Human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 cells were transfected with TRPML1 and -2 and scrambled shRNA vectors (2 μg) and processed for confocal or electron microscopy (EM) 48 h after transfection. Standard EM technique was performed on TRPML1 RNAi-treated and untreated cells as described (30). For confocal microscopy, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), incubated for 30–60 min with either FluoZin-3 or Newport Green DCF (1 μm; Invitrogen) to detect chelatable Zn2+, and incubated with either LysoTrackerTM Red DND-99 or Blue DND-22 (0.5 nm; Invitrogen) to detect lysosomes or acidic compartments. LysoTracker Blue DND-22 was used in experiments using TRPML2 and scrambled control shRNA because both plasmids were tagged with a red fluorescent protein marker to monitor expression. The cells were then washed twice with PBS, mounted on slides with ProLongTM Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen), and imaged without fixation. The red channel was used to show the LysoTracker Blue DND-22 micrographs of TRPML2 RNAi and scrambled RNAi. In other experiments, DAPI was added to stain the cell nucleus.

Primary Cultures of MLIV and Control Fibroblasts

Two MLIV patient skin fibroblast cells (GM 02048 and GM 02527) and two control skin fibroblast cells (GM 00408 and GM 03440) were purchased from Coriell Cell Repositories (Camden, NJ) and cultured in triplicates according to their recommendations. The cells were washed twice with PBS, incubated with TSQ (1 mm) for 30–60 min, washed twice with PBS, and assayed using a BioTek Synergy 2 spectrofluorometer. The relative fluorescence units obtained from Zn2+-TSQ chelates were normalized by total cell numbers per trial using the Cell TiterGlo® viability luminescence kit (Promega) to control for any assay variations.

Brain Metal Isotope Analysis

We obtained brain tissues (1 gm) from TRPML1−/− knock-out (KO) mice (n = 4), and wild-type (WT) littermate controls (n = 3). The frozen brain samples were sent to the California State University Long Beach, Institute for Integrated Research, Materials, Environments, and Society (IIRMES) Core facility for inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) analysis of various metal isotopes such as sodium-23, calcium-43, calcium-44, magnesium-24, aluminum-27, chromium-52, manganese-55, iron-54, iron-57, copper-63, copper-65, and zinc-66. The samples were normalized by total protein content prior to ICP-MS analysis to control for any handling errors introduced during ICP-MS analysis. Data are represented as means ± S.E. and analyzed for statistical significance using Student's t test (two-tailed, p < 0.05).

RESULTS

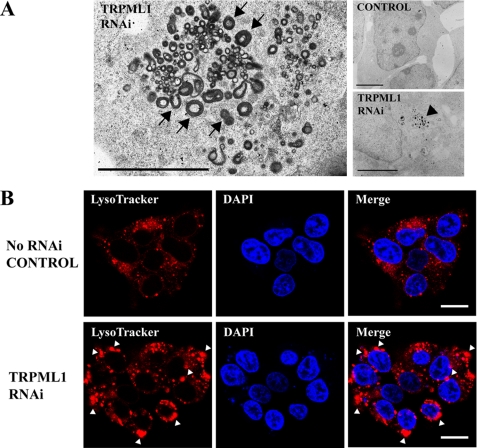

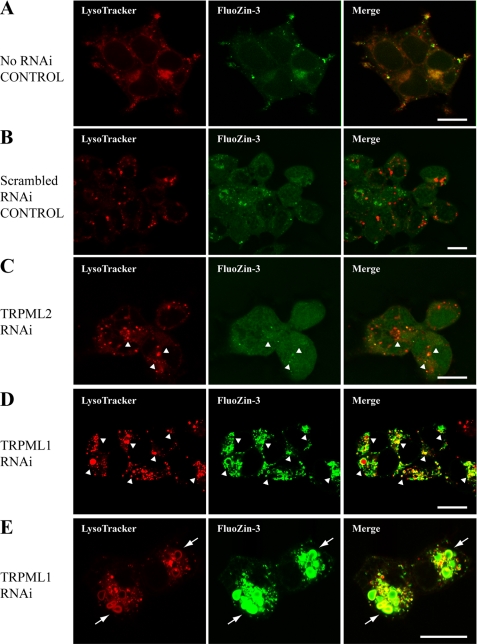

To model MLIV in vitro, we used RNAi to knock down endogenous TRPML1 protein levels in HEK-293 cells. Electron microscopy showed that TRPML1 RNAi exhibited electron-dense, large membranous vacuoles that were characteristic of MLIV cell phenotype (Fig. 1A). RNAi knockdown of cells that normally express TRPML1 has been reported to produce such cell phenotype by 48–72 h (21, 31). Interestingly, phagophore-like membrane structures were also apparent near dense vacuolar structures (horseshoe or half-circle shapes, Fig. 1A, arrows); phagophores are double membrane structures that initiate autophagy. Fluorescence microscopy showed that lysosomes in these TRPML1 RNAi-treated cells were more pronounced and much larger in comparison with those of untreated control cells (Fig. 1B). Indeed, both non-RNAi-treated control and scrambled RNAi-treated control cells had mostly smaller lysosomes with sporadic FluoZin-3 positive Zn2+ fluorescence (Fig. 2, A and B), or Newport Green DCF (supplemental Fig. S2). The TRPML2 RNAi-treated cells occasionally had large LysoTracker-positive lysosomes that co-fluoresced with FluoZin-3 (Fig. 2C). However, the size of the lysosomes in these TRPML2 RNAi-treated cells appeared similar to untreated and scrambled RNAi control cells, whereas in TRPML1 RNAi-treated cells, both lysosomes and vacuolar structures that were positive for LysoTracker were brightly fluorescent for chelatable Zn2+ as evidenced by either FluoZin-3 (Fig. 2, D and E) or Newport Green DCF stain (supplemental Fig. S2). No fluorescence was observed using the non-permeable FluoZin-3 control dye (not shown). Noteworthy is a phagophore-like structure that can be seen from TRPML1 RNAi-treated cells co-fluorescing with LysoTracker and FluoZin-3 (Fig. 2E).

FIGURE 1.

Electron and confocal micrographs of TRPML1 RNAi-treated and control HEK-293 cells. A, representative electron micrographs of TRPML1 RNAi-treated cells show electron-dense, membranous vacuoles and inclusion bodies (right panel, arrow) when compared with control. Phagophore-like structures exemplified by half-circle or horseshoe-shaped membranes can be seen near vacuolar organelles (arrowheads). Scale bar = 1 μm. B, representative confocal micrographs showing untreated control (top panel) and TRPML1 RNAi-treated HEK-293 cells (bottom panel). Lysosomes (red) are positive for LysoTracker fluorescence in control and RNAi-treated cells; however, a marked number of large lysosomal structures are only observed in TRPML1 RNAi-treated cells. Enlarged and hyperacidic lysosomes in cells are phenotypic features of ML-IV pathology. The cell nucleus (blue) was stained with DAPI. Scale bar = 10 μm.

FIGURE 2.

Representative confocal micrographs of control and RNAi-treated HEK-293 cells stained with LysoTracker for lysosomes and FluoZin-3 for chelatable Zn2+. A, untreated control. B, scrambled RNAi-treated control. C, TRPML2 RNAi-treated cells. D and E, TRPML1 RNAi-treated cells. In A and B, some lysosomes (red) co-fluoresce with chelatable Zn2+ (green), but lysosomes in these cells are relatively similar in size. In C, an occasional increase in the size of lysosomes corresponds with positive FluoZin-3 stain (arrowheads). Note, however, that TRPML1 RNAi-treated cells in D and E have a relatively greater number of large lysosomes and vacuoles that also exhibit bright FluoZin-3 fluorescence indicative of chelatable Zn2+ accumulation (arrowheads). Higher magnification in E shows phagophore-like structures fluorescing both red and green (arrows) near other vacuolar organelles. The red channel was used to show the LysoTracker Blue DND-22 micrographs of TRPML2 RNAi and scrambled RNAi. Scale bars = 10 μm.

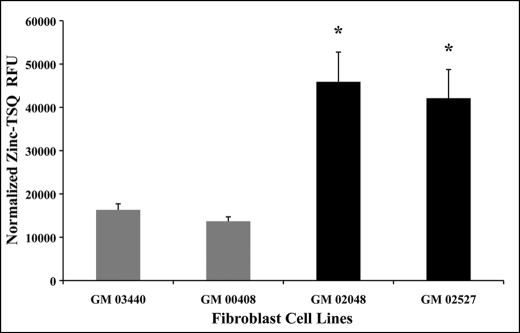

To determine whether chelatable Zn2+ levels were abnormal in TRPML1 RNAi-treated HEK-293 cells when compared with controls, we performed TSQ spectrofluorometric analysis of the samples. We observed an increase of relative Zn2+-TSQ fluorescence in TRPML1 RNAi-treated cells but not with untreated, scrambled RNAi, and TRPML2 RNAi controls (not shown). To verify whether this observation was relevant within the context of MLIV pathology, we quantified chelatable Zn2+ concentrations in primary cultured MLIV skin fibroblast and non-patient control cells. Spectrofluorometric quantification revealed a significant 2–3-fold increase in relative Zn2+-TSQ fluorescence in fibroblasts of MLIV patients (GM 02048 and GM 02527) when compared with control fibroblast cells (GM 03440 and GM 00408) (Fig. 3). Because neurons are affected by MLIV, our in vitro findings prompted us to further study Zn2+ levels using whole brain tissues of TRPML1−/− KO mice and WT littermates. Indeed, ICP-MS analysis showed a small but significant increase in the concentration of zinc isotope-66 (66Zn) from TRPML1−/− KO mouse brain tissues (11.16 ± 0.5 μg/g; p < 0.05) but not from WT littermate controls (9.34 ± 0.4 μg/g). No other metal isotopes analyzed were found to be significantly different in these samples (not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Spectrofluorometric analysis of intracellular chelatable zinc concentrations in cultured MLIV patient skin fibroblasts and control cells. Normalized relative fluorescence units (RFU) of Zn2+-TSQ signals from MLIV fibroblast lines (GM 02048 and GM 02527, black bars) are significantly higher than control fibroblast lines (GM 03440 and GM 00408, gray bars). This result shows that chelatable zinc levels are elevated in MLIV cells and that chelatable zinc dyshomeostasis is directly associated with the loss of TRPML1 function. Data are represented as means ± S.E., n = 4 independent trials, *, p < 0.05, Student's t test, two-tailed analysis.

DISCUSSION

Our study shows that the loss of TRPML1 function leads to significant accumulation of chelatable Zn2+ in large lysosomes and vacuolar structures. Chelatable Zn2+ fluorescence is observed within lysosomal lumen and vacuolar lumen. These results intriguingly resemble what has been reported as a Zn2+ buildup in ethambutol-induced vacuoles in retinal cells (13, 14) and hydrogen peroxide-induced autophagic vacuoles in astrocytes (12). Chelatable Zn2+ appears to mediate autophagic and lysosomal vacuole formation in these aforementioned cells because Zn2+ chelation reduces such an effect, but whether it could also be involved in vacuolar formation upon the loss of TRPML1 function remains to be determined. Nevertheless, significant chelatable Zn2+ elevation was evident in MLIV patient fibroblast cells, as well as in the whole brain tissue of TRPML1−/− KO mice. It would have been ideal to study the levels of zinc using human postmortem MLIV brain tissue in addition to the mouse model, but unfortunately, such precious tissue was not available for our investigation.

We found a 2–3-fold increase in chelatable Zn2+ levels using spectrofluorometry, whereas our ICP-MS data showed a modest increase in 66Zn isotope levels. The difference in magnitude can be explained by methodological differences; the former measured chelatable levels, whereas the latter measured total tissue zinc isotope contents. Moreover, diet and drinking water in rodents have been shown to influence brain zinc levels (32, 33), making whole brain tissue analysis of trace metals from rodents more prone to variability in comparison with cultured cells where known amounts of trace metals are found in media or buffers. Nevertheless, we clearly established that abnormal Zn2+ metabolism is present in MLIV cells. Specifically, the loss of TRPML1 appears to increase the amount of chelatable Zn2+ in the lysosomes but not in untreated control, scrambled RNAi-treated, and TRPML2 RNAi-treated cells. Although RNAi-mediated TRPML2 knockdown has been previously shown to exhibit similar EM-dense membranous structure in HeLa cells (31), our results showed only a few large lysosomes that also co-localized with chelatable Zn2+ fluorescence despite the fact that the TRPML2 shRNA vector efficiently knocked down heterologously overexpressed TRPML2 protein. This observation suggests that the loss or disruption of TRPML1 protein function makes cells highly vulnerable to intracellular chelatable Zn2+ dyshomeostasis.

Recently, histochemical evidence using Prussian blue stain showed that chelatable Fe2+ levels in the cytosol were reduced, whereas its levels in lysosomes were elevated in MLIV fibroblast cells with distinct mucolipin-1 gene mutation (22). However, we did not observe a significant change in iron isotope levels from TRPML1−/− KO mouse brain samples, but rather found that 66Zn levels were significantly different. Furthermore, colorimetric measurement of total Fe2+ levels in TRPML1 RNAi-treated HEK-293 cells did not show significant changes when compared with untreated control.4 It is possible that differences in the techniques may explain such discrepancies; the previous study looked at chelatable Fe2+ concentrations in MLIV fibroblast using Prussian blue stain (22), whereas our collaborators4 quantified total Fe2+ concentrations of TRPML1 RNAi-treated cultured cells using the wet-ash method, and we quantified levels of iron isotopes from TRPML1−/− KO mice using ICP-MS.

The known cellular and mitochondrial toxicities of chelatable Zn2+ (1, 6, 7) suggest that our findings could be relevant to cell death and progressive degeneration in MLIV. Likewise, high levels of dietary zinc have been shown to induce iron deficiency and anemia in rodents (34). Because anemia is a clinical feature of MLIV, it would be interesting to know whether changes in systemic and/or tissue zinc levels of MLIV patients correlate with iron deficiency and anemia.

In conclusion, we showed for the first time that Zn2+ metabolism is impaired in cells lacking a functional TRPML1 ion channel. These findings support our hypothesis that TRPML1 dysfunction leads to changes in concentrations of chelatable Zn2+ pool, but not Fe2+, as evidenced by both cellular and in vivo models of MLIV disease. Future research should investigate whether chelatable Zn2+ elevation contributes to cell death and progressive degeneration of neuronal and retinal cells using the mouse model for MLIV and whether the use of zinc-specific chelator could reverse such negative effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the technical support given by Karn Sorasaenee, Steve Karl, Mohammad Samie, and Katrina Taylor. We also thank Dr. Maria Linder for help and technical advice in iron analysis. We also thank Dr. Maria Linder and Dr. Sean Murray for critiquing the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 NS39995 (to S. A. S.). This work was also partially supported by Doris Howell-CSUPERB research scholarships (to J. L. E. and J. A. E.), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute undergraduate research program, and National Science Foundation Grant MCB 920127 (to M. P. C.). A preliminary account of this work was presented in the Experimental Biology 2010 meeting on April 26, 2010 in Anaheim, CA.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

C. Morrison and M. Linder, personal communication.

- MLIV

- mucolipidosis IV

- ICP-MS

- inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry

- TSQ

- N-(6-methoxy-8-quinolyl)-p-toluene sulfonamide.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cuajungco M. P., Lees G. J. (1997) Neurobiol. Dis. 4, 137–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frederickson C. J., Koh J. Y., Bush A. I. (2005) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 449–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frederickson C. J. (1989) Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 31, 145–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howell G. A., Welch M. G., Frederickson C. J. (1984) Nature 308, 736–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuajungco M. P., Lees G. J. (1998) Brain Res. 799, 118–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi D. W., Yokoyama M., Koh J. (1988) Neuroscience 24, 67–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sensi S. L., Ton-That D., Sullivan P. G., Jonas E. A., Gee K. R., Kaczmarek L. K., Weiss J. H. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 6157–6162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi D. W., Koh J. Y. (1998) Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 21, 347–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sensi S. L., Canzoniero L. M., Yu S. P., Ying H. S., Koh J. Y., Kerchner G. A., Choi D. W. (1997) J. Neurosci. 17, 9554–9564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falcón-Pérez J. M., Dell'Angelica E. C. (2007) Exp. Cell Res. 313, 1473–1483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwang J. J., Lee S. J., Kim T. Y., Cho J. H., Koh J. Y. (2008) J. Neurosci. 28, 3114–3122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee S. J., Cho K. S., Koh J. Y. (2009) Glia 57, 1351–1361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung H., Yoon Y. H., Hwang J. J., Cho K. S., Koh J. Y., Kim J. G. (2009) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 235, 163–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon Y. H., Jung K. H., Sadun A. A., Shin H. C., Koh J. Y. (2000) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 162, 107–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jennings J. J., Jr., Zhu J. H., Rbaibi Y., Luo X., Chu C. T., Kiselyov K. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 39041–39050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soyombo A. A., Tjon-Kon-Sang S., Rbaibi Y., Bashllari E., Bisceglia J., Muallem S., Kiselyov K. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 7294–7301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Venugopal B., Mesires N. T., Kennedy J. C., Curcio-Morelli C., Laplante J. M., Dice J. F., Slaugenhaupt S. A. (2009) J. Cell. Physiol. 219, 344–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vergarajauregui S., Connelly P. S., Daniels M. P., Puertollano R. (2008) Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, 2723–2737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amir N., Zlotogora J., Bach G. (1987) Pediatrics 79, 953–959 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kogot-Levin A., Zeigler M., Ornoy A., Bach G. (2009) Pediatr. Res. 65, 686–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miedel M. T., Rbaibi Y., Guerriero C. J., Colletti G., Weixel K. M., Weisz O. A., Kiselyov K. (2008) J. Exp. Med. 205, 1477–1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong X. P., Cheng X., Mills E., Delling M., Wang F., Kurz T., Xu H. (2008) Nature 455, 992–996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grimm C., Cuajungco M. P., van Aken A. F., Schnee M., Jörs S., Kros C. J., Ricci A. J., Heller S. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 19583–19588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu H., Delling M., Li L., Dong X., Clapham D. E. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 18321–18326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frederickson C. J., Kasarskis E. J., Ringo D., Frederickson R. E. (1987) J. Neurosci. Methods 20, 91–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gee K. R., Zhou Z. L., Ton-That D., Sensi S. L., Weiss J. H. (2002) Cell Calcium 31, 245–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang P., Guo Z. (2004) Coord. Chem. Rev. 248, 205–229 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grimm C., Jörs S., Saldanha S. A., Obukhov A. G., Pan B., Oshima K., Cuajungco M. P., Chase P., Hodder P., Heller S. (2010) Chem. Biol. 17, 135–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samie M. A., Grimm C., Evans J. A., Curcio-Morelli C., Heller S., Slaugenhaupt S. A., Cuajungco M. P. (2009) Pflugers Arch 459, 79–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirose K., Westrum L. E., Cunningham D. E., Rubel E. W. (2004) J. Comp. Neurol. 470, 164–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeevi D. A., Frumkin A., Offen-Glasner V., Kogot-Levin A., Bach G. (2009) J. Pathol. 219, 153–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flinn J. M., Hunter D., Linkous D. H., Lanzirotti A., Smith L. N., Brightwell J., Jones B. F. (2005) Physiol. Behav. 83, 793–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Linkous D. H., Adlard P. A., Wanschura P. B., Conko K. M., Flinn J. M. (2009) J. Alzheimers Dis. 18, 565–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yanagisawa H., Miyakoshi Y., Kobayashi K., Sakae K., Kawasaki I., Suzuki Y., Tamura J. (2009) Toxicol. Lett. 191, 15–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.