Abstract

In the host immune system, leukocytes are often exposed to multiple inflammation inducers. NF-κB is of considerable importance in leukocyte function because of its ability to activate the transcription of many proinflammatory immediate-early genes. Tremendous efforts have been made toward understanding how NF-κB is activated by various inducers. However, most research on NF-κB regulation has been focused on understanding how NF-κB is activated by a single inducer. This is unlike the situation in the human immune system where multiple inflammation inducers, including both exogenous and endogenous mediators, are present concurrently. We now present evidence that the formylated peptide f-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP), a bacterial chemoattractant, synergizes with TNFα to induce NF-κB activation and the resultant inflammatory response in vitro and in vivo. The mechanism of synergistic activation of NF-κB by bacterial fMLP and TNFα may be involved in the induction of RelA acetylation, which is regulated by p38 MAPK. Thus, this study provides direct evidence for the synergistic induction of NF-κB-dependent inflammatory responses by both exogenous and endogenous inducers. The ability of fMLP to synergize with TNFα and activate NF-κB represents a novel and potentially important mechanism through which bacterial fMLP not only attracts leukocytes but also directly contributes to inflammation by synergizing with the endogenous mediator TNFα.

Keywords: Bacteria, Cytokine Induction, Gene Expression, Inflammation, Leukocyte, NF-kappa B, p38 MAPK, Signal Transduction

Introduction

Leukocytes constitute the first line of host defense against invading microorganisms and are a major cellular component of the inflammatory reaction (1, 2). The recruitment of leukocytes to the site of inflammation and infection from the blood system is coordinated by a gradient of chemotactic factors/chemoattractants. The fMLP,3 derived from bacteria, was classically described as a chemoattractant and induces the chemotaxis of phagocytic leukocytes (3). Recent studies from our laboratory have found that bacterial fMLP activates NF-κB in leukocytes, with the signaling molecules being required for fMLP-induced inflammatory cytokine gene expression (4–10). Despite the importance of understanding the host response to bacterial infection, many of the fundamental molecular mechanisms of host-pathogen interactions remain unknown.

The pro-inflammatory cytokine such as TNFα is considered one of the key inflammatory mediators during bacterial infection. This powerful protein, secreted mostly by human blood leukocytes, such as monocytes/macrophages, acts as a host defense against bacterial infections. However, excessive elevations of TNFα can lead to inflammatory disorders (11). The regulation of gene expression in these cells is governed by the activities of transcription factors such as NF-κB, NF-IL-6, and AP-1. NF-κB is of paramount importance to immune cell function because of its ability to activate the transcription of many proinflammatory immediate-early genes (12, 13). NF-κB, which has been studied in great detail and shown to be dimeric in structure, is composed of members of the Rel family of transcriptional activators. In dormant cells, NF-κB is normally complexed with a member of the IκB proteins, which localizes the transcription factor to the cytosol in an inactive state (14). Stimulation of the cells with ligands such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), TNFα, and IL-1 results in the rapid dissociation of IκB and the subsequent entry of the active NF-κB to the nucleus where it can interact with DNA. Many kinases have been shown to phosphorylate IκB at specific N-terminal serine residues. The most well studied kinases are the IκB kinases (IKKs) IKKα, IKKβ, and IKKγ (15–17). Phosphorylation of IκB by the IKK pathway will eventually lead to the nuclear translocation of NF-κB, which in turn activates expression of target genes such as TNFα, IL-1, and IL-8 in the nucleus. Tremendous efforts have been made toward understanding how NF-κB is activated by various inducers, including bacteria, viruses, and cytokines. However, most research so far on NF-κB regulation has been focused on understanding how NF-κB is activated by a single inducer. This is unlike the situation in vivo where multiple inflammation inducers, including both exogenous and endogenous mediators, are present concurrently at the site of inflammation. Thus, an important question is raised as to whether mixtures of inflammation inducers would have a significant impact on host-pathogen interactions. Recently, studies from both our laboratory and other laboratories have shown that bacterial chemoattractant fMLP activates NF-κB by IKK-IκB and p38 MAPK signaling pathways (18–21). Therefore, we hypothesized that inflammatory responses are induced by multiple inducers from both exogenous and endogenous sources that operate synergistically by activating multiple signaling pathways and that this synergy is likely to play a significant role in the induction of host defense to bacterial infections and in the pathogenesis of inflammatory disorders.

Here, we report that fMLP and TNFα synergistically induce inflammatory response via multiple signaling pathways in vitro and in vivo. The mechanism of synergistic activation of NF-κB by bacterial fMLP and TNFα may involve the induction of RelA acetylation, which is regulated by p38 MAPK. Thus, this study provides direct evidence for the synergistic induction of NF-κB-dependent inflammatory responses by both exogenous and endogenous inducers. The ability of fMLP to synergize with TNFα and to activate NF-κB represents a novel and potentially important mechanism through which bacterial chemoattractant fMLP cannot only attract leukocytes but also directly contribute to inflammation by synergizing with endogenous mediator TNFα.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

fMLP was purchased from Sigma. Trichostatin A (TSA), TNFα antagonist (R-7050), and SB203580 were purchased from Calbiochem. Recombinant human TNFα was purchased from Invitrogen. Antibodies for phospho-p65 and phospho-p38 MAPK were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Oligonucleotides and their complementary strands for electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were from Promega (Madison, WI) and Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The sequence is 5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC-3′ (NF-κB).

Preparation of Monocytes from Human Peripheral Blood and Monocytic Cell Lines

Heparinized human peripheral blood from health donors was fractionated on Percoll (GE Healthcare) density gradients. Monocytes were prepared from the mononuclear cell population as described previously (22). The monocytic cell line THP-1 cells were differentiated by incubation with 1,25(OH)2D3 for 3 days (23). THP1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA) with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 units/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), l-glutamine (2 mm; Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA), and 2-mercaptoethanol (complete media).

Quantitative Real Time PCR Analysis of TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-8

Human peripheral blood monocytes were stimulated with fMLP and TNFα or fMLP/TNFα for 2 h. Total RNA was isolated by using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) by following the manufacturer's instructions. For the reverse transcription reaction, TaqMan reverse transcription reagents (Applied Biosystems) were used. The reverse transcription reaction was performed for 60 min at 37 °C, followed by 60 min at 42 °C by using oligo(dT) and random hexamers. PCR amplification was performed by using TaqMan Universal Master Mix. Predeveloped TaqMan assay reagents (probe and primer mixture of human TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-8) were used to detect expression of the gene. In brief, reactions were performed in duplicate containing 2× Universal Master Mix, 2 μl of template cDNA, 200 nm primers, and 100 nm probe in a final volume of 25 μl, and they were analyzed in a 96-well optical reaction plate (Applied Biosystems). Probes include a fluorescent reporter dye, 6-carboxyfluorescein, on the 5′ end and labeled with a fluorescent quencher dye, 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine, on the 3′ end to allow direct detection of the PCR product. Reactions were amplified and quantified by using an ABI 7500 sequence detector and the manufacturer's corresponding software (Applied Biosystems). Relative quantity of TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-8 mRNA was obtained by using the comparative Ct method (for details, see User Bulletin 2 for the ABI PRISM 7500 sequence-detection system) and was normalized by using predeveloped TaqMan assay reagent human cyclophilin as an endogenous control (Applied Biosystems).

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (4). Antibodies against RelA was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), and acetyl-lysine was from Upstate.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

Nuclear extracts were prepared from human peripheral blood monocytes using a modified method of Dignam et al. (24), and EMSAs were performed using 2.5 μg of the nuclear extract as described previously (25).

Luciferase Activity Assay

The reporter construct NF-κB-LUC was generated as described previously (26). Cells were co-transfected with 0.35 μg of NF-κB-luc and 0.05 μg of pRL-tk-null-luc (reporter gene) (Promega, Madison, WI) using Amaxa according to the manufacturer's protocol. The transfected cells were cultivated for 48 h before a 6-h incubation in medium ± fMLP, TNFα, or fMLP/TNFα. Luciferase activity was determined by using the luciferase assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI) and a Monolight 3010 luminometer (Analytical Luminescence, San Diego).

ELISA

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid or the media were from stimulated human peripheral blood monocytes (fMLP, TNFα, or fMLP/TNFα for 6 h). The fluid or media were collected, and the secreted TNFα was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using a commercial kit (Genzyme Corp.) according to the manufacturer's recommended protocol. The quantities of secreted TNFα in the test samples were determined by using a standard curve generated with purified TNFα.

Mouse and Animal Experiments

C3H/HeOuJ mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory, and all animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The Scripps Research Institute and Medical University of Ohio. Under anesthesia, mice were intranasally treated with fMLP (0.5 mg/kg) or TNFα (10 μg/kg) or fMLP plus TNFα in 50 μl of sterile PBS (control). BAL was performed by cannulating the trachea with sterilized PBS, and cells from BAL fluid were stained with Wright-Giemsa stain after cytocentrifuging. For TNFα protein release, BAL fluid was collected, and secreted TNFα was measured by ELISA as described above.

RESULTS

fMLP and TNFα Synergistically Induce NF-κB Activation and Inflammatory Cytokines Expression in Human Blood Monocytes and Macrophages

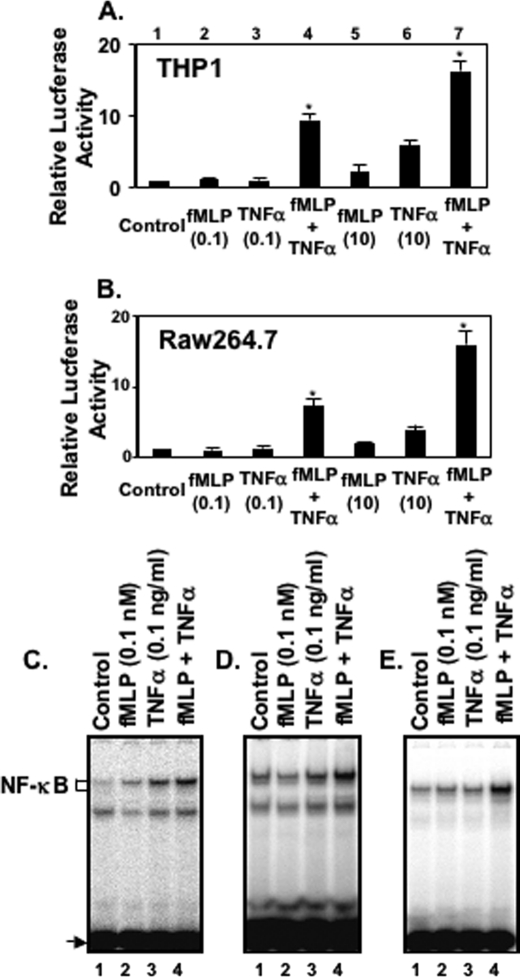

To determine whether fMLP and TNFα synergistically activate NF-κB in monocytes and macrophages, we first measured NF-κB-dependent promoter activity by using luciferase reporter plasmid in THP1 cells and RAW274.6 cells. As shown in Fig. 1, A and B, lanes 5 and 6, both 10 nm fMLP and 10 ng/ml TNFα (Fig. 1, A and B, lanes 5 and 6) caused enhanced expression of an NF-κB-controlled reporter gene in THP1 cells (Fig. 1A) and RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 1B), but they were ineffective when used at the lower concentrations of 0.1 nm and 0.1 ng/ml, respectively (Fig. 1, A and B, lanes 2 and 3). However, when THP1 cells or RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with 0.1 nm fMLP and 0.1 ng/ml TNFα together, significant NF-κB activation was seen (Fig. 1, A and B, lane 4). This experiment suggests that synergistic activation of leukocytes could occur at a low concentration of fMLP and TNFα. We then determined whether there was evidence for the synergy in the activation of NF-κB induced by fMLP and TNFα. As shown in Fig. 1, C–E, fMLP synergized with TNFα to activate NF-κB in human peripheral blood monocytes (Fig. 1C), THP1 cells (Fig. 1D), and RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 1E). This experiment suggests that synergistic induction of pro-inflammatory cytokine by fMLP and TNFα acts on the level of transcriptional activation.

FIGURE 1.

Bacterial chemoattractant fMLP and TNF-α synergistically activate NF-κB in human blood monocytes/macrophages. THP1 cells (A) and RAW264.7 cells (B) were transiently transfected with an NF-κB-regulated luciferase reporter construct and stimulated with medium (lane 1), 0.1 nm fMLP (lane 2), 0.1 ng/ml TNFα (lane 3), both 0.1 nm fMLP and 0.1 ng/ml TNFα (lane 4), 10 nm fMLP (lane 5), 10 ng/ml TNFα (lane 6), and both 10 nm fMLP and 10 ng/ml TNFα (lane 7) for 6 h. Luciferase activity was then assessed in treated and untreated cells. Synergistic induction of NF-κB DNA binding activity by fMLP and TNF-α was observed in a variety of monocytes and macrophages, including human peripheral blood monocytes (C), THP1 (D), and RAW264.7 cells (E). In all of the experiments shown, transfections were carried out in triplicate. Results shown are means ± S.E. from three separate measurements. Significance (p < 0.001), indicated by *, is fMLP + TNFα-stimulated cells versus fMLP-stimulated cells plus TNFα-stimulated cells.

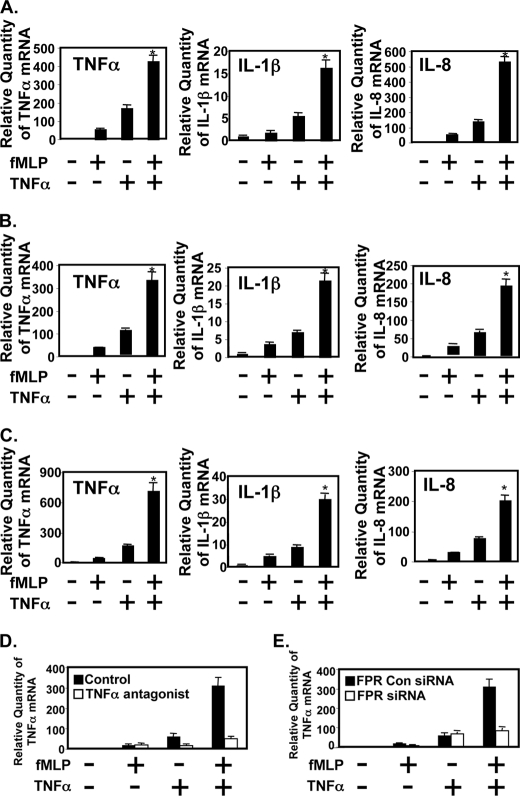

Because of the important role that NF-κB plays in regulating various key inflammatory mediators, we next sought to determine whether fMLP and TNFα also synergistically induce several key NF-κB-dependent inflammatory mediators, including TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-8, by performing real time quantitative PCR analysis to assay mRNA quantitatively and ELISA to detect protein level in monocytes and macrophages. We tested the effect of fMLP and TNFα on the expression of TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-8. As shown in Fig. 2, fMLP and TNFα synergistically induce expression of TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-8 in human monocytes (Fig. 2A), THP1 cells (Fig. 2B), and RAW274.6 cells (Fig. 2C). We then investigated the role of TNFα antagonist (R-7050, Calbiochem) in synergistic induction of cytokine induction in THP1 cells. TNFα antagonist significantly blocked TNFα-induced cytokine expression and synergistic induction of cytokine by fMLP and TNFα (Fig. 2D). Consistent with these results, synergistic induction of TNFα was not observed in fMLP receptor knockdown cells as compared with control cells (Fig. 2E). These data suggest that synergistic expression of cytokine by fMLP and TNFα appears to involve signaling via both fMLP receptor and TNFα receptor.

FIGURE 2.

fMLP and TNF-α synergistically induce expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8 in human peripheral blood monocytes (A), THP1 (B), and RAW264.7 (C) cells as assessed by performing real time quantitative PCR analysis. D, synergistic induction of inflammation by fMLP and TNFα is TNFα receptor-dependent. THP1 cells were pretreated with 2 μm of TNFα antagonist (R-7050, Calbiochem) and then stimulated with fMLP, TNFα, or fMLP plus TNFα. Total RNA was extracted and reverse-transcribed, and the cDNA was amplified with human TNFα primers by real time PCR. E, fMLP receptor is required for synergistic induction of TNFα by fMLP and TNFα. THP1 cells were transfected with siRNA fMLP receptor or control siRNA. Thirty hours post-transfection, they were stimulated with fMLP, TNFα, or fMLP plus TNFα. Total RNA was extracted, and the cDNA was amplified with human TNFα primers by real time PCR. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Significance (p < 0.001), indicated by *, is fMLP + TNFα-stimulated cells versus fMLP-stimulated cells plus TNFα-stimulated cells.

Collectively, these results indicate that bacterial chemoattractant fMLP and endogenous mediator TNFα synergistically stimulate inflammatory cytokine production in blood monocytes and tissue macrophages. The effects of mixtures of multiple pathogenic factors are more relevant to the in vivo situation occurring during a bacterial infection than the effects of a single inducer.

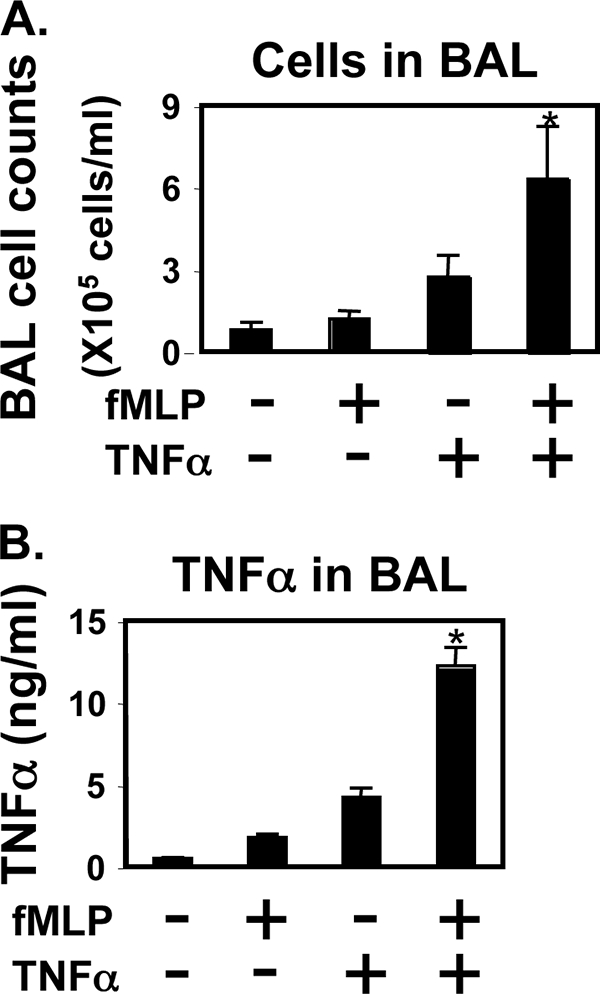

fMLP and TNFα Synergistically Induce Inflammatory Response in Vivo

We next determined whether fMLP and TNFα synergistically induce lung inflammatory responses in mice. Mice were treated with fMLP (0.5 mg/kg) and TNFα (10 μg/kg), which were administered intranasally in 50 μl of sterile PBS. After 1 day, BAL fluid was assessed for infiltrating cells (Fig. 3A), and proinflammatory cytokines (Fig. 3B) were examined by ELISA. Mice exposure to mixture of fMLP and TNFα had significantly more infiltrating cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids than did the mice stimulated with either fMLP or TNFα alone. There was also a dramatic and significant increase in the amount of cytokines produced in BAL fluid when mice received mixtures of fMLP and TNFα rather than fMLP or TNFα alone (Fig. 3B). Consistent with these in vivo results, it demonstrates that fMLP and TNFα synergistically induce inflammatory response in vitro and in the murine model of lung inflammation.

FIGURE 3.

Synergistic induction of inflammation by chemoattractant fMLP and TNFα in the murine model of lung inflammation. C3H/HeOuJ mice were treated intranasally with either fMLP (0.5 mg/kg) or TNFα (10 μg/kg) or fMLP plus TNFα in 50 μl of sterile PBS. One day after the challenge, mice were sacrificed, and the BAL fluid was assessed for the presence of cellular infiltrates by cell counting (A) and TNFα ELISA (B). Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. of three different experiments, and each had five mice per group. Significance (p < 0.001), indicated by *, is fMLP + TNFα-challenged animals versus fMLP-challenged animals plus TNFα-challenged animals.

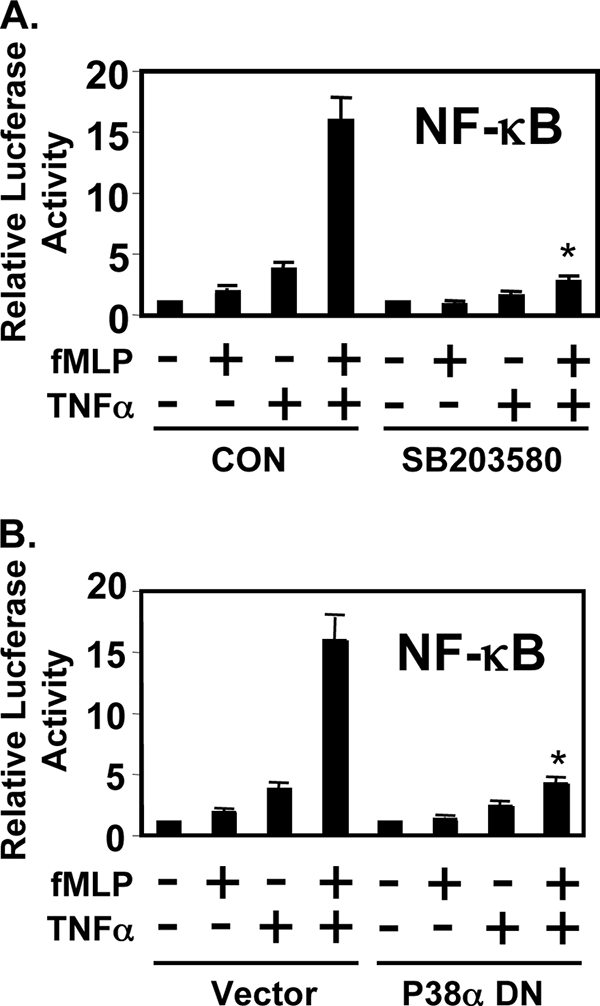

Activation of p38 MAPK Pathway Is Required for the Synergistic Activation of NF-κB by fMLP and TNFα

Many cellular stress stimuli can activate both NF-κB and p38 MAPK molecules (27–31). Because of this overlap, we explored the possibility that activation of p38 is also involved in the synergistic NF-κB activation. We first sought to determine whether activation of p38 MAPK is required for the synergistic NF-κB activation by assessing the effect of SB203580, a specific inhibitor for p38 MAPK (32). As shown in Fig. 4A, SB203580 abrogates the synergistic activation of NF-κB in response to fMLP and TNFα. Moreover, overexpression of a dominant-negative mutant form of p38 inhibits the synergistic NF-κB activation as well, confirming the involvement of p38 MAPK in the synergistic NF-κB activation (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that p38 MAPK is also involved in the synergistic activation of NF-κB induced by fMLP and TNFα.

FIGURE 4.

Activation of p38 MAPK pathway is required for the synergistic activation of NF-κB by fMLP and TNF-α. A, SB203580 inhibited the synergistic activation of NF-κB by fMLP and TNF-α. CON, control. B, overexpression of dominant-negative (DN) mutants of p38α inhibited synergistic activation of NF-κB in THP1 cells. Values are means ± S.D. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

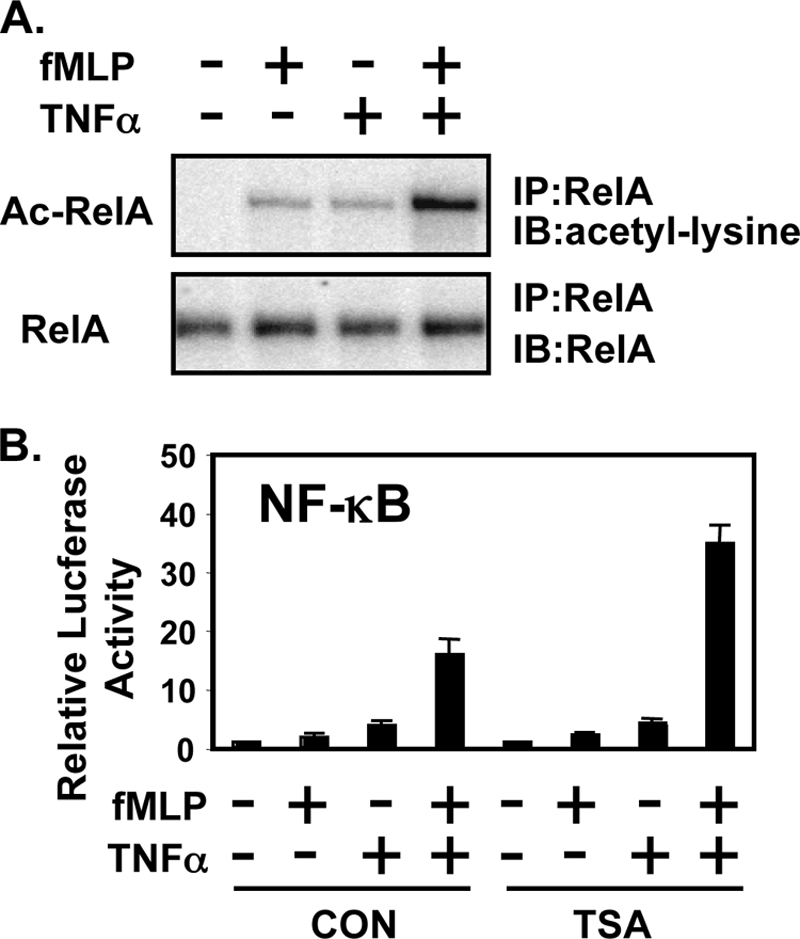

Synergistic Activation of NF-κB by fMLP and TNF-α via Induction of RelA Acetylation

Recently, acetylation of RelA has been shown to play critical roles in NF-κB activation by enhancing the DNA binding activity of RelA to the κB site (33–35). Thus, we hypothesized that acetylation of RelA may be involved in mediating the synergy by fMLP and TNF-α. To test our hypothesis, we first assessed RelA acetylation. Interestingly, acetylation of RelA is synergistically induced by fMLP and TNF-α (Fig. 5A). Because acetylation of RelA plays an important role in NF-κB activation by enhancing the DNA binding activity of RelA to the κB site (33–35), we next investigated the effect of TSA, an inhibitor of histone deacetylase, on NF-κB activation induced by TNF-α and fMLP. As shown, TSA treatment further enhanced the synergistic activation of NF-κB induced by TNF-α and fMLP (Fig. 5B). Taken together, we concluded from these results that fMLP synergistically enhances TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation via induction of RelA acetylation.

FIGURE 5.

fMLP synergistically enhances TNF-α-induced NF-κB DNA-binding activity via induction of RelA acetylation. A, fMLP synergistically enhances TNF-α-induced RelA acetylation. Acetylation of RelA was detected by immunoblotting (IB) the anti-RelA (α-RelA) immunoprecipitates (IP) with anti-acetylated lysine antibodies (upper panel). Relative RelA acetylation (Ac-RelA/total RelA) of TNF-α treatment with or without fMLP compared with control treatment was quantified from three independent experiments (lower panel). B, TSA, an inhibitor of histone deacetylase, further enhanced synergistic NF-κB activation induced by TNF-α and fMLP. Values are means ± S.D. (n = 3). Results are representative of three or more independent experiments. CON, control.

Synergistic Induction of RelA Acetylation and NF-κB Activation by fMLP and TNF-α Is Mediated by p38 MAPK

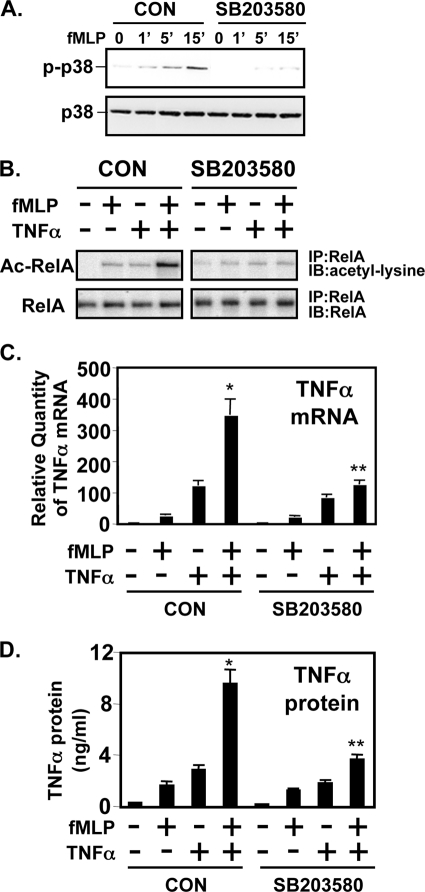

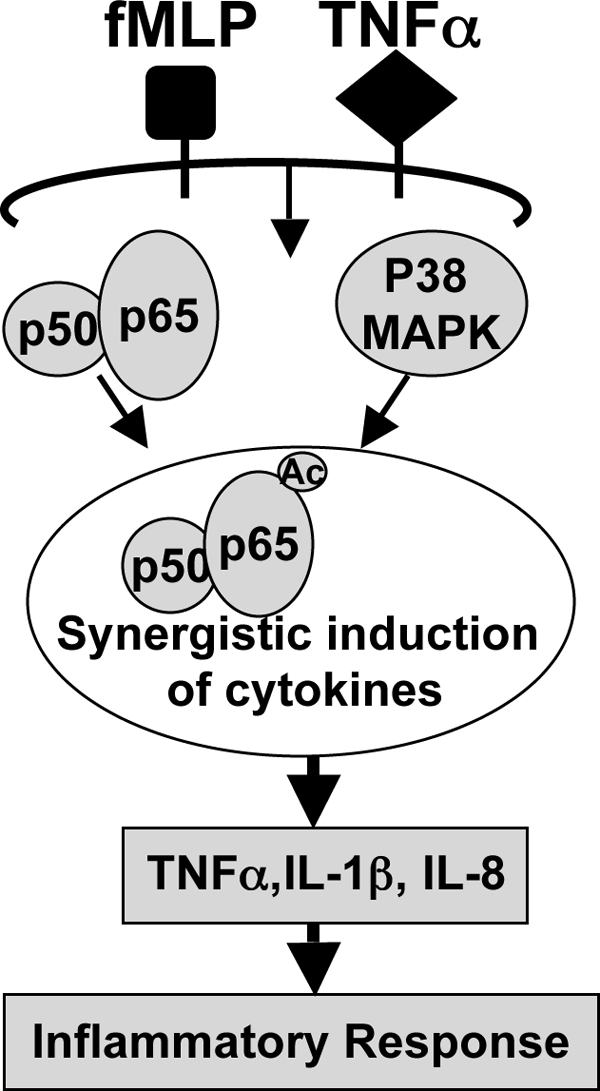

To determine the possible involvement of p38 MAPK in RelA acetylation, we first evaluated the effect of SB203580 on fMLP-induced p38 phosphorylation in THP1 cells. As shown in Fig. 6A, SB203580 inhibits fMLP-induced p38 phosphorylation in THP1 cells. We then evaluated the effect of SB203580 on RelA acetylation. Fig. 6B shows synergistic RelA acetylation by TNF-α, and fMLP was attenuated by SB203580 treatment. Moreover, SB203580 also greatly inhibited synergistic enhancement of inflammatory cytokine TNFα expression induced by fMLP and TNFα as assessed by Q-PCR (Fig. 6C) and by ELISA (Fig. 6D). Thus, these results suggest that p38 MAPK is involved in synergistic activation of NF-κB by fMLP and TNF-α through p38 MAPK-mediated RelA acetylation (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 6.

Synergistic induction of RelA acetylation and NF-κB activation by fMLP and TNF-α is mediated by p38 MAPK. A, SB203580 inhibits fMLP-induced p38 phosphorylation. B, synergistic RelA acetylation by fMLP and TNF-α was inhibited by SB203580. CON, control (no inhibitor). Synergistic expression of TNFα mRNA (C) and protein (D) by TNF-α and fMLP was also blocked by SB203580 in THP1 cells. CON, control (no inhibitor). Values are means ± S.D. (n = 3). Results are representative of three or more independent experiments. IP, immunoprecipitated; WB, Western blot.

FIGURE 7.

Schematic representation of synergistic NF-κB activation by fMLP and TNFα via p38 MAPK-dependent RelA acetylation in monocytes and macrophages.

DISCUSSION

Viable bacteria in infected tissue have been observed to attract leukocytes. fMLP was purified and identified as the major peptide from both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria (36, 37). Stimulation of leukocytes with fMLP induced several cellular functions, including directed cell movement, phagocytosis, and the generation of reactive oxygen intermediates (38). Recently, we found that fMLP activates NF-κB in monocytes and macrophages, thereby stimulating the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNFα, IL-1, and IL-8.

In the host immune system, the leukocytes are often exposed to multiple pathogens, including both exogenous and endogenous sources. Under in vivo situations such as bacterial infection, little is known about the host response to bacterial infection. Many of the fundamental molecular mechanisms of host-pathogen interactions remain unknown. In this study, we showed that mixtures of bacterial chemoattractant fMLP and key inflammatory mediator TNFα behave synergistically in the activation of NF-κB and in the induction of inflammation in vitro and in vivo.

These results demonstrate an important role for bacterial chemoattractant fMLP from exogenous bacteria and key inflammatory cytokine TNFα from endogenous mediators in the pathogenesis of bacterial infections. The most current studies on inflammatory regulation in bacterial infections have focused primarily on the induction of inflammation by a single pathogenic inducer and not by mixtures. Although studies with a single pathogenic inducer are indeed critical for our understanding of the molecular basis of the relevant signaling pathway, the information derived may be insufficient for a full understanding of how inflammation is induced in vivo where both exogenous and endogenous mediators are present simultaneously. In the pathogenesis of bacterial infections, fMLP first interacts with its receptors sitting on the surface of host leukocytes, which, in turn, leads to the up-regulation of genes encoding important inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα. The up-regulated TNFα in response to fMLP will in turn act on the host cells and synergize with fMLP to further induce inflammatory cytokines. Therefore, the signaling mechanisms underlying bacteria-induced inflammation in the presence of both exogenous and endogenous inducers appear to be more complicated than the signaling mechanisms underlying bacteria-induced inflammation in the presence of a single inducer.

In this study, we found that fMLP, a bacterial chemoattractant, synergizes with TNFα, a key proinflammatory cytokine, to activate NF-κB in a synergistic manner both in vitro and in vivo. The ability of fMLP to synergize with TNFα and activate NF-κB represents a novel and potentially important mechanism through which bacterial fMLP not only attracts leukocytes but also directly contributes to inflammation by synergizing with the endogenous mediator TNFα. The control of inflammation is likely to best be understood on the level of this synergistic regulation. These results represent an important pathogenic phenomenon, which is not fully understood in bacterial infection. This study has significantly expanded and enhanced our understanding of how inflammation is induced in vivo where multiple inducers, including both exogenous and endogenous sources, are present simultaneously. There is very limited information currently available concerning the synergistic activation of inflammation. A better understanding could bring new insights into the regulation of inflammation and may suggest novel therapeutic strategies or targets to minimize host injury following bacterial infection.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant AI43524 from USPHS and Grant M01RR00833 (to General Clinical Research Center, Scripps Research Institute). This work was also supported in part by the Sam and Ross Stein Charitable Trust.

- fMLP

- f-Met-Leu-Phe

- MAP

- mitogen-activated protein

- IKK

- IκB kinase

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor κB

- QRT

- quantitative real time

- TSA

- trichostatin A

- BAL

- bronchoalveolar lavage.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen R. A., Jekaitis A. J., Cochrane C. G. (1990) in Cellular and Molecular Mechanism of Inflammation (Cochrane C. G., Gimbrone J. A. eds) pp. 83–106, Academic Press, San Diego [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snyderman R., Uhlig R. J. (1988) in Inflammation: Basic Principles and Clinical Correlates (Gallin J. I., Goldstein I. M., Snyderman R. eds) pp. 309–348, Raven Press, Ltd., New York [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy P. M. (1994) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 12, 593–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan Z. K., Chen L. Y., Cochrane C. G., Zuraw B. L. (2000) J. Immunol. 164, 404–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang S., Chen L. Y., Zuraw B. L., Ye R. D., Pan Z. K. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 40977–40981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen L. Y., Zuraw B. L., Ye R. D., Pan Z. K. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 7208–7212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L. Y., Ptasznik A., Pan Z. K. (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 319, 629–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen L. Y., Doerner A., Lehmann P. F., Huang S., Zhong G., Pan Z. K. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 22497–22501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen L. Y., Pan W. W., Chen M., Li J. D., Liu W., Chen G., Huang S., Papadimos T. J., Pan Z. K. (2009) J. Immunol. 182, 2518–2524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen L. Y., Pan Z. K. (2009) Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 9, 361–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bazzoni F., Beutler B. (1996) N. Engl. J. Med. 334, 1717–1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sen R., Baltimore D. (1986) Cell 46, 705–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baeuerle P. A., Henkel T. (1994) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 32, 141–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baeuerle P. A., Baltimore D. (1988) Science 242, 540–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatada E. N., Krappmann D., Scheidereit C. (2000) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 12, 52–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Q., Verma I. M. (2002) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 725–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghosh S., Karin M. (2002) Cell 109, S81–S96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ayala J. M., Goyal S., Liverton N. J., Claremon D. A., O'Keefe S. J., Hanlon W. A. (2000) J. Leukocyte Biol. 67, 869–875 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zu Y. L., Qi J., Gilchrist A., Fernandez G. A., Vazquez-Abad D., Kreutzer D. L., Huang C. K., Sha'afi R. I. (1998) J. Immunol. 160, 1982–1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nick J. A., Avdi N. J., Young S. K., Knall C., Gerwins P., Johnson G. L., Worthen G. S. (1997) J. Clin. Invest. 99, 975–986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan Z., Kravchenko V. V., Ye R. D. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 7787–7790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schiff D. E., Kline L., Soldau K., Lee J. D., Pugin J., Tobias P. S., Ulevitch R. J. (1997) J. Leukocyte Biol. 62, 786–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Browning D. D., Pan Z. K., Prossnitz E. R., Ye R. D. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 7995–8001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dignam J. D., Lebovitz R. M., Roeder R. G. (1983) Nucleic Acids Res. 11, 1475–1489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan Z. K., Zuraw B. L., Lung C. C., Prossnitz E. R., Browning D. D., Ye R. D. (1996) J. Clin. Invest. 98, 2042–2049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shuto T., Xu H., Wang B., Han J., Kai H., Gu X. X., Murphy T. F., Lim D. J., Li J. D. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 8774–8779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schulze-Osthoff K., Ferrari D., Riehemann K., Wesselborg S. (1997) Immunobiology 198, 35–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ono K., Han J. (2000) Cell. Signal. 12, 1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mercurio F., Manning A. M. (1999) Oncogene 18, 6163–6171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wesselborg S., Bauer M. K., Vogt M., Schmitz M. L., Schulze-Osthoff K. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 12422–12429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J. D., Feng W., Gallup M., Kim J. H., Gum J., Kim Y., Basbaum C. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 5718–5723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adams J. L., Lee D. (1999) Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Dev. 2, 96–109 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen L. f., Fischle W., Verdin E., Greene W. C. (2001) Science 293, 1653–1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen L. F., Mu Y., Greene W. C. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 6539–6548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen L. F., Williams S. A., Mu Y., Nakano H., Duerr J. M., Buckbinder L., Greene W. C. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 7966–7975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marasco W. A., Phan S. H., Krutzsch H., Showell H. J., Feltner D. E., Nairn R., Becker E. L., Ward P. A. (1984) J. Biol. Chem. 259, 5430–5439 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rot A., Henderson L. E., Copeland T. D., Leonard E. J. (1987) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 7967–7971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Truett A. P., 3rd, Verghese M. W., Dillon S. B., Snyderman R. (1988) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 1549–1553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]