Abstract

Cdc25B is a key regulator of entry into mitosis, and its activity and localization are regulated by binding of the 14-3-3 dimer. There are three 14-3-3 binding sites on Cdc25B, with Ser323 being the highest affinity binding and is highly homologous to the Ser216 14-3-3 binding site on Cdc25C. Loss of 14-3-3 binding to Ser323 increases cyclin/Cdk substrate access to the catalytic site, thereby increasing its activity. It also affects the localization of Cdc25B. Thus, phosphorylation and 14-3-3 binding to this site is essential for down-regulating Cdc25B activity, blocking its mitosis promoting function. The question of how this inhibitory signal is relieved to allow Cdc25B activation and entry into mitosis is yet to be resolved. Here, we show that Ser323 phosphorylation is maintained into mitosis, but phosphorylation of Ser321 disrupts 14-3-3 binding to Ser323, mimicking the effect of inhibiting Ser323 phosphorylation on both Cdc25B activity and localization. The unphosphorylated Ser321 appears to have a role in stabilizing 14-3-3 binding to Ser323, and loss of the Ser hydroxyl group appears to be sufficient to significantly reduce 14-3-3 binding. A consequence of loss of 14-3-3 binding is dephosphorylation of Ser323. Ser321 is phosphorylated in mitosis by Cdk1. The mitotic phosphorylation of Ser321 acts to maintain full activation of Cdc25B by disrupting 14-3-3 binding to Ser323 and enhancing the dephosphorylation of Ser323 to block 14-3-3 binding to this site.

Keywords: CDK (Cyclin-dependent Kinase), Cell Cycle, Dual Specificity Phosphoprotein Phosphatase, Mitosis, Site-directed Mutagenesis, 14-3-3, Cdc25B

Introduction

The Cdc25B isoform is a dual-specificity phosphate, which is proposed to function as an initiator of entry into mitosis (1, 2) The phosphatase activates its substrates cyclin/Cdks by dephosphorylating inhibitory residues on the Cdk subunits at Thr14 and Tyr15, which drives entry into mitosis (1, 3, 4). The phosphatase also activates cyclin A/Cdk2 in the early G2 phase (5). Five splicing variants of Cdc25B have been reported, two of which B2 and B3 are expressed at detectable protein levels (6, 7).

Cdc25B is regulated by multiple mechanisms, including its expression, stability, localization, and its interaction with 14-3-3 adapter proteins. Cdc25B protein levels increase in G2 phase and peak in metaphase, prior to its degradation upon mitotic exit (1). The proteasome-mediated degradation of Cdc25B has been reported to be triggered by phosphorylation by cyclin A/Cdk1 (8). Recently, we found that Cdc25B also was destabilized in response to MAPK activation (9), whereas another study reported on the degradation of Cdc25B, which is dependent on c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) or p38MAPK (10).

Three 14-3-3 binding sites exist on human Cdc25B, Ser323, Ser230, and Ser151, with Ser323 being the highest affinity binding site (11–13). Different isoforms of 14-3-3 have different preferred binding sites on Cdc25B. 14-3-3β and -ϵ bind preferentially to Ser323, whereas 14-3-3σ prefers Ser230 (13). We have proposed previously that the 14-3-3 dimer forms an intramolecular bridge connecting the N- and C-terminal domains of Cdc25B, regulating cyclin/Cdk substrate access to the catalytic site, thereby regulating Cdc25B. 14-3-3 binding to the Ser323 site also appears to affect access to the proximal nuclear localization sequence, whereas binding to the Ser151 and Ser230 site affects access to the proximal nuclear export sequence (12). Thus, loss of binding to any site was sufficient to increase Cdc25B activity by increasing substrate access to the catalytic site, but had quite different effects on localization.

Previous studies on Cdc25B have been carried out using either wild type or catalytically inactive substrate trapping mutants of Cdc25B. Overexpression of these proteins limits the investigation of Cdc25B during G2/M progression, as overexpression of the wild type Cdc25B promotes premature entry into mitosis, whereas overexpression of the inactive mutants cause G2 phase arrest (1, 11, 14). In this study, we have produced an inert form of Cdc25B by mutating the substrate binding sites, to allow us to examine its 14-3-3 binding and localization without perturbing the cell cycle. Tyr511 (using Cdc25B3 numbering) was identified as a critical substrate binding site residue, and its mutation has been reported to reduce the activity of Cdc25B to <0.5% compared with wild type Cdc25B, without altering the active site (15, 16).

The sequence around the Ser323 site in Cdc25B RSPS323MP is identical to the human Cdc25C Ser216 region the primary 14-3-3 binding on Cdc25C. A previous study had identified phosphorylation of Ser214 on Cdc25C by Cdk1 in mitosis and reported that phosphorylation of Ser214 blocked 14-3-3 binding to the Ser216 site (17). As these regions in Cdc25B and Cdc25C are identical, we reasoned that these residues would likely perform a similar role in regulating Cdc25B activity. Here, we have examined the effect of mutation of Ser321 on 14-3-3 binding to Cdc25B3 Ser323 and phosphorylation and the localization and activity of Cdc25B3.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture, Synchrony, and Transfection

HeLa and HeLa-Bcl2 cells were grown in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% Serum Supreme (BioWhittaker). U2OS cells stably expressing HA-tagged Cdc25B (HA-Cdc25B) under the control of a tetracycline-suppressible promoter (18) were maintained in 10% fetal bovine serum containing medium with 2 μg/ml tetracycline to suppress Cdc25B expression. All cell lines were maintained in a 5% CO2-humidified incubator at 37 °C. Single and double thymidine block/release synchronies were performed as described previously (19). Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunoblotting and Immunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed in 14-3-3 lysis buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 7.8, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgSO4, 5 mm DTT, and 0.1% Triton X-100) supplemented with 5 μg/ml leupeptin, pepstatin A, aprotinin, 1 mm PMSF, 25 mm NaF, 0.1 mm sodium orthovanadate, and 25 mm β-glycerophosphate. The cleared supernatant was used for either immunoblotting or immunoprecipitated overnight at 4 °C with anti-Cdc25B antibody (C-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The antibody complexes were precipitated with 50 μl of 50% slurry of protein A-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences), washed three times with 14-3-3 lysis buffer, and eluted with SDS sample buffer. Samples were resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and immunoblotted with antibodies against Cdc25B, 14-3-3β, -σ, or -ϵ (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Myc tag (Cell Signaling), cyclin A (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), cyclin B (1), pTyr15 Cdk1 and phospho-Ser216 Cdc25C (Cell Signaling), phospho-Ser323 Cdc25B (20), and detected using ECL (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). The phospho-Cdc25B and phospho-Cdc25C antibodies both detected the phosphorylation of Ser323 on Cdc25B and were used interchangeably through this work.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Transfected HeLa cells were grown on glass coverslips for immunofluorescence microscopy. Cells were washed once with PBS and fixed with −20 °C methanol and stored at −20 °C until required. For immunostaining, cells were washed with PBS, blocked with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 and 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS, and then incubated with primary antibody against α-tubulin (Sigma Aldrich) for 1 h at room temperature. Coverslips were washed and incubated with Alexa555-conjugated secondary antibody (Cell Signaling), and DNA was stained with 10 μg/ml DAPI. Coverslips were washed again as above and mounted onto microscope slides using Prolong® Gold antifade reagent.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

The PCR site-directed mutagenesis was conducted according to Stratagene's protocol. The following primers were designed to obtain the desired mutations: Y511A, 5′-CCGTGCTGTCAACGACGCCCCCAGCCTCTACTACCC-3′; S321A, 5′-CGGCTCTTCCGCGCCCCGTCCATGCCCTGC-3′; and S321D, 5′-CGGCTCTTCCGCGACCCGTCCATGCCCTGC-3′. The mutations are underlined and were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The substrate trapping and 14-3-3 binding site mutants were reported previously (1, 12).

Live Cell Time-lapse Microscopy

Time-lapse movies were produced using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 m Cell Observer with a 37 °C incubator hood and 5% CO2 cover. Digital images were taken every 10–15 min with a Zeiss AxioCam using 10× or 20× objectives under transmission and/or a 488-nm filter setting. The images were processed using AxioVision software (version 4.6). Cumulative mitotic cell counts were performed by following transfected or nontransfected cells in four or five random fields over several hours. The time at which cells entered mitosis was recorded for each cell in the field. The fields were combined and reported as a percentage of the total number of cells in the field at the start of the experiments. The data presented are typical of at least three independent experiments.

RESULTS

Substrate Binding Mutant of Cdc25B Is Tolerated by Cells

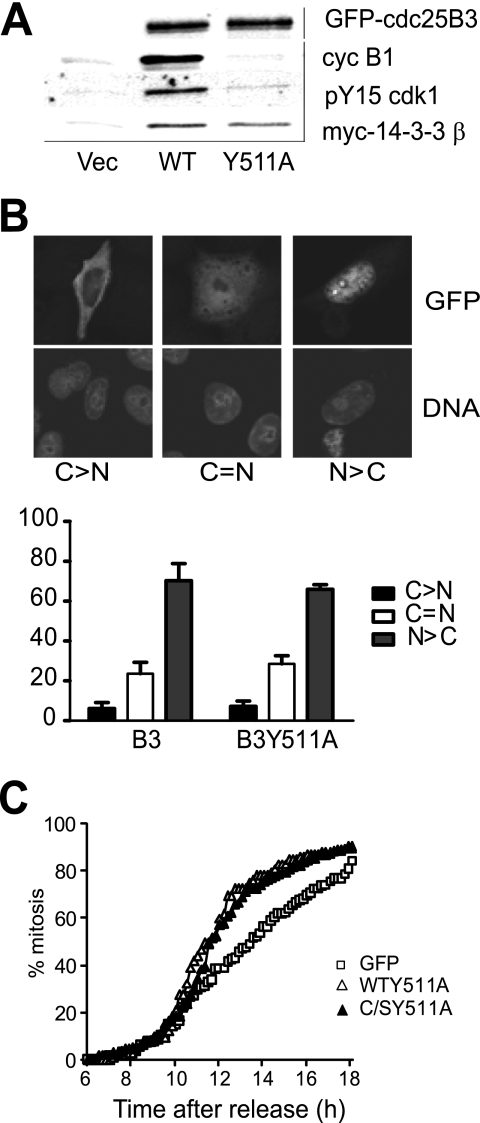

A substrate binding mutant of Cdc25B was produced to permit high level protein expression without altering cell cycle progression. This mutant was produced by mutating the substrate binding site Tyr511 of GFP-tagged Cdc25B3 into Ala, producing GFP-Cdc25B3 Y511A. The effect of expression of this mutation on cell cycle progression, interaction with substrate cyclin/Cdks, and its regulation by 14-3-3 proteins and localization was examined. The mutant Cdc25B had severely reduced substrate binding. This was clearly demonstrated with the substrate trapping mutant of Cdc25B3, where the substrate binding Y511A mutation was introduced, Cdk1 phosphorylated at Tyr15 (pTyr15) and its major cyclin partner cyclin B1 was reduced by >90% (Fig. 1A). The mutant retained its ability to interact with 14-3-3 proteins, shown here by interaction with the overexpressed Myc-tagged 14-3-3β (Fig. 1A). Examination of localization of Cdc25B3 substrate binding mutant revealed no significant difference from wild type Cdc25B3 8 h after transfection (Fig. 1B). When HeLa cells were transfected with substrate binding mutants of Cdc25B, synchronized at G1/S by thymidine block/release and followed using time-lapse microscopy, cells expressing the substrate binding mutant progressed into mitosis with similar kinetics to GFP-overexpressing cells (Fig. 1C). Indeed, the substrate binding mutant, either wild type for the catalytic residues or the inactive catalytic C487S mutants displayed identical kinetics, providing further evidence that this mutant lacks catalytic activity. This demonstrated that the substrate binding mutant proteins had no effect on G2/M progression over expression of GFP alone. This finding confirms the notion that Y511A mutation produced an inert form of Cdc25B, which behaved identically to the wild type protein in terms of 14-3-3 binding and localization although it has no effect on G2/M progression.

FIGURE 1.

The substrate binding mutant of Cdc25B had no effect on 14-3-3 binding, localization, or G2/M progression. A, substrate trapping mutants of GFP-Cdc25B3 C487S/R493K, either wild type for the substrate binding site residues (WT) or Y511A mutant, were transfected into HeLa cells followed by etoposide addition overnight to arrest cells in G2 phase. The interaction with substrate cyclin B1 and the inactive pTyr15 Cdk1, and exogenously expressed Myc-14-3-3β were examined from the immunoprecipitates of GFP-Cdc25B. Immunoprecipitation from cells expressing GFP alone (Vec) was performed as a control. B, HeLa cells were transfected with Cdc25B3 wild type (WT) and the substrate binding mutant Cdc25B3 Y511A. The localization was examined 8 h post-transfection. The different localization of GFP-Cdc25B3 relative to the nucleus is shown in the inset, with predominantly cytoplasmic localization (C > N), equivalent nuclear and cytoplasmic staining (C=N) and predominantly nuclear staining (N > C). The data represent three independent experiments counting a minimum of 200 transfected cells. C, HeLa cells were either transfected with the substrate binding mutants GFP-Cdc25B3 Y511A or GFP-Cdc25B2 Y511A (C/SY511A), which also incorporated the inactivating active site mutation, or GFP alone, synchronized at G1/S transition by thymidine synchrony, and the entry into mitosis was monitored by time lapse microscopy.

Mutation of Ser321 Reduces 14-3-3 Binding and Phosphorylation on Ser323

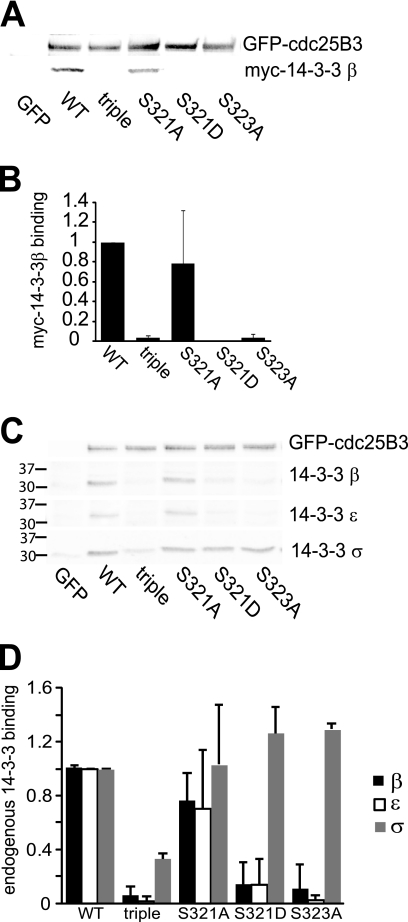

To evaluate the effect of Ser321 phosphorylation on the ability of 14-3-3 to bind to the high affinity site Ser323, and phosphorylation of Ser323, Ser321 was mutated to nonphosphorylatable Ala (S321A) and phosphomimetic Asp (S321D). These mutants were constructed in the substrate binding mutant of GFP-Cdc25B3, thereby allowing examination during G2/M phase. HeLa cells were transfected with either the Ser321 wild type, S321A, or S321D mutants, S323A, 14-3-3 binding site S151A/S230A/S323A triple mutants, or GFP, synchronized and harvested as they progressed through G2 phase. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated for GFP-Cdc25B and blotted for the interaction with exogenously expressed Myc-14-3-3β. The S321D mutation essentially abolished Myc-14-3-3β binding and was identical to the 14-3-3 binding site S323A mutant (Fig. 2, A and B). The effect of the S321A mutation was highly variable, although there was an overall trend to reduced 14-3-3 binding. The variability was only found with this mutant, all the others had consistent effects on 14-3-3 binding.

FIGURE 2.

Ser321 mutation reduces 14-3-3 binding. HeLa cells were co-transfected with the substrate binding site mutant of GFP-Cdc25B3 Y511A, either wild type for Ser321 (WT), S321A, S321D, S151A/S230A/S323A 14-3-3 binding sites triple mutants, or the S323A mutant, together with Myc-14-3-3β. The cells were synchronized and collected as they transited G2 phase, 7 h after synchrony release. The GFP-Cdc25B was immunoprecipitated and analyzed for Myc-14-3-3β binding, and the level of GFP-Cdc25B was analyzed by immunoblotting. GFP-transfected cells were used as controls. B, quantification of Myc-14-3-3β binding in A. 14-3-3 binding was normalized for GFP-Cdc25B levels in the immunoprecipitate from three independent experiments. C, similar experiment as in A but detecting endogenous 14-3-3β, -ϵ, and -σ binding. The position of the molecular weight markers for the 14-3-3 blots is shown for each isoform. D, quantification of endogenous 14-3-3 binding in C from three independent experiments.

The interaction of overexpressed GFP-Cdc25B3 mutants with endogenous β, ϵ, and σ, the preferred 14-3-3 isoforms for Cdc25B (13), was examined. The interaction with endogenous 14-3-3β was essentially identical to the exogenous Myc-14-3-3β binding, with the S321D mutant behaving similarly to the S323A mutant. 14-3-3ϵ binding was similarly reduced in both the S321D and S323A mutants (Fig. 2, C and D). Interestingly, 14-3-3β and -ϵ binding to the S321A mutant was again highly variable, which contrasted strongly with the highly consistent reduction seen with the S321D mutant. The binding of 14-3-3σ was unaffected by any of these mutations, although it was strongly reduced in the 14-3-3 binding site triple mutant. The selective effect on the binding of 14-3-3β and 14-3-3ϵ but not 14-3-3σ is an example of the site specificity of 14-3-3 isoform binding. 14-3-3σ has been found to preferentially interact with Ser230 Cdc25B, whereas 14-3-3β and 14-3-3ϵ bind the Ser323 site (13).

To examine the consequences of Ser321 mutation on the phosphorylation on Ser323, immunoprecipitated GFP-Cdc25B Ser321 mutants were immunoblotted with a phosphosite-specific antibody for Ser323. Ser323 phosphorylation was detected on the Ser321 wild type protein, but staining was lost in the S323A mutant, demonstrating antibody specificity (Fig. 3). The S321A and S321D mutations blocked Ser323 phosphorylation (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Ser321 mutation reduces Ser323 phosphorylation. HeLa cells were transfected with substrate binding site mutants of GFP-Cdc25B3 as in Fig. 2 and synchronized and harvested in G2 phase. The GFP-Cdc25B was immunoprecipitated and analyzed for Ser323 phosphorylation (pS323) and GFP-Cdc25B3 levels. Controls were untransfected (con) and GFP-transfected cells.

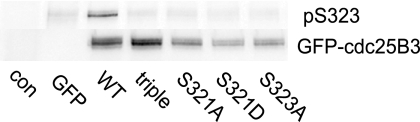

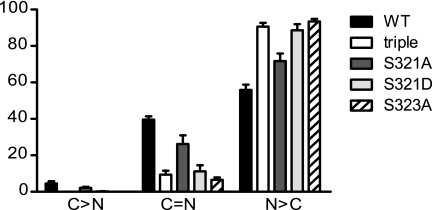

Ser321 Mutation Alters Cdc25B Localization

The effect of Ser321 mutation on the subcellular localization of Cdc25B was examined. HeLa cells were transfected with the substrate binding site mutant of GFP-Cdc25B wild type and S321A and Asp and 14-3-3 triple mutants, and the localization of the GFP-tagged proteins was investigated by immunofluorescence microscopy. In >90% of cells, S321D mutant accumulated in the nucleus, similar to the S323A mutant and triple mutants, whereas >80% of the S321A mutant localized to the nucleus, with an equivalent increase in the nuclear and cytoplasmic localization. The wild type version had a further reduction in the nuclear localization, to 60%, with increase nuclear and cytoplasmic localization (Fig. 4). Thus the S321A mutant was again an intermediate phenotype between the Ser321 Asp and wild type.

FIGURE 4.

Ser321 mutation increases nuclear localization of Cdc25B. HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated substrate binding site mutants of Cdc25B3, and their localization was examined by immunofluorescence 8 h post-transfection. The localization of the GFP-Cdc25B constructs expressed was quantitated as in Fig. 1B. The data are from three independent experiments counting at least 200 GFP-Cdc25B-expressing cells. C > N, predominantly cytoplasmic localization; C=N, equivalent nuclear and cytoplasmic staining, and N > C, predominantly nuclear staining.

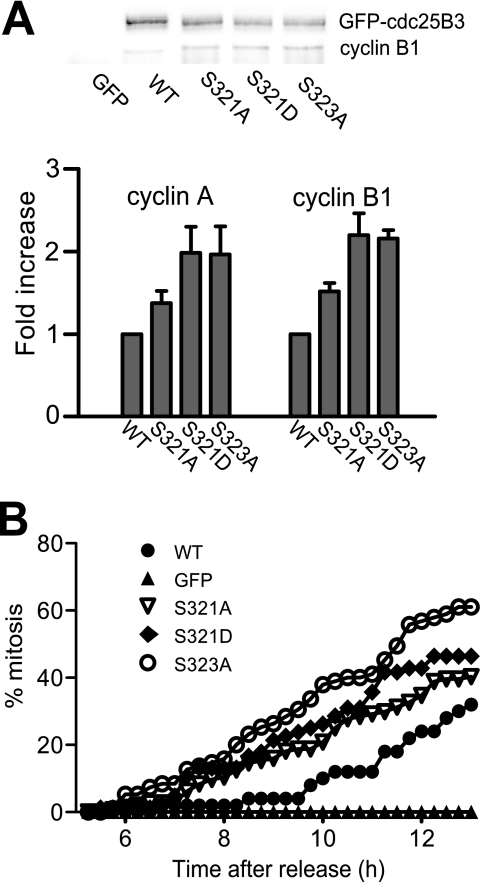

Mutation of Ser321 Increases Substrate Accessibility to the Catalytic Site and Activity of Cdc25B

We have shown previously that reduced 14-3-3 binding increased Cdc25B activity by increasing the access of the substrate cyclin/Cdks to the catalytic site of Cdc25B (12). To determine whether Ser321 mutation similarly affected Cdc25B substrate accessibility and thereby activity, HeLa cells were synchronized with thymidine block, and the G1/S-arrested population was transfected with the substrate trapping mutants of GFP-Cdc25B3 (C487S/R493K), which trap the substrates that access the catalytic residues (21), either wild type or mutant for Ser321 or carrying the S323A mutation or GFP. The levels of the cyclin subunits of the cyclin/Cdk substrates bound to the substrate trapping mutants were assessed as cells transited through G2/M phase. The S321D mutant demonstrated >2-fold increase in the associated cyclin A and cyclin B1 compared with the Ser321 wild type protein, which was essentially identical to the S323A 14-3-3 binding site mutant (Fig. 5A). The S321A mutant also showed increased cyclin binding, although to a lesser degree than the other mutants, but increased over the Ser321 wild type protein. This demonstrated that both Ser321 mutants increased substrate binding, although again, the S321A mutant was intermediate between the S321D and wild type, whereas S321D was essentially indistinguishable from the S323A mutant. The increased substrate accessibility to the catalytic site also suggested that both Ser321 mutants increased the activity of Cdc25B. To confirm this, GFP, catalytically active GFP-Cdc25B3 wild type, Ser321 or S323A mutants were transfected into G1/S-synchronized HeLa cells, which were then treated with etoposide (4 μm) to arrest the cells in G2 phase. The ability of the active GFP-Cdc25B3 mutants to abrogate the G2 phase arrest and drive cells into mitosis was monitored by time-lapse microscopy. HeLa cells stably overexpressing the antiapoptotic protein Bcl2 were used to minimize the apoptosis that could arise from combined synchrony, transfection, and etoposide treatments. The S321D mutant overcame the G2 arrest and drove cells into mitosis with similar kinetics to the S323A mutant, demonstrating that this mutation increased Cdc25 activity to a similar level as mutation of the high affinity 14-3-3 binding site (Fig. 5B). Again, the S321A mutant increased Cdc25B activity to a lesser extent that S321D mutant but was increased over the Ser321 wild type protein. This confirmed that Ser321 mutation increased Cdc25B activity; again, the S321D was essentially identical to the S323A mutant, whereas S321A was a weaker phenotype, intermediate between S321D and wild type Cdc25B.

FIGURE 5.

Ser321 mutation increases substrate binding and activity of Cdc25B. A, HeLa cells were synchronized at G1/S and transfected with substrate trapping mutants of GFP-Cdc25B3 and the indicated phosphorylation site mutants. 7 h post-transfection, the cells were harvested and immunoprecipitated to detect the interaction between GFP-Cdc25B3 and its substrate cyclin/Cdk, cyclin A, and cyclin B1. A representative set of immunoprecipitates of the indicated GFP-Cdc25B mutants immunoblotted for GFP-Cdc25B and cyclin B1 is shown. The fold increased binding of cyclin A and cyclin B1 over the Ser321 wild type protein, normalized for GFP-Cdc25B levels from three individual experiments is shown. B, HeLa cells were synchronized at G1/S and transfected with catalytically active GFP-Cdc25B3, either wild type (WT), the indicated phosphorylation site mutants, or GFP. Etoposide (4 μm) was added 5 h post-transfection to impose a G2 phase checkpoint arrest, and the timing of cells entering mitosis was monitored by time-lapse microscopy and scored as a percent of the total population. These data are representative of three individual experiments.

Ser323 Phosphorylation Is Reduced in Mitosis

The previous data demonstrated that the S321D mutant was essentially indistinguishable from the S323A mutant phosphorylation status could potentially regulate phosphorylation and 14-3-3 binding to Ser323; however, the timing of phosphorylation of Ser321 and Ser323 during the cell cycle was unknown. The phosphorylation state of Cdc25B on Ser323 through the cell cycle was examined using a phosphosite-specific antibody. U2OS cells expressing HA-Cdc25B3 under the control of a tetracycline-suppressible promoter were used to enhance the level of Cdc25B in the cells and detection of phosphorylated forms of the protein. U2OS cells were synchronized and induced to express HA-Cdc25B3 and followed through to mitosis. Phosphorylation of Ser323 was detected from S phase (4 h post-release) when the HA-Cdc25B was detected and maintained through to mitosis (peaked at 9 h post-release and marked by the highest level of cyclin B1 and Thr286-phosphorylated MEK1, a cyclin B/Cdk1 substrate and marker of mitosis (22, 23), then appeared to decrease (Fig. 6A)).

FIGURE 6.

Ser323 is phosphorylated during interphase and reduced in mitosis. A, U2OS cells expressing HA-Cdc25B were synchronized at G1/S by thymidine block and released in the absence of tetracycline to induce Cdc25B expression. The cells were harvested at indicated times and analyzed for Cdc25B Ser323 phosphorylation (pS323). The level of induced Cdc25B is shown (HA-Cdc25B), as are the levels of cyclin B1 Thr286 phosphorylated MEK1 as a marker of mitosis. PCNA was used as a loading control. The position of the 75-kDa marker is indicated by the bar on the left-hand side of the Cdc25B blots. B, the indicated substrate binding mutants of GFP-Cdc25B3and Myc-14-3-3β were transfected into HeLa cells, which were then synchronized by arrest in G2 phase with overnight of etoposide (G2), and mitotic sample produced by caffeine addition to the etoposide arrested cells for 5 h (M). Cells also were arrested in mitosis by overnight treatment with nocodazole (No). The mitotic cells from both the caffeine-promoted mitosis and nocodazole treatment were collected by mitotic shake-off. Lysates or immunoprecipitates of GFP-Cdc25B (GFP IP) were immunoblotted for the phosphorylation of Ser323 (pS323) of the overexpressed protein, the GFP-Cdc25B3, phosphorylated MEK1 Thr286 (pMEK T286) as a marker of cyclin B/Cdk1 activity and mitosis, and α-tubulin (α-tub) as a loading control. C, substrate binding site mutant of GFP-Cdc25B3 was transfected into HeLa cells that were then synchronized with thymidine. After release from the synchrony arrest, cells were treated without or with 250 nm okadaic acid (OA) 6 h after release and harvested 2 h later. Cells were immunoblotted for the indicated proteins. The position of the 100-kDa marker is indicated (bar). α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. D, substrate binding mutant of GFP-Cdc25B3 or GFP and Myc-14-3-3β were transfected in HeLa cells, synchronized, and then treated with or without okadaic acid as in C. GFP-Cdc25B was immunoprecipitated. Lysates were immunoblotted for the overexpressed protein (IB), and the immunoprecipitate for immunoblotted for the associated Myc-14-3-3β (IP) is indicated by the arrowhead. The faster migrating band was nonspecifically detected by the antibody in the immunoprecipitate.

To examine the phosphorylation of Ser323 phosphorylation in a highly synchronized population, overexpressed Cdc25B from G2 phase, normal mitotic, and nocodazole-treated HeLa cells also was analyzed for Ser323 phosphorylation. The normal mitotic and nocodazole-arrested mitotic cells were collected by mitotic shake-off to enhance the mitotic population in each sample. Ser323 was phosphorylated in G2 phase cells and persisted on Cdc25B from mitotic cells, although Ser323 phosphorylation was reduced in nocodazole-arrested cells (Fig. 6B). The Ser323 phosphorylation was associated with 14-3-3 binding, with the level of 14-3-3β binding reflecting the level of Ser323 phosphorylation. There is dynamic phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of Ser323 in mitotic cells. Addition of the phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid increased Ser323 phosphorylation on the wild type protein and the S321A mutant, although not to the extent of the wild type protein, whereas no Ser323 phosphorylation was detected with the S321D mutant under any conditions (Fig. 6C). This suggests that the introduction of the acidic Asp blocked phosphorylation of Ser323, whereas the S321A mutation could support the phosphorylation of Ser323, but this phosphorylation was highly susceptible to dephosphorylation. This may explain the variability of 14-3-3β and -ϵ binding to the S321A mutant we have observed (Fig. 2C). The okadaic acid induced increased Ser323 phosphorylation supported increased 14-3-3β binding (Fig. 6D).

Multiple Cdk1-dependent phosphorylation sites have been identified on Cdc25B (24). These were responsible for the electrophoretically retarded forms of Cdc25B seen in mitotic cells, as they were rapidly reduced to the higher mobility interphase forms by a 30-min treatment with the Cdk1-selective inhibitor RO-3306 (Fig. 7A) (25). One of the sites phosphorylated by Cdk1 in mitotic cells was Ser321, which was detected in mitotic cells with a phospho-Ser321-specific antibody and effectively reduced with prior treatment with the Cdk1 inhibitor (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

Cdc25B is phosphorylated at multiple sites including Ser321 in mitosis by Cdk1. A, HeLa cells were synchronized at G1/S by thymidine block, and cells were harvested at 7 (G2) and 9.5 h post-release mitotic (M), or arrested overnight with nocodazole (No), either without or with addition of RO-3306 (Cdk1i) 30 min prior to harvesting. The mitotic cells from both the thymidine synchrony and nocodazole treatment were collected by mitotic shake-off. Lysates were immunoblotted for Cdc25B. The position of the 75-kDa marker is indicated (bar). B, HeLa cells were transfected with the substrate binding site mutant of GFP-Cdc25B3 or empty vector (Vec), synchronized with thymidine, and harvested in G2 or mitosis, or at the same time as the mitotic sample but in the presence of 9 μm Cdk1 inhibitor RO-3306 added 2 h prior to harvesting (+Cdk1i). Lysates were immunoblotted for pSer321, GFP-Cdc25B3, and pMEK Thr286 as a marker of mitosis, and MEK1 as a loading control. The position of the 100-kDa marker is indicated (bar).

DISCUSSION

Tight control of Cdc25B is important for regulating progression through G2 phase into mitosis and for exit from a G2 phase checkpoint arrest where there is a specific requirement for Cdc25B (4, 26). In this study, we have demonstrated that the Ser at position −2 amino acids to the high affinity 14-3-3 binding site, Ser323 of Cdc25B3, disrupts 14-3-3 binding to this site. The consequences of disrupted 14-3-3 binding were increased activity through increased access of the substrate cyclin/Cdks to the catalytic site on Cdc25B and increased nuclear localization. The effects of mutation of Ser321 to either Ala to block phosphorylation or the phosphomimetic Asp revealed much about how the phosphorylation of this site by Cdk1 in mitosis may influence 14-3-3 binding to the Ser323 site and thereby Cdc25B function. The S321D mutant behaved identically to the S323A mutant in all the functional assays performed here. This is unsurprising, as this mutation ablated Ser323 phosphorylation, effectively behaving as a S323A mutant. It is likely that substitution of Ser321 with Asp is inhibiting phosphorylation of Ser323 due to the introduction of an acid residue at position −2 from the phosphorylated residue, even though the primary phosphorylation site preferences of MAPKAPK2 and Chk1, the two major Ser323 kinases (27), show that both can tolerate any amino acid at position −22 (28, 29). This is evident from that lack of effect of okadaic acid treatment on the S321D mutant, which increased Ser323 phosphorylation on both the Ser321 wild type and Ala mutant. The increased Ser323 phosphorylation in the S321A mutant indicates that one of the consequences of reduced 14-3-3 binding is the increased dephosphorylation of Ser323 due to increased phosphatase access.

The S321A mutant was not equivalent to the wild type protein, but the effect of this mutation was variably less severe than the S321D and S323A mutants in all assays reported here. This variability is likely to be a consequence of the readily reversible loss of phosphorylation on Ser323 with this mutant. Whereas the S321D mutation appears to completely block phosphorylation of Ser323, the S321A mutation is permissive for Ser323 phosphorylation but allows more ready access of phosphatases to dephosphorylate Ser323. We propose that this is a consequence of reduced 14-3-3 binding to the S321A mutant. Ser323 lies in the mode 1 14-3-3 binding motif RSXpSXP, RSPpS323MP. Ser at at position −2 residues has been reported to confer high affinity binding by making a hydrogen bond between the hydroxyl of the Ser with the Glu180 and Trp228 of 14-3-3 (30). The substitution of Ser with Ala at this site would reduce the binding affinity of 14-3-3 by loss of the hydrogen bond. The added charge of the Asp mutation would have a more dramatic effect than the loss of hydroxyl with the Ala mutation, and possibly also disrupt the ability of the Ser323 kinase to phosphorylate Ser323.

The mutation analysis of Ser321 indicates that introducing a strong acidic group into the Ser321 site severely disrupts normal 14-3-3 binding to the high affinity Ser323 site. This is likely to be a direct consequence of disrupting 14-3-3 binding to the phosphorylated Ser323 site, which appears to be phosphorylated at least from S phase. The phosphorylation of Ser321 has been shown to be regulated by Cdk1 in vitro, and it also is phosphorylated in vivo (24). We have shown that this site also is phosphorylated in mitosis, similarly to the equivalent site in Cdc25C, Ser214 (17). Mass spectroscopy sequencing of the in vivo-phosphorylated Cdc25B failed to detect a peptide containing both Ser323 and Ser321 phosphorylations (24), and the loss of Ser323 phosphorylation on the S321D mutant is further evidence that the two phosphorylations do not co-exist on Cdc25B in mitosis. We propose a model whereby increased Ser321 phosphorylation by Cdk1 promotes the rapid dephosphorylation of Ser323, similar to that proposed for Xenopus Cdc25C. The hydroxyl group on Ser321 is likely to contribute to 14-3-3 binding to Ser323, and its phosphorylation is sufficient to destabilize the binding of 14-3-3 to Ser323 and enhance Ser323 dephosphorylation, to ensure 14-3-3 does not rebind this site, as shown with Xenopus Cdc25C (31). This can occur only after removal of 14-3-3 from the phosphorylated residue as 14-3-3 binding fully encompasses the phosphate, which would protect it from access by the phosphatase (30).

Although Cdk1-dependent Ser321 phosphorylation can regulate Ser323 phosphorylation and 14-3-3 binding to this site, the persistence of Ser323 phosphorylation and 14-3-3 binding to Cdc25B in normal mitosis, and even in the extended mitotic arrest induced by nocodazole treatment, suggests that it is not critical for Cdc25B activation in G2/M phase. Cdc25B is active from early G2 phase (32) when Ser323 phosphorylation is maximal, Cdk1 activity is low, and Ser321 phosphorylation is not detectible, pointing to other mechanisms activating Cdc25B in G2 phase. This is likely to be through loss of binding to the N-terminal 14-3-3 binding sites, Ser151 and Ser230, which also results in activation of Cdc25B and its relocation to the cytoplasm (12), as has been observed for Cdc25B in G2 phase (1, 4, 33). In the case of Cdc25C, the hyperphosphorylated, activated form, which has gained Ser214 phosphorylation and lost Ser216 phosphorylation, is only detected in mitotic cells and is the predominant form of Cdc25C in mitotic arrested cells (17, 32). Thus, whereas Ser214 phosphorylation is likely to be a critical contributor to the mitotic activation of Cdc25C, the phosphorylation of Ser321 does not appear to be a major contributor to Cdc25B activation but contributes to the maintenance of its activity in mitosis. The loss of Cdc25B in an extended mitotic arrest suggests that the major role of Cdc25B being to drive entry into mitosis as suggested previously (1, 4), rather than maintenance of cyclin B/Cdk1 activation in mitosis. The necessity to maintain cyclin B/Cdk1 activation is readily demonstrated by the rapidity with which mitotic exit can be induced with addition of a Cdk1 inhibitor. Thus, whereas Cdc25B drives mitotic entry, Cdc25C is activated through Cdk1-dependent Ser214 phosphorylation to maintain cyclin B/Cdk1, especially under conditions of mitotic arrest.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) and the Australian Research Council.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gabrielli B. G., De Souza C. P., Tonks I. D., Clark J. M., Hayward N. K., Ellem K. A. (1996) J. Cell Sci. 109, 1081–1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karlsson C., Katich S., Hagting A., Hoffmann I., Pines J. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 146, 573–584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lammer C., Wagerer S., Saffrich R., Mertens D., Ansorge W., Hoffmann I. (1998) J. Cell Sci. 111, 2445–2453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindqvist A., Källström H., Lundgren A., Barsoum E., Rosenthal C. K. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 171, 35–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstone S., Pavey S., Forrest A., Sinnamon J., Gabrielli B. (2001) Oncogene 20, 921–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldin V., Cans C., Superti-Furga G., Ducommun B. (1997) Oncogene 14, 2485–2495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forrest A. R., McCormack A. K., DeSouza C. P., Sinnamon J. M., Tonks I. D., Hayward N. K., Ellem K. A., Gabrielli B. G. (1999) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 260, 510–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldin V., Cans C., Knibiehler M., Ducommun B. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 32731–32734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Astuti P., Pike T., Widberg C., Payne E., Harding A., Hancock J., Gabrielli B. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 33781–33788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isoda M., Kanemori Y., Nakajo N., Uchida S., Yamashita K., Ueno H., Sagata N. (2009) Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 2186–2195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forrest A., Gabrielli B. (2001) Oncogene 20, 4393–4401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giles N., Forrest A., Gabrielli B. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 28580–28587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uchida S., Kuma A., Ohtsubo M., Shimura M., Hirata M., Nakagama H., Matsunaga T., Ishizaka Y., Yamashita K. (2004) J. Cell Sci. 117, 3011–3020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bugler B., Quaranta M., Aressy B., Brezak M. C., Prevost G., Ducommun B. (2006) Mol. Cancer Ther. 5, 1446–1451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sohn J., Kristjánsdóttir K., Safi A., Parker B., Kiburz B., Rudolph J. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 16437–16441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sohn J., Parks J. M., Buhrman G., Brown P., Kristjánsdóttir K., Safi A., Edelsbrunner H., Yang W., Rudolph J. (2005) Biochemistry. 44, 16563–16573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bulavin D. V., Higashimoto Y., Demidenko Z. N., Meek S., Graves P., Phillips C., Zhao H., Moody S. A., Appella E., Piwnica-Worms H., Fornace A. J., Jr. (2003) Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 545–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Theis-Febvre N., Filhol O., Froment C., Cazales M., Cochet C., Monsarrat B., Ducommun B., Baldin V. (2003) Oncogene. 22, 220–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atherton-Fessler S., Liu F., Gabrielli B., Lee M. S., Peng C. Y., Piwnica-Worms H. (1994) Mol. Biol. Cell 5, 989–1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmitt E., Boutros R., Froment C., Monsarrat B., Ducommun B., Dozier C. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119, 4269–4275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu X., Burke S. P. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 5118–5124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Boer L., Oakes V., Beamish H., Giles N., Stevens F., Somodevilla-Torres M., Desouza C., Gabrielli B. (2008) Oncogene 27, 4261–4268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossomando A. J., Dent P., Sturgill T. W., Marshak D. R. (1994) Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 1594–1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bouché J. P., Froment C., Dozier C., Esmenjaud-Mailhat C., Lemaire M., Monsarrat B., Burlet-Schiltz O., Ducommun B. (2008) J. Proteome Res. 7, 1264–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vassilev L. T., Tovar C., Chen S., Knezevic D., Zhao X., Sun H., Heimbrook D. C., Chen L. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 10660–10665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Vugt M. A., Brás A., Medema R. H. (2004) Mol. Cell 15, 799–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boutros R., Lobjois V., Ducommun B. (2007) Nat. Rev. Cancer. 7, 495–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stokoe D., Caudwell B., Cohen P. T., Cohen P. (1993) Biochem. J. 296, 843–849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Neill T., Giarratani L., Chen P., Iyer L., Lee C. H., Bobiak M., Kanai F., Zhou B. B., Chung J. H., Rathbun G. A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 16102–16115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gardino A. K., Smerdon S. J., Yaffe M. B. (2006) Semin. Cancer. Biol. 16, 173–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Margolis S. S., Perry J. A., Weitzel D. H., Freel C. D., Yoshida M., Haystead T. A., Kornbluth S. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 1779–1789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gabrielli B. G., Clark J. M., McCormack A. K., Ellem K. A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 28607–28614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindqvist A., Källström H., Karlsson Rosenthal C. (2004) J. Cell Sci. 117, 4979–4990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]