Abstract

Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) is a molecule capable of initiating the release of intracellular Ca2+ required for many essential cellular processes. Recent evidence links two-pore channels (TPCs) with NAADP-induced release of Ca2+ from lysosome-like acidic organelles; however, there has been no direct demonstration that TPCs can act as NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ release channels. Controversial evidence also proposes ryanodine receptors as the primary target of NAADP. We show that TPC2, the major lysosomal targeted isoform, is a cation channel with selectivity for Ca2+ that will enable it to act as a Ca2+ release channel in the cellular environment. NAADP opens TPC2 channels in a concentration-dependent manner, binding to high affinity activation and low affinity inhibition sites. At the core of this process is the luminal environment of the channel. The sensitivity of TPC2 to NAADP is steeply dependent on the luminal [Ca2+] allowing extremely low levels of NAADP to open the channel. In parallel, luminal pH controls NAADP affinity for TPC2 by switching from reversible activation of TPC2 at low pH to irreversible activation at neutral pH. Further evidence earmarking TPCs as the likely pathway for NAADP-induced intracellular Ca2+ release is obtained from the use of Ned-19, the selective blocker of cellular NAADP-induced Ca2+ release. Ned-19 antagonizes NAADP-activation of TPC2 in a non-competitive manner at 1 μm but potentiates NAADP activation at nanomolar concentrations. This single-channel study provides a long awaited molecular basis for the peculiar mechanistic features of NAADP signaling and a framework for understanding how NAADP can mediate key physiological events.

Keywords: Calcium Intracellular Release, Calcium Transport, Ion Channels, Lysosomes, Membrane Biophysics, Calcium Signaling, Intracellular Calcium Release Channel, NAADP

Introduction

Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP)4 is the most potent Ca2+-releasing second messenger yet identified (1–4). Although originally discovered in sea urchin eggs, it is becoming increasing clear that NAADP-induced Ca2+ release is crucial to many physiological processes in a diverse range of mammalian cell types (5, 6). Many distinctive features of NAADP-induced Ca2+ release indicate that the Ca2+ release channels involved are functionally and structurally different from the well characterized Ca2+ release channels found on sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum stores (ryanodine receptors (RyRs) and inositol trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs) (7, 8)). NAADP triggers Ca2+ release from acidic stores, but the identity of the Ca2+ release channel involved has remained a mystery (7). New evidence has shown that NAADP binds with high affinity to TPC protein complex (9), which is located on acidic, lysosome-like Ca2+ stores (10, 11). A recent report also demonstrates that activation of cell surface muscarinic receptors requires TPC2 expression to couple Ca2+ release from acidic stores in mouse bladder smooth muscle (12). The importance of TPC2 to Ca2+ movements across lysosomal membranes was recently shown in whole lysosome recordings. Mutation of TPC2 affected the magnitude of whole lysosomal Ca2+ currents, highlighting the need to investigate the conductance and gating properties of TPC2 at the single-channel level (13).

TPCs are thus named because their close sequence homology with voltage-gated cation channels predicts a monomeric structure containing two pore loops (7, 14). It is proposed that two homodimers form the pore (10, 15, 16); however, it is not known whether TPC2 can actually function as an ion channel with all the properties necessary to fulfill the role of a Ca2+ release channel activated by NAADP. Many characteristics of NAADP-induced Ca2+ release distinguish it from Ca2+ release triggered by other signaling molecules, and these indicate unusual underlying mechanisms of ion channel function.

For the first time, we describe here the fundamental single-channel gating and conductance properties of purified human TPC2 and demonstrate that TPC2 exhibits many unique functional characteristics that can explain the idiosyncrasies of cellular NAADP signaling characteristics, whereas cardiac (RyR2) and skeletal (RyR1) RyRs do not. A preliminary report of these data has been presented in abstract form (17).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Purification of Human, Recombinant TPC2

cDNA for hTPC2 (GenBankTM accession number AY029200) was cloned from HEK293 cells by rapid amplification of cDNA ends-PCR using primers designed against the expressed sequence tag AA309878 (10). Overexpressing HA-HsTPC2 HEK293 cells were harvested and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C. The cell pellet was resuspended in hypotonic buffer (20 mm HEPES, 1 mm EGTA, pH 7.2) and kept for 60 min on ice before homogenization. The lysate was centrifuged for 5 min at 2000 × g at 4 °C, and the supernatant was centrifuged for 1 h at 100,000 × g at 4 °C. The membrane pellet was resuspended in IP buffer (150 mm NaCl, 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.4) and kept on ice for 1 h, after which insoluble material was pelleted by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was precleared by adding non-immune rabbit serum coupled covalently to protein-A-Sepharose for 1 h at 4 °C. The precleared supernatant was incubated overnight at 4 °C with either non-immune rabbit serum (control) or polyclonal anti-TPC2 antibody (10), both covalently coupled to protein-A-Sepharose beads. The beads were pelleted by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 2 min. Following removal of the supernatant, the beads were washed with IP buffer containing 1% CHAPS followed by two washes containing 0.1% CHAPS. Immunoprecipitated protein complexes were eluted by incubation with the peptides used to raise the antibody, at 50 μg/ml in 0.1% CHAPS and 0.05% phosphatidylcholine for 4 h at 4 °C. The eluted protein complexes were dialyzed for 36 h at 4 °C in buffer containing 100 mm NaCl, 25 mm PIPES, 0.15 mm CaCl2, and 0.1 mm EGTA, pH 7.4, using a 20,000 molecular weight cut-off filter. After dialysis, an equal volume of 0.5 m sucrose solution was added and incubated for 30 min at 4 °C before aliquoting and snap freezing in liquid nitrogen. Further information is provided in supplemental Methods.

Single Channel Recording and Analysis

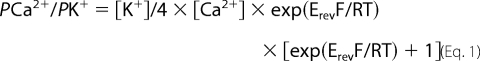

Purified TPC2, rabbit skeletal RyR1, or sheep cardiac RyR2 was incorporated into planar phosphatidylethanolamine lipid bilayers under voltage clamp conditions using previously described techniques (18). Current fluctuations were recorded at 22 ± 2 °C with either Ca2+ (cis, 250 mm HEPES, 80 mm Tris, 15 μm free Ca2+, pH 7.2/trans, 250 mm glutamic acid, 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.2 with Ca(OH)2 giving a free [Ca2+] of 50 mm) or K+ (symmetrical 210 mm KCl, 10 mm HEPES, 15 μm free Ca2+, pH 7.2) as the permeant ion. Luminal pH was lowered to 4.8 by perfusing the trans chamber with a solution of 210 mm potassium acetate, 10 mm HEPES, 15 μm free [Ca2+]. Replacement of Cl− by acetate did not alter TPC2 conductance or gating (data not shown). Washout of the cis (cytosolic) chamber to exchange solutions took 2 min. The free [Ca2+] of all solutions was determined using a Ca2+ electrode (Orion 93-20; Thermo Orion, Boston, MA) as described previously (18). Current recordings were filtered at 800 Hz (−3 db) and digitized at 20 kHz (ITC-18, Instrutech Corporation) with WinEDR version 2.5.9 (Strathclyde University, UK) or Pulse (HEKA Elektronik, Lambrecht/Pfalz Germany). Measurements of single-channel current amplitudes were made using the single-channel analysis software WinEDR version 2.5.9 (University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK). The closed and open current levels were assessed manually using cursors. Amplitude histograms were obtained from single-channel data using Clampfit version 10.2 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and fitted with Gaussian curves. In all records, amplitude histograms were best fit with a single Gaussian function representing the main conductance level (300 pS; see Fig. 2b). Subconductance state gating was too brief to be detected by this method of analysis. The channel open probability (Po) was determined over 3 min of continuous recording, using the method of 50% threshold analysis (19). Concentration-response curves were fit using a four-parameter logistical equation in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc). The Ca2+/K+ permeability ratio (PCa2+/PK+) was calculated using the equation given by Fatt and Ginsborg (1958) (20).

|

The value of RT/F used in our calculations was 25.4 mV based on the recording temperature of 22 °C. The zero current reversal potential (Erev) was obtained under bi-ionic conditions (cis, 210 mm KCl, 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.2; trans, 210 mm CaCl2, 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.2) and represented the point where no current could be detected. Ned-19 was synthesized as described previously (21), and the l-trans-Ned-19 analog was used throughout.

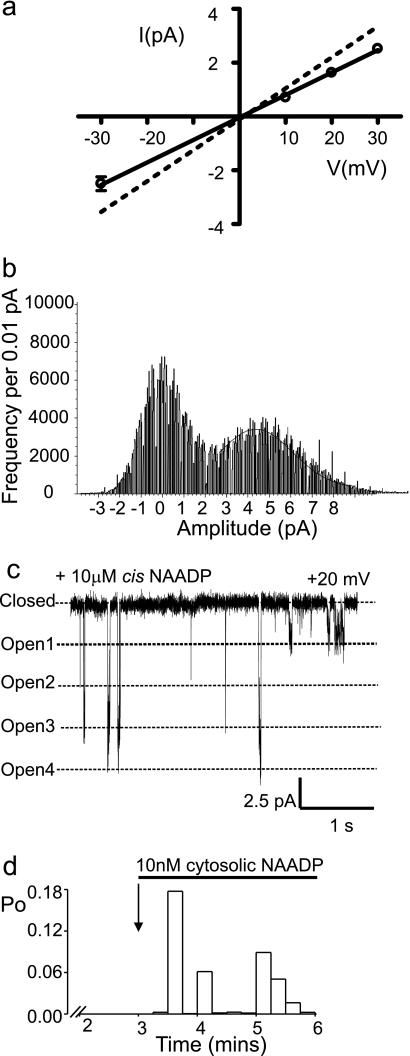

FIGURE 2.

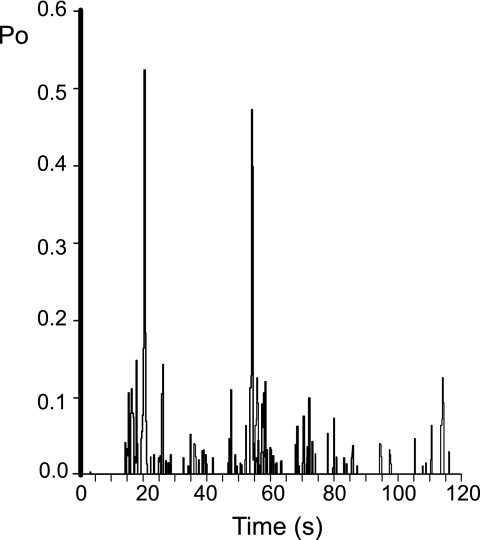

Distinct gating characteristics of TPC2. a, the current-voltage relationship reveals a subconductance state that is 212 ± 12 pS (n = 5), ∼70% of the fully open channel level. As a direct comparison, the dotted line shows the current-voltage relationship of the fully open state (Fig. 1c). b, all-points amplitude histogram obtained from TPC2 single-channel current fluctuations obtained at +20 mV in symmetrical 210 mm KCl, pH 7.2. The histogram was best fit with a single Gaussian function and gave a mean single-channel current amplitude value of 4.3 ± 0.13 pA corresponding to the fully open channel level. We observed the subconductance gating state in all our recordings, yet because of the low incidence of occurrence, the subconductance state of TPC2 cannot be accurately detected with an amplitude histogram. c, a typical example of episodic coupled gating of multiple TPC2 channels. d, histogram showing the time dependence of NAADP activation. For this analysis, we used a very low [NAADP], essentially a threshold concentration at the foot of the concentration-response relationship (and therefore a concentration that does not activate all channels). This was to investigate whether, because of the irreversible effect of NAADP, Po might gradually increase over time following initial activation. The figure indicates that it does not gradually increase over time, although non-stationary gating behavior was very obvious (as reported for many other ion channels, for example, RyR2 (47)). The average time to onset under these conditions (10 nm NAADP, 10 μm luminal [Ca2+], pH 7.2) was 44 ± 10 s (n = 5).

Statistics

Mean ± S.D. (≥3) is shown unless otherwise stated. Student's t test was used to assess the difference between mean values. A p value of <0.05 was taken as significant.

RESULTS

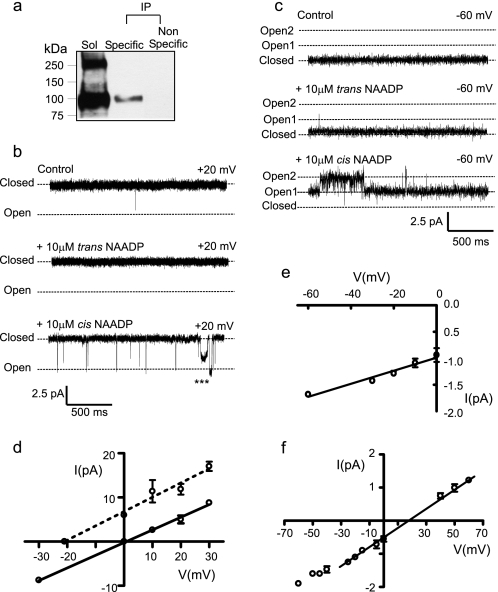

We purified the human recombinant TPC2 complex (Fig. 1a) for subsequent reconstitution into artificial membranes under voltage clamp conditions (18). Representative examples of the resulting single-channel currents in symmetrical solutions of 210 mm KCl, pH 7.2, are shown in Fig. 1b. In the absence of NAADP, occasional channel openings, usually too brief to fully resolve, were observed. NAADP addition to the cis chamber always increased Po (n = 101), whereas trans addition of NAADP had no effect (n = 5). In conditions where luminal Ca2+ was the permeant ion (Fig. 1c), NAADP still activated TPC2 from the cytosolic side only (n = 15). TPC2, therefore, incorporates into bilayers in a fixed orientation as described in the supplementary text, with the cis and trans chambers, most likely corresponding to the cytosolic and luminal sides of the acidic Ca2+ stores, respectively. These single-channel currents were not observed in control experiments (supplemental Fig. S1).

FIGURE 1.

TPC2 is a functional ion channel activated by NAADP. a, anti-HA immunoblot of protein incorporated into bilayers. Sol corresponds to solubilized sample before IP, Specific corresponds to IP with anti-HsTPC2 serum, and Nonspecific corresponds to a control IP with non-immune rabbit serum. b and c, a typical single-channel experiment showing sequential additions of NAADP to the trans and cis chambers with K+ (b) or Ca2+ (c) as permeant ion. d and e, current-voltage relationships with K+ or Ca2+, respectively, as permeant ion. The dotted line in d illustrates the KCl gradient (trans, 210 mm; cis, 510 mm) data. f, the relative permeability of TPC2 to K+ and Ca2+. The single-channel current-voltage relationship with 210 mm KCl in the cis chamber and 210 mm CaCl2 in the trans chamber yields a reversal potential of 26 ± 1 mV (n = 3). The PCa2+/PK+ was calculated to be 2.6 ± 0.17. The bi-ionic conductance over the range −30 to +60 mV (22 ± 3 pS (n = 3)) is similar to that obtained using only Ca2+ as the permeant ion (15 ± 1.5 pS) as expected if Ca2+ is the ion predominantly flowing through the channel at potentials close to 0 mV.

In symmetrical 210 mm KCl, the single-channel conductance (Fig. 1d) was 300 ± 6 pS (S.E.; n = 5). Applying a KCl gradient (trans, 210 mm; cis, 510 mm), shifted the current-voltage relationship to the left with a reversal potential of −20.5 mV, indicating that, as for other Ca2+ release channels (22, 23), TPC2 is ideally selective for cations. The current-voltage relationship shown in Fig. 1e revealed a Ca2+ conductance of 15 ± 1.5 pS (S.E.; n = 5), which is very small when compared with that for RyR2 (120 pS (24)) and IP3R (53 pS (23, 25)), using identical recording solutions. The relative permeability of TPC2 to monovalent and divalent cations was assessed by monitoring conductance with 210 mm K+ cis and 210 mm Ca2+ trans. As shown in Fig. 1f, under these conditions a Ca2+/K+ permeability ratio (PCa2+/PK+) of 2.6 was obtained. Thus, like RyR and IP3R, TPC2 is selective for cations but lacks strong discrimination between monovalent and divalent cations (22–24). These ion conduction properties of TPC2 predict a small unitary Ca2+ current through a single TPC2 channel under physiological conditions. This may explain some of the cellular characteristics of NAADP-activated Ca2+ release where small, localized rises in cytosolic Ca2+ either do not propagate throughout the cell (26) or require close proximity to the sarcoplasmic reticulum to trigger greater release of Ca2+ via RyR (27, 28) or IP3R (10). The small Ca2+ current expected through individual TPC2 channels provides an adaptable system; small Ca2+ release events are possible, but large Ca2+ fluxes could also be generated with high Ca2+ loading of stores if many TPC2 channels were closely arranged, especially if the gating of clusters of channels was coordinated (as appears to be a characteristic of TPC2; see point 3 below). TPC2 channel gating was characterized by four distinguishing features. 1) constitutive, infrequent brief openings in the absence of NAADP, which were not abolished by reducing cytosolic or luminal Ca2+ to 1 nm (data not shown); 2) transitions to a subconductance state (Fig. 1b, asterisks) ∼70% of the fully open channel level as detailed in Fig. 2, a and b; 3) episodic gating where multiple channels appear to open (and close) simultaneously in a synchronized or coupled fashion as shown in Fig. 2c; 4) slow onset in NAADP-induced activation as illustrated in Fig. 2d where Po was measured in 5-s segments.

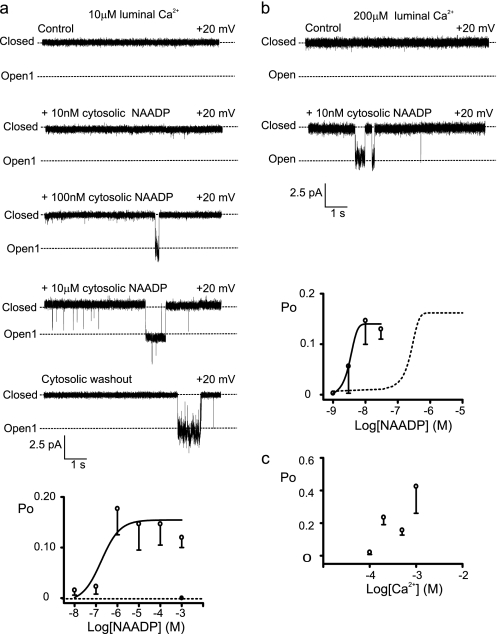

Fig. 3a shows TPC2 activation by NAADP. If [NAADP] was incremented in a cumulative fashion, channel activation plateaued at ∼1 μm (Fig. 3a), and higher [NAADP] had no further effect. However, if 1 mm NAADP was applied without first pretreating with activating concentrations, then the channels shut (supplemental Fig. S2), indicating that high affinity activation and lower affinity inactivation sites are likely (29, 30). Washout of NAADP did not reverse TPC2 activation (Fig. 3a, bottom trace), demonstrating that the activating action of NAADP was irreversible on the timescale of a single-channel experiment.

FIGURE 3.

Effects of NAADP and luminal Ca2+ on TPC2 gating. a, the upper panel shows a representative experiment showing sequential increases in [NAADP] using K+ as permeant ion followed by washout of NAADP from the cis chamber (bottom trace). The lower panel shows an NAADP concentration-response relationship. The addition of 1 mm NAADP without first pretreating with activating concentrations is shown by the filled circle (n = 4). Error bars represent mean ± S.D. (n ≥ 3). b, a typical experiment, using K+ as permeant ion, showing that in the presence of 200 μm luminal Ca2+, very low [NAADP] (10 nm) can activate TPC2. The lower panel shows an NAADP concentration-response relationship in the presence of 200 μm luminal Ca2+. The dashed curve shows the data from a as a comparison. c, the relationship between TPC2 Po and luminal [Ca2+] in the presence of 10 nm NAADP. Data are mean ± S.D. (n ≥ 3).

Unexpectedly, the EC50 value (500 nm) was much higher than the Kd values reported for NAADP binding to membranes isolated from cells overexpressing TPC2 (5 nm) or membranes isolated from mouse liver (6.6 nm) (10), and we therefore investigated the possibility that physiological environmental factors could modulate TPC2 sensitivity to NAADP. The known Ca2+ release channels of the sarcoplasmic reticulum/endoplasmic reticulum are very sensitive to luminal Ca2+ (23, 31, 32). We therefore investigated whether TPC2 could also be regulated by luminal Ca2+. Fig. 3a shows that at 10 μm luminal [Ca2+], 10 nm NAADP has little effect on TPC2. If, however, luminal Ca2+ is raised to 200 μm (Fig. 3b), then 10 nm NAADP becomes an optimally effective concentration, and the NAADP concentration-response relationship is shifted to the left with a dramatic 100-fold reduction in the EC50 value to 5 nm. Luminal Ca2+ therefore enables extremely low levels of NAADP to open TPC2. Fig. 3c shows that in the presence of 10 nm NAADP, which alone is ineffective, luminal Ca2+ increases Po in a concentration-dependent manner. It is significant that the range of luminal [Ca2+] that affects TPC2 Po (10 μm–1 mm) falls within the expected range of luminal [Ca2+] within lysosomal stores (33). These results suggest that NAADP-induced Ca2+ release in situ would be steeply dependent on lysosomal Ca2+ load. Depletion of Ca2+ stores below a threshold level could terminate TPC2 Ca2+ flux even in the maintained presence of NAADP, allowing for refilling of the stores until the threshold was again reached. This mechanism of luminal Ca2+ control could lead to the Ca2+ oscillations that are characteristic of NAADP signaling in physiological systems (10, 29, 34).

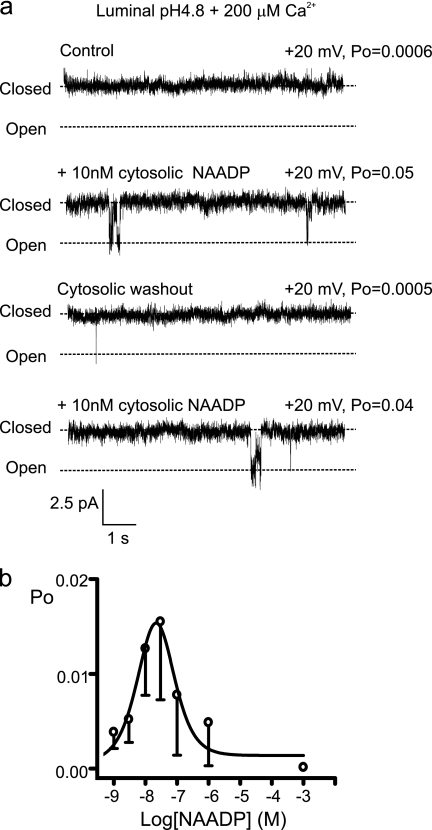

Because TPCs are present on acidic stores and because NAADP induces alkalinization of acidic stores in sea urchin eggs (35), it is therefore important to ask whether pH affects TPC2 function. Fig. 4, a and b, demonstrate that when luminal pH is reduced from 7.2 to 4.8, TPC2 remains sensitive to low concentrations of NAADP (EC50 = 5.5 nm), although Po levels are decreased. Importantly, activation by NAADP becomes reversible at luminal pH 4.8 (Fig. 4a, third trace), and the concentration-response relationship becomes bell-shaped (Fig. 4b), as is widely observed for NAADP-induced Ca2+ fluxes in mammalian cells (29). In this way, luminal pH behaves as a molecular switch, modifying the conformation of the NAADP binding site so that NAADP can dissociate from TPC2. The final Po achieved by a rise in NAADP levels is therefore a function of both the luminal pH and the luminal-free [Ca2+]. In a cellular situation, such control would be expected to amplify the diversity of the NAADP signal as luminal pH could toggle between long lasting and transient Ca2+ release events.

FIGURE 4.

Luminal pH regulates TPC2. a, a representative experiment with K+ as the permeant ion in the presence of 200 μm luminal [Ca2+] at low luminal pH (4.8). 10 nm NAADP activates the channel (second trace). Washout of NAADP shows that NAADP binding is reversible, and subsequent addition of NAADP (10 nm) reopens the channel. b, Relationship between TPC2 Po and [NAADP] with K+ as the permeant ion, 200 μm luminal [Ca2+], luminal pH (4.8). Data are mean ± S.D. (n ≥ 3).

Because NAADP regulation of TPC2 is so heavily dependent on the luminal pH and [Ca2+], can these factors affect the latency of the NAADP response? Our experiments do not provide any evidence that the luminal environment plays a significant role in determining the rate of onset of channel activation, but the concentration of NAADP appears to be very important. Fig. 5 demonstrates that high concentrations of NAADP activate the channel with a significantly shorter delay than very low concentrations of NAADP. This is not unexpected for a ligand-gated ion channel.

FIGURE 5.

The slow onset of NAADP-induced TPC2 channel activation is concentration-dependent. The histogram monitors Po over time by breaking up the data into 200-ms segments. We used a high concentration of NAADP (10 μm) in the presence of 10 μm luminal [Ca2+], pH 7.2. The average time to onset was 14 ± 1 s (n = 3). This compares with 44 ± 10 s (n = 5; p < 0.05) under identical conditions when a very low, threshold concentration of NAADP was used (10 nm), as described in the legend for Fig. 2. The non-stationary or modal gating behavior is still operating at high [NAADP]. To investigate whether luminal factors affect the rate of onset of NAADP activation of TPC2, we again chose a very low, threshold level of NAADP. 10 nm NAADP is an optimally effective concentration in the presence of 200 μm luminal [Ca2+], so we used the threshold concentration of 1 nm NAADP. Average time to onset of activation was: (i) 50 ± 5 s (n = 3) for 1 nm NAADP with 200 μm luminal [Ca2+], pH 7.2; (ii) 41 ± 16 s (n = 3) for 1 nm NAADP with 200 μm luminal [Ca2+], pH 4.8. These results suggest that the luminal environment does not affect the rate of onset of NAADP-induced activation of TPC2, but a more detailed kinetic analysis will be needed for a better understanding of this phenomenon.

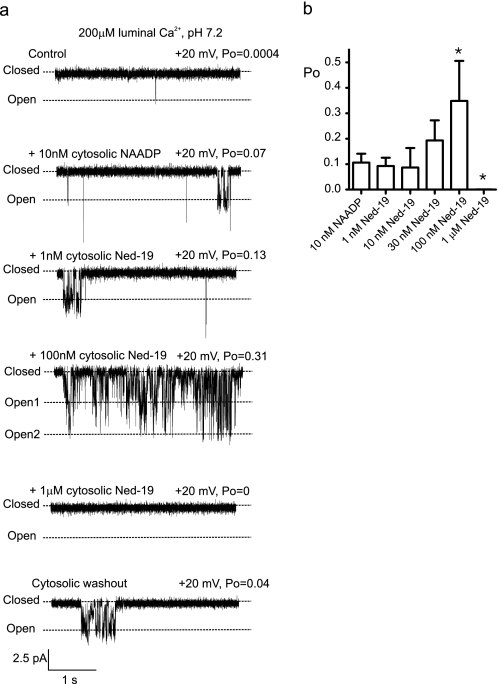

A key feature of NAADP-induced Ca2+ release is selective inhibition by the NAADP antagonist, Ned-19 (21, 36). We therefore investigated whether Ned-19 could antagonize NAADP activation of TPC2. Fig. 6a shows a typical experiment where TPC2 is activated by 10 nm NAADP. In the continued presence of NAADP, Ned-19 dose-dependently increased Po at low nanomolar levels but completely shut the channel at 1 μm (mean data shown in Fig. 6b). Washout of both NAADP and Ned-19 (Fig. 6a, bottom trace) reversed the inhibitory effects of Ned-19 but not the activation by NAADP, thereby demonstrating that Ned-19 does not close TPC2 by binding to NAADP activation sites.

FIGURE 6.

Effects of Ned-19 on TPC2. a, a typical experiment illustrating TPC2 channels gating in the bilayer in the presence of 200 μm luminal Ca2+ (K+ is the permeant ion), pH 7.2. Cytosolic NAADP (10 nm) followed by sequential increments in cytosolic Ned-19 levels was applied as indicated. Po values are shown above the relevant trace. The bottom trace shows the effect of washing out both compounds from the cis chamber; only the effects of Ned-19 are reversible. b, concentration dependence of Ned-19 effects in the presence of NAADP (*, p < 0.05).

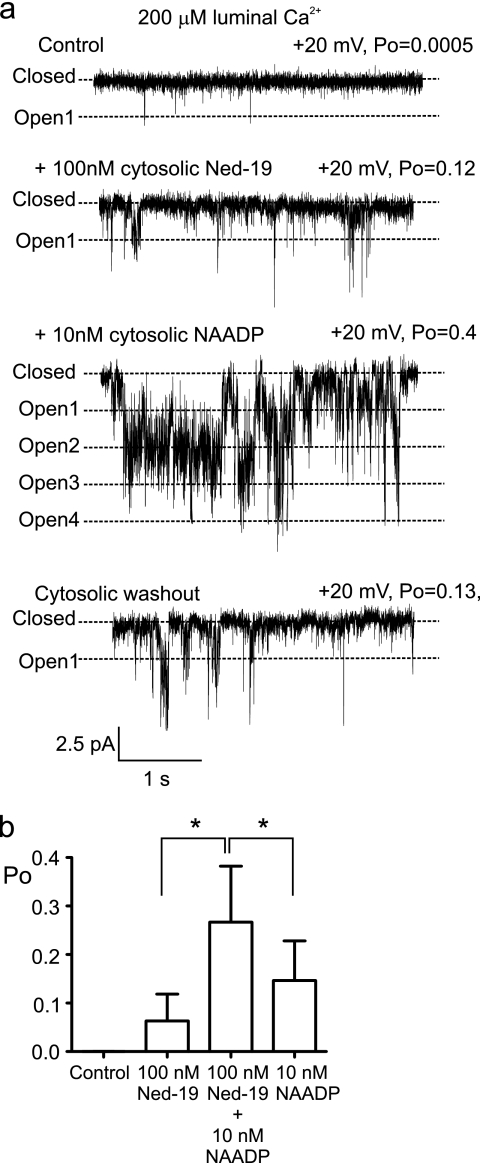

In the absence of NAADP, Ned-19 can activate TPC2 at nanomolar concentrations, as shown in Fig. 7a. Subsequent addition of NAADP in the continued presence of Ned-19 (100 nm) caused further channel activation. The histogram in Fig. 7b demonstrates that Ned-19 potentiates the effects of NAADP; the sum of the individual effects of 10 nm NAADP and 100 nm Ned-19 is less than the simultaneous action of 10 nm NAADP plus 100 nm Ned-19. In the absence of NAADP, at high concentrations (1 μm), Ned-19 closes the channel (see supplemental Fig. S3). We therefore show for the first time that Ned-19 is a high affinity activator of TPC2, that it closes the channel at high concentrations, and that, consistent with previous experiments measuring inhibition of NAADP-induced Ca2+ release in isolated membranes (21, 36), it is not a competitive inhibitor of NAADP.

FIGURE 7.

Ned-19 potentiates the effects of NAADP at TPC2. a, Ned-19 can activate TPC2 in the absence of NAADP. A typical experiment is shown where Ned-19 (100 nm) activates TPC2 in the absence of NAADP. Subsequent addition of NAADP potentiates the effects of Ned-19 (further evidence that NAADP and Ned-19 do not compete for the same binding sites). Washout of cytosolic NAADP and Ned-19 (bottom trace) lowers Po but to a level higher than that of the control (top trace). This is because although Ned-19 binding to TPC2 is reversible, NAADP binding to TPC2 is irreversible. b, comparison of the individual and simultaneous effects of NAADP and Ned-19 on TPC2 Po (*, p < 0.05).

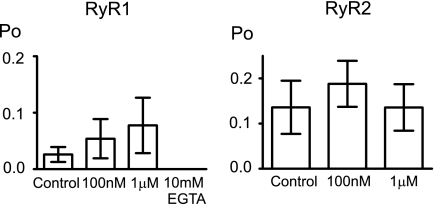

Our data strongly suggest that TPCs are the NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ release channels but do not rule out the possibility that RyR channels are also relevant NAADP receptors/Ca2+ release channels. With identical recording conditions, optimized for luminal Ca2+ potentiation of cytosolic ligands, we investigated the effects of NAADP on RyR2 and RyR1. Fig. 8 shows that concentrations up to 1 μm had no significant effects on the Po of either isoform, suggesting that RyR channels are unlikely to be involved in NAADP Ca2+-signaling processes other than by indirect recruitment subsequent to Ca2+ release via another pathway, as suggested previously (5, 29).

FIGURE 8.

Effects of NAADP on RyR. Histograms showing the effect of NAADP on RyR1 and RyR2 with Ca2+ as the permeant ion (mean ± S.D.; n ≥ 3) are displayed. The Ca2+ sensitivity of RyR1 was checked at the end of the experiment by lowering the cytosolic [Ca2+] to subactivating levels (<1 nm free Ca2+) with 10 mm cytosolic EGTA. All channel openings were abolished (Po = 0; n = 3). In separate bilayer experiments with RyR2 channels from the same preparations as those used in the histogram, the Ca2+ sensitivity was also confirmed with EGTA (10 mm).

DISCUSSION

Our TPC2 studies reveal a number of specific gating mechanisms that link clearly with some of the more unusual aspects of NAADP-induced Ca2+ release and that provide a biophysical picture of how TPC2 may be regulated in a cellular environment. These include extreme sensitivity to NAADP, which is finely controlled by the luminal [Ca2+]. Luminal pH also modulates Po and the rate of dissociation of NAADP from TPC2, vastly changing the shape of the NAADP concentration-response relationship to a graded bell-shaped curve. The delayed onset in NAADP-induced activation of TPC2 that we observe may serve to explain previous reports of time dependence or delays in NAADP effects (34, 37, 38), but it is difficult to reconcile with the idea of a simple, high affinity (NAADP is effective at 1 nm), bimolecular interaction between NAADP and TPC2. In this respect, we can draw parallels with another class of Ca2+ release channel, the RyRs and their interactions with ryanodine. Like NAADP, ryanodine also binds irreversibly to RyR with high affinity (Kd = 1.7 nm) (39–42). Also like NAADP, the rate of association of ryanodine can be very slow (at 0 mV, 1 μm ryanodine takes >1 min to modify gating).5 Ryanodine is thought to bind only to open RyR channels, and the rate of association has been demonstrated to be dependent on the concentration of ryanodine and on the holding potential (43, 44). A similar situation may operate for NAADP interactions with TPC2. NAADP may only bind to certain conformations of TPC2, perhaps one or more particular closed or open states. To explain the synchronized gating that is induced by NAADP, we must depart from the parallel with ryanodine, but we may still maintain our analogy with RyR channels. Multiple RyR channels have been shown to open and close in synchrony, and the term “coupled gating” was first coined to describe this effect (45). As for TPC2, coupled gating of RyR channels was originally proposed to be ligand-dependent (FK-506 binding protein-dependent), although the mechanism for this effect has not been elucidated (45). Coupled gating of TPC2 is also ligand-dependent. Both NAADP and Ned-19 induce coupled gating but, as for RyR channels, we do not yet understand the mechanism underlying such behavior. Coupled gating of TPC2 would enable significant flexibility of NAADP-mediated effects, allowing a small conductance channel to produce larger Ca2+ signals. The fact that Ned-19 influences TPC2 gating by binding at sites other than the NAADP binding sites again shows parallels with other intracellular Ca2+ release channels. Both RyRs and IP3Rs possess various binding sites for a wide range of ligands, and this enables complex but flexible systems of Ca2+ release that can be fine-tuned to suit a diversity of biological processes.

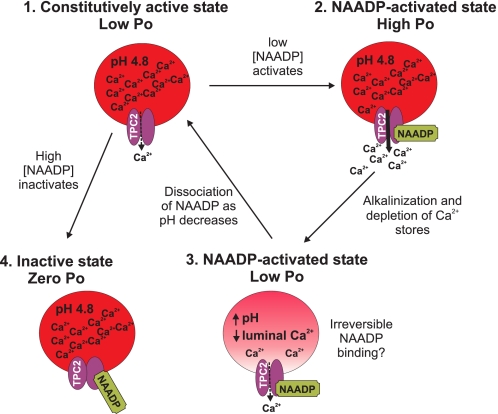

Fig. 9 incorporates our biophysical data into a predictive model of the regulation of TPC2 as the Ca2+ release channel of lysosome-like acidic Ca2+ stores. In the absence of activating ligands, TPC2 channels gate with very occasional brief openings (Po < 0.0009). We term this gating state of TPC2 the “constitutively active state.” Low concentrations of NAADP increase TPC2 Po, but this is characterized by (i) a delay in onset, (ii) frequent episodes of synchronized gating of multiple channels, and (iii) irreversible activation at pH 7.2 (on the timescale of a single-channel experiment). We term this gating state of TPC2 the “NAADP-activated state.” Thus, the rate of association of NAADP to TPC2 is slow, and the rate of dissociation of NAADP from TPC2 is even slower. The association rate does not appear to increase with either increases in luminal [Ca2+] or a change in pH but is concentration-dependent, being faster at 10 μm NAADP than at 10 nm NAADP as expected for a ligand-receptor interaction. At acidic pH (4.8), the rate of dissociation of NAADP from TPC2 is increased (NAADP binding to TPC2 is no longer irreversible). In contrast to the effects of low concentrations of NAADP, high concentrations of NAADP (1 mm) abolish even constitutive activity, and we term this state of TPC2 the “inactivated state.” The effects of high [NAADP] appear to be of rapid onset, but this is difficult to quantify because constitutive activity is so low.

FIGURE 9.

Model summarizing NAADP modulation of TPC2 channel gating. Without NAADP present, TPC2 Po is very low, but it still gates with occasional brief openings, and therefore, it is in a constitutively active state (1). Low [NAADP] increases Po to optimum levels when Ca2+ loading of the stores is high (2). Ca2+ release depletes the stores of Ca2+, leading to a reduced Po, but causes alkalinization within the stores, which could lead to irreversible binding of NAADP to TPC2 (3). Both state (2) and state (3) represent NAADP-activated states. As the acidic pH is restored, NAADP dissociates from TPC2, and luminal Ca2+ stores are replenished. High [NAADP] inactivates the channel (Po = 0) in a reversible manner (4); we term this state the inactive state.

We have reconstituted immunopurified TPC2 into artificial membranes. How do our single-channel currents compare with the currents measured from whole lysosomes isolated from HEK293 cells overexpressing TPC2 (13)? We demonstrate a Ca2+/K+ permeability ratio (PCa2+/PK+) of 2.6 and show, in many single-channel traces, that TPC2 is permeable to K+. In contrast, Schieder et al. (13) conclude that TPC2 is impermeable to K+. However, it is possible that these authors were unable to accurately measure PCa2+/PK+ due to a gating mechanism that inactivated the channels (13). With whole lysosome current recordings, it is difficult to determine whether a rectifying current is obtained because the channels are open but impermeable to K+ or whether the channels are shut due to a gating mechanism (inactivation or block). We have demonstrated that the luminal environment of TPC2 plays an important regulatory role. Perhaps there are additional luminal factors present within a lysosome that can affect TPC2 gating.

In summary, purified TPC2 behaves as a functional ion channel and, crucially, possesses the conduction properties required of an intracellular Ca2+ release channel. TPC2 also exhibits a number of unusual gating characteristics that provide an underlying explanation for many of the peculiarities of NAADP-induced Ca2+ release in cellular systems (9, 46) including extreme sensitivity to low concentrations of NAADP, inhibition by 1 μm Ned-19 and by high [NAADP], and time-dependent NAADP actions (38). A key aspect of TPC2 regulation is that the sensitivity and reversibility of NAADP binding are controlled by the luminal pH and [Ca2+]. Further investigation into the detailed gating mechanisms by which NAADP and other agents can regulate TPC channels will be an exciting area for future research that will transform our understanding of cellular NAADP-mediated processes.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation (to R. S.) and the Wellcome Trust (to A. G. and J. P.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental text and references and Figs. 1–3.

R. Sitsapesan, unpublished data.

- NAADP

- nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- TPC

- two-pore channel

- RyR

- ryanodine receptor

- IP3R

- inositol trisphosphate receptor

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- pS

- picosiemens.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee H. C., Aarhus R. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 2152–2157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee H. C. (2000) J. Membr. Biol. 173, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Genazzani A. A., Galione A. (1997) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 18, 108–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guse A. H. (2009) Curr. Biol. 19, R521–R523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel S., Churchill G. C., Galione A. (2001) Trends Biochem. Sci. 26, 482–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guse A. H., Lee H. C. (2008) Sci. Signal. 1, re10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galione A., Evans A. M., Ma J., Parrington J., Arredouani A., Cheng X., Zhu M. X. (2009) Pflugers Arch. 458, 869–876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Churchill G. C., Okada Y., Thomas J. M., Genazzani A. A., Patel S., Galione A. (2002) Cell 111, 703–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruas M., Rietdorf K., Arredouani A., Davis L. C., Lloyd-Evans E., Koegel H., Funnell T. M., Morgan A. J., Ward J. A., Watanabe K., Cheng X., Churchill G. C., Zhu M. X., Platt F. M., Wessel G. M., Parrington J., Galione A. (2010) Curr. Biol. 20, 703–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calcraft P. J., Ruas M., Pan Z., Cheng X., Arredouani A., Hao X., Tang J., Rietdorf K., Teboul L., Chuang K. T., Lin P., Xiao R., Wang C., Zhu Y., Lin Y., Wyatt C. N., Parrington J., Ma J., Evans A. M., Galione A., Zhu M. X. (2009) Nature 459, 596–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brailoiu E., Churamani D., Cai X., Schrlau M. G., Brailoiu G. C., Gao X., Hooper R., Boulware M. J., Dun N. J., Marchant J. S., Patel S. (2009) J. Cell Biol. 186, 201–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tugba Durlu-Kandilci N., Ruas M., Chuang K. T., Brading A., Parrington J., Galione A. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 24925–24932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schieder M., Rötzer K., Brüggemann A., Biel M., Wahl-Schott C. A. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 21219–21222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishibashi K., Suzuki M., Imai M. (2000) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 270, 370–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zong X., Schieder M., Cuny H., Fenske S., Gruner C., Rötzer K., Griesbeck O., Harz H., Biel M., Wahl-Schott C. (2009) Pflugers Arch. 458, 891–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clapham D. E., Garbers D. L. (2005) Pharmacol. Rev. 57, 451–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pitt S. J., Funnell T., Zhu M. X., Sitsapesan M., Venturi E., Parrington J., Ruas M., Galione A., Sitsapesan R. (2010) Biophys. J. 98, 682a–683a [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sitsapesan R., Montgomery R. A., MacLeod K. T., Williams A. J. (1991) J. Physiol. 434, 469–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colquhoun D., Sigworth F. J. (1983) in Single-channel recording (Sakmann B., Neher E. eds.) 2nd Ed., pp. 483–587, Plenum Publishing Corp., New York [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fatt P., Ginsborg B. L. (1958) J. Physiol. 142, 516–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naylor E., Arredouani A., Vasudevan S. R., Lewis A. M., Parkesh R., Mizote A., Rosen D., Thomas J. M., Izumi M., Ganesan A., Galione A., Churchill G. C. (2009) Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 220–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindsay A. R., Williams A. J. (1991) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1064, 89–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bezprozvanny I., Ehrlich B. E. (1994) J. Gen. Physiol. 104, 821–856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tinker A., Williams A. J. (1992) J. Gen. Physiol. 100, 479–493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ehrlich B. E., Watras J. (1988) Nature 336, 583–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Churchill G. C., Galione A. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 38687–38692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kinnear N. P., Boittin F. X., Thomas J. M., Galione A., Evans A. M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 54319–54326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kinnear N. P., Wyatt C. N., Clark J. H., Calcraft P. J., Fleischer S., Jeyakumar L. H., Nixon G. F., Evans A. M. (2008) Cell Calcium 44, 190–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cancela J. M., Churchill G. C., Galione A. (1999) Nature 398, 74–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morgan A. J., Galione A. (2008) Methods 46, 194–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sitsapesan R., Williams A. J. (1994) J. Membr. Biol. 137, 215–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lukyanenko V., Györke I., Györke S. (1996) Pflugers Arch. 432, 1047–1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lloyd-Evans E., Morgan A. J., He X., Smith D. A., Elliot-Smith E., Sillence D. J., Churchill G. C., Schuchman E. H., Galione A., Platt F. M. (2008) Nat. Med. 14, 1247–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Churchill G. C., Galione A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 11223–11225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morgan A. J., Galione A. (2007) Biochem. J. 402, 301–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosen D., Lewis A. M., Mizote A., Thomas J. M., Aley P. K., Vasudevan S. R., Parkesh R., Galione A., Izumi M., Ganesan A., Churchill G. C. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 34930–34934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Churamani D., Dickinson G. D., Ziegler M., Patel S. (2006) Biochem. J. 397, 313–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Genazzani A. A., Empson R. M., Galione A. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 11599–11602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sutko J. L., Airey J. A., Welch W., Ruest L. (1997) Pharmacol. Rev. 49, 53–98 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sutko J. L., Airey J. A. (1996) Physiol. Rev. 76, 1027–1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rousseau E., Smith J. S., Meissner G. (1987) Am. J. Physiol. 253, C364–C368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buck E., Zimanyi I., Abramson J. J., Pessah I. N. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 23560–23567 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lindsay A. R., Tinker A., Williams A. J. (1994) J. Gen. Physiol. 104, 425–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chu A., Díaz-Muñoz M., Hawkes M. J., Brush K., Hamilton S. L. (1990) Mol. Pharmacol. 37, 735–741 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marx S. O., Ondrias K., Marks A. R. (1998) Science 281, 818–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bak J., Billington R. A., Genazzani A. A. (2002) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 295, 806–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saftenku E., Williams A. J., Sitsapesan R. (2001) Biophys.J. 80, 2727–2741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.