Abstract

We identified that activation of the Gq-linked dopamine D1-D2 receptor hetero-oligomer generates a PLC-dependent intracellular calcium signal. Confocal FRET between endogenous dopamine D1 and D2 receptors in striatal neurons confirmed a physical interaction between them. Pretreatment with SKF 83959, which selectively activates the D1-D2 receptor heteromer, or SKF 83822, which only activates the D1 receptor homo-oligomer, led to rapid desensitization of the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-mediated calcium signal in both heterologous cells and striatal neurons. This desensitization response was mediated through selective occupancy of the D1 receptor binding pocket. Although SKF 83822 was unable to activate the D1-D2 receptor heteromer, it still permitted desensitization of the calcium signal. This suggested that occupancy of the D1 receptor binding pocket by SKF 83822 resulted in conformational changes sufficient for desensitization without heteromer activation. Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer and co-immunoprecipitation studies indicated an agonist-induced physical association between the D1-D2 receptor heteromeric complex and GRK2. Increased expression of GRK2 led to a decrease in the calcium signal with or without prior exposure to either SKF 83959 or SKF 83822. GRK2 knockdown by siRNA led to an increase in the signal after pretreatment with either agonist. Expression of the catalytically inactive and RGS (regulator of G protein signaling)-mutated GRK2 constructs each led to a partial recovery of the GRK2-attenuated calcium signal. These results indicated that desensitization of the dopamine D1-D2 receptor heteromer-mediated signal can occur by agonist occupancy even without activation and is dually regulated by both the catalytic and RGS domains of GRK2.

Keywords: Calcium Intracellular Release, G Protein-coupled Receptors (GPCR), G Proteins, Phospholipase C, Receptor Desensitization, D1 Dopamine Receptor, D2 Dopamine Receptor, G Protein-coupled Receptor Kinase 2, Hetero-oligomer

Introduction

The neurotransmitter dopamine has fundamental roles in regulating a wide variety of neuronal functions such as locomotion, cognition, reward, and emotion. Dysregulation of this system in brain has been implicated in a number of pathological conditions such as schizophrenia, drug addiction, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and Parkinson disease (1). The dopamine receptors are members of the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR)3 superfamily with the D1 and D2 receptors being the most abundant subtypes. The major signaling pathway of the D1 receptor is stimulation of adenylyl cyclase (AC) via activation of Gs and Golf proteins, whereas the D2 receptor primarily signals through Gi or Go proteins to inhibit AC. Although the D1 and D2 receptors have opposing signaling effects on AC function, these receptors when co-activated have demonstrated functional synergism (2–4), which may result from activity of neurons co-expressing D1 and D2 receptors (5–8). Similar to most GPCRs, dopamine receptors have been demonstrated to exist as homo-oligomers and hetero-oligomers (9–12). Hetero-oligomerization of D1 and D2 receptors may be responsible for some of the D1-D2 receptor synergistic effects. We have previously demonstrated that D1 and D2 receptors form functional hetero-oligomeric complexes in cells and in vivo (8, 13, 14). Activation of this D1-D2 receptor heteromer in cells and in striatal neurons results in a Gq/11 protein-linked phospholipase C (PLC)-mediated intracellular calcium signal that was not activated by either homo-oligomer alone.

Because activation of these D1-D2 receptor complexes results in calcium signaling, it is then important to determine how this signal is regulated. Although much is known about how signals generated from D1 and D2 receptor homo-oligomers are regulated, the regulation of the D1-D2 receptor heteromer remains to be elucidated. Termination of the signal by receptor desensitization is an important component of GPCR signaling. We have previously demonstrated that pretreatment of the D1-D2 receptor heteromer with dopamine results in rapid desensitization of the D1-D2 receptor-mediated calcium signal (15). This desensitization was demonstrated to occur specifically through a homologous mechanism and was independent of intracellular calcium store depletion, suggesting the calcium signal desensitization might occur at the level of the receptor complex. To study potential mediators of D1-D2 receptor heteromer calcium signal desensitization, we previously tested the involvement of several second messenger kinases, but only G protein-coupled receptor kinases 2 or 3 (GRKs 2 or 3) were shown to play a role (15). We have specifically identified that the agonist, SKF 83959, selectively activated the D1-D2 receptor heteromer, whereas SKF 83822 only activated the D1 homo-oligomer, and SKF 81297 activated both the D1 and D1-D2 receptor complexes (13).

In this study we investigated the desensitization of the D1-D2 receptor heteromer calcium signal resulting from receptor occupancy by these agonists that all have equivalent ability to bind with high affinity to the D1 receptor but exhibit differential abilities to activate the D1-D2 receptor heteromeric pathway. We demonstrated that pretreatment with any of the three agonists resulted in rapid desensitization of the calcium signal both in cells and in primary culture neurons, and this was shown to occur through selective occupancy of the D1 receptor. Intriguingly, occupancy of the D1 receptor binding pocket by SKF 83822 that was unable to activate the D1-D2 receptor complex still permitted desensitization of the calcium response, suggesting that activation of the receptor was not a prerequisite and occupancy of the receptor binding pocket with its associated conformational changes was sufficient to lead to desensitization.

We also provided evidence for a direct interaction between GRK2 and the D1-D2 receptor heteromer. We examined the role of GRK2 by assessing the relative contribution of distinct functional domains within GRK2 responsible for terminating D1-D2 receptor heteromer signaling. Our results suggested that both the catalytic domain of GRK2 as well as the RGS domain through its ability to interact with the Gq protein played a role in inhibiting D1-D2 receptor heteromer signaling after receptor activation. This demonstrated a distinct form of regulation for the D1-D2 receptor hetero-oligomer different from that of D1 and D2 receptor homo-oligomeric units where this dual function involving both the catalytic and RGS domains of GRK2 in inhibiting signaling has not been reported.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Measurement of the Calcium Signal in HEK 293 Cells

Cell culture was performed as previously described (8). Briefly, stable cell lines co-expressing the amino-terminal hemagglutinin epitope-tagged human D1 receptor and amino-terminal FLAG epitope-tagged human D2 receptor were created in HEK293TSA cells using the bicistronic pBudCE 4.1 vector. All cell culture and transfection reagents were obtained from Invitrogen. HEK293TSA cells were maintained as monolayer cultures at 37 °C in advanced minimum essential medium supplemented with 6% fetal bovine serum, 300 μg/ml Zeocin, and antibiotic-antimycotic. Calcium mobilization assays were carried out using a Flex station multiwell plate fluorometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Stably transfected cells were seeded in black microtiter plates at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells/well grown for 24 h. The cells were then loaded with 2 μm Fluo-4 acetoxymethyl ester indicator dye (Invitrogen) in advanced minimum essential medium supplemented with 2.5 mm probenecid (Sigma) for 1 h and subsequently washed twice with Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) and supplemented with 20 mm HEPES (Invitrogen). Base-line fluorescence values were measured for 15 s, and changes in fluorescence corresponding to alterations in intracellular calcium levels upon the addition of agonists thereafter were recorded. Fluorescence values were collected at 3-s intervals for 100 s, and the difference between maximum and minimum fluorescence values for each agonist concentration was determined and analyzed using Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). For desensitization studies, cells were pretreated with agonists in serum-free advanced minimum essential medium in a dose- and time-response manner and washed off with HBSS before calcium measurement. For inhibitor studies, cells were pretreated with 10 μm SQ 22536 1 h before agonist pretreatment or 10 μm SCH 23390 or raclopride 10 min before agonist pretreatment. SKF 81297, SKF 83959, SKF 83822, dopamine, quinpirole, SCH 23390, raclopride, ATP, EGTA, H-89, and SQ 22536 were purchased from Sigma. For studies involving GRKs, transient transfections of cDNA encoding GRK2, K220R-GRK2, D110A-GRK2, or R106A/K220R-GRK2 in the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) or GFP-GRK2 in the mammalian expression vector pEGFP-N were performed with Lipofectamine (Invitrogen). The GRK constructs were kind gifts from Dr. Jeffrey Benovic (Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA).

Small Interfering RNA Silencing of Gene Expression

Chemically synthesized double-stranded small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes (with 3′-dTdT overhangs) were purchased from Qiagen Inc. (Mississauga, ON, Canada). GRK2 siRNA (5′-AAGAAGUACGAGAAGCUGAG-3′) and a nonsilencing RNA duplex (5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGU-3′) that was used as a control for the siRNA experiments was validated elsewhere (44). The HEK 293 cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The final concentration of siRNA was 40 nm. The effect of siRNA transfection was assessed by immunoblotting. Average silencing for these experiments was 69% of basal levels.

Membrane Preparation and Radioligand Binding Assay

D1-D2 receptor-expressing cells were first treated with either vehicle or 100 nm SKF 83959 in advanced minimum essential medium supplemented with 2.5 mm probenecid for 30 min at 4 °C. The cells were then washed twice in cold HBSS with probenecid and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C to obtain a pellet. Cell lysates were prepared by disruption with a Polytron homogenizer (Kinematica, Basel, Switzerland) in ice-cold 5 mm Tris-HCl and 2 mm EDTA buffer containing protease inhibitors (5 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml benzamidine, and 5 μg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor). Lysates were centrifuged at 800 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected. Membrane fractions were prepared by centrifuging the supernatant at 13000 rpm for 20 min. Membrane protein was determined by the Bradford assay according to the manufacturer's instructions (Bio-Rad). Saturation binding assays were performed in 1 ml of binding buffer with 35 μg of membrane homogenate and increasing concentrations (0.05 to 4 nm) of [3H]SCH 23390. Nonspecific binding was determined by 10 μm (+)-butaclamol. Incubation was performed for 2 h at room temperature. At the end of the incubation, bound ligand was isolated by rapid filtration through a 48-well cell harvester (Brandel, Montreal, QC, Canada) using Whatman GF/C filters (Whatman, Clifton, NJ). Data were analyzed by nonlinear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism for the determination of dissociation constants (Kd) and the density of receptors (Bmax).

Neuronal Cultures

Neuronal cultures derived from post-natal day 1 rodent striatum were trypsinized in HBSS with 0.25% trypsin and 0.05% DNase (Sigma) at 37 °C and then washed 3 times in HBSS with 12 mm MgSO4. Cells were dissociated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 2 mm glutamine and 10% FBS and plated at 2 × 105 cells per poly-l-lysine-coated wells (Sigma; 50 μg/ml). After 24 h the media was replaced with neurobasal medium with 50× B27 supplement and 2 mm glutamine (Invitrogen). After 3 days in culture, cytosine arabinoside was added (5 μm) to inhibit glial cell proliferation. Half of the medium was changed every 3 days. The neurons were in culture for 7–14 days before experiments were performed. Cell viability was tested with trypan blue (0.4%) (Invitrogen) exclusion and indicated 2% cell death.

Immunocytochemistry

The primary antibodies used were rat anti-D1 (Sigma, 1:400) and rabbit anti-D2 (Millipore, Billerica, MA; 1:400). The secondary antibodies, conjugated to fluorophores Alexa Fluor 568 and Alexa Fluor 647 (Invitrogen), were used at 1:500. Paraformaldehyde-fixed neurons were incubated with the primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. After 3 washes with PBS-Tween 20, the samples were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody for 2–4 h at room temperature. After three washes, the slides were mounted using a mounting solution (Dako, Carpinteria, CA), and the images were acquired using a confocal Fluoview Olympus microscope (FV 1000). All images were acquired in sequential mode to minimize any bleed-through. For GRK2 studies, the neurons were pretreated with 100 nm dopamine, SKF 83959, or SKF 83822 for 5 min and then washed twice with PBS before fixing with paraformaldehyde. The primary antibody used was rabbit anti-GRK2 (Sigma, 1:200), and the secondary antibody was conjugated to Alexa 350 (Invitrogen).

Confocal Microscopy FRET

Paraformaldehyde-fixed striatal neurons from rat brain were incubated for 24 h at 4 °C with primary antibodies highly specific to D1 and D2 receptors (8) and the species-specific secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa 350 and Alexa 488 dyes. The primary antibodies have been shown to be highly specific to D1 or D2 receptors using HEK cells expressing individual D1, D2, D3, D4, or D5 receptors (8). They were further validated by immunohistochemistry showing a lack of reactivity in slices from D1−/− and D2−/− mice. Anti-D2-Alexa 350 and anti-D1-Alexa 488 were used as the donor and acceptor dipoles, respectively. An Olympus Fluoview FV 1000 laser-scanning confocal microscope with a 60×/1.4 NA objective was used to obtain the images. A krypton laser at 405 nm and an argon laser at 488 nm was used to excite the donor and acceptor, respectively. The emissions were collected at 430 and 530 nm LP filter. Other FRET pairs (488–568 and 568–647) were tested and showed comparable results. Each FRET analysis was performed using 11 images and calculated using an algorithm (16). The corrected FRET (cFRET) images were then generated based on the described algorithm in which cFRET = UFRET − ASBT − DSBT, where UFRET is uncorrected FRET, and ASBT and DSBT are the acceptor and the donor spectral bleed-through signals. Small regions of interest using the same images and software were used to estimate the rate of energy transfer efficiency (E) and the distance (r) between the donor (D) and the acceptor (A) molecules in accordance with the equation E = 1 − IDA/[IDA + pFRET((ψdd/ψaa)(Qd/Qa))], where IDA is the donor image in the presence of acceptor, ψdd and ψaa are collection efficiencies in the donor and acceptor channels, and Qd and Qa are the quantum yields. E is proportional to the 6th power of the distance (r) separating the FRET pair. r = Ro [(1/E) − 1]1/6, Ro is Förster's distance.

Measurement of the Calcium Signal in Primary Striatal Neurons

Calcium mobilization was measured in neonatal neurons in culture using cameleon YC6.1 (17), an engineered calcium indicator based on the conformational change of a calmodulin peptide flanked by two fluorophores, CFP and YFP. An increase in calcium binding to calmodulin leads to a decrease in the distance separating the two flanking proteins, CFP and YFP, and results in a measurable FRET change. The cameleon was a generous gift from Dr. M. Ikura, University of Toronto. The striatal neuronal cultures were transfected with cameleon YC6.1 using a combination of Effectene (Qiagen) and ExgenTM500 (Fermentas, Burlington, ON, Canada) that resulted in a transfection efficiency of 40–70%. Briefly, 2.7 μg of cameleon YC6.1 cDNA was mixed with Buffer EC (Effectene kit), 150 mm NaCl, and Exgen reagent and enhancer and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Subsequently, Effectene reagent was added and mixed. Ten minutes later 6 ml of culture media was added to the mixture, which was split into 24 wells. Treatment with trypan blue (0.4%) indicated that cell death was ∼10% after transfection. The experiments were then performed in these live neurons transfected with cameleon in the absence of extracellular calcium. Using a single excitation wavelength at 405 nm, which solely excites CFP, images and fluorescence emissions data for both CFP and YFP were collected, and energy transfer was calculated (14). Activation of the calcium signal was measured after treatment with either 100 nm dopamine, SKF 83959, or SKF 83822. The background signal was subtracted from the values obtained after drug injection. For desensitization studies, the neurons were pretreated with agonists in HBSS for 30 min and washed off with the same media before calcium measurement. For inhibitor studies, the neurons were pretreated with 10 μm SQ22536 or H-89 for 30 min before agonist pretreatment. For siRNA experiments, the neurons were transfected in cultured medium using Hiperfect transfection reagent (Qiagen). The neurons were transfected with either GRK2 siRNA or a non-silencing siRNA as per the manufacturer's instructions. The siRNA final concentration was 100 nm. The effect of siRNA transfection was assessed by Western blotting analysis. Average silencing for these experiments was 70% of basal levels.

Immunoprecipitation

HEK 293 cells stably expressing both the HA epitope-tagged D1 receptor and FLAG epitope-tagged D2 receptor were transfected with 2 μg of GRK2 cDNA followed by treatment with 1 μm dopamine, SKF 83959, or SKF 83822 for 5 min. 75 μl of anti-FLAG M2-agarose (Sigma) was used to immunoprecipitate the FLAG-D2 receptor from a P2 membrane fraction of these HEK 293 cells. The P2 fraction was incubated with the antibody overnight at 4 °C. Agarose beads were collected and washed 4 times followed by an overnight incubation with 100 μg of a FLAG peptide at 4 °C to displace the anti-FLAG antibody from the D2 receptor. The proteins were resolved by gel electrophoresis. Immunodetection of the FLAG-D2 receptor from immunoprecipitates was detected with mouse anti-FLAG antibody (1:1000) (Sigma) and HA-D1 receptor, and GRK2 immunoreactivity were detected with rat anti-HA antibody (1:1000) (Roche Diagnostics) and rabbit anti-GRK2 antibody (1:1000) (Sigma), respectively.

BRET Assay

To detect an agonist-induced interaction between the D1-D2 receptor heteromer and GRK2, BRET studies were performed on HEK 293 cells transfected with 1 μg of Rluc-tagged D1 receptor, FLAG-D2 receptor, and GFP-tagged GRK2 or GFP cDNA. Cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 105 cells/well for 24 h and then treated with 1 μm dopamine, SFK 83959, SKF 83822 for 1–10 min. After the induction of Rluc-mediated light emission by the addition of the substrate coelenterazine h (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) emission was measured using a plate-reader spectrofluorometer (Victor3, PerkinElmer Life Sciences) at wavelengths 480 and 535 nm, corresponding to the maxima of the emission spectra for Rluc and GFP, respectively. The BRET ratio was calculated using the equation previously described (18). The background BRET signal from Rluc-D1 receptor to GFP was subtracted from the BRET signal obtained from Rluc-D1 receptor to GFP-GRK2.

SDS-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis and Immunoblotting

The procedures used for protein gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting were identical to those described previously (10). Rabbit anti-GRK2 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, Santa Cruz, CA) was used at 1:1000 dilution to assess overexpression of GRK2 and 1:600 to measure silencing of GRK2. Rabbit anti-GAPDH (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was used at a 1:7500 dilution.

RESULTS

Activation and Desensitization of the D1-D2 Receptor Heteromer-mediated Calcium Signal in HEK Cells

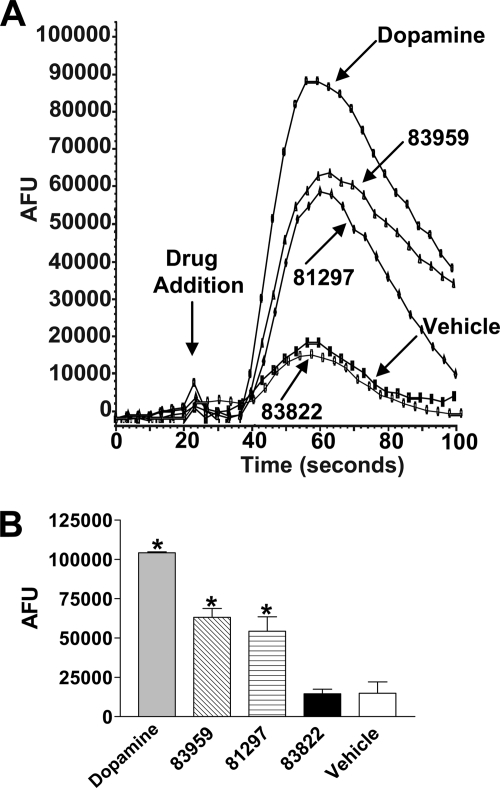

To study the effects of the agonists on the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-mediated calcium signal, we first confirmed the abilities of each agonist to activate the intracellular calcium signal in a stable cell line coexpressing D1 and D2 receptors (8) in the presence of EGTA, an extracellular calcium chelator. The cells expressed D1 and D2 receptors in a 1:1 ratio with final receptor densities of ∼0.8 pmol/mg of protein. The addition of either dopamine, SKF 83959, the agonist that selectively triggers PI hydrolysis, or SKF 81297, the agonist that activates both AC and PI turnover, stimulated a robust calcium signal that peaked within 20–40 s of agonist activation and declined within 120 s, compared with vehicle as shown in a representative tracing (Fig. 1A) or the peak heights of the calcium signals (Fig. 1B). The addition of SKF 83822, the agonist that has been shown to only activate AC, did not elicit a significant calcium signal (Fig. 1, A and B).

FIGURE 1.

Specificity of dopamine receptor agonists activating the D1-D2 receptor heteromer calcium signal in cells stably expressing the D1 and D2 receptors. A, representative tracings display changes in fluorescence corresponding to changes in intracellular calcium levels on treatment of D1 and D2 receptors with 1 μm concentrations of dopamine, SKF 83959, SKF 81297, SKF 83822, or vehicle. AFU, absolute fluorescence units. B, shown are peak heights of agonist-induced calcium release through activation of the D1-D2 receptor heteromer. Values shown are the means ± S.E. of n = 3 experiments. A significant difference from vehicle is denoted by * = p < 0.05.

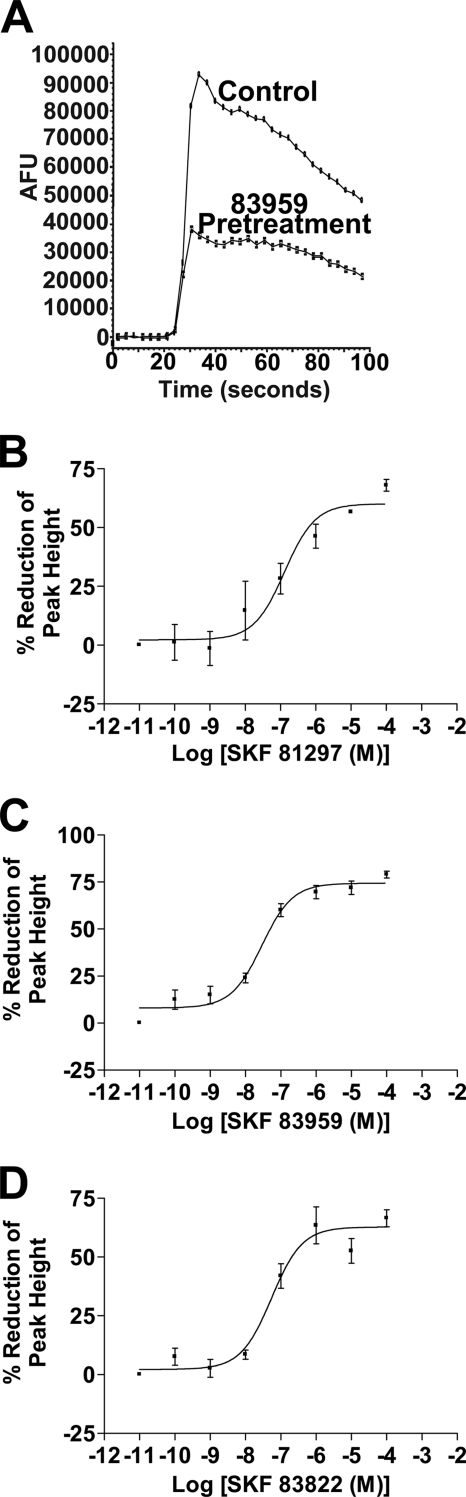

To investigate calcium signal desensitization, the cells were pretreated for 5 min with increasing concentrations of each agonist, from 10−11 to 10−4 m, which was washed off followed by subsequent activation with 10 μm dopamine. All three agonists by prior exposure were able to significantly desensitize the calcium signal to dopamine activation (60.1 ± 2.8% reduction for SKF 81297 (n = 3), 74.4 ± 2.2% reduction for SKF 83959 (n = 5), and 62.8 ± 2.8% reduction for SKF 83822 (n = 8)). SKF 83959 was the most potent in desensitizing the signal (EC50 = 29.1 ± 0.5 nm) followed by SKF 83822 (EC50 = 54.7 ± 1.2 nm), and the least potent was SKF 81297 (EC50 = 130.9 ± 4.1 nm) (Fig. 2, A–D). The potency of the agonists to induce desensitization and the extent of desensitization of the calcium signal after agonist exposure for 10 or 30 min was similar to that seen after agonist exposure for 5 min (data not shown). No significant difference in the extent of desensitization was seen in the presence of 250 μm EGTA, indicating no involvement of extracellular calcium (data not shown). To demonstrate that depletion of intracellular calcium stores by prolonged agonist treatment was not the mediator of this calcium signal desensitization, endogenously expressed purinergic receptors, which also use the Gq protein and PLC as a means to generate calcium release through intracellular stores (19), were activated with 10 μm ATP after dopamine agonist pretreatment in the presence of EGTA. No significant difference in the extent of the ATP-mediated calcium signal was observed after pretreatment with SKF 83959 (for 30 min) compared with control as determined by their peak heights, suggesting that calcium stores were not significantly depleted after dopamine agonist pretreatment (peak absolute fluorescence units (AFU) = 136,051 ± 4,373 for control and peak AFU = 141,608 ± 4,722 for cells pretreated with SKF 83959 (n = 3)). To demonstrate that the desensitization of the calcium signal was not due to residual agonist persistently occupying the ligand binding pocket of the receptor, saturation binding studies were carried out after the D1-D2 receptor-expressing cells were treated with 100 nm SKF 83959 for 30 min. The Bmax and Kd values for [3H]SCH 23390 binding were 0.892 ± 0.17 pmol/mg of protein and 277 ± 9.6 pm for the control cells not pretreated with agonist and 0.875 ± 0.13 pmol/mg of protein and 308 ± 11 pm (n = 4) for cells pretreated with SKF 83959. These results indicated that there was no persistent occupancy of the ligand binding pocket after agonist wash off. Because SKF 83822 was not able to significantly activate the calcium signal but still led to its desensitization, the involvement of a heterologous mechanism involving the AC pathway was investigated. When cells were pretreated with SKF 83822 in the absence and presence of the AC inhibitor, SQ 22536, there was no significant difference in the extent of the calcium signal (47.5 ± 4.6% reduction for cells treated with SKF 83822 and 41.3 ± 6.2% reduction for cells treated with SKF 83822 and SQ 22536 (n = 4)), suggesting the desensitization mediated by SKF 83822 did not involve AC. Taken together, these results demonstrated that although SKF 83959 and SKF 83822 have differential abilities to activate the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-mediated calcium signal, both were able to elicit significant calcium signal desensitization.

FIGURE 2.

The D1-D2 receptor heteromer-mediated calcium signal is desensitized by prior treatment with dopamine agonists for 5 min. A, representative calcium tracings displaying the calcium signal activated by 10 μm dopamine (control) and after pretreatment with 1 μm SKF 83959 for 5 min in D1-D2 receptor stably expressing cells. Dose-response curves demonstrate the percentage reduction in peak calcium levels after pretreatment with increasing concentrations of SKF 81297 (B), SKF 83959 (C), or SKF 83822 (D) from 10−11 to 10−4 m for 5 min, washed, and activated with 10 μm dopamine. Values shown are the means ± S.E. of n = 3–6 experiments.

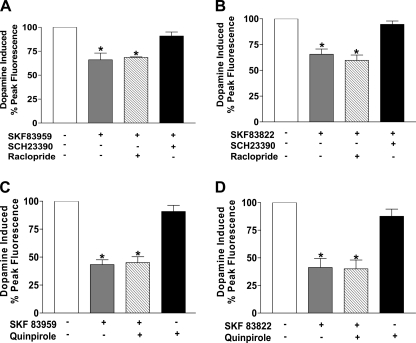

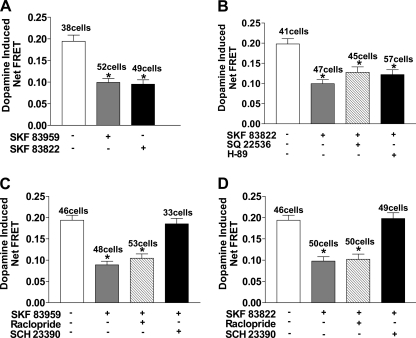

Because SKF 83959 acts as a full agonist for the D1 receptor and a partial agonist for the D2 receptor within the D1-D2 receptor complex (13), the desensitization observed could potentially be mediated by occupancy of both receptors. To investigate whether both D1 and D2 receptors were involved in the desensitization of the signal, a D2 selective antagonist, raclopride, 10 μm, was added with SKF 83959 or SKF 83822 pretreatment for 30 min and then washed off followed by activation with 10 μm dopamine. No significant difference in the extent of desensitization caused by SKF 83959 or SKF 83822 was observed in the presence of raclopride (Fig. 3, A and B). However, the desensitization induced by each drug was abolished by pretreatment with the D1 antagonist, SCH 23390, 10 μm. Similar results were obtained for the agonist, SKF 81297 (data not shown). These results suggested that the desensitization elicited by each agonist occurred through selective occupancy of the D1 receptor. To further confirm the observed desensitization was through occupancy of the D1 receptor rather than the D2 receptor, the cells were pretreated with both a D1 agonist and the D2 agonist, quinpirole, for 30 min and then washed off followed by a subsequent challenge with dopamine. No significant difference in the extent of desensitization was observed, suggesting that occupancy of the D1 and D2 receptors concurrently did not enhance desensitization of the signal (Fig. 3, C and D). Pretreatment with quinpirole alone did not induce any significant desensitization.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of dopamine receptor antagonists and D2 receptor agonist, quinpirole, on the desensitization of the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-mediated calcium signal in D1-D2 receptor stably expressing cells. Data are represented as the percentage of peak fluorescence of the dopamine induced calcium signal, and values are the means ± S.E. of the numbers shown in brackets below. Desensitization of the calcium signal elicited by dopamine after pretreatment with 1 μm SKF 83959 (A) or 1 μm SKF 83822 (B) for 30 min without or with pretreatment with 10 μm raclopride or 10 μm SCH 23390 (n = 4–6) is shown. C, shown is desensitization of the calcium signal elicited by dopamine after pretreatment with 1 μm SKF 83959 or 1 μm quinpirole or both SKF 83959 and quinpirole. D, shown is desensitization of the calcium signal elicited by dopamine after pretreatment with 1 μm SKF 83822 or 1 μm quinpirole or both SKF 83822 and quinpirole (n = 3–4). A significant difference from control is denoted by * = p < 0.05.

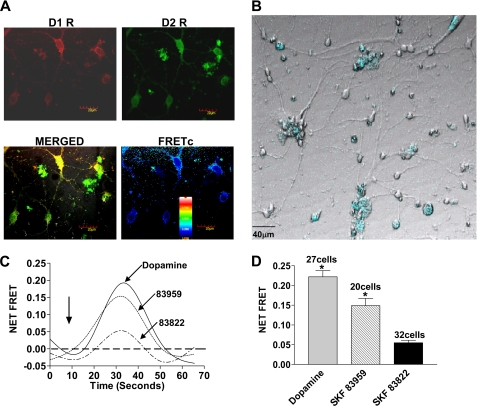

Activation and Desensitization of the D1-D2 Receptor-mediated Calcium Signal in Primary Striatal Neurons

D1 and D2 receptors were mainly expressed at the cell surface and on proximal neurites with a high degree of colocalization in postnatal striatal neurons as determined by immunocytochemistry (Fig. 4A). Localization of D2 receptors was also observed in the cytosol. Confocal FRET analysis of the natively expressed dopamine D1 and D2 receptors demonstrated a relative distance of 5–7 nm (50–70 Å) in localized membrane microdomains, thus, indicating a physical interaction between the natively expressed D1 and D2 receptors. FRET efficiency (E) ranged from 0.1 to 0.5, with a higher efficiency in the soma and proximal dendrites and lower in distal processes as shown in a representative figure (Fig. 4A). Cameleon was transfected into the striatal neurons and was used as an indicator for the calcium signal. The majority of cameleon was localized in the cell bodies as well as a small amount in the dendritic processes (Fig. 4B). In the absence of extracellular calcium, the addition of either 100 nm dopamine or SKF 83959 to the striatal neurons led to rapid increases in cameleon FRET, corresponding to a rise in intracellular calcium, as shown in a representative tracing (Fig. 4C) or the peak heights of the calcium signals (Fig. 4D). The FRET signal peaked within 10 s of agonist activation and declined within 50 s. In contrast, induction of calcium mobilization by SKF 83822 was minimal (Fig. 4, C and D). For desensitization studies, the neurons were pretreated with 100 nm SKF 83959 or SKF 83822 for 30 min and then washed off followed by subsequent activation with 100 nm dopamine. Pretreatment with either SKF 83959 or SKF 83822 led to a significant attenuation of the calcium signal peak heights (50.9 ± 0.01% of control for SKF 83959 and 48.8 ± 0.01% of control for SKF 83822) (Fig. 5A). The extent of desensitization was not significantly different when the neurons were pretreated with SKF 83822 in the presence or absence of either the AC inhibitor, SQ 22536, or the protein kinase A (PKA) inhibitor, H-89, suggesting a heterologous mechanism involving the AC or cAMP pathway was not responsible for the signal attenuation by SKF 83822 (Fig. 5B). Pretreatment with either inhibitor alone did not result in any significant difference in the calcium signal from that elicited by dopamine (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

Specificity of dopamine receptor agonists activating the D1-D2 receptor heteromer calcium signal in primary striatal neurons. A, immunocytochemistry shows endogenously expressed dopamine D1 and D2 receptor colocalization (merged) and interaction (corrected FRET (FRETc)). The inset shows the calibration for FRET efficiency. B, striatal neurons display the presence of transfected cameleon (blue). C, representative tracings of cameleon FRET result from intracellular calcium release from D1-D2 receptor heteromer activation by 100 nm dopamine or SKF 83959 but not SKF 83822. The arrow indicates the time point of drug addition. D, peak heights of agonist-induced cameleon FRET correspond to calcium release through activation of the D1-D2 receptor heteromer. The results shown represent the means ± S.E. of values from the number of cells shown. A significant difference from SKF 83822 is denoted by * = p < 0.05.

FIGURE 5.

The D1-D2 receptor heteromer-mediated calcium signal is desensitized in striatal neurons by prior treatment with dopamine agonists for 30 min. A, peak FRET levels correspond to rises in intracellular calcium by activation with 100 nm dopamine and after pretreatment with 100 nm SKF 83959 or 100 nm SKF 83822 for 30 min. B, peak FRET levels correspond to rises in intracellular calcium by activation with 100 nm dopamine and after pretreatment with 100 nm SKF 83822 without and with 10 μΜ SQ 22536 or 10 μΜ H-89. Peak FRET levels correspond to rises in intracellular calcium by activation with 100 nm dopamine and after pretreatment with 100 nm SKF 83959 (C) or 100 nm SKF 83822 (D) without and with 10 μm raclopride or 10 μm SCH 23390. The results shown represent the means ± S.E. of values from the number of cells shown. A significant difference from control (no pretreatment) is denoted by * = p < 0.05.

Because it was shown that SKF 83959 can occupy both the D1 and D2 receptors within the D1-D2 receptor complex (13), the desensitization observed may be mediated by occupancy of both receptors. To prevent agonist occupancy of the D2 receptor, a D2-selective antagonist, raclopride (10 μm), was added with SKF 83959 or SKF 83822 pretreatment for 30 min and then washed off followed by activation with 100 nm dopamine. No significant difference in the extent of desensitization with either SKF 83959 or SKF 83822 was observed in the presence of raclopride (Fig. 5, C and D). However, SKF 83959- and SKF 83822-mediated desensitization was abolished by pretreatment with the D1 antagonist, SCH 23390 (10 μm). These results suggested that the desensitization elicited by each agonist in these neurons occurred through selective occupancy of the D1 receptor.

Role of GRK2 in Regulating the D1-D2 Receptor Heteromer-mediated Calcium Signal

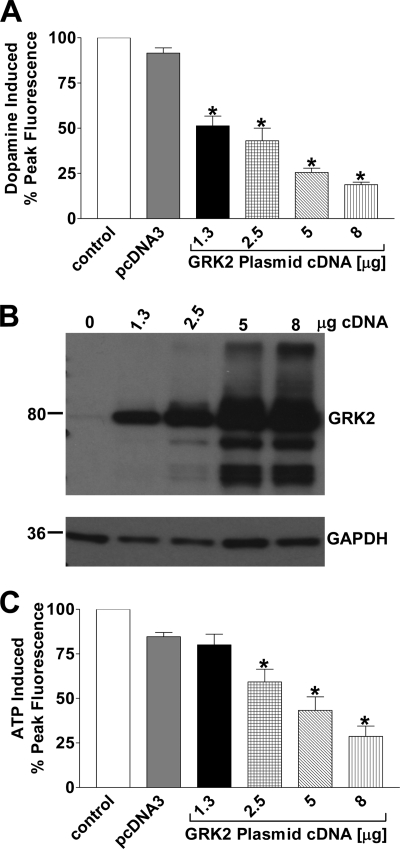

To analyze the mechanism by which GRK2 mediated the D1-D2 receptor heteromer calcium signal desensitization, GRK2 was transiently transfected into the D1-D2 receptor heteromer stable cell line in increasing concentrations, which led to a progressive attenuation of the calcium signal when activated with dopamine (Fig. 6, A, third through sixth bars and B). No significant decrease in this calcium signal was observed when cells were transfected with the empty vector pcDNA3. The addition of ATP to the GRK2-transfected cells to activate endogenously expressed purinergic receptors that couple to Gq also demonstrated a progressive decline in the ATP-mediated calcium signal, indicating the GRK2 was active in these cells (Fig. 6C, third through sixth bars).

FIGURE 6.

Increased expression of GRK2 led to a concentration-dependent decrease of the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-activated calcium signal. Data represent the percentage of peak fluorescence of the agonist-induced calcium signal, and values are the means ± S.E. of the numbers shown in brackets below. A, shown is activation of the D1-D2 receptor-mediated calcium signal with 10 μm dopamine in cells without or with increasing expression of GRK2 (n = 4). B, the immunoblot demonstrates the increasing expression of GRK2 in D1-D2 receptor expressing cells transfected with GRK2 cDNA. GAPDH immunoreactivity was used as a control for protein loading. C, activation of the endogenous purinergic receptor-mediated calcium signal with 10 μm ATP in cells without or with increasing expression of GRK2 (n = 3–4). A significant difference from control is denoted by * = p < 0.05.

The GRK 2 crystal structure confirms that it is composed of three functional domains: an amino-terminal RGS domain, a central protein kinase domain, and a carboxyl-terminal Gβγ pleckstrin homology domain (20). To determine whether the calcium signal attenuation was due to catalytic or RGS activity, GRK2 mutant constructs were transiently transfected into the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-expressing cells. Transfection of the catalytically inactive GRK2 (GRK2-K220R), previously shown as being capable of acting in a dominant negative manner to reverse desensitization of some GPCRs (21–23), led to a partial but not complete restoration of the calcium signal after transfection of 2.5 or 5 μg of cDNA, in comparison to wild type GRK2 (Fig. 7, A, third and fourth bars and the sixth and seventh bars, and B, third and sixth lanes). Because expression of the catalytically inactive GRK2 only led to a partial recovery of the calcium signal, the involvement of the RGS domain of GRK2 was investigated. Expression of a GRK2 mutant (GRK2-D110A), which lacks the ability to interact with Gq (24), also led to a partial but not complete restoration of the signal after transfection of 2.5 or 5 μg of cDNA in comparison to wild type GRK2 (Fig. 7, A, third and fifth bars and sixth and eight bars and B, fourth and seventh lanes). Co-expression of a GRK2 double point mutant (GRK2-R106A/K220R) that lacked both catalytic and RGS function led to full restoration of the calcium signal after transfection of 1 μg of cDNA and partial restoration after transfection of 2.5 and 5 μg of cDNA (Fig. 7, C, three through fifth bars, and D). Taken together, these results indicated that both the RGS and catalytic domains of GRK2 played a role in inhibiting D1-D2 receptor heteromer signaling after activation.

FIGURE 7.

Effect of catalytic domain mutated or RGS domain-mutated GRK2 on the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-mediated calcium signal. Data represent the percentage of peak fluorescence of the dopamine-induced calcium signal, and values are the means ± S.E. of the numbers shown in brackets below. A, shown is activation of the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-mediated calcium signal by 10 μm dopamine in cells without or with expression of 2.5 or 5 μg of cDNA for GRK2 (third and sixth bars), GRK2-K220R (fourth and seventh bars), or GRK2 D110A (fourth and eight bars) (n = 3–5). B, shown is an immunoblot demonstrating the increasing expression of GRK2 and mutated constructs in D1-D2 receptor-expressing cells. GAPDH immunoreactivity was used as a control for protein loading. C, shown is activation of the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-mediated calcium signal with 10 μm dopamine in cells without or with increasing expression of GRK2-R106A/K220R (n = 3). D, shown is an immunoblot demonstrating the increasing expression of GRK2-R106A/K220R. GAPDH immunoreactivity was used as a control for protein loading. A significant difference from control is denoted by * = p < 0.05.

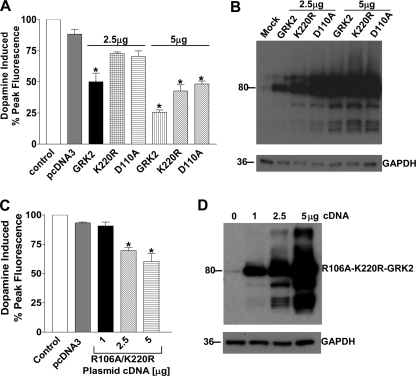

The involvement of GRK2 and its mutant constructs in the desensitization of the dopamine induced calcium signal after agonist pretreatment was also investigated. Increased expression of GRK2 led to a significant increase in desensitization of the dopamine induced signal after pretreatment with either SKF 83959 or SKF 83822 for 30 min (Fig. 8A). Expression of either GRK2-K220R or GRK2-D110A did not lead to any significant changes in the level of desensitization after pretreatment with either agonist (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

Effect of GRK2, catalytic domain-mutated or RGS domain-mutated GRK2 on the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-mediated calcium signal after agonist pretreatment with dopamine agonists for 30 min. Data represent the percentage of peak fluorescence of the dopamine-induced calcium signal, and values are the means ± S.E. of the numbers shown in brackets below. A, shown is activation of the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-mediated calcium signal by 10 μm dopamine in cells after pretreatment with 1 μm SKF 83959 or SKF 83822 without or with expression of 1.3 μg cDNA for GRK2 (n = 3–4). B, shown is activation of the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-mediated calcium signal by 10 μm dopamine in cells after pretreatment with 1 μm SKF 83959 or SKF 83822 without or with expression of 1.3 μg of cDNA for GRK2-K220R or GRK2 D110A (n = 3–5). A significant difference from control is denoted by * = p < 0.05.

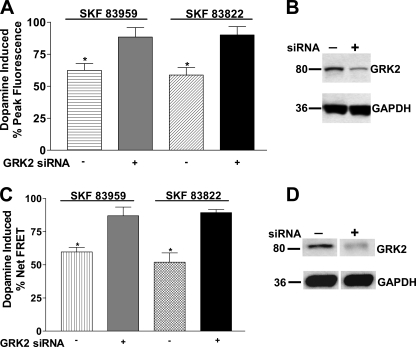

To further validate the role of GRK2 in desensitization of the calcium signal, endogenous GRK2 was silenced with siRNA in both the D1-D2 receptor heteromer stable cell line as well as in striatal neurons. Transfection of siRNA to silence GRK2 in the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-expressing cells resulted in significant recovery of the calcium signal after pretreatment with either SKF 83959 or SKF 83822 for 30 min (Fig. 9A). Furthermore, the knockdown of endogenous GRK2 led to a significantly higher dopamine-induced calcium signal in the absence of agonist pretreatment in two of the three experiments performed, indicating the contribution of physiological levels of endogenous GRK2 in regulating the peak height of the dopamine-induced calcium signal (data not shown). The siRNA-mediated reduction in expression of GRK2 levels was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 9B). Knockdown of endogenous GRK2 in the striatal neurons also resulted in significant recovery of the dopamine-induced calcium signal after exposure to either SKF 83959 or SKF 83822 for 30 min (Fig. 9C). The siRNA-mediated reduction in expression of GRK2 levels in the striatal neurons was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 9D).

FIGURE 9.

Decreased expression of GRK2 by siRNA led to significant recovery of the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-mediated calcium signal after pretreatment with either SKF 83959 or SKF 83822 in D1-D2 receptor heteromer-expressing cells and striatal neurons. Data represent the percentage of peak fluorescence (A) or peak FRET levels (C) of the dopamine-induced calcium signal, and values are the means ± S.E. of the numbers shown in brackets below. A, shown is desensitization of the calcium signal elicited by dopamine after pretreatment with 1 μm SKF 83959 or 1 μm SKF 83822 for 30 min in the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-expressing cells after expression of either non silencing (−) or GRK2 siRNA (+) (n = 3). B, shown is an immunoblot demonstrating the decreased expression of GRK2 in D1-D2 receptor heteromer-expressing cells. GAPDH immunoreactivity was used as a control for protein loading. C, shown is desensitization of the calcium signal elicited by dopamine after pretreatment with 100 nm SKF 83959 or 100 nm SKF 83822 for 30 min in striatal neurons after expression of either non silencing (−) or GRK2 siRNA (+). Peak FRET levels were measured from a range of 35–60 neurons from a total of 3 experiments. D, shown is an immunoblot demonstrating the decreased expression of GRK2 in striatal neurons. GAPDH immunoreactivity was used as a control for protein loading. A significant difference from control (no pretreatment) is denoted by * = p < 0.05.

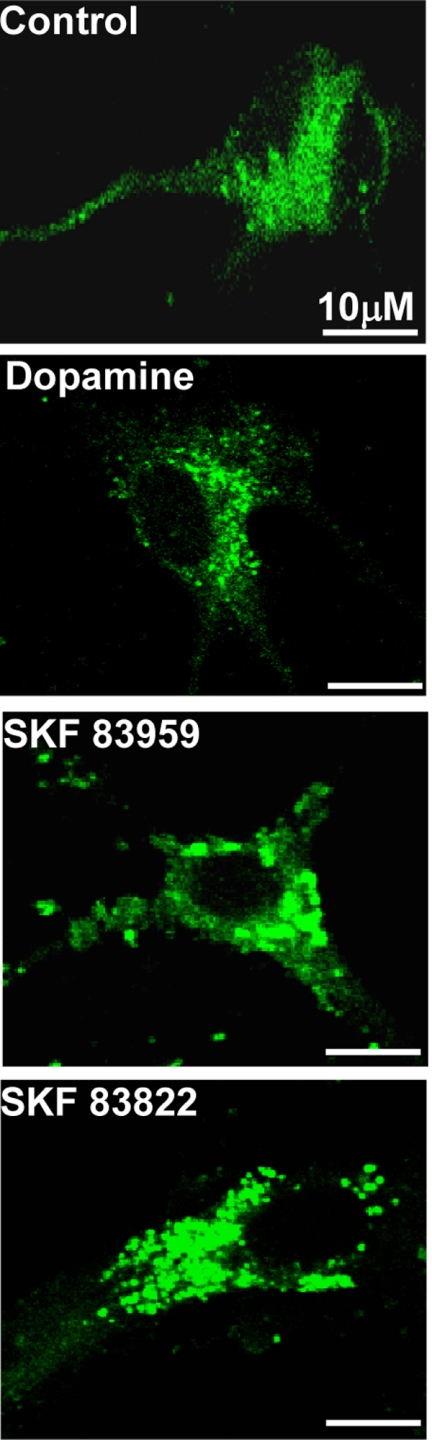

To examine whether the agonists induced recruitment of GRK2 to the D1-D2 receptor heteromer, we performed immunocytochemistry on striatal neurons. Pretreatment of the striatal neurons with 100 nm dopamine, SKF 83959, or SKF 83822 for 5 min each led to relocalization of GRK2 in a punctuate distribution to a similar extent, indicating GRK2 reactivity induced by these agonists (Fig 10).

FIGURE 10.

Immunocytochemistry of striatal neurons in culture showing endogenously expressed GRK2 localization before (Control) and after exposure to either 100 nm dopamine, SKF 83959, or SKF 83822 for 5 min.

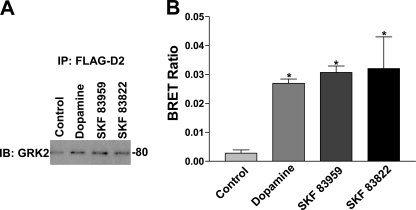

To determine whether GRK2 physically interacted with the D1-D2 receptor heteromeric complex, we performed co-immunoprecipitation studies. After 5 min of agonist treatment of HEK cells stably expressing both the HA-D1 and FLAG- D2 receptors, the FLAG-D2 receptor was immunoprecipitated from a P2 membrane preparation. Immunoblotting of this preparation revealed a band corresponding to the HA-D1 receptor for control and all agonist treatments (data not shown). Immunoblotting of this precipitate also revealed a band corresponding to GRK2 at 80 kDa for each agonist treatment that was higher than the control band (no agonist treatment) (Fig 11A), indicating an agonist-induced increase in the physical association between the D1-D2 receptor heteromeric complex and GRK2. To measure the extent of GRK2 recruitment to the D1-D2 receptor hetero-oligomer, the GRK2 immunoblot was normalized to the amount of FLAG-D2 receptor immunoprecipitated for vehicle and each agonist treatment. There was a 350, 270, and 168% increase in GRK2 precipitation with the FLAG-D2 receptor compared with control for dopamine, SKF 83959, and SKF 83822, respectively.

FIGURE 11.

A, co-immunoprecipitation of GRK2 with FLAG-D2 receptor from P2 membranes expressing FLAG-D2 receptor, HA-D1 receptor, and GRK2 after the cells were treated with vehicle (Control), 1 μm dopamine, SKF 83959, or SKF 83822 for 5 min. IP, immunoprecipitation with FLAG antibody; IB, immunoblot with GRK2 antibody. B, shown is BRET detection of Rluc-D1 and GFP-GRK2 interaction after 1 min of treatment with vehicle (Control) or 1 μm dopamine, SKF 83959, or SKF 83822. Values shown are the means ± S.E. of n = 3 experiments. A significant difference from control is denoted by * = p < 0.05.

Furthermore, to confirm a direct agonist-induced interaction between the D1-D2 receptor heteromer and GRK2, a BRET assay was performed with HEK 293 cells transfected with Rluc-D1 receptor, D2 receptor, and GFP-GRK2 or GFP cDNAs. Treatment with 1 μm dopamine, SKF 83822, or SKF 83959 for 1 min led to a rapid rise in the BRET ratio in comparison to control (no agonist treatment) (Fig. 11B) and declined within 10 min of agonist exposure (data not shown). This indicated a rapid agonist-induced association (proximity <100 Å) between Rluc-D1 receptor and GFP-GRK2. No significant agonist-induced BRET signal in comparison to control was observed between D1-Rluc and GFP (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated the desensitization of the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-mediated calcium signal by agonists with varying efficacies to activate the calcium signal. Although both SKF 81297 and SKF 83959 were shown to robustly activate the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-mediated signal, SKF 83822 did not significantly activate it in either the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-expressing cells or striatal neurons. However, all three agonists were able to significantly desensitize the signal within 5 min, and the desensitization elicited by SKF 83822 was not significantly different when either AC or PKA was inhibited. This suggested that D1-D2 receptor heteromer activation was not a prerequisite for desensitization of its signal, and occupancy of the receptor binding pocket with its associated conformational changes could result in desensitization. Desensitization of the calcium signal occurred independently of calcium storage capacity and exogenous calcium entry, indicating no impairment of calcium kinetics, thus suggesting that desensitization occurred at the receptor level. Increased expression of GRK2 led to a concentration-dependent decrease of the calcium signal, and knockdown of GRK2 by siRNA led to an increase in the calcium signal. The GRK2 catalytically inactive or RGS-mutated constructs each led to a partial reversal of the GRK2 calcium signal effect, suggesting that both GRK2 domains were involved, and thus, GRK2 had a dual role in mediating calcium signal desensitization. This is the first demonstration of GRK2 having a bifunctional role in regulating a GPCR hetero-oligomer where the constituent receptor homo-oligomers are not coupled to the Gq protein.

All three agonists with high affinities for the D1 receptor were compared for their ability to stimulate intracellular calcium release through the D1-D2 receptor hetero-oligomer. Although SKF 83959 and SKF 81297 generated robust calcium signals, SKF 83822 was unable to generate a significant calcium signal in either the D1-D2 receptor heteromer expressing cells or in striatal neurons. We have previously demonstrated that the D1-D2 receptor heteromer is coupled to Gq, which could be activated by SKF 83959 but not by SKF 83822, as shown by [35S]GTPγS incorporation into Gq (13). Desensitization of the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-mediated calcium signal occurred not only by exposure to SKF 83959 and SKF 81297 but also by SKF 83822 to a level comparable with the other agonists. This suggested that D1-D2 receptor heteromer activation was not a prerequisite for its desensitization and that a ligand occupying the binding pocket of one constituent receptor with high affinity could result in desensitization. A heterologous mechanism involving the AC pathway was not responsible for this observed desensitization as inhibition of AC or PKA did not significantly change the attenuation of the signal by SKF 83822 in striatal neurons. These results suggested that receptor occupancy by the agonist and its associated conformational changes may be sufficient for desensitization of the signal without G protein activation. Biochemical and biophysical data suggest that different ligands can indeed induce and/or stabilize subsets of the multiple active conformations of a receptor (25, 26). It is possible that occupancy of the receptor by SKF 83822 leads to a stabilization of the receptor into a conformation where it becomes a target for kinases, β-arrestins, or endocytic machinery without G protein activation. In fact, several ligands that recruit β-arrestin and/or induce receptor internalization without stimulating G protein signaling have been identified. Receptors for which this has been shown include the angiotensin II type 1 receptor (27), β2-adrenoreceptor (28), chemokine CCR7 (29), and CXCR4 (30) receptors and type 1 parathyroid hormone receptor (31). However, as opposed to these homo-oligomeric complexes, agonist-induced structural changes within the D1-D2 receptor hetero-oligomer likely exhibits an increased level of complexity as a result of the presence of two distinct dopamine receptor subtypes within a single heteromeric complex and, hence, an increased potential for multiple conformational states.

We utilized GRK2 mutated constructs to explore the importance of distinct functional domains within GRK2 in mediating D1-D2 receptor heteromer desensitization. Increasing the expression level of GRK2 led to a decrease in the calcium signal, and decreasing the expression level led to an increase in the calcium signal. The catalytically inactive and RGS-mutated GRK2 constructs each led to a partial recovery of the GRK2-mediated signal attenuation, indicating the involvement of both domains.

The lowest concentration of GRK2-R106A/K220R, which lacked both the catalytic and RGS functions, led to a complete recovery of the calcium signal, providing further evidence that both GRK2 domains were involved in the calcium signal regulation. However, expression of GRK2-R106A/K220R at higher concentrations was not able to completely restore the calcium signal. Although GRK2-R106A/K220R contains a mutation within its RGS domain resulting in prevention of Gq binding, it is possible that it still retains the ability to bind the D1-D2 receptor heteromeric complex. Indeed, a recent study has demonstrated that GRK2 and several of its mutants including the catalytically inactive and RGS-mutated GRK2 constructs were able to co-immunoprecipitate with the D2 receptor homo-oligomer (32). A similar phenomenon has been demonstrated for the metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 (mGluR1), where GRK2 mutants impaired in Gq binding could still bind avidly to the mGluR1 receptor (33). Thus, we postulated that the failure of higher concentrations of GRK2-R106A/K220R to completely restore calcium signaling could be attributed to steric hindrance of receptor-Gq coupling caused by GRK2-R106A/K220R binding to the D1-D2 receptor heteromeric complex. Our results are consistent with what has been reported for the Gq-coupled H1 histamine receptor (H1HR), where although lower concentrations of the GRK2 double mutant resulted in little inhibition of agonist-induced inositol phosphate production, higher concentrations showed a partial inhibitory effect (34). Thus, it is possible that a similar process occurred in the present system where excessive binding of GRK2-R106A/K220R to the D1-D2 receptor heteromer resulted in the attenuation of inherent receptor Gq interactions.

The involvement of GRK2 in calcium signal desensitization after agonist pretreatment with either SKF 83959 or SKF 83822 was confirmed by both increasing and decreasing the expression of GRK2 in D1-D2 receptor heteromer-expressing cells as well as by significant knockdown of endogenous GRK2 in primary culture neurons. Because SKF 83822 does not activate the calcium signal but has structural similarity to SKF 83959, these results suggest that GRK2 may be involved in receptor occupancy-mediated calcium desensitization by either SKF 83822 or SKF 83959. Accordingly, agonist-induced recruitment of GRK2 to the D1-D2 receptor heteromer was shown by the redistribution of GRK2 to the cell periphery as well as significant co-immunoprecipitation of both GRK2 and the D1 receptor with the D2 receptor after agonist treatment. Although the co-immunoprecipitation data indicated that SKF 83822 resulted in less GRK2 recruitment than dopamine or SKF 83959, all three agonists still elicited equivalent levels of desensitization of the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-mediated calcium signal. Furthermore, there was a significant BRET signal between the D1 receptor and GRK2 in the presence of the D2 receptor, indicating a physical association between the two proteins that was enhanced by all three agonists.

Expression of either GRK2-K220R or GRK2-D110A did not attenuate the desensitization of the calcium signal elicited by exposure to either agonist. This is in contrast to what was observed in the absence of agonist pretreatment where expression of either construct each led to a partial reversal of the GRK2 attenuated calcium signal. It is possible that the presence of agonist resulted in a greater recruitment of endogenous GRK2 to the D1-D2 receptor heteromeric complex in comparison to the basal state, resulting in increased signal attenuation and, therefore, may have masked any calcium signal recovery effects by the GRK2 mutant constructs. Agonist-induced recruitment of GRK2 to the D1-D2 receptor heteromer was shown by immunocytochemistry, co-immunoprecipitation, and BRET assays.

Alternatively, other GRK2-independent mechanisms may also be involved in the calcium signal attenuation. For example, agonist exposure may induce the formation of a stable receptor conformation that prevents restoration of the calcium signal, or the receptor complex may have internalized or have been disrupted after agonist pretreatment and, thus, may have resulted in a decreased dopamine-induced calcium signal even in the presence of the GRK2 mutant constructs.

Although GRK2-mediated desensitization has been reported for both D1 and D2 receptor homo-oligomers, only the catalytic activity of GRK2 has been indicated to be important for the D1 receptor (35–37). For D2 receptor regulation, a recent study has provided evidence to suggest a role for the GRK2 carboxyl-terminal, Gβγ pleckstrin homology domain in addition to catalytic function (32). Given this evidence, it is possible that the GRK2 Gβγ pleckstrin homology domain may also be involved in D1-D2 receptor heteromer regulation, and this will be important to investigate. Interestingly, the GRK2 RGS domain was not involved in suppressing D2 receptor homo-oligomer signaling (32). Thus, our results indicated that D1-D2 receptor hetero-oligomer signaling regulation by GRK2 was distinct from D1 and D2 receptor homo-oligomer regulation, where this dual function involving both the catalytic and RGS domains of GRK2 in inhibiting signaling has not been reported. Additionally, AC activity regulated by D1 and D2 receptor homo-oligomers is maximal within 15–30 min (38, 39), whereas the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-mediated calcium signal peaks within seconds of activation. Thus, it is possible that the rapid nature of this calcium signal requires a quick and robust quenching mechanism that cannot be controlled by the GRK2 catalytic activity alone, and therefore, regulation by both the catalytic and RGS domains within GRK2 may favor the prompt termination of the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-mediated signal.

Signaling through the D1-D2 receptor heteromeric complex involves activation of the Gq/calcium pathway. We cannot determine whether the D1-D2 receptor heteromer is also able to signal through the Gs/cAMP pathway, but we have previously demonstrated that the agonist SKF 83959, which selectively activates the D1-D2 receptor heteromer, did not activate Gs/olf in striatal membranes but activated Gq as shown by incorporation of [35S]GTPγS (13).

Another potential mechanism for decreased calcium signaling after agonist exposure is that agonist occupancy of the receptors triggers the D1-D2 receptor complex to break apart, thus disrupting and turning off the signal. Although a majority of studies indicates that cell surface homo-oligomers remain intact after agonist activation (10, 40, 41), agonist-dependent dissociation of GPCR oligomers has been suggested to occur for certain receptors (42, 43).

In summary, we demonstrated that desensitization of the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-mediated calcium signal occurs by D1 receptor occupancy with or without signal activation and that GRK2 plays a role in regulating the signal response both at the basal level as well as after agonist pretreatment. Our results provide evidence for an entirely novel aspect of dopamine D1-D2 receptor heteromer desensitization that is distinct from mechanisms that have been reported for D1 or D2 receptor homo-oligomers. The data suggested that the D1-D2 receptor hetero-oligomer can achieve functionally distinct active conformations as a result of differential ligand occupancy by demonstrating the intriguing ability for D1 receptor agonist occupancy within the D1-D2 receptor complex to elicit calcium signal desensitization without activation. Additionally, the contribution of both catalytic and Gq binding functions of GRK2 to regulate D1-D2 receptor hetero-oligomer signaling not only implicated the significance of different domains within GRK2 but also demonstrated the potential for unique D1-D2 receptor hetero-oligomer regulation. Determining precisely how D1-D2 receptor heteromer intracellular signaling is regulated will not only increase our understanding of the available repertoire of dopamine receptor signaling pathways but also enable investigation of how these signaling pathways may be disrupted in pathogenic states such as schizophrenia and Parkinson disease. Therefore, elucidation of the regulation of the D1-D2 receptor heteromer-mediated calcium signal may expand our understanding of the development of tolerance and neuronal adaptation in diseases for which the D1-D2 receptor heteromer plays a role.

Acknowledgments

We thank Theresa Fan and Dr. Melissa Perreault for technical assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant DA007223 (from the National Institute on Drug Abuse).

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- AC

- adenylyl cyclase

- GRK

- G protein-coupled receptor kinase

- RGS

- regulator of G protein signaling

- HBSS

- Hank's balanced salt solution

- SKF 83822

- 6-chloro-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1-(3-methylphenyl)-3-(2-propenyl)-1H-3-benzazepine-7,8-diol hydrobromide

- SKF 83959

- 6-chloro-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-3-methyl-1-(3-methylphenyl)-1H-3-benzazepine-7,8-diol

- SKF 81297

- 6-chloro-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1-phenyl-1H-3-benzazepine hydrobromide

- BRET

- bioluminescence resonance energy transfer

- GTPγS

- guanosine 5′-O-(thiotriphosphate)

- YFP and CFP

- yellow and cyan fluorescent proteins, respectively.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pivonello R., Ferone D., Lombardi G., Colao A., Lamberts S. W., Hofland L. J. (2007) Eur. J. Endocrinol. 156, S13–S21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerfen C. R., Keefe K. A., Gauda E. B. (1995) J. Neurosci. 15, 8167–8176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kita K., Shiratani T., Takenouchi K., Fukuzako H., Takigawa M. (1999) Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 9, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Svenningsson P., Fredholm B. B., Bloch B., Le Moine C. (2000) Neuroscience 98, 749–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aizman O., Brismar H., Uhlén P., Zettergren E., Levey A. I., Forssberg H., Greengard P., Aperia A. (2000) Nat. Neurosci. 3, 226–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertran-Gonzalez J., Bosch C., Maroteaux M., Matamales M., Hervé D., Valjent E., Girault J. A. (2008) J. Neurosci. 28, 5671–5685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee K. W., Kim Y., Kim A. M., Helmin K., Nairn A. C., Greengard P. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 3399–3404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee S. P., So C. H., Rashid A. J., Varghese G., Cheng R., Lança A. J., O'Dowd B. F., George S. R. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 35671–35678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.George S. R., Lee S. P., Varghese G., Zeman P. R., Seeman P., Ng G. Y., O'Dowd B. F. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 30244–30248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee S. P., O'Dowd B. F., Ng G. Y., Varghese G., Akil H., Mansour A., Nguyen T., George S. R. (2000) Mol. Pharmacol. 58, 120–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Dowd B. F., Ji X., Alijaniaram M., Rajaram R. D., Kong M. M., Rashid A., Nguyen T., George S. R. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 37225–37235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.So C. H., Varghese G., Curley K. J., Kong M. M., Alijaniaram M., Ji X., Nguyen T., O'Dowd B. F., George S. R. (2005) Mol. Pharmacol. 68, 568–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rashid A. J., So C. H., Kong M. M., Furtak T., El-Ghundi M., Cheng R., O'Dowd B. F., George S. R. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 654–659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasbi A., Fan T., Alijaniaram M., Nguyen T., Perreault M. L., O'Dowd B. F., George S. R. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 21377–21382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.So C. H., Verma V., O'Dowd B. F., George S. R. (2007) Mol. Pharmacol. 72, 450–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y., Elangovan M., Periasamy A. (2005) Molecular Imaging: FRET Microscopy and Spectroscopy, Oxford University Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 17.Truong K., Sawano A., Mizuno H., Hama H., Tong K. I., Mal T. K., Miyawaki A., Ikura M. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 1069–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angers S., Salahpour A., Joly E., Hilairet S., Chelsky D., Dennis M., Bouvier M. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 3684–3689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schachter J. B., Li Q., Boyer J. L., Nicholas R. A., Harden T. K. (1996) Br. J. Pharmacol. 118, 167–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lodowski D. T., Pitcher J. A., Capel W. D., Lefkowitz R. J., Tesmer J. J. (2003) Science 300, 1256–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Claing A., Laporte S. A., Caron M. G., Lefkowitz R. J. (2002) Prog. Neurobiol. 66, 61–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferguson S. S. (2001) Pharmacol. Rev 53, 1–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krupnick J. G., Benovic J. L. (1998) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 38, 289–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sterne-Marr R., Tesmer J. J., Day P. W., Stracquatanio R. P., Cilente J. A., O'Connor K. E., Pronin A. N., Benovic J. L., Wedegaertner P. B. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 6050–6058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swaminath G., Deupi X., Lee T. W., Zhu W., Thian F. S., Kobilka T. S., Kobilka B. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 22165–22171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vilardaga J. P., Steinmeyer R., Harms G. S., Lohse M. J. (2005) Nat. Chem. Biol. 1, 25–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei H., Ahn S., Shenoy S. K., Karnik S. S., Hunyady L., Luttrell L. M., Lefkowitz R. J. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 10782–10787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swaminath G., Xiang Y., Lee T. W., Steenhuis J., Parnot C., Kobilka B. K. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 686–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohout T. A., Nicholas S. L., Perry S. J., Reinhart G., Junger S., Struthers R. S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 23214–23222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sachpatzidis A., Benton B. K., Manfredi J. P., Wang H., Hamilton A., Dohlman H. G., Lolis E. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 896–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gesty-Palmer D., Chen M., Reiter E., Ahn S., Nelson C. D., Wang S., Eckhardt A. E., Cowan C. L., Spurney R. F., Luttrell L. M., Lefkowitz R. J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 10856–10864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Namkung Y., Dipace C., Urizar E., Javitch J. A., Sibley D. R. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 34103–34115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dhami G. K., Dale L. B., Anborgh P. H., O'Connor-Halligan K. E., Sterne-Marr R., Ferguson S. S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 16614–16620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iwata K., Luo J., Penn R. B., Benovic J. L. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 2197–2204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jackson A., Iwasiow R. M., Chaar Z. Y., Nantel M. F., Tiberi M. (2002) J. Neurochem. 82, 683–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim O. J., Gardner B. R., Williams D. B., Marinec P. S., Cabrera D. M., Peters J. D., Mak C. C., Kim K. M., Sibley D. R. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 7999–8010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamey M., Thompson M., Varghese G., Chi H., Sawzdargo M., George S. R., O'Dowd B. F. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 9415–9421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryman-Rasmussen J. P., Nichols D. E., Mailman R. B. (2005) Mol. Pharmacol. 68, 1039–1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tong J., Ross B. M., Sherwin A. L., Kish S. J. (2001) Neurochem. Int. 39, 117–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Babcock G. J., Farzan M., Sodroski J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 3378–3385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dinger M. C., Bader J. E., Kobor A. D., Kretzschmar A. K., Beck-Sickinger A. G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 10562–10571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng Z. J., Miller L. J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 48040–48047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ginés S., Hillion J., Torvinen M., Le Crom S., Casadó V., Canela E. I., Rondin S., Lew J. Y., Watson S., Zoli M., Agnati L. F., Verniera P., Lluis C., Ferré S., Fuxe K., Franco R. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 8606–8611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Violin J. D., Ren X. R., Leftkowitz R. J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 20577–20588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]