Introduction

In 2008, the American Cancer Society estimates that approximately 11,070 new cases of invasive cervical cancer were diagnosed with 3,870 subsequent cervical cancer deaths.1 South Carolina (SC) has some of the largest health disparities in the nation, predictor of in particular cancer mortality rates that disfavor African Americans (AA) in comparison to European Americans (EA).2 Using electronic data sources, the age-adjusted incidence rate of cervical cancer in SC from 1996 to 2005 was 37% higher for AA women compared to EA women (8.9/100,000 for EA, and 14.1/100,000 for AA).3 These same electronic data sources indicate that age-adjusted mortality is 61% higher in AA than EA women (2.4/100,000 for EA, and 6.2/100,000 for AA).3 Cervical cancer is one of the few cancers for which screening represents a primary prevention tool (i.e. lesions can be detected in precursor stages), thus the majority of all cases and ultimately deaths may be prevented by appropriate screening. AA women living in rural SC are among the least likely population to have received recommended screenings.4

Mortality disparities in cervical cancer have been partially explained by the lack of early detection due to non-adherence to screening protocols, but the racial disparity gap between EA and AA cannot be explained entirely by differences in screening rates.4 An analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program data from 1988 to 1994, found 43.8% of AA women and 34.8% of EA women were diagnosed with advanced disease.5 With adjustment made for other factors, race was still found to be a significant cervical cancer.5 AA were also found to be at a 19% increased risk of death compared to EA over a five-year follow-up period after adjusting for several factors such as age at diagnosis, histology, stage, and first course of cancer-directed therapy.6 The independent effects of race and socioeconomic status have been intensely studied in the cervical cancer mortality literature.7–19 While many have concluded that race has an effect on cervical cancer survival independent of socioeconomic status10, 12, 18–19, others have found that all disparities were explained by socioeconomic status alone.7–8, 13, 17 Howell and colleagues concluded that more work was needed to determine the basis of the racial disparity.5

Interestingly, further research analyzing SEER data using census tracts to establish “Working Poor” and “Professional” regions found that race was not as strong of a predictor as was access to care.20 Another similar study found that stage of disease and treatment type were more influential than race and socioeconomic status on mortality.5, 21 With this mounting evidence on the possible sources of the mortality disparity between EA and AA populations, other factors such as comorbidity, severity of disease at diagnosis, and socioeconomic status should be considered both individually and in combination with each other.5

The lack of consensus on the causes of disparities in cervical cancer mortality highlights the need to better understand differences in clinical disease between EA and AA. In addition, very few studies have attempted to describe the disparities among rural AA and EA women. As SC is a predominately rural state with AA representation of over 30%22, it offers the ideal population in which to further expand our knowledge of cervical cancer disparities. Fortunately, as a cancer for which screening represents a primary prevention tool, interventions within those populations at risk have the immediate potential to significantly impact these racial disparities. In order to fully understand the extent of these disparities, the purpose of this investigation was to determine whether AA women with cervical cancer were more likely to die than EA women with cervical cancer.

Methods

All data utilized for this analysis were collected as part of the SC Central Cancer Registry.23 The state registry maintains a “gold certification” rating through the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAAC-CR). Consequently, the data are of high quality, validity, and completeness. Due to the fact that all data for this analysis had been previously collected for reporting purposes and were de-identified, the investigation was exempt from Institutional Review Board review.

Study Population

The study population consisted of all women diagnosed with a histopathologically confirmed, first primary cervical neoplasm within SC between January 1, 1996 and December 31, 2006. The registry used ICD-O-2 and ICD-O-3 codes24–25 depending on the year of diagnosis (C53.0-C53.9) in combination with histology to exclude any non-cervical neoplasms. Women were excluded if they had a previous cancer diagnosis or were under 20data years of age. They also were excluded if the cervical cancer diagnosis was documented only upon autopsy or the death certificate. It should be noted that specific cause of death is a restricted data element for the SCCCR and was not available for analysis. Only those women with a race designation of either “Black” or “White” (designations used by the registry) were used for this investigation. As the registry categorizes all other ethnicities into an “other” category, we were unable to extend this analyses beyond these racial groups. A total of 2,027 women were identified who met the inclusion criteria.

Variables

Histology, defined by ICD-O-324, was collapsed into 5 groups using the first 3 digits of the classification, general neoplasm (800), general carcinoma (801), squamous cell carcinoma (807), adeno-carcinoma (814, 838, or 856), and all others. Marital status was categorized as single; separated, including divorced, or widowed; married; or unknown. Information on cancer treatment was not routinely collected by the registry until 2006 and was missing for more than 75% of cases in this cohort. Additional variables under study included alcohol use (never, current, past, or unknown), age at diagnosis, grade (well differentiated, moderately differentiated, poorly differentiated, undifferentiated, and unknown), stage (local, regional, distant, un-staged), cause of death (cancer, other, unknown), year of diagnosis, and year of death.

Statistical Analysis

An alpha level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance for all tests. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (Cary, NC). Descriptive statistics were calculated and compared by race using either a Chi-square test or t-test, as appropriate. The data are comprised of a linkage (using both SAS and Link Plus software) between 1996–2005 SC cervical cancer incidence data linked to1996–2006 SC death certificate and 1996–2006 National Death Index (NDI) data26 and 1996–2006 Social Security Death Index (SSDI) data27 using a combination of both deterministic and probabilistic matching. All SCCCR data not matched through the vital records linkage are prepared and sent to NCHS for linkage to the NDI. Results provided are run through a National Program of Cancer Registries approved algorithm to determine true, probable, and non-matches. True matches are accepted, probable matches are manually reviewed, and non-matches are considered to be alive (total match rate=48.1%). After linkage, cases not found to be deceased as of December 31, 2006, were considered to be alive at the time of censoring. Survival time for each woman was calculated as the number of days between the date of diagnosis and either the date of last follow-up (December 31, 2006; for all those categorized as “alive”) or date of death (for those categorized as “deceased”), or date of secondary malignancy. For those with a secondary malignancy, they were classified as “alive” for survival analyses and censored at the date of diagnosis for the second malignancy. Kaplan Meier survival curves were calculated and the log rank test statistic was used to assess for statistical differences between racial groups. In order to evaluate racial differences by tumor type, curves were calculated within specific sub-groups using the WHERE function.

Results

The characteristics of the population are shown in Table 1. Significant differences between races were noted for alcohol use, grade, histology, marital status, and vital status. Of note, over 30% of the data for alcohol use was unknown (missing). The proportion of deceased women was significantly higher among AA women compared to EA women (44% vs 29%, p < 0.01). For both racial groups, squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma were the most common histologies noted at diagnosis; however, a larger proportion of AA women were diagnosed with squamous cell cancers. For both grade and stage, AA women were significantly more likely than EA women to be diagnosed with poorer-prognosis tumor types.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for African American and European American cervical cancer patients, 1996–2005.

| Variable | AA | EA | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| %(n) | %(n) | ||

| Demographics | |||

| Marital Status: | <0.01 | ||

| Single, Separated, Widowed, & Divorced | 61 (457) | 40 (484) | |

| Married | 27 (204) | 52 (604) | |

| Unknown | 11 (85) | 8 (104) | |

| Alcohol Use: | <0.01 | ||

| Never | 49 (367) | 46 (565) | |

| Current | 14 (107) | 17 (209) | |

| Past | 5 (37) | 2 (30) | |

| Unknown | 32 (235) | 35 (424) | |

| Tumor Characteristics | |||

| Grade: | <0.01 | ||

| Well | 6 (42) | 9 (113) | |

| Moderate | 25 (188) | 29 (356) | |

| Poor | 31 (233) | 23 (284) | |

| Undifferentiated | 3 (21) | 2 (28) | |

| Unknown | 35 (262) | 37 (447) | |

| Histology: | <0.01 | ||

| Neoplasm | 1 (10) | 2 (21) | |

| Carcinoma | 3 (25) | 3 (39) | |

| Squamous Cell Carcinoma | 80 (593) | 70 (862) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 10 (76) | 19 (232) | |

| All Others | 6 (42) | 6 (74) | |

| Stage: | <0.01 | ||

| Local | 52 (387) | 62 (762) | |

| Regional | 31 (235) | 25 (313) | |

| Distant | 10 (71) | 6 (73) | |

| Un-staged | 7 (53) | 7 (80) | |

| Vital Statistics | |||

| Status: | <0.01 | ||

| Alive | 56 (415) | 71 (877) | |

| Dead | 44 (331) | 29 (351) | |

| Cause of Death: | 0.95 | ||

| Cancer | 76 (252) | 75 (265) | |

| Other | 19 (62) | 19 (66) | |

| Unknown | 5 (17) | 6 (20) | |

| Year of Death: | 0.37 | ||

| 1996 | 3 (10) | 2 (8) | |

| 1997 | 7 (22) | 5 (18) | |

| 1998 | 10 (33) | 10 (34) | |

| 1999 | 10 (34) | 10 (36) | |

| 2000 | 12 (41) | 7 (25) | |

| 2001 | 9 (31) | 13 (44) | |

| 2002 | 9 (29) | 10 (35) | |

| 2003 | 10 (32) | 13 (47) | |

| 2004 | 11 (36) | 9 (33) | |

| 2005 | 11 (38) | 11 (38) | |

| 2006 | 8 (25) | 10 (33) | |

| Year of Diagnosis: | 0.94 | ||

| 1996 | 13 (98) | 12 (142) | |

| 1997 | 12 (87) | 11 (140) | |

| 1998 | 10 (76) | 11 (137) | |

| 1999 | 13 (88) | 11 (140) | |

| 2000 | 8 (62) | 10 (117) | |

| 2001 | 11 (79) | 10 (122) | |

| 2002 | 10 (76) | 11 (137) | |

| 2003 | 8 (63) | 8 (102) | |

| 2004 | 8 (63) | 8 (93) | |

| 2005 | 7 (54) | 8 (98) | |

EA – European American; AA- African American

From Chi-square test for homogeneity

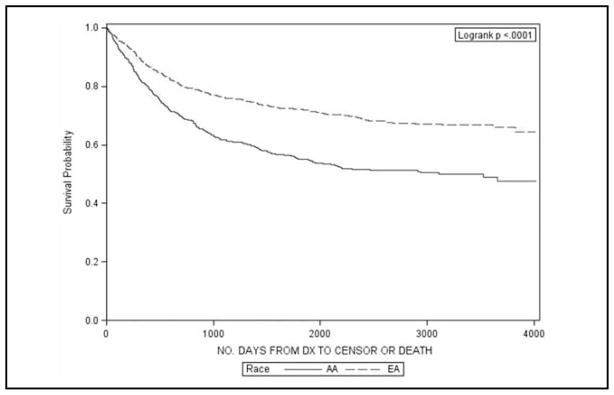

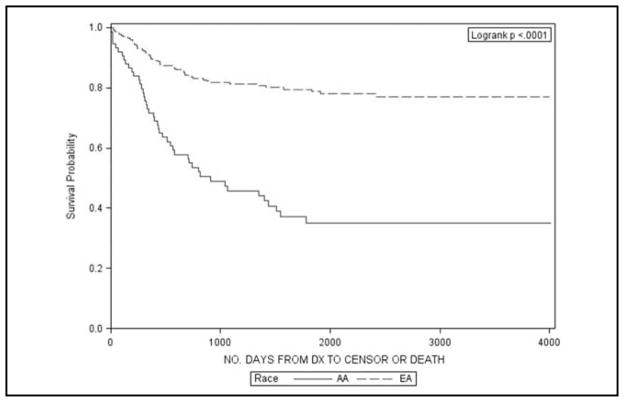

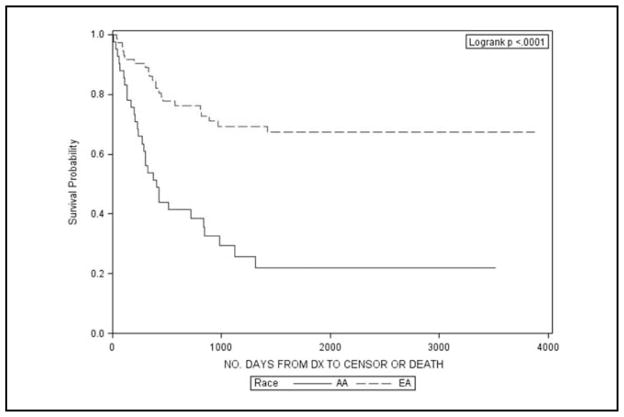

Table 2 describes the 3-, 5-, and 10-year survival proportions for AA and EA women by different cervical cancer sub-populations. Significant differences in survival were observed in the entire population with a 10-year survival proportion of 49% for AA and 66% for EA women (p < 0.01). This is also illustrated graphically in Figure 1. Upon stratification by stage, AA women with local or regional disease had significantly lower survival at 10 years than EA women (69% vs 81% and 30% vs 43%, respectively). Similarly, significantly lower survival was found for AA women for all histology types, except general carcinomas. The largest differences were noted for adenocarcinomas and other histologies (Figures 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Kaplan Meier survival results for African American and European American cervical cancer patients, 1996–2006.

| Population | Ethnicity | N | 3-Year Survival | 5-Year Survival | 10-Year Survival | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | AA | 746 | 62% | 55% | 49% | <0.01 |

| EA | 1228 | 76% | 72% | 66% | ||

| Stage: | ||||||

| Local Stage | AA | 387 | 81% | 75% | 69% | <0.01 |

| EA | 762 | 90% | 86% | 81% | ||

| Regional Stage | AA | 235 | 47% | 40% | 30% | <0.01 |

| EA | 313 | 59% | 52% | 43% | ||

| Distant Stage | AA | 71 | 11% | 10% | 10% | 0.63 |

| EA | 73 | 18% | 18% | 7% | ||

| Histology: | ||||||

| General Neoplasms | AA | 10 | 40% | 30% | 15% | <0.01 |

| EA | 21 | 75% | 70% | 57% | ||

| General Carcinomas | AA | 25 | 41% | 36% | 36% | 0.09 |

| EA | 39 | 71% | 65% | 44% | ||

| Squamous Cell Carcinoma | AA | 593 | 67% | 63% | 54% | <0.01 |

| EA | 862 | 76% | 71% | 65% | ||

| Adenocarcinomas | AA | 76 | 46% | 35% | 35% | <0.01 |

| EA | 232 | 81% | 79% | 77% | ||

| All Other Histology | AA | 42 | 29% | 22% | 22% | <0.01 |

| EA | 74 | 69% | 67% | 67% | ||

| Grade: | ||||||

| Well Differentiated | AA | 42 | 84% | 80% | 80% | 0.87 |

| EA | 113 | 85% | 83% | 80% | ||

| Moderately Differentiated | AA | 188 | 69% | 61% | 57% | 0.01 |

| EA | 356 | 79% | 74% | 66% | ||

| Poorly Differentiated | AA | 233 | 50% | 46% | 40% | 0.01 |

| EA | 284 | 64% | 60% | 57% | ||

| Undifferentiated | AA | 21 | 51% | 33% | 24% | 0.08 |

| EA | 28 | 68% | 63% | 52% | ||

| Marital Status: | ||||||

| Single | AA | 212 | 69% | 64% | 60% | 0.07 |

| EA | 167 | 79% | 74% | 70% | ||

| Married | AA | 204 | 67% | 58% | 54% | <0.01 |

| EA | 640 | 80% | 77% | 72% | ||

| Divorced, Widowed, Separated | AA | 245 | 51% | 45% | 37% | <0.01 |

| EA | 317 | 68% | 63% | 54% | ||

| Unknown | AA | 85 | 50% | 46% | 40% | <0.01 |

| EA | 104 | 64% | 59% | 57% | ||

EA – European American; AA- African American

From log rank test for Kaplan Meier survival curves

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier survival plots for African American (AA) and European American (EA) women with cervical cancer in South Carolina, 1996–2006.

Figure 2.

Kaplan Meier survival plots for African American (AA) and European American (EA) women with adenocarcinoma cervical cancer histology in South Carolina, 1996–2006.

Figure 3.

Kaplan Meier survival plots for African American (AA) and European American (EA) women with less common histology types of cervical cancer in South Carolina, 1996–2006.

In examining differences by grade, AA women diagnosed with moderately and poorly differentiated tumors experienced significantly lower survival at 10 years than EA women (57% versus 66% and 40% versus 57%, respectively). In order to examine how social support networks might influence survival, we examined survival by marital status (as a rough estimator). Significantly lower survival was found for AA women in the married and divorced/widowed/separated groups (all p-values < 0.01).

Discussion

With this investigation, we found significantly decreased survival among AA women with cervical cancer compared to EA women. The disparity persisted even among AA and EA women with the same disease stage, grade, or histology. These findings help to highlight the extent of the disproportionate burden of cervical cancer disease that AA women experience. This work also extends our understanding of the disparities among rural AA women who comprise much of this population.

The causes of these disparities are most likely multi-faceted and interdependent. On one end of the spectrum, these disparities may be partly attributable to natural variation in biological processes and functioning reflecting genetic and environmental factors and the interactions between them. On the other end of the spectrum, these disparities could be influenced by socioeconomic factors such as access to appropriate screening and post-diagnosis care. Still other possible factors influencing related to environmental and provider barriers to receiving appropriate cervical cancer screening and care.7–10, 12–19, 28–34

With our analysis of the impact of marital status on mortality, we attempted to account for possible social support. While marital status is an extremely crude measure of support, it is interesting that AA women in all four categories experienced significantly poorer survival. As would be expected, the highest survival proportions were noted in the married group, which is consistent with other studies showing a positive influence of social support on health outcome.35 Women may also receive other forms of support (family, friends, or church) which we were not able to account for by using marital status. While these findings certainly point out a need for further research, they also suggest areas for possible intervention. Marital status may be an indicator of emotional or psychological support, financial support, or support in “care-taking” responsibilities. Programs aimed at providing this type of support could have a significant impact on cervical cancer survival.

An important milestone in the history of cervical cancer is the development of a human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. As the majority of cervical cancer cases are preceded by HPV infection, administration of the vaccine has tremendous potential to prevent the development of cervical cancer.33 As the numbers of individuals who choose to be vaccinated increase, it will be important to understand the effect of vaccine use on cervical cancer survival.

The Cancer Plan for SC is a document which seeks to formulate and organize a cohesive strategy for addressing cancer prevention and control in SC.36 The plan specifically highlights possible strategies to eliminate health disparities in cancer. Consequently, this investigation addresses several key areas of the plan such as increasing awareness of racial disparities, aid in the dissemination of information about disparities, and educate key legislative officials about disparities. We see this work as an important first step which highlights the need for additional research to further understand the disparities and develop or disseminate interventions aimed at addressing the determinants of the disparities.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings from this study. While the SC Central Cancer Registry contains a wealth of data, information on the treatment course was not available for analysis. Given that post-diagnosis care is an important factor for survival, we were not able to evaluate disparities in cervical cancer treatment. It should also be noted that marital status information, while collected by the SCCCR, is not a required data element and is not quality controlled. Additionally, due to a large proportion of missing data, we were not able to account for the potential effect of socioeconomic indicators such as insurance type or education. On a similar note, we had no information on screening behaviors, which have been found to significantly impact cervical cancer mortality.30–31 While none of these factors impact the internal validity of the analysis, they do have implications for generalizabililty of the findings.

On the other hand, this investigation has many strengths. Because we were using data from the state cancer registry, we had a large number of cervical cancer cases, thus allowing for the stratified analyses presented. In addition, we were able to examine cervical cancer mortality disparities in a large geographical region with a large proportion of rural, southeastern AA, a population that, despite its experience of much greater disparities than the rest of the United States, has been chronically understudied and therefore underrepresented in the literature.2

Implications

Overall, this investigation represents an important first step in describing and defining specific populations at increased risk of death from cervical cancer. In addition, these findings emphasize the need for intervention into the myriad of factors ranging from the biological and genetic to the environmental and structural barriers impacting cervical cancer mortality. These results may help providers and other health professionals recognize the disproportionate burden suffered by AA women and suggest avenues of intervention that could reduce incidence, mortality, or both.

Summary

South Carolina (SC) has some of the largest health disparities in the nation, in particular cancer mortality rates that disfavor African Americans (AA) in comparison to European Americans (EA) with 37% higher incidence and 61% higher mortality rates for AA women compared to EA women. Consequently, the purpose of this investigation was to examine and compare the impact of race on survival among cervical cancer patients in SC.

Data from the SC Central Cancer Registry on all AA and EA cervical cancer patients in SC were analyzed for this investigation. All women greater than 19 years of age with a histopathologically-confirmed cervical neoplasm were included. Kaplan Meier survival curves were calculated and compared for each racial group using the log rank test statistic.

Significant were noted for alcohol use, grade, histology, marital status, and vital status. AA women with cervical cancer had significantly decreased survival compared to EA women (49% vs 66%, p < 0.01). This same trend was noted for all grade, histology, and stage types.

We found significantly decreased survival among AA women with cervical cancer compared to EA women, which persisted even among AA and EA women with the same disease stage, grade, or histology. The causes of these disparities are most likely multi-faceted and interdependent.

These findings emphasize the need for intervention into the myriad of factors ranging from the biological and genetic to the environmental and structural barriers impacting cervical cancer mortality.

Acknowledgments

The authors with to acknowledge the Community Network (SCCDCN) through grant number 1 U01 CA114601-01 from the National Cancer Institute (Community Networks Program).

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2008. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hebert JR, Elder K, Ureda JR. Meeting the challenges of cancer prevention and control in South Carolina: Focus on seven cancer sites, engaging partners. J South Carolina Med Assoc. 2006;102:177–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health and Environmental Control of South Carolina. Cancer Incidence in South Carolina. Electronic data source: http://scangis.dhec.sc.gov/scan/cancer/2004.

- 4.Brandt HM, Modayil MV, Hurley D, Pirisi-Creek LA, Johnson MG, Davis J, Mathur SP, Hebert JR. Cervical cancer disparities in South Carolina: An update of early detection, special programs, descriptive epidemiology, and emerging directions. J South Carolina Med Assoc. 2006;102:223–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howell E, Chen Y, Concato J. Differences in cervical cancer mortality among black and white women. Obstet Gynecol. 1999 October 15;94(4):509–15. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00334-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel D, Barnholtz-Sloan J, Patel M, Malone J, Chuba P, Schwartz K. A population-based study of racial and ethnic differences in survival among women with invasive cervical cancer: analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data. Gynecologic Oncology. 2005 October;97(2):550–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brooks SE, Chen TT, Ghosh A, Mullins CD, Gardner JF, Baquet CR. Cervical cancer outcomes analysis: impact of age, race, and comorbid illness on hospitalizations for invasive carcinoma of the cervix. Gynecologic Oncology. 2000 October;79(1):107–15. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coker AL, Du XL, Fang S, Eggleston KS. Socioeconomic status and cervical cancer survival among older women: findings from the SEER-Medicare linked data cohorts. Gynecologic Oncology. 2006 August;102(2):278–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coker AL, Eggleston KS, Du XL, Ramondetta L. Ethnic disparities in cervical cancer survival among medicare eligible women in a multiethnic population. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 2001 January;(1) doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e318197f343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eggleston KS, Coker AL, Williams M, Tortolero-Luna G, Martin JB, Tortolero SR. Cervical cancer survival by socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and place of residence in Texas, 1995–2001. Journal of Women’s Health. 2006 October;15(8):941–51. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farley JH, Hines JF, Taylor RR, Carlson JW, Parker MF, Kost ER, Rogers SJ, Harrison TA, Macri CI, Parham GP. Equal care ensures equal survival for African-American women with cervical carcinoma. Cancer. 1915 February 1;91(4):869–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenwald HP, Polissar NL, Dayal HH. Race, socioeconomic status and survival in three female cancers. Ethnicity & Health. 1996 March;1(1):65–75. doi: 10.1080/13557858.1996.9961771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu T, Wang X, Waterbor JW, Weiss HL, Soong SJ. Relationships between socioeconomic status and race-specific cervical cancer incidence in the United States, 1973–1992. Journal of Health Care for the Poor & Underserved. 1998 November;9(4):420–32. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgan MA, Behbakht K, Benjamin I, Berlin M, King SA, Rubin SC. Racial differences in survival from gynecologic cancer. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1996 December;88(6):914–8. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(96)00342-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mundt AJ, Connell PP, Campbell T, Hwang JH, Rotmensch J, Waggoner S. Race and clinical outcome in patients with carcinoma of the uterine cervix treated with radiation therapy. Gynecologic Oncology. 1998 November;71(2):151–8. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.5203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy M, Goldblatt P, Thornton-Jones H, Silcocks P. Survival among women with cancer of the uterine cervix: influ -ence of marital status and social class. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 1990 December;44(4):293–6. doi: 10.1136/jech.44.4.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Polednak AP. Cancer mortality in a higher-income black population in New York State. Comparison with rates in the United States as a whole. Cancer. 1990 October 1;66(7):1654–60. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19901001)66:7<1654::aid-cncr2820660734>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samelson EJ, Speers MA, Ferguson R, Bennett C. Racial differences in cervical cancer mortality in Chicago. Am J Public Health. 1994 June;84(6):1007–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.6.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shelton D, Paturzo D, Flannery J, Gregorio D. Race, stage of disease, and survival with cervical cancer. Ethnicity & Disease. 1992;2(1):47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Movva S, Noone AM, Banerjee M, Patel DA, Schwartz K, Yee CL, Simon MS. Racial differences in cervical cancer survival in the Detroit metropolitan area. Cancer. 2008;112(6):1264–71. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brookfield K, Cheung M, Lucci J, Fleming L, Koniaris L. Disparities in Survival Among Women With Invasive Cervical Cancer. Cancer. 2009 January 1;115(1):166–78. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.SCBCB O. South Carolina Statistical Abstract 2007. 2007 Available from: URL: http://www.ors.state.sc.us.

- 23.South Carolina Central Cancer Registry (SCCCR) Survival Database: Cervical_ dec2008.sas7bdat, South Carolina Department of Health and Environment Control, Division of Public Health Statistics and Information Services, South Carolina Central Cancer Registry, based on the August 2008 cancer incidence (1996–2005) and cancer mortality (1996–2006) linked file. 2009. Ref Type: Data File

- 24.World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. 3. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. 2. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Center for Health Statistics. National Death Index. 2007 Ref Type: Data File. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Social Security Administration. Death Master File. 2007 Ref Type: Data File. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson CE, Mues KE, Mayne SL, Kiblawi AN. Cervical cancer screening among immigrants and ethnic minorities: a systematic review using the Health Belief Model. [Review] [73 refs] Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease. 2008 July;12(3):232–41. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e31815d8d88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eggleston KS, Coker AL, Das IP, Cordray ST, Luchok KJ. Understanding barriers for adherence to follow-up care for abnormal pap tests. [Review] [44 refs] Journal of Women’s Health. 2007 April;16(3):311–30. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yabroff KR, Lawrence WF, King JC, Mangan P, Washington KS, Yi B, Kerner JF, Mandelblatt JS. Geographic disparities in cervical cancer mortality: what are the roles of risk factor prevalence, screening, and use of recommended treatment?. [Review] [123 refs] Journal of Rural Health. 2005;21(2):149–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loerzel VW, Bushy A. Interventions that address cancer health disparities in women. Family & Community Health. 2005 January;28(1):79–89. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200501000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Basen-Engquist K, Paskett ED, Buzaglo J, Miller SM, Schover L, Wenzel LB, Bodurka DC. Cervical cancer. [Review] [30 refs] Cancer. 2001 November 3;98(9 Suppl):2009–14. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cates JR, Brewer NT, Fazekas KI, Mitchell CE, Smith JS. Racial differences in HPV knowledge, HPV vaccine acceptability, and related beliefs among rural, southern women. Journal of Rural Health. 2009;25(1):93–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farley JH, Hines JF, Taylor RR, Carlson JW, Parker MF, Kost ER, Rogers SJ, Harrison TA, Macri CI, Parham GP. Equal care ensures equal survival for African-American women with cervical carcinoma. Cancer. 1915 February 1;91(4):869–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith KR, Waitzman NJ. Effects of marital status on the risk of mortality in poor and non-poor neighborhoods. Annals of Epidemiology. 1997 July;7(5):343–9. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(97)00031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.South Carolina Cancer Alliance. South Carolina Cancer Plan. 2004 [Google Scholar]