Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Although examination under anaesthesia and panendoscopy (EUAP) has traditionally been used in the assessment of patients presenting with oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), the era of modern medicine with its advanced imaging techniques has meant that the indications for this technique have potentially reduced.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

In an attempt to quantify the current use of EUAP in the UK, a structured telephone questionnaire was undertaken of 50 maxillofacial units. Information was gathered regarding whether the technique was adopted on a routine or selective basis. Likewise perceived disadvantages were sought.

RESULTS

Twenty-two units (44%) carried out EUAP on all patients presenting with oral cavity and oropharyngeal SCC. Of the remaining 28 units, all employed EUAP on a selective basis, the most commonly for the assessment of the primary tumour. The most common perceived disadvantage of carrying out EUAP routinely was its potential to increase the waiting time to definitive treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

These results suggest a gradual move towards the selective use of EUAP in patients presenting with oral cavity and oropharyngeal SCC.

Keywords: Head and neck malignancy, Squamous cell carcinoma, Panendoscopy

Examination under anaesthesia and panendoscopy (EUAP) is widely used in the assessment of patients presenting with oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Proponents justify its use on a number of grounds. Traditionally, it has been said that it allows accurate assessment of the index tumour although enhanced imaging modalities have lessened that argument. Panendoscopy may also detect simultaneous primary tumours, although a number of studies suggest that prevalence of such tumours is lower than originally thought, particularly in the non-symptomatic individual. The short anaesthetic that EUAP employs can be used to predict a patient's response to prolonged operative intervention but in the modern era ‘test anaesthetics’ are of questionable value. The procedure also gives the opportunity to perform biopsies of what in some circumstances is an inaccessible tumour, as well as attending to the dentition if radiotherapy is to be employed and the possibility of osteoradionecrosis is to be minimised.

Since EUAP can increase the time to definitive treatment and also has cost implications, we sought to obtain information about its current usage in the management of patients presenting with oral cavity and oropharyngeal SCC within the UK.

Subjects and Methods

There are 34 tumour networks that serve the population of the UK; to ensure a representative sample and avoid bias, these networks were used as a geographical basis for contacting oral and maxillofacial units involved in the management of oral cavity and oropharyngeal SCC. Consultants and specialist registrars in each unit were interviewed using a structured telephone questionnaire with the interviews being undertaken by two of the authors (CJK, BB). The clinicians were initially asked whether the unit performed EUAP and whether this was carried out routinely or on a selective basis. For the purposes of the study ‘panendoscopy’ was defined as the endoscopy of the nasal cavity, nasopharynx, oropharynx, larynx and upper oesophagus, with or without bronchoscopy. The indications for EUAP were obtained in terms of index tumour assessment, detection of simultaneous disease in the asymptomatic individual and its use as a ‘test anaesthetic’. In units with a selective approach, further information regarding that process was elicited, e.g. did a patient's exposure to risk factors influence its use? Finally, the perceived advantages of EUAP were obtained where relevant.

Results

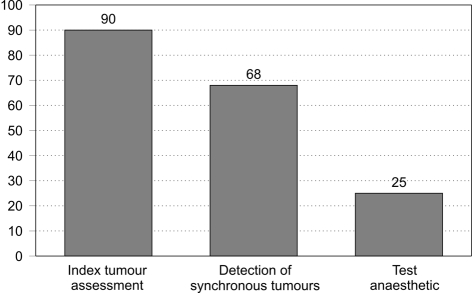

Representatives from 50 maxillofacial units were questioned. Of these, 22 (44%) employed EUAP on all patients. Of the remaining 28 units, the most common indication for EUAP was the assessment of the index tumour (Fig. 1). Around one in four units still felt that the use of EUAP as a ‘test anaesthetic’ was justified.

Figure 1.

Reasons for EUAP use in units adopting a selective approach (% of units surveyed).

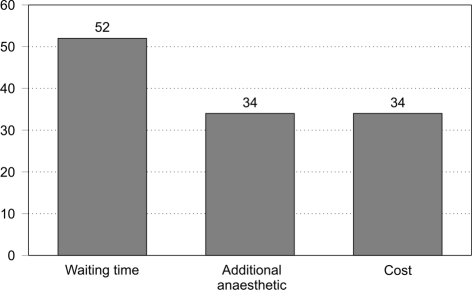

For those units adopting a selective approach, the most commonly perceived disadvantage of routine EUAP was a potential increase in waiting time to definitive treatment (Fig. 2). One-third of units also expressed concern regarding the cost implications of a second anaesthetic.

Figure 2.

Perceived disadvantages of EUAP (% of units surveyed).

Discussion

EUAP was introduced in the management of head and neck malignancy in the late 1970s and is still used in many units throughout the world on a routine basis. It requires little in the way of equipment and remains less expensive than some of the alternative modes of staging patients such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron imaging tomography. The morbidity and mortality is low.1 In this day and age, it may still be the most sensitive way of detecting superficial mucosal lesions.2 There is, however, increasing evidence that the incidence of simultaneous malignancies may be in the low single figures.3–5

The routine use of EUAP as a diagnostic and screening tool for the primary assessment of patients with head and neck cancer continues to be controversial. A number of retrospective and prospective studies have variably supported its usefulness. Davidson et al.3 reviewed a group of 224 patients with both newly diagnosed and recurrent tumours at a variety of head and neck sites. All were investigated with panendoscopy. Of the 154 patients with newly diagnosed tumours, the incidence of simultaneous primary disease was just 2.6% (four patients). No patient had oesophageal disease. Only one of the four simultaneous tumours was diagnosed at EUAP with the remainder being evident on either physical examination or plain radiography. Stoeckli et al.,4 in an evaluation of 358 patients presenting with previously untreated SCC of the upper aerodigestive tract, demonstrated an incidence of second primary tumours of 6.4% whereas Hujala et al.5 found eight patients with simultaneous second primaries in a review of 203 consecutively treated patients (3.9%). All of these studies included multiple primary sites.

To justify the routine use of EUAP in patients presenting with oral cavity and oropharyngeal malignancy, a number of issues need to be considered. It must add significantly to the diagnosis of simultaneous primary tumours when combined with routine physical examination and radiological investigations. A large meta-analysis of 24 studies reported the incidence of simultaneous and metachronous malignancies in over 40,000 head and neck patients.6 The overall rate of second primaries in this group was 14.2%, of which only 4% were simultaneous lesions. Of these simultaneous tumours, 35% occurred in the head and neck and were detectable on routine physical examination. A further 25% arose in the lung and would not have been detected by routine bronchoscopy but instead by either CT or chest X-ray. A further 31% arose outwith the head and neck and just 9% arose in the oesophagus. The adoption of symptom-directed endoscopies would have detected most of these. Based on this and similar studies, one can estimate that, for every 1000 patients presenting with a new head and neck primary lesion, 40 will have simultaneous primary tumours. Of these, 14 will occur in the head and neck and be detectable by physical and fibre-optic examination, 10 will occur in the lung and be detectable by radiological means and a further 13 will occur outside the aerodigestive tract. Three will occur in the oesophagus and be potentially detectable by oesophagoscopy. If such assumptions are correct, although EUAP has a greater yield over physical examination combined with routine radiological investigations, the actual gain for every 1000 patients undergoing panendoscopy will be the detection of just three oesophageal malignancies.

The next question to be addressed is whether the discovery of a second primary tumour changes the primary treatment of an individual patient. The treatment of early, ‘silent’, simultaneous primaries may be relatively simple whereas the demonstration of more extensive second tumours not only influences prognosis but may also avoid unnecessary and often mutilating treatment at the primary site. Panosetti et al.7 demonstrated that the discovery of a simultaneous tumour altered the management in 50% of their patients. The same authors reviewed the impact on survival of patients with simultaneous versus metachronous second primary tumours. Patients who were initially seen with simultaneous primary tumours had a 5-year survival of 18% compared with 55% for those patients with metachronous tumours. This suggests that the overall survival of patients with detectable, simultaneous, primary tumours is poor.

The final issues that need to be addressed in justifying the routine use of EUAP in patients presenting with oral cavity and oropharyngeal SCC are those of its usefulness as a ‘test anaesthetic’ and its suitability, or otherwise, in assessing the index tumour. In the modern era, clinicians' reliance on ‘test anaesthetics’ to predict a patient's response to the physiological trauma of operative intervention has reduced. Many patients presenting with head and neck malignancies have significant co-morbidities in terms of cardiac or pulmonary disease. Pre-optimisation of such patients with selective use of non-invasive investigations, such as quantitative echocardiography and cardiopulmonary exercise testing, have meant that the likely effect of anaesthesia on a patient's physiological function can be accurately predicted prior to surgery. Perhaps, the only useful aspect of ‘test anaesthetics’ that remains is that it allows potential airway problems secondary to tumour mass effect to be identified. Reliance on examination under anaesthesia to assess the resectability, or otherwise, of posteriorly-based tumours was widespread a decade or so ago. Enhanced cross-sectional imaging modalities have lessened that reliance, such that today the vast majority of operations can be confidently performed solely on the basis of images obtained by CT or MRI.8 The gradual move towards chemoradiation to preserve function in such posterior tumours also obviates the argument for EUAP to assess resectability, although of loss of the opportunity to attend to the dentition in such instances should not be overlooked.

Although there is relatively little in the literature that specifically addresses the cost-effectiveness of EUAP, a theoretical model based on the low yield of simultaneous primary tumours in most studies suggests that it is unlikely to be so.1,9 In the modern era of medicine, cost-effectiveness is an increasing issue with clinicians often having to justify interventions on this basis.10–12 It certainly seems within the UK that a more selective approach to EUAP is gradually developing; although this may, in part, be due to financial restrictions, there is certainly a medical evidence-base to support this move. It is likely that, as this body of evidence increases, the move away from the routine use of EUAP in all patients with oral cavity and oropharyngeal SCC will continue leaving it as a selective screening tool for high-risk individuals or those who present in a symptomatic manner.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that, in the UK, there has been a gradual move away from the routine use of EUAP in the assessment of patients presenting with oral cavity and oropharyngeal SCC. Much of the disease that presents in this anatomical site is accessible to biopsy under local anaesthesia alone. The wide-spread use of flexible endoscopic examination in the out-patient department is adequate in most instances to visualise correctly the craniocaudal extent of a tumour with CT or MRI completing the clinical staging.13,14 The use of PET/CT in patients with newly diagnosed head and neck cancer demonstrates a high positive predicative value in detecting simultaneous lesions and further limits the need for EUAP.15–17

References

- 1.Glaws WR, Etzkorn KP, Wening BL, Zulfiqar H, Wiley TE, Watlins JL. Comparison or rigid and flexible esophagoscopy in the diagnosis of esophageal disease: diagnostic accuracy, complication and cost. Ann Otol Rhino Laryngol. 1996;105:262–6. doi: 10.1177/000348949610500403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmid DT, Stoeckli SJ, Bandhauer F, Huguenin P, Schmid S, et al. Impact of positron emission tomography on the initial staging and therapy in locoregional advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:888–91. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200305000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson J, Gilbert R, Irish J, Witterick I, Brown D, et al. The role of panendoscopy in the management of mucosal head and neck malignancy – a prospective evaluation. Head Neck. 2000;22:449–54. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200008)22:5<449::aid-hed1>3.0.co;2-l. discussion 454–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stoeckli SJ, Zimmermann R, Schmid S. Role of routine panendoscopy in cancer of the upper aerodigestive tract. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;124:208–12. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.112311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hujala K, Sipliä J, Grenman R. Panendoscopy and simultaneous second primary tumors in head and neck cancer patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262:17–20. doi: 10.1007/s00405-004-0743-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haughey BH, Gates GA, Arfken CL, Harvey J. Meta-analysis of second malignant tumors in head and neck cancer: the case for an endoscopic screening protocol. Ann Otol Rhino Laryngol. 1992;101:105–12. doi: 10.1177/000348949210100201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panosetti E, Luboinski B, Mamelle G, Richard JM. Multiple simultaneous and metachronous cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract: a nine-year study. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:1267–73. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198912000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwai H, Kyomoto R, Ha-Kawa SK, Lee S, Yamashita T. Magnetic resonance determination of tumor thickness as predictive factor of cervical metastasis in oral tongue carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:457–61. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200203000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim MK, Deschler DG, Hayden RE. Flexible esophagoscopy as part of routine panendoscopy in ENT resident and fellowship training. Ear Nose Throat J. 2001;80:49–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeannon JP, Abbs I, Calman F, Gleeson M, Lyons A, et al. Implementing the National Institute of Clinical Excellence improving outcome guidelines for head and neck cancer: developing a business plan with reorganisation of head and neck cancer services. Clin Otolaryngol. 2008;33:149–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2008.01637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Agthoven M, van Ineveld BM, de Boer MF, Leemans CR, Knegt PP, et al. The costs of head and neck oncology: primary tumours, recurrent tumours and long-term follow-up. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:2204–11. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00292-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bradley PJ, Zutshi B, Nutting CM. An audit of clinical resources available for the care of head and neck cancer patients in England. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2005;17:604–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrou M, Mukherji SK. Extracranial head and neck neoplasms: role of imaging. Cancer Treat Res. 2008;143:93–117. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-75587-8_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van den Brekel MW, Castelijns JA, Snow GB. The role of modern imaging studies in staging and therapy of head and neck neoplasms. Semin Oncol. 1994;21:340–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fakhry, Barberet M, Lussato D, Mundler O, Giovanni A, Zanaret M. Role of 18-FDG PET/CT in the initial staging of head and neck cancers. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord) 2007;128:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fakhry, Lussato D, Jacob T, Giorgi R, Giovanni A, Zanaret M. Comparison between PET and PET/CT in recurrent head and neck cancer and clinical implications. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264:531–8. doi: 10.1007/s00405-006-0225-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hojgaard L, Specht L. PET/CT in head and neck cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:1329–33. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0373-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]