Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Patients with lymphadenopathy are commonly referred to general surgeons for diagnostic lymph node biopsy. We were concerned at potential long waits for this service in our hospital and thus wanted to compare the efficiency of written and telephone referral with a view to identifying the optimum care pathway for these patients.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Sixty patients were included in a 2-year retrospective review (excluding referrals associated with breast lumps which were managed separately). Hospital Episode Statistics data were used to analyse notes for the source and method of referral, waiting time to biopsy, clinic attendance and diagnosis.

RESULTS

Of referrals, 33% were from haematology and 28% from general practice. Overall, 47% of patients were referred by letter; of these, 64% were seen in clinic before biopsy. Personal referral between clinicians, by direct discussion, e-mail or fax led to a mean wait of 4 days, compared to 51 days when patients were referred by letter. Clinic attendance had no significant bearing on diagnostic accuracy or complication rate. Neoplasia accounted for 43% of diagnoses and infection (including four cases of tuberculosis) for 10%. Of biopsies, 33% showed benign changes, 8% were unrecorded and 5% were incorrect.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, 43% of biopsies revealed malignancy and we advise that lymph node biopsy requests should be managed on a fast-track pathway, expedited by direct personal request. Following this study, we have implemented a fast-track pathway for such patients.

Keywords: Lymphadenopathy, Health services administration, Clinical pathways

Introduction

Palpable lymphadenopathy is a common reason for referral to secondary care. Subsequent investigation often involves lymph node biopsy; surgical teams performing the procedure must prioritise requests from the numerous departments that initially assess these patients. A variety of referral pathways have, therefore, evolved.

Several groups have sought to bring more coherence to the management of patients with lymphadenopathy. Some have designed clinical algorithms rationalising the decision to proceed to lymph node biopsy, hoping to reduce the number of unnecessary procedures performed;1,2 others have promoted generic neck lump clinics.3–8 None have achieved a unifying solution that has found wide-spread acceptance.

Seeking to improve the efficiency of our own lymphadenopathy service, we investigated whether any one of the multiple referral pathways within our institution was significantly more effective than its competitors. The patient records of those who had undergone a peripheral lymph node biopsy in our hospital over a 2-year period were examined, assessing for: (i) waiting time from surgical referral to biopsy; (ii) referral source; (iii) method of referral; (iv) attendance in surgical clinic; and (v) diagnosis.

Patients and Methods

The hospital database of the Whittington Hospital NHS Trust was searched for details of adult patients who had undergone lymph node biopsy between May 2005 and May 2007. The relevant clinical records were examined, and those patients who had had retroperitoneal, breast, mediastinal or ‘sentinel’ lymph nodes excised were excluded, as were those who had incidental lymph nodes sampled at the time of an open or laparoscopic operation. From the remaining records, pertinent data were collected for: (i) waiting time from surgical referral to biopsy; (ii) referral source; (iii) method of referral; (iv) attendance in surgical clinic; and (v) diagnosis. The primary goal of the paper was to identify if any significant relationship existed between referral method and waiting time.

Results

Sixty-seven adult patients were recorded in the hospital episode statistics data as having peripheral lymph node biopsies during the study period and 90% (60 of 67) of patient records could be analysed.

Of these, 33% (20 of 60) of lymph nodes were sampled from the cervical chain, 27% (16 of 60) from the axilla, and 22% (13 of 60) from the inguinal region. Of patients with cervical lymphadenopathy, 10% (2 of 20) were seen in the ENT department for examination of the upper aerodigestive tract prior to biopsy. No patients had fine needle aspiration cytology prior to biopsy.

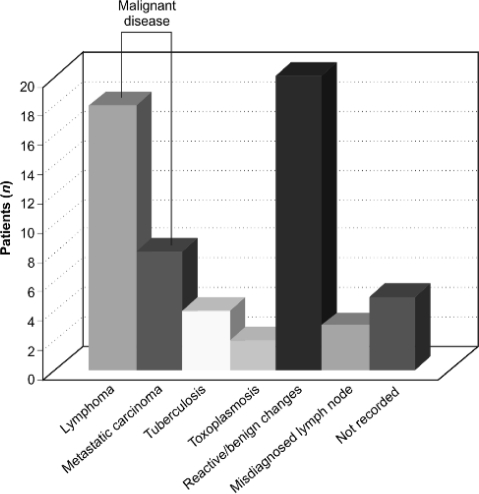

Neoplasia (carcinoma or lymphoma) accounted for 43% (26 of 60) of diagnoses; infectious disease for 10% (6 of 60), including 4 cases of tuberculosis and 2 of toxoplasmosis; 33% (20 of 60) biopsies showed benign changes or Kikuchi's disease; 5% (3 of 60) lymphadenopathy diagnoses were incorrect; and 8% (5 of 60) of biopsy results were unrecorded (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Histological diagnosis of peripheral superficial lymphadenopathy at the Whittington Hospital, 2005–2007.

The predominant referral sources were the haematology department (33%; 20 of 60) and general practice (28%; 17 of 60). Other referrals came from the acute medical team on-call (12%; 7 of 60), respiratory medicine (5%; 3 of 60), and the emergency department (5%; 3 of 60). Of the frequent referral sources, it was the acute medical team whose referrals most often ended in a diagnosis of neoplasia or tuberculosis (86%; 6 of 7), followed by haematology (55%, 11 of 20) and then general practice (53%; 9 of 17).

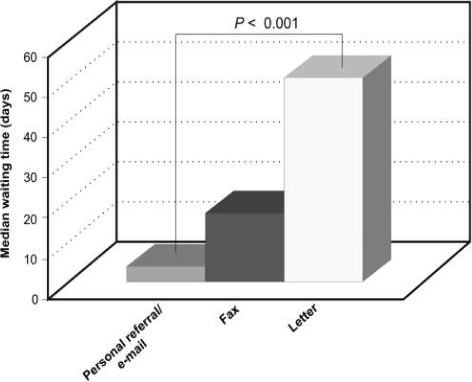

Overall, 47% (28 of 60) of patients were referred to the surgeons by letter, 45% (27 of 60) by personal discussion or e-mail, and 8% (5 of 60) by fax. Waiting times from referral to biopsy were often substantial. Those patients referred by post waited a median of 51 days for their biopsy; this dropped to a median of 17 days for faxed referrals. Patients whose referral was made in person or by e-mail waited a median of 4 days before their biopsy. Personal or e-mailed referral was, therefore, associated with a significantly shorter time to biopsy (P < 0.001, Mann–Whitney U-test; Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Waiting times to lymph node biopsy by referral method.

Patients referred by letter were often seen in surgical out-patient clinic (64%; 18 of 28) whereas all those referred in person proceeded straight to biopsy. Attendance in the surgical out-patient clinic prior to biopsy had no bearing on diagnostic accuracy: of the five incorrect diagnoses of lymphadenopathy, two had been seen in clinic and three had not. Nor did clinic attendance reduce peri-operative complications: of the four lymph node biopsies recorded as difficult, or resulting in postoperative superficial wound infection, two (50%) of the patients had been seen in clinic.

Discussion

This study contributes to the understanding of service provision for peripheral lymphadenopathy, which is incoherent and poorly rationalised.9,10 Wide-spread delays have been reported, both before biopsy and in informing patients of their diagnosis.9 Of patients in this study, 43% had a diagnosis of neoplastic disease; it is imperative that these patients receive a rapid, accurate diagnosis and proceed quickly to treatment. Delay to diagnosis is a real concern: the time taken by a hospital team – after referral – to reach the diagnosis of lymphoma can outweigh the time spent in primary care.11 This diagnostic delay can also exceed the subsequent delay to treatment.12

The use of dedicated lump clinics has been advocated to improve services for patients with lymphadenopathy.3–8 Little is known, however, about effective improvements within the context of existing care arrangements. This study is the first to address the effect of committing patients to a particular referral pathway within an established service.

Numerous complex patient pathways have been described in hospitals lacking a distinct referral pathway for patients with lymphadenopathy.9,10,13 This results in unacceptable variation: patients referred to general surgery or ENT departments have longer times to diagnosis.13 Standardised guidelines for lymphadenopathy assessment would facilitate the appropriate use of investigations other than lymph node biopsy, and a rapid diagnosis. Examination of the aerodigestive tract, to exclude head and neck malignancies as causes of cervical lymphadenopathy,14 and fine needle aspiration cytology were both under-utilised in this study, although the role of aspiration cytology remains unclear.15–19

Routine out-patient surgical review prior to biopsy appeared of little value, with no effect on diagnostic accuracy or peri-operative complications. In contrast, direct communication between the referring and surgical teams significantly reduced waiting time before the procedure. The use of a fast-track referral route, similar to the ‘Two Week Wait’ pathway for patients with suspected cancer20 should, therefore, reduce the diagnostic delay. Direct booking arrangements for other day-case procedures have already been shown to reduce waiting times and provide a service acceptable to patients.21 As a result of this study, our hospital has developed a direct-booking, fast-track pathway by which consultants in haematology or respiratory medicine can arrange day-case lymph node biopsies without prior discussion with a surgeon.

Despite the range of diseases identified in this and other series,22–25 many lymph node biopsies are still performed on those who have self-limiting causes of their lymphadenopathy. Technologies used to select patients for invasive investigation have been described.26–29 However, it is unlikely that the selection of patients for biopsy will be successfully optimised without more formal guidance for lymphadenopathy assessment, whether or not that assessment is carried out within a single multidisciplinary clinic. Mechanisms for reducing the time to biopsy can then be employed to better effect.

Conclusions

This study shows that the management of lymphadenopathy at one hospital lacked cohesion. There was significant variation in waiting time, dependent on the method of referral. Alterations in service provision are essential if diagnostic and therapeutic delays are to be avoided. With 43% of lymphadenopathy in this study caused by malignancy, these changes should be prioritised.

References

- 1.Vassilakopoulos TP, Pangalis GA. Application of a prediction rule to select which patients presenting with lymphadenopathy should undergo a lymph node biopsy. Medicine (Baltimore) 2000;79:338–47. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200009000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tokuda Y, Kishaba Y, Kato J, Nakazato N. Assessing the validity of a model to identify patients for lymph node biopsy. Medicine (Baltimore) 2003;82:414–8. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000100047.15804.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gregory RK, Cunningham D, Fisher TA, Rhys-Evans P, Middleton GW, et al. Investigating lymphadenopathy – report on the first 12 months of the lymph node diagnostic clinic at the Royal Marsden Hospital. Postgrad Med J. 2000;76:566–8. doi: 10.1136/pmj.76.899.566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCombe A, George E. One-stop neck lump clinic. Clin Otolaryngol. 2002;27:412. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.2002.00580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kishore A, Stewart CJR, McGarry GW, MacKenzie K. One stop neck lump clinic; phase 2 of audit. How are we doing? Clin Otolaryngol. 2001;26:495–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.2001.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray A, Stewart CJR, McGarry GW, MacKenzie K. Patients with neck lumps: can they be managed in a ‘one-stop’ clinic setting? Clin Otolaryngol. 2000;25:471–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.2000.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith OD, Ellis PDM, Bearcroft PWP, Berman LH, Grant JW, Jani P. Management of neck lumps – a triage model. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2000;82:223–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vowles RH, Ghiacy S, Jefferis AF. A clinic for the rapid processing of patients with neck masses. J Laryngol Otol. 1998;112:1061–4. doi: 10.1017/s002221510014246x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moor JW, Murray P, Inwood J, Gouldesbrough D, Bem C. Diagnostic biopsy of lymph nodes of the neck, axilla and grorhyme, reason or chance? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2008;90:221–5. doi: 10.1308/003588408X242105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsikoudas A. Management pathways and the surgical diagnosis of tuberculous lymphadenitis: can they be improved? The Bradford experience. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2003;65:261–5. doi: 10.1159/000075223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howell DA, Smith AG, Roman E. Lymphoma: variations in time to diagnosis and treatment. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2006;15:272–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Summerfield GP, Carey PJ, Galloway MJ, Tinegate HN. An audit of delays in diagnosis and treatment of lymphoma in district hospitals in the northern region of the United Kingdom. Clin Lab Haematol. 2000;22:157–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2257.2000.00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howell DA, Smith AG, Roman E. Referral pathways and diagnosis: UK Government actions fail to recognize complexity of lymphoma. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2007;16:529–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2007.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barakat M, Flood IM, Oswal VH, Ruckley RW. The management of a neck mass: presenting feature of an asymptomatic head and neck primary malignancy? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1987;69:181–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birchall MA, Walsh-Waring GP, Stafford ND. Malignant neck lumps: a measured approach. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1991;73:91–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lioe TF, Elliott H, Allen DC, Spence RA. The role of fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) in the investigation of superficial lymphadenopathy; uses and limitations of the technique. Cytopathology. 1999;10:291–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2303.1999.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martins MR, Santos Gda C. Fine-needle aspiration cytology in the diagnosis of superficial lymphadenopathy: a 5-year Brazilian experience. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34:130–4. doi: 10.1002/dc.20373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malami SA. Uses and limitations of fine needle aspiration cytology in the diagnostic work-up of patients with superficial lymphadenopathy. Nig Q J Hosp Med. 2007;17:144–7. doi: 10.4314/nqjhm.v17i4.12695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris-Stiff G, Cheang P, Key S, Verghese A, Harvard TJ. Does the surgeon still have a role to play in the diagnosis and management of lymphomas? World J Surg Oncol. 2008;6:13. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department of Health. Referral guidelines for suspected cancer. London: DH; 2000. < http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4008746> [Accessed 17 July 2008] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sri-Ram K, Irvine T, Ingham Clark CL. A direct booking hernia service – a shorter wait and a satisfied patient. Ambul Surg. 2006;12:113–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedig EE, McClure SP, Wilson WR, Banks PR, Washington JA. Clinico-histologic-microbiologic analysis of 419 lymph node biopsy specimens. Rev Infect Dis. 1986;8:322–8. doi: 10.1093/clinids/8.3.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anthony PR, Knowles SS. Lymphadenopathy as a primary presenting sign: a clinico-pathological study of 228 cases. Br J Surg. 1983;70:412–4. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800700708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee YTN, Terry R, Lukes RJ. Biopsy of peripheral lymph nodes. Am Surg. 1982;48:536–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee YTN, Terry R, Lukes RJ. Lymph node biopsy for diagnosis: a statistical study. J Surg Oncol. 1980;14:53–60. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930140108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tschammler A, Beer M, Hahn D. Differential diagnosis of lymphadenopathy: power Doppler vs color Doppler sonography. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:1794–9. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1325-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steinkamp HJ, Wissgott C, Rademaker J, Felix R. Current status of power Doppler and color Doppler sonography in the differential diagnosis of lymph node lesions. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:1785–93. doi: 10.1007/s003300101111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dragoni F, Cartoni C, Pescarmona E, Chiarotti F, Puopolo M, et al. The role of high resolution pulsed and color Doppler ultrasound in the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant lymphadenopathy: results of multivariate analysis. Cancer. 1999;85:2485–90. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990601)85:11<2485::aid-cncr26>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulte-Altedorneburg G, Demharter J, Linné R, Droste DW, Bohndorf K, Bücklein W. Does ultrasound contrast agent improve the diagnostic value of colour and power Doppler sonography in superficial lymph node enlargement? Eur J Radiol. 2003;48:252–7. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(03)00076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]