Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To determine the opinions of medical professionals, legal professionals, and patients regarding the withdrawal of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) and pacemaker therapy at the end of life.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS: A survey regarding 5 cases that focused on withdrawal of ICD or pacemaker therapy at the end of life was constructed and sent to 5270 medical professionals, legal professionals, and patients. The survey was administered from March 1, 2008, to March 1, 2009.

RESULTS: Of the 5270 recipients of the survey, 658 (12%) responded. In a terminally ill patient requesting that his ICD be turned off, most legal professionals (90% [63/70]), medical professionals (98% [330/336]), and patients (85% [200/236]) agreed the ICD should be turned off. Most legal professionals (89%), medical professionals (87%), and patients (79%) also considered withdrawal of pacemaker therapy in a non–pacemaker-dependent patient appropriate. However, significantly more legal (81%) than medical professionals (58%; P<.001) or patients (68%, P=.02) agreed with turning off a pacemaker in the pacemaker-dependent patient. A similar number of legal professionals thought turning off a device was legal regardless of whether it was an ICD or pacemaker (45% vs 38%; P=.50). However, medical professionals were more likely to perceive turning off an ICD as legal than turning off a pacemaker (85% vs 41%; P<.001).

CONCLUSION: Most respondents thought device therapy should be withdrawn if the patient requested its withdrawal at the end of life. However, opinions of medical professionals and patients tended to be dependent on the type of device, with turning off ICDs being perceived as more acceptable than turning off pacemakers, whereas legal professionals tended to perceive all devices as similar. Thus, education and discussion regarding managing devices at the end of life are important when having end-of-life discussions and making end-of-life decisions to better understand patients' perceptions and expectations.

Education and discussion of managing devices at the end of life are important when having end-of-life discussions and making end-of-life decisions to understand patients' perceptions and expectations.

ICD = implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; PM = pacemaker

Management of the terminally ill patient has become increasingly complex as the means to keep a patient alive have advanced; patients with illnesses that they would have had no substantial likelihood of surviving 10 years ago may now be kept alive for weeks, months, or even years. Multiple legal cases have focused on the rights of patients, surrogates, and care providers when it comes to both futile and end-of-life care.1-4 Specifically, decisions on many externally provided life-sustaining therapies, including feeding tubes, mechanical ventilation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the event of cardiac arrest, and the administration of intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and external pacing, have typically favored the right of the patient or the surrogate decision maker to refuse and withdraw therapy.

Recent studies have focused on the withdrawal of intracardiac device therapies in terminally ill patients.5-13 One of the difficulties that exists with this subset of patients is that the device may have been present for decades before the patient presented with a terminal or end-of-life event. Furthermore, that event may or may not be related to the reason for which the device was originally placed. Most implantable cardiac devices, including implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) and pacemakers (PMs), are used to prevent morbidity and mortality from underlying cardiac arrhythmias. The role these devices play in patients may range from preventive (as in the case of ICDs implanted for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death) to therapeutic (as in the case of a PM implanted for complete heart block or to avoid symptomatic bradycardia).

Although it is generally accepted that withdrawal of ICD therapies to avoid shocks for ventricular tachyarrhythmias in terminally ill patients is reasonable,5-8 the role of withdrawing PM therapy, especially in a PM-dependent patient, is not as clear.9,14,15 Notably, to our knowledge, no legal cases have focused on the legality of device withdrawal. Nevertheless, a recent expert consensus statement supports the withdrawal of both ICD and PM therapies in terminally ill patients if doing so is consistent with patients' health care–related values, preferences, and goals.16 However, the opinions of patients and legal professionals regarding the ethics and legality of device withdrawal are less clear. Thus, we surveyed medical professionals, legal professionals, and patients to determine opinions regarding the ethicality and legality of withdrawing ICDs and PMs at the end of life.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

Survey Construction

A survey consisting of 5 cases focusing on withdrawal of ICD or PM therapy at the end of life, 3 demographic questions (asking about sex, age range, and profession), and 2 summary questions (asking about the perception of the legality of turning off an ICD vs a PM) was constructed. Four of the cases focused on terminally ill patients at the end of life who wished for either ICD or PM therapy to be withdrawn. A fifth case focused on a terminally ill patient who had no device but whose terminally ill twin brother was to have his PM turned off and thus requested administration of a medication so he could die in a similar way. Cases were each followed by statements related to the case with choices on whether the respondent agreed, had a neutral opinion, or disagreed.

Cases were constructed by 2 investigators (S.J.A., S.K.) and then adjudicated by both cardiac electrophysiologists (D.L.H., S.J.A.) and a medical ethicist (P.S.M.). The decision to include a case and the associated questions was made by consensus among all the authors. (For summary of case stems, see eAppendix 1 in the Supporting Online Material, a link to which is provided at the end of this article.) In many of the cases, 2 separate physicians and a psychiatrist discussed the issue with the patients to ensure that the patient had been presented with multiple opinions on issues related to device management and determine that the patient had clear decision-making capacity.

Survey Administration

Surveys were administered via paper or the Internet after obtaining approval of the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. Surveys were administered from March 1, 2008, to March 1, 2009. Paper versions of the survey were delivered via mail with return envelopes and postage to a total of 428 law school faculty identified from online lists of active faculty at 5 major US law schools. Surveys were also sent to 300 district and federal court judges randomly selected from judicial rosters. However, no judges returned completed surveys, claiming a conflict of interest should they express bias given the possibility that such a case could appear before them in the future. Paper versions were also given to a series of 400 consecutive patients appearing for appointments at the outpatient device clinic at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN. All of these paper versions of the survey were returned to the Survey Research Center at Mayo Clinic,where responses were anonymized and entered into a central database. The Web-based version of the survey was delivered to a roster of 4442 physicians, nurses, and other medical professionals who were active members of the Heart Rhythm Society. Responses to these surveys were also received by the Survey Research Center, anonymized, and included in a central database. The investigators had access only to the final, anonymized database for purposes of statistical analysis.

Statistical Analyses

Responses to survey statements were scaled from 1 to 5: 1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = neutral; 4 = agree; and 5 = strongly agree. Survey responses were analyzed as absolute percentages of the total number of respondents who agreed (ie, answered 4 or 5 to a statement) or disagreed (ie, answered 1 or 2 to a statement). If a survey respondent provided no response to a specific statement, he or she was excluded from the analysis. Dichotomous variables were compared using a χ2 test, and continuous variables were compared using a t test. Subgroup analyses by age, sex, and profession were also performed. P< .05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Survey Respondents

Of 5270 surveyed medical professionals, attorneys, and patients, a total of 658 (12%) responded (54% male; 12% aged 18-30 years; 40% aged 31-50 years; and 48% older than 51 years; Table). Physicians and other medical professionals, including device industry representatives, nurses, and physician assistants, exhibited no significant differences in their responses to any question and thus were analyzed as a single group of medical professionals. Most medical professionals stated that they had been involved in a situation in which a patient or his or her surrogate decision maker had requested turning off an ICD (267/339; 79%) or PM (226/339; 67%). No significant differences in responses were seen within groups when taking into account the sex or age of respondents. (For a summary of responses to each question and each case, see eAppendix 2 in the Supporting Online Material.)

TABLE.

Demographics of Respondents

Withdrawal of ICD Therapy

In the case of a terminally ill patient requesting that his ICD be turned off at the end of life, most legal professionals (90% [63/70]), medical professionals (98% [330/336]), and patients (85% [200/236]) agreed or strongly agreed that an ICD should be turned off because it represented the patient's right to refuse ongoing therapy (eAppendix 2; case 1). However, significantly more patients (7% [16/236]) than medical professionals (1% [5/336]) disagreed with turning off the ICD (P=.001). In fact, significantly more patients (20% [47/236]) and legal professionals (10% [7/70]) thought that turning off the ICD could be considered akin to physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia, whereas few medical professionals believed similarly (3% [9/334]) (P<.001 [patients vs medical professionals]; P=.01 [legal professionals vs medical professionals]). Significantly more legal professionals (37% [23/62]) than medical professionals (12% [40/322]) or patients (18% [41/227]) thought that turning off an ICD was not in the patient's best interests (P<.001 [legal professionals vs medical professionals]; P=.003 (legal professionals vs patients]).

When turning off the ICD is against the personal beliefs of the physician (eAppendix 2; case 5), most patients (59% [133/224]), legal professionals (68% [47/69]), and medical professionals (88% [287/328]) still thought that the ICD should be turned off by the physician. Significantly more legal professionals (51% [36/70]) than medical professionals (13% [43/319]) thought that physicians should not turn off the ICD when doing so was against their personal beliefs and instead should refer the patient to another physician (P<.001). In fact, most medical professionals (73% [233/319]) and patients (53% [116/218]) thought that it would be inappropriate to refuse to turn off the ICD and to instead refer to a colleague who would be willing to do so.

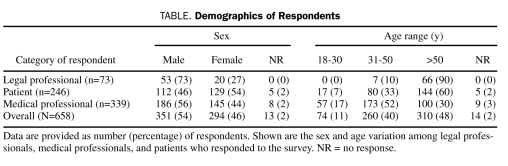

In response to the summary question regarding turning off an ICD in a patient who no longer desires shocks, most medical professionals thought that turning off the ICD was legal and therefore should be carried out (85% [289/339]) (Figure 1). Significantly fewer patients (53% [130/246]) and legal professionals (45% [33/73]) agreed that turning off an ICD was legal (P<.001 [medical professionals vs patients]; P<.001 [medical professionals vs legal professionals]). Legal professionals tended to observe the legal status of turning off an ICD as unclear (29% [21/73]), whereas fewer patients (17% [42/246]) and medical professionals (7% [25/339]) held that opinion (P=.04 [legal professionals vs patients]; P<.001 [legal professionals vs medical professionals]). A minority of patients (7% [17/246]), legal professionals (5% [4/73]), and medical professionals (1% [3/339]) thought that turning off an ICD was akin to physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia.

FIGURE 1.

Perceptions of the legality of withdrawing implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) therapy. Shown is the percentage of medical professionals, legal professionals, and patients who perceived withdrawal of ICD therapy as legal, of unclear legal status, or as akin to physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia or who offered no opinion. All groupwise comparisons were significant (P<.001), except for the comparison between legal professionals and patients, with a similar percentage believing that withdrawal of ICD therapy was akin to physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia. The actual percentage for each group is listed above the respective bar.

Withdrawal of PM Therapy in the Non–PM-Dependent Patient

Most legal professionals (89% [62/70]), medical professionals (87% [294/337]), and patients (79% [188/237]) thought that withdrawal of PM therapy in a non–PM-dependent patient was appropriate based on the express wish of the patient. However, significantly more patients (21% [50/236]) thought that turning off the PM in the non–PM-dependent patient would be akin to physician-assisted death or euthanasia (P=.01 [patients vs legal professionals]; P<.001 [patients vs medical professionals]) (eAppendix 2; case 2). Despite this, few patients (9% [22/237]) disagreed with turning off the PM based on the fact that it represented the patient's wishes. Despite this general consensus on turning off the PM, few agreed that it was in the best interests of the patient (legal professionals: 11% [7/61]; medical professionals: 23% [72/319]; and patients: 36% [83/233]). Legal professionals (44% [27/61]) tended to think that turning off the PM was not in the patient's best interests more often than medical professionals (28% [88/319]) or patients (25% [58/233]) (P=.01 [legal professionals vs medical professionals]; P=.004 [legal professionals vs patients]).

Withdrawal of PM Therapy in the PM-Dependent Patient

Although more than a third of medical professionals (37% [124/331]) and patients (34% [77/227]) thought that a PM should not be turned off in a PM-dependent patient because doing so would be akin to physician-assisted death or euthanasia, fewer legal professionals were apt to believe the same way (15% [11/71]) (P<.001 [medical professionals vs legal professionals]; P=.003 [patients vs legal professionals]; eAppendix 2; case 3). In fact, most legal professionals did not think that turning off a PM in a PM-dependent patient constituted physician-assisted death or euthanasia (73% [52/71]). Significantly more legal professionals (81% [57/70]) thought the PM should be turned off in a PM-dependent patient because it was the patient's right to refuse continued therapy (P<.001 ([legal professionals vs medical professionals]; P=.006 [legal professionals vs patients]). More than half of the surveyed medical professionals (58% [190/328]) and patients (68% [157/230]) also agreed that the PM should be turned off. Most legal professionals tended to agree with turning off the PM. However, legal and medical professionals tended to consider that doing so was in the best interests of the patient less often than did surveyed patients (legal professionals: 8% [5/61]; medical professionals: 14% [45/319]; patients: 32% [74/228]; P<.001 [patients vs legal professionals]; P<.001 [patients vs medical professionals]).

Euthanasia in the Non–Device-Bearing Patient

Case 4 focused on a terminally ill patient whose PM-dependent and terminally ill twin brother died shortly after his PM therapy was withdrawn (at his own request). The patient summarily requested that he be given a drug to slow his heart rhythm artificially in the hopes that this would result in his dying in a fashion similar to that of his twin brother. Most medical professionals (99% [333/338]), legal professionals (86% [62/72]), and patients (91% [204/225]) thought that the physician should clearly explain that administering such a medication solely to cause death was not possible. Moreover, although most medical professionals (96% [322/334]) and patients (86% [191/222]) disagreed with the physician prescribing an oral medication that would result in a slow heart rhythm and eventually death, significantly fewer legal professionals held a similar opinion (68% [46/68]) (P<.001 [legal professionals vs medical professionals]; P=.001 [legal professionals vs patients]). In fact, significantly more legal professionals (25% [18/72]) than medical professionals (10% [34/331]) or patients (13% [30/226]) tended to agree that the patient's request was justifiable because of the clinical scenario (P=.002 [legal professionals vs medical professionals]; P=.03 [legal professionals vs patients]). In contrast, most medical professionals (93% [308/332]), legal professionals (92% [66/72]), and patients (86% [193/225]) disagreed with the patient's request being justifiable because of the twin brother's clinical scenario.

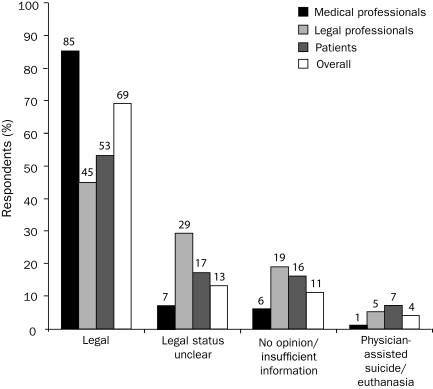

Comparison of Opinions on Withdrawal of PM Therapy

Almost a third of medical professionals thought that turning off a PM in a completely PM-dependent patient was akin to physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia (32% [110/339]). Despite this, most still thought that turning off a PM was either legal (41% [138/339]) or that the legal status was unclear (17% [58/339]) (Figure 2). Patients believed less often that turning off a PM was akin to physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia (24% [55/246]; P=.01) but believed similarly that turning off the device was legal (92/246; 40%; P=.44) or that the legal status was unclear (18% [44/246]; P=.83). Legal professionals, conversely, were more apt to perceive the legal status of turning off a PM as unclear (33% [24/73]) (P=.01 [legal professionals vs patients]; P=.003 [legal professionals vs medical professionals]). The plurality of legal professionals (37% [27/73]) thought that turning off a PM was legal and a minority (12% [9/73]) thought that turning off the PM was equivalent to physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia.

FIGURE 2.

Perceptions of the legality of withdrawing pacemaker (PM) therapy. Shown is the percentage of medical professionals, legal professionals, and patients who perceived withdrawal of PM therapy in a completely PM-dependent patient as legal, of unclear legal status, or as akin to physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia or who offered no opinion. More medical professionals perceived withdrawal of therapy as akin to physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia than legal professionals or patients (P<.001). In contrast, more legal professionals perceived the legal status as unclear than medical professionals or patients (P<.001). The percentage of respondents who perceived withdrawal as legal did not differ significantly among the groups. The actual percentage for each group is listed above the respective bar.

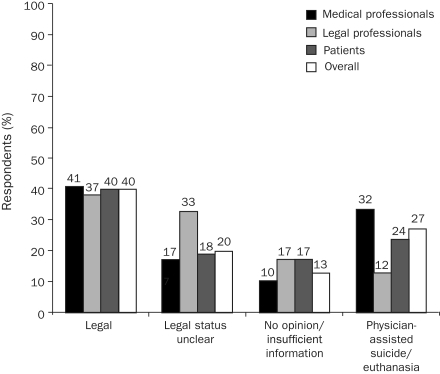

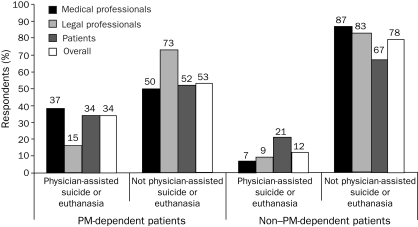

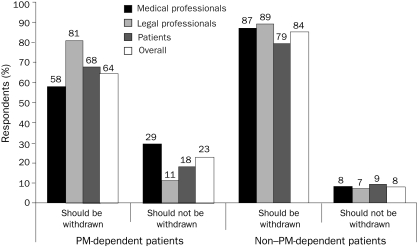

There were significant differences in perceptions of withdrawal of PM therapy between PM-dependent and non–PM-dependent patients. Although significantly more medical professionals (37% [124/331] vs 7% [22/334]; P<.001) and patients (34% [77/227] vs 21% [50/236]; P=.003) thought that withdrawing PM therapy was akin to physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia in a PM-dependent patient, there was no significant difference in the perception of legal professionals (15% [11/71] vs 9% [6/70]; P=.44) (Figure 3). Furthermore, there was no significant difference in legal professionals' attitudes regarding the appropriateness of withdrawal of PM therapy regardless of PM dependence (Figure 4). There were no significant differences in attitudes of medical professionals, legal professionals, and patients regarding withdrawal in the non-PM dependent patient. However, medical professionals were more likely to disagree with withdrawal of PM therapy in the PM-dependent patient than were legal professionals or patients (P=.002 [medical professionals vs legal professionals]; P=.002 [medical professionals vs patients]).

FIGURE 3.

Perceptions regarding pacemaker (PM) withdrawal at the end of life: akin to physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia? Shown is the percentage of medical professionals, legal professionals, and patients who perceived withdrawal of PM therapy as akin to physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia in a PM-dependent vs non–PM-dependent patient. Significantly more medical professionals and patients thought that PM withdrawal was akin to physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia when patients were PM-dependent than when they were not (P<.001). The actual percentage for each group is listed above the respective bar.

FIGURE 4.

Perceptions of whether pacemaker (PM) therapy should be withdrawn at the end of life on the basis of a patient's right to refuse. Shown is the percentage of medical professionals, legal professionals, and patients who thought that PM therapy should be withdrawn on the basis of the patient's right to refuse further therapy in a PM-dependent vs non–PM-dependent patient. Although most medical professionals, legal professionals, and patients thought that therapy should be withdrawn in either group, significantly fewer medical professionals and patients thought that PM withdrawal was appropriate when the patient was PM-dependent than when they were not (P<.001). However, the perception of legal professionals did not differ significantly with regard to device dependence. The actual percentage for each group is listed above the respective bar.

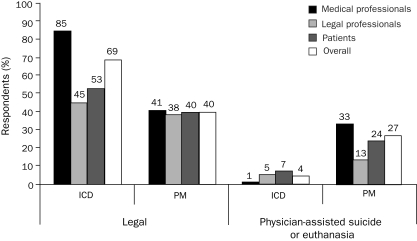

Comparison of Opinions on Withdrawal of ICD vs PM Therapy

Although overall more people thought that turning off an ICD was legal than turning off a PM in a PM-dependent patient, this was most marked among medical professionals and least among legal professionals (Figure 5). A similar number of legal professionals thought that turning off a device was legal regardless of whether it was an ICD or a PM (45% vs 38%; P=.50). Medical professionals were more likely to perceive turning off an ICD than a PM as legal (85% vs 41%; P<.001). Furthermore, medical professionals were the most likely to perceive turning off a PM as akin to euthanasia (33%) and significantly less likely to hold a similar belief about an ICD (1%; P<.001).

FIGURE 5.

Comparison of the perceptions of legality of turning off implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) vs pacemaker (PM) therapy. Shown is the percentage of medical professionals, legal professionals, and patients who perceived withdrawing ICD vs PM therapy (when the patient was PM-dependent) as either legal or as akin to physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia. Significantly more medical professionals and patients perceived withdrawal of ICD therapy as legal (P<.001); however, the opinions of legal professionals did not differ significantly on the basis of device type. However, all groups (medical professionals [P<.001], legal professionals [P<.01] and patients [P<.001]) were more likely to perceive withdrawing PM therapy as akin to physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia than withdrawing ICD therapy. The actual percentage for each group is listed above the respective bar.

DISCUSSION

With recent consensus guidelines regarding the withdrawal of implantable cardiac device therapy at the end of life, understanding the thinking of patients, legal professionals, and medical professionals regarding these issues remains key.16 Although several studies have focused on the attitudes of medical professionals regarding management of ICD therapy at the end of life, few have assessed attitudes regarding PMs, only 2 have looked at patient attitudes, and none have examined the attitudes of legal professionals.5-13,17,18 Understanding the attitudes of each group is important if we are to foster discussion between medical professionals and patients to ensure that all parties are equally satisfied and comfortable with the decisions made.

The withdrawal of ICD therapy at the end of life has become much more acceptable among medical professionals and is generally thought to be ethically permissible.5-8,19,20 However, the legality of this is not as clear, in part due to the lack of court cases focusing specifically on withdrawal of implantable cardiac device therapy. Furthermore, most legal cases have focused on withdrawal of life-sustaining therapies that are often more proximate to the end-of-life event (eg, intubation and mechanical ventilation, feeding tubes, and intravenous hydration) or visibly invasive (eg, hemodialysis). Cardiac device therapies, such as ICDs and PMs, are unique in that they dwell within the patient's body and, except in the case of an ICD shock, are often imperceptible to the patient.

The survey responses indicate a wide range of perceptions regarding the withdrawal of device therapy depending on the case (ie, which type of device is being considered) and the background of the respondent (ie, whether a patient, a legal professional, or a medical professional). Legal professionals were the most likely to think that device withdrawal was either legal or that the legal status was unclear, regardless of the type of device. It is interesting to note, however, that the opinions of medical professionals were the most wide-ranging, with a large majority perceiving the withdrawal of ICD therapy as legal and nearly a third perceiving the withdrawal of PM therapy in the PM-dependent patient as akin to physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia.

To understand the unique differences between withdrawal of a life-sustaining therapy and physician-assisted suicide, a distinction in terms is necessary. In physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia, the patient's life is terminated using a prescribed method by a clinician and self-administered by the patient or directly administered by the clinician.2,3,21-23 In withdrawing an unwanted therapy, the intent is not to hasten death but to withdraw a therapy that is perceived as a burden.22,24,25 In the context of ethical principles, regardless of the fact that a PM in a PM-dependent patient is a constitutive therapy without the continued operation of which the patient may not survive, it still represents an artificial life-sustaining treatment that the patient has the right to refuse at any time. Furthermore, established case law holds that patients have the right to refuse or request the withdrawal of any treatment and has repeatedly held that no single treatment holds unique moral status, although no single case has focused specifically on management of ICDs and PMs at the end of life. Thus, the management of ICDs and PMs still falls in line with prior legal cases regarding withdrawal of specific life-sustaining therapies.16

One contention that can be made is that the patient who is PM-dependent may wish for withdrawal of PM therapy for the primary purpose of hastening death. However, a PM also constitutes continuance of an artificial therapy that requires continued follow-up and can be associated with a variety of complications related to both sensing and provision of therapy. Thus, continued operation of a PM carries with it necessary continued follow-up that a patient may regard as burdensome. Furthermore, withdrawal of a PM, even if it may hasten the time of death, is not the same as providing a medication that would cause death in a similar fashion (ie, by slowing the heart rate to a degree that would cause death).

Although most respondents thought that PM therapy should be withdrawn in the PM-dependent patient, most also thought that acceding to the wish of the twin brother who requested that his own heart rate be slowed via the introduction of a therapy such as a pharmaceutical agent was not appropriate. Moreover, although some respondents agreed that the twin brother's request was justifiable on the basis of his clinical scenario, the overwhelming majority of respondents did not believe that the request was justifiable because the PM-dependent brother may have died faster as a result of the withdrawal of a life-sustaining therapy. It is interesting to note that significantly more legal professionals than medical professionals or patients (who tended to have similar responses) were likely to think that the patient's request was justifiable because of the clinical scenario (25%) or to agree with prescribing a medication that would lead to death (18%). However, legal professionals, medical professionals, and patients were all similar in their assessment that the reason for the request being justifiable had nothing to do with the ability of the twin brother to turn off his PM and perhaps die faster as a result of an inadequate heart rate or rhythm. This is consistent with prior decisions by the US Supreme Court in that the decision is not one of a “right to die” but rather of a “right to refuse unwanted treatments,” as in the Cruzan decision,2 and in that withholding or withdrawing treatments is not equivalent to physician-assisted death, as in the Vacco decision.21

Most respondents thought that all device therapy, whether an ICD, a PM in a non–PM-dependent patient, or a PM in a PM-dependent patient, should be withdrawn when it reflects the patient's wishes. This is despite the fact that few respondents thought that withdrawing any of these therapies was in the best interests of the patient. Respondents perceived a difference between ICDs and PMs in terms of the appropriateness of withdrawal, especially when taking into account PM dependence. These differences in perception were most marked among medical professionals and least among legal professionals, perhaps reflecting a difference in how life-sustaining therapies are perceived by medical vs legal professionals. Legal professionals tend to perceive all artificial life-sustaining therapies as equal regardless of temporal distinctions between the time of withdrawal and the time of death. Specifically, although withdrawal of ICD therapy in a patient with no episodes of ventricular tachyarrhythmia may not have any association with the time of death, withdrawal of a PM in an entirely PM-dependent patient may have a closer temporal relationship. The fact that the pacemaker still represents an artificial therapy, regardless of how constitutive, and that it is continuous does not alter the fact that it is an artificial therapy that a patient can refuse or request the withdrawal of, just as a patient can refuse or request the withdrawal of mechanical ventilation.

However, the medical professional will be the one involved in the withdrawal of any device therapy. Thus, the personal principles of the medical professional involved in the patient's care should be taken into account when the decision to withdraw therapy is made. Although most respondents agreed that device therapy should be withdrawn, more than one-third of medical professionals still perceive withdrawing PM therapy as akin to physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia. Although medical professionals are not compelled to carry out device deactivation in these cases, they should also inform the patient of their preference and not impose these beliefs on the patient.26-29 Most medical professionals and patients thought that it would be inappropriate to involve a different clinician who might be willing to provide the desired care; however, it is generally accepted that such an act is permissible when the primary clinician thinks that performing an act that is legally and/or ethically allowable goes against his or her personal beliefs.

Our study has the limitations typical of survey-based studies. First, only 12% of those surveyed responded. Thus, there may be some bias reflected among those who chose to respond. The differences in opinion among medical professionals, legal professionals, and patients may also reflect differences in the understanding of how these devices function. The attitudes of patients with devices may also reflect the attitudes of the medical professionals who care for them because their understanding of devices is often largely dependent on counseling by their clinicians. Furthermore, medical and legal professional respondents may represent a geographically heterogeneous population that may be affected by local differences in state law. Moreover, given that all patients were seen in a single institution, their responses may not be readily applicable to patients seen in other areas of the country.

In particular, only 8% of medical professionals responded to the survey, raising the question of whether these results can be generalized to all medical professionals. First, it was unclear in which geographic regions the respondents resided, and thus it is not necessarily clear if the respondents represented a geographically diverse population. Second, the respondents may have represented those with strong opinions related to end-of-life care and thus may not reflect the opinions of the average medical professional. However, our findings parallel those noted in recent Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statements.16 Thus, the opinions of the respondents in our cohort at least appear to parallel those reached by expert consensus regarding the same issues.

Similarly, the legal professionals surveyed represented faculty from only 5 select law schools. Although these law schools represented a wide-ranging geography, the 17% response rate suggests the possibility that respondents may not have been equally distributed among all law schools. Furthermore, similar to medical professionals, the legal professionals who chose to respond may have already had strong opinions on the subject. Responses from legal professionals may also have been influenced by their specific area of legal interest (eg, constitutional law, malpractice law). Thus, it is unclear if the sum of their individual opinions may be extrapolated to a more general legal opinion. However, the lack of existing case law in this area means that, until such a case appears before a court, interpretations must be based on prior judicial decisions related to end-of-life care.

CONCLUSION

Although most medical professionals, legal professionals, and patients think that implantable cardiac device therapy should be withdrawn on the basis of the patient's right to refuse continued life-sustaining therapy, clear differences remain in how ICDs and PMs are perceived, especially when the patient is PM-dependent. These differences are most apparent among medical professionals, with almost one-third of medical professionals perceiving withdrawal of a PM as physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia and only 1% believing the same about an ICD. Legal professionals, however, tended to see few differences between withdrawal of ICDs and PMs, perhaps reflecting a different vantage point on the withdrawal of life-sustaining therapies. In fact, legal professionals most commonly thought that there was a lack of clarity in whether turning off an ICD or PM was legal. Patients, in turn, have a wide range of opinions regarding the appropriateness and legality of withdrawing therapies. Although existing case law does not specifically focus on ICDs or PMs, extension of case law to these therapies generally supports their withdrawal when the patient requests it. Despite this, perceptions about how these devices should be managed at the end of life remain widely varied. The importance of recognizing differing perceptions of withdrawal of device therapy and of providing continued education regarding end-of-life care is highlighted in our study by the fact that greater than one-third of respondents overall thought that withdrawing PM therapy in the PM-dependent patient was akin to physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia. Thus, these results highlight the importance of communication among medical professionals to identify distinctions between withdrawing ICDs and PMs and between patients and clinicians to clarify patient perceptions regarding device management and goals of care at the end of life.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Heart Rhythm Society for its distribution of the online survey to its membership.

Footnotes

Survey development and statistical analysis were supported in part by a grant from the Mayo Clinic Program in Professionalism and Ethics.

An earlier version of this article appeared Online First.

Supporting Online Material

www.mayoclinicproceedings.com/content/85/11/981/suppl/DC1

eAppendix 1

eAppendix 2

REFERENCES

- 1.In re Quinlan, 70 NJ 10, 355 A.2d 647 (1976). New Jersey Supreme Court. Health Law and Bioethics: Cases in Context Web site. http://aspen.skeeydev.net/books/johnsonkrause/INREQUINLANSupremeCourtofNewJersey.doc Accessed August 24, 2010

- 2.Cruzan by Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Dept of Health, 497 US 261. 88-1503 (1990). Supreme Court of the United States. Cornell Legal Information Institute Web site. http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/historics/USSC_CR_0497_0261_ZS.html Accessed August 24, 2010

- 3.Annas GJ. “Culture of life” politics at the bedside—the case of Terri Schiavo. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1710-1715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Annas GJ. The Rights of Patients: The Authoritative ACLU Guide to the Rights of Patients. 3rd ed.Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein NE, Lampert R, Bradley E, Lynn J, Krumholz HM. Management of implantable cardioverter defibrillators in end-of-life care. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:835-838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger JT. The ethics of deactivating implanted cardioverter defibrillators. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:631-634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis WR, Luebke DL, Johnson NJ, Harrington MD, Constantini O, Aulisio MP. Withdrawing implantable defibrillator shock therapy in terminally ill patients. Am J Med. 2006;119:892-896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mueller PS, Hook CC, Hayes DL. Ethical analysis of withdrawal of pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator support at the end of life. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:959-963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mueller PS, Jenkins SM, Bramstedt KA, Hayes DL. Deactivating implanted cardiac devices in terminally patients: practices and attitudes. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2008;31:560-568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldstein N, Bradley E, Zeidman J, Mehta D, Morrison RS. Barriers to conversations about deactivation of implantable defibrillators in seriously ill patients: results of a nationwide survey comparing cardiology specialists to primary care physicians [letter]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(4):371-373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quill TE, Barold SS, Sussman BL. Discontinuing an implantable cardioverter defibrillator as a life-sustaining treatment. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74:205-207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiegand DL, Kalowes PG. Withdrawal of cardiac medications and devices. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2007;18:415-425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sherazi S, Daubert JP, Block RC, et al. Physicians' preferences and attitudes about end-of-life care in patients with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:1139-1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zellner RA, Aulisio MP, Lewis WR. Should implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and permanent pacemakers in patients with terminal illness be deactivated? Deactivating permanent pacemaker in patients with terminal illness. Patient autonomy is paramount. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2(3):340-344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kay GN, Bittner GT. Should implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and permanent pacemakers in patients with terminal illness be deactivated? Deactivating implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and permanent pacemakers in patients with terminal illness. An ethical distinction. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2(3):336-339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lampert R, Hayes DL, Annas GJ, et al. HRS expert consensus statement on the management of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIED) in patients nearing end of life or requesting withdrawal of therapy. Heart Rhythm Online. http://www.hrsonline.org/Policy/ClinicalGuidelines/upload/ceids_mgmt_eol.pdf Accessed August 24, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Goldstein NE, Mehta D, Siddiqui S, et al. “That's like an act of suicide” patients' attitudes toward deactivation of implantable defibrillators. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(suppl 1):7-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berger JT, Gorski M, Cohen T. Advance health planning and treatment preferences among recipients of implantable cardioverter defibrillators: an exploratory study. J Clin Ethics. 2006;17:72-78 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silveira MJ. When is deactivation of artificial pacing and AICD illegal, immoral and unethical? Am J Geriatr Cardiol. 2003;12:275-276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braun TC, Hagen NA, Hatfield RE, Wyse DG. Cardiac pacemakers and implantable defibrillators in terminal care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;18:126-131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vacco, Attorney General of New York et al. v Quill et al. 521 US 793. 95-1858 (1997). Supreme Court of the United States. Cornell Legal Information Institute Web site. http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/95-1858.ZS.html Accessed August 24, 2010

- 22.Meisel A, Snyder L, Quill T. Seven legal barriers to end-of-life care: myths, realities, and grains of truth. JAMA. 2000;284:2495-2501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrison RS, Meier DE. Palliative care. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(25):2582-2590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snyder L, Leffler C, Ethics and Human Rights Committee. American College of Physicians Ethics manual: fifth edition. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(7):560-582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhymes JA, McCullough LB, Luchi RJ, Teasdale TA, Wilson N. Withdrawing very low-burden interventions in chronically ill patients. JAMA. 2000;283:1061-1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs (cor) Code of Medical Ethics: Current Opinions and Annotations 2008-2009. AMA Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. Chicago, IL: AMA Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Medical Association Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs Physician Objection to Treatment and Individual Patient Discrimination: CEJA Report 6-A-07. Chicago, IL: AMA Press; 2007:1-4 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katz J. The Silent World of Doctor and Patient. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emanuel EJ, Emanuel LL. Four models of the physician-patient relationship. JAMA. 1992;267:2221-2226 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.