Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To identify patient expectations regarding chaplain visitation, characteristics of patients who want to be visited by a chaplain, and what patients deem important when a chaplain visits.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS: Three weeks after discharge, 4500 eligible medical and surgical patients from hospitals in Minnesota, Arizona, and Florida were surveyed by mail to collect demographic information and expectations regarding chaplain visitation. The survey was conducted during the following time periods: Minnesota participants, April 6 until April 25, 2006; Arizona participants, October 16, 2008, until January 13, 2009; Florida participants, October 16, 2008, until January 20, 2009. Categorical variables were summarized with frequencies or percentages. Associations between responses and site were examined using χ2 tests. Multivariate logistic regression was used to assess the likelihood of wanting chaplain visitation on the basis of patient demographics and perceived importance of reasons for chaplain visitation.

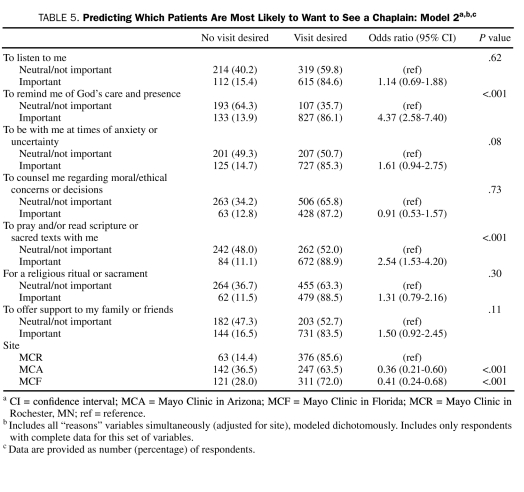

RESULTS: About one-third of those surveyed responded from each site. Most were male, married, aged 56 years or older, and Protestant or Catholic. Of the respondents, nearly 70% reported wanting chaplain visitation, 43% were visited, and 81% indicated that visitation was important. The strongest predictor of wanting chaplain visitation was denomination vs no indicated religious affiliation (Catholic: odds ratio [OR], 8.11; 95% confidence interval [CI], 4.49-14.64; P<.001; evangelical Protestant: OR, 4.95; 95% CI, 2.74-8.91; P<.001; mainline Protestant: OR, 4.34; 95% CI, 2.58-7.29; P<.001). Being female was a weak predictor (OR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.05-2.09; P=.03), as was site. Among the reasons given by respondents for wanting chaplain visitation, the most important were that chaplains served as reminders of God's care and presence (OR, 4.37; 95% CI, 2.58-7.40; P<.001) and that they provided prayer or scripture reading (OR, 2.54; 95% CI, 1.53-4.20; P<.001).

CONCLUSION: The results of this study suggest the importance medical and surgical patients place on being visited by a chaplain while they are hospitalized. Those who valued chaplains because they reminded them of God's care and presence and/or because they prayed or read scripture with them were more likely to desire a visit. Our results also suggest that being religiously affiliated is a very strong predictor of wanting chaplain visitation.

Patients who valued chaplains because they reminded them of God's care and presence and/or because they prayed or read scripture with them were more likely to request chaplain visitation.

CI = confidence interval; MCA = Mayo Clinic in Arizona; MCF = Mayo Clinic in Florida; MCR = Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN; OR = odds ratio

Studies indicate that many people rely on spirituality to help them cope with the stress of medical crises,1 surgical procedures,2 chronic medical illnesses,3,4 psychiatric disorders,5,6 and the end of life.7 Spirituality has also been linked to health outcomes,8-10 patient quality of life,11,12 and patient satisfaction.3 These studies illustrate the importance of responding to the spiritual needs of patients to provide optimal care for them.

Certified hospital chaplains are theologically and clinically trained health care professionals whose work involves understanding the spirituality of patients and providing spiritual care appropriate to patients' expectations and needs. Their ministry complements the work of other health care professionals and is valued by patients.10 Although hospitals strive to provide comprehensive support for patients, including spiritual care, this is a financially challenging time for health care institutions. Expenditures are being carefully monitored, and services are being scrutinized. Especially in this climate, it is imperative that chaplains continue to pursue ways to practice good stewardship of the resources entrusted to them while providing important spiritual care and support to those who need it.

The aims of this multisite patient-expectation survey were to identify (1) patient expectations regarding chaplain visitation, (2) characteristics of patients who want to be visited by a chaplain, and (3) what patients deem important when a chaplain visits and how that relates to whether they want to be visited.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

Eligible patients were aged 18 years or older and had been hospitalized in medical, surgical, rehabilitation, or intensive care units for more than 24 hours at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN (MCR); Mayo Clinic in Arizona (MCA); or Mayo Clinic in Florida (MCF). Obstetric patients, psychiatric patients, outpatients, and persons who indicated that they were not able to complete all aspects of the study were excluded. Mailings were not sent to families of patients who were known to have died during hospitalization or after discharge.

The study protocol was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board in August 2008. Informed consent was not required.

Setting

The Mayo Clinic hospitals provide inpatient care to support Mayo Clinic's medical and surgical specialties. Most of the patients they serve come from the surrounding areas (MCR, 66%; MCA, 78%; MCF, 80%), and others come from more distant national and international areas. Saint Marys Hospital and Rochester Methodist Hospital in Rochester, MN, form a large tertiary care hospital system with strong religious roots. Saint Marys Hospital was founded in 1889 by a Catholic order of religious women, the Rochester Franciscans, in partnership with Dr William Worrall Mayo. Rochester Methodist Hospital was built in 1966 with partial funding from the Methodist Church. Saint Marys Hospital and Rochester Methodist Hospital entered into formal association with Mayo Clinic in 1986, forming an integrated medical center. They have a combined licensed bed capacity of 1991. Mayo Clinic hospitals in Phoenix, AZ, and Jacksonville, FL, were planned, designed, and built by Mayo Clinic and have no formal religious affiliation. Mayo Clinic Hospital in Phoenix, AZ, was completed in the fall of 1998. Mayo Clinic Hospital in Jacksonville, FL, opened in the spring of 2008. These hospitals, which are smaller than Saint Marys Hospital and Rochester Methodist Hospital, have more than 200 licensed beds each (MCA, 244; MCF, 214).

Certified hospital chaplains are employed at each site, but the number of chaplains available to serve inpatients differs by site. At the time of the survey, chaplain staffing allowed for a chaplain to patient ratio of about 2:100 at MCR, 1:100 at MCA, and 1.5:100 at MCF.

Survey Instrument

The survey instrument was designed by the investigators in consultation with staff chaplains and the Multidisciplinary Research Committee of the Mayo Clinic Department of Chaplain Services. Included were questions related to (1) demographics, (2) duration and area of hospitalization, (3) awareness of the availability of chaplains, and (4) expectations of chaplain visit initiation, follow-up, and frequency.

Participants were also asked whether they were visited by a hospital chaplain and/or contacted by a representative of their church, synagogue, or mosque. (The word contact in the latter case was intended to offer an option for patients to report any communication with these religious representatives, not only visitation.) If they received a visit from a chaplain or a contact from a representative of their religious group, they were asked to rate the visit or contact in terms of importance on a 5-point Likert-like scale with the following response options: very important, somewhat important, neither important nor unimportant, somewhat unimportant, or very unimportant.

Participants were also asked to indicate reasons for wanting to see a chaplain from among the following response options: to listen to me, to remind me of God's care and presence, to be with me at times of particular anxiety or uncertainty, to counsel me regarding moral/ethical concerns or decisions, to pray and/or read scripture or sacred texts with me, to provide a religious ritual or sacrament, or to offer support to my family or friends. These response options were based on the clinical experience of chaplains and previous research suggesting that hospital ministry involves both religious and more generically supportive dimensions.13-15 Patients were asked to rate each item in terms of importance to them on a 5-point Likert-like scale, using the same response options as described in the preceding paragraph. At the end of the survey form, participants were encouraged to write additional comments or suggestions related to their hospitalizations.

Data Collection

The survey, a letter inviting participation, and a stamped, preaddressed return envelope were prepared by the Mayo Clinic Survey Research Center. The survey packet was mailed to 1500 consecutive eligible persons from each of the 3 sites within 3 weeks of their discharge from the hospital. Participants from MCR were surveyed from April 6 until April 25, 2006. Participants from MCA were surveyed from October 16, 2008, until January 13, 2009. Participants from MCF were surveyed from October 16, 2008, until January 20, 2009. (The duration of the survey was longer in the latter 2 sites because of the lower inpatient census.) No attempt was made for follow-up collection. Surveys that were returned within 1 month of the mailing were included in the analysis.

Statistical Analyses

Specific identifying information was removed from the data collected, and results were reported in aggregate. Measured characteristics were summarized with frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and with median and interquartile range for length of stay. On the basis of their reported religious preference, participants were placed in 1 of 5 groups: Catholic, mainline Protestant, evangelical Protestant, Jewish, or Other. (The category “Other” included participants endorsing religious groups with varied perspectives, but these groups were too small to be analyzed independently.) Participants who indicated “no religious affiliation” were grouped with those who left the question blank, forming a sixth group for the analysis.

The association between the categorical responses to survey items and the geographic site (MCR, MCA, MCF) was studied using χ2 tests. For the survey items with Likert-like response options (5-level importance scale), χ2 tests were performed on noncollapsed categories; however, a collapsed version of the data is presented in the Tables. Length of stay was compared between sites using the Kruskal-Wallis test. The survey question asking how often the patient would have liked to be visited by a chaplain was dichotomized as “wanting at least one visit” vs all other or missing responses. (After its use at MCR, we added the response option “not at all” to the question “How often would you have liked to be visited?”) In the dichotomized outcome for desired visits, the number of missing responses was included in the denominator, assuming that those who skipped the question did not want a visit (particularly true for MCR). The likelihood of wanting a chaplain visit was then compared between the survey responses with multivariate logistic regression. This model included the set of patient characteristics that are presumably known on hospital admission (expected length of stay, whether the hospitalization was expected, reason for the hospitalization, age, sex, religious affiliation, and marital status). A second multivariate logistic regression model included the set of survey items related to the reasons patients reported as important (or not) when a chaplain visits. A dichotomized version of “importance” (very/somewhat important vs neutral/somewhat/very unimportant) was used in the modeling procedure. Given some differences found between sites, all logistic regression models were adjusted for site by including it among the covariates. Odds ratios (ORs) (adjusted for site as well as all other covariates included in the model) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported. P<.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

The number of missing responses varied from question to question. If the question was not answered, no imputation was used, and the response was left as missing (not included in the denominator) unless otherwise noted. The total number of observations used in the analyses for each survey item is noted in the Tables. Because the surveys were returned anonymously, it was not possible to determine the characteristics of those who did not respond or adjust for baseline differences in the analysis.

RESULTS

Demographics

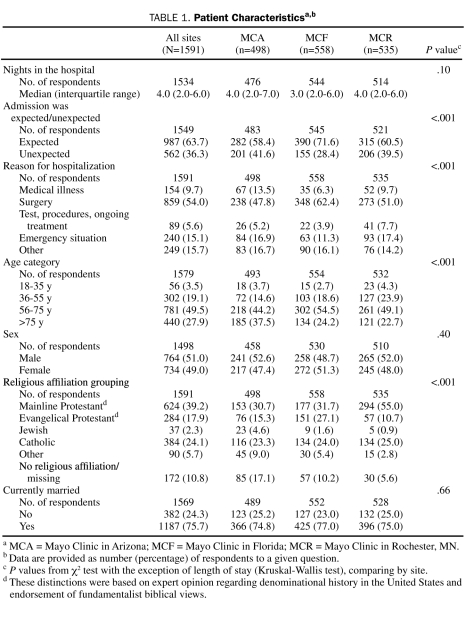

Of the 4500 recipients of the mailed survey, about one-third from each site responded (MCA, n=498; MCF, n=558; MCR, n=535). The overall response rate was 35% (1591/4500; percentages are figured on a denominator of 1591, unless otherwise indicated). Most respondents were married (1187/1569; 75.7%), were aged 56 years or older (1221/1579; 77.3%), and reported an affiliation with a Catholic or Protestant denomination (1292; 81.2%). About one-half were men (764/1498; 51.0%). The median length of hospital stay of participants was 4 nights (interquartile range, 2-6 nights). Most respondents indicated that their hospitalization was expected (987/1549; 63.7%), with over half being hospitalized for a surgical procedure (859; 54.0%). Significant differences by site were found for many of these characteristics (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristicsa,b

Visitation by Hospital Chaplains

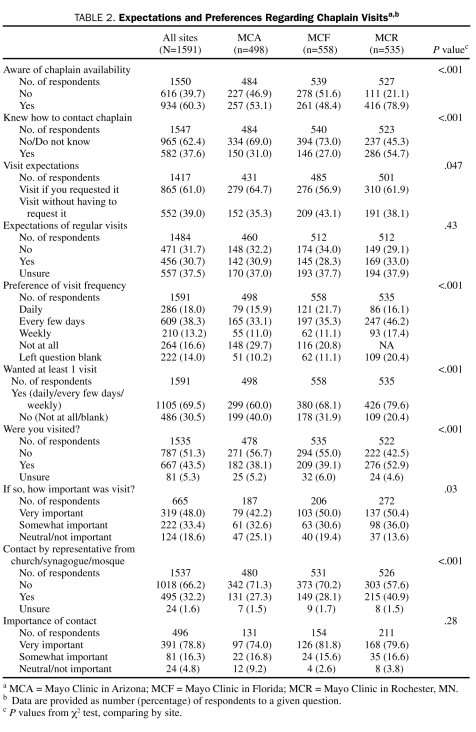

Nearly 70% (1105) of respondents reported wanting to be visited by a chaplain during their hospitalization, but only 43.5% (667/1535) reported being visited. Almost a third (30.7%; 456/1484) expected regular follow-up visits from a chaplain, and nearly 4 of 10 patients (39.0%; 552/1417) expected a chaplain to visit them without their making a request. Almost one-third (30.5%; 486) either reported that they did not want to see a chaplain or left the item blank. Although 60.3% (934/1550) of the respondents were aware that chaplains were available to them, only 37.6% (582/1547) knew how to contact a chaplain. Of those participants who were visited by a hospital chaplain, 81.4% (541/665) indicated that this visit was important to them. Responses to these items differed significantly between sites (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Expectations and Preferences Regarding Chaplain Visitsa,b

Contact by Representatives From Church, Synagogue, or Mosque

Patients were also asked whether they had been contacted by a representative of their church, synagogue, or mosque. At MCR, 40.9% (215/526) of participants had received such a contact, which was significantly more than at MCA (27.3%; 131/480) or MCF (28.1%; 149/531). The vast majority of patients who had been contacted by a denominational representative rated the contact as very important (78.8%; 391/496), with no significant difference found between sites (Table 2). Significantly more of those who were contacted by their own church representative than those who were not contacted reported a preference for wanting to be visited by a chaplain (81.4% vs 66.6%; P<.001; Fisher exact test; data not shown).

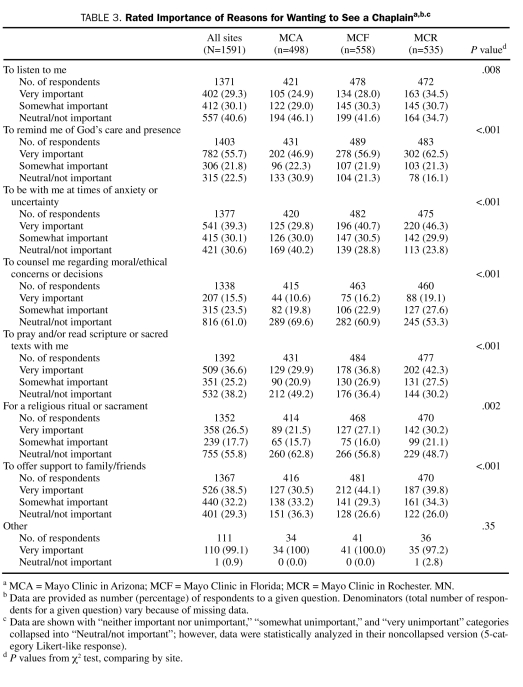

Reasons for Wanting to See a Chaplain

The reason most highly endorsed by participants for wanting to see a chaplain was to be reminded of God's care and presence. More than 77% endorsed this as an important reason to see a chaplain (55.7%, very important; 21.8%, somewhat important). Other reasons endorsed by more than half of the participants as very important or somewhat important were to provide support for their family and friends (70.7%), to be with them during times of anxiety (69.4%), and to pray or read scripture with them (61.8%). There were significant differences on all items between the sites (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Rated Importance of Reasons for Wanting to See a Chaplaina,b.c

Predicting Which Patients Are Most Likely to Want to See a Chaplain

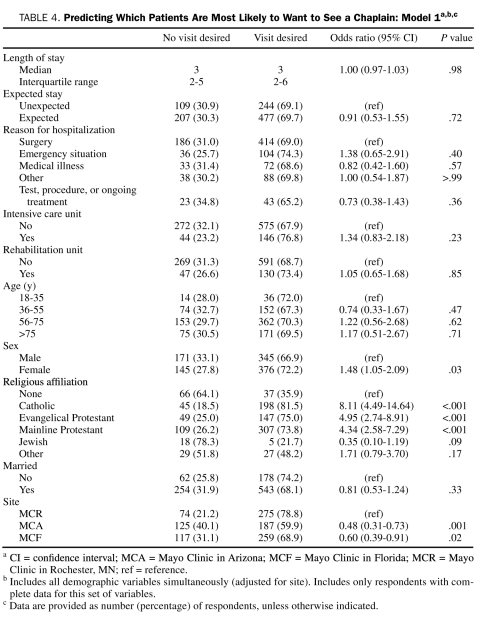

Patients who identified themselves as being affiliated with a specific religious denomination were much more likely to want to be visited by a hospital chaplain than were those who did not report a religious affiliation. From the first multivariate logistic regression model, which included all patient and hospitalization characteristics simultaneously (as well as site), we found that, as compared with those with no indicated religious affiliation, the odds for wanting to be visited were nearly 8 times higher for Catholics (OR, 8.11; 95% CI, 4.49-14.64; P<.001), almost 5 times higher for evangelical Protestants (OR, 4.95; 95% CI, 2.74-8.91; P<.001), and more than 4 times higher for mainline Protestants (OR, 4.34; 95% CI, 2.58-7.29; P<.001). Women also were more likely than men to want a visit from a hospital chaplain (OR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.05-2.09; P=.03). Length of stay, reason for hospitalization, time in the intensive care or rehabilitation unit, age, and marital status were not predictive of wanting to be visited by a chaplain (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Predicting Which Patients Are Most Likely to Want to See a Chaplain: Model 1a,b,c

Important Reasons for a Chaplain to Visit

From the second multivariate logistic regression model, which included the set of “importance” ratings for reasons to see a chaplain, we found that the odds of wanting to be visited were more than 4 times higher for those who endorsed the importance of chaplains as reminders of God's care and presence, as compared with those who did not endorse this as important (OR, 4.37; 95% CI, 2.58-7.40; P<.001). Also predictive was reporting the importance of the chaplain's visit for prayer or scripture reading (OR, 2.54; 95% CI, 1.53-4.20; P<.001) (Table 5). Results were all adjusted for the significant differences found between sites.

TABLE 5.

Predicting Which Patients Are Most Likely to Want to See a Chaplain: Model 2a,b,c

DISCUSSION

The current climate of budget vigilance and cost containment within health care institutions has created a great challenge for hospital chaplains who must find ways to provide spiritual support to hospitalized patients with more limited resources. The results of the current study provide insights that may be helpful to health care administrators, hospital chaplains, physicians, nurses, and others involved in the clinical aspects of health care as they consider allocation of staff and other resources. First, the results showed that most hospitalized patients in the 3 diverse geographic regions studied wanted to be visited by a chaplain. Second, an affiliation with a Catholic or Protestant denomination was the strongest predictor of wanting a chaplain to visit. Third, participants who wanted to be visited were most likely to value a chaplain as a reminder of God's caring presence and as one who prays or reads scripture with them.

It is important for chaplains to know and appreciate the importance that patients place on being visited by them. Our results indicated that many more patients wanted a visit than received one, which mandates an exploration of ways to meet this patient expectation. One concern is whether the existing number of chaplains on staff is sufficient to provide spiritual care to all those who would like it, and if not, how this might be addressed. A place to begin would be to determine strategies to increase the visibility of chaplains and to provide patients with clear directions about how to request pastoral care, especially in light of the finding that more than a third expected to be visited without making a request and more than half did not know how to contact a chaplain.

It is helpful to know that Catholics and Protestants are most likely to want to be visited by a chaplain. Unfortunately, information about patients' denomination is not always available and at times is inaccurate. For example, in the Mayo Clinic hospitals in Rochester, MN, as many as 27% of patients may be listed as “religious preference unknown” on a given day. Our results suggest the importance of making efforts to update this information so that patients' expectations can be met.

The only “reasons” variables that were predictive of patients' wanting a chaplain to visit were the importance of a chaplain as a reminder of God's caring presence and as one who prays or reads scripture with them. These findings affirm the unique role that a chaplain serves for patients as a connection to the sacred. It is also important to note that other supportive functions of a chaplain were highly endorsed by the respondents. Thus, it seems that for chaplains to truly meet the expectation of patients, they must first learn about an individual's spiritual concerns and respond to each patient with these in mind.

A patient's sex is a weak predictor of a greater desire to see a chaplain while hospitalized. Women are 1.5 times more likely than men to report wanting to be visited by a chaplain. However, more than two-thirds of male patients reported wanting to be visited, and therefore this finding does not seem to be clinically relevant.

Surprisingly, factors such as length of stay, reason for hospitalization, marital status, and age were not predictive of wanting a visit. This is important to keep in mind as chaplains prioritize their visits. Also surprising was the finding that being contacted by a representative from one's congregation did not preclude wanting to be seen by a hospital chaplain. In fact, those who received such contacts were significantly more likely to want to be visited by a hospital chaplain than were those who had not been contacted. Because it is probable that some of those surveyed came from beyond a 120-mile radius, it is possible that some of those who were contacted by their congregation received phone calls or cards and wanted a face-to-face visit from a hospital chaplain as well. It may also be that those who were contacted by their congregation were more religiously interested and involved and that they appreciated consistent spiritual care while in the hospital.

One of the strengths of this survey research project is its large sample drawn from 3 different parts of the United States. Another is that participants were hospitalized in either a large hospital system with religious roots or 1 of 2 smaller hospitals with secular history. The ratio of chaplains available to inpatients at each site also varied, ranging from 1 to 2 per 100. These differences increase the generalizability of our findings. The statistical differences found between the 3 sites merit further investigation.

Our study is limited in that it does not address the entire scope of the clinical practice of hospital chaplains. We did not survey obstetric, gynecologic, or psychiatric inpatients, nor did we address our growing clinical ministry with outpatients. The study also has limited information on patients who report other than a Catholic or Protestant religious affiliation and those who are younger than 35 years. Gathering information about these groups is very important. A study exploring the relationship between the spiritual care given and patient well-being and satisfaction would also be of value.

CONCLUSION

Hospital chaplains provide a unique and valued role in the care of patients. This study provides data suggesting the importance medical and surgical patients place on being visited by a chaplain while they are hospitalized. Those who valued chaplains because they reminded them of God's care and presence and/or prayed or read scripture with them were more likely to desire a visit. Our results also suggest that being religiously affiliated is a very strong predictor of wanting chaplain visitation. These findings can guide institutions in responding to patients' expectations and implementing best practices in providing spiritual care for their patients.

However, the results must be used cautiously. Chaplains are trained to respect and care for their patients as individuals who are not defined by their reported religious preference, sex, or any other variable. Although our predictive data may be helpful in triaging care when time is very limited, it cannot be used to overshadow the vital importance of honoring the uniqueness of each person and assessing and responding to each patient one by one.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Financial support included a grant from the Saint Marys Hospital Sponsorship Board and discretionary funds from the Department of Chaplain Services.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbott KH, Sago JG, Breen CM, Abernethy AP, Tulsky JA. Families looking back: one year after discussion of withdrawal or withholding of life-sustaining support. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(1):197-201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarpley JL, Tarpley MJ. Spirituality in surgical practice. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;194(5):642-647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.King DP, Platz E. Addressing the spiritual concerns of patients in the non-intensive care setting. South Med J. 2003;96(3):321-322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koenig HG, Paragment KI, Nielsen J. Religious coping and health status in medically ill hospitalized older adults. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998;186(9):513-521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corrigan P, McCorkle B, Schell B, Kidder K. Religion and spirituality in the lives of people with serious mental illness. Community Ment Health J. 2003;39(6):487-499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tepper L, Rogers SA, Coleman EM, Malony HN. The prevalence of religious coping among persons with persistent mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(5):660-665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hinshaw DB. Spiritual issues in surgical palliative care. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85(2):257-272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mueller P, Plevak D, Rummans T. Religious involvement, spirituality and medicine: implications for clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(12):1225-1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Tarakeshwar N, Hahn J. Religious coping methods as predictors of psychological, physical and spiritual outcomes among medically ill elderly patients: a two-year longitudinal study. J Health Psychol. 2004;9(6):713-730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piderman KM, Marek DV, Jenkins SM, Johnson ME, Buryska JF, Mueller PS. Patients' expectations of hospital chaplains. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(1):58-65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rummans TA, Clark MM, Sloan JA, et al. Impacting quality of life for patients with advanced cancer with a structured multidisciplinary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(6):635-642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson ME, Piderman KM, Sloan JA, et al. Measuring quality of life in patients with cancer. J Support Oncol. 2007;5(9):437-442 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Catholic Health Initiatives Measures of a Chaplain: Performance and Productivity: Denver, CO: Catholic Health Initiatives Task Force; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibbons JL, Thomas J, VandeCreek L, Jessen AK. The value of hospital chaplains: patient perspectives. J Pastoral Care. 1991;45(2):117-125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.VandeCreek L, Lyon MA. Ministry of hospital chaplains: patient satisfaction. J Health Care Chaplain. 1997;6(2):1-61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.